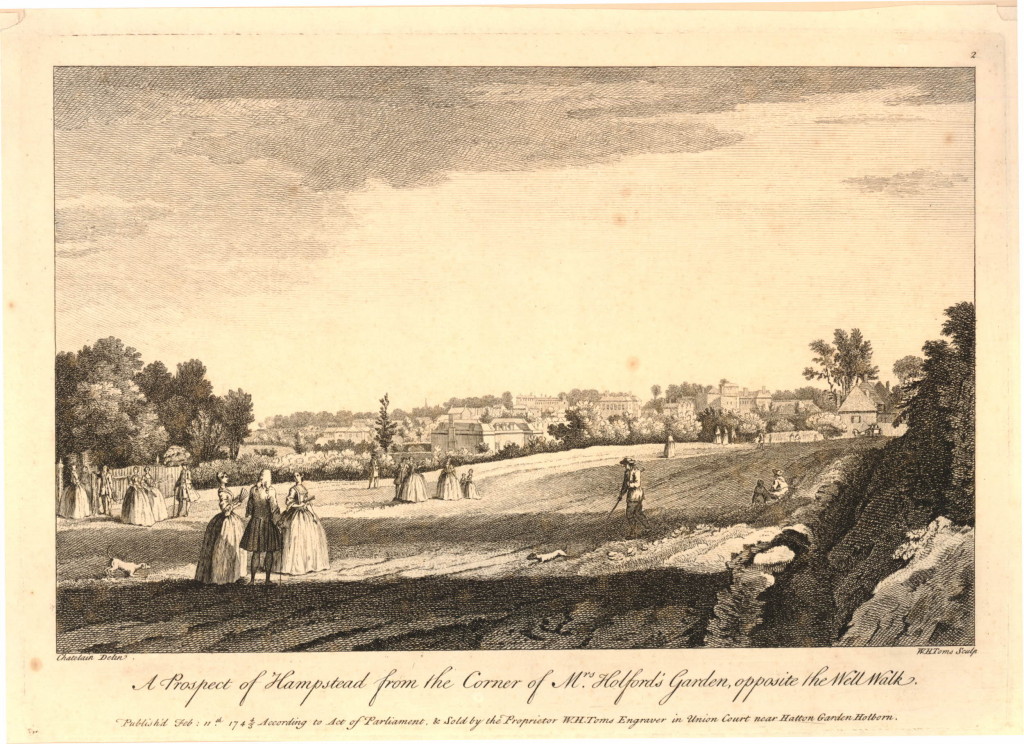

The Vale of Health is a rather unique place. To the north of Hampstead, the Vale of Health is a small enclave, surrounded on all sides by the heath and accessible only via a single road.

