One of my father’s 1980s photos was of the war memorial in Cyprus Street, Bethnal Green:

Forty years later, I went back to take a 2023 photograph:

There are a couple of interesting changes to the overall memorial. The small memorial below the main First World War memorial is for the Second World War, presumably also for those from the street who died during that war. In my 2023 photo, this plaque has had a name added since the 1980s.

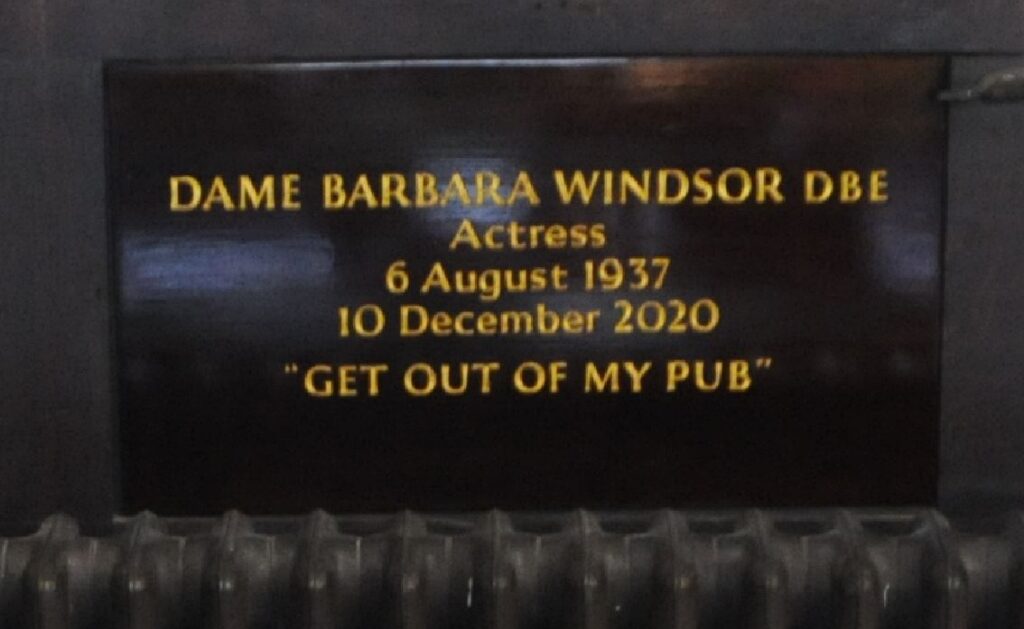

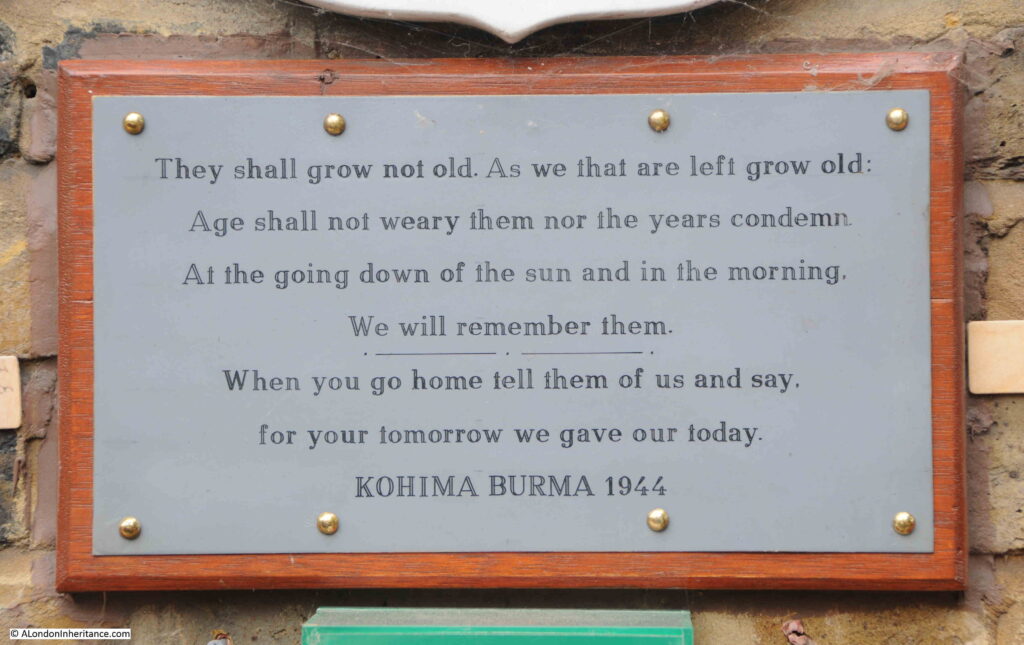

Below that there is a new plaque which has been added:

And below the above plaque is one of the ceramic poppies from the 2014 display in the moat of the Tower of London to commemorate the start of the First World War.

The memorial in Cyprus Street:

The memorial is not in its original location. I have read a number of slightly different stories online about the fate of the original memorial, and move to the current location. I will use the following quote from the publication “Not forgotten, A review of London’s War Memorials”, published by the Planning and Housing Committee of the London Assembly in 2009:

“The memorial was originally on the wall between numbers 45 and 47

but in the 1960s, when one end of the street was redeveloped for a

new housing estate, the main memorial was broken while it was being

removed. The community rescued the plaques and for a while the

fragments lay around the local pub, the Duke of Wellington. After a

number of years the community took the opportunity to use the

refurbishment of their street to make a collection to pay for a replica

of the original memorial to be made at a local stonemasons and got

permission from the housing association to relocate it to where it now

stands.”

