The Queen’s London was published in 1896 and described as “A pictorial and descriptive record of the Streets, Buildings, Parks and Scenery of the Great Metropolis in the Fifty-Ninth Year of the reign of Her Majesty Queen Victoria”.

The book is a fascinating snapshot of London at the end of the 19th century and the last years of Victoria’s reign. It was a century that had seen considerable change across the city. Railways, Underground Trains, Sewers, new streets such as Queen Victoria Street, new cultural institutions, dramatic growth of the London Docks, industry, the emergence of a middle class.

It was these themes that the book portrayed, the Great Metropolis at the heart of an Empire on which the sun never set.

What the book did not show was the poverty, the impact of industrialisation, crowded and insanitary housing which was still to be found across large areas of the city.

The photos can look rather strange, almost a combination of photography and drawing. Some of the people in some of the photos look as if they have been added. This may all be down to the photographic and printing processes of the time.

The photos in the book change between photos that are instantly recognisable today (take away the horse and carts and replace by cars and the scene is almost the same). to photos of places which have changed beyond all recognition.

I was planning to do a then and now sequence of photos, but the current lock down has stopped that, although I have included a couple of examples. Hopefully something to revisit.

The photos and their supporting text also help understand how well known locations have developed, one such example is:

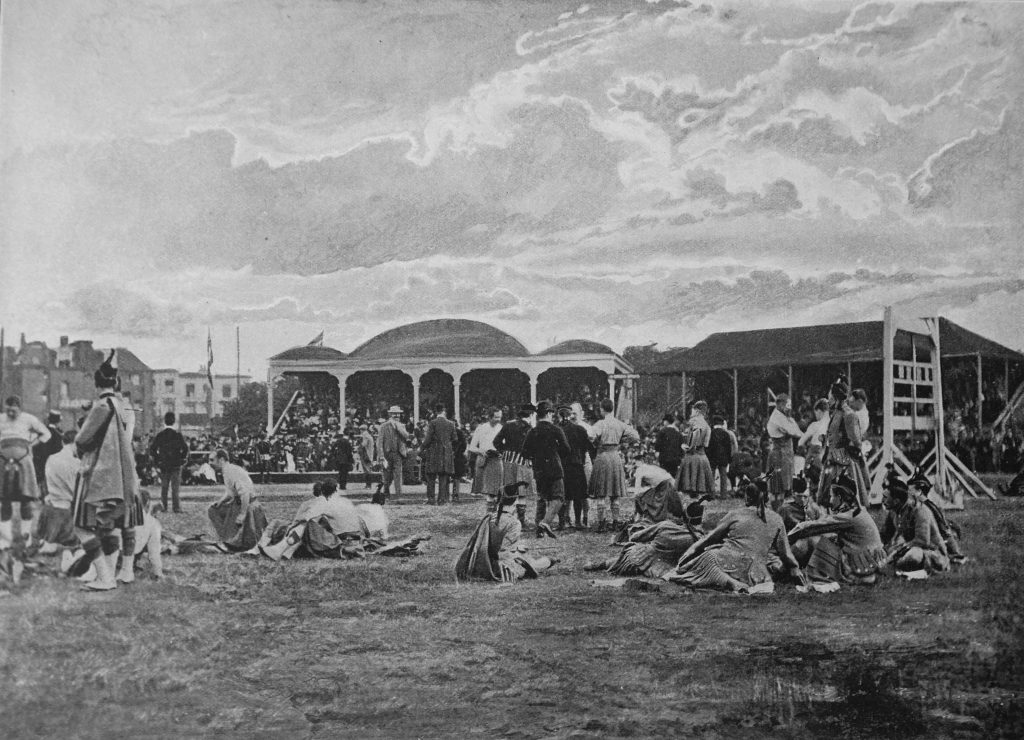

The Scottish Gathering at Stamford Bridge (1895)

The text with the photo states “Stamford Bridge, on the Fulham Road is the best known athletic ground in the Metropolis, being the headquarters of the London Athletic Club and the scene of the amateur championship competitions whenever they take place in London. The annual Scottish Gathering is one of the most popular fixtures held here”.

This is the same Stamford Bridge that 10 years later in 1905 would become the home for the newly formed Chelsea Football Club. Additional land was purchased around the ground, but the home of the London Athletic Club since 1877 would become the core of Chelsea’s ground. Another London ground featured in the book was:

Football At The Crystal Palace

The text states “Football has become so popular with all classes of the community that the Crystal Palace authorities were well advised in laying out a part of the fine gardens at Sydenham as a football ground. The lake was filled in for this purpose; and from the spectators point of view, there is no finer ground in the country. Our picture shows in progress the final tie for the Football Association Cup in the 1894-5 season. This match, the most exciting of the year under Association rules, was won by Aston Villa, who defeated West Bromwich Albion by a goal to nothing”.

Although Crystal Palace would not become a professional club for another 10 years (in 1905), Crystal Palace as an amateur team had been formed a couple of decades earlier to enable the cricketers of the Crystal Palace Company to play sport during the winter.

What I cannot work out with the photo is why the people in the immediate foreground appear to be standing on some form of terraced stand, so far back, with a grass space between them and the pitch.

St. Pancras Station: The Exterior

The railways, one of the great 19th century changes to London, here show by St. Pancras described as “this splendid Gothic pile, designed by Sir Gilbert Scott, is ornate to a degree seldom seen in such structures, and is of a rich red, well calculated to defy the begriming effects of London’s atmosphere. The front, facing the Euston Road, constitutes the Hotel. The clock tower is the finest feature of the facade. On the right of the picture is shown the entrance to King’s Cross railway station, the terminus of the Great Northern Railway, with part of the station hotel”.

The interior was also featured:

St. Pancras Station: The Interior

“Without question, the London terminus of the Midland Railway Company can challenge favourable comparison with any other station in the world. The station itself is not so extensive as the Great Eastern terminus, in Liverpool Street, but it is said to have the largest roof, supported by a single pillar, in existence. This triumph of construction was designed by Mr. Barlow”.

It was not just railway stations that had wonderful 19th century arched roofs. Another was at the Agricultural Hall, Islington:

The Cattle Show, 1895

“Many Londoners never realise that Christmas is at hand until the Smithfield Club’s annual show of fat beasts is opened at the Agricultural Hall, Islington. Our view was taken after judging was completed, and on the notices above the exhibits are recorded the awards won, the weights, and the names of the butchers who had purchased the beasts for Christmas beef”.

Whilst the photo of the Agricultural Hall is clearly a photo, with the following example, it is not clear whether elements of the overall scene may have been drawn, or somehow added to the photo.

