There is an area around Archway underground station where the name Whittington, and the symbol of a cat features prominently, and this area is the subject of today’s post, to track down the location of some 1980’s photos, the first of which is of the Whittington Stone and Cat:

The same view, forty years later:

The view is the same, although today the railings are painted black, but this change must have been made some years ago, as the red paint of the railings in my father’s photo is showing through.

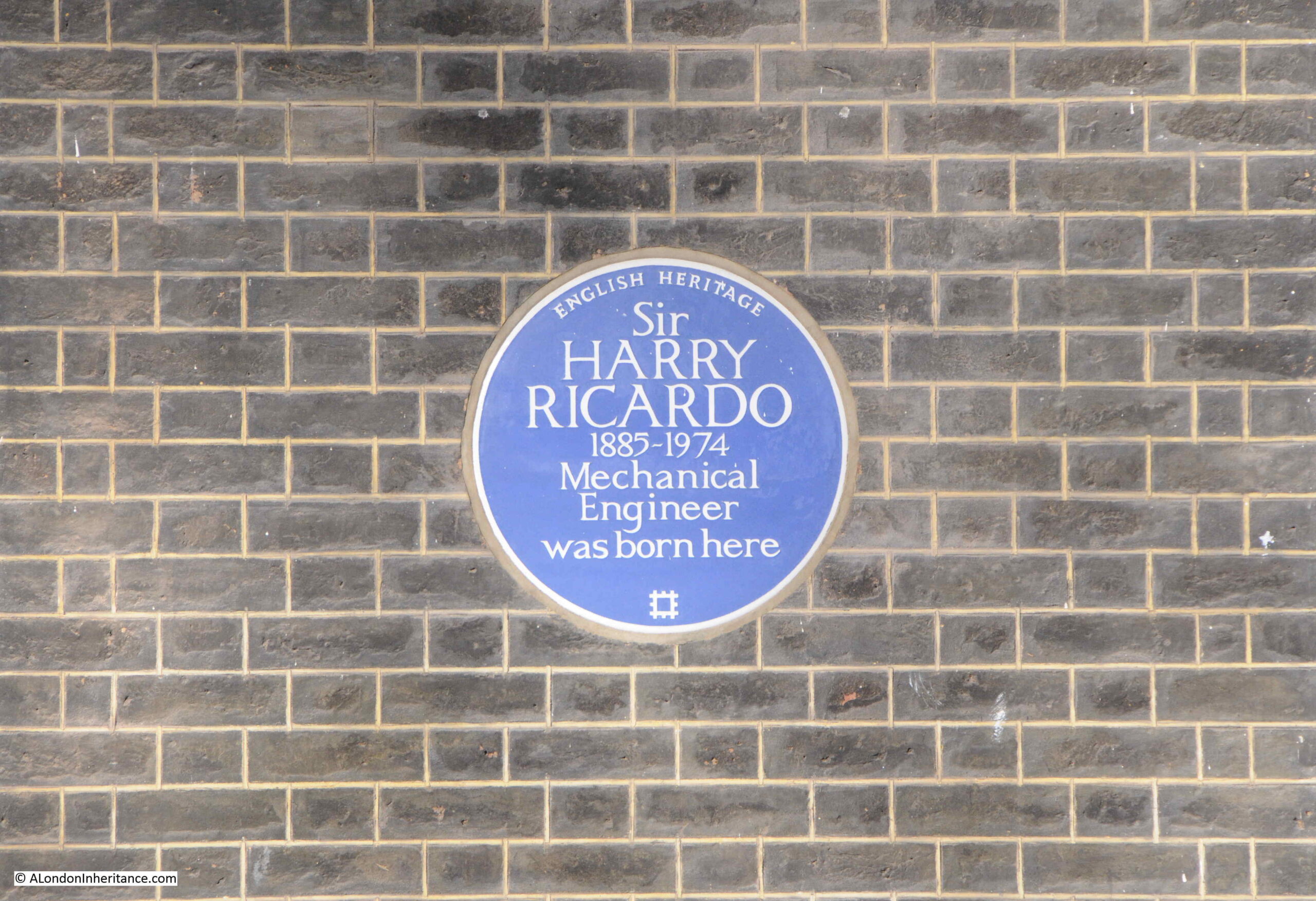

The Whittington Stone is located a short distance north of Archway station on Highgate Hill, at the point where the street starts to run up to Highgate.

The monument is Grade II listed, and the Historic England listing provides some background as to the history of the stone:

“Memorial stone. Erected 1821, restored 1935, cat sculpture added 1964. Segmental-headed slab of Portland stone on a plinth, the inscription to the south-west side now almost completely eroded, that to the north-east detailing the career of the medieval merchant and City dignitary Sir Richard Whittington (c.1354–1423), including his three terms as Lord Mayor of London. Atop the slab is a sculpture of a cat by Jonathan Kenworthy, in polished black Kellymount limestone. Iron railings, oval in plan, with spearhead finials and overthrow, surround the stone. The memorial marks the legendary site where ‘Dick Whittington’ Sir Richard’s folkloric alter ego, returning home discouraged after a disastrous attempt to make his fortune in the City, heard the bells of St Mary le Bow ring out, ‘Turn again Whittington, thrice Lord Mayor of London.”

The listing states that the memorial stone was erected in 1821, however it replaced an earlier stone, and I found a number of newspaper records of the existence of a stone from the 18th century, including the following from the 24th of October, 1761:

“Monday Night about nine o’Clock, two Highwaymen well mounted, stopt and robbed a Country Grazier going out of Town, just by the Whittington Stone, of 4s, and his Horse whip. And after wishing him a good Night, rode off towards London.”

A Country Grazier was another name for a farmer who kept and grazed sheep or cows, and the report is a reminder of how in the 18th century, this area was still very rural. Very few houses, and Highgate Hill surrounded by fields.

As the listing records, the stone is the legendary site of where Dick Whittington heard the bells of St. Mary le Bow and decided to return to the City.

What ever the truth of the legend, the inclusion of a cat (which was only added to the stone in 1964) is more pantomime than history, and even in 1824 alternative sources for the cat were being quoted when talking about the stone, as in the following which is from the British Press newspaper on the 6th of September, 1824:

“Towards the bottom of Highgate Hill, on the south side of the road, stands an upright stone, inscribed ‘Whittington’s Stone’. This marks the situation of another stone, on which Richard Whittington is traditionally said to have sat, when, having run away from his master, he rested to ruminate on his hard fate, and was urged to return back by a peal from Bow bells, in the following:- ‘Turn again, Whittington, Thrice Lord Mayor of London’.

