A Christmas custom for me, growing up in the 1970s, was to watch the BBC’s Ghost Story for Christmas. An almost annual event which usually featured one of the stories written by M.R. James.

Many of these stories followed some general themes. The main character was frequently a reserved antiquarian scholar, the plot often involved the discovery of something which would result in the arrival of a malevolent spirit, stories would often be set in the counties of Norfolk or Suffolk, a cathedral, abbey or university.

Many of these themes came from M.R. James own background.

He knew the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk very well. He was a medieval scholar, and was Provost of King’s College, Cambridge and then Eton. The term Provost is often used for the role of head of a university college or a private school.

His ghost stories appear to have originated from a custom where he would write, then read his ghost stories to friends on Christmas Eve. The first collection of his stories were published in book form in 1904 with the title “Ghost Stories of an Antiquary“.

M.R. James, or Montague Rhodes James, to give him his full name, was born on the 1st of August 1862, in the county of Kent and died on the 12th of June 1936 whilst he was Provost of Eton College.

He was buried in a small cemetery on the outskirts of Eton, so a recent trip to Windsor provided the opportunity to visit his grave, which seemed a suitable Jamesian thing to do in the weeks before Christmas.

M.R. James was buried in the grounds of the Eton Wick Chapel, a short walk from the centre of Eton.

The easiest way to get to Eton is from Windsor where there are car parks and train stations, and it is from Windsor that we started the walk.

The old road bridge between Windsor and Eton is now pedestrianised and crosses the River Thames:

View from the bridge over the River Thames, with Windsor on the south bank of the river, and Eton on the north:

View looking back towards Windsor, with the castle towering above the town:

Eton High Street:

The pedestrianised bridge from Windsor over the Thames runs into Eton High Street. This bridge and street was once an important road as it was one of the main routes for access to Windsor Castle. Follow Eton High Street northwards and it ran up to the Bath Road in Slough, the Bath Road being one of the main routes from London to the west.

Running across the High Street is a small watercourse called Barnes Pool. This flows from the Thames, through Eton, then back to the Thames, and originally turned the southern section of Eton into a small island.

The earliest recorded bridge over the stream dates from 1274, and it has been rebuilt a number of times since, including 1592 when a new bridge was commissioned by Elizabeth I who was concerned about being cut-off in Windsor in the event of a Catholic revolt.

The Barnes Bridge today:

The stream is open water on either side of the bridge, however towards where the stream originates and then renters the Thames, the stream is contained within a culvert which gradually became silted up, and for many years there was no flow in the stream.

In the last few years there has been a campaign to open up the stream. The culvert has been cleared of silt, and Barnes Pool is now flowing through Eton between two points on the Thames:

Whilst Barnes Pool looks a very small stream of water today, before the culverts silted up, the stream could flood during periods of high rainfall, and on the brick wall next to the stream is a marker recording the heights of previous floods, with the highest recorded in 1774 when the flood almost reached the top of the wall (which obviously was not there at the time).

St Mary’s Chapel, Eton:

M.R. James became Provost of Eton in 1918, and in the announcements of his new role, there is no mention of his ghost stories, the first of which were published in book form in 1904. He appears to have been the logical candidate for the role of Provost, as this report from the “The Mail” on Wednesday, 31st of July 1918 explains:

“Dr. Montagu James Appointed – Our Cambridge correspondent is officially informed that Dr. Montagu Rhodes James has accepted the appointment of Provost of Eton as from next Michaelmas Day. Dr. James has been Provost of King’s since 1905, and was Vice-Chancellor in 1913 and 1914.

The appointment of Dr. James has always been regarded as inevitable at Eton, where it will be universally popular. A devoted Old Etonian, and head for the past dozen years of the sister college at Cambridge, he has already been a member of the Governing Body of Eton during that period, and has latterly sometimes presided over it. The selection by the Crown of a layman marks a breach with recent practice, though it is not unprecedented. Dr. James, however, takes high rank as a theologian no less than as a brilliant scholar. Moreover, he has been Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge; so that he will bring to Eton not only a tradition of sound learning, but a great experience of academic administration.”

He was installed as Provost of Eton in October 1918, with the King’s representative present (the Dean of Windsor), and the Headmaster of Eton, with speeches and addresses to the new Provost being read in Latin.

