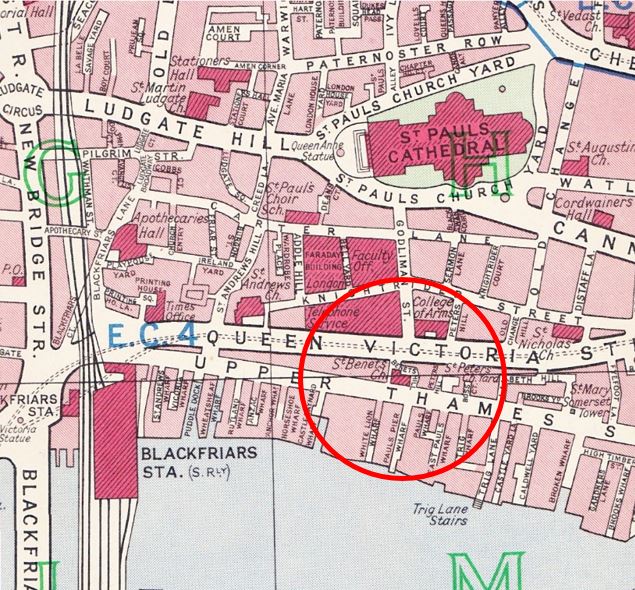

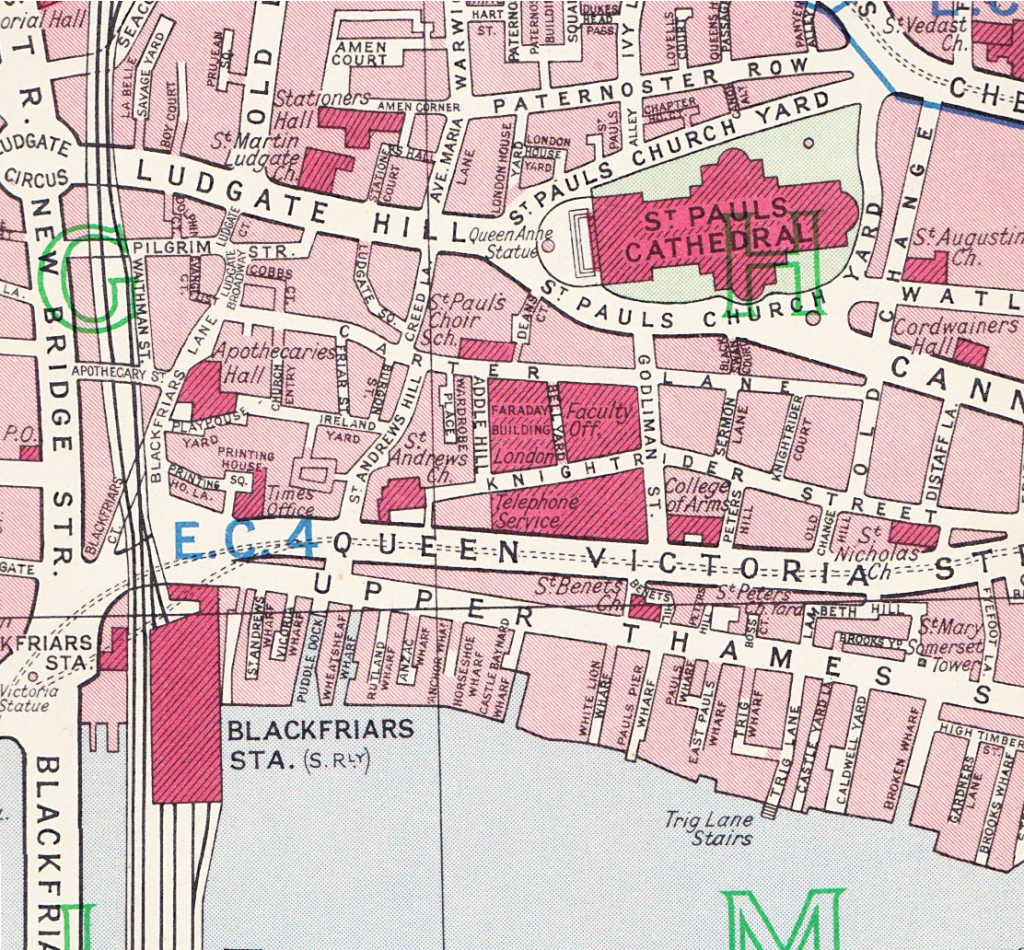

This week’s post is about one small area of London which has changed considerably since the 1940s. The following map is taken from Bartholomew’s Reference Atlas of Great London published in 1940.