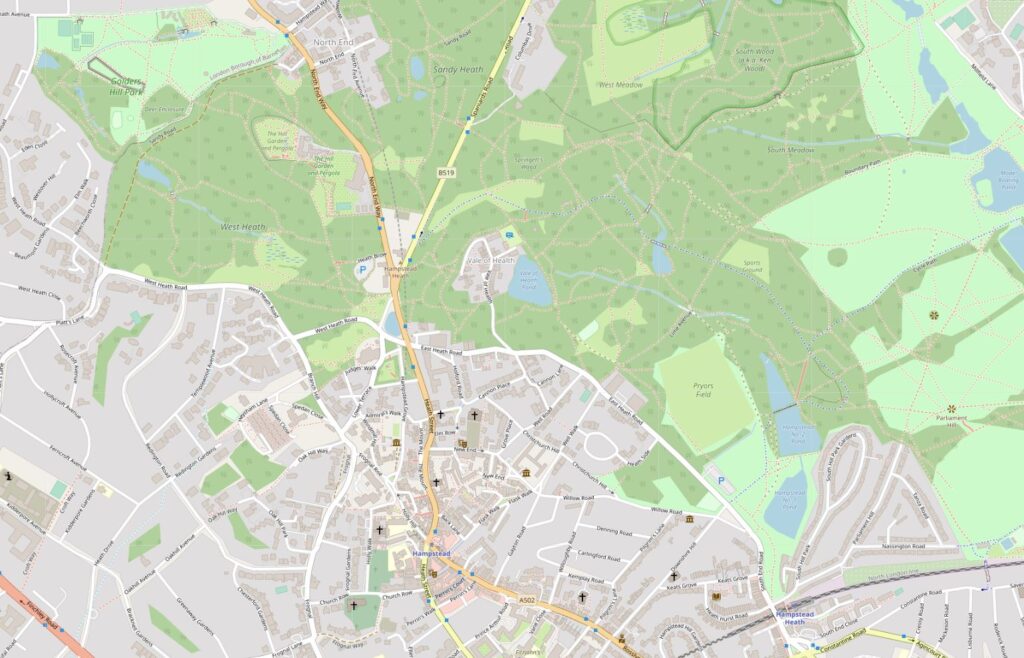

In the following map, the Vale of Health is in the centre of the map, with the blue for a pond on the eastern edge, surrounded by the green of Hampstead Heath, with a single road leading down from East Heath Road (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

I had a recent visit to the Vale of Health, the reason being was to track down the location of some photos my father had taken of the general area, and a couple of photos showing the lost Vale of Health Hotel.

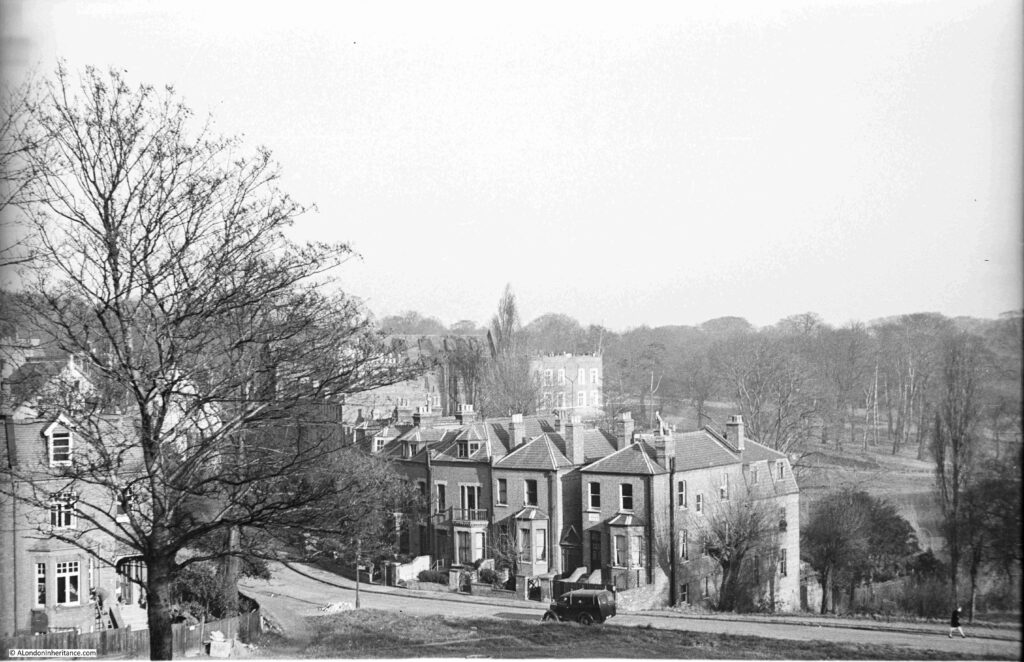

The first photo was a general view from the higher ground on the left, as you arrive on the single road that leads into the Vale of Health:

Although my father’s photos were taken in winter and mine in summer, so in my photos the trees are in leaf, the area is far more wooded today than it was, and the higher viewpoint for my father’s photo is today in among the trees and bushes with no clear view, so my comparison photo was slightly lower down, however the first houses along the road into the Vale of Health can still be seen:

For his second photo from the same spot, may father turned a little to the left. Much the same view, however a large house on the left of the street comes into view.

