Today’s post was not on my list of posts to write. Last Sunday, I was in the City to explore a site for a future post. It was a grey, overcast morning, and at one point there was a fine, wind driven drizzle, so I decided to head back home (I should have stayed for the afternoon as the sun came out).

Walking towards the Holborn Viaduct Bridge over Farringdon Street, I noticed another new building site where the previous building had been demolished and construction of the concrete core of the future development was underway.

I walked down from Holborn Viaduct, down to Farringdon Street as I wanted to see if a bit of Victorian construction was visible.

The following photo is from Farringdon Street. Part of the bridge over Farringdon Street is on the left, then there is one of the four pavilions, one on each corner of the bridge, then an open space with the new concrete core of the new building on the right edge of the photo:

Farringdon Street is the route of the lost River Fleet, and the bridge carries the road over what was the river, hence the low level of Farringdown Street, and the slope of the streets on either side.

Walking along the road to cross the bridge, it is not really obvious that the bridge is not the only part of the overall construction of the road, as you are walking along a manmade viaduct of some length.

Holborn Bridge is part of Holborn Viaduct, the 427m long viaduct designed to provide a bridge over the valley of the Fleet River and a level road between Holborn Circus and Newgate Street.

The construction contract for Holborn Viaduct was awarded on the 7th May 1866 and on the 6th November 1869 it was opened by Queen Victoria.

The construction of this 427m viaduct is not that visible, unless buildings along the viaduct are demolished, and it was this that I wanted to see.

Looking across the cleared construction site, and the side of the viaduct was clearly visible:

This is a view of what remains of the 1860s construction of Holborn Viaduct, and how the long approach to the bridge was built up in height.

At the top, there is a distnct layer which makes up the made ground under the street.

We then come to the core of the viaduct, with the edge of brick walls, which presumably run the width of the viaduct across the street, and in the lower half of the viaduct there are clearly defined brick arches.

Much of the side of the viaduct appears to have been skimmed and filled with concrete. I assume the whole of the viaduct has been filled, but it would be interesting to know whether there is any open space within the arches of the viaduct.

I also assume that the concrete skim and possible fill is of later date, and the brick columns and arches are from the 1860s build of Holborn Viaduct.

It is not often that you can see the hidden details of Victorian design and construction techniques, and the outline of the brick arches that support Holborn Viaduct will probably be soon covered again by the new building that will be built on the site, but they show the considerable construction work either side of the bridge, and which you are walking over as you walk along Holborn Viaduct, towards the bridge over Farringdon Street.

There has been a considerable amount of construction in Farringdon Street in the small section between Holborn Viaduct and Ludgate Circus in the last few years, the above example being just the latest, and I wanted to see what was happening at another, where the Hoop & Grapes pub was located:

The Hoop & Grapes has been closed for the last couple of years, when the buildings on either side of the pub were demolished.

The new building on the right of the pub is making good progress, and there will soon be more construction on the left, and until this is complete the left hand wall of the pub is shored up.

The building is Grade II listed and is of some age. According to the listing details, the building was part of a terrace, with the house being built around 1720 for a vintner, and converted to a public house in 1832.

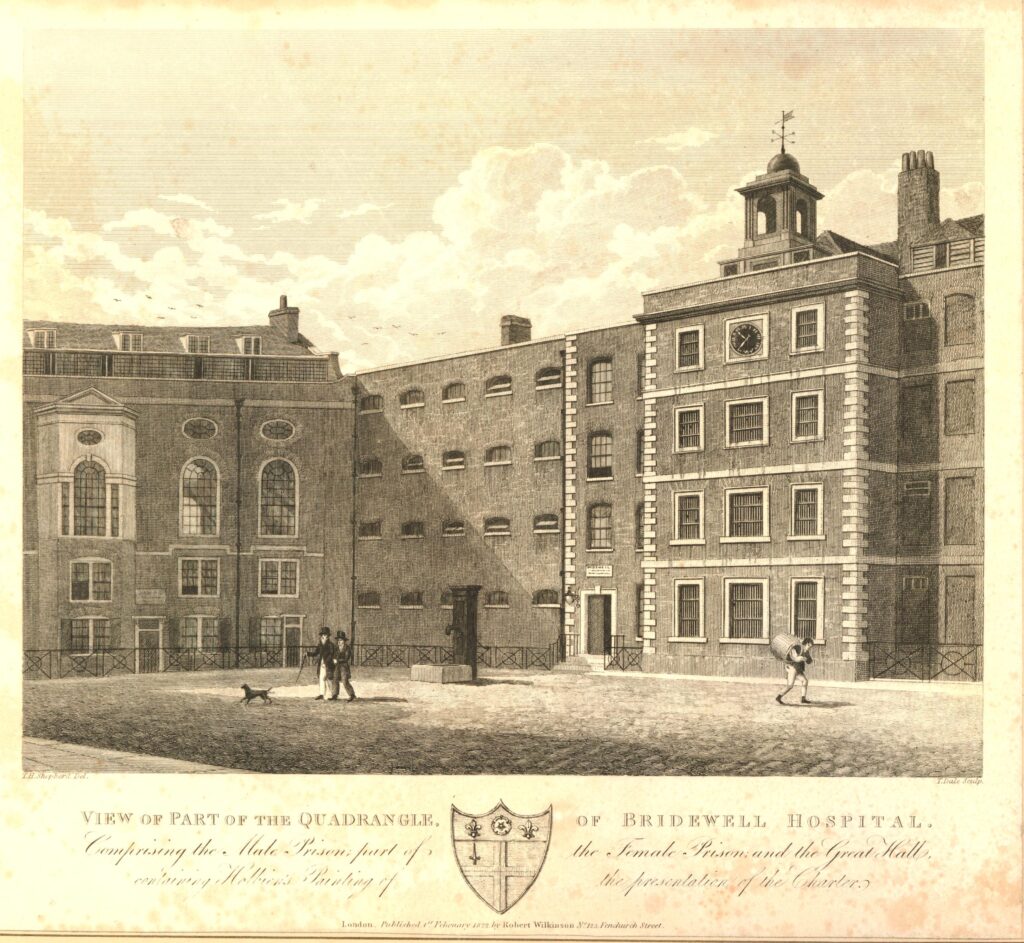

The listing also states that the “Basement has brick vaults thought to be part of 17th century warehousing vaults built in connection with the formation of the Fleet Canal. Built on part of the site of St. Bride’s Burial Ground.”

