The River Thames is at the heart of London, it is the reason for London’s existence.

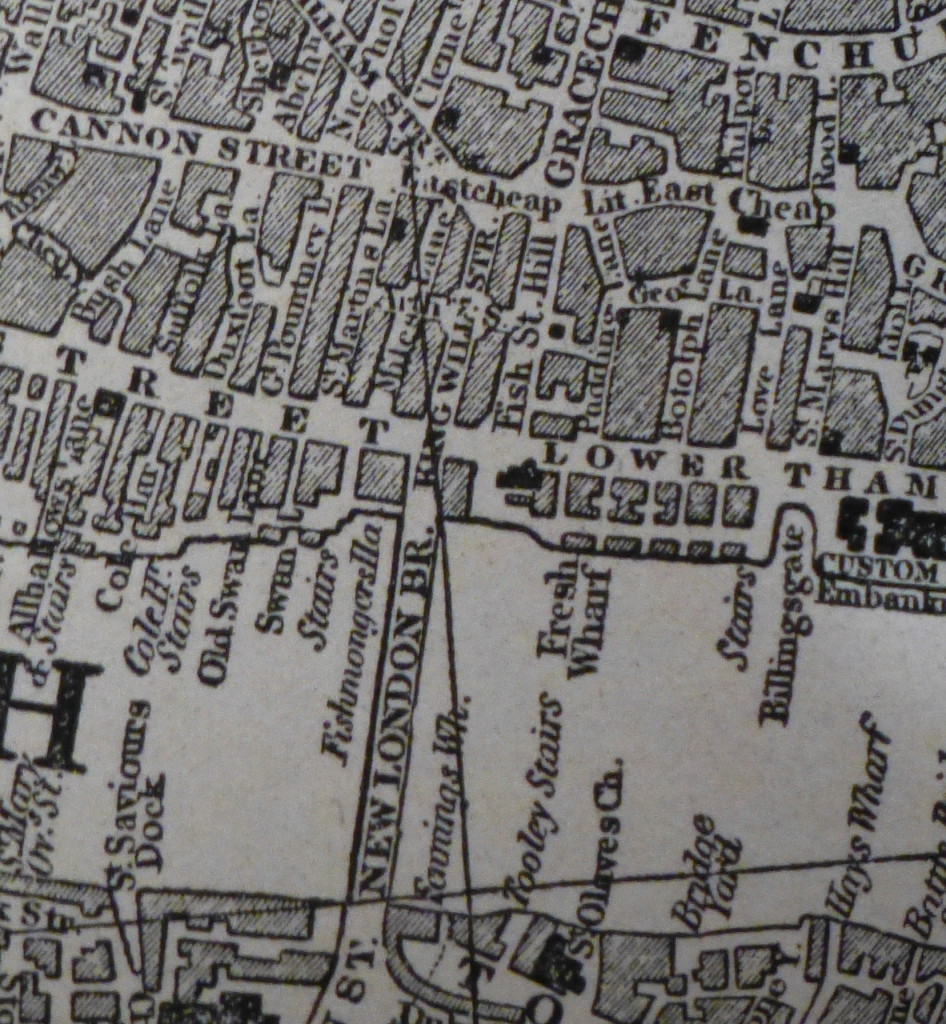

Coming from the sea, the location of London was the first point where it was relatively easy to bridge the river, probably the reason why the first Roman settlement was established.

For the centuries to come, the river allowed London to trade with the rest of the world and supported the growth of the businesses needed to finance and insure, trade the goods shipped through the port and the industries that used the raw materials delivered by the river and exported their manufactured products back out to the world.

Until the last few years, the river provided employment for thousands of Londoners with a high percentage of the country’s trade passing through the London docks.

The river provided London’s connection with the sea and the rest of the world.

Today, the docks have left central London, the river is quiet and very few Londoners have any real connection with the river.

The Thames now adds value to the expensive apartments built along the bank, it is something to be bridged, it is sometimes seen as a risk bringing the potential of flooding to the city.

Apart from the occasional visiting ship, the daily ebb and flow of the tides are now the only connection for most Londoners with the distant sea.

I had my first trip down the river in 1978, and since then it has been fascinating to watch how the river has changed. I also have a series of photos that my father took on a similar journey in the late 1940s. I am working to trace the exact locations and will publish these in a future post.

A couple of weeks ago I took the opportunity for another trip down the river aboard the Paddle Steamer Waverley, from Tower Pier out to the Maunsell Forts.

The Paddle Steamer Waverley is the last sea going paddle steamer in the world, built on the Clyde in 1947 to replace the ship of the same name sunk off Dunkirk in 1940. The Waverley is now run by a charity, the Waverley Steam Navigation Co. Ltd.

In my hurry to get on-board, I forgot to take a photo of the ship moored at Tower Pier, however photos and details can be found on the Waverley’s web site which can be found here.