Opposite the chapel is Keates Lane, and this was the route out of Eton to find M.R. James grave:

View from Keates Lane back to the chapel, with buildings of the college on either side of the street:

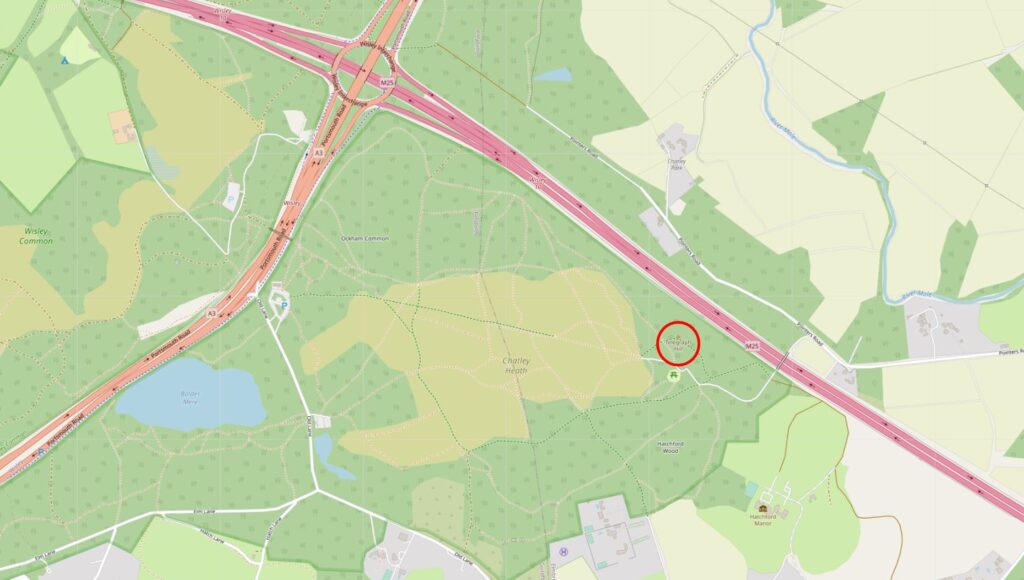

Keates Lane, then bends right and becomes Eton Wick Road, and after a short walk, I came to the chapel and graveyard:

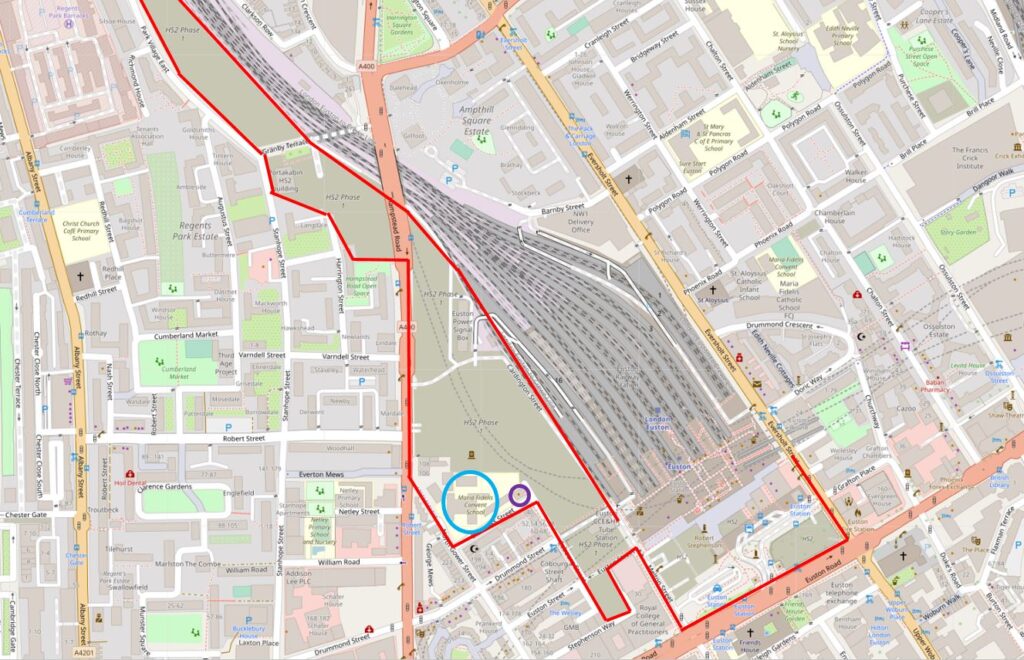

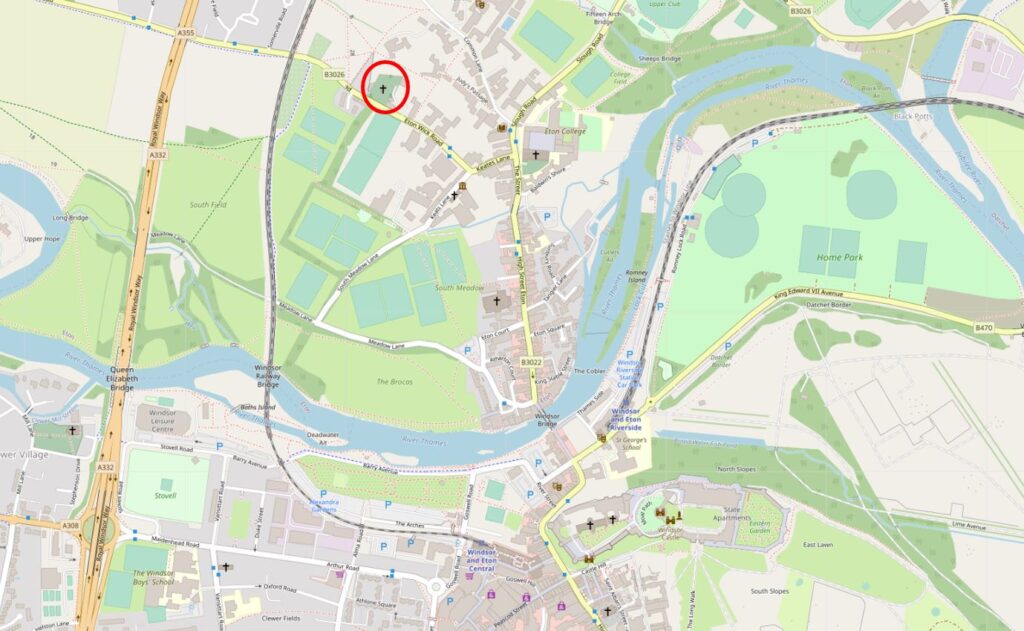

I have circled the chapel and graveyard in the following map. Windsor is to the south of the Thames, with Eton High Street running north, from the bridge over the Thames up to the centre of the town, where a left turn into Keates Lane takes you to Eton Wick Road, and then the chapel (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

Visiting churches, abbeys, monasteries and historic locations in general, as well as the towns and countryside of Suffolk and Norfolk appear to have been passions of M.R. James, and clearly influenced his ghost stories.

I have copies of two guide books that he wrote and which were based on his own travel and research.