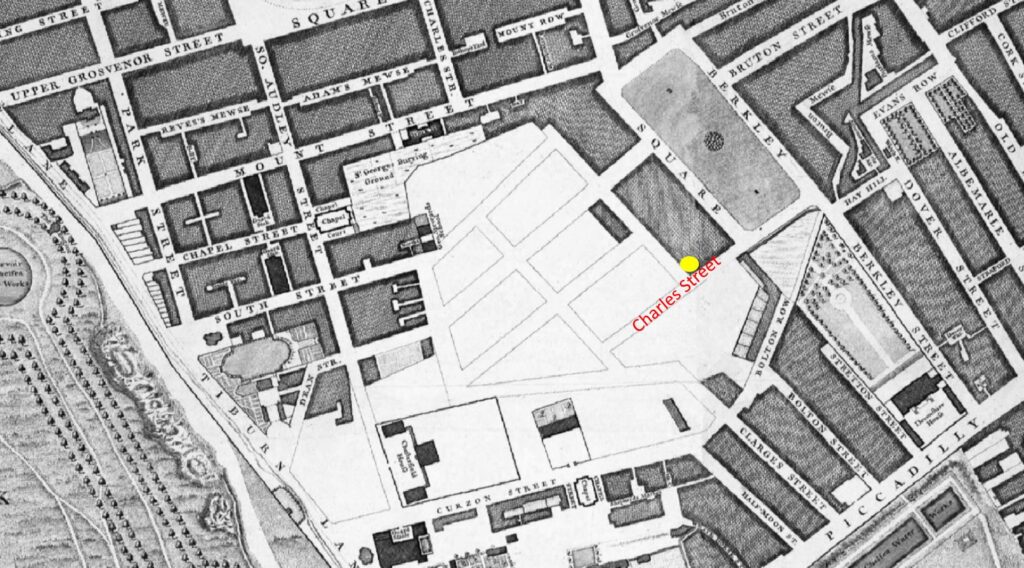

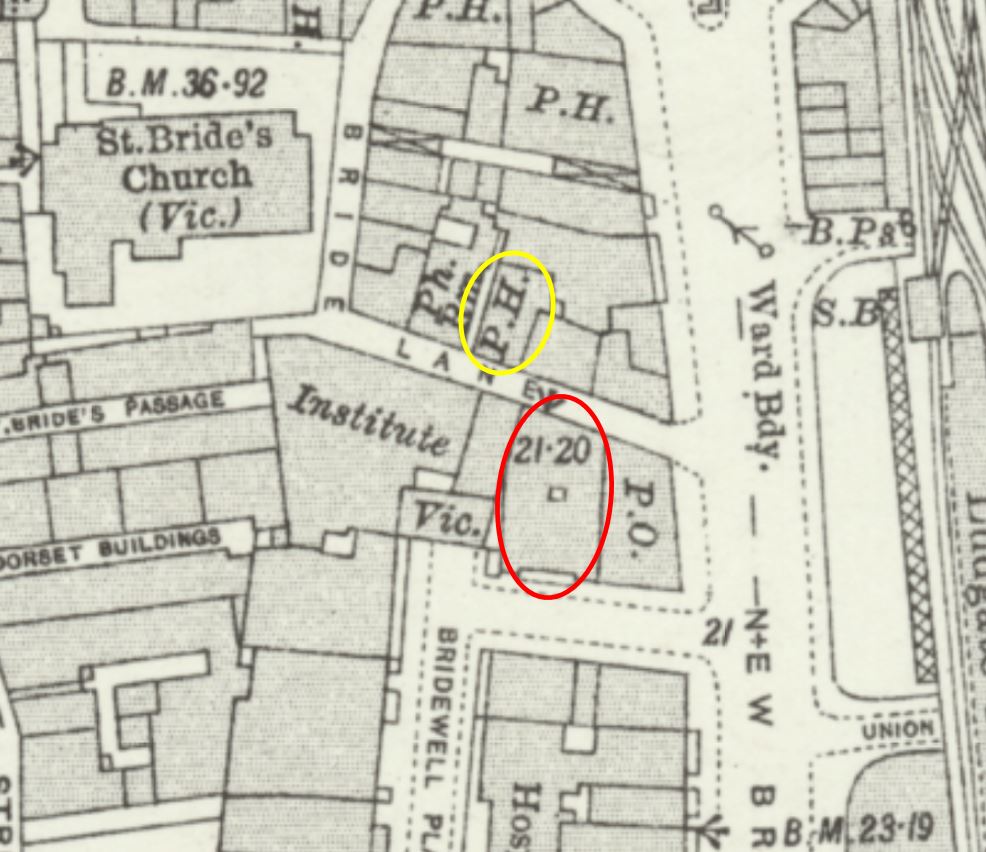

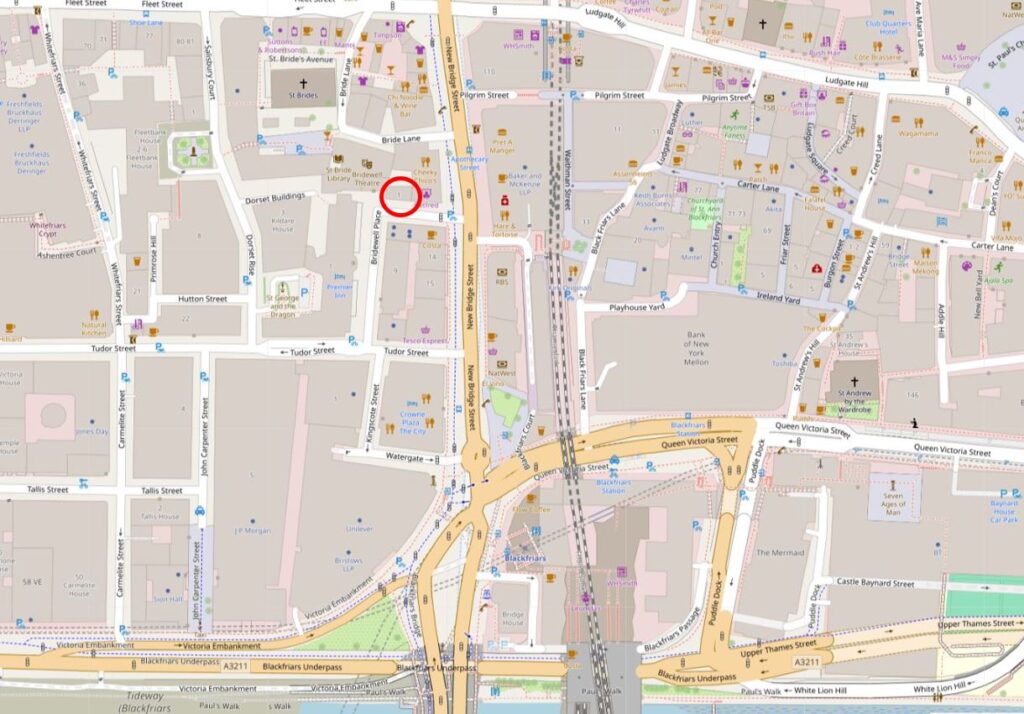

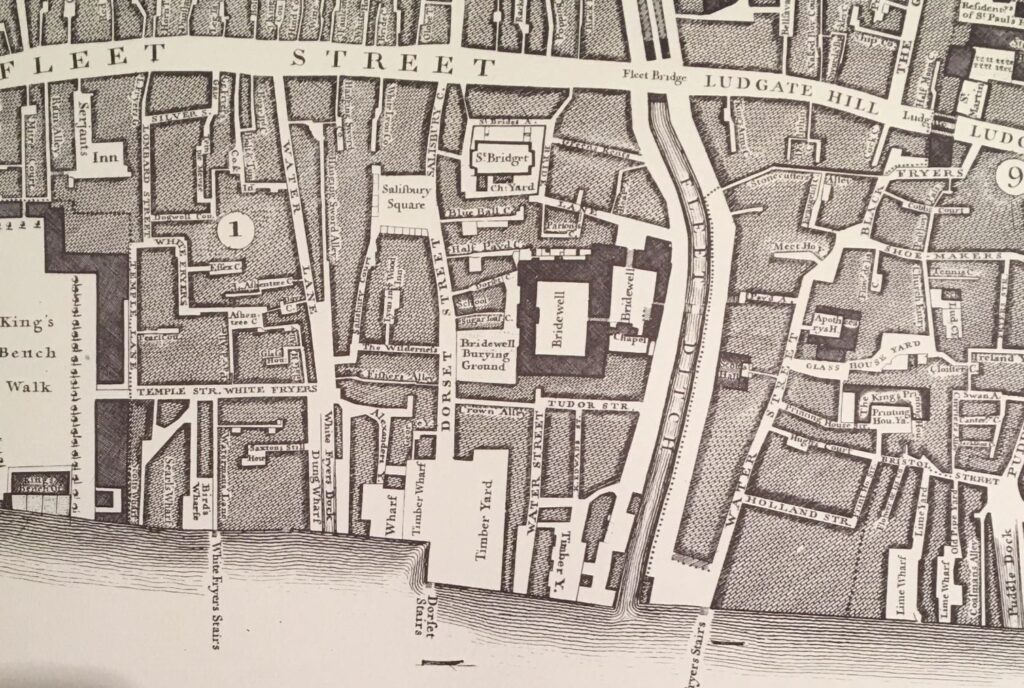

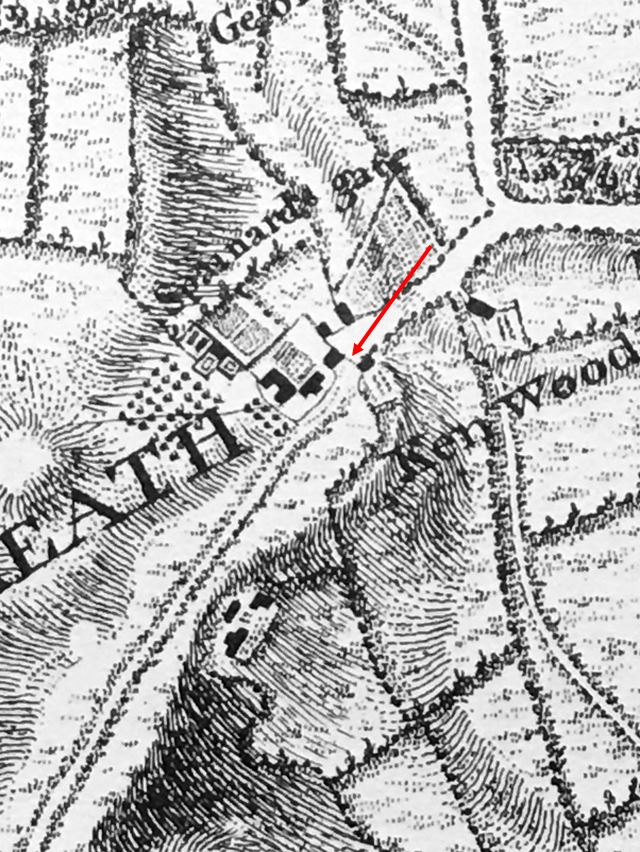

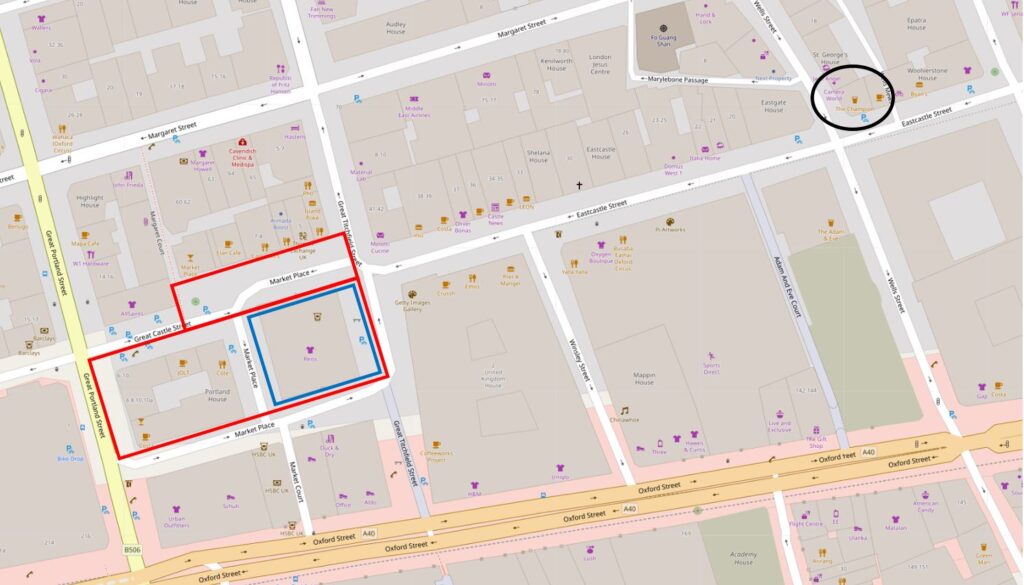