This is a very brief run along the river. Such a journey really does demand more time and research, however I hope it will illustrate the rich history of London’s river. My photos are also straight out the camera with no processing and under changing lighting conditions, so I apologise for the variable quality.

Over the coming week I will cover:

- Tower Pier to Greenwich

- Greenwich to Barking Creek

- Barking Creek to Southend

- Southend out to Sea

- An Evening Return to London (when the Thames takes on a whole new personality)

Join me today and for the next few days to explore the river, starting today at Tower Pier through to Greenwich.

After leaving Tower Pier, the Waverley is being towed out towards Tower Bridge.

Passing underneath Tower Bridge. Unfortunately shooting into the sun.

On the southern bank of the river, adjacent to Tower Bridge is the old Anchor Brewery building, with to the lower right of the building, Horselydown Old Stairs.

On the north bank of the Thames, just after passing Tower Bridge is the entrance to St. Katherine’s Dock. Built on 23 acres of land on which stood the original foundations of the St. Katherine Hospital, a brewery, 1,100 houses and a church – St. Katherine by the Tower.

The last service took place at the church on the 30th October, 1825 and work on the dock commenced in 1827 with the first stone being laid on May 2nd 1827. The docks were badly damaged by wartime bombing and with the docks being unable to accommodate the growth in the size of ships, never returned to their pre-war volumes in shipping and goods, finally closing in 1968. Much of the area has been redeveloped, however some of the original warehouses remain and the old docks are now occupied by a marina.

Next along on the north bank is HMS President, the shore based location of the Royal Naval Reserve Unit for London. The Navy have occupied the site since 1988 following the sale of the ships HMS President and HMS Chrysanthemum. It was formally the P&O London ferry terminal.

We then come to the first new developments on the north bank of the Thames, not continuing the architectural style of the warehouses that ran along this part of the river. On the river are moorings provided specifically for historic vessels provided by Heritage Community Moorings.

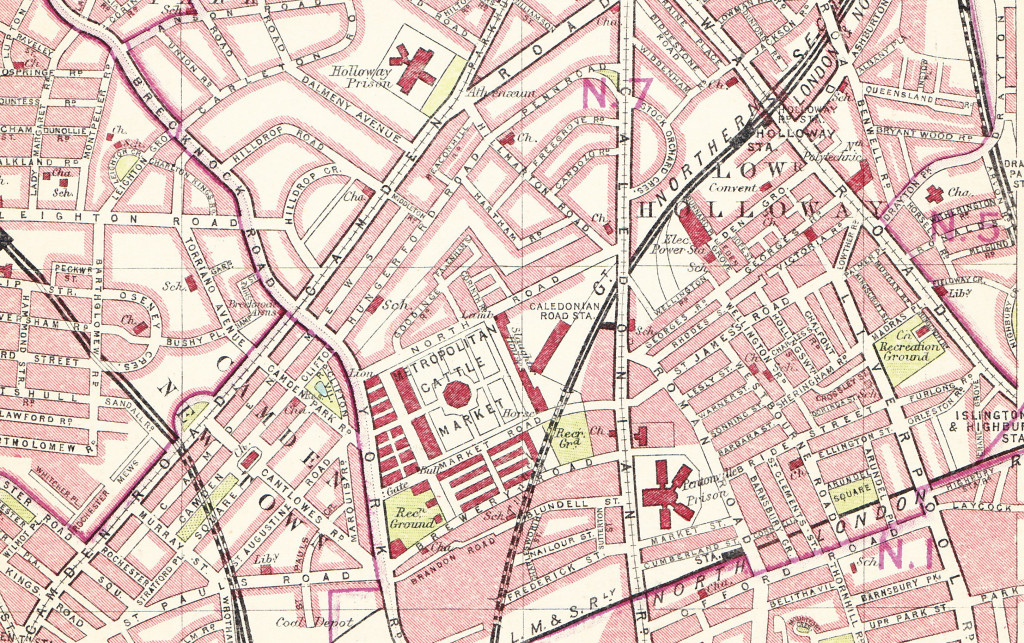

Here is Wapping Pierhead, the original entrance to the London Docks. On either side of the dock entrance is a terrace of Georgian Houses built between 1811 and 1813. The entrance held a lock which was 170 feet long and 40 feet wide, providing access between the river and the London Docks.

During the 1930s the importance of the London Docks declined, again due to the ever increasing size of shipping and the entrance being unable to accommodate the larger ocean going ships.

The London Docks were gradually closed during the 1960s when the Wapping entrance was filled in. The gardens built on the filled in lock can still be followed back across Wapping High Street.

Adjacent to Pierhead is Oliver’s Wharf, named after George Oliver for whom the wharf was built in 1870. Oliver’s Wharf has the distinction of being one of the first riverside wharfs to be converted into luxury apartments. The steps on the left side of Oliver’s Wharf are Wapping Old Stairs and lead up to the Town of Ramsgate pub. A pub has been on the site since the 15th century. It was known as Ramsgate Old Town from 1766 and in 1811 took the current name, Town of Ramsgate. The Ramsgate connection is reputedly down to the use of the stairs by fishermen from Ramsgate to bring ashore their catch.

