In July 1979, the Jubilee Gardens on the south bank of the River Thames near Waterloo Station and County Hall, was the location for the World’s Longest Safety Poster:

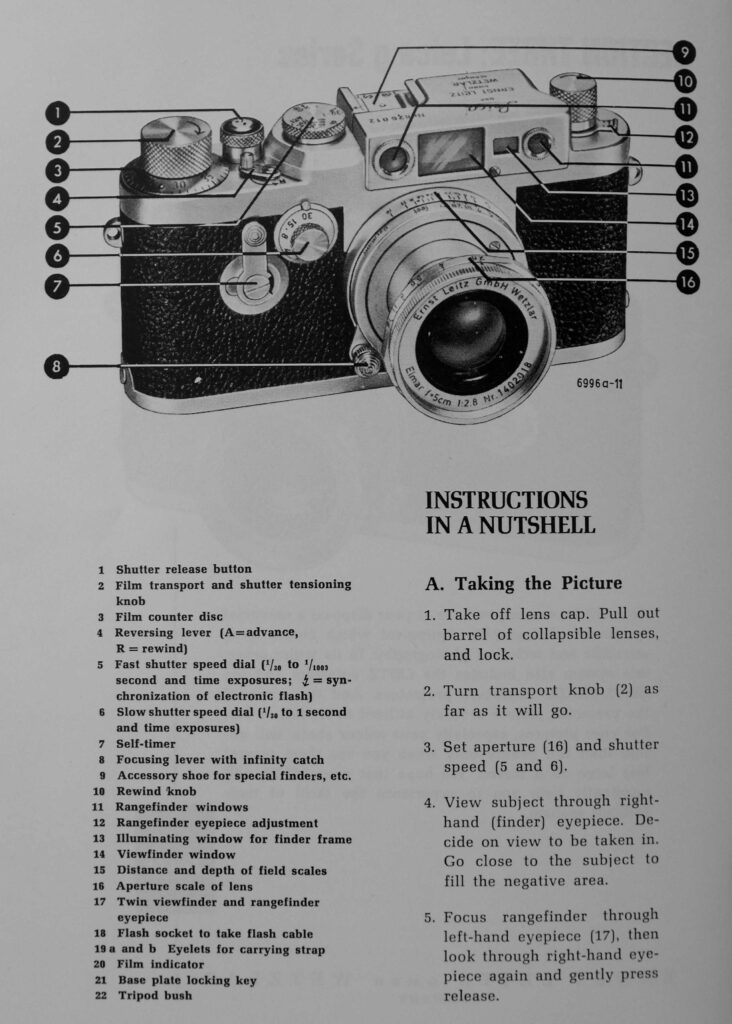

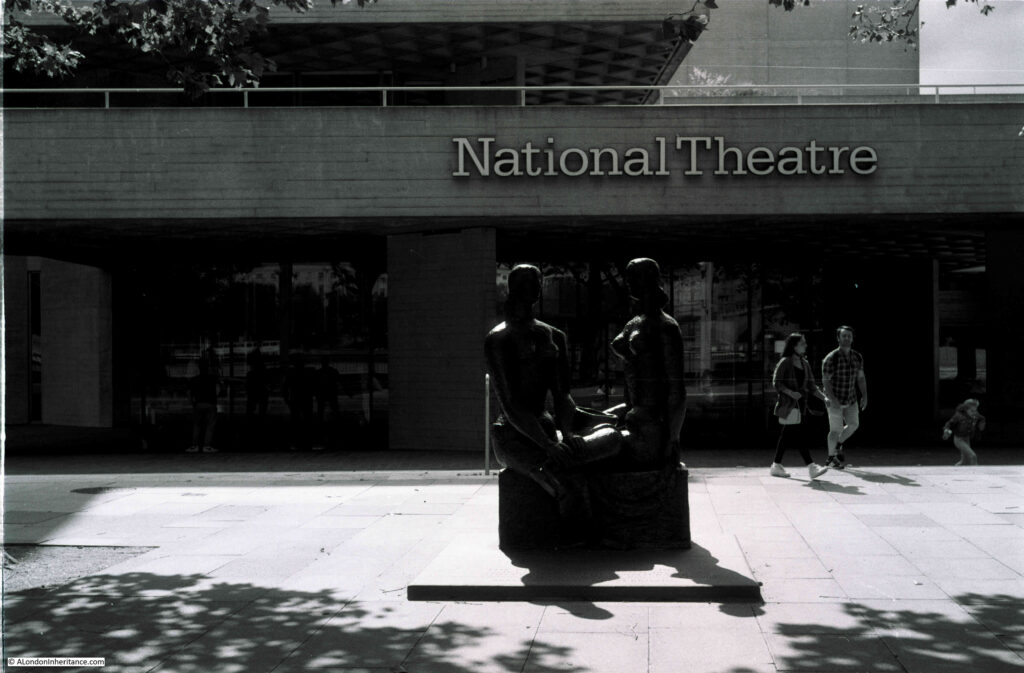

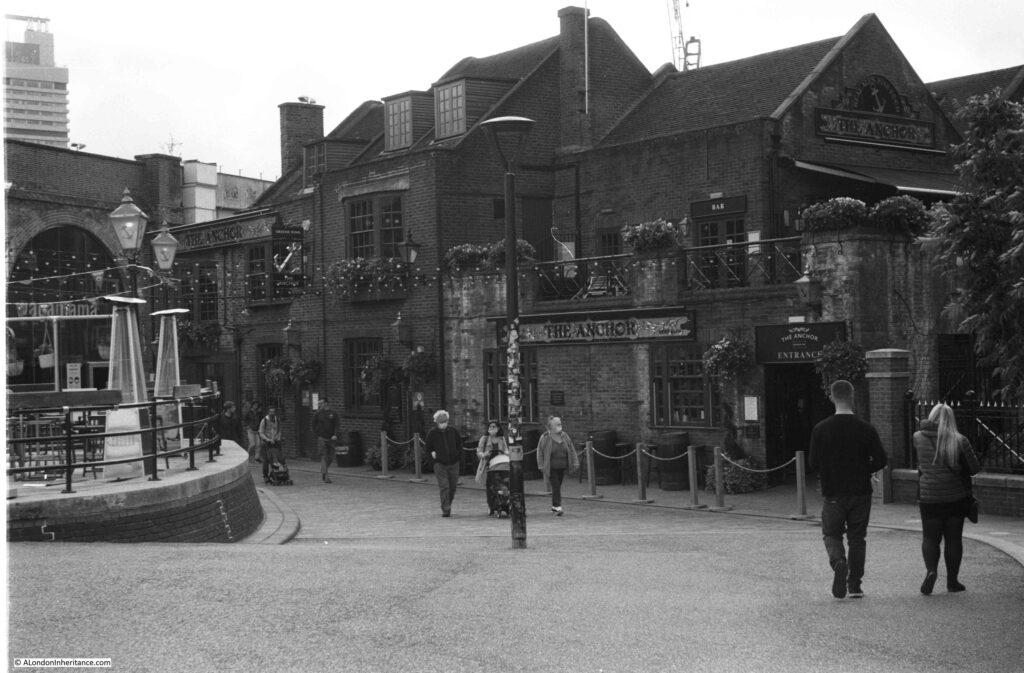

I took a couple of photos during a lunch time wander along the south bank:

The poster was an attempt on the world record, although a search of the online database of the Guinness Book of Records does not bring up any reference, although they do not have data online of all records, and this was 41 years ago.

1979 was the Year of the Child, and 360 children from across the country painted individual posters over a four day period, each showing a different aspect of safety, of the emergency services, or some other form of safety message relevant to a child.

The combined posters measured 800ft by 10ft and circled around the central green space of the Jubilee Gardens.

When I photographed the scene, the Jubilee Gardens were two years old. As their name suggests they were created in 1977 to mark the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, and they quickly became a popular lunchtime spot for the thousands of workers in the Greater London Council, County Hall, or the Shell Centre buildings – the two large office complexes on two sides of the gardens.

To the east of the park (just visible to the right of the first photo), there was a small stage area, and lunchtime concerts were organised by the GLC.