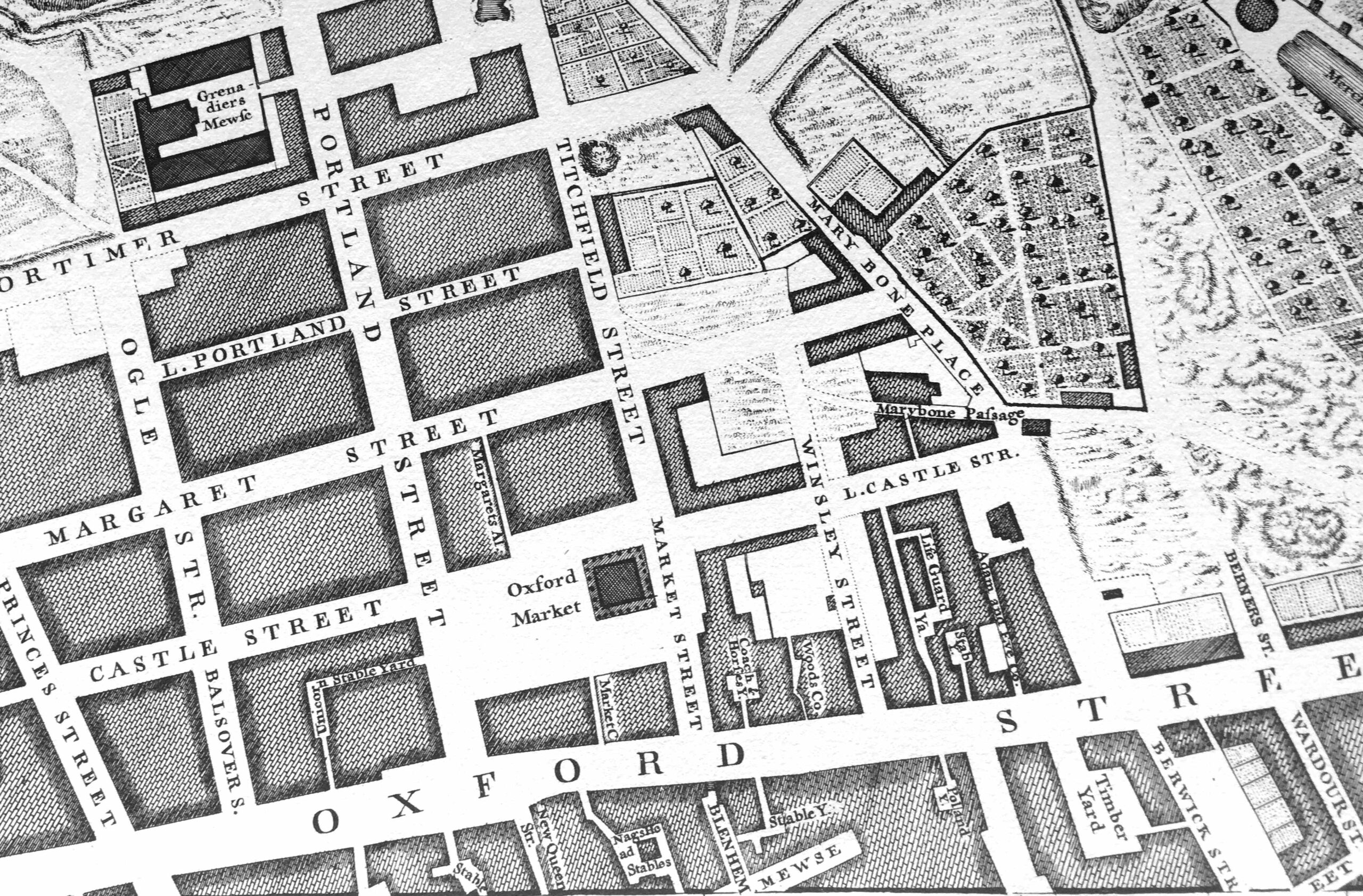

Rocque’s 1746 map still shows St. Bride’s burial ground (ringed in map extract below), although there is a space between the burial ground and Fleet Market, so the terrace which included the building that would become the Hoop & Grapes could have been within this small space, or perhaps to one side:

The Fleet Canal reference in the Historic England listing refers to when this stretch of the River Fleet was constrained within a channel, along which, and partly over, the Fleet Market developed.