The London Assembly document states that the current memorial is a replica of the original. I have read other accounts that state it was repaired, however if that is true, then it must have been a very good repair.

The problem with determining which sources are correct is difficult as even in the London Assembly document there is an error. It states that “The original Cyprus Street memorial was erected at the end of 1918 to commemorate the residents of the street who died in the First World War”, however I have found a number of reports from newspapers of the time which state that the memorial was unveiled in 1920, perhaps there was a two year delay between erecting the memorial and unveiling, however I doubt it.

It is always difficult to be 100% confident in many statements that are recorded as facts.

What ever the truth of the memorial, nothing can detract from what it represents – the impact of war on one small London street.

The plaque was unveiled on Saturday the 5th of June, 1920, and the East London Observer had a report of the unveiling in the following Saturday’s issue:

“A BETHNAL GREEN WAR MEMORIAL – In Memory of Cyprus Street Men. A touching ceremony took place last Saturday afternoon at Cyprus Street, Bethnal Green, where there was unveiled and dedicated a War Memorial Tablet to the men of the street, which is in the parish of St. James-the-Less, Bethnal Green, who had fallen in the Great War. The memorial was raised by the members of the Duke of Wellington’s Discharged and Demobilised Solders’ Benefits Club, of which Mr. Keymer is the Chairman.

The St. James Brass Band opened the service and after hymns, prayers and lessons, the Rev. J.P.R. Rees-Jones, Vicar of the parish, unveiled and dedicated the memorial tablet.