Certain it is, that Whittington served the office of Lord Mayor three times, viz, in the years 1398, 1406 and 1419. He also founded several public edifices and charitable institutions. Some idea of his wealth may be formed from the circumstance of his destroying bonds which he held of the King (Henry V) to the amount of £60,000, in a fire of cinnamon, cloves, and other spices, which he had made, at an entertainment given to the monarch at Guildhall.

A similar anecdote to that of the destruction of the bonds, is related of a merchant to whom Charles V of Spain was indebted in a much larger sum; but as Whittington lived long before that time, it is fair to suppose, that, if true at all, the story belongs to the London citizen.

The fable of the cat, by which Whittington is much better known than by his generosity to Hen. V., is however borrowed from the East. Sir William Gore Ouseley, in his travels, speaking of the origin of the name of an island in the Persian Gulf, relates, on the authority of a Persian manuscript, that in the tenth century, one Keis, the son of a poor widow of Siraf, embarked for India, with his sole property, a cat:- There he fortunately arrived, at a time when the Palace was infested by mice and rats, that they invaded the King’s food, and persons were employed to drive them from the royal banquet. Keis produced his cat, the noxious animals soon disappeared, and magnificent rewards were bestowed on the adventurer of Siraf, who returned to that city, and afterwards, with his mother and brothers, settled in the island, which, from him, has been denominated Keis, or, according to the Persians, Keish.”

Keis is the name of the son of the widow in the above story, and still today, Keis is the name of a small Iranian island off the Iranian coast in the Persian Gulf, with much of the island being occupied by what is labelled on Google maps as an “International Airport”.

Whether there is any truth in the story of Keis and his cat, the article serves to illustrate how stories and legends develop and cross boundaries, and how it is almost impossible to be sure of almost any similar stories to Dick Whittington and his cat.

The Whittington Stone with Highgate Hill in the background:

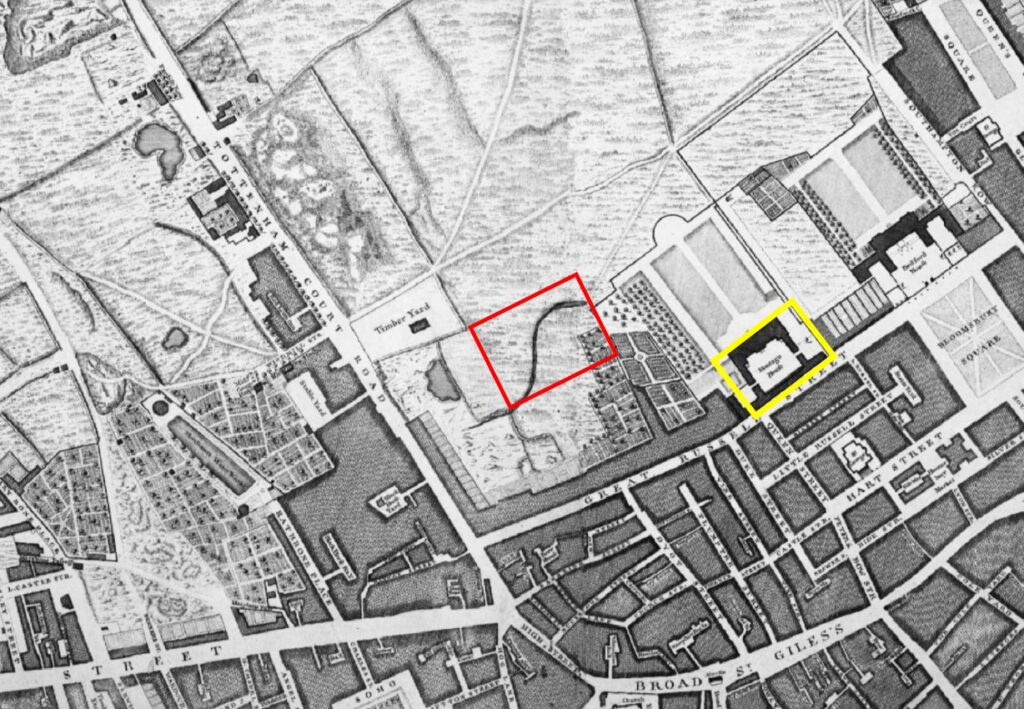

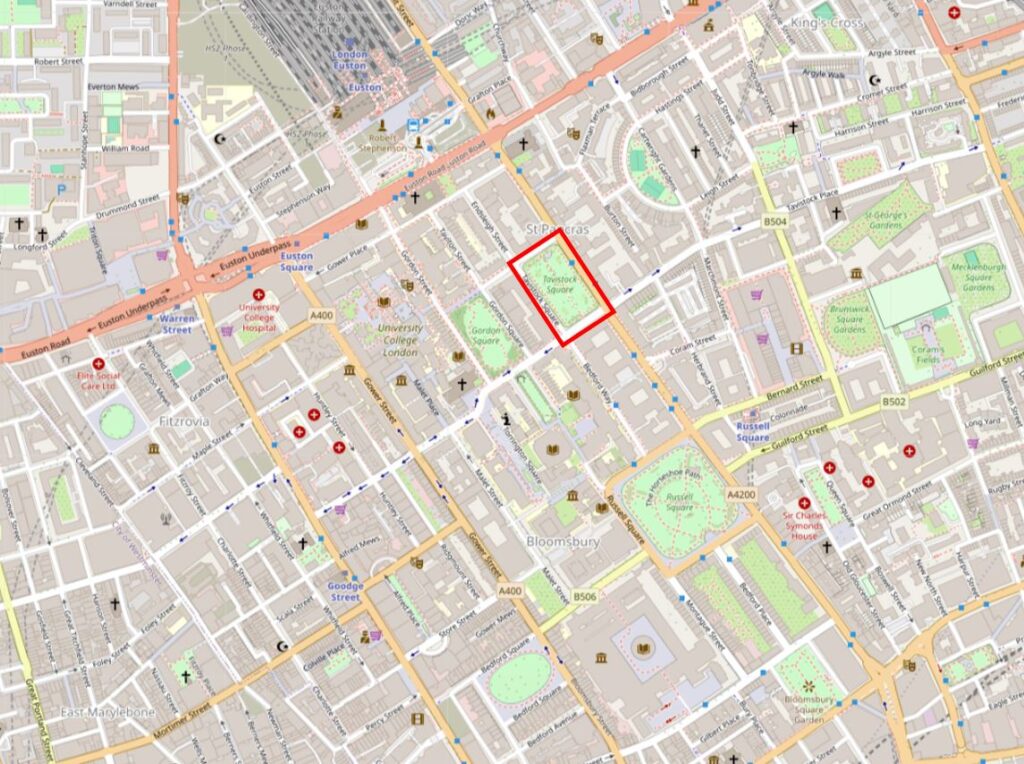

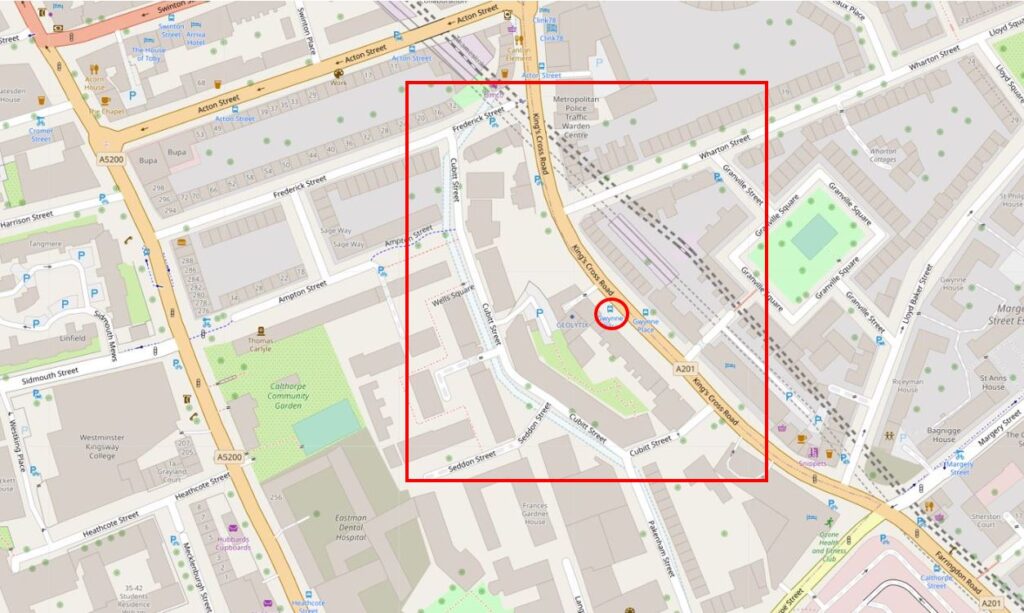

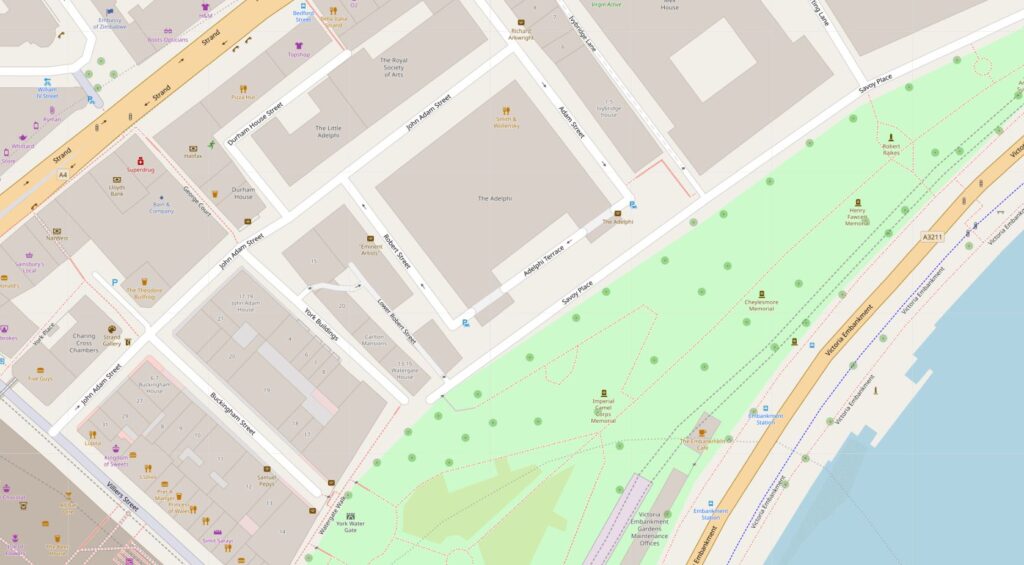

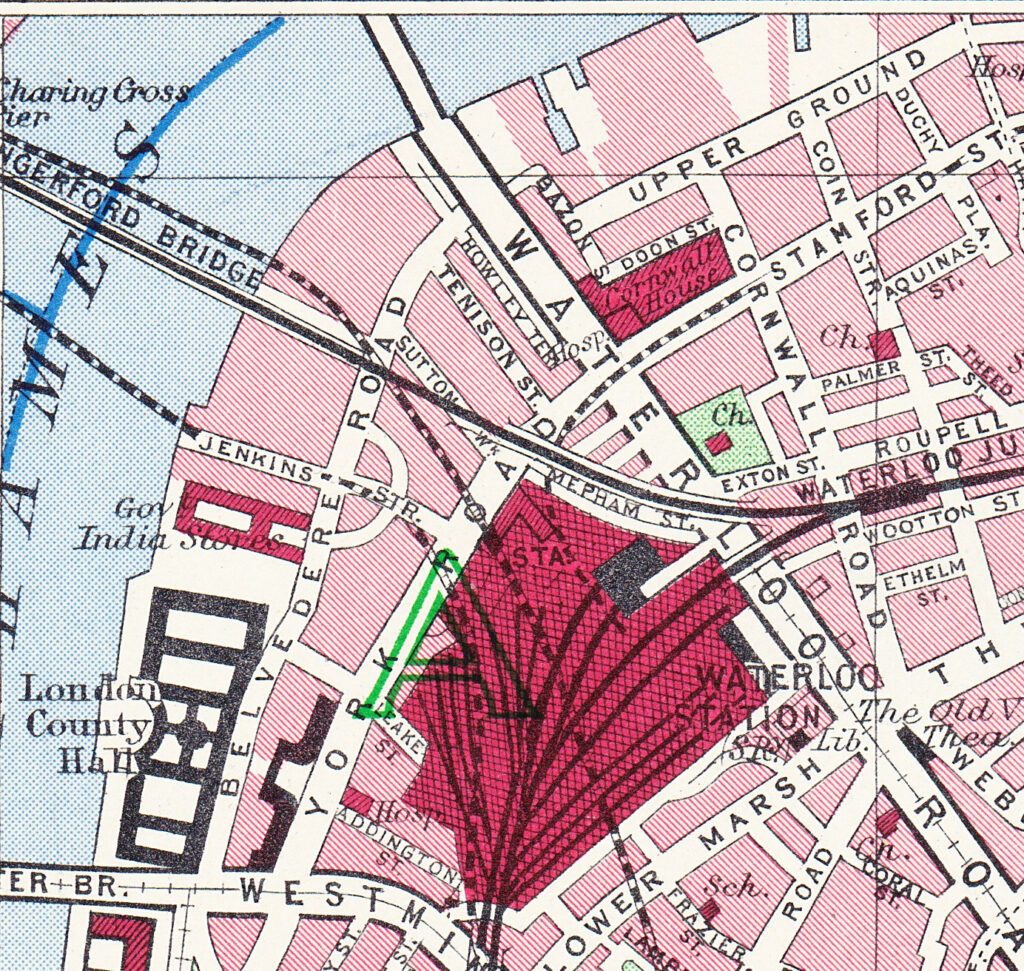

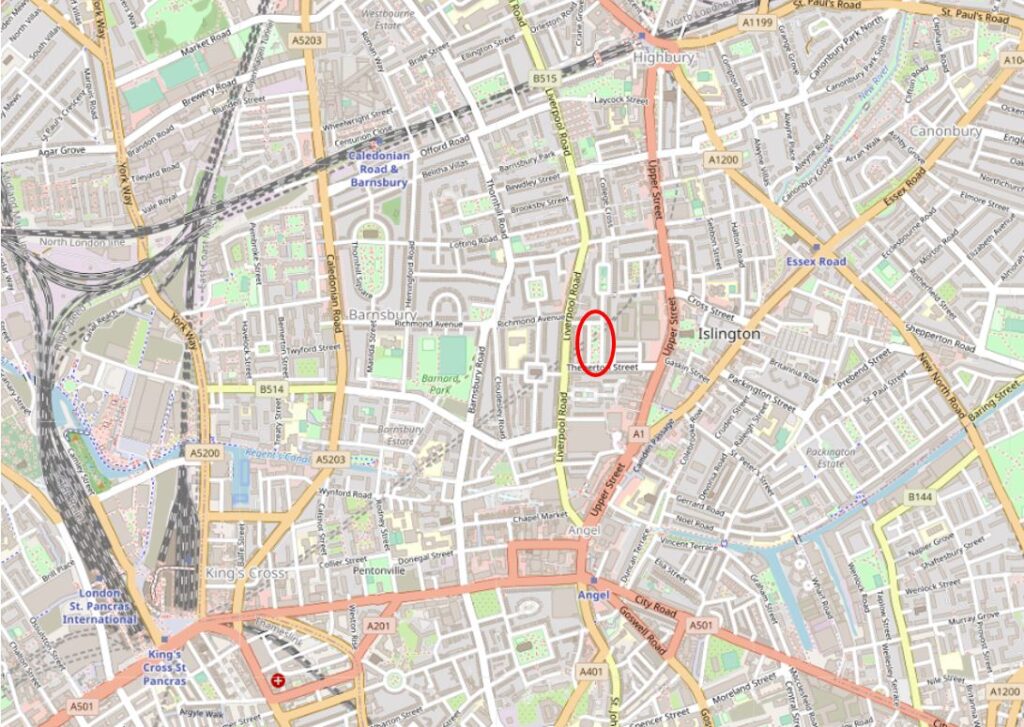

The following map shows the area today, and the red circle marks the location of the Whittington Stone. The red rectangle marks the location of my next stop (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