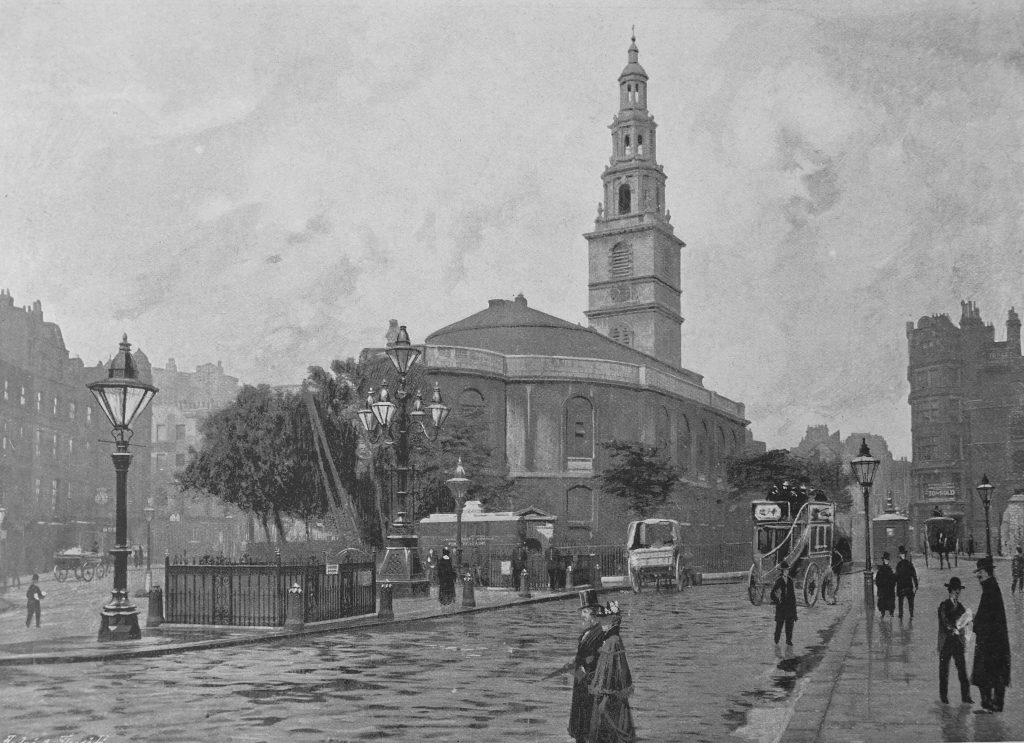

St. Clement Danes

Whilst the church is obviously a photo, I am not sure about the people. Look close and they just do not look right. Possibly the way the photo was printed, real people may have been enhanced in the process, or they may have been added.

The text states that “St. Clement Danes’ occupies a commanding position near the eastern end of the Strand. It was built in 1682, under the superintendence of Wren, the tower, however, being added in 1719; and it was restored in 1839. The tower is 115 feet high”.