Between Upper Thames Street and the River Thames was a network of streets and wharfs leading down to the river. Small inlets such as Puddle Dock, Wheatsheaf Wharf and Castle Baynard Wharf were part of the central London network of docks where goods were unloaded to the warehouses that stood along this stretch of the river.

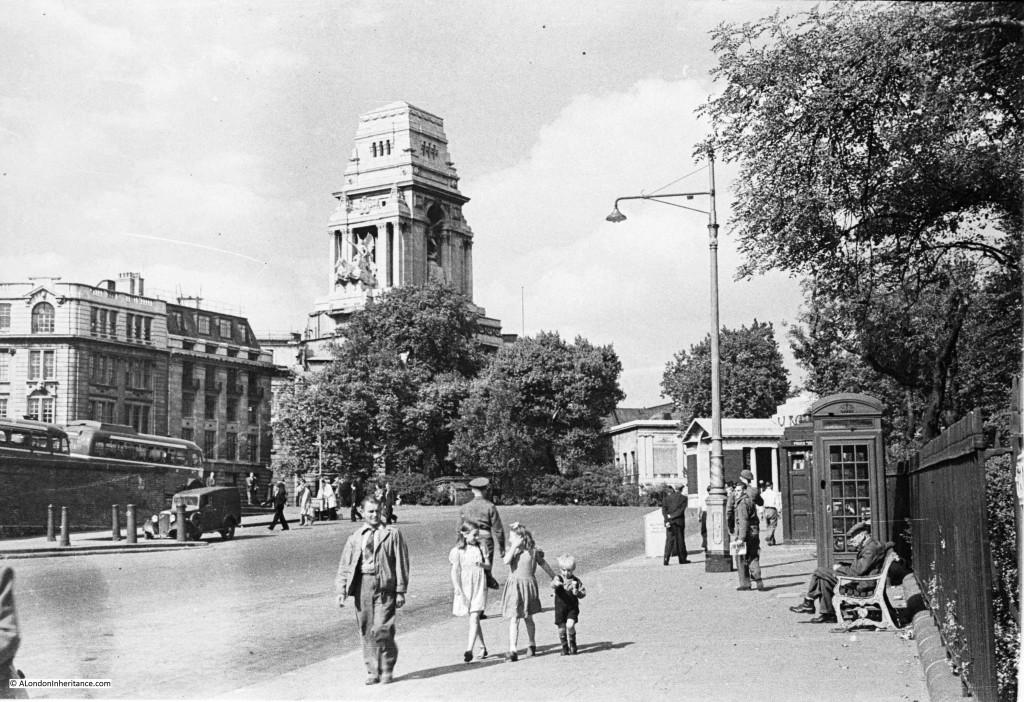

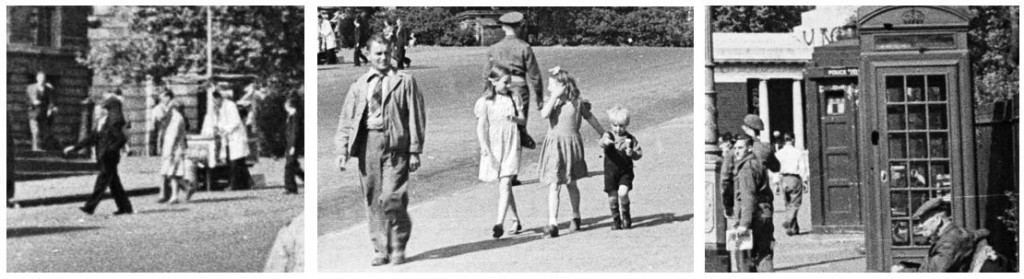

The following photo is one my father took in 1948 and is one that I was having trouble trying to locate despite the very obvious landmark of St. Paul’s Cathedral. The streets are sloping down from St. Paul’s, a clear sign that this photo was taken from the southern side of St. Paul’s, where the land slopes down towards the river. Apart from the cathedral, the only other building with any distinguishing features is the building further up the road with the white brickwork down the corner of the building.