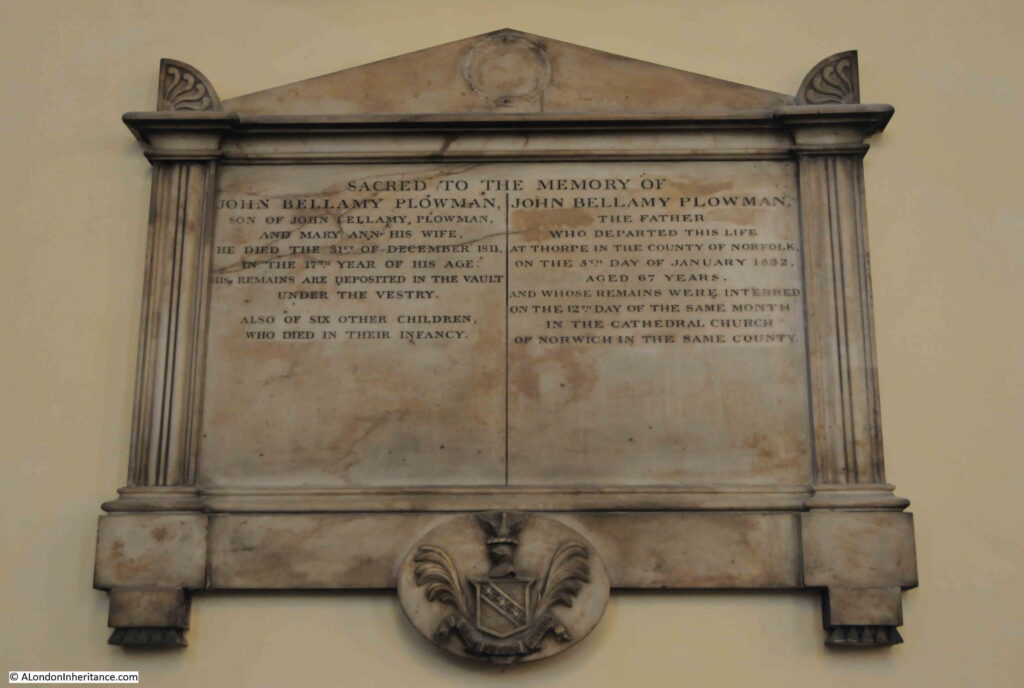

The tablet is of white marble with imperishable lead lettering, with a beautiful scroll, the work being executed by Messrs. B. Levy and Sons, ltd. monumental masons, Brady Street, Whitechapel, a firm which has gained much notoriety by virtue of the excellence of workmanship and design, and the tablet was greatly admired by all who attended the interesting ceremony.

The Vicar gave a short but inspiring address, and after an anthem, “What are these arrayed in white robes”, given by the St. James’s choir, and the hymn “Lead Kindly Light”, the blessing was pronounced, followed by the “Last Post”, the “Dead March” and “Reveille”. There was a large assembly, and for once in a way Bethnal Greeners stopped to think of something else than their every day cares.”

The names on the memorial joined the names on thousands of other war memorial that were erected after the First World War, and the problem with war memorial is that the sheer number of names hides that fact that these were all individuals, and I have tried to find out about some of those listed.

In the 1911 census (the nearest I can get to the First World War for a full list of those living in Cyprus Street), there were 827 people recorded as living in the street.

Given that 26 people are listed as having died during the First World War, assuming roughly the same number of people were living in the street as in 1911, then 3% of the street’s residents would die in the war.

Whilst this may initially seem a relatively low number, many families at the time would have large numbers of children, so as a percentage of adults in the street, it was much higher than 3%.

When comparing the names on the memorial, I was surprised that a relatively high number were not listed in the 1911 census, implying that they were not then living in the street, I did wonder if those commemorated were from surrounding streets, however the memorial clearly states that they are the men of Cyprus Street.

I did find a number listed in 1911, and the census records provide a more rounded view of the names on the monument, for example:

- A. Gadd – The Gadd family lived at number 51 Cyprus Street. There were two Alfred Gadd’s in the family. The father who was 45 in 1911 and the eldest son who was 18. The father was a Cabinet Maker, and the son was Linen Collar Sorter. I suspect that it was the son who died in the war, as the father would have been approaching 50 by 1914. As well as the father and oldest son, there was the wife Elizabeth (44), daughters Rosalie (20, a Brush Hair Sorter) and Elizabeth (16, a Dressmaker)

- J. Goodwin – The Goodwin family lived at number 91 Cyprus Street. There were two John Goodwin’s in the family, however the eldest son John was only 6 in 1911, so it is the father, who was aged 27 and listed as a Butcher who died in the war. As well as the father and oldest son, there was the wife Elisa (26) and children Robert (5), Charles (4), daughter Grace (2) and youngest son Sidney (0, born in 1911)

- T. Hamblin – The Hamblin family lived at number 59 Cyprus Street. T. Hamblin refers to Thomas Hamblin who was 32 in 1911 and listed as a Dock Labourer. He lived in the house with his wife Elizabeth (30 and a Tailoress). No children are recorded.