Again showing how much more overgrown this area is today, in the following photo the house is still there, but almost completely hidden by tree growth.

The Vale of Health is a really unusual place. A single access road leads down into a cluster of houses, with a large pond to the east, and the whole place surrounded by the rest of Hampstead Heath.

The pond is a clue as to why the Vale of Health developed. Originally the area occupied by the Vale of Health was wet and marshy. The springs that pop up around the heath fed into this hollow of land. The area was originally called Hatches or Hatchett’s Bottom, and was also referred to as Gangmoor.

The history of the area really starts with the City of London’s insatiable thirst for clean water. In the 16th century, three reservoirs had been built on the heath to provide water for London, however demand kept growing as the population expanded.

in 1692 the Hampstead Water Company was formed and the Corporation of the City of London granted the company leases on the Hampstead Heath reservoirs.

Demand exceeded the capacity of these reservoirs, so in 1777 the Hampstead Water Company drained the marshy area that was Hatchett’s Bottom and formed a new pond to store and supply water for the City. During the 19th century the Hampstead ponds continued to supply water to the City, but by the mid 19th century, water was only used for non-domestic purposes as the quality was rather poor, described as “somewhat disagreeable to the taste and small and was rather turbid; the sediment deposited was considerable, and contained numerous living organic productions”.

The way that land was given over to ownership and house building on Hamsptead Heath was rather complicated. Long before the heath had the protection it does today, it was open for encroachment and squatting, and frequently those encroaching on the heath, could stay providing they paid a fee to the Lord of the Manor.

Applications for the use of “waste land” were made to the Manor and if approved these were allocated on the basis of a “copyholder” where if the person who was allocated the land died, or sold the land, the person inheriting or buying the land had to pay a “fine” to the Lord of the Manor.

One of the early allocations of land, around 1770, was to a Samuel Hatch, which could be why the area was originally named Hatches or Hatchett’s Bottom.

After the new reservoir or pond was constructed in 1777, more applications for grant of waste land were made. Three cottages for the parish poor of Hampstead were built – the choice of area aware from Hamsptead possibly because the land was cheap and Hatchett’s Bottom was not yet an area where the wealthy aspired to live.