On the building on the left is a small crane located towards the top of the building. A further demonstration of activity in these narrow streets. I imagine that goods being taken to or removed from the warehouse by road would be loaded onto lorries in this side street using the crane to lower from the warehouse. Typical activity that could be found in all the streets and wharfs leading down to the Thames.

Following a walk around Upper Thames Street and Queen Victoria Street, I finally found the location of this photo, however the surrounding area has changed so significantly and the street my father took the photo in does not now exist.

The building with the white brickwork on the corner is the church of St. Benet and the road in which the photo was taken and is running up to the church is Pauls Pier Wharf. I have repeated the map below and circled the area. The church is in the centre of the circle and Pauls Pier Wharf can be seen running down to the river.

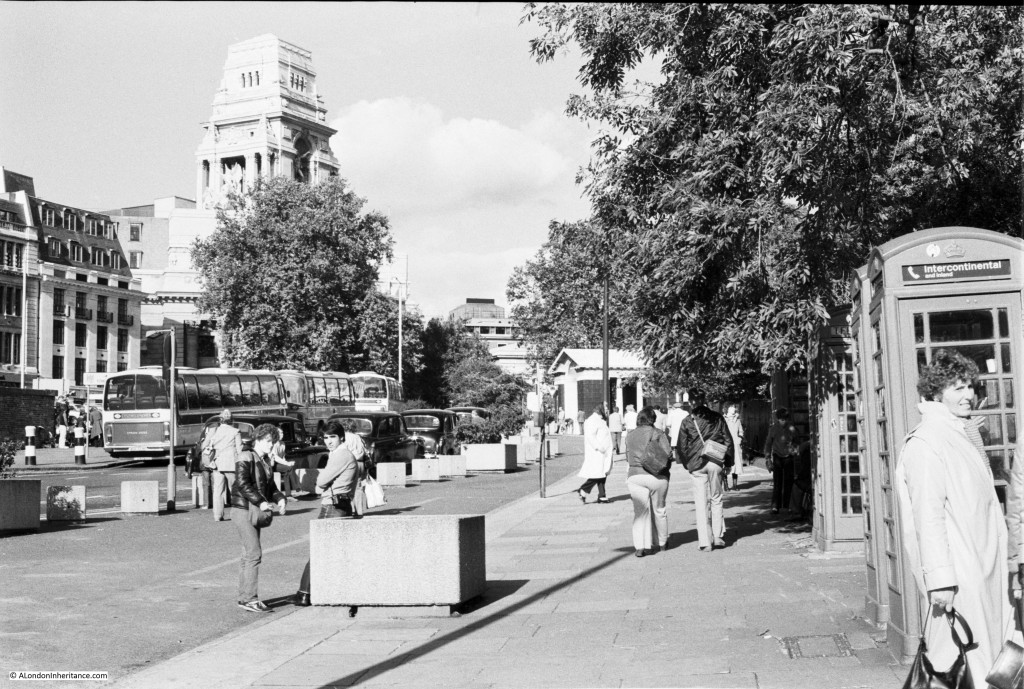

So what is there today? The church remains, but everything else has been lost. When this whole area was redeveloped, Upper Thames Street was widened and rerouted slightly to the south. I could not get to the position where my father took the 1948 photo, however to give some idea of the area now, the following photo is from the elevated Queen Victoria Street. If you go back to the original photo, this is roughly from the same position as from the first floor window of the building at the very top of the street, looking past the church and straight down Pauls Pier Wharf (which is now covered by the building behind the church).

The cobbled road is the remains of Bennets Hill and where it turns right, behind the church, that is the original position of Upper Thames Street. The whole area south of the church, where once Pauls Pier Wharf, Pauls Wharf and East Pauls Wharf used to be is now the 1980’s City of London School which occupies the entire site.

As part of the development of the entire area, Upper Thames Street was moved slightly south and along this stretch it is enclosed within a concrete tunnel with the school being built across the tunnel and down to the frontage on the Thames. The nearest I was able to get to recreate my father’s original photo was up against the wall of the school looking back up Bennet’s Hill. This shows how much of the original street has been lost. To take this photo I was standing roughly where the person crossing the road in the original photo is standing.