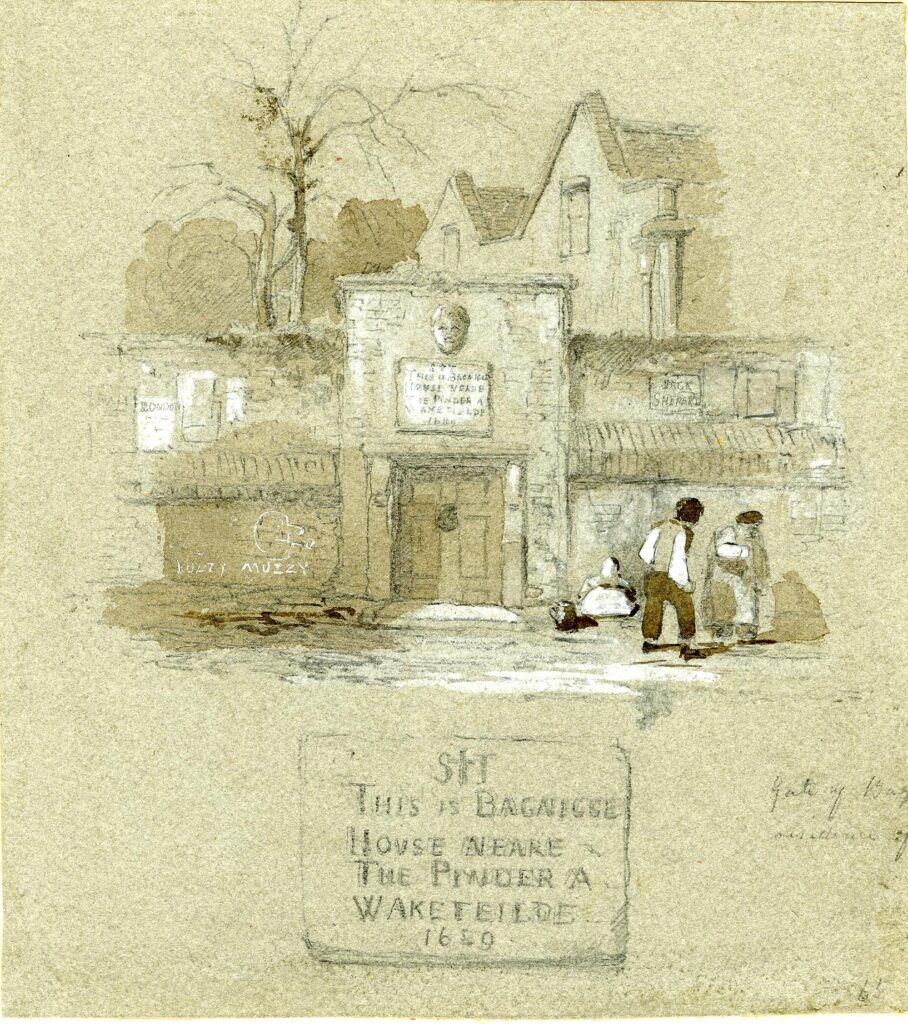

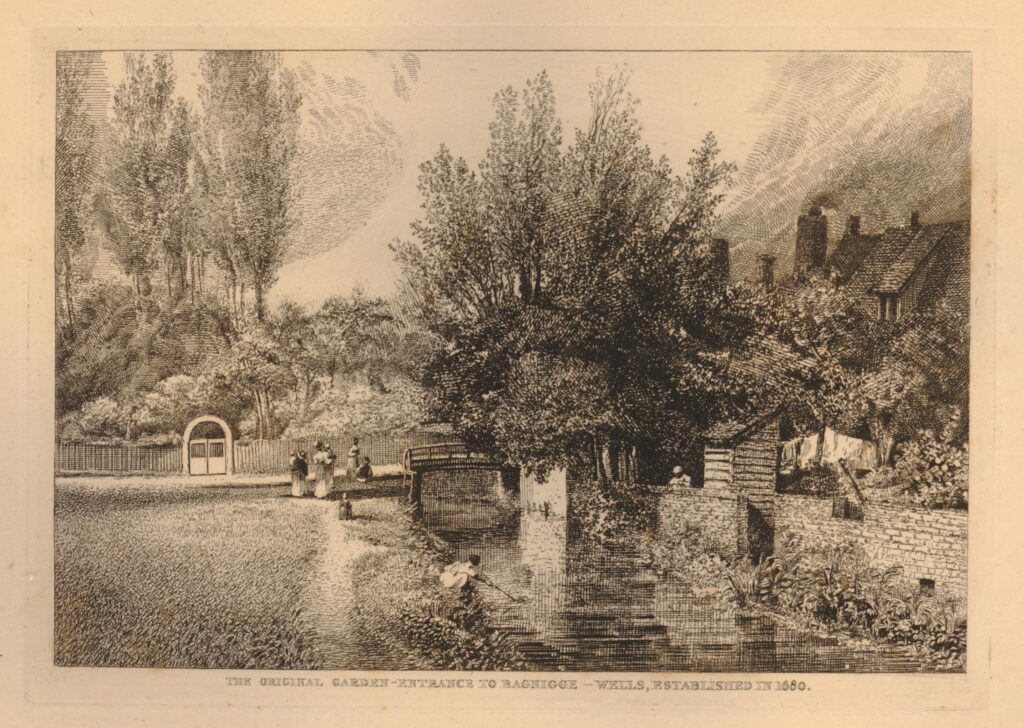

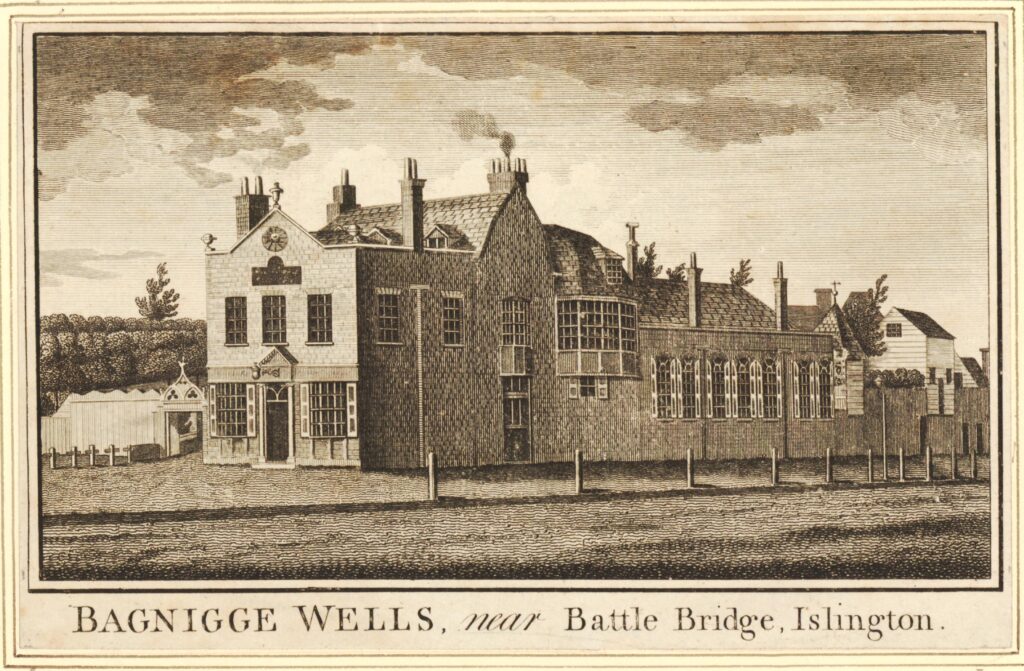

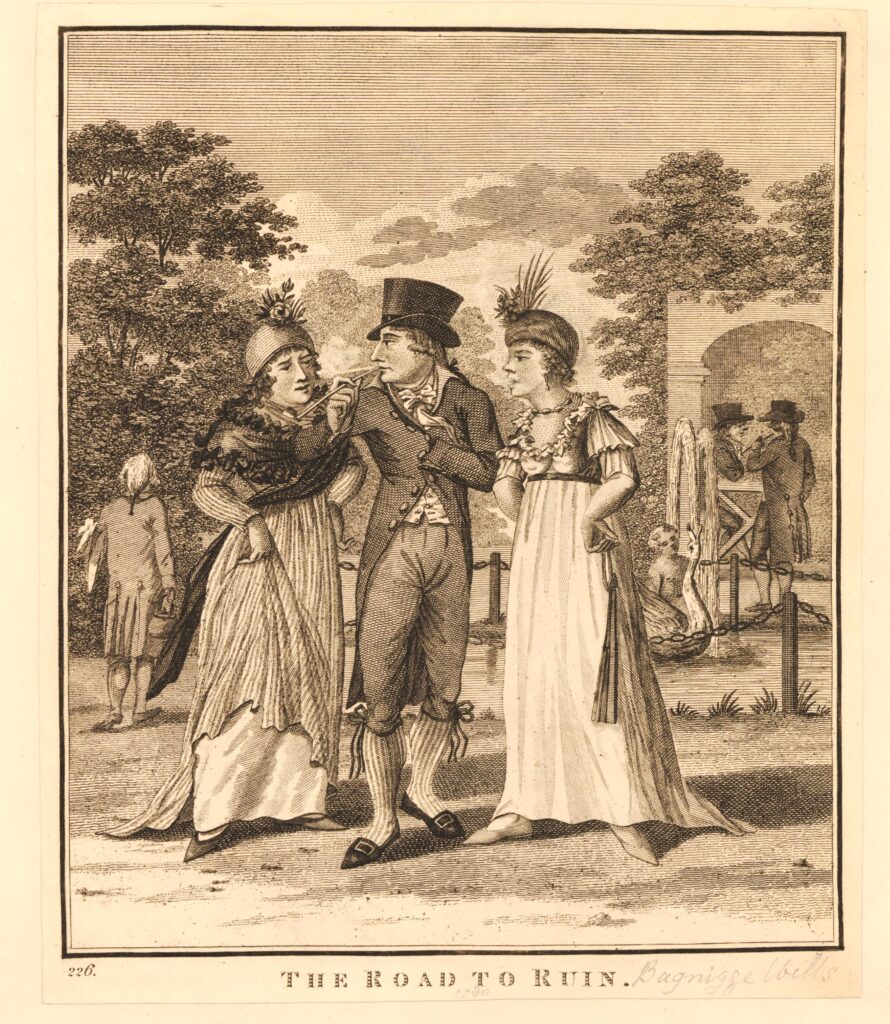

But before leaving the stone, there are a number of prints from the 19th century which provide a rather romantic view of Whittington at the stone.

The following print from 1849 is of Whittington hearing the sound of Bow Bells whilst leaning against what was then described as a “milestone” (and in 1849 there is no cat):

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