The area around the base of Wapping Old Stairs is also assumed to be location where those found guilty of piracy were hanged and left in the water until three tides had passed over their bodies.

Passing Oliver’s Wharf, the expanse of the Thames opens up with the towers of Canary Wharf on the Isle of Dogs in the distance. The river today is very quiet compared to how it would have been for much of London’s existence. This photo also illustrates how the river curves and loops. Here it curves to the left before embarking on a wide loop around the Isle of Dogs, taking the river to the extreme right of the photo.

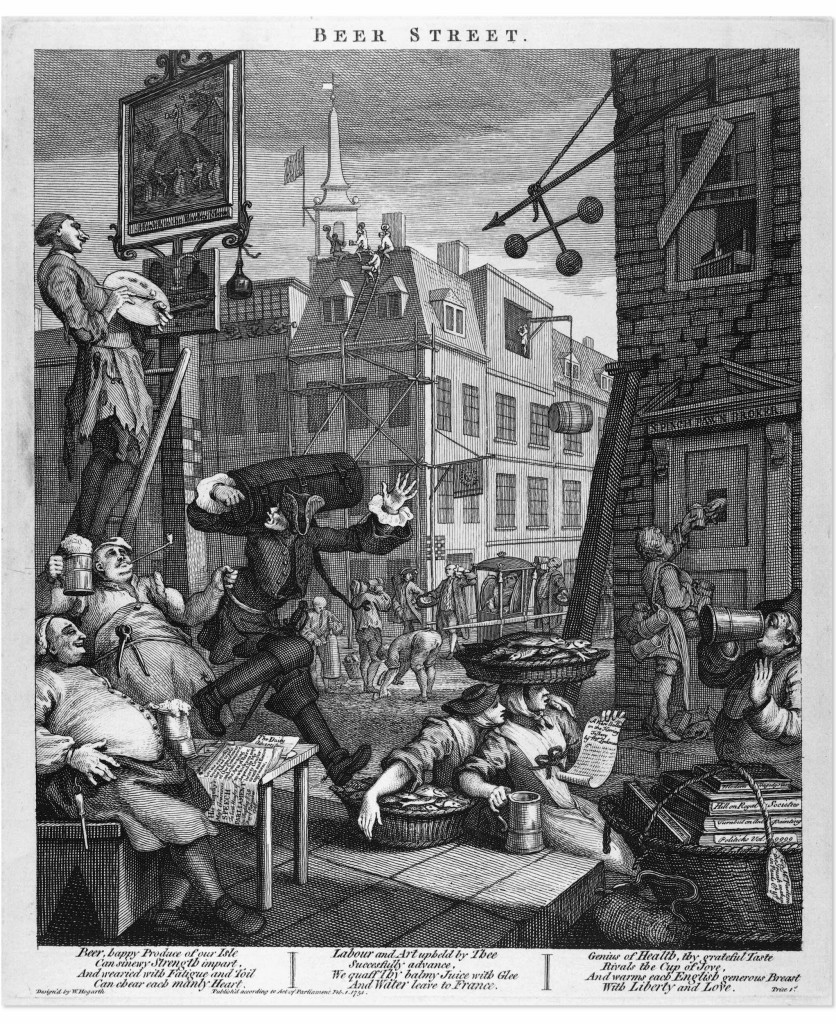

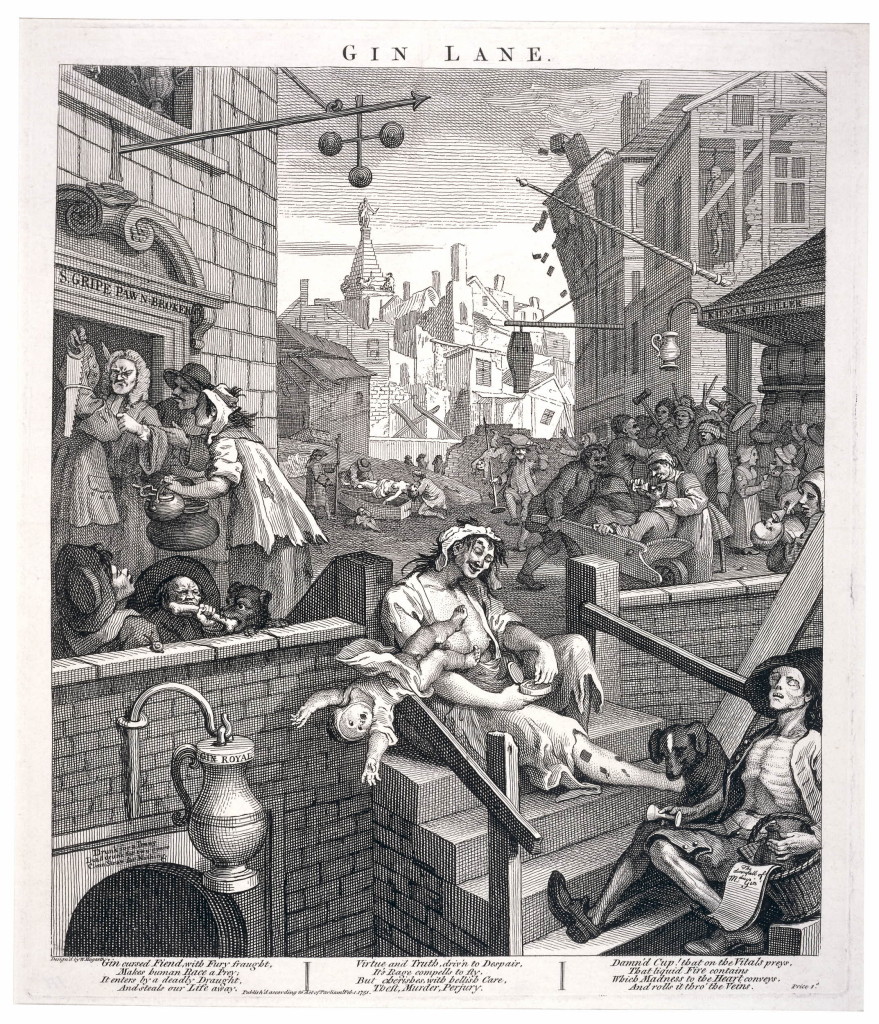

How the Thames has been the route for trade during the centuries is highlighted by three quotes used by A.G. Linney in his book “Lure and Lore of London’s River”:

“To this City, Merchants bring in Wares by Ships from every Nation under Heaven. The Arabian sends his Gold, the Sabean his Frankincense and Spices, the Scythian Arms, Oil of Palms from the plentiful Wood: Babylon her fat Soil, and Nilus his precious Stones; the Seres send purple Garments; they and Norway and Russia Trouts, Furs and Sables; and the French their Wines.” – Fitzstephen, a Twelfth-Century Monk

“The wealth of the world is wafted to London by the Thames, swelled by the tide; and navigable in merchant ships through safe and deep channel, for sixty miles, from its mouth to the City; its banks are everywhere beautified with fine country seats, woods and farms.” – Paul Hentzner, a Seventeeth-Century Visitor to England

“One hundred thousand men, dockers, stevedores, lightermen, sailors, and kindred callings depend upon the Port of London; and all of them subsist and owe their livelihood to the bountiful favour of Father Thames.” – John Burns, a Twentieth-Century London Lover

How this has changed we can explore as we travel down the river.

To protect the ships on the river and the goods they carried, the River Thames has one of the earliest established police forces in the world. The Marine Policing Unit was originally set-up in 1798 following a spate of thefts from shipping in the Pool of London. The original police station for the Marine Policing Unit was in Wapping, and although the original building has been replaced by one constructed in 1907, the head office and main operating base continues on the same site. The Marine Policing building in the centre with the Police pier on the river:

In the above photo, the building to the right is St. John’s Wharf. This building and those in the photo below were all originally part of the St. John’s Wharf complex. The buildings facing the Thames are all original, however the Captain Kidd pub is new following a 1980s conversion of the building. The building on the right, now called Phoenix Wharf was originally St. John’s (K) Wharf and dates from the 1840s.

Next along are the King Henry’s Wharfs. Originally used for the storage of sugar and coffee. The cranes mounted on the building show two of the types of crane which would have lifted goods from ships to be stored in the wharf building and were a common feature on the wharfs along the river.

Just past King Henry’s Wharf on the north bank is Gun Wharves. These are Grade 2 listed buildings and whilst many of the other remaining wharf buildings date from the 19th century, Gun Wharves are from the late 1920s.

Another original building converted into luxury apartments is New Crane Wharf and for a bit of 1980s nostalgia, the opening part of the video for Katrina & The Waves song Walking On Sunshine was filmed in and around a partially derelict New Crane Wharf in 1985. The video can be found here.

Metropolitan Wharf, another Grade 2 listed building, the overall complex constructed between 1862 and 1898.

We then pass the Prospect of Whitby. A pub has stood on the site for many centuries, with the current building from the early 19th century when the pub took the name allegedly after an 18th century collier registered at Whitby called the Prospect.

Soon after the Prospect of Whitby is the entrance to the Shadwell Basin. The red bridge that can be seen above the dock entrance is the bridge seen in my father’s photo looking down Glamis Road which can be found in this post.

Next along is the entrance to the Limehouse Marina in the original Limehouse Basin. The Limehouse Basin provides access to the Limehouse Cut which runs up to the River Lea and to the Regents Canal. This would have been a busy entrance providing the route for barges to transport goods further inland and around north London.

