A mix of subjects in this week’s post.

Firstly, if you would like to hear me say erm far too many times whilst I talk about the blog, I had a chat with Liam Davis who hosts a weekly podcast on Shoreditch Radio, where he invites guests from all walks of life to talk about London.

There is also a good discussion with Feargus Cribbin of the London Pub Map.

If the embedded widget below does not work, you can find the podcast at this link.

A Wet January Evening in the City of London

Not the most promising of headings, but hopefully I will show you why it is worth it.

The period between Christmas and the first full working week in the new year is a strange one in the City of London.

There are not too many people around, there will be those who have taken an extended break over Christmas and the first few days in January, also, working from home is a very attractive way of working at this time of year.

Although Christmas is rapidly fading from memory, there are still plenty of decorations and lights. Add to that a very wet start to the year, and an evening when the rain gets heavier by the hour, and the City takes on a very melancholy appearance.

The majority of people on the City’s streets are taking the sensible approach of heading home as quickly as possible, however it is also a good time for a little exploration.

Personally, I prefer the summer. A bit of warmth, plenty of sunshine, long evenings, however London looks good at almost any time of year, and to demonstrate, I took a walk from Liverpool Street down to the Bank, taking a series of photos as I went, with light rain to start, and heavy rain at the Bank preventing a longer walk.

I started at Exchange Square, which is an open space between office blocks at the end of the shed over the platforms of Liverpool Street Station.

It is a very unique place, providing an unusual view of the station and the structure of the roof above the platforms. I have written a dedicated post about the area, which you can find here, but the purpose of my latest visit was just to admire the view.

The trees in Exchange Square are currently decorated with lights:

The view from this space is good during daylight, but after dark it takes on a very different aspect, with the lights of the square, the station, and the tower blocks behind.

I assume that if the proposed development above Liverpool Street station goes ahead, then the view of the office blocks in the distance will be blocked by the new tower built over the station:

From the fencing between the square and the station, we can look down on the platforms:

Artificial lighting after dark brings out a different level of detail within the roof over the station platforms:

Exchange Square lights:

There are plenty of people using the station, but not as busy as on a working day outside of the Christmas / New Year period:

The McDonald’s at the station entrance:

One of the good things about walking while it is raining are the reflections of lights on the surface of the streets, creating pools of colour. This is by one of the entrances to Liverpool Street underground station, with the Railway Tavern at the corner on the right:

Entrance to Liverpool Street Underground Station:

View back to the station entrance, with purple lighting, and the brightly lit interior of the station in the background:

Entrance to the office building that is on the site of Broad Street Station:

View back towards Liverpool Street Station. The alternative view, if the proposed development goes ahead, can be seen in this pdf. The view does not seem to appear on the projects website, only in the pdf of Exhibition Materials.

Taxis waiting outside the station:

The view along Bishopsgate:

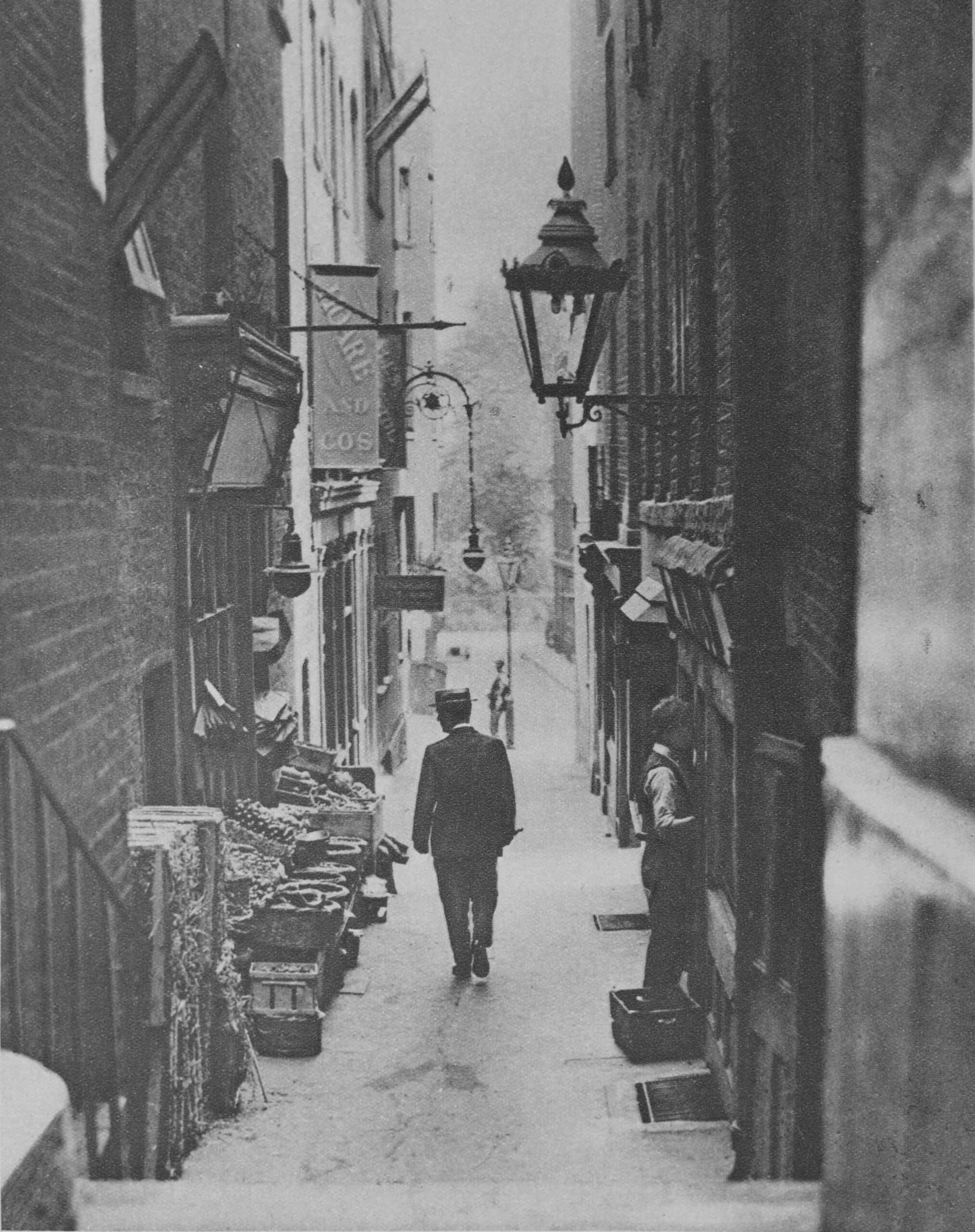

The main streets are much quieter than usual, and the alleys and courts that can be found across the City are dead:

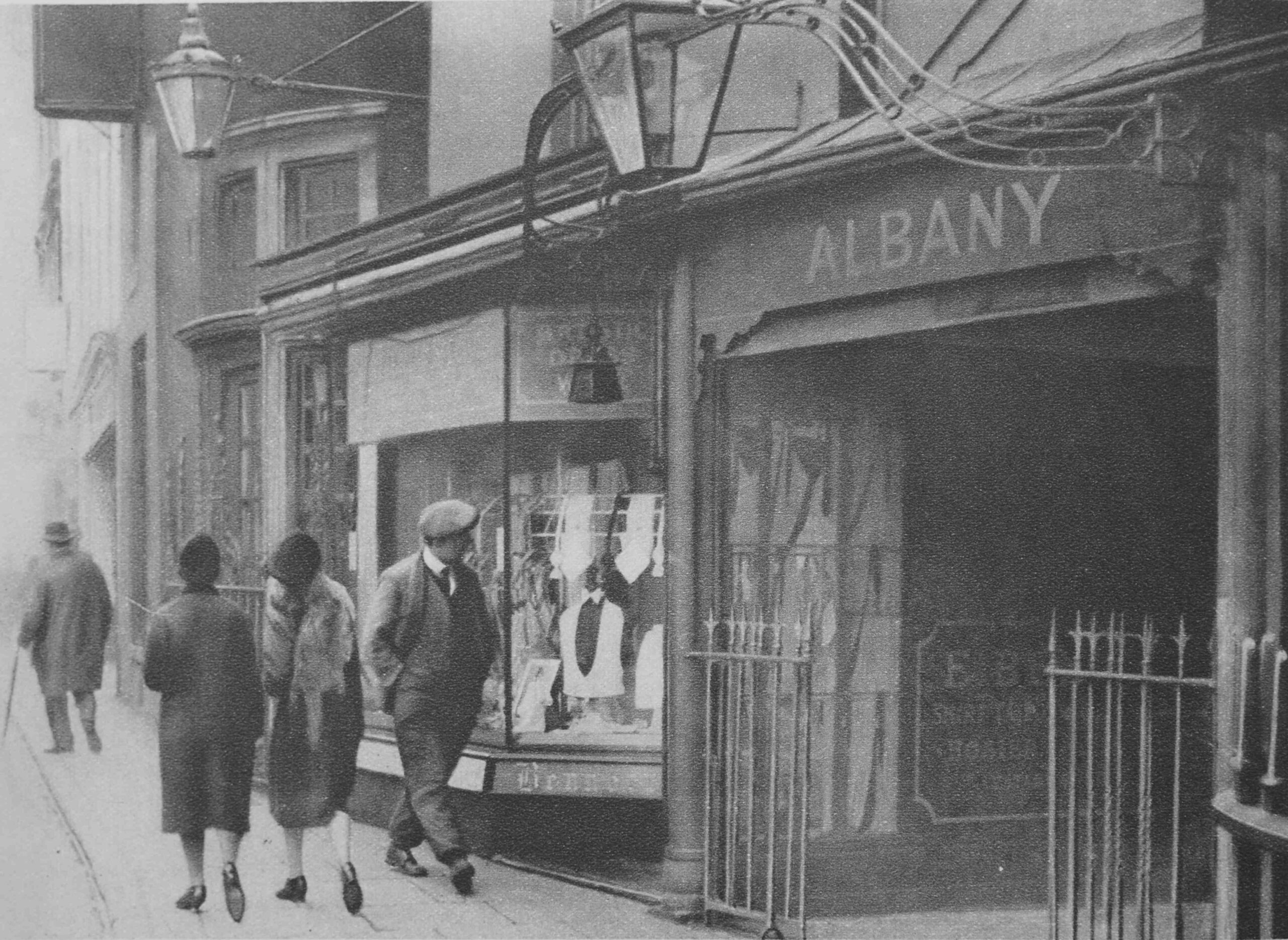

Ball Court, leading off Cornhill:

The tragically closed Simpsons, in Ball Court:

View east along Cornhill:

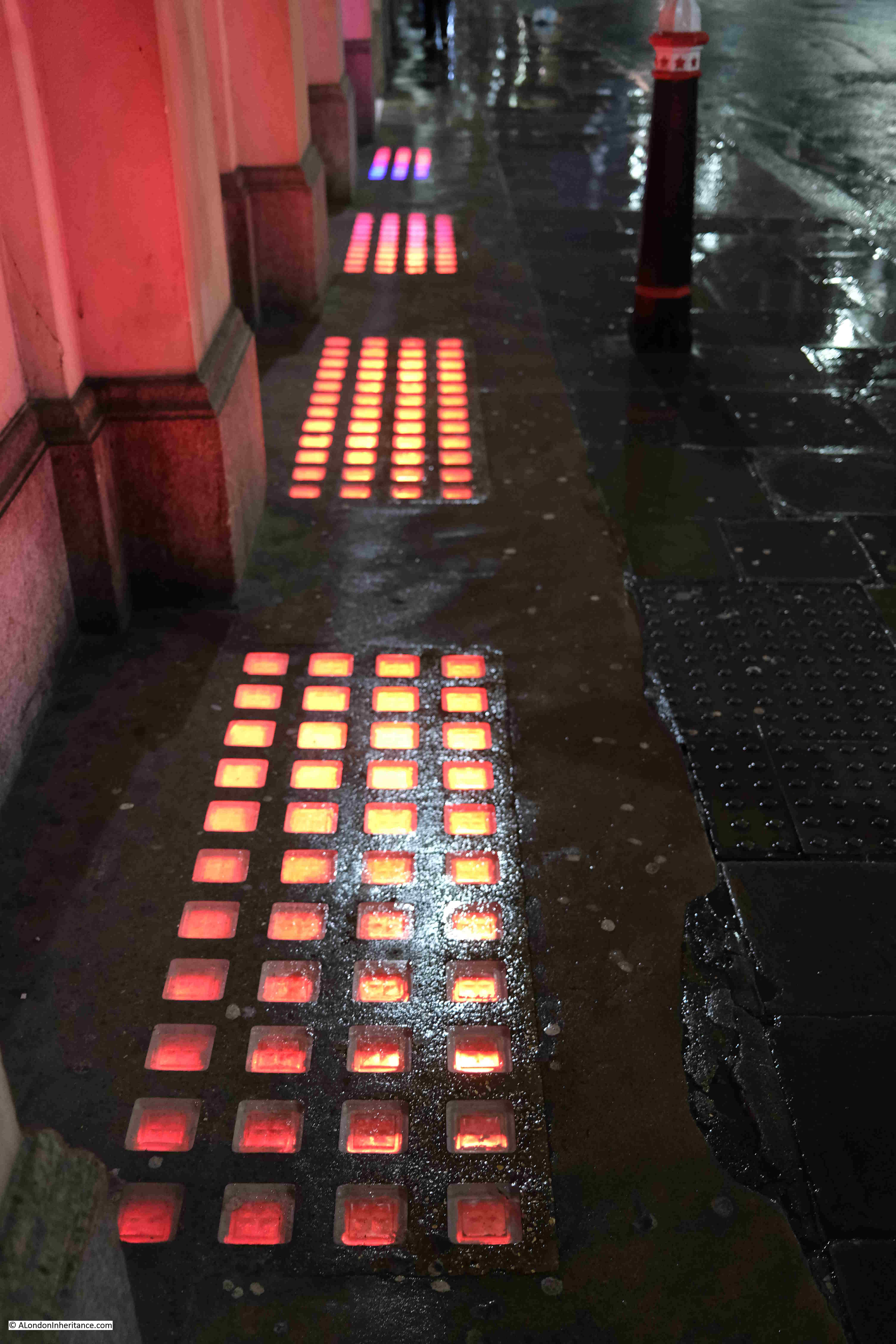

Colour from the basement:

Cornhill looking west towards the Bank junction, with St. Paul’s Cathedral just visible in the distance:

At the rear of the Royal Exchange:

The towers of the City above the “relatively” low rise buildings around the Bank:

At the Bank junction, in front of the Royal Exchange looking along Cornhill, and the rain was getting heavier:

The Royal Exchange with the towers of the City:

Looking down Lombard Street:

No. 1 Poultry, between Poultry (right) and Queen Victoria Street (left):

A final look back towards the east of the City:

The rain was very heavy by the time I reached the Bank, and as water and the electronics in a camera do not mix that well, I joined the few remaining commuters walking into the Bank station to head home.

The Festival of Britain – Land Travelling Exhibition

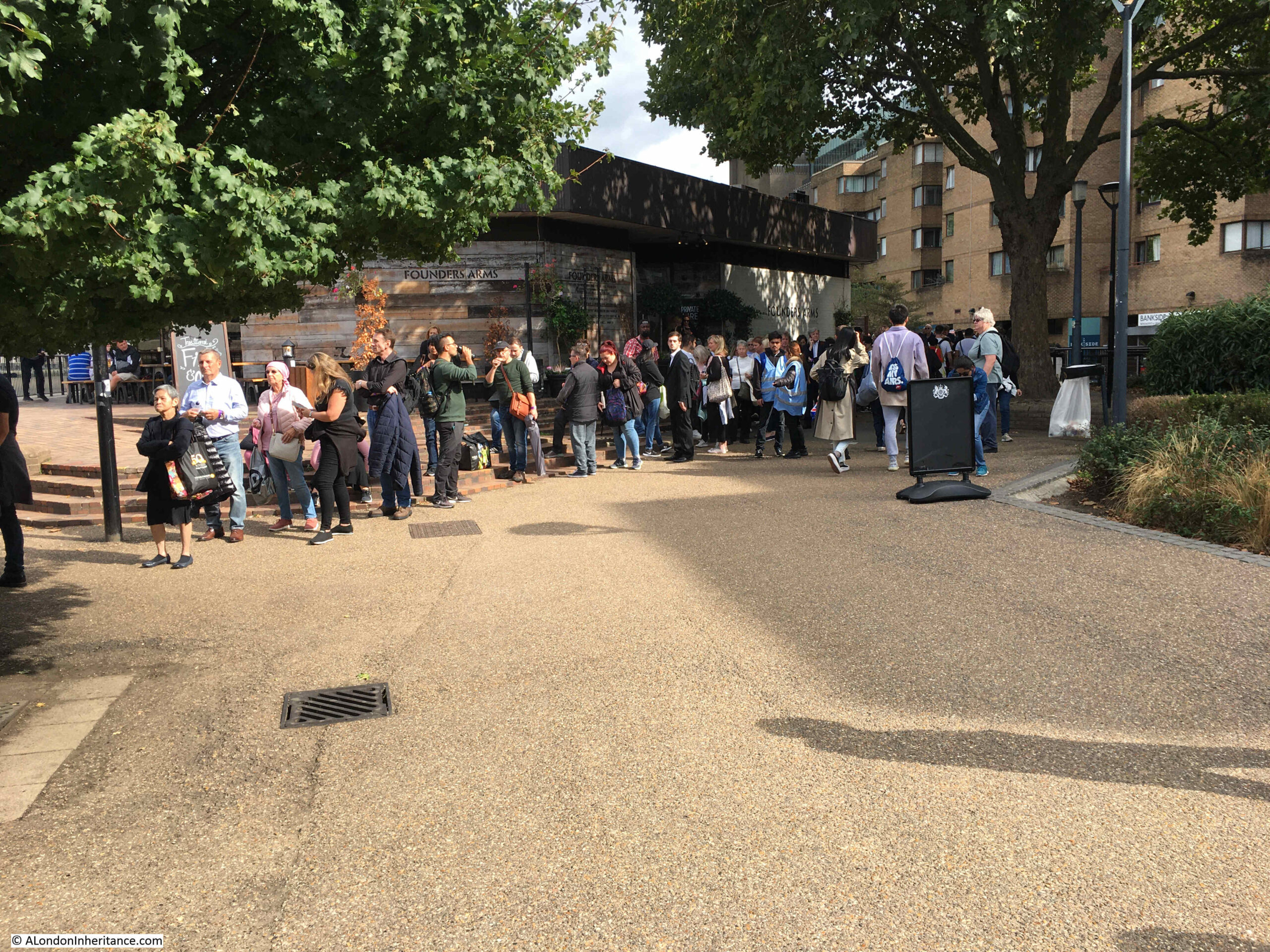

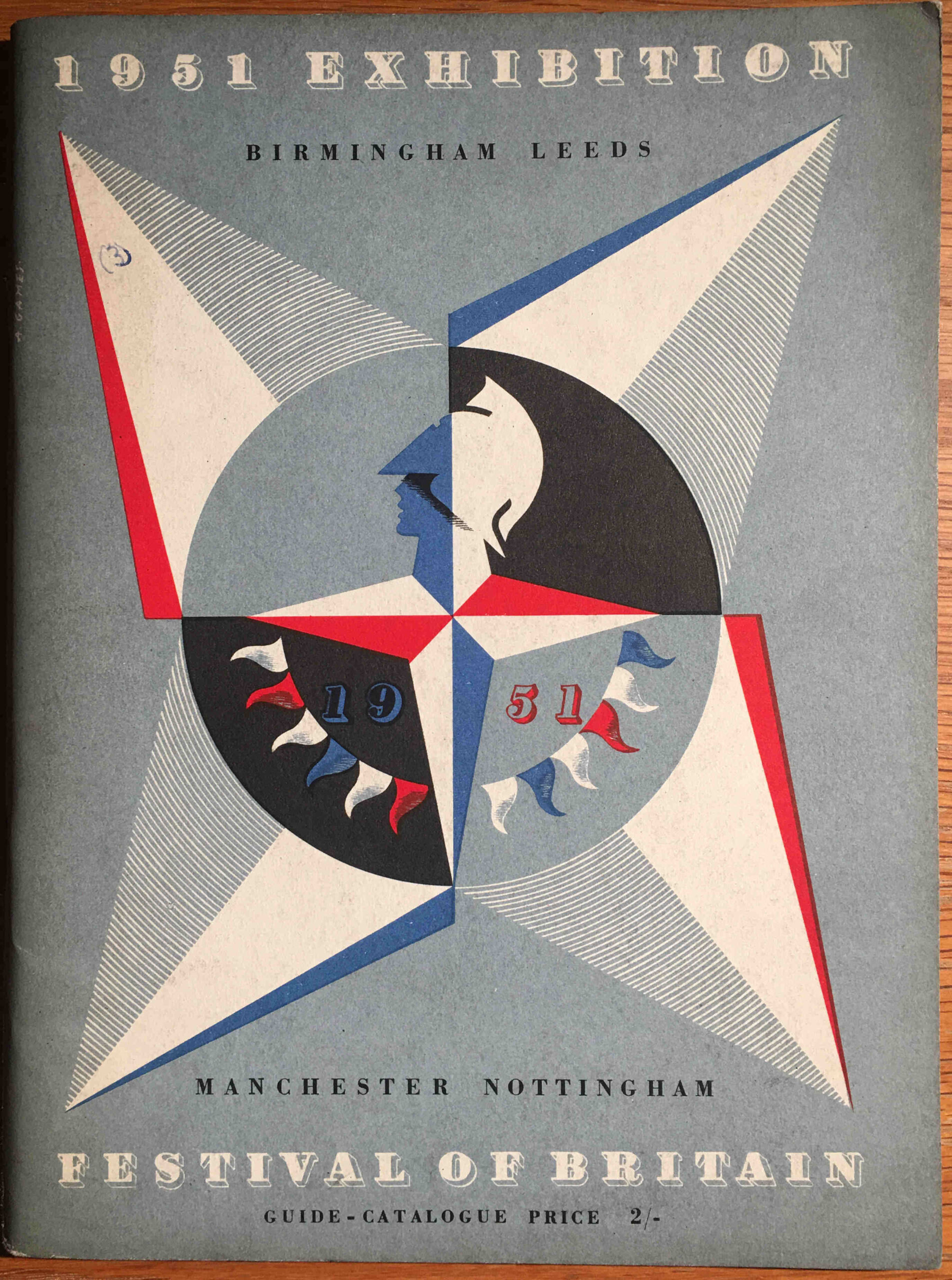

If you have followed the blog for a few years, you will know that I am really interested in the Festival of Britain. The primary site for the festival in 1951, was on the Southbank, in the area between County Hall and Waterloo Bridge.

There were though festival sites all across the country, as the intention was for the country to be involved, not just a London centric festival.

Each of the main festival exhibitions had their own festival guide book. All were based on the same format and design as the Southbank festival site, but with a different colour to the cover page where the Abram Games famous festival emblem featured.