Another view looking at the new developments and the old Hoop & Grapes pub, which has seen the area change beyond all recognition since the house was built:

I really struggle with some of these redevelopments.

London has always changed. Some of the terrace houses that survived to the 20th century along with the Hoop & Grapes were damaged during the war, and then demolished.

New officces were built surrounding the pub in the 1950s. These were in turn demolished in the 1990s, and it is these buildings which are being demolished for the new development.

Each iteration of development seems to get larger and more overpowering for buildings that survive, and based on the lifespan of the post-war developments on the site, the building currently being built, will be demolished in turn, in the 2060s / 2070s.

Again, it is good that buildings such as the pub survive, but they almost become a museum exhibit, stuck in a streetscape that they have no relationship with, and totally out of context.

I photographed the Hoop & Grapes in 2020, when I had a walk around all the City of London pubs:

I do not know whether the pub will reopen when redevelopment of the surrounding buildings has been completed.

The City of London Corporation seems to be making some efforts to retain City pubs, and they have announced that the Still and Star, Aldgate, St Brides Tavern, Blackfriars, the White Swan, Fetter Lane and the King’s Arms at 55 Old Broad Street / London Wall, will all be reopening in the coming years, however this often refers to the name being retained and the pub being relocated to a new structure within a new development.

There is no mention of the Hoop & Grapes.

A very short distance south along Farringdon Street, on the opposite side of the road is 5 Fleet Place, the cream coloured building that was completed in 2007:

In the above photo, you can just see a road sign with a white arrow on a blue background on the street at the corner of the building. Look through the square arch of the building to the left of the arrow sign, and there are three plaques. which tell of religious and political history:

Staring from the bottom is a stone that was laid on the 10th of May, 1872 at the new Congregational Memorial Hall and Library:

The stone states that the Memorial Hall was erected to commemorate “The Fidelity of Conscience shown by the Ejected Ministers of 1662”.

To understand what was being commemorated, we need to go back to the mid-16th century and the Act of Uniformity of 1558. This was passed in 1559 and established that the church should be unified around Anglicanism and worship should be according to the Book of Common Prayer.

This act was an attempt to address the conflict between Catholicism and Protestantism that had been simmering since the break from the Church of Rome by Henry VIII.

The act lasted until 1650 when it was repealed by the Rump Parliament established during the first year of the new Commonwealth of England, set up immediately after the English Civil War.

It was repealed to provide greater religious freedom for Puritans and non-conformists.

There was a strong religious independent and Puritan element to Parliamentary forces in the Civil War, and is why many churches had their decoration and statues damaged and destroyed by Parliamentary soldiers as these were seen as being a residual influence of the Church of Rome.

When Charles II was returned to the throne, there was pressure from the Church of England to unify the church around Anglican principles and the Book of Common Prayer.

The Act was brought back into law, and Ministers were forced to swear an oath that they would give “unfeigned assent and consent to all and everything contained and prescribed” in the Book of Common Prayer.

Many Puritan, Presbyterian and Independent ministers could not swear such an oath, and around 2,000 were forced out by the “Great Ejection” from the Church of England on St. Bartholomew’s Day, the 24th of August, 1662 – the event recorded by the stone.

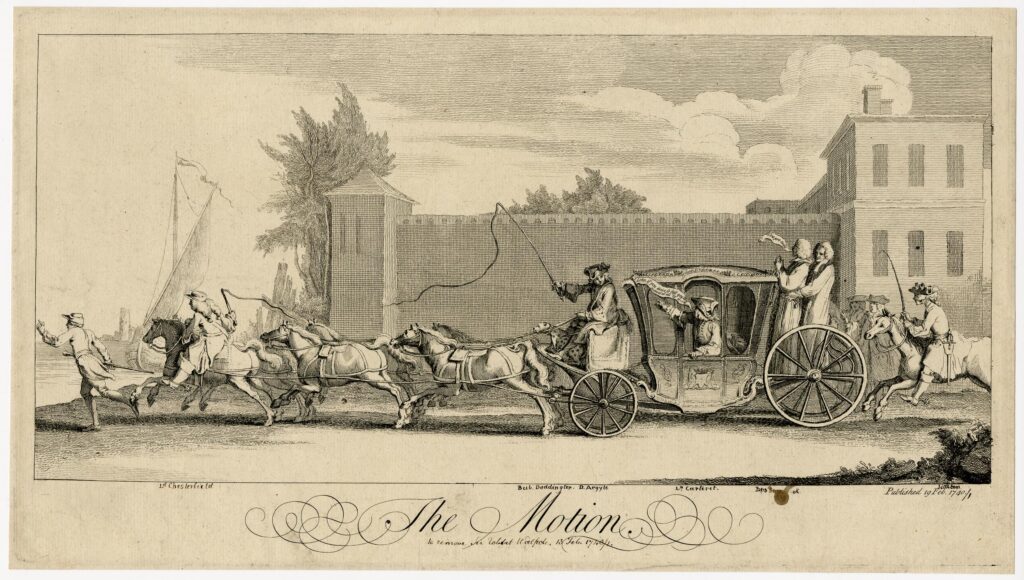

Title page from the pamphlet “‘The Farewell Sermons of the Late London Ministers'” showing 12 of the ejected ministers:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Newspaper reports of the ceremony to lay the foundation stone included the following which gives some background as to how the memorial hall was funded and the facilities within the building:

“The Act of Uniformity passed in the year 1662, had the effect of ejecting from their charges more that two thousand ministers who could not conscientiously subscribe to it. At a meeting of the Congregational Union, held at Birmingham in 1861, it was resolved to commemorate the event.