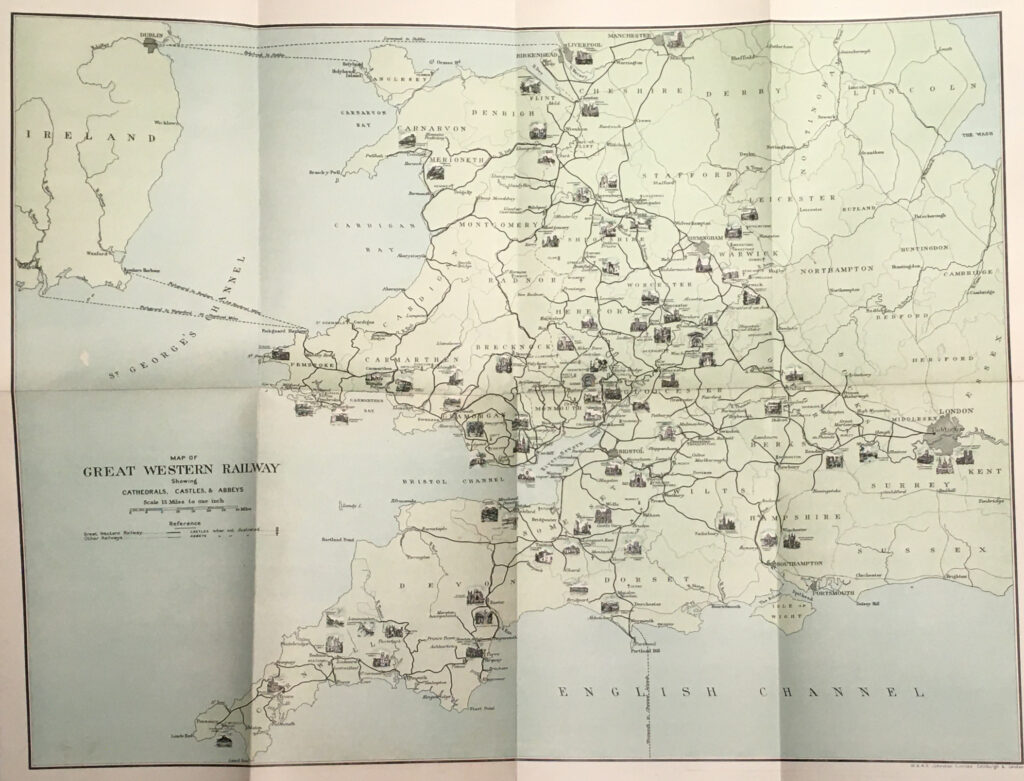

The first, “Abbeys” was published in 1925, rather strangely by the Great Western Railway, Paddington Station, and although the title of the book is simply Abbeys, the focus is on the west of the country, so presumably fitted well with the Great Western Railway network.

The book includes a large map of the Great Western Railway, showing Cathedrals, Castles and Abbeys, so the book really acts as a guide for all the places you could visit by taking a train from Paddington Station.

M.R. James second guide book was of Suffolk and Norfolk, and described as a “Perambulation of the two counties with notices of their history and their ancient builds”. This book was published in 1930 by J.M. Dent and Sons, so was not a guide book for a railway company.

Reading the two books it is clear where much of James inspiration for his ghost stories comes from. His descriptions of Norfolk and Suffolk align with many of his stories, for example, his story “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad” was set on the Suffolk coast, where a Cambridge Professor on a golfing holiday finds an old whistle while exploring the ruins of an ancient Templar building.

He then sees the outline of a person running after him on the beach, and also standing on the beach looking at his hotel room. After cleaning the whistle and blowing on it, he is troubled with bad dreams, sounds in his bedroom and the sheets on the second bed in his room being crumpled as if someone had slept in the bed.

The climax of the story comes on the second night when a figure rises in the room, and the Professor is backing towards a window, only to be saved when another guest bursts into the room.

Although I was too young to see it when first broadcast, the BBC’s 1968 version of the story with Michael Horden playing the Professor is really good and brings across the wild and open landscape of the coast, and the growing tension of the story.

Horden brilliantly portrays a probably rather reclusive, scholarly, professor. A man who is completely confident in his rational view of the world – a view that is completely shaken by the end of the story.

The 1968 version of “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad” can be found on YouTube.

The book also includes drawings of a number of bench end carvings. These are the carved depictions of animals, human figures etc. which can often be found on the end of benches and pews in churches.

These featured in the story “The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral”, where they appear to come alive and haunt a cleric who has murdered an aged Archdeacon at the cathedral

The gate leading from the road into the graveyard and chapel:

The graveyard:

Looking back at the gate into the graveyard:

M.R. James grave is at the back of the graveyard, and similar to what could be expected in an M.R. James ghost story. It is in a rather overgrown part of the graveyard. Being December, much of the vegetation had died down, but I still had to walk through Ivy and the thorn covered stems of dead bramble growth.

In the following photo, the gravestone is the small, white stone on the right:

The gravestone of Montague Rhodes James:

The grave is surprisingly simple. The gravestone records the dates of his birth and death, the dates of his time as Provost in Cambridge and Eton, along with the following inscription:

“No longer a sojourner, but a fellow citizen with the saints, and of the household of god.”

The area around the grave is overgrown, however the gravestone is clean and in good condition, which I believe is down to a campaign some years ago to clear the grave, although nature has now reclaimed much of the space.

Fortunately I did not find a whistle sticking out from between the leaves of the ivy.

A number of newspapers carried news of the death of M.R. James, and a brief obituary:

“DEATH OF PROVOST OF ETON – Mediaeval Authority and Prolific Author. The provost of Eton, Dr. Montague Rhodes James, died at his house, The Lodge, Eton, yesterday. he was 73.

Dr. James had been in ill-health since January of this year, and in April his condition became serious, but he made a satisfactory recovery.