Just past the entrance to the Limehouse Marina is another historic Thames pub. The Grapes can be seen on the left side of the photo with the tiers of stairs facing the river. Look in the river just to the right of The Grapes and one of Antony Gormley’s statues can be seen standing on a pillar in the river. The statue, called “Another Time” was purchased by Sir Ian McKellen who is a part owner of The Grapes. The statue is best seen from the terrace at the back of The Grapes during a high tide when the plinth is below the water and the figure appears to be standing on the water, forever staring downstream.

The entrance to Dunbar Wharf. A short stretch of water named after the Dunbar’s who started with a local brewery and then went on to own some of the warehouses here and operate a large fleet of ships that carried goods across the world.

Just past Dunbar Wharf we approach the Isle of Dogs and the Canary Wharf office complex that now occupies the site of the West India Docks.

As well as office blocks, much of the riverside of the Isle of Dogs is now occupied by an ever increasing number of apartment buildings.

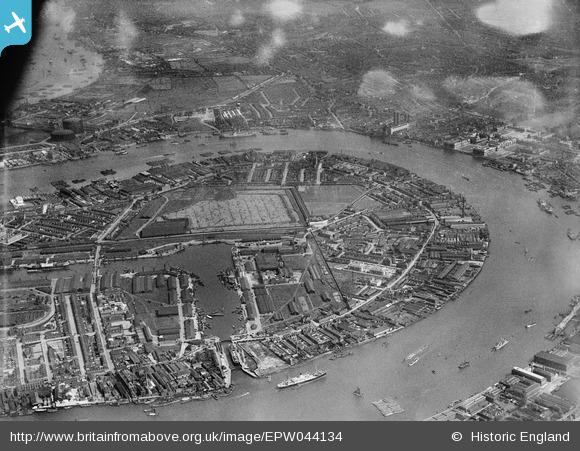

This is the old entrance, now blocked up, to the Millwall Outer Dock, the dock at the southern end of the Isle of Dogs. One of my father’s photos shows the damage caused by a bomb which hit the right side of the entrance to the dock.

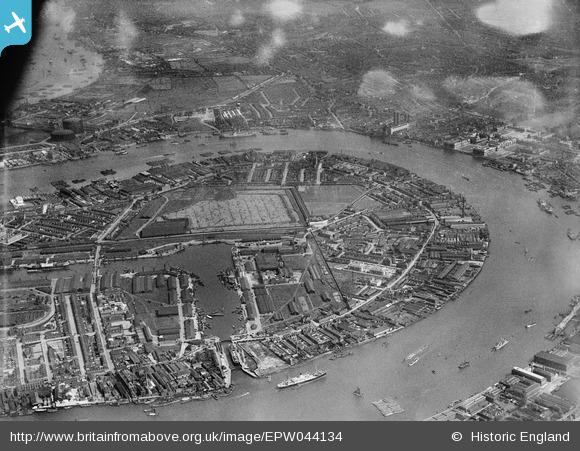

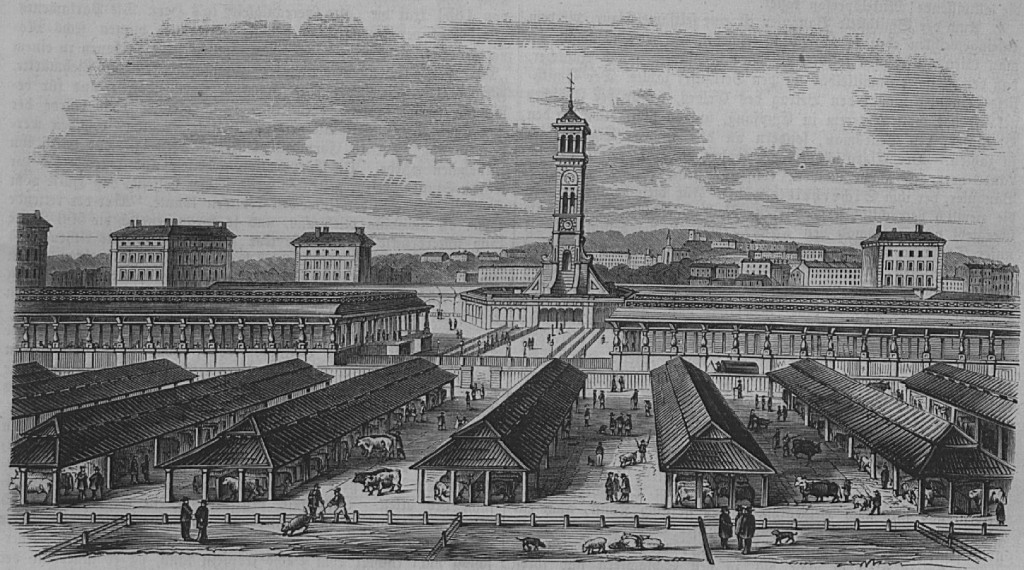

The following photo from the Britain from Above website shows the southern end of the Isle of Dogs in 1934 with the Millwall Outer Dock and its entrance to the Thames.