A conference was convened and held, at which it was decided that a bicentenary memorial fund should be raised, among the objects specified being the erection of new chapels, the extinction of chapel debts, and especially the erection of a Congregational Memorial Hall. A committee was appointed to carry the scheme into full effect, and at the next annual meeting it was reported that the total amount paid and promised in connection with this commemoration was nearly £250,000.

A site was found in Farringdon-street, which had formed part of the old Fleet Prison, and the ground was purchased at a cost of £23,000. The architect’s designs comprise a hall to hold from 1,200 to 1,500 people, a library, a board-room, and other offices. The whole is erected at a cost of not less than £30,000.”

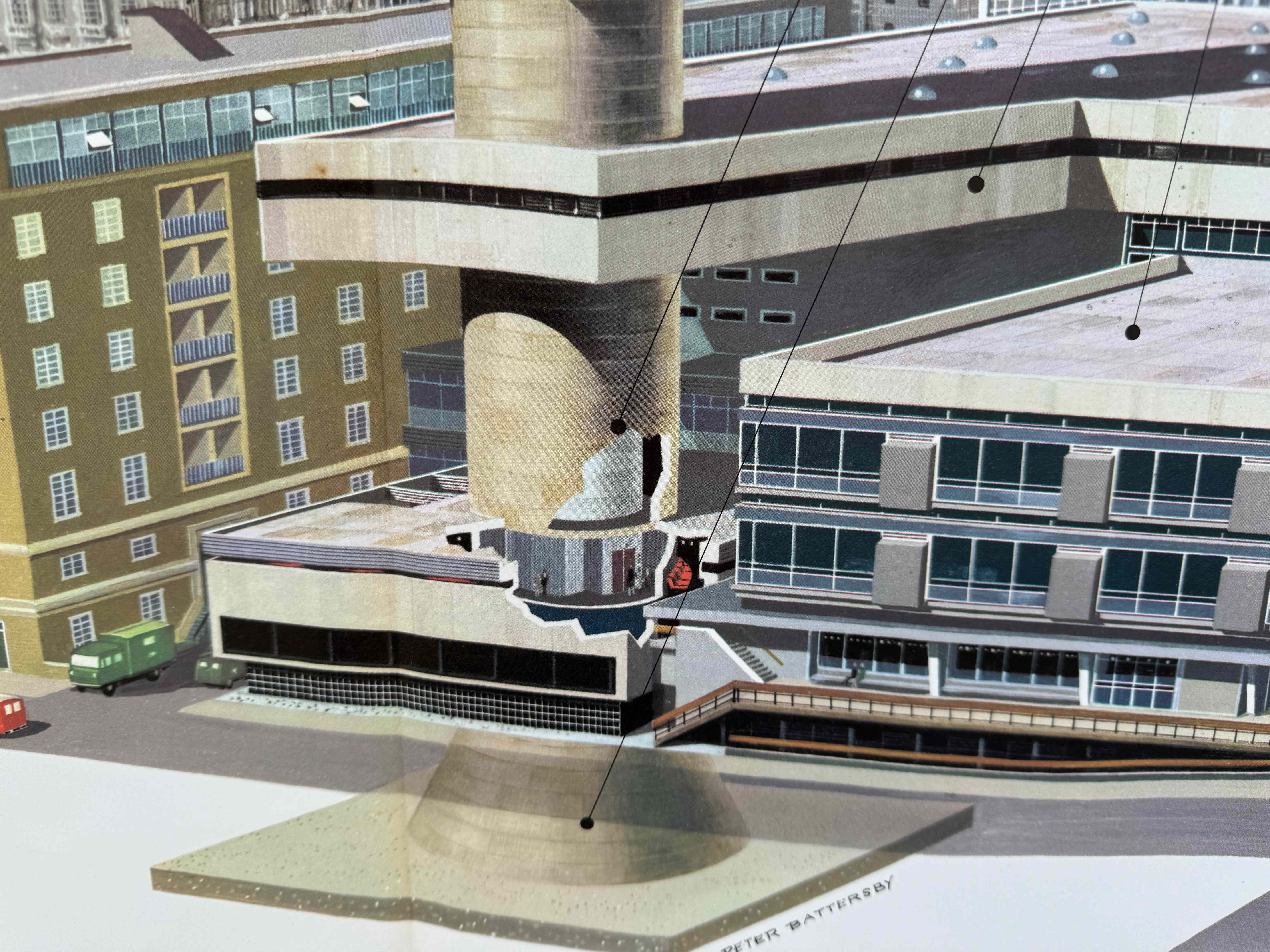

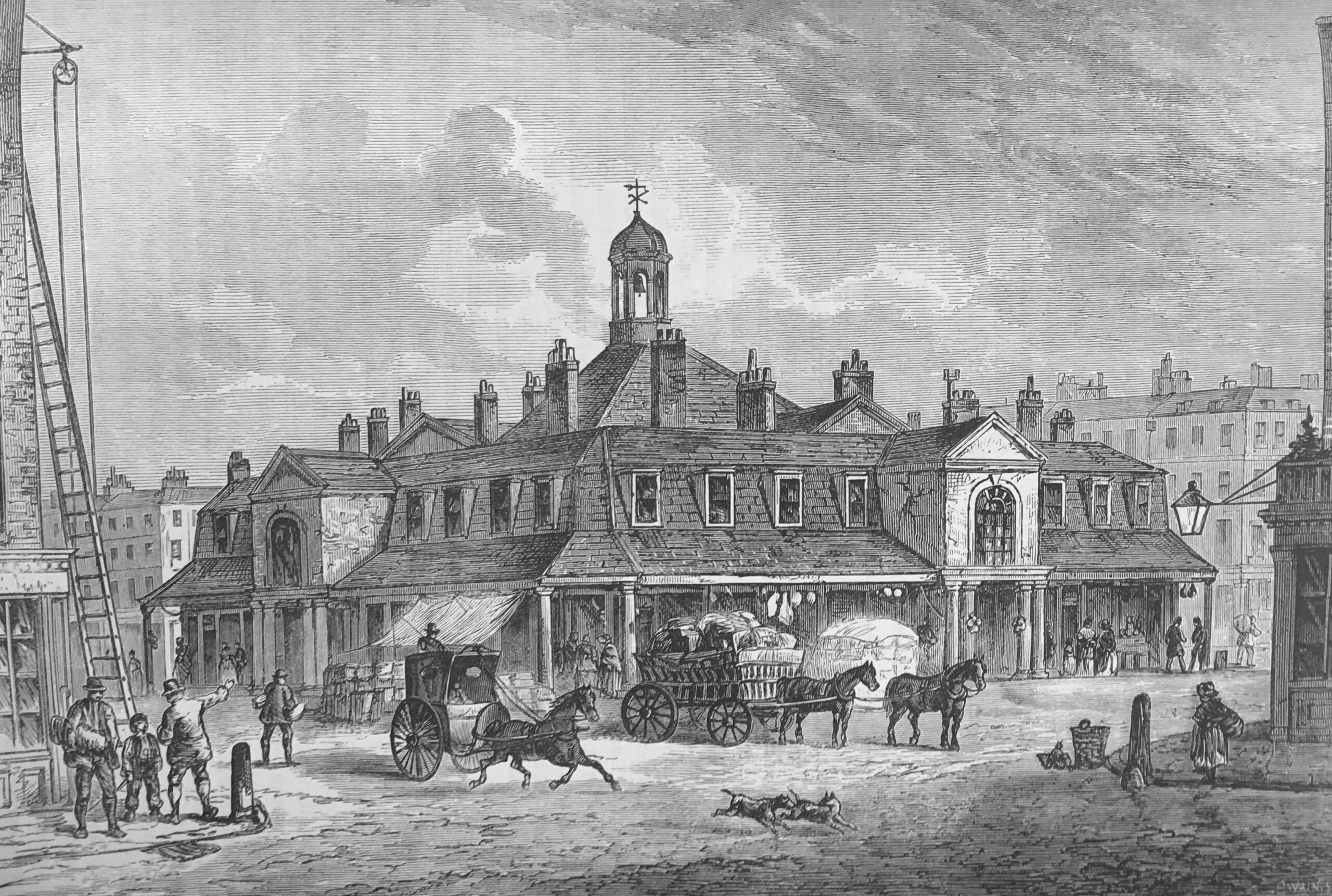

The Congregational Hall and Library as it appeared in the 1920s (the building with the large tower):

The library was a considerable resource of over 8,000 volumes and manuscripts covering dissenting religious history.

The library was moved to Manchester during the war, for safety, and also because the Government requisitioned the building between 1940 and 1950 for war purposes.

The library returned in 1957, however ten years later, the collection had to be moved out again as the site was being redeveloped, which brings us to the second plaque:

Around 100 years after completion, maintenance of a large Victorian building was difficult and expensive, so the Congregational Memorial Hall Trust decided to have the site redeveloped with a new office block on site, along with space for the library and for meetings.

The above foundation stone is from this new building – Caroone House.

The library though did not return to the new building. It had been moved to 14 Gordon Square in advance of the redevelopment, and was housed with and administered by Dr. Williams’s Library, another library of religious dissenting books and manuscripts.

The library had to move out of Gordon Square a couple of years ago due to the potential costs of the redevelopment of the site, and the library is now housed at Westminster College, Cambridge, a theological collection that brings together Congregational and Presbyterian college traditions.