A milestone would make more sense, as at the time, Highgate Hill was the main route from London to Highgate.

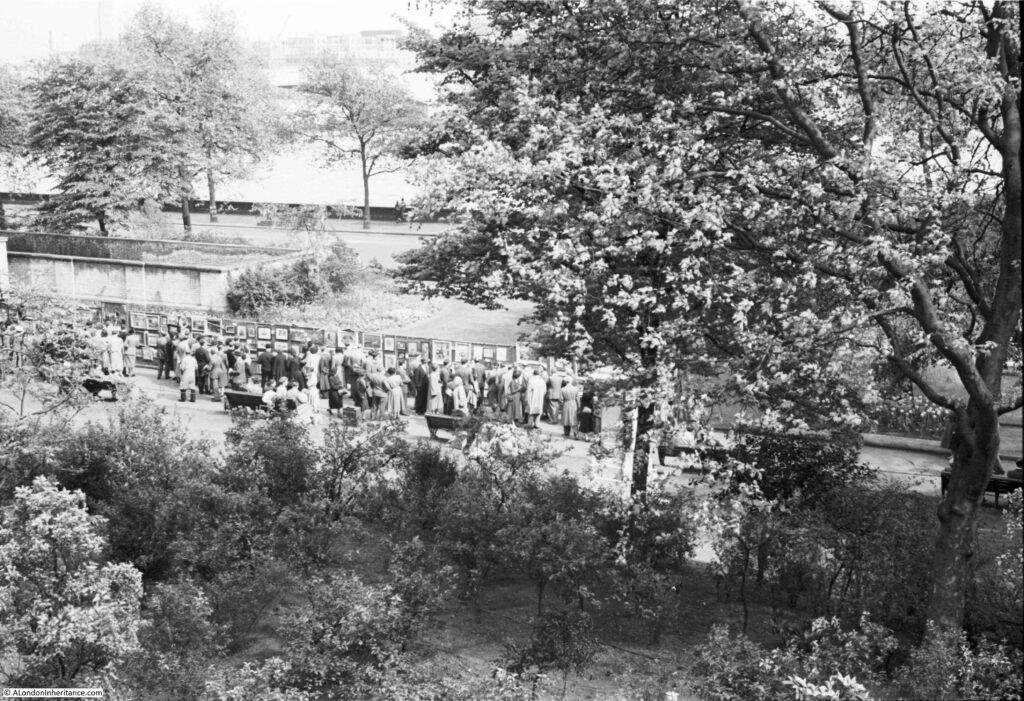

I also looked for views of Highgate Hill and found the following print, dating from 1745 and titled “A Prospect of Highgate from upper Holloway”. The road showing curving up to buildings in the distance is presumably Highgate Hill, and if you look carefully to the right of this road where it starts to curve to the right, there appears to be some form of stone monument:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