Looking back at the office blocks of Canary Wharf with the old entrance to the Millwall Outer Dock on the right.

Most of the photos I have taken so far have been of the north bank of the Thames. I must admit I was concentrating on the north bank despite so much of interest on the south as we passed Rotherhithe. The sun was behind the south bank of the river tending to put the buildings along the south bank in shade.

Approaching Greenwich I moved over to look at the south bank and the following photo shows all that remains of Paynes Paper Wharf in Deptford.

The original arches are at the front, with a new development occupying the rest of the site. This was originally a marine boiler factory, built for marine engineers J. Penn & Sons. It was here that HMS Warrior, the ironclad ship (which had been constructed at the Thames Iron Works and Shipbuilding Company based at Blackwall) had her engines built and installed. HMS Warrior is now preserved at the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard.

Production of marine engines ceased in 1911 and the site was later used for paper storage.

The photo below shows the entrance to Deptford Creek. It is just possible to see the new foot bridge that runs across the entrance of the creek to allow the Thames Path to continue without the earlier in-land diversion. The unique feature of the bridge is that it is a swing bridge. To allow ships to pass in and out of the creek, the bridge can pivot on its easterly mounting (the left side of the photo) and swing open towards the Thames.

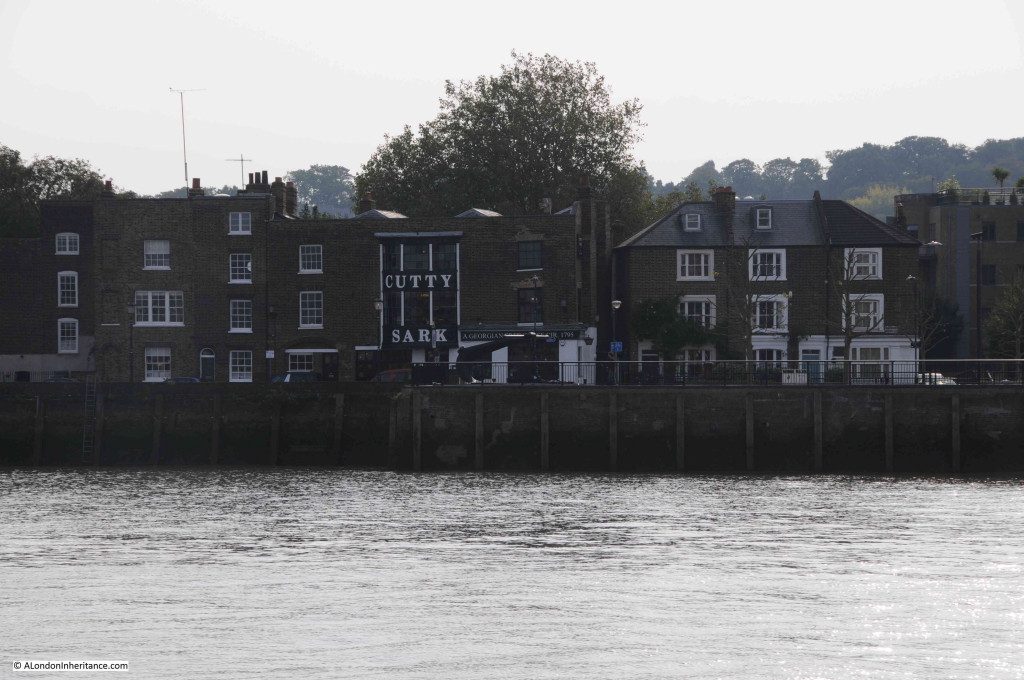

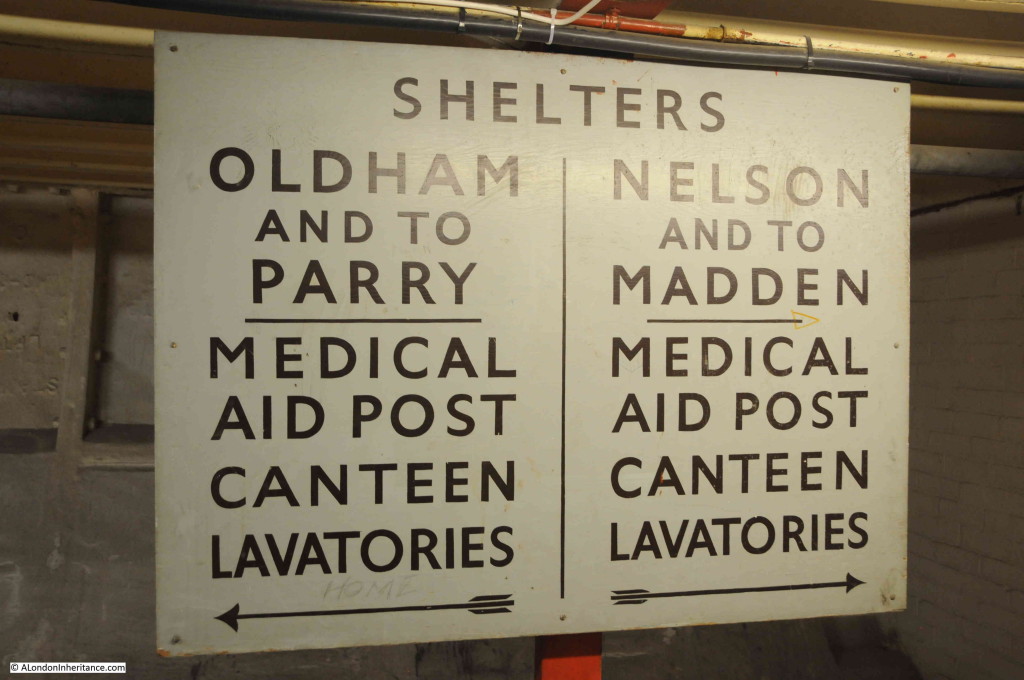

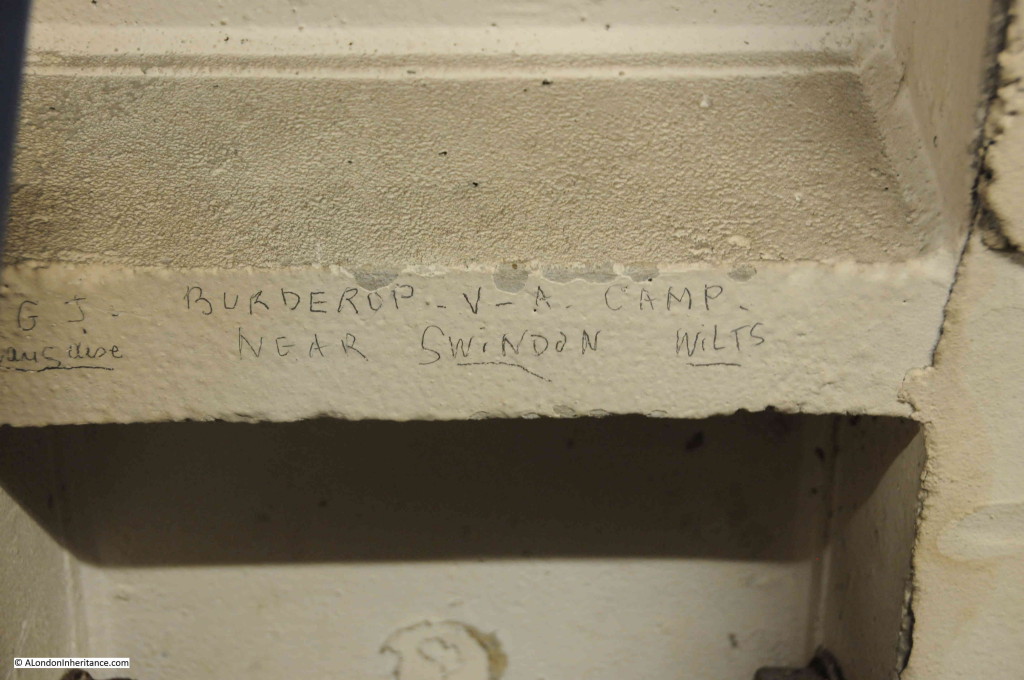

Arriving at Greenwich with the entrance to the foot tunnel and the Cutty Sark.

The Waverley did not stop at Greenwich this year, however to finish this section of the journey, the following photos show the arrival at Greenwich when I took the same journey in 1978:

Greenwich has always held an important role in the life of Thames. Originally the site of a Royal Palace, reached by the river and the birthplace of Henry VIII in 1491, then as a Royal Hospital for Seamen and finally as a Naval College.

Greenwich has always held an important role in the life of Thames. Originally the site of a Royal Palace, reached by the river and the birthplace of Henry VIII in 1491, then as a Royal Hospital for Seamen and finally as a Naval College.