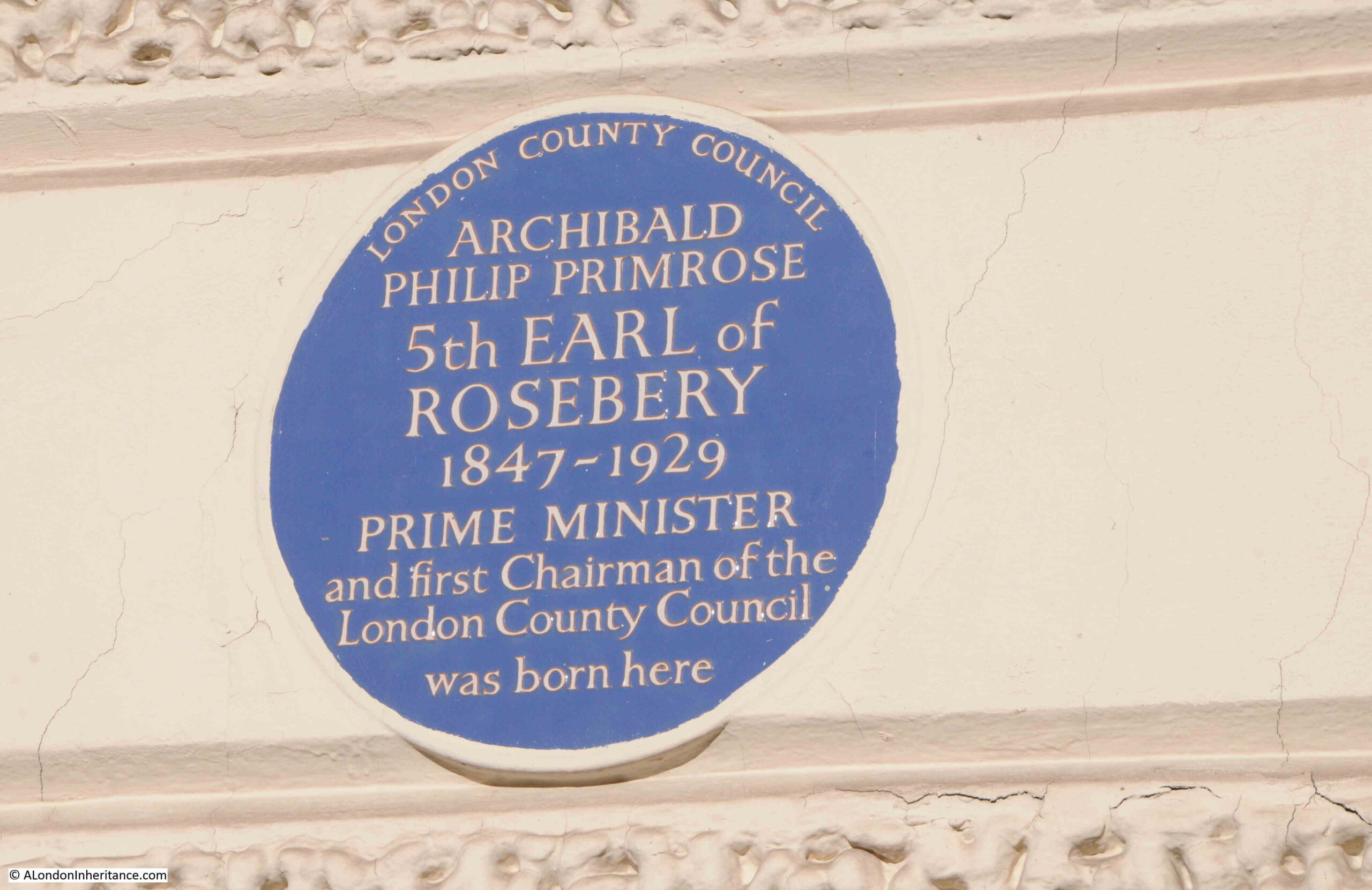

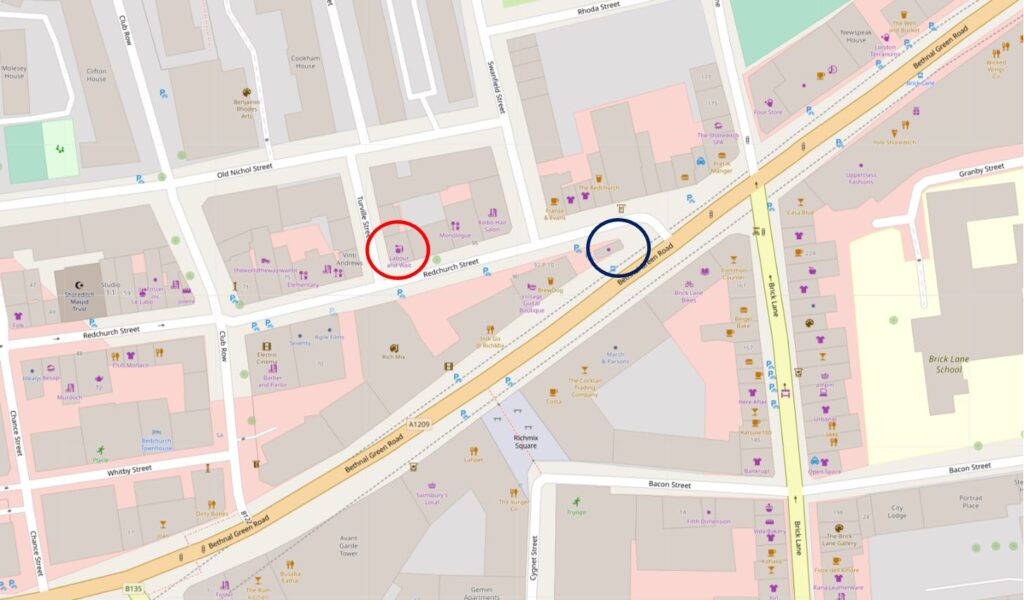

And now for the third plaque. It is not often that one of my posts has a very topical subject, but for this week’s post, in 1900, the Congregational Memorial Hall was the site of the founding of the Labour Party:

Rather than a northern industrial town, the meeting that resulted in the founding of the Labour Party was held in the Congregational Memorial Hall, in Farringdon Street on the 27th of February, 1900.

The meeting was the inaugural meeting of the Labour Representation Committee and the purpose of the meeting, which had been arranged by the Trades Union Congress, was to agree on how the various strands of the Labour movement could be brought together into a single party.

Up until the 1900 meeting, the interests of labour had been represented by the Trades Union Congress, the Independent Labour Party and the Social Democratic Federation, who all attended the meeting in Farringdon Street.

The Cooperative Movement had been invited but did not attend as their aim was to maintain a politically neutral approach.

130 delegates met in the library of the Congregational Hall, and the following paragraph from the end of a report on the meeting in the London Daily News gives an indication of the approach of the new unified Labour Party:

“The speeches for the most part were couched in a spirit of broad toleration. Mr. Burns and Mr. Harnes, and Mr. Steadman and Mr. Tillett, all protested against the spirit of narrow sectarianism which has prevailed so largely hitherto.

And Mr. Hardie and Mr. Burgess, from the Independent Labour Party also took the same line, and strongly condemned a proposal that a Labour Party should be organised upon the basis of ‘recognising the existence of a class war’, which got defeated by the adoption of an amending resolution.”

Caroone House was demolished in 2004, so that the office block we see today could be built, and which was completed in 2007. The two foundation stones and the plaque recording the founding of Labour were reinstalled.

A very short walk along part of Farringdon Street, where we can see part of the viaduct constructed by the Victorians to create a wider and higher bridge over what was the route of the River Fleet, a 300 year old house that once looked onto the river and that once housed a pub, and hopefully will do so in the future, as it is surrounded by much larger steel and glass office blocks, and the site of a hall, built to commemorate a religious schism in the 17th century, and the founding of the Labour Party at the very start of the 20th century.

Another example of just how much diverse history can be found during a short walk along a City street.

The next time I write about Farringdon Street, I hope that the Hoop & Grapes will be open again as a traditional London pub, rather than what seems to happen to so many pubs where development takes place – a reimagined pub.

Despite the appearance of Farringdon Street today, it is a very historic street, and the Fleet Prison which was on the site of the Congregational Memorial Hall will be the subject of a future post.