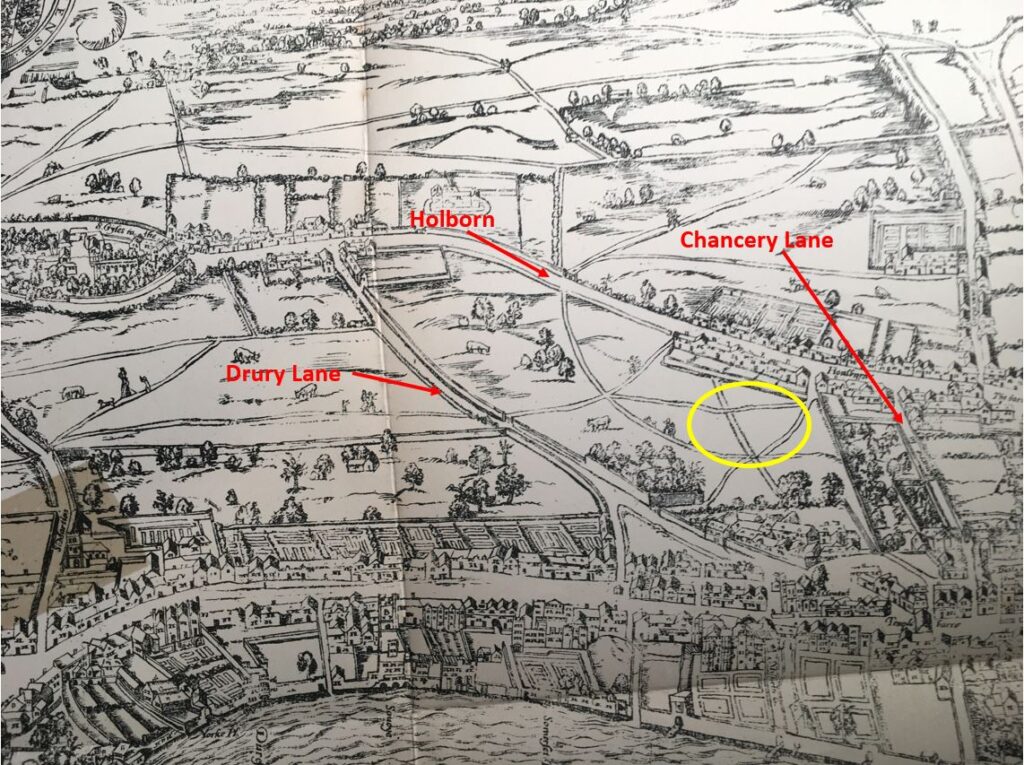

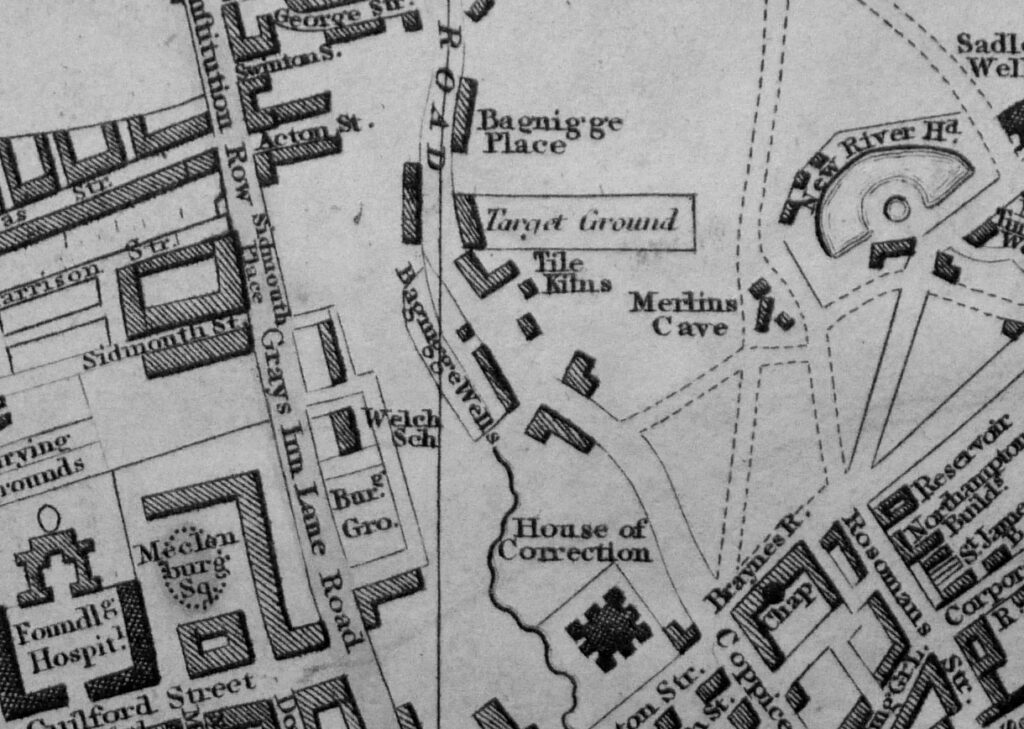

The problems I have with this print is that Highgate Hill did not curve as shown in the print. The following extract from Rocque’s map of 1746, so the same time as the above print, shows the area between Upper Holloway and Highgate (top left). The location of Archway is circled, and the approximate location of where the stone is today is marked:

Another example of how difficult it is to be sure of stories, the appearance of places, and the history of artifacts such as Whittington’s stone.

Whittington’s name, and the symbol of a cat can be found in many places around Archway. Next to the stone is the Whittington Stone pub, a modern version of an earlier pub (I have not included the photo in the post as there were plenty of drinkers sitting outside), and further up Highgate Hill is the Whittington Hospital.

There was another Whittington related place I wanted to find, where my father had photographed some 1980s murals, but before I reached Whittington Park, I found the location of a 1980s photo that I was unsure I would ever find as there were no identifiable features:

Forty years later in 2024:

The shop is on Holloway Road, and is an interesting example of how some types of business occupy the same place for many decades.

Today, the shop is occupied by a hairdresser, as it was 40 years earlier, and judging by the appearance of the place in the 1980s photo, it had already been there for some years.

The persistence of this type of business can be seen in many places across London. Although the names have changed over the decades, they continue to be a hairdresser – a business that cannot be replaced by the Internet, or by changing retail fashions.

The long terrace of buildings on Holloway Road in which the hairdresser is located:

Looking south along Holloway Road, and there is a rather nice painted advertising sign on the side of a building:

A sign advertising “Brymay”, one of the brands of the match manufacturer Bryant & May:

I then reached the Holloway Road entrance to Whittington Park, and it was in this park, 40 years ago, that my father photographed three rather good murals:

The above mural features Dick Whittington sitting on a milestone, along with his cat, both looking back at the City of London (again the stone being a milestone makes sense).

The mural below appears to be a mix of various cartoon and film characters:

And the third mural again features a cat, with a capital W on his tea shirt for Whittington:

The cat shown above was the symbol of the Whittington Park Community Association in the 1970s and 1980s.

Do any of these murals remain?

Next to the entrance to the park there is a pub with a mural on the side:

Not one of those in my father’s photos, but a 2017 variation on the story of Dick Whittington and his cat:

The entrance to Whittington Park from Holloway Road:

To the right of the entrance is a large floral cat sculpture:

And inside the park is another cat. This time in mosaic form, on the ground alongside the main walkway:

I then came to the Whittington Park Early Years Hub, run by the Community Association as a play space for the under fives:

I walked around the building, but any trace of the 1980s murals has disappeared, although there are today painted flowers on some of the walls:

I could not find any other building in the park where the murals could have been located, and the blocks that make up the walls of the building seem to be identical to those in the 1980s photos, so I am sure this is the right place:

Whittington Park is a relatively recent open, green space. In the early 1950s, the site of the park was still a dense network of terrace houses, many of which had suffered some degree of bomb damage.