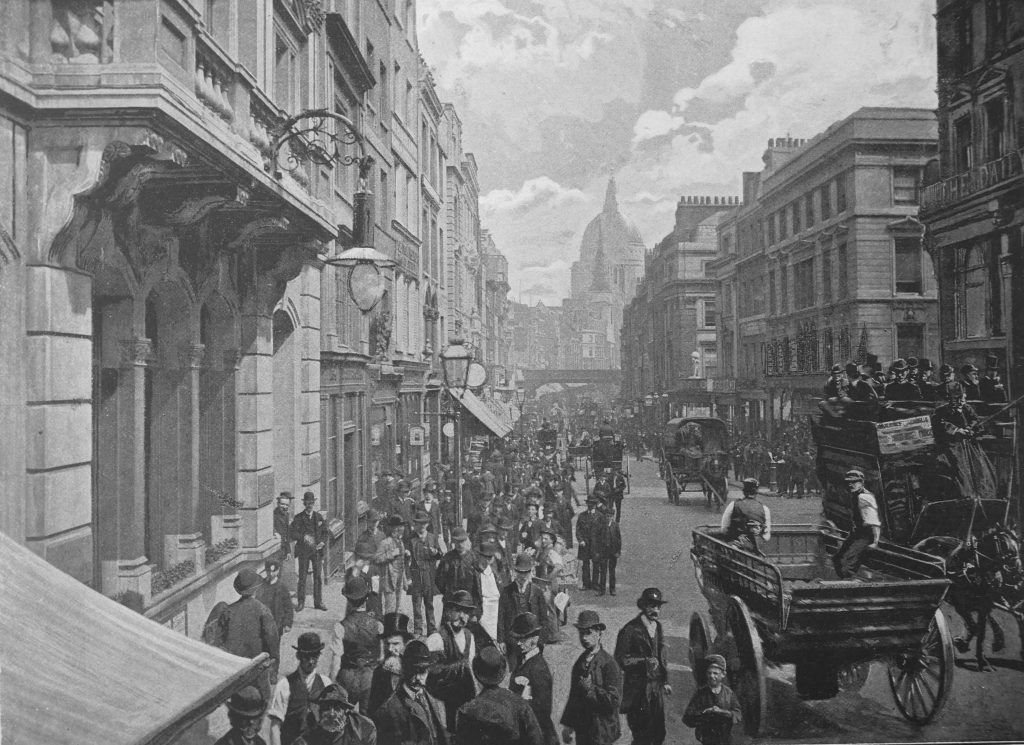

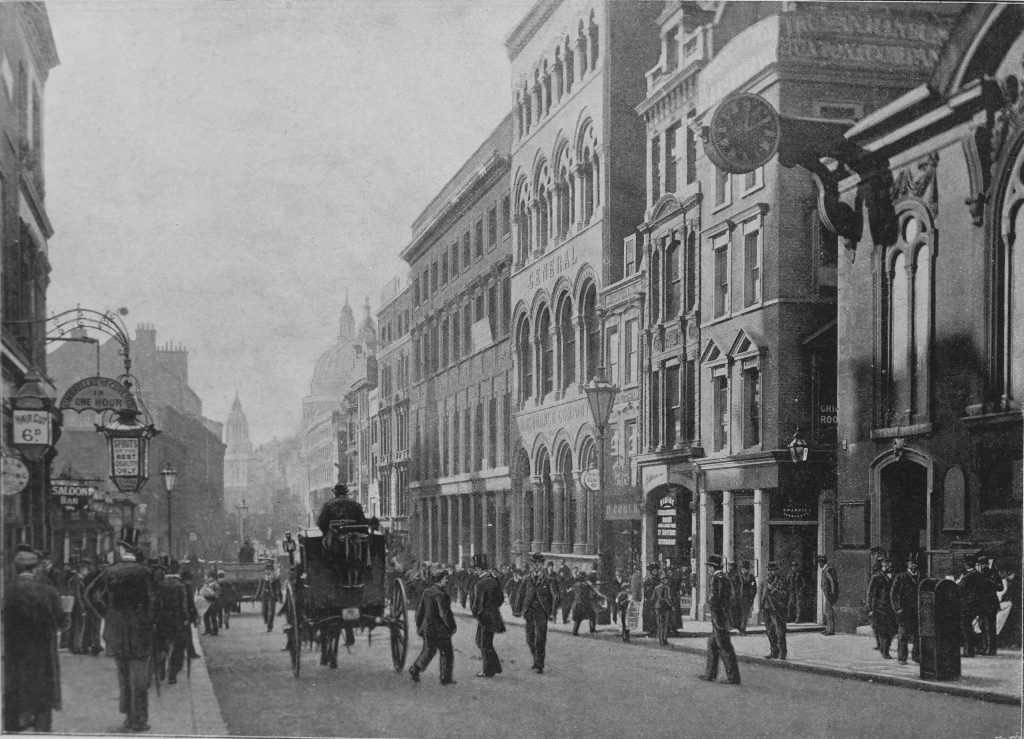

Fleet Street, Looking East

“Our view shows this narrow, though main, thoroughfare, the headquarters of London journalism, in a characteristic state of bustle. On the left is the resplendent office of the Daily Telegraph, marked by an electric lamp, on the other side is the advertisement office of the Daily Chronicle. The figure of Atlas a little further on calls attention to the office of the World, and in the same court, which leads to St. Bride’s church, Mr Punch is at home”.

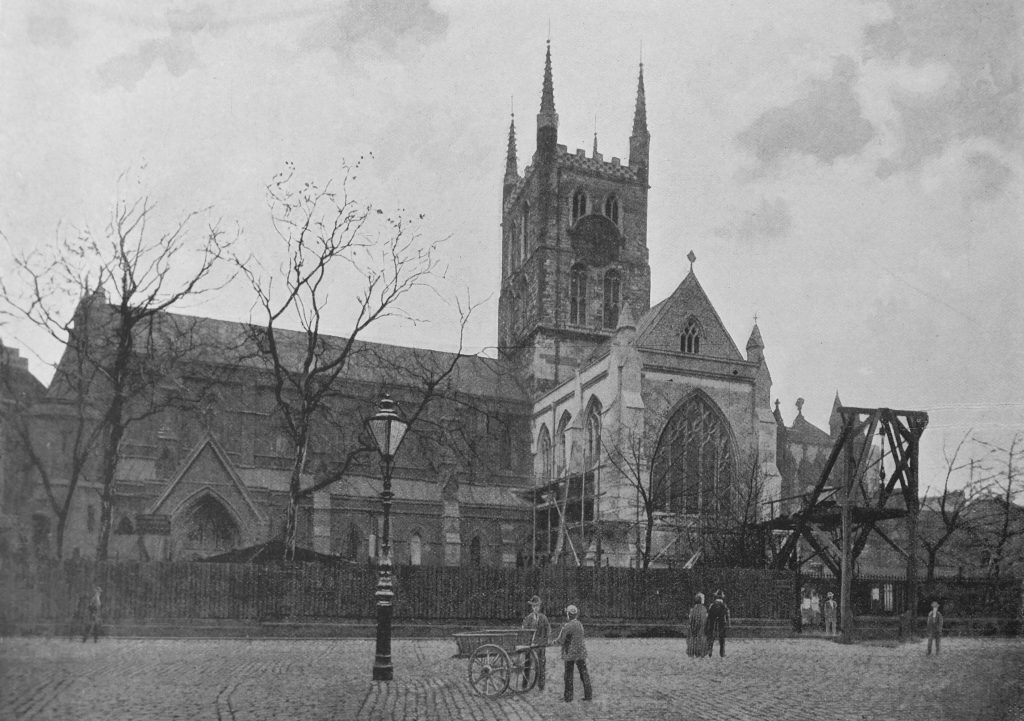

St. Saviour’s, Southwark

St. Saviour’s, Southwark became Southwark Cathedral in 1905, up till then the church had been known as St. Saviour’s, and much earlier, before the reformation, as the Priory Church of St Mary Overy.

I have no idea what the strange wooden contraption is at the front right of the photo. It may have been part of restoration work on the building, which happened a number of times during the 19th century. In 1840 when the nave was rebuilt, with a later rebuild of the same nave as the earlier had been to such a poor standard.

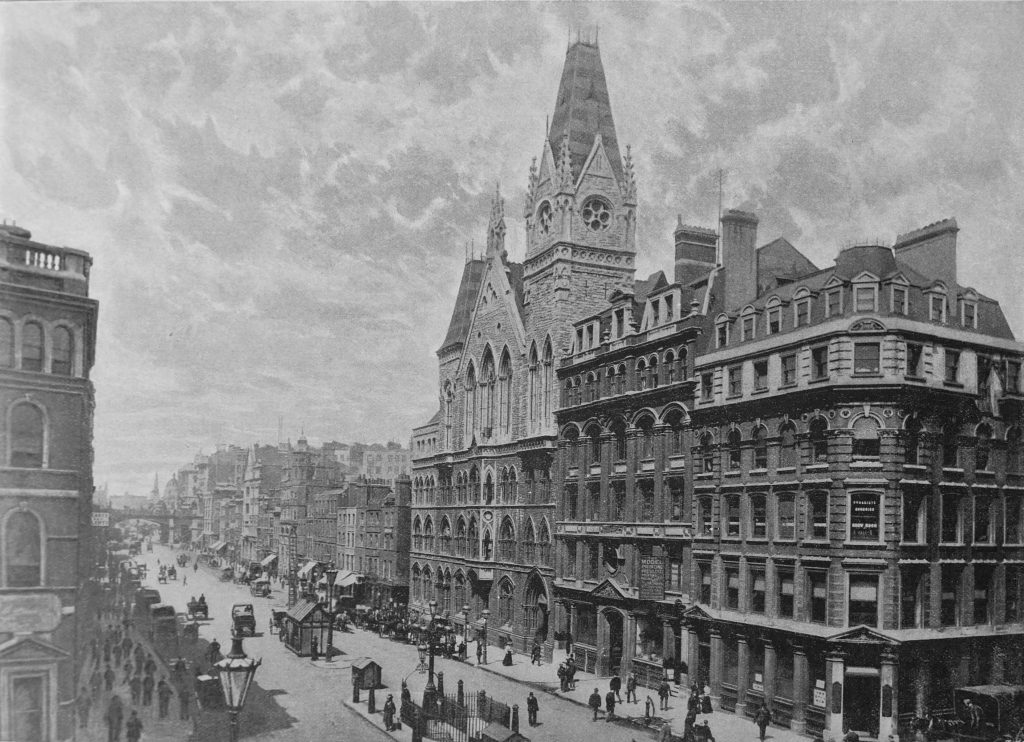

The Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street

The Memorial Hall (the building in the centre of the photo with the tower), was built by the Congregationalists “in memory of the two thousand clergymen who, for their non-subscription to the Act of Uniformity, were deprived of their livings in 1662″.