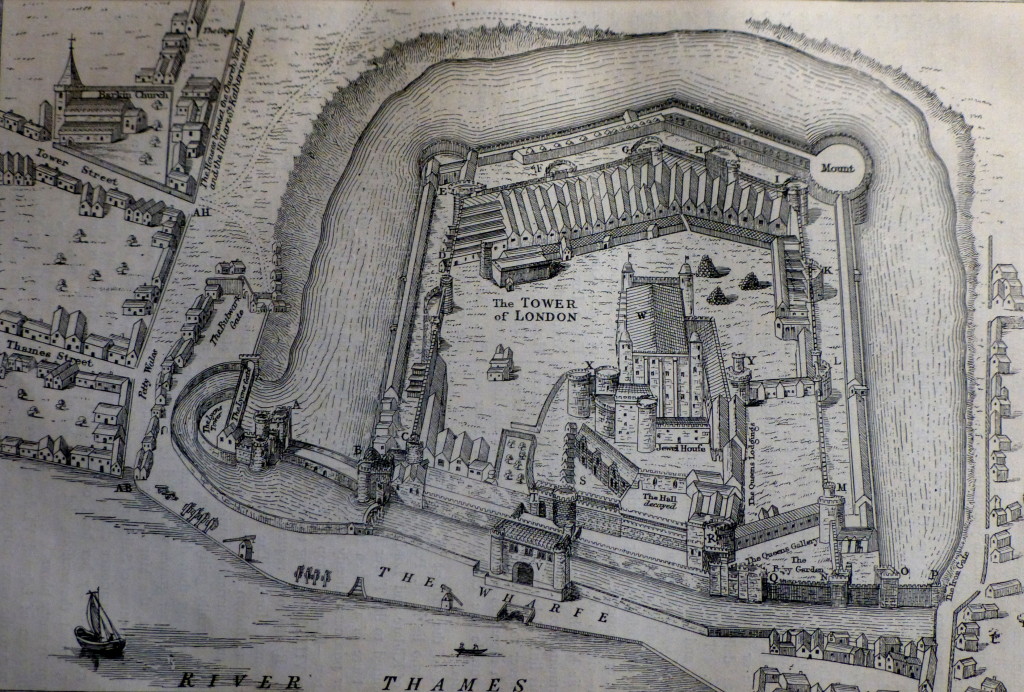

If you walk round to the other side of the church, it is possible to see the original route of White Lion Wharf. Again, this street has been lost and we are looking down into the concrete tunnel that carries Upper Thames Street (the first road in the tunnel is Castle Baynard Street and on the other side of the concrete wall is Upper Thames Street, also in the tunnel). Castle Baynard Street did not exist and is a creation of the redevelopment. It has continued the use of the Castle Baynard name as Castle Baynard Wharf, which was slightly to the west has also been lost. The eastern extremity of Castle Baynard was on this location. More on this in a future post.

On the right is the elevated White Lion Hill which leads from Queen Victoria Street down to the Blackfriars Underpass. Interesting that the White Lion part of the original street name has been retained but is now a Hill rather than a Wharf.

If you walk along the Thames Path a short distance in the direction of Blackfriars Station, and look to your right the road coming down from Queen Victoria Street is what was Puddle Dock as shown in the 1940 map. The road still retains the Puddle Dock name. This is what the old dock looks like now:

A further example of the re-use of the names of the streets and wharfs along this short stretch of the Thames, the Thames path in this section is named Pauls Walk. There were three wharfs with the name Paul; Pauls Pier Wharf, Pauls Wharf and East Pauls Wharf.