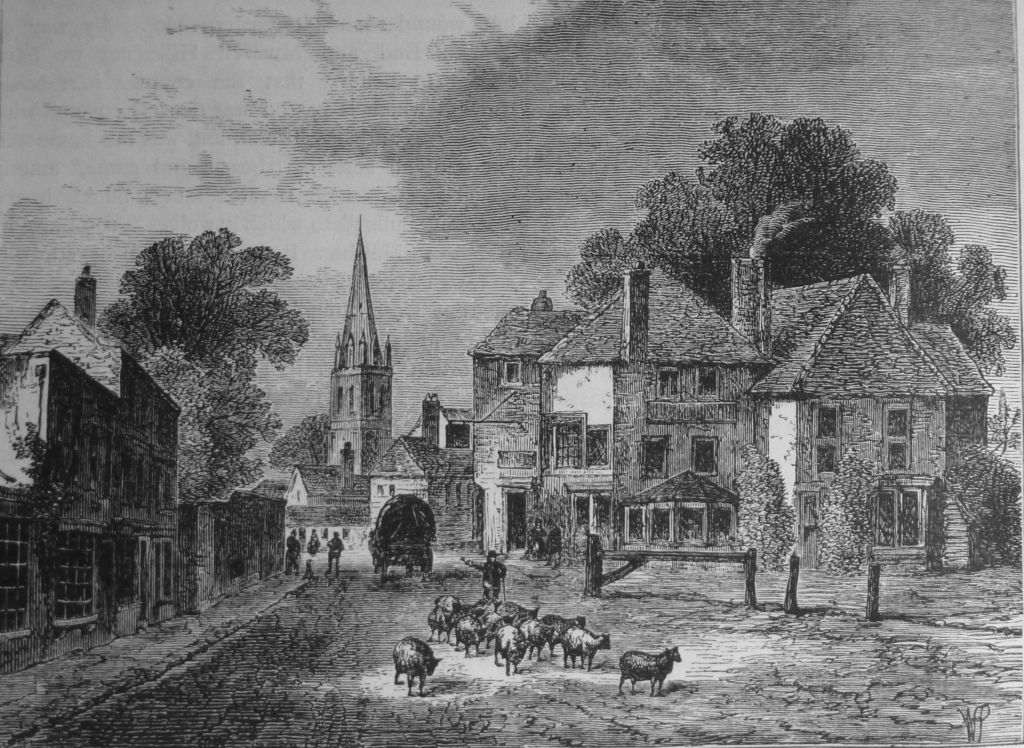

Houses continued to be built, and the area started to change into a desirable residential location. Surrounded by the heath, away from the noise and traffic of Hamsptead, Hatchett’s Bottom was starting to be a desirable location, however the name was probably associated with the marshy ground before being drained for the pond, and the location for parish poor houses so perhaps a new name was required.

The name Vale of Health starts to appear at the start of the 19th century.

There are many theories as to the source of the name, however it is probably simply down to a new name to differentiate the place from earlier conditions and usage.

Although the Vale of Health started to be used from around 1801 onward, the name Hatchett’s Bottom would still be used for several decades after.

Houses continued to be built in the Vale of Health, and the Hampstead Heath location meant that the Vale of Health attracted those who left the city on weekends and Bank Holidays to find somewhere for fresh air and entertainment, and it was the location of one of these places that I went looking for next.

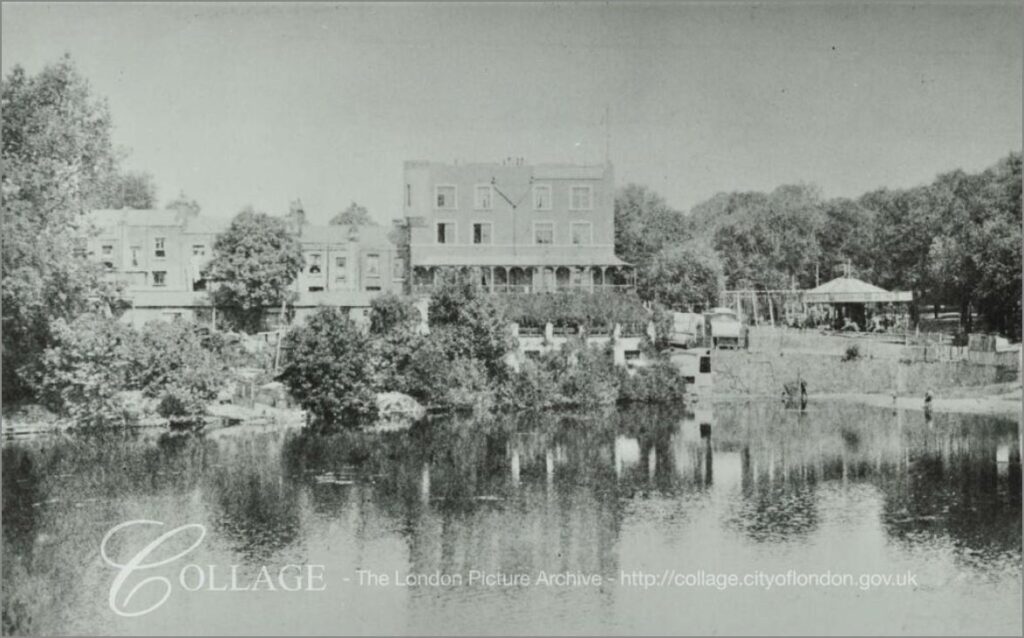

The following photo is my father’s photo of the Vale of Health Hotel. A large 4 storey building facing onto the pond. The view is across an area used as a fairground, and for the storage of fairground rides when not in use. The wooden frame nearest the camera has the words “dodgem cars” just above the top of the fence.