- W. J. Gardner – There was no W. J. listed in the 1911 census, but there was a William Gardner at number 64, so I assume he may have left his middle name out of the census. William Gardner was 27 and a Builders Labourer. He lived in number 64 with his wife Florence (25 and a Skirt Machinist) and daughter Florence who was 4.

Just four out of the twenty-six who are listed on the memorial, but it reminds us that these were individuals with jobs and families, who would have impacted by their loss for very many years to come. The youngest child, Sydney Goodwin would hardly have known his father and Sydney could have lived to the end of the twentieth century.

It is also interesting to compare the number of names on the memorials for the First and the Second World Wars, with far less from the street who died in the Second World War.

This comparison shows the absolutely appalling death rates from the trench warfare of the First World War.

The reference on the memorial to the Duke of Wellington’s Discharged And Demobilised Soldiers And Sailors Benevolent Club refers to the Duke of Wellington pub in Cyprus Street. The pub was built around 1850 as part of the development of Cyprus Street and surrounding streets. The pub closed in 2005, but today still very clearly retains the features of a pub, including a pub sign:

The Duke of Wellington, like many other pubs in the working class areas of London, had a tradition of hosting benefit and loan societies.

In 1911 there was a large advert for the Duke of Wellington in the Eastern Argus and Borough of Hackney Times headed “Important Notice”. It was one of the very many adverts that publicans would place in the local newspapers when they took over a pub. The advert would tell potential customers that all classes would receive a warm welcome, that only the very best beers and spirits would be served, and the advert of the Duke of Wellington also included that:

“The United Brothers Benefit Society meets here every alternate Tuesday evening and the Duke of Wellington Loan and Investment Society (which has been established for over 20 years) every Saturday evening. New members to both societies respectfully invited and heartily welcomed.”

It was hosting societies such as these, as well as the very many clubs and societies involved with sports and games that put these 19th century pubs at the heart of the communities that developed around them.

The pub, as well as much of the original Cyprus Street terrace houses are Grade II listed.

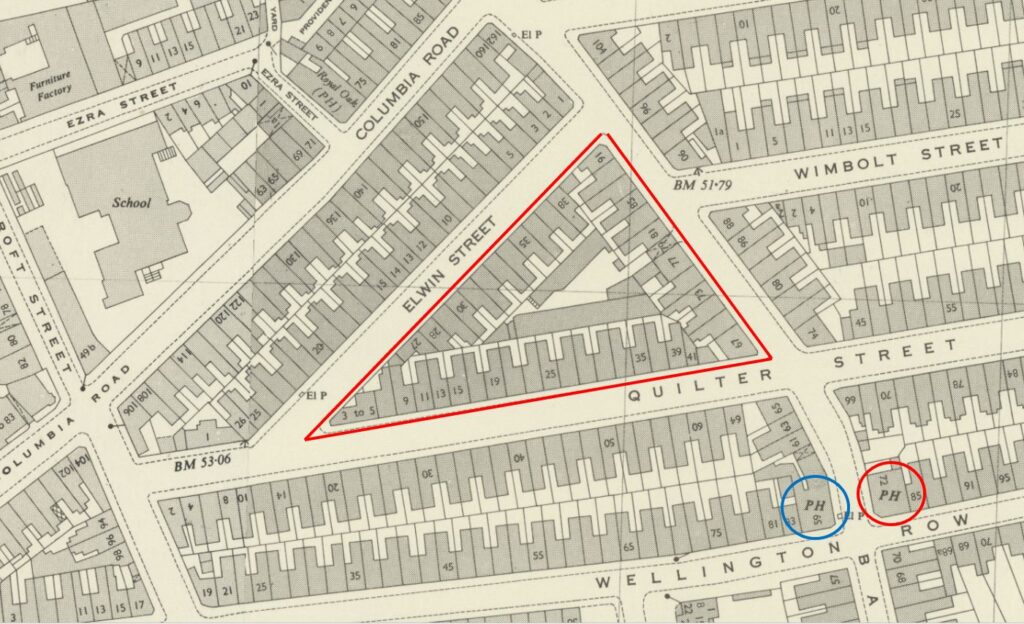

A chunk of the western part of Cyprus Street was badly damaged during the Second World War and the Cyprus Street Estate was built across the area that was damaged. This has effectively separated two parts of the original street.