The Act of Uniformity restored the Anglican Church and the two thousand clergymen refers to those with a Puritan leaning who could not support the restored church.

The building contained a hall capable of holding 1,500 people, a library and offices. The building occupied the site of the Fleet Prison and was demolished in 1968.

Another lost building is:

Columbia Market

“In the belief that one of the crying needs of London was ampler market provision, the philanthropic Baroness Burdett-Coutts had Columbia Market built in Bethnal Green, in the Columbia Road, off the Hackney Road, near Shoreditch Church”.

It was intended that the market would sell meat, fish and vegetables, however the market was never really a success. The central market was enclosed by residential buildings, originally named the Georgina Gardens, but were more often referred to as the Baroness Burdett-Coutts Buildings. The building was later taken over the by City of London and demolished in the 1950s.

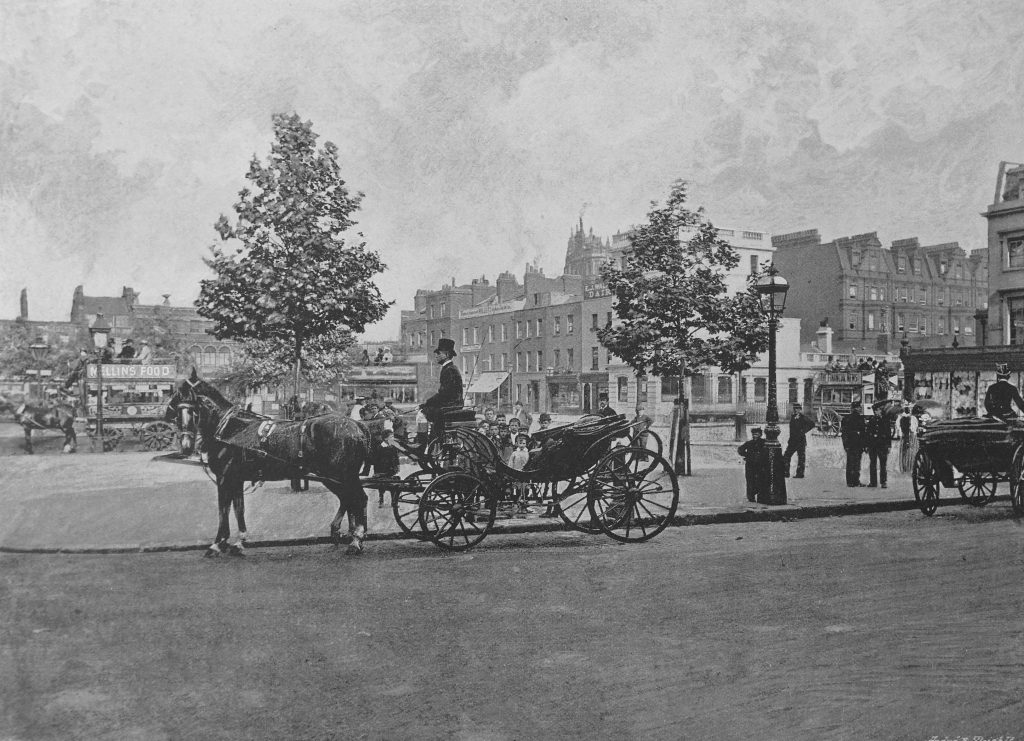

Sloane Square

“Sloane Square, as well as other places in the neighbourhood, owes its name to Sir Hans Sloane, the founder of the British Museum who purchased the Manor of Chelsea early in the last century”.

Hampstead Heath: The Flagstaff With Approach To “Jack Straw’s Castle”

“That part of ever-attractive Hampstead Heath marked by the Flagstaff is one of the highest and breeziest points. Our view embraces part of the pond dear to dogs and horses; and ever attractive to children, and in winter to skaters of all ages”.

The view of the Flagstaff is one of the photos where people in the scene are obviously photographed, rather than added or enhanced as in a number of photos. Fascinating to see these late 19th century Londoners on the streets of the city.

Ostrich Feathers At Cutler Street Warehouses

The Cutler Street Warehouses in Houndsditch were owned by the London and St. Katherine’s Dock Company. Covering four acres and with a floor space of 630,000 feet, they provided a vast amount of storage space for goods of all kinds.

Ostrich feathers were classed as of “great value” and are shown in the photo being stored in the warehouses. The caption to the photo adds that “Such feathers such as those shown above may well have a fascination for all womankind, from a duchess to a coster’s sweetheart”.

Wentworth Street On Sunday Morning

“Wentworth Street is off Middlesex Street, once known as Petticoat Lone – and appropriately so, for it was the headquarters of the old cloth trade – not far from Aldgate Railway Station. In Wentworth Street, any Sunday morning, may be seen such a spectacle as is portrayed in our picture”.

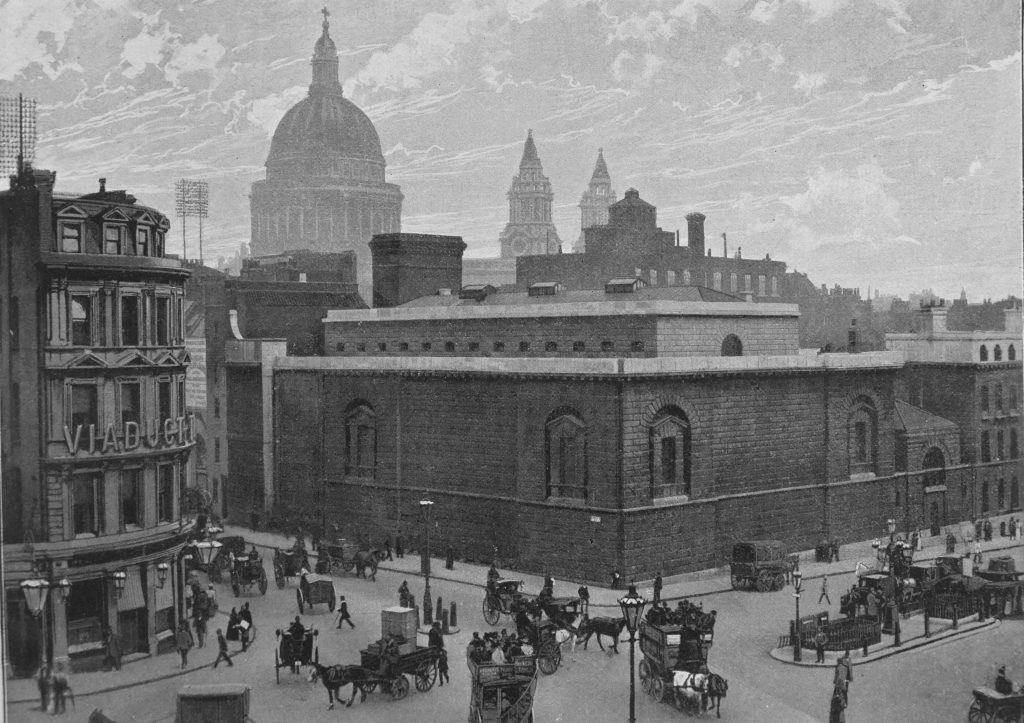

Newgate Prison

“At the corner of Newgate Street and of the Old Bailey is the gloomy granite building which was once the chief prison in London, but is now only used for prisoners awaiting trial at the Central Criminal Court, and for those condemned to death”.