Roughly the same view today. I should have been a little further back, but this would have taken me into the trees and bushes.

In the 2020 photo, there is a high wooden fence blocking off the area that was used for fairground storage. The Vale of Health Hotel has been replaced by a high block of flats. The terrace of houses on the right are the same in both photos.

The Vale of Health was a focal point for summer weekends and Bank Holidays when thousands of Londoners would stream up to the heath to escape the city. The hotel offered rooms, bars, food, and verandas overlooking the pond. The area behind the hotel was used as a fairground. The Era on the 17th April 1909 had a small article about the fair:

“In the Vale of Health: Harry Cox, the local showman, proudly boasts that he never exhibits his show concerns away from the Heath. By the side of the Vale Waters you will find him ready to entertain you. Here you will see steam roundabouts, boats, swings, shooters and variety stalls. Harry Cox, Vale of Health Perpetual Pleasure Fair is the great central constellation around which many lesser lights live and shine”.

The following article from the Hampstead and Highgate Express reviewing the April 1888 Bank Holiday Monday on the heath provides a good impression of what it must have been like, and what went on across Hampstead Heath and in the Vale of Health:

“BANK HOLIDAY ON HAMPSTEAD HEATH. On Easter Monday there were probably not far short of 80,000 visitors to Hampstead Heath. The weather was not all that could have been desired, but remembering what a comparatively few days ago it was since the Heath was covered white with snow, the holiday makers may be congratulated that at the beginning of April they were able to get as much outdoor fun as they did.

The fineness of the early morning led many to start from town soon after breakfast to spend a long day on the people’s favourite and beautiful Heath. Trains, tram-cars and omnibuses brought them up in goodly numbers from all parts and ‘all the fun of the fair’ had commenced when at about half past ten, down came a heavy shower of rain from a sullen-looking sky, threatening to spoil the whole day’s proceedings. Fortunately, however, this proved to be but a passing shower, and thenceforth for several hours fairly fine weather prevailed.

By midday the people were swarming onto the Heath, and for a long time it seemed as if the metropolis was sending all its juvenile population especially in this direction. There was plenty of amusement to be found of the kind in which the Cockney holiday-makers most delight on such occasions. Swings, skipping, pony and donkey riding, peep-shows, and exhibitions of curiosities with numberless coconut shies and try your strength apparatus, were in full operation, as to refreshments, tea and coffee stalls, fried fish establishments, and fruit and ice barrows offered their attractions, and by no means in vain, to the ruralisers around with sharpened appetites.

Conjurers, men on very high stilts, a fire-eater, and Punch and Judy also attracted very large crowds, and numerous pennies, and the swings and steam round-about in the Vale of Health did see a large amount of business.

In spite of some horse-play, especially in the Vale of Health, the holiday makers as a whole, behaved themselves well, and only one or two police charges arose out of the day’s holiday”.

The article mentions the “horse-play” around the Vale of Health and it does seem to have been the location of petty crime – perhaps the large numbers of people attracted to the steam fair was the ideal location for crimes such a pick-pocketing. A report in 1885 regarding the August Bank Holiday mentions the arrest of one William Mitcham, aged 16 from Gunn Street, Spitalfields, who was charged with being a suspected person loitering in the Vale of Health for the purpose of committing a felony by picking pockets.