When weather was not so good, for the rest of the working day, and at weekends, the Jubilee Gardens were quiet. County Hall’s conversion into a hotel and centre for tourist attractions, along with the London Eye were still some decades in the future.

The Jubilee Gardens were closed for a number of years during the 1990s as they were one of the construction sites for the Jubilee Line extension which runs slightly to the west between Westminster and Waterloo Stations. An access shaft was dug in the centre of the gardens down to the level of the tunnel workings.

I often wonder if the access shaft is still there, below the surface, when ever I walk across the gardens.

After the gardens were reopened, they did deteriorate somewhat, but underwent a major redesign and restoration project, reopening in 2012, and it is these gardens we see today:

As well as the design of the gardens, their surroundings have changed considerably over the years, and the people who probably make most use of the gardens today are not office workers, they are more likely to be tourists.

The GLC was disbanded in 1986, and the buildings now host functions mainly aimed at the tourist industry.

Shell have sold off most of the space originally occupied by their offices with today only the tower remaining. New apartment towers have recently shot up around the original Shell tower. The following photo shows the southern edge of the Jubilee Gardens:

The view across the gardens from the northern edge, adjacent to the Embankment walkway:

The London Eye now dominates the view across the Jubilee Gardens:

The Jubilee Gardens as an open space date back to just after the Festival of Britain which occupied the site in 1951. The Shell Centre complex was built on part of the Festival site between Belvedere Road and York Road, construction being between the years of 1957 and 1962.

Part of the plan for the development of the south bank was to leave the space between the Shell tower and the river as open space, enabling an unobstructed view of the tower down to ground floor foyer level from the north bank of the river. The following photo from 1978 shows the view. I took this in the spring so the trees are only just starting to come into leaf, so the gardens are almost invisible from the north bank.

From the closure of the Festival of Britain, until the creation of the Jubilee Gardens in 1977, the site was a temporary car park – temporary in that it was never properly constructed as a car park, the space was just for this purpose until a long term use could be found (and financed).

The Jubilee Gardens were part of the Jubilee Celebrations along the South Bank in July 1977, when there were a number of short, informal performances, and if you had been in the gardens on either the 2nd or 9th of July, you could have seen “Morley College Choir, Tilford Bach Festival Choir, Morley Meridian Choir, Morley Brass Band, Morley Jazz Orchestra, along with performances of opera, early music groups with folk, court, ballet and modern dancing”. Morley College is a specialist provider of adult education, founded to address the learning needs of Waterloo and Lambeth, hence the local connection with Jubilee Gardens.

The gardens were the scene of a number of demonstrations during the 1980s. Marches demonstrating against unemployment in the early 1980s and during the miners strike of 1984 to 1985 there were rallies and demonstrations by miners and supporting trades unions in the gardens.

The view across the Jubilee Gardens in 1980.

The stage area can be seen on the right. The area on the left was still used as a car park. I doubt that anyone at the time could have imagined the London Eye being central to this view.