Although Newgate Prison was demolished many years ago, the pub on the corner, the Viaduct Tavern, is still there and looking over a very changed view.

Olympia

The Victorians made good use of the materials and ability to construct large spaces, covered by an arched roof. Railway stations, the Agricultural Hall in islington, and in the above photo, Olympia, providing, until Earl’s Court was built, the largest stage in London.

Olympia could seat ten thousand spectators and hosted shows such as Barnum’s Show, the Paris Hippodrome, the Spectacle of Nero, Venice in London, the Sporting and Military Show.

The text adds that an innovation at Olympia was the ability to reserve seats in all parts of the building.

The Strand, With St. Mary’s Church, Looking East

St Mary-le-Strand was designed by James Gibbs, the first of the so called fifty churches planned during the reign of Queen Anne. It was substantially completed in 1717. Today, the church sits on an island with the Strand passing on both sides. When the photo was taken, the Strand ran to the right, and the narrow street to the left of the street was Holywell Street, which would later be demolished to allow for widening of the Strand.

Old Weavers’ Houses At Bethnal Green

The photo is of Florida Street, Bethnal Green, a street that still exists but looks very different with all the old weavers houses demolished. Just think how much they would be worth now if they had survived.

View From St. Paul’s Looking South-West

The view of an industrial city, where chimneys competed with church towers. The shed of Blackfriars station of the London, Chatham and Dover railway, with the railway bridge on the left long with Blackfriars Bridge. Waterloo Bridge in the distance.

I took a photo of the same scene a couple of years ago. The station is now hidden, and apart from the bridges, the only features which remain are the Houses of Parliament in the distance and in the foreground, the tower of St Andrew by the Wardrobe.

View from St. Paul’s Looking North-West

Paternoster Row is in the foreground of the above photo, an area that would be obliterated just under 50 years later. The tower of the Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street (earlier photo in the post) is the large building on the left. The church tower to upper right of centre is that of St. Andrew’s Holborn.

The same view today. The tower of St. Andrew’s Holborn is just visible in the upper centre of the photo.

The Old Bailey appears in the “now” photo and not in the 1896 photo, as work on this latest incarnation of the Old Bailey would not be started until 1902, opening in 1907. Even in the first years of the 20th century, the skyline of the city could change very quickly.

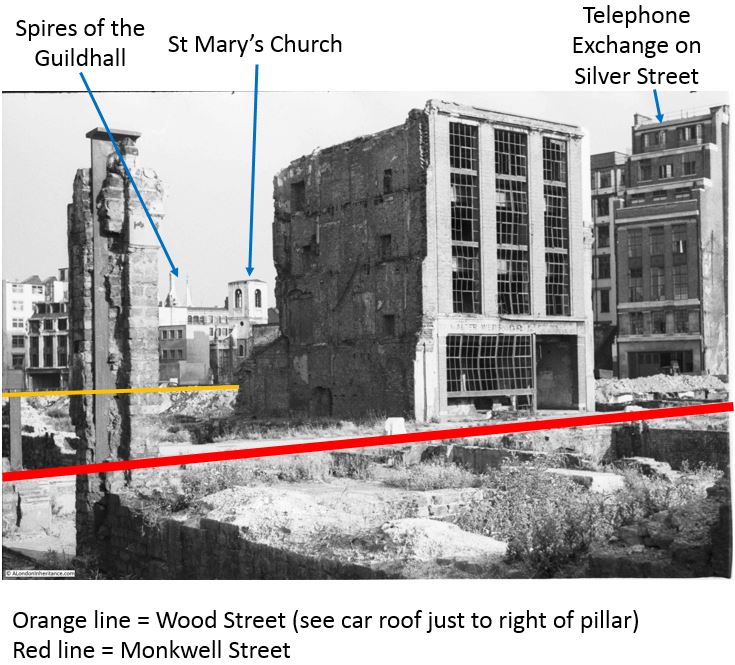

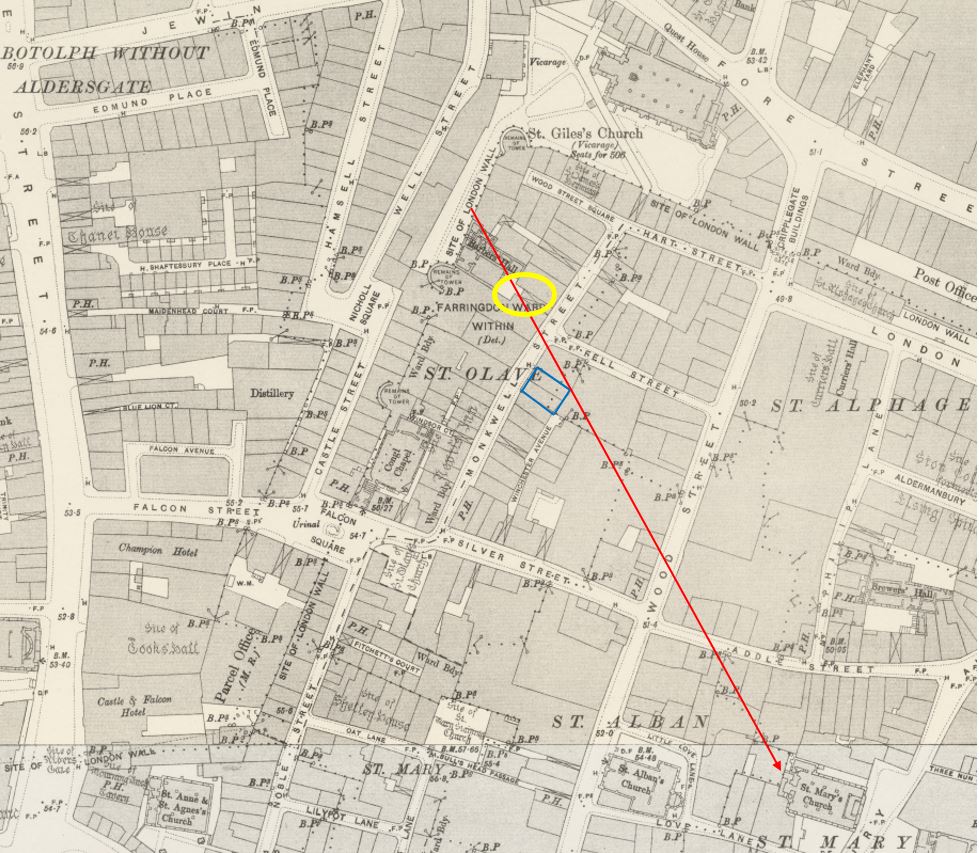

View From St. Paul’s Looking North-East

Again, an area that would see heavy damage almost 50 years later. In the centre of the photo is the distinctive tower of St Giles Cripplegate. In 120 years St Giles Cripplegate would just about remain visible in the same view.