As recently as last Thursday, at the Fourth of June celebrations, he was wheeled round the college playing fields, where he talked to a number of old Etonians.

Immediately he died the Eton flag, bearing the arms of Henry the Sixth, founder of the College, was lowered to half-mast over Upper School.

Dr. James was one of the most erudite antiquaries and one of the most prolific authors of his age. The list of his literary works fills nearly a page of ‘Who’s Who”.

He was an authority on ancient Christian manuscripts, and no surprise was evoked when in 1930 the Order of Merit was conferred upon him in recognition of his scholarship and of his eminent contributions to mediaeval history.

Ghost Stories – These serious studies, however, did not represent the sum total of his literary activity. He found time to write ghost stories – stories which would have won him wider fans but for the great reputation which he had earned in other spheres.

It was at Eton that Dr. James was educated, proceeding afterwards to King’s College, Cambridge, where he had a distinguished career, gaining the Caius Prize in 1882, and becoming Bell Scholar in 1883, and Craven Scholar the following year.

He was Provost of King’s from 1905 to 1918, and Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University from 1913 to 1915.

Among other offices he held was that of a Trustee of the British Museum. His human quality was shown by his influence on youth.

‘The best things in life are not cars, wireless, flying, dirt track, or any other racing, league matches, or the pursuit of wealth’ he once said.

‘The best things are presented by the Bible, Shakespeare, Handel and Dickens, the Elgin Marbles and Salisbury Cathedral, the open country, the sea and the stars; the knowledge that all these may be made to disclose; honest games which are played and not merely looked at.’

His recreations were patience and piequet.”

Many aspects of his life can clearly be seen in his ghost stories. His love of Norfolk and Suffolk, religious buildings, mediaeval history, the academic life and institutions such as Cambridge and Eton.

What is not clear is how similar to the rationale scholar (the lead in Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You) he was, or whether he had some belief in the supernatural, however I suspect the sentence “the knowledge that all these may be made to disclose” from his obituary hints more towards the rationale scholar.

For me, I have to thank M.R. James for some of the best programmes of Christmas TV as I was growing up, as well the published versions of his ghost stories which I have read and reread several times.

The British Film Institute have a brilliant collection of these programmes on DVD, they can be found here. They are well worth a watch during the dark winter’s evenings.

As well as M.R. James, the 1970s were a golden period for TV ghost stories, such as Charles Dickens story the Signalman with Denholm Elliot.

There were also other programmes, some of which had a bit of a moral story to them. Many of these have been on YouTube although several have now been removed due to copyright claims by the BBC.

One that is still (currently) online is The Exorcism, part of the BBC’s Dead of Night series. Broadcast in 1972 it tells the story of a couple who have moved from London and restored a derelict cottage in the Kent countryside – “still within easy distance of London”.

Another couple arrive and during the course of a dinner party, the cottage starts to take on a malevolent character, and the end of the story reflects the story of some previous occupants.

I do not beleive this is on DVD yet, but would be well worth a purchase. As well as the clothes and attitudes of the early 1970s, it also offers a view on those with money who were starting to move out of London and buying up and restoring properties in the surrounding counties. The programme can currently be found here.

Another was “The Stone Tape” which told the story of what we would now call a technology startup, who were establishing a research base in a country house, part of which included some ancient walls.

The Stone Tape has Jane Asher in the lead role, and who had a mysterious fate at the end of the programme. It was written by Nigel Kneal and in many ways builds on his earlier story for Quatermass and the Pit, where ancient memories are still retained in their surroundings and can continue to influence the present. The Stone Tape is available online as a DVD, and is currently on YouTube here.

The Ghost Story for Christmas format has been revived over recent years, with Mark Gatiss recreating a number of M.R. James stories as well as some originals.

As for me, I am on the sceptical side, although I do know a number of people who claim they have seen ghosts.

One of the most convincing, and my own Ghost Story for Christmas was when I was driving down a country lane at night. There were stories about the lane, but the person in the car with me was unaware of them. As we drove up the lane she asked me if I had seen the person in the hooded yellow anorak walking along the side of the road. I had seen nothing even though the car lights were on full and it was a narrow lane, and there was nothing to be seen in the red glow of the rear lights.

And with that, and for my last post of 2022, can I wish you a very happy and peaceful Christmas, however you are celebrating (or not), and wherever you are, and thanks for reading my posts over the year.