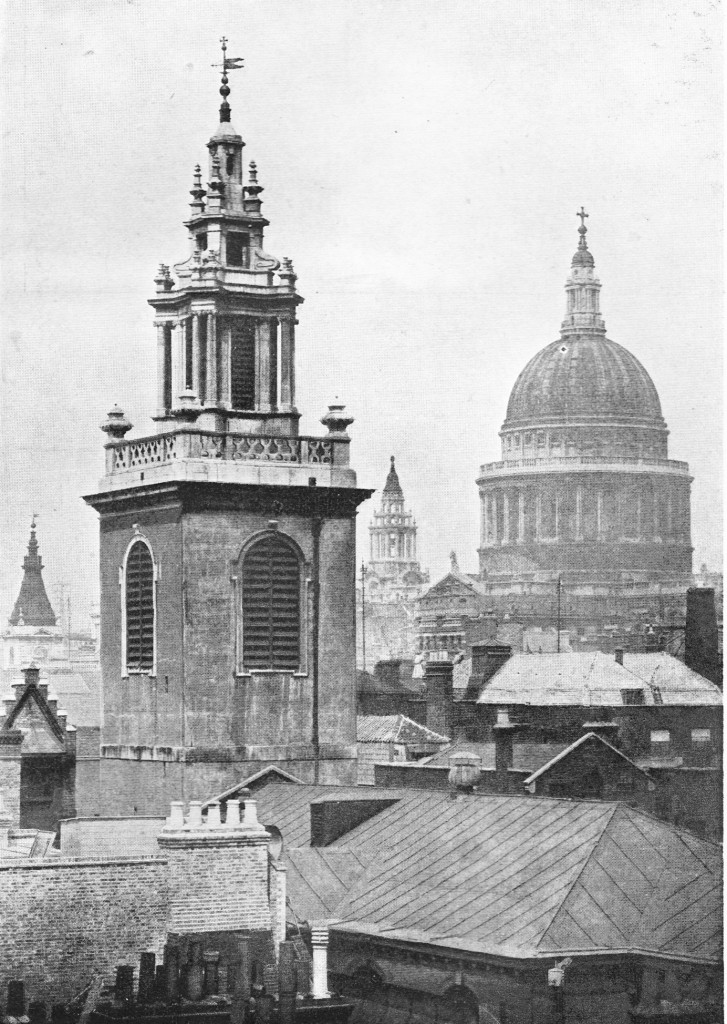

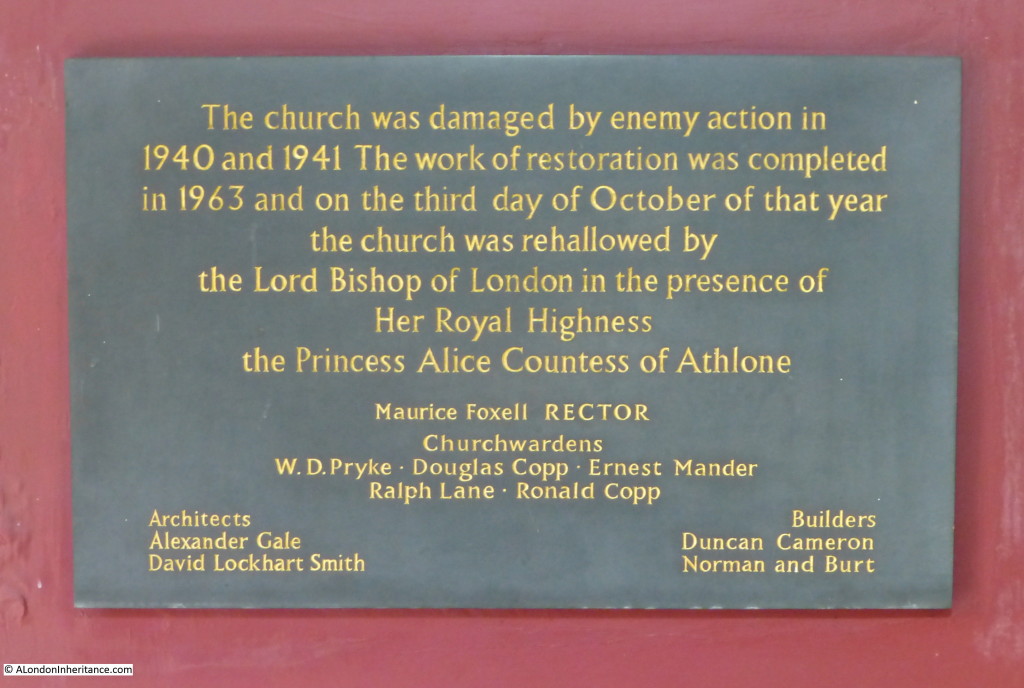