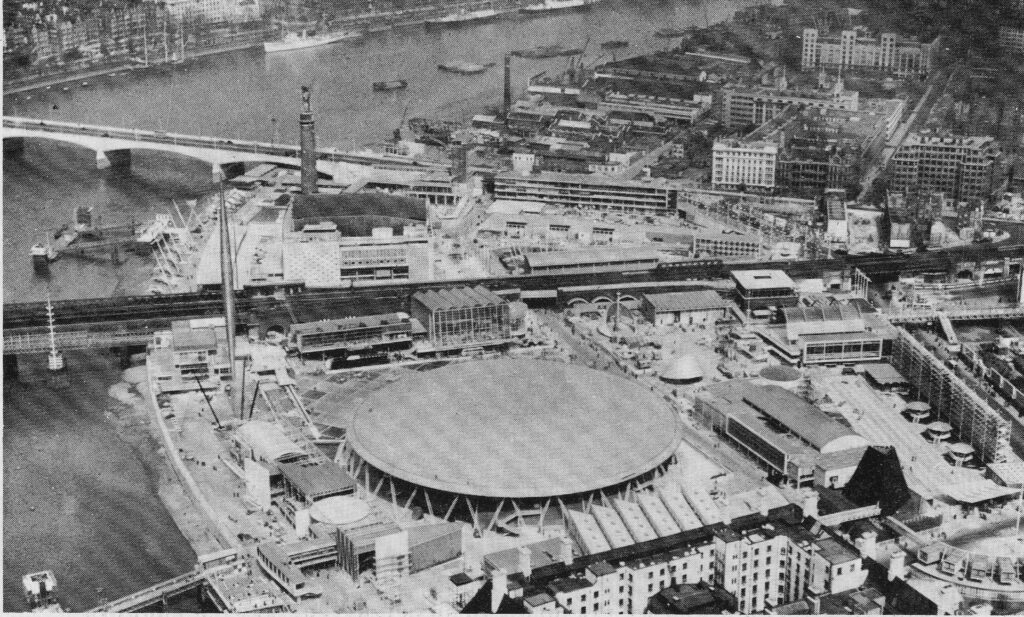

However, as well as being close to the London Eye, the area was the location for one of the key structures of the Festival of Britain, when the Dome of Discovery occupied the space now occupied by the Jubilee Gardens as can be seen in the following photo:

In the above photo, the buildings of County Hall that now face onto the gardens are seen on the lower right of the photo.

The following photo shows the construction of the Royal Festival Hall (in the foreground) and the Dome of Discover, with the buildings of County Hall in the background to confirm that the Jubilee Gardens now occupy the same space as the Dome of Discovery.

One of the reasons that the south bank site was chosen for the Festival of Britain was that the area had been very badly damaged during the war. During, and just after the war, many of the buildings on the site of the Jubilee Gardens had been demolished, with all that remained being a growing pile of rubble, as shown in the following photo by my father – again the buildings of County Hall confirm the location.

The site was completely cleared as shown in the following remarkable photo, which shows the area now occupied by the Jubilee Gardens cleared down to what was probably the original ground level when this was all marsh land.

The river must have flooded over the area at high tide – which explains why if you are at ground level at the edge of the side of County Hall facing the gardens, there appears to be an extension of the Embankment wall running inland alongside the building. It was to keep the Thames out.

This was the first area cleared for the construction of the Festival of Britain, as on the other side of Hungerford Railway Bridge, just behind the Shot Tower is the Lion Brewery, which would also soon be demolished.