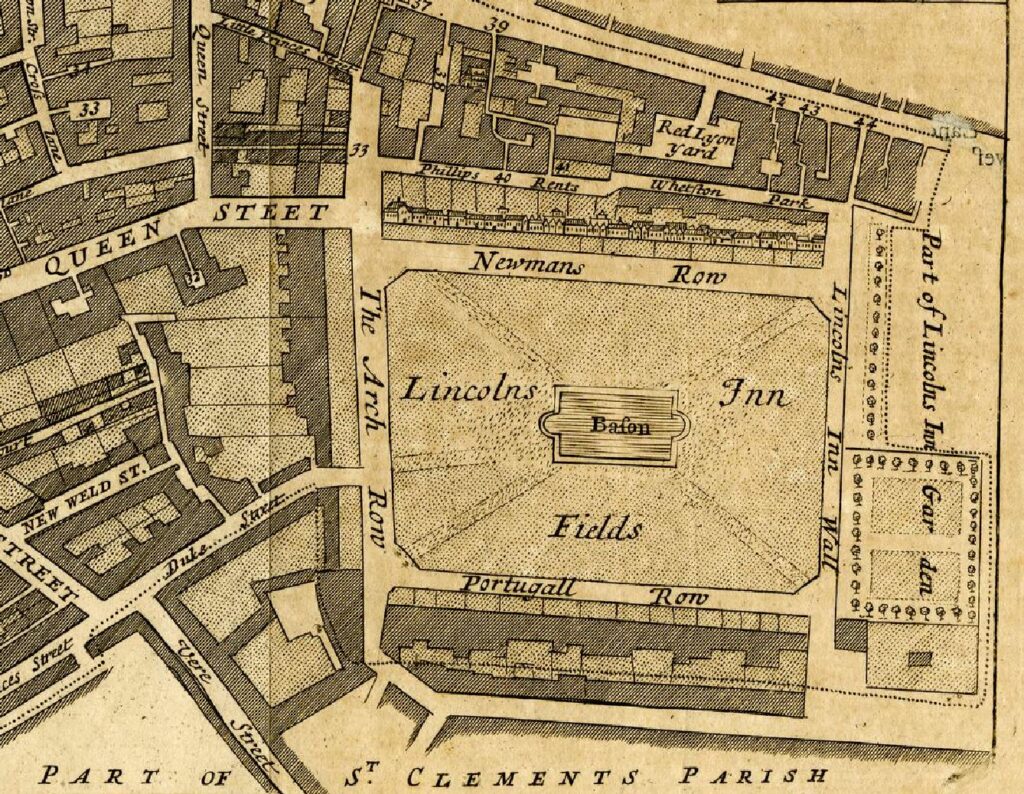

In the following extract from the 1951 OS map, I have marked today’s boundaries of Whittington Park in red, and the map shows the streets and buildings that were demolished to make way for the park (Map ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

It is interesting how much of the London we see today is down to wartime planning for how the future London should develop, and one of these plans was the 1943 County of London Plan by Forshaw and Abercrombie. Part of this plan included proposals to increase the amount of open space that would be available to Londoners of the future, and to address the problems with lack of such space in the way that London had developed from the 19th century onwards.

The North London Press on the 11th of April, 1958 records some of the initiatives in the area, and the small beginnings of Whittington Park:

“Under the County of London Plan, over 100 acres of new open space are to be provided within the borough. In February, 1954, the first part – about an acre – of Whittington Park was opened to the public; this will eventually be extended to form a fine new park of over 22 acres.”

The park would expand over the following decades from the one acre of 1954 to the ten acre site of today, short of the 22 acres expected in 1954;.

The names of the streets that were demolished to make way for Whittington Park all have interesting Civil War connections. There is:

- Hampden Road – named after John Hampden who was a parliamentary leader in opposition to Charles I, and who fought on the Parliamentary side during the war, and died in a fight with Royalist troops at Chalgrove Field, near Thame;

- Ireton Road – named after Henry Ireton who was a leading supporter of Cromwell, and a key figure in the New Model Army, and who went on to marry Cromwell’s daughter;

- Rupert Road – although the above two roads were named after Parliamentary figures, Rupert Road was named after Prince Rupert, who became Commander in Chief of the Royalist land forces. After the restoration of Charles II, Prince Rupert again became a key supporter of the Crown and held high positions in the Royal Navy.

Hampden and Rupert Roads are their original names, however Ireton Road was not the original name for the street. It was originally called Cromwell Road, after Oliver Cromwell.

I suspect the name change was to avoid a conflict with another Cromwell Road, as in the early decades of the 20th century there were initiatives to reduce the number of streets with the same name.

In a walk around the park, I only found a single relic of the streets that were demolished to make way for Whittington Park, and it is a war memorial for those who lost their lives in the Great War and who lived in Cromwell Road.

Today, the monument is set into an earth embankment to the left of the entrance of the park:

I cannot find any firm references as to where the war memorial was originally located, but I suspect that it was on the wall of one of the terrace houses that originally lined the street, in a similar way to the existing memorial at Cyprus Street, Bethnal Green (see this post).

These war memorials for single streets really bring home what the impact of the Great War must have been for small communities and individual streets when you see the number of names of those who died in the war, from one single street.

We can get an idea of what the demolished streets may have looked like, by walking along Wedmore Gardens, which is the street bordering the north western edge of the park. The layout of the houses in the street look very similar to those of the demolished streets, and they are of the same age (the streets were built around the 1860s), so looking along Wedmore Gardens, we get an idea of what was once on Whittington Park:

As well as Wedmore Gardens, Wedmore was also the name of the wider estate of which the streets were part, as well as flats to the south eastern side of Whittington Park, which have since been demolished and replaced with new residential building.

Whether there is any truth in the story of Richard Whittington, or Dick Whittington in his pantomime image, returning to the City of London after hearing Bow Bells, he continues to leave an impression on Highgate Hill and the northern part of Holloway Road, 600 years after his death in 1423.