In the above photo, apart from the church, there is just one other building that has remained. On the lower left of the above photo is a building on a street corner – this building can also be seen in the 1896 photo.

I wonder what the Victorian readers of The Queen’s London would have thought if they could have known what London would look like around 120 years later. Comparison photos like this always make me wonder what the same view will look like in another 120 years.

Cannon Street, Looking West

“This view of ever-busy Cannon Street is taken from the rising ground just east of the railway station of the South-Eastern and Metropolitan Companies. The church on the extreme right of the picture is St. Swithin’s with the exterior wall of which is incorporated an old stone, believed to be that from which distances on the British roads were measured during the Roman occupation”.

St. Swithin’s church is one of those lost during the last war. Badly damaged, the church was not rebuilt. The old stone referred to in the text is the London Stone, which can still be seen in Cannon Street, now located in a new housing.

Interior Of Charing Cross Station

Another of the iron and glass covered buildings of the 19th century, Charing Cross Station was the terminus of the South-Eastern Railway. The station included a Customs House where passengers arriving from the Continent were “examined”.

A London County Council Band In Battersea Park

The London County Council was responsible for many of the “improving” initiatives across London during the later decades of the 19th century. This included the organisation of a number of Council bands, funded by the council. The Queen’s London commented that “The Council’s bands, it must be said, are capitally organised, and no ratepayer with any music in his soul can feel that he does not get his money’s worth”.

The Lord Mayor’s Procession (1895) From Punch Office In Fleet Street

The 9th November 1895, and the new Lord Mayor, Sir Walter Wilkin is on his way to the Law Courts to be sworn in to his new role.

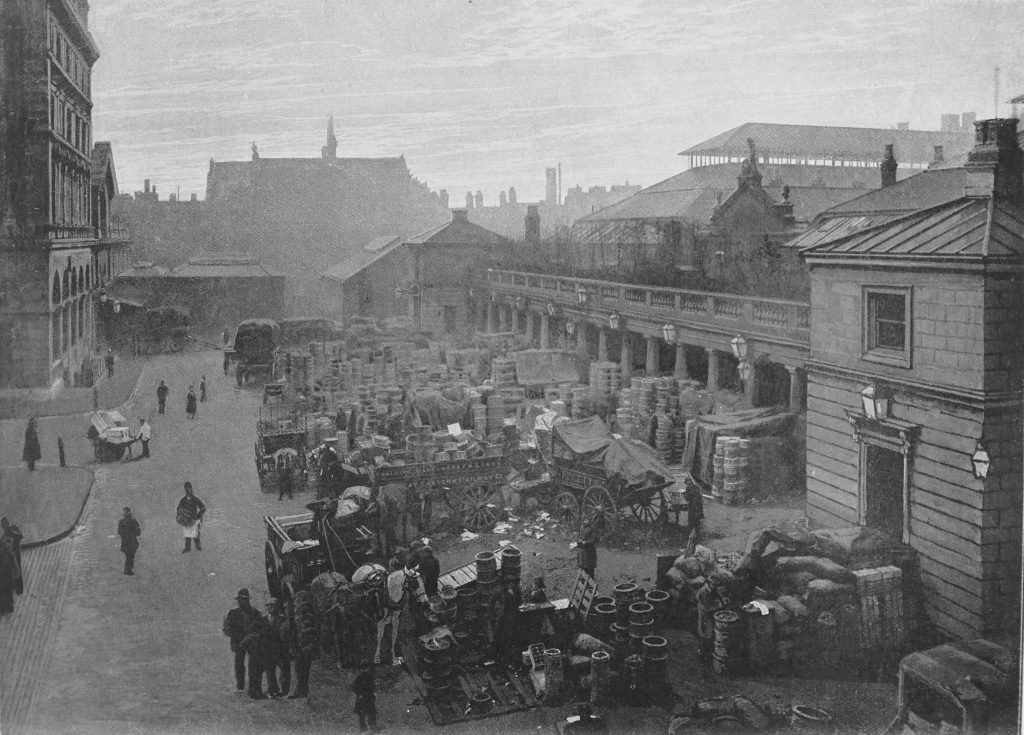

Covent Garden Market

“Covent Garden is, as all the world knows, the chief fruit, vegetable and flower market in London. it stands in a district abounding with the most interesting historic memories, but the present market buildings were only erected in 1831: and although they have been enlarged since then, they are quite inadequate for their purpose. Since the middle of the sixteenth century, Covent Garden has been the extremely profitable property of the Dukes of Bedford”.

The Dukes of Bedford ended their ownership of Covent Garden in 1913 when they sold the building and land. The estate is now owned by the listed company Capital & Counties Properties PLC.

Holborn Viaduct, From Farringdon Street

Holborn Viaduct was opened just 27 years before The Queen’s London was published. Before then, travelers had to pass along the descent of Holborn Hill. The text with the photo gives an indication of the importance of infrastructure within the city during the 19th century as the text remarked that a great deal of the engineering skill of the bridge, was in carrying the gas and water pipes across, without being visible.

The Monument

A photo from the time when the Monument still rose above the surrounding buildings. There is an indication of new services being rolled out across the city, with on the roof of the building to the left of the Monument, a telegraph pole, carrying the wires of the early telegraph / telephone system across the city.

Leicester Square

Leicester Square looking very different to today. The Alhambra Theatre of Varieties is the large building with domes on the roof. The brick building to the right is Archbishop Tenison’s Grammar School.

Euston Station

In the Queen’s London, Euston Station was described as having a “less lofty roof than any other London termini of the great railway lines; but it is the oldest of them all”. The book states that seventy trains go in and out of Euston daily; and that there are three hundred leavers in the station’s signal box.

In an indication of the expected readership of The Queen’s London, the text states that “the station presents a remarkably crowded appearance in August during the two or three days prior to the beginning of the shooting season in Scotland”.