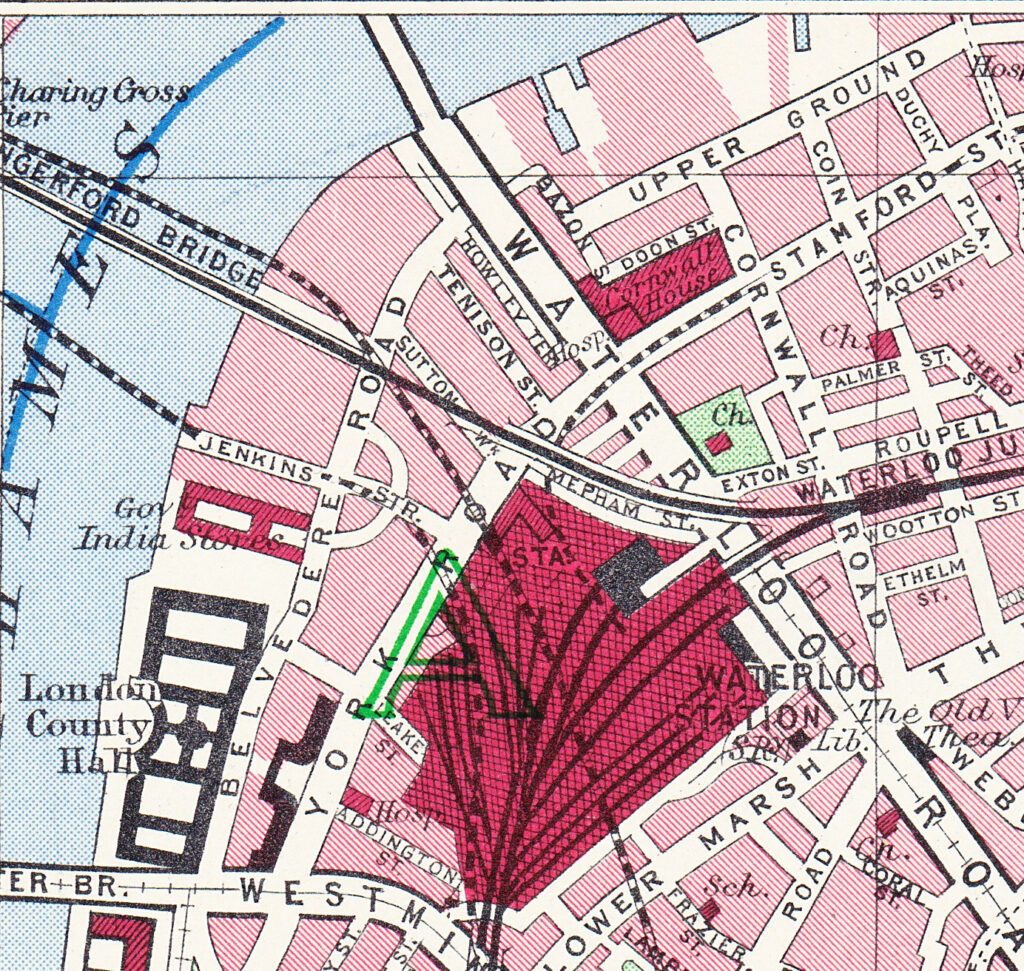

Before the war, the area now occupied by the Jubilee Gardens was mainly warehousing and industrial. A large warehouse – the Government India Stores – occupied the site, along with a now lost street – Jenkins Street, as shown in the following map extract (again the buildings of County Hall provide a point of reference).

The Government India Stores, or the India Stores Depot was built in 1862 on land leased by the Secretary of State for India. The purpose of the building was to hold goods that had been purchased in the UK by the Government of India, prior to shipping to India.

By the end of the 19th century, this was getting to be a dubious exercise with questions being asked in Parliament about why the Government of India was purchasing goods in the UK which could also easily be purchased in India, and would benefit the Indian economy.

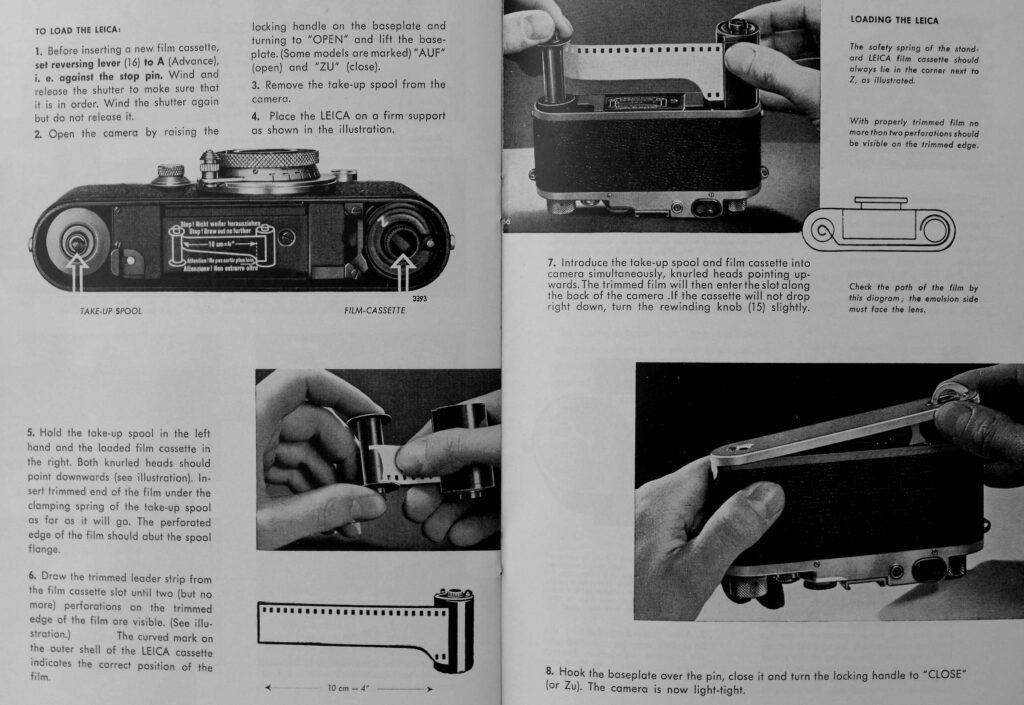

My father photographed the post war remains of the Government India Stores prior to demolition:

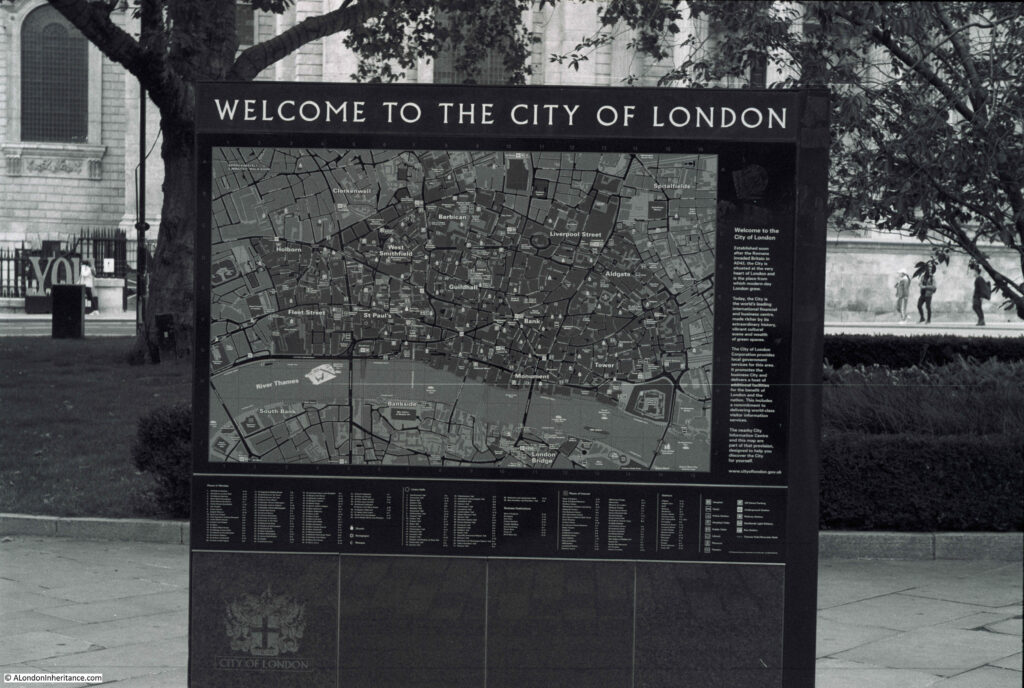

The area occupied by the Jubilee Gardens has long been an industrial site. The following extract from Rocque’s map of London from 1746 shows the sweep of the river as it curves down to Westminster Bridge at lower left.

Where Westminster Bridge lands on the right side of the river, a street named Narrow Wall runs north. The site of the Jubilee Gardens are roughly to the left of the word ‘Wall’. The map shows that the area of land between Narrow Wall and the river was the first to be developed.

Before any buildings had occupied the site, the area had been marsh, and part of the river foreshore. The name Narrow Wall probably refers to an embankment between the river and the land, with a roadway of some basic form running along the embankment.

Just south of the site of Jubilee Gardens, where County Hall is now located and long before any building occupied the location, a Roman Boat was found during the construction of County Hall:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_04_15_53_27D

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_04_15_53_27D

So the area around Jubilee Gardens has a long history and it is intriguing to imagine the Roman boat beached on the foreshore of the Thames and gradually sinking into the mud.

The Jubilee Gardens have seen the dramatic rise in tourism over the last few decades, although they are relatively quiet today as London is still missing the millions of tourists that visit the city.

Their location has seen the London County Council and the Greater London Council come and go, along with the construction of the Jubilee Line extension, the Dome of Discovery and the Festival of Britain. The site has been bombed and was the location of a warehouse for goods bound for India.

They have been the site for demonstrations, a wide range of entertainments, and a green space for office workers to spend summer lunchtimes – and possibly the record breaking World’s Longest Safety Poster,