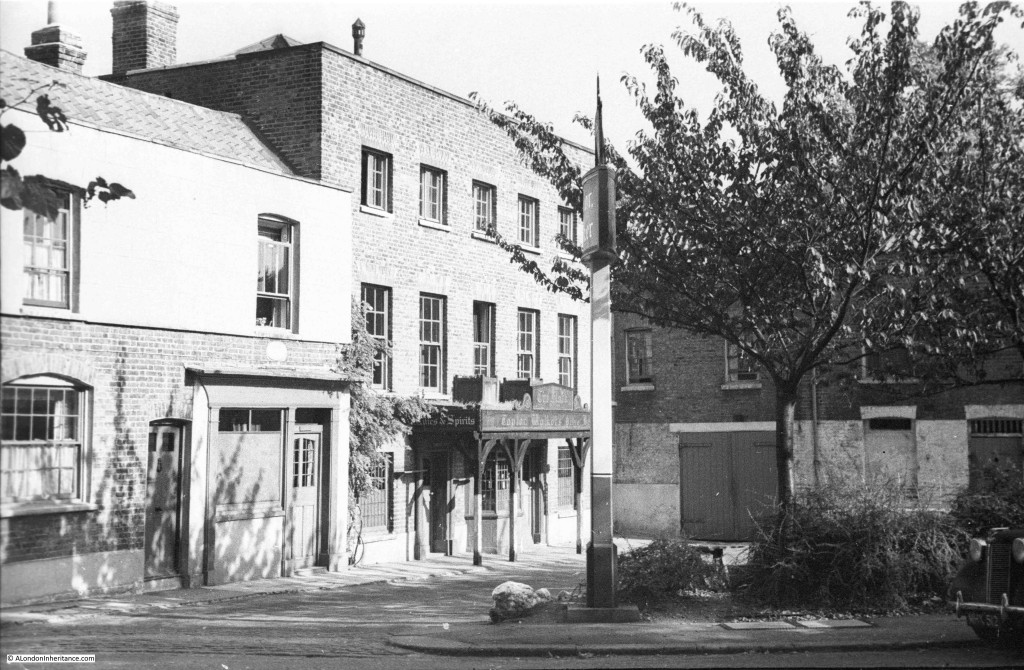

Another of my father’s photos providing a clearer view of the Vale of Health Hotel:

From roughly the same position today, but again showing how much the trees and undergrowth have claimed back the area which presumably was once relatively clear due to the crowds of people that once attended the fair here.

To confirm the name, the following is an extract from the above photo, showing the name on the corner of the signage along the roof line.

The Vale of Health Hotel was demolished around 1962. The Vale of Health was also changing character. No longer the focal point for large numbers of potentially rowdy bank holiday visitors, the area was changing to a rather expensive enclave of housing. A 1962 newspaper article sums up these changes in an article titled “Vale of Wealth”:

“Van horses-what else? There is, of course. Battersea Park, and some people will never forgive Herbert Morrison – Lord Morrison of Lambeth – for setting that up in perennial competition with the old three-times-a-year tradition of the Hampstead Heath Fair.

That fair, in any case, is not what it used to be, what with the etiolated gaieties of the pin-tables. And even the Vale of Health hotel is under threat of being pulled down and made into something rather different.

So Battersea can go on with no serious challenge from the old traditional site. There is, indeed, some rebuilding there and some old Hampsteadians tend to call it now the Vale of Wealth”.

The brick building seen in my 2020 photos on the site of the old Vale of Health Hotel are the flats that were built on the site. They look rather bland from the landward site of the Vale of Health, but walk around the pond and they look very different.

In the following photo, looking across the pond, which was once the Hampstead Water Company reservoir, built after the 1777 draining of the marshy Hatchett’s Bottom, the new flats are within the mainly white coloured building.

The Vale of Health Hotel once faced onto the pond, with verandas around the lower floors providing a lovely location for drinking and eating with a view across the pond.

The following photo from the LMA Collage archive shows the view across the pond to the Vale of Health Hotel, with the fair ground set up to the right of the hotel in the space shown in my photos being used for the storage of fair ground equipment. Comparison of the photos also shows how densely the trees have grown up around the pond.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_143_80_3444

A walk around the pond, and the Vale of Health is a lovely way to spend a Sunday morning. There is a walking route around the unbuilt parts of the pond, starting by the road leading into the Vale of Health.