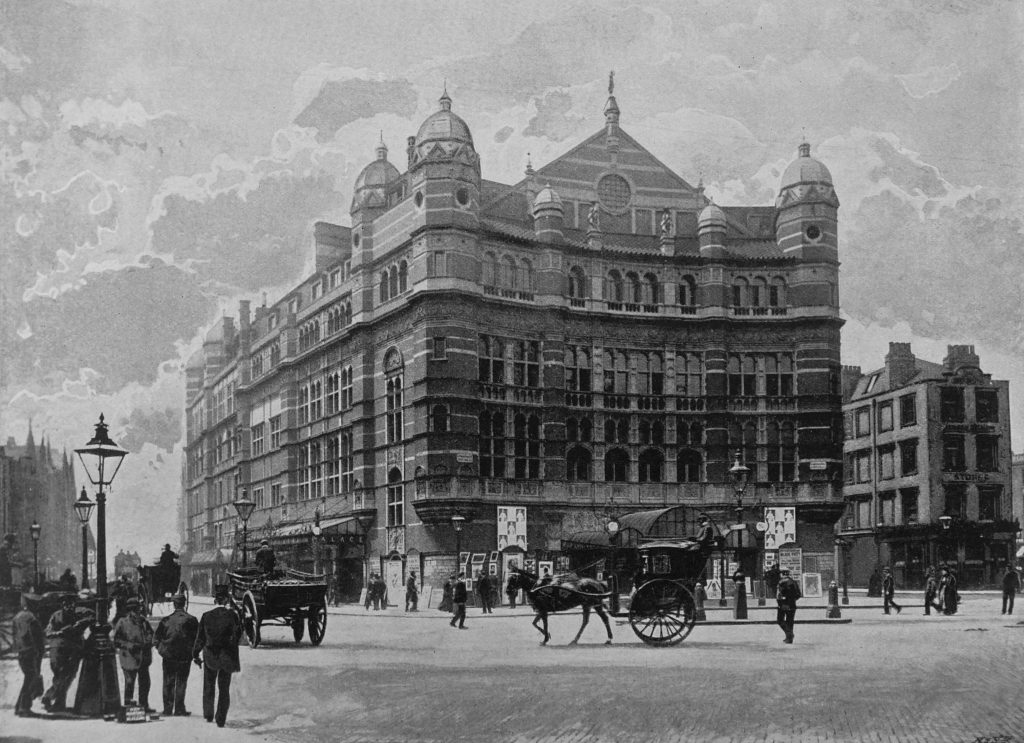

The Palace Theatre

“It is generally admitted the the Palace Theatre is the most beautiful playhouse in London. Regardless of expense it was built for Mr R. D’Oyly Carte by Mr. T.T. Colcutt, the architect of the Imperial Institute, who was fortunate in obtaining such a splendid site as Cambridge Circus. The Royal English Opera House was opened with a great flourish of trumpets, and with the highest hopes on January 31st 1891, Sir Arthur Sullivan’s grand opera Ivanhoe being for the first time produced. But Mr. Carte’s operatic scheme did not gain the support it deserved, and in July of the following year, the name of he house was changed to the Palace Theatre”.

The Palace Theatre a couple of years ago, looking identical to 1896.