I have been trying to collect all the festival guide books for some years, and I recently got hold of a copy of the guide book for the travelling element of the 1951 exhibition:

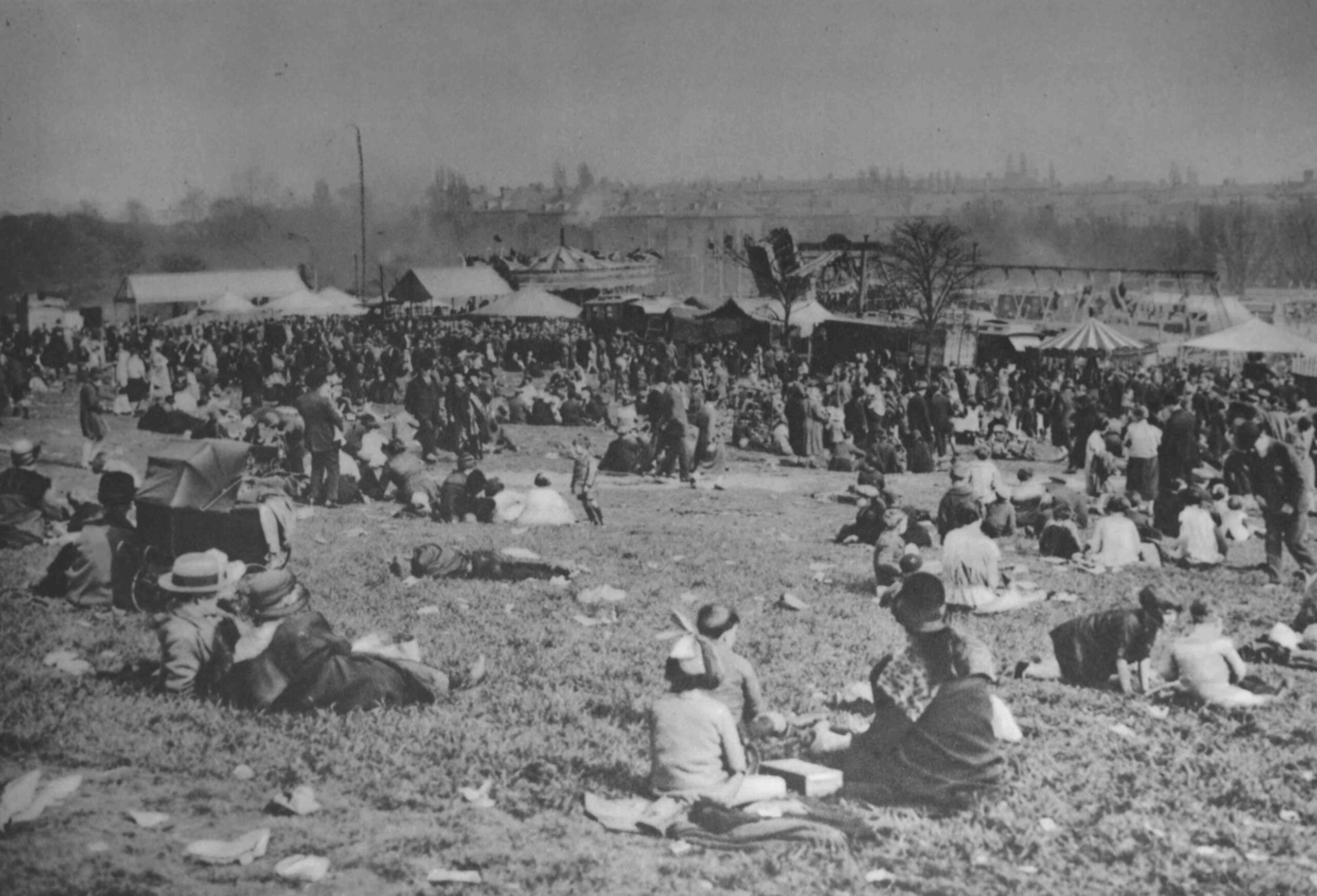

This guide book covered the land travelling exhibition, which visited Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester and Nottingham. As the land travelling exhibition, this would reach major inland cities, where the exhibition on an old aircraft carrier covered major coastal locations (link to this at the end of the post).

The introduction provides the background to the travelling exhibition:

“The Festival Exhibition is visiting four of our major inland centres of industry: Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham and Nottingham. It is therefore appropriate that the main theme of this Exhibition should be the British people and the things they make and use: our past and present achievements in technology and industrial design, and how these provide us to day with manifold opportunities to enrich our daily lives.

The things that will be seen in this Exhibition are not ordinary, average products, but some of the best things that this country is producing at the present time. They are things that we can be proud of, that can inspire and fill us with confidence in the future; and they are a challenge to British industry to emulate the achievements shown here.”

For a travelling exhibition, this was a complex undertaking with thousands of display items grouped into sections as the visitor walked through the exhibition.

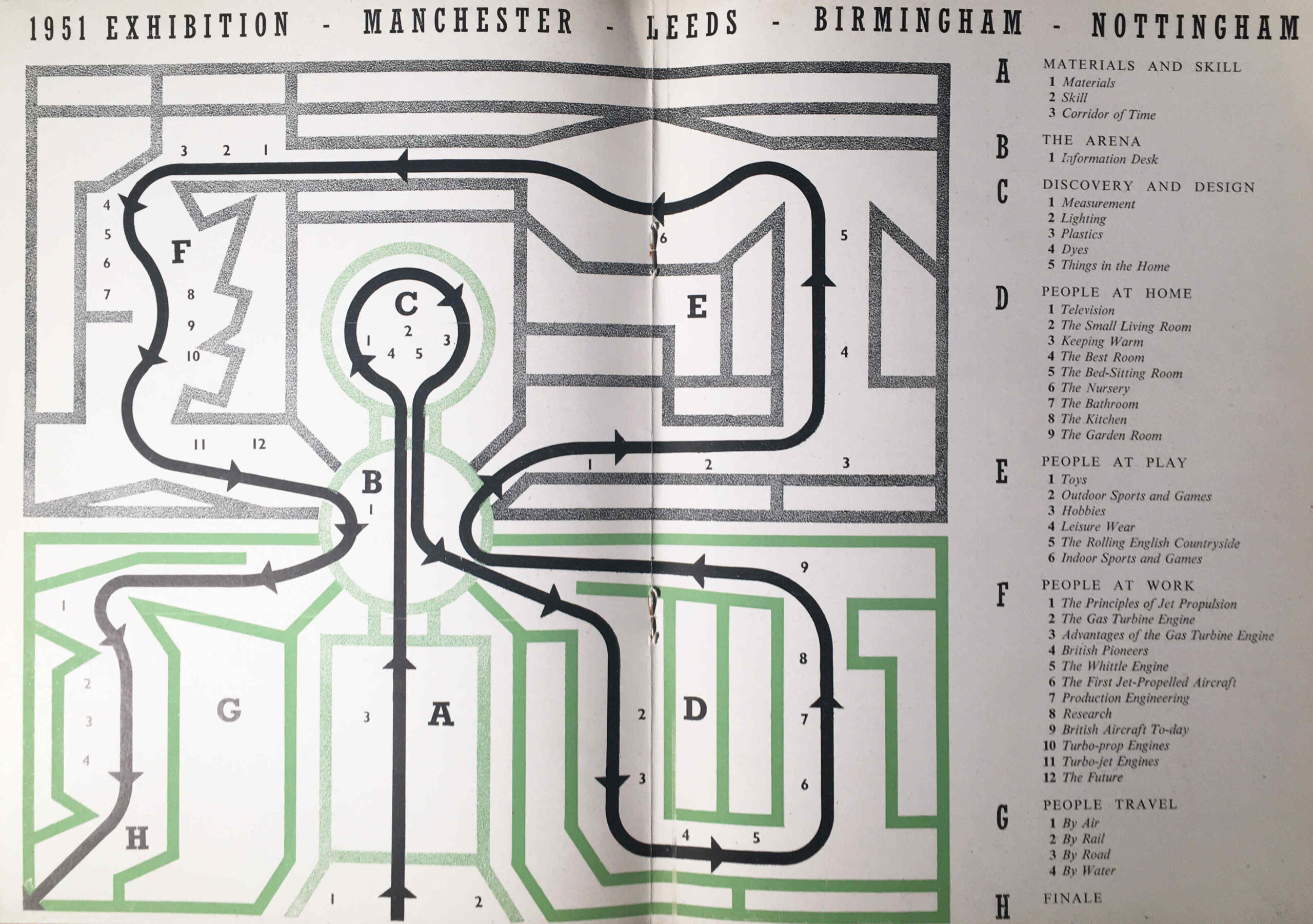

The themes were: Materials and Skill, Discovery and Design, People at Home, People at Play, People at Work, People Travel, and the route and individual displays within each section are shown in the following double page map from the guide book:

The focus on technology and industrial design was appropriate for the locations of the exhibition as these were still major industrial centres. It also followed the overall theme of the future, presenting an optimistic view of the future following years of war, rationing and austerity. An attempt to show what the country could make, as there was still an urgent need to reduce imports, grow exports and sell for foreign currency, and to provide a unifying experience which would involve everyone across the country.

Unlike the Southbank Festival guide book, which contained long written sections describing the displays, the guide book for the Travelling Exhibition was mainly a catalogue of all the individual items on display, however it does contain some brilliant drawings of the exhibition areas.

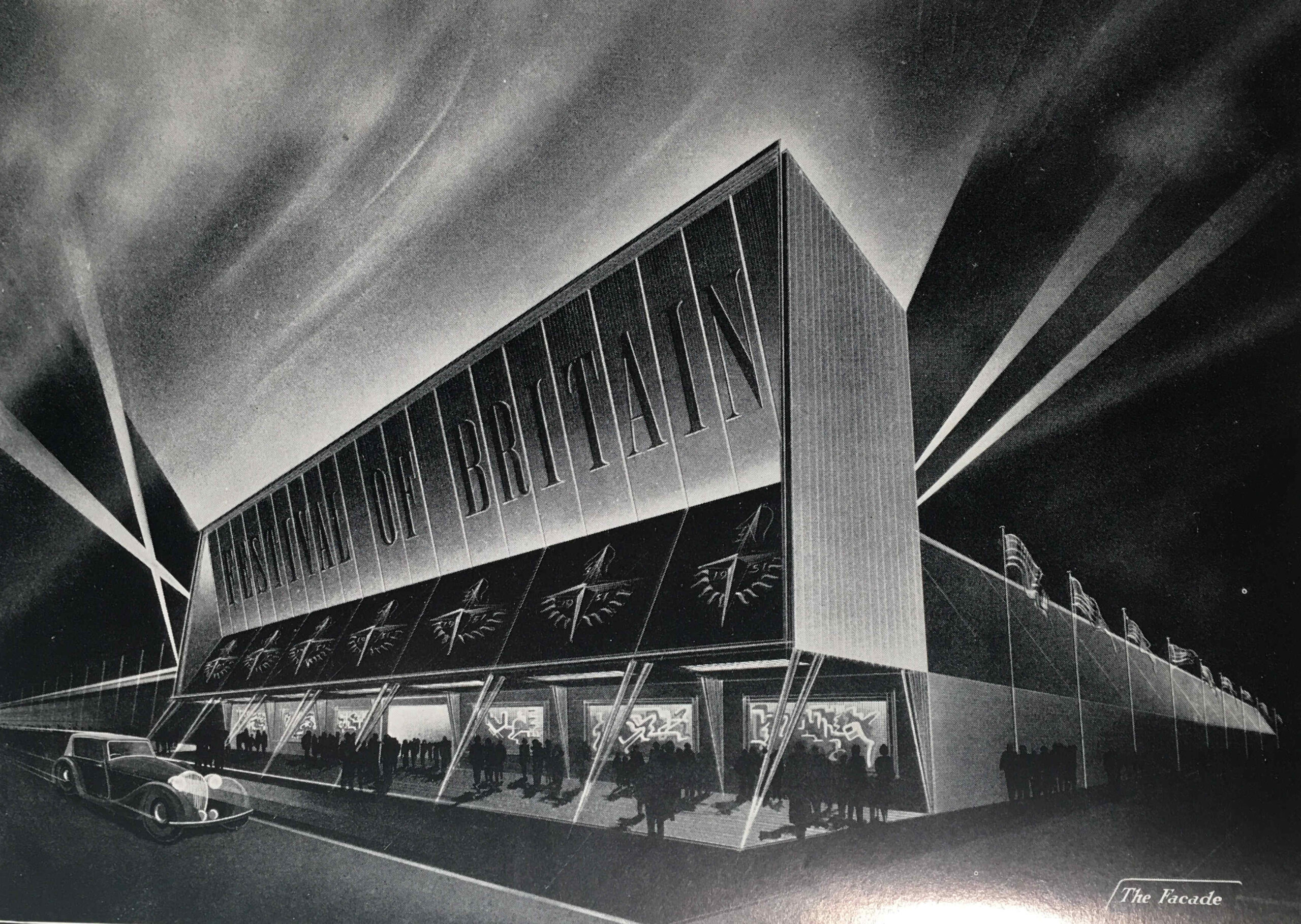

The following image is titled “The Façade”, and shows the main entrance to the exhibition:

The image looks as if it is a Hollywood film premier rather than an exhibition of technology and industrial design.

The timetable for the travelling exhibition was as follows:

- MANCHESTER – At the City Hall, Deangate. Open from Thursday, 3rd May to Saturday, 26th May inclusive

- LEEDS – On Woodhouse Moor (Woodhouse Lane and Raglan Road Corner), Leeds. Open from Saturday, 23rd June to Saturday, 14th July inclusive

- BIRMINGHAM – At the Bingley Hall, King Alfred’s place. Open from Saturday, 4th August to Saturday, 25th August inclusive

- NOTTINGHAM – At Broadmarsh, Lestergate, Nottingham. Open from Saturday, 15th September to Saturday, 6th October inclusive.

The exhibition was open seven days a week, with a morning start, and closing at 11:00 pm, including Sunday, although on Sunday’s the exhibition opened at 2:30pm, as I assume there was still an expectation that people would be going to church on a Sunday morning.

The travelling exhibition was not the only Festival of Britain event organised in these cities, for example, in Birmingham, newspapers were also advertising other Festival of Britain events such as a City of Birmingham Show in Handsworth Park, with events including a dog Show, a Rabbit Show and ending with fireworks. There was also a military tattoo at the Alexandra Sports Stadium and a Festival of Opera and Drama at the Midland Institute and Moseley and Balshall Heath Institute.

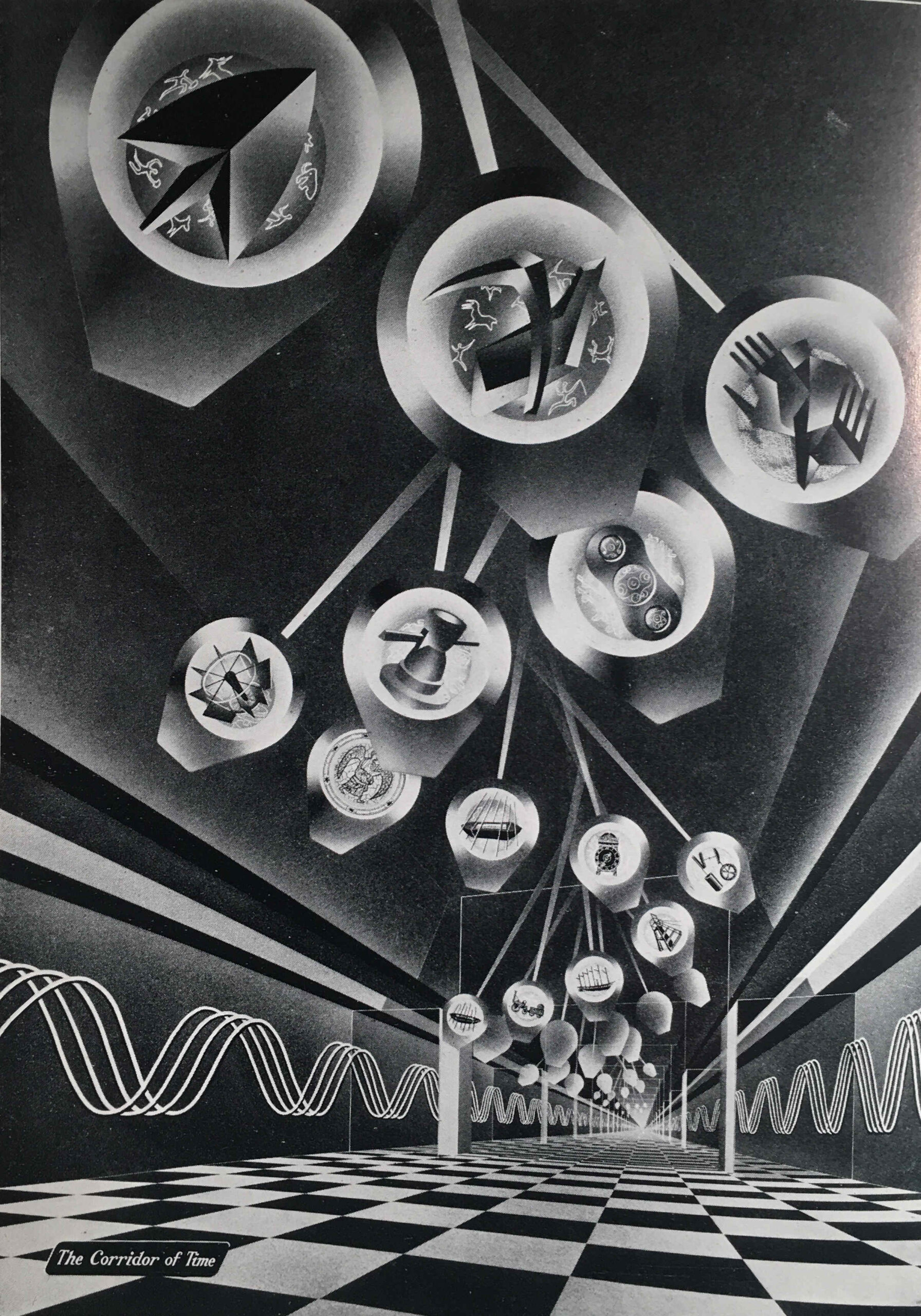

The next image shows the Corridor of Time:

The Corridor of Time was introduced in the guide book as follows:

“The things that have been made in each age have depended upon the degree of man’s mastery over the materials of the earth and the development of his skill in making and using tools and machines. The story of the ascent of man, the ‘tool-using animal’, from the most primitive times to the present day is told in striking and symbolic form in the Corridor of Time. As we advance with time and see the achievements of the past mirrored in the future, we cannot but be optimistic of the possibilities for man that lie ahead.”

At the end of the Corridor of Time the visitor entered the arena where there was an information desk where “industrial enquiries will be directed to a special information room staffed by representatives of the Council of Industrial Design and of industry”.

It is interesting as to who the exhibition was aimed at, as at times the guide book almost sounds like a description of a trade show, rather than an exhibition that was aimed at the general population.

To help people attend the exhibition from the towns and villages surrounding the four cities, British Rail offered cheap day return tickets, and for Birmingham this offer applied to all stations within an 80 mile radius of the city.

The following image shows “The Arena” which led from the Corridor of Time to the rest of the exhibition:

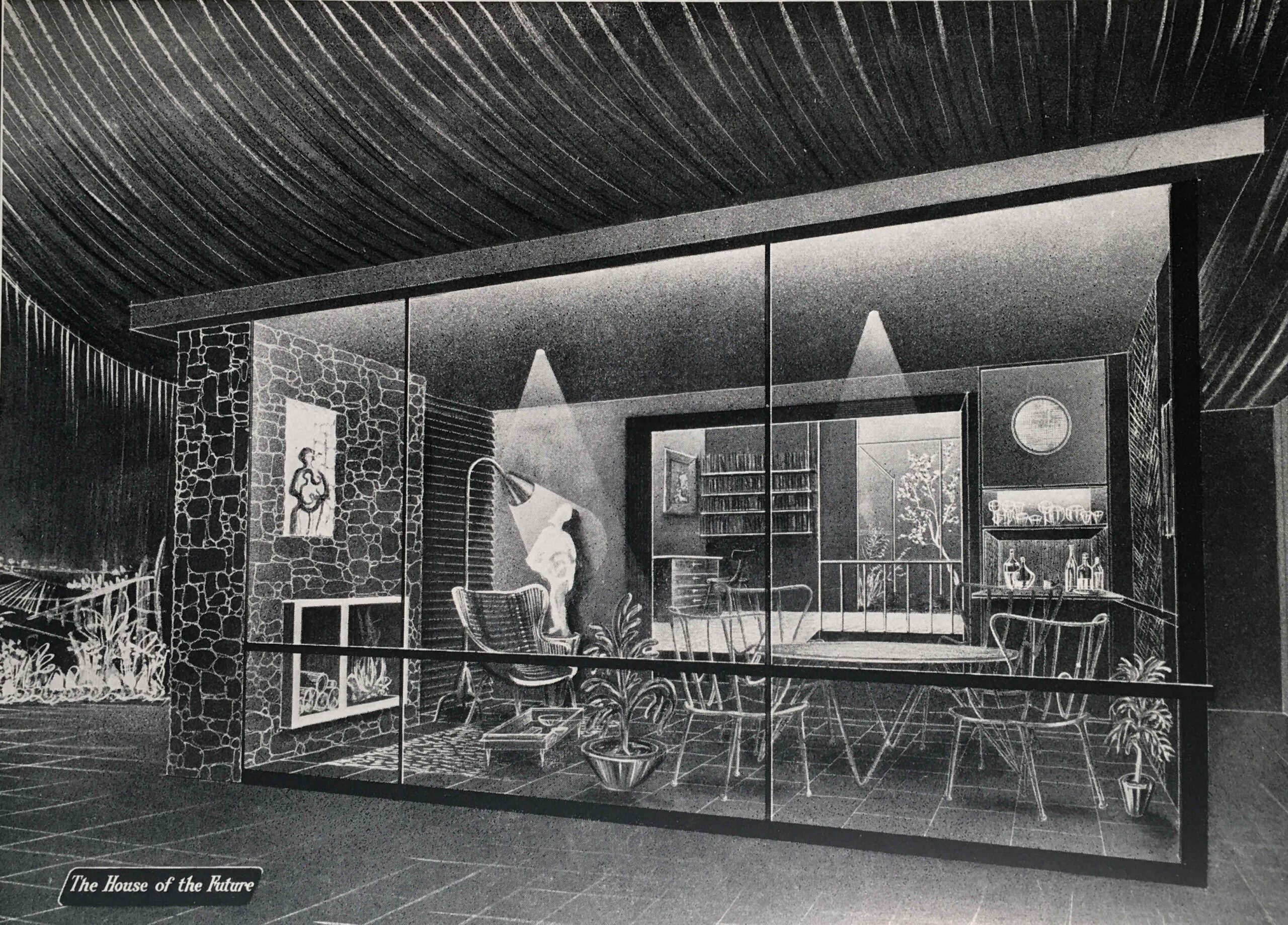

From the Arena, we enter the “People at Home” section of the exhibition, which in the guide book is illustrated by an image of “The Garden Room” of the “House of the Future”:

The Garden Room is a view of what would be happening in the future with the popularity of conservatories and large windows facing onto a back garden, however in the exhibition there was a recognition of the housing problems that the majority of the population continued to face:

“THE BED-SITTING ROOM – With smaller houses and scare accommodation, this form of room has taken on a new importance in recent years. Special efforts and imagination can make the bed-sitting room very congenial, either for the adult living apart from the family or as a place of privacy for the older child.”

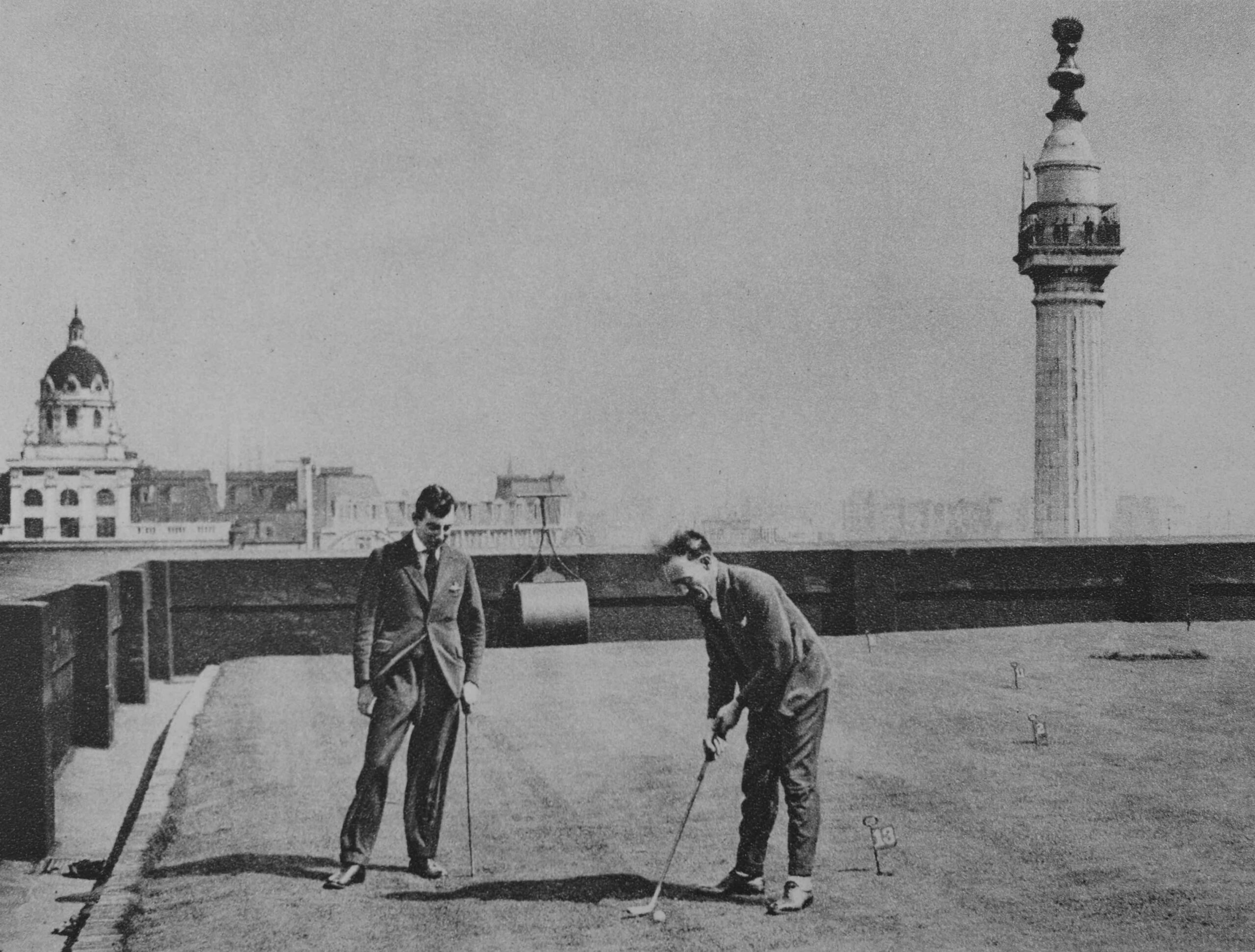

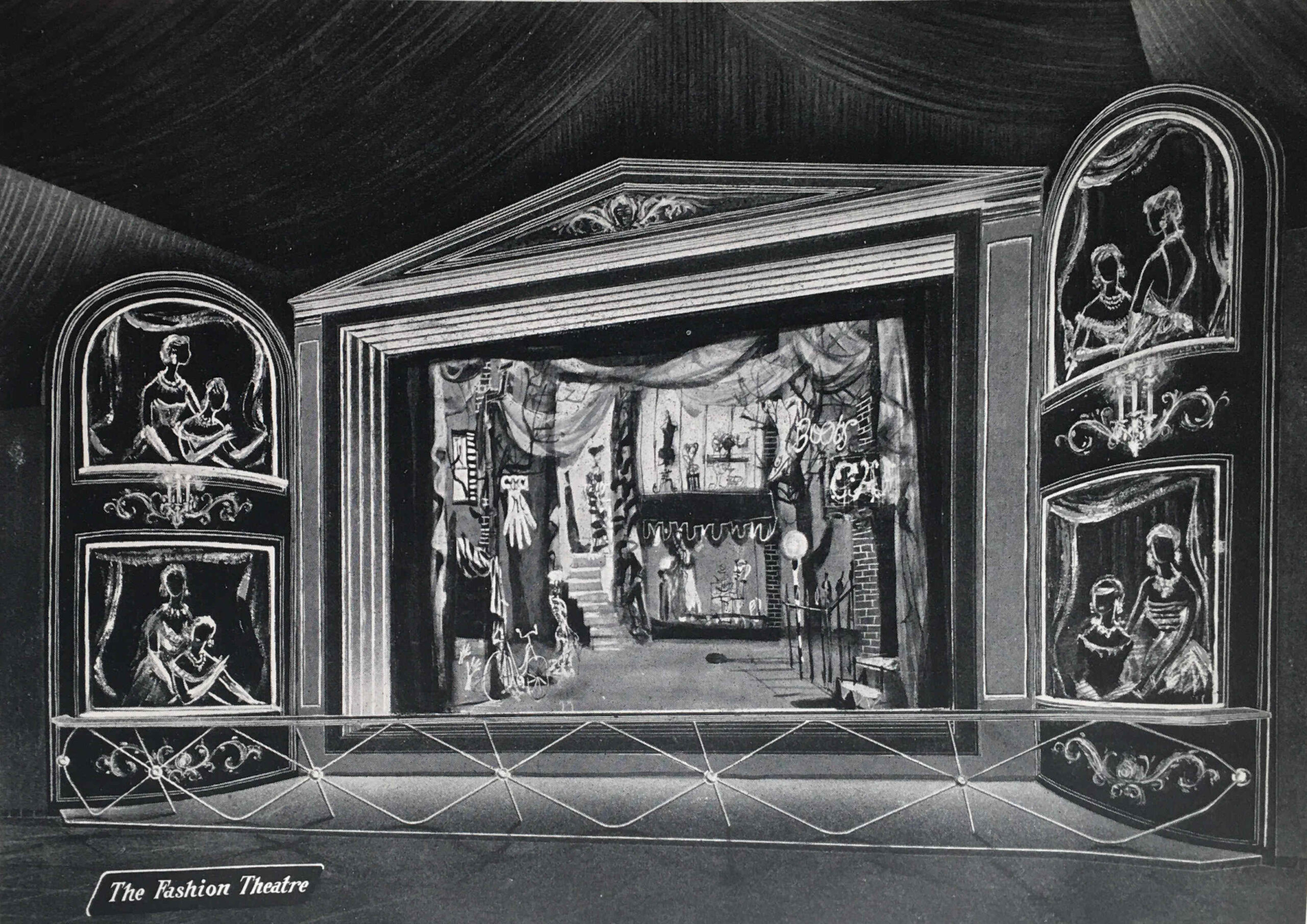

We then come to the “People at Play” section, which is illustrated with “The Fashion Theatre”:

The People at Play section included displays on:

- Outdoor Sports and Games

- Hobbies (Amateur Photography, Amateur Radio, Painting and Home Cinematography)

- Leisure Wear (which was displayed by “actress mannequins” in a continuous performance in the Theatre of Fashion)

- The Rolling English Countryside (walking, rambling, mountaineering, cycling , rowing and canoeing)

- Indoor Sports and Games

A look at the list above might imply that the exhibition was aimed at the affluent middle class, however taking Amateur Photography and Cycling as two example, that is exactly what my father was doing in 1951. He started off with a Leica camera purchased cheaply from a serviceman returning from Germany after the war, and cycled the country with friends after National Service, staying at Youth Hostels, which was a very cheap way of seeing the country.

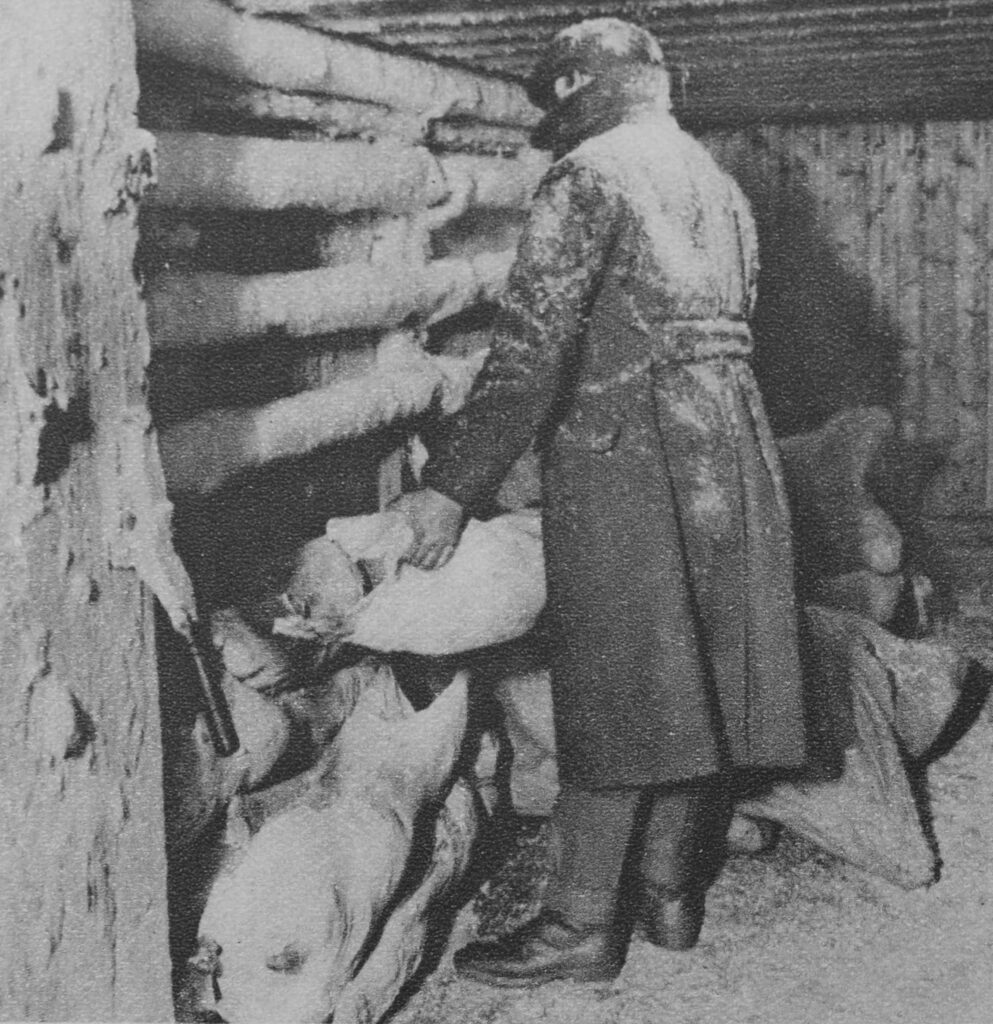

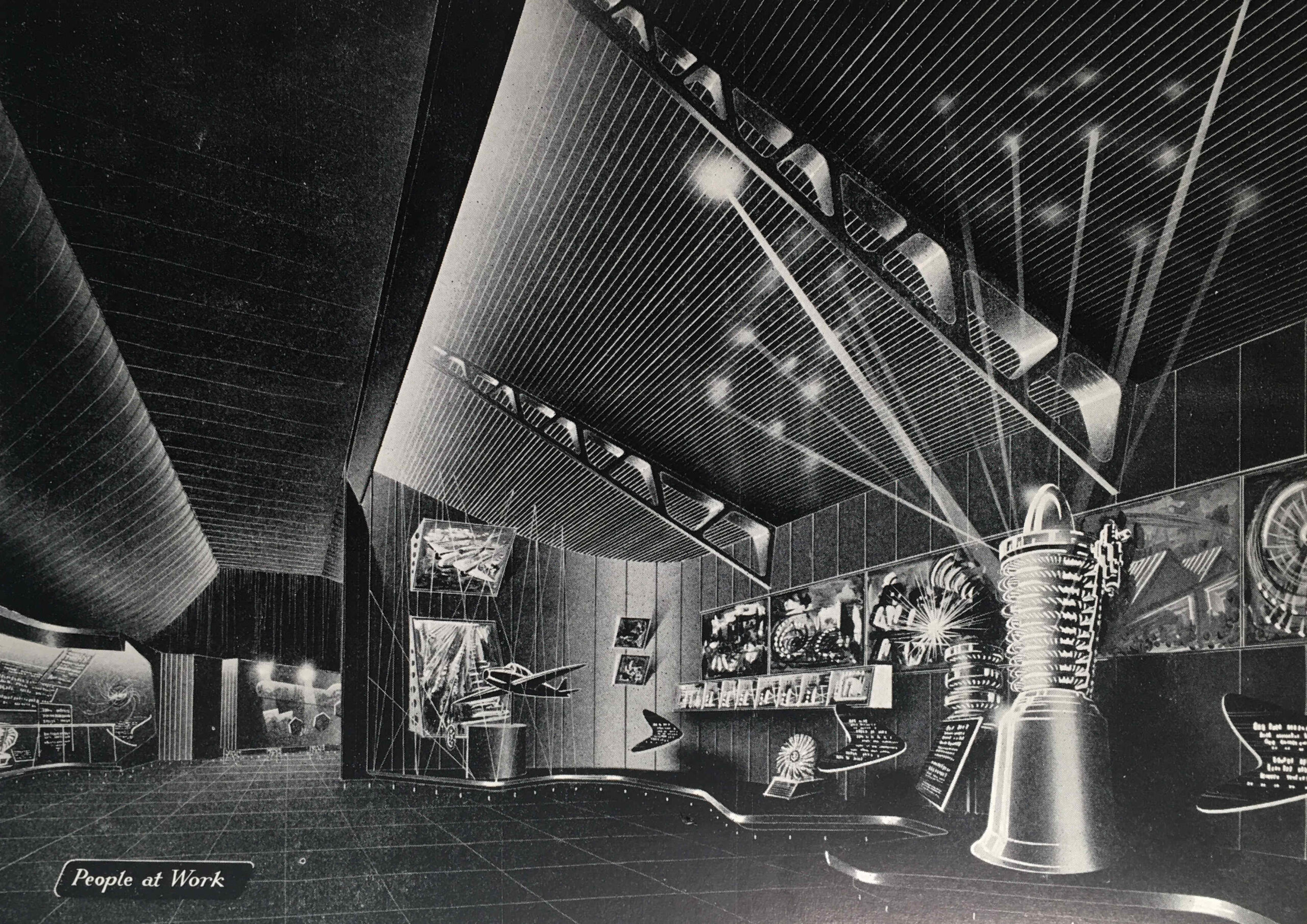

We then come to the “People at Work” section, with an image of the same name:

“Britain’s industrial achievements and engineering skill are renowned throughout the world. We were pioneers and leaders in industrial engineering in the 18th and 19th centuries”, so began the introduction to the “People at Work” section. The guide book featured the jet engine, or the “Whittle Engine” as it was called in the Exhibition Guide after Frank Whittle who was instrumental in the development of the jet engine.

The guide mentions John Barber who had taken out a patent for what would become a gas turbine, the core of a jet engine, as early as 1791.

Barber’s designs were very much in advance of their time, and manufacturing technology was not at the stage where the designs could be turned into a working gas turbine.

In a perfect example of what ever you think the future will be, it will almost certainly be different, in the section on People at Work, there are some paragraphs under the heading “The Future”.

The guide explains that the future of electricity and energy production is with home supplies of coal and peat, and that cheap supplies of these, rather than the expensive oils currently being burned would help power the future.

No understanding in 1951 of the impact of burning large amounts of fossil fuels, and digging up large amounts of peat.

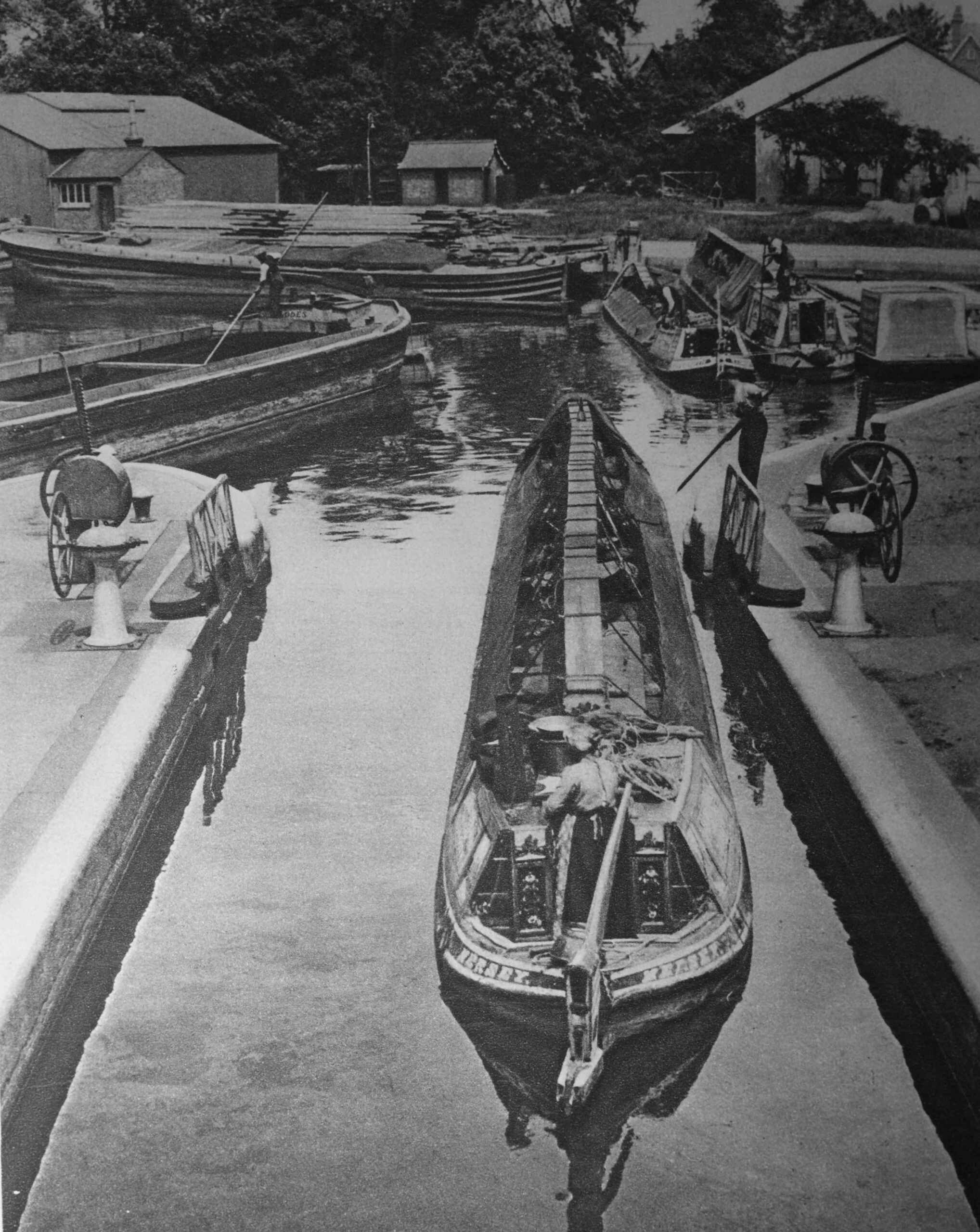

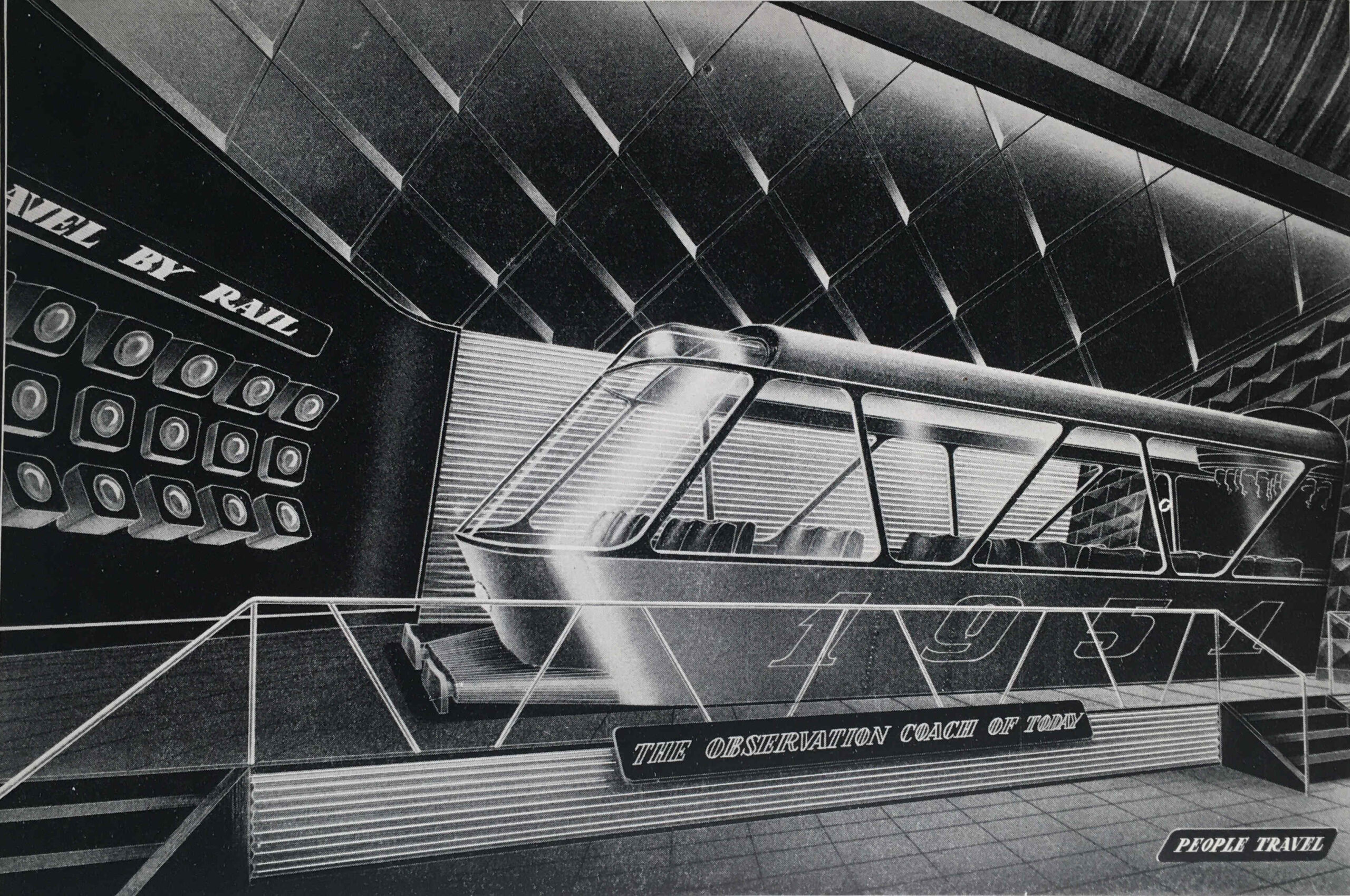

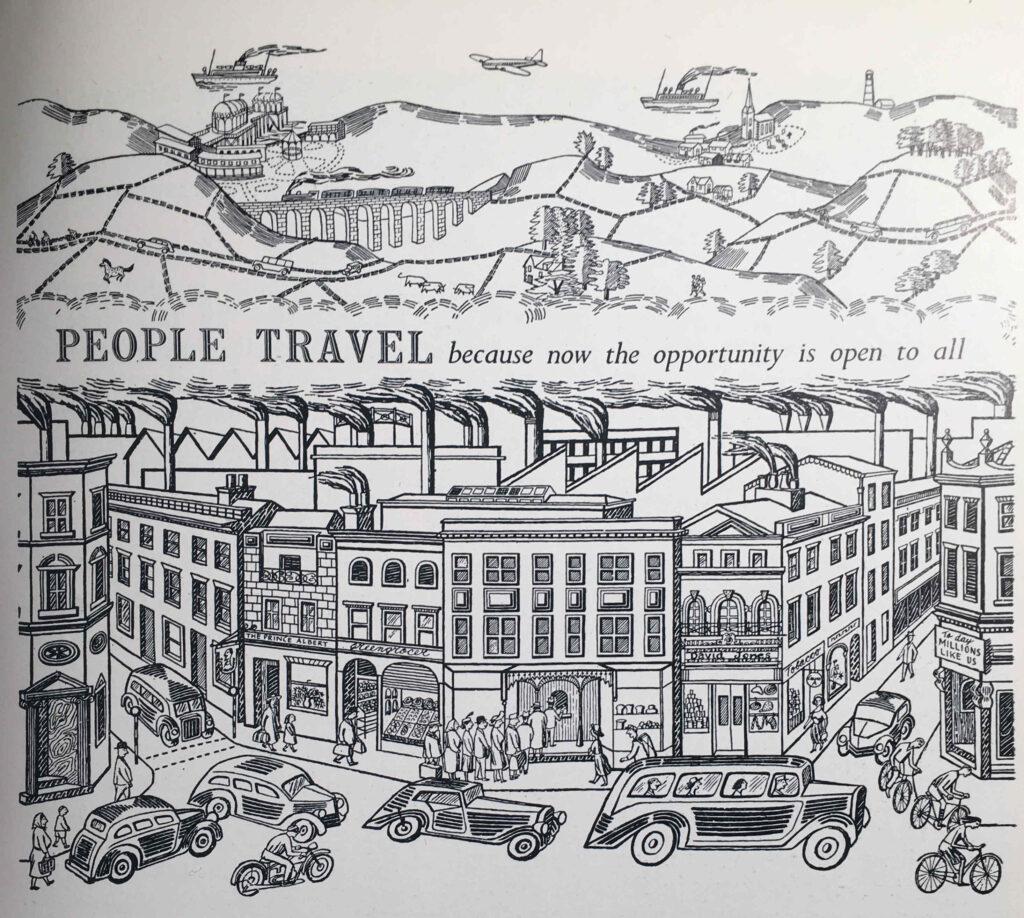

The next section of the exhibition is “People Travel”, with an illustration of the same name:

The guide compares the arduous methods of travel at the time of the 1851 Great Exhibition, with the travel opportunities one hundred years later in 1951, with air travel and the car providing the means to explore the country and the wider world – “the private car has added a new degree of freedom to the mode of life of many people in all countries”.

To show some of the accessories that went with the freedom of travel provided by the car, the exhibition included:

- Picnic Basket “Fieldfare”: G.W. Scott & Sons Ltd, 4-10 Tower Street, London W.C.2

- Twin cup vacuum flask. British Vacuum Flask Co. Ltd. Lissenden Works, Gordon House, London, N.W.5

- Coffee cups and saucers, acrylic. S.C. Errington (Hanwell) ltd, 132a Uxbridge Road, London W.7

- Plastic sandwich box, Marris’s Ltd, 16 Cumberland Street, Birmingham

So the opportunity in the summer of 1951, if you had a car, was a drive out into the countryside, where you could stop and have lunch from your plastic sandwich box, drink coffee from acrylic coffee cups and saucers kept warm in the vacuum flask, all stored in your Fieldfare picnic basket from Tower Street.

“PEOPLE TRAVEL because now the opportunity is open to all”:

The logistics of the travelling exhibition were impressive. It covered an area of 35,000 square feet, and was the world’s biggest transportable, covered Exhibition ever to be constructed.

It needed to be assembled and disassembled quickly due to the tight time schedule of openings and closings in the four different cities.

The exhibits were designed for quick and easy assembly, and to allow for differences between the sites, such as different floor levels, the exhibition structures were on adjustable footings. All exhibits were also completely wired for connecting up at each site.

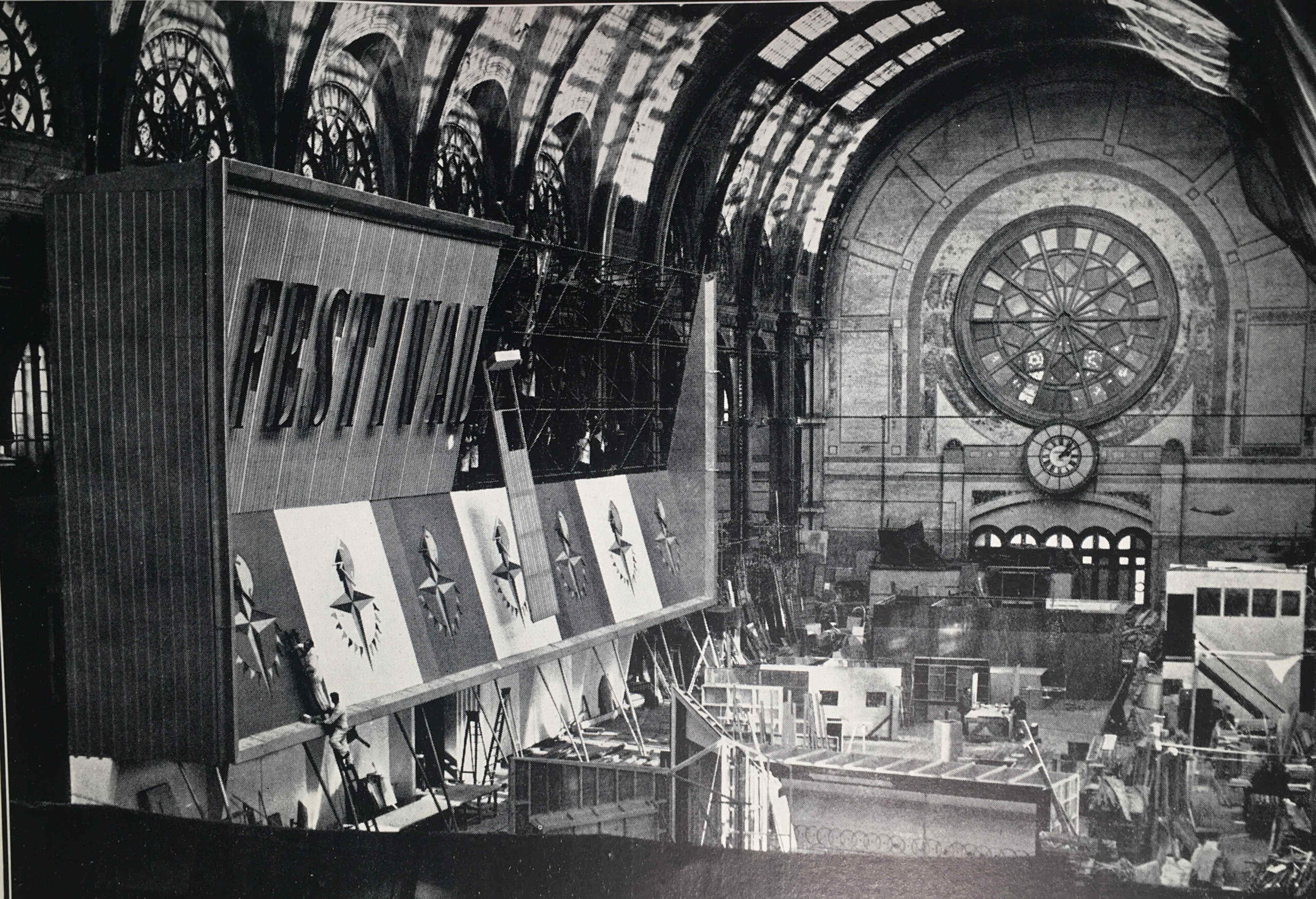

The guide includes a photo of the Exhibition Façade under construction, and I am sure that is the main hall of Alexandra Palace:

Alexandra Palace makes sense as it would have provided a large area for construction of all the exhibits, and the contractors responsible were the City Display Organisation, London.

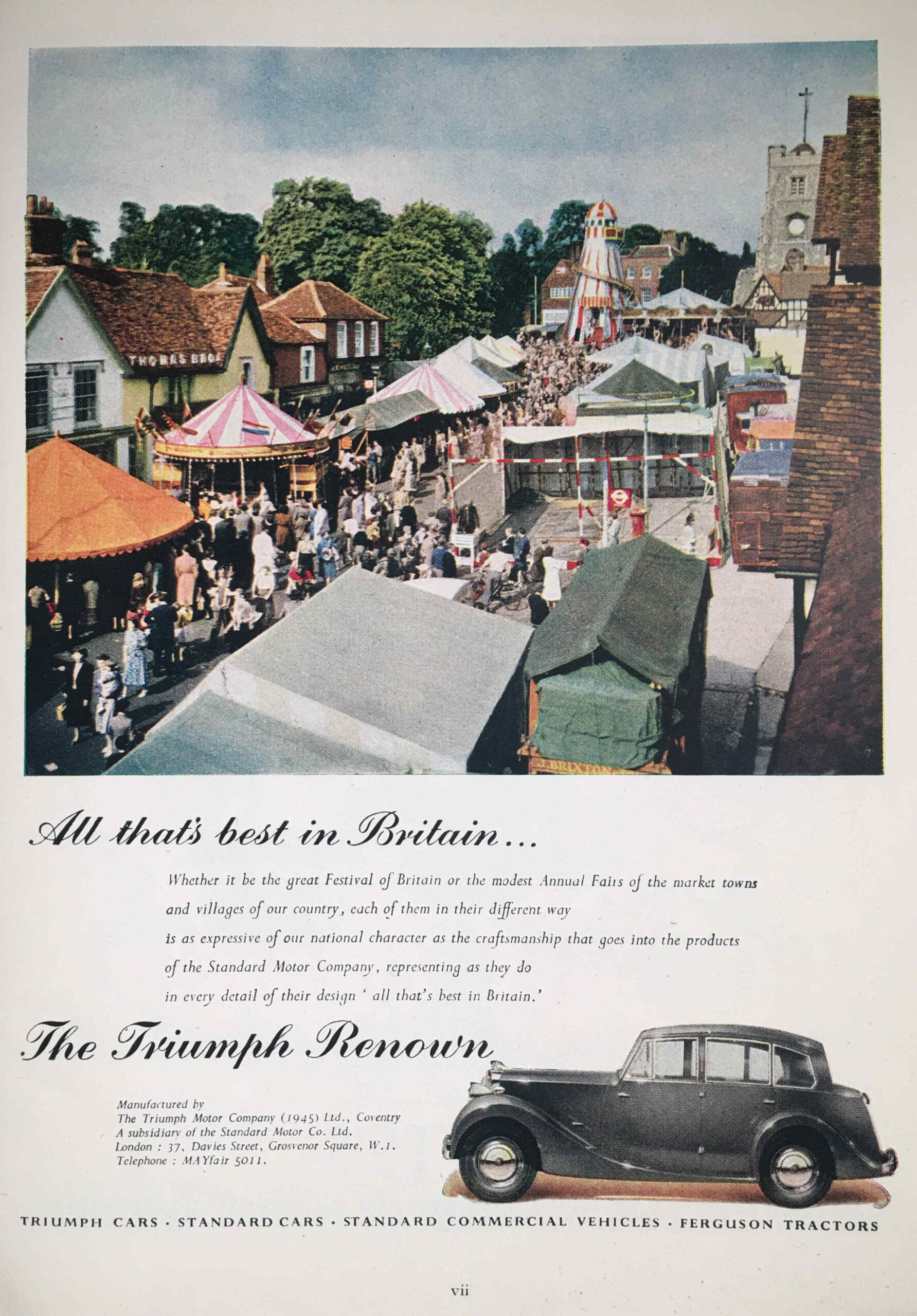

As with all the Festival of Britain Guide Books, the one for the Travelling Exhibition included a large number of adverts, many in colour, and they feature a range of British industrial enterprises, the vast majority of which have all disappeared in the years since the 1951 festival.

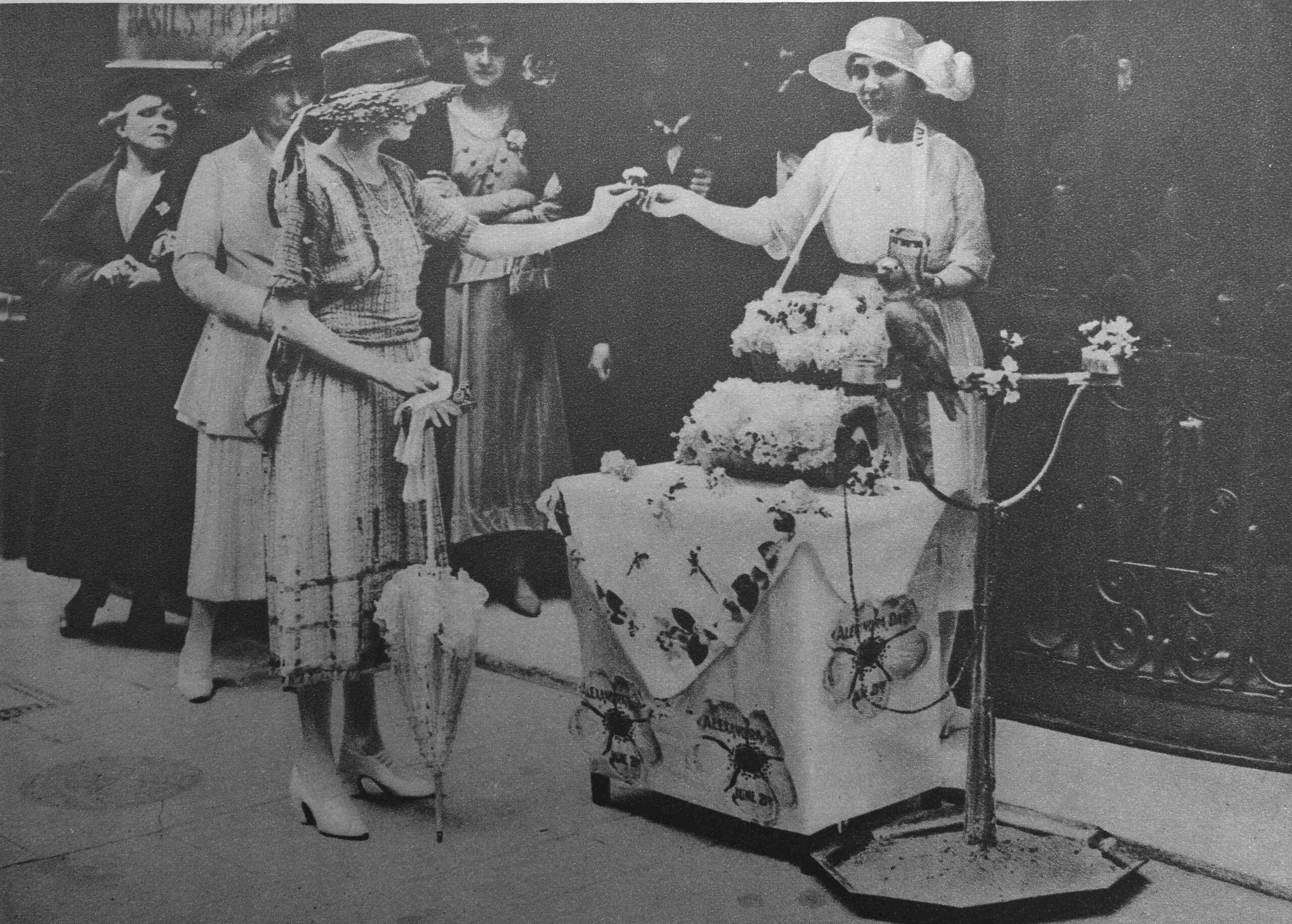

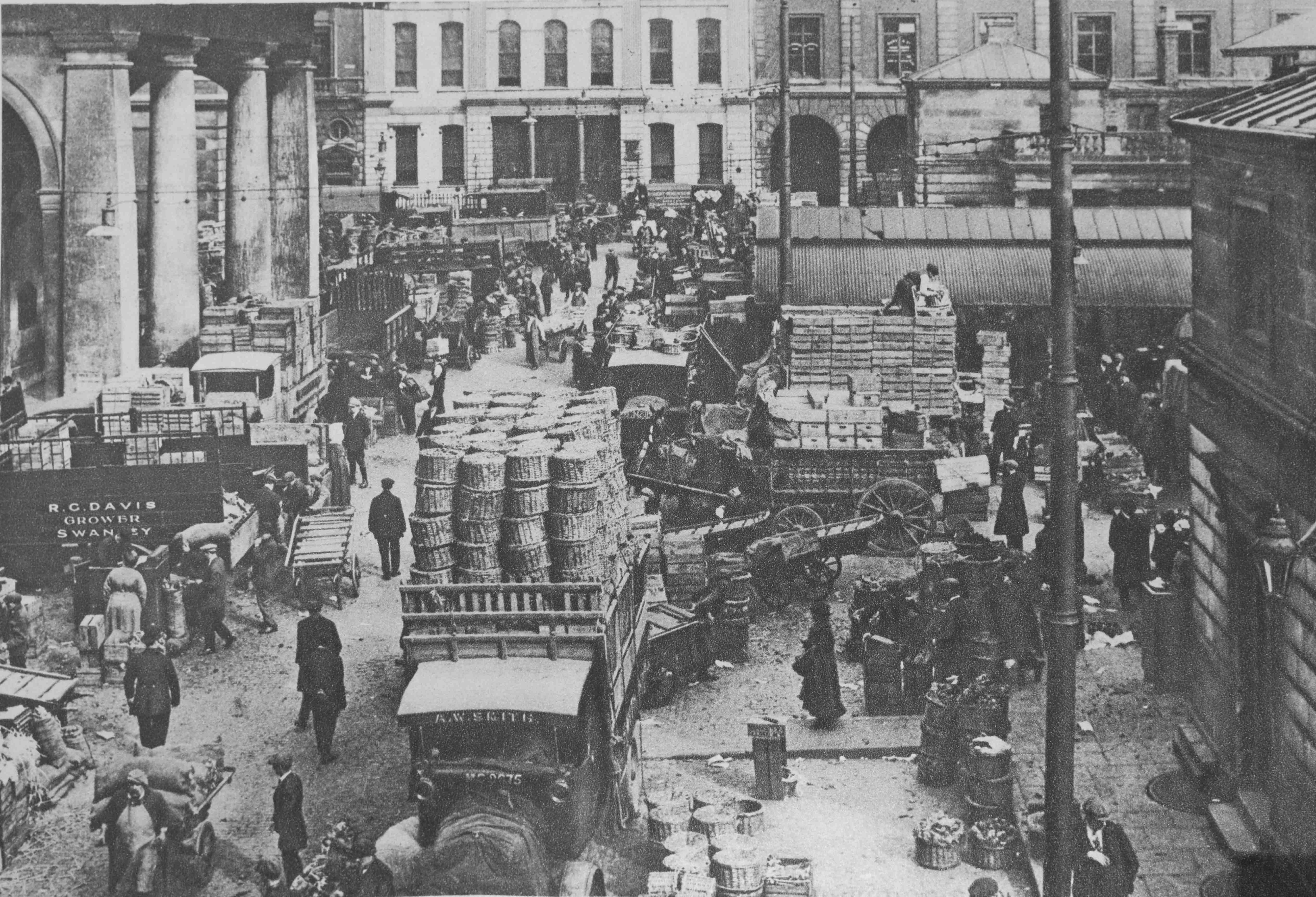

In the Triumph Renown, manufactured by the Triumph Motor Company, you could get out and visit places and events such as displayed in the following photo:

I think that is a location in outer London, as in the photo we can see the following:

Before Lego, there was Minibrix:

Minibrix were manufactured by the Minibrix Rubber Company, a subsidiary of the I.T.S. Rubber Company of Petersfield in Hampshire. Production started in the late 1920s.

The bricks were made out of solid rubber, and were therefore rather heavy compared to the plastic bricks that Lego would later introduce.

Competition from Lego, who used plastic for their bricks, which was cheaper to produce, and allowed a much wider range of models to be built, meant that Minibrix could not compete, and Minibrix ended production in 1976.

The fate of Minibrix sums up much of the industries and businesses featured in the Festival of Britain, with the majority disappearing in the next 40 years.

One that does still thrive is Rolls-Royce, who continue production of the jet engine in Derby.

I still have a couple of Festival of Britain Guide Books to find, but if you would like to read some of my other posts on the festival, you can find them at the following links:

- The Festival of Britain and the Atomic Bomb (the Festival Ship Campania)

- The Festival Of Britain Pleasure Gardens – Battersea Park

- The Festival Of Britain – Maps, Football, Guidebooks. Science And Abram Games

- A Walk Round The Festival Of Britain – The Downstream Circuit

- A Walk Round The Festival Of Britain – The Upstream Circuit

- The Lansbury Exhibition Of Architecture