On the north east side of the pond, this is paved and is one of the many walking routes across the heath, which on a Sunday morning seems to be mainly used by joggers and the occasional dog walker.

Island in the middle of the pond:

View across to the western edge of the pond:

The rear of the flats occupying the site of the Vale of Health hotel. The corner of the block behind the tree is the same corner with the name of the hotel on the top corner of the hotel.

There is a street leading to a dead end that runs in from where the rear of the hotel used to stand. The street also leads to the place where the fair ground equipment was stored in my father’s photo. Although the site of the hotel now has a different use, the area for the fairground is still used for the storage of fairground equipment.

At the top of the street is a brick terrace called Byron Villas, built in 1903. This terrace of houses occupies the spot of another tavern / smaller hotel that once serviced the needs of visitors to the heath. The blue plaque records that the novelist and poet D.H. Lawrence lived in one of the houses in 1915.

The oval plaque on the following building records that newspaper founder and editor Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe lived in the house between 1870 and 1873.

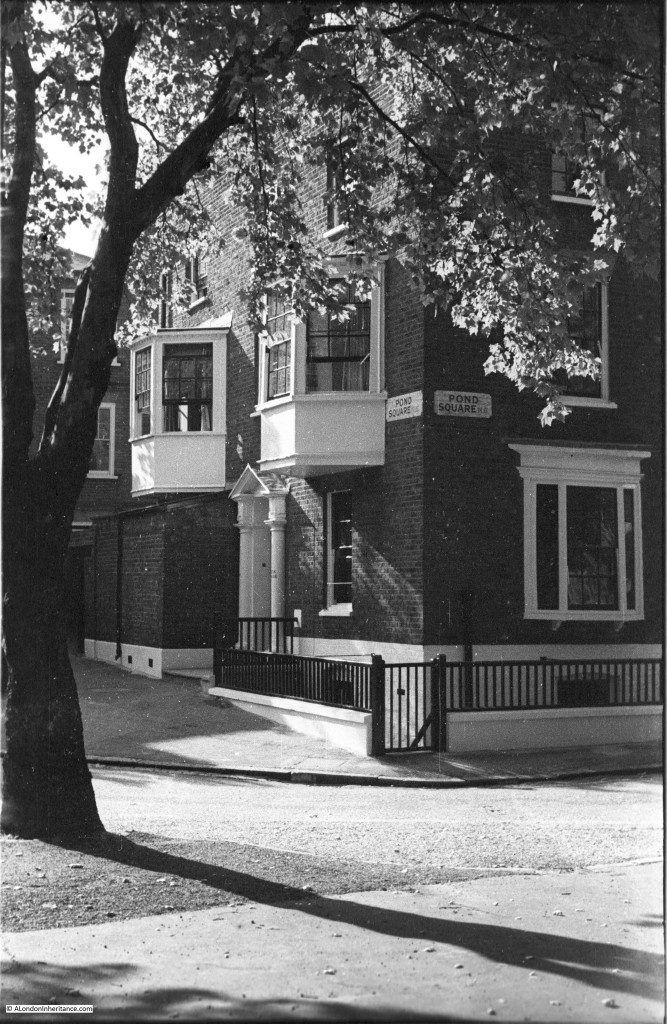

There is a single road in the Vale of Health, conveniently called Vale of Health. Even the spur down to where the old hotel was located has the same name.

Maps show what looks like a road called East View where the fair ground equipment store is located, however in reality, this is a small footpath between the front of the houses and the fairground land.

As well as the single road, there are a couple of alleys alongside the rear of the houses.

House in which Leigh Hunt, the English critic, essayist and poet lived for a time in the Vale of Health.

The Vale of Health is a rather unique area. A small collection of houses embedded in Hampstead Heath, accessed via a single road.

When the new flats were being built on the site of the Vale of Health hotel, there were considerable difficulties with the amount of water that was continuously seeping into the foundations, so perhaps the marshy hollow of Hatchett’s Bottom is still there below the surface,