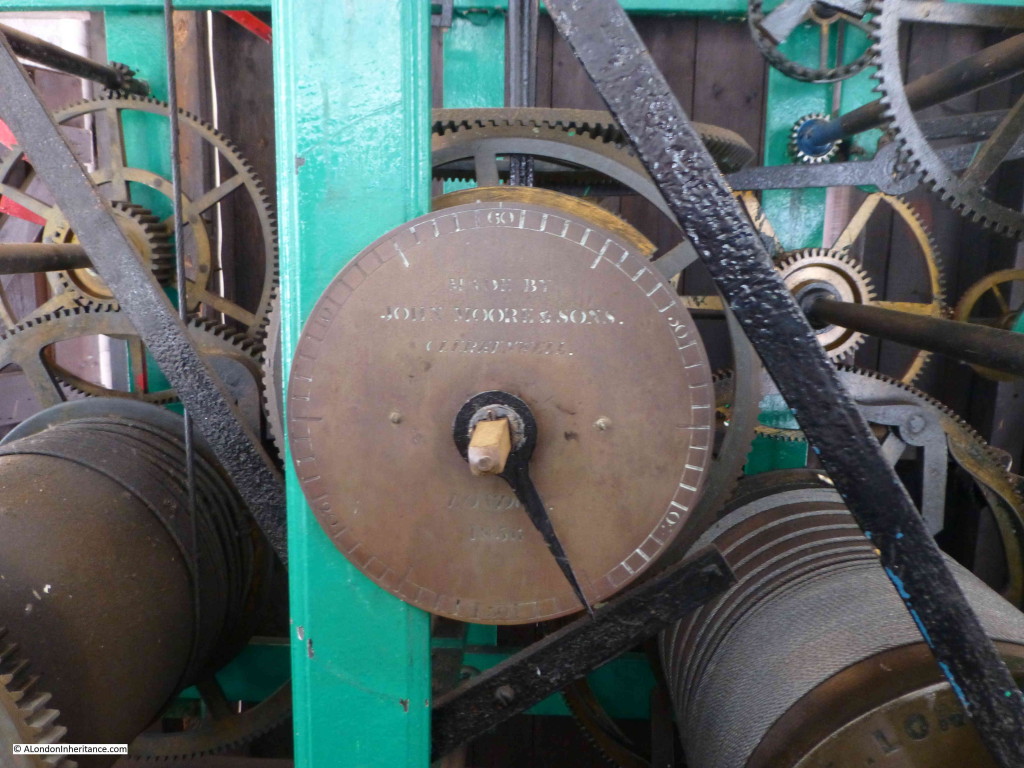

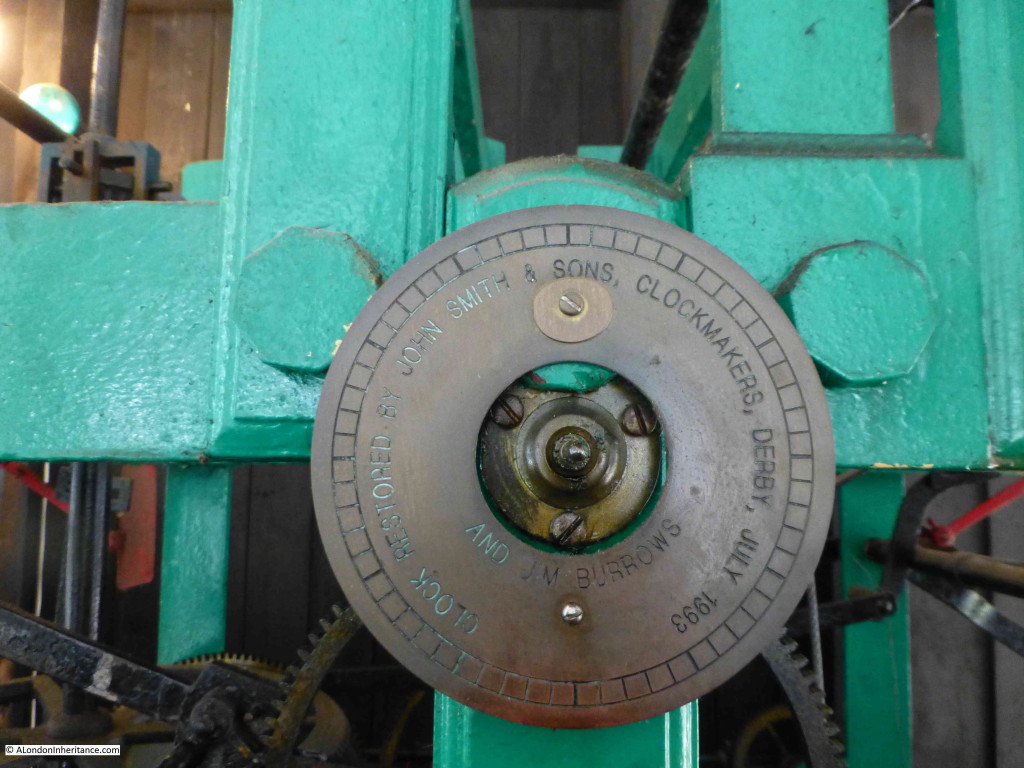

The Royal Observatory on the hill behind played a key part in developing the navigation systems and accurate measurement of time that helped ships navigate the world. The red ball on top of the observatory provides an accurate time signal to passing ships. Starting in 1833 and continuing to this day, the ball rises at 12:55 and drops at 13:00.

Join me in the next post to continue down the river, from Greenwich to Barking Creek.

alondoninheritance.com