In the following map, the red oval shows where Cyprus Street has been separated by the new estate, with a short stub of the street to the left, and the main section of the street to the right ( © OpenStreetMap contributors ):

The new estate can be seen just to the west of the old pub:

Cyprus Street is fascinating, not just for the war memorial, and architecture of the terraces, but also the way they are decorated, with many of the houses having a brightly painted front door and window shutters:

View along the main surviving section of the street:

Cyprus Street is identical to many other mid 19th century streets that appeared as Bethnal Green was developed, what has made it special is the war memorial and the retention of the majority of the original terrace houses.

As indicated by the Duke of Wellington’s Benevolent Club that erected the memorial, the pub must have played an important part in the community that lived along the street.

There were so many pubs in Bethnal Green (as there was across much of London), and in Bethnal Green the majority have closed, with many being demolished or converted into flats.

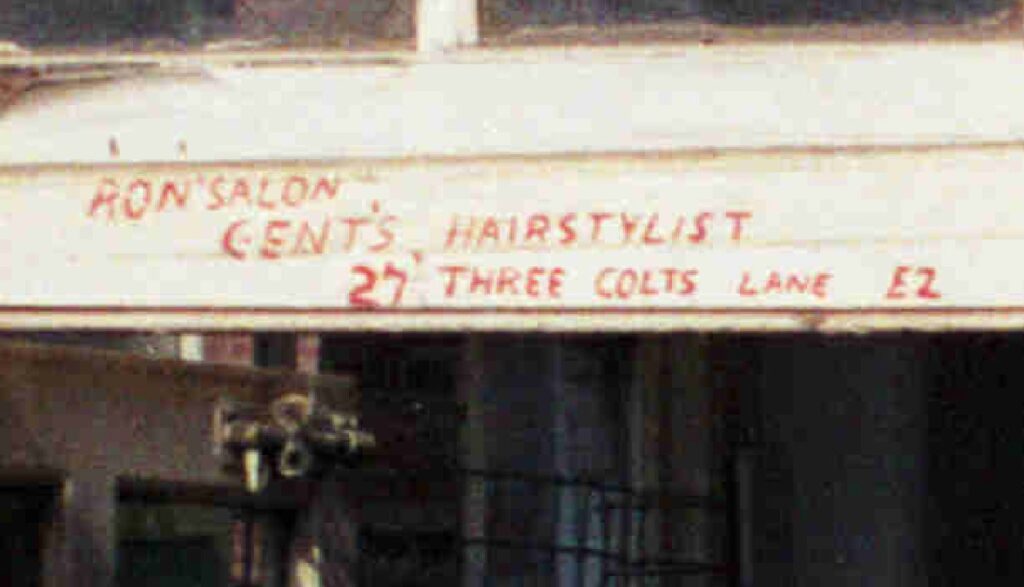

As I was walking to Cyprus Street, along Bonner Street, I saw another old pub just after the junction with Cyprus Street.

This is the Bishop Bonner, on the corner of Bonner Street and Royston Street:

Another 19th century pub, which finally closed in 1997. The first floor appears to be flats, however the ground floor looks rather derelict. It would be interesting to look in and see if any of the remaining bar furniture survives.

Name sign on the corner of the pub:

Always interesting to think of the thousands who have walked through these doors, when the pub was the hub of the local community for well over 100 years:

Whilst so many of London’s pubs disappear or are converted, the memorial in Cyprus Street remembers not just the residents of the street who died in the First and Second World Wars, but also remembers the community that was in the street at the time, that enabled the memorial to be created and maintained during the following decades.