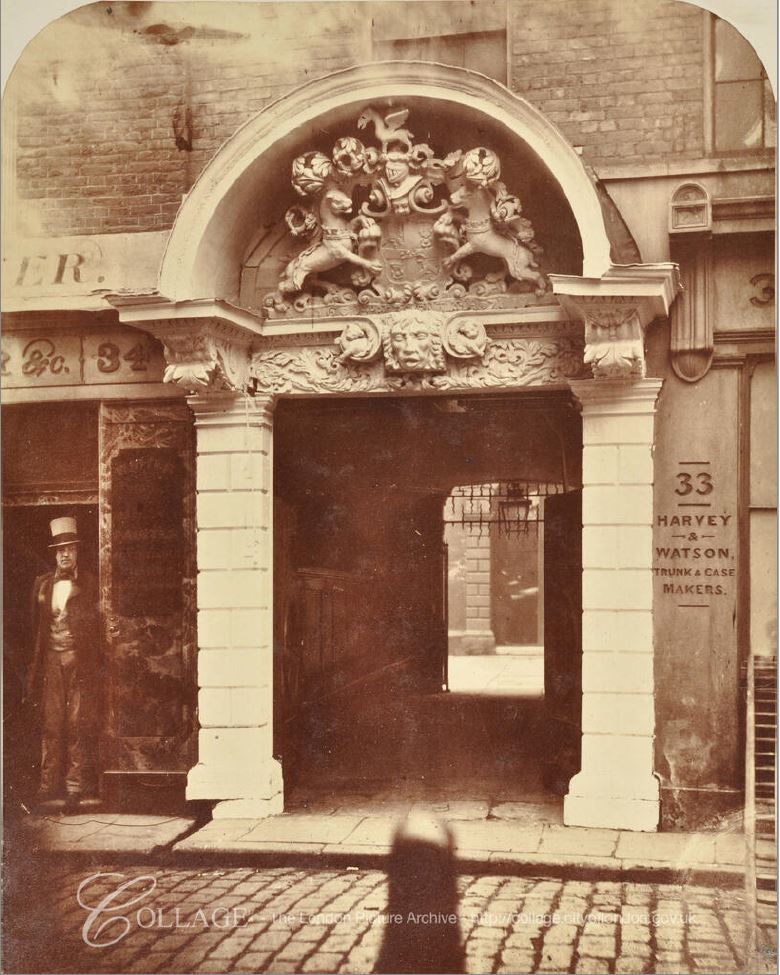

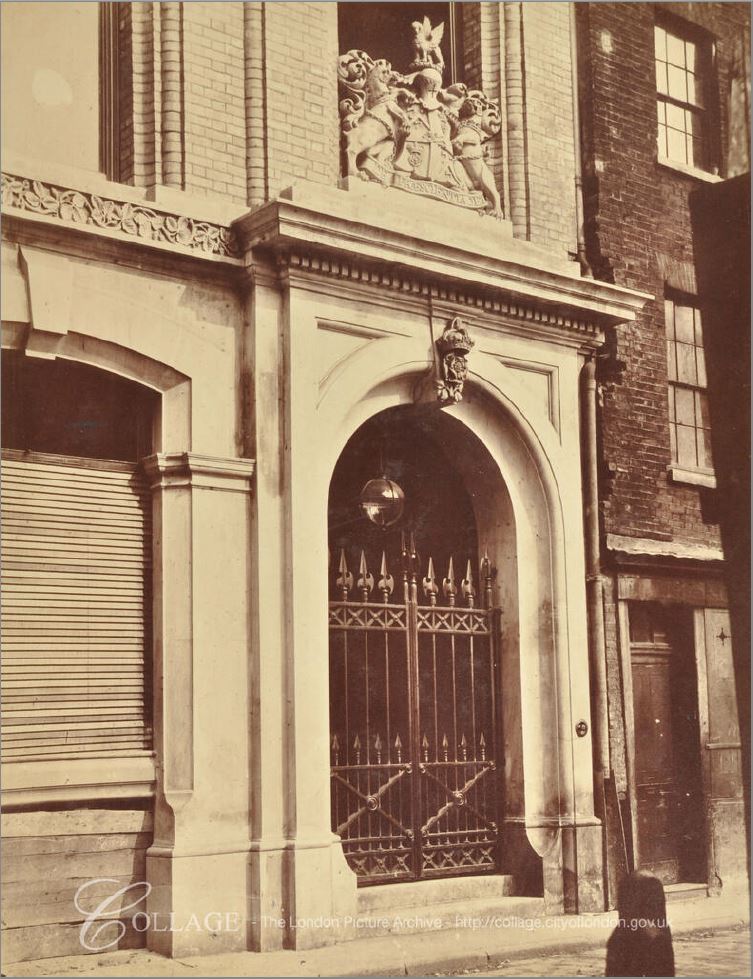

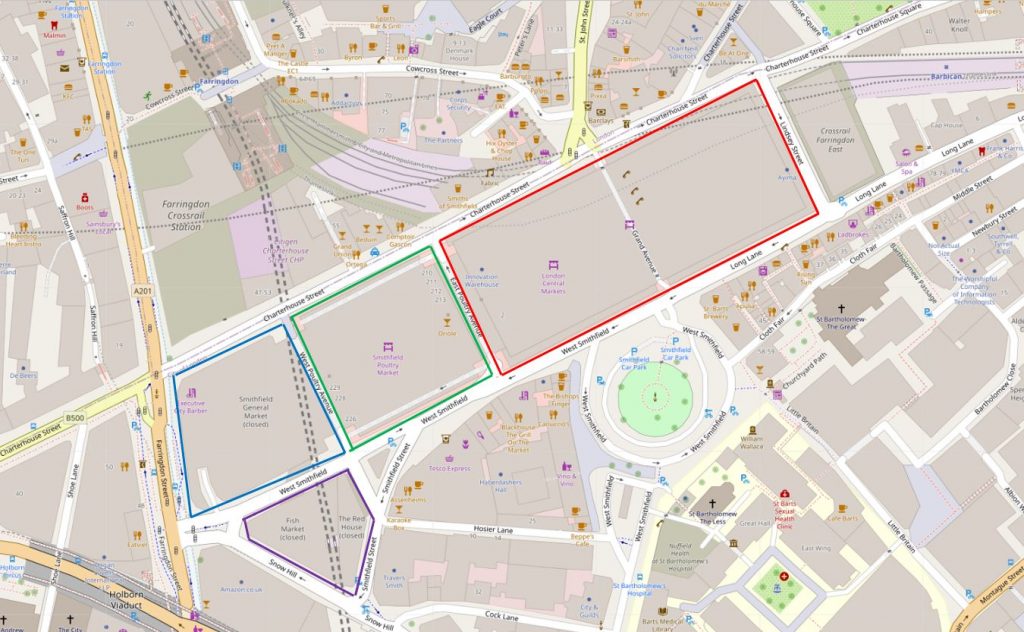

St. Batholomew’s Hospital: The West Entrance

The western edge of the hospital is similar today, but a very different hospital can be found behind. The church behind the gate is St. Bartholomew the Less, founded at the same time as the hospital.

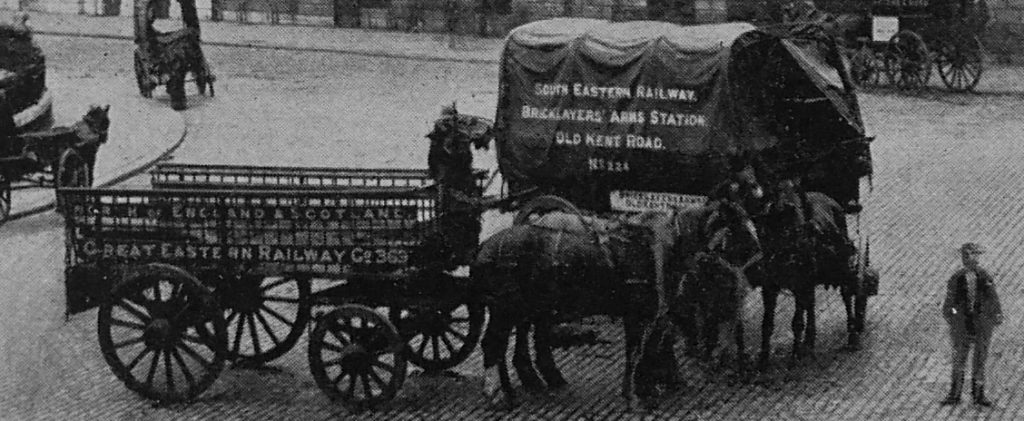

In almost all of these photos, there are little details that add to an understanding of how London functioned at the time. There are some horse and carts in the centre of the above photo. Enlarging these we can read the text on the side.

These were the “white vans” of the time – the delivery vehicles of the Great Eastern railway. The one on the right being number 224 from the Bricklayers Arms Station, Old Kent Road. These, along with carts from the other railway companies, would be seen all across London, collecting and delivering goods for transport on the railways.

Drury Lane, Theatre Royal

Drury Lane Theatre was founded in 1663. The building shown in the photo was built between 1811 and 1812. The Queen’s London refers to the theatre being famous for its Christmas pantomimes.

The Mile End Road

The view is looking east along the Mile End Road from the junction with Cambridge Heath Road.

On the left of the photo is the Vine Tavern, a pub possibly dating back to 1625, but demolished not long after the photo was taken, in 1903. If the photographer had looked to the left, we would see the pub on the corner of Mile End Road and Cambridge Heath Road – the White Heart – a pub which is still there today.

The Victoria Embankment, From Westminster Bridge

The photo is from Westminster Bridge, with one of the “floating steam boat piers” shown to lower left. Two of the steamboats that carried passengers between piers along the river are seen. The lower boat is now on its way to London Bridge, whist the second boat is arriving at Westminster Bridge, before departing for Chelsea – a 19th century version of the Thames Clippers that transport passengers along the river today.

The Queen’s London provides a snapshot of London at the very end of the 19th century. The city had changed much over the previous century, and would change again during the following 100 years. Considerable damage during the Second World War, the loss of industry and the docks, and the growth in height of many of the new buildings of the later decades of the 20th century.

The Queen’s London also provided a very positive view of London, from a particular perspective. The nearest the book gets to showing working class homes are the Weavers Houses of Florida Street. There are no photos of the crowded and poor condition housing that remained.

Given how much has changed, many of the scenes are still very similar, and if a reader from 1896 was standing on Westminster Bridge today, the view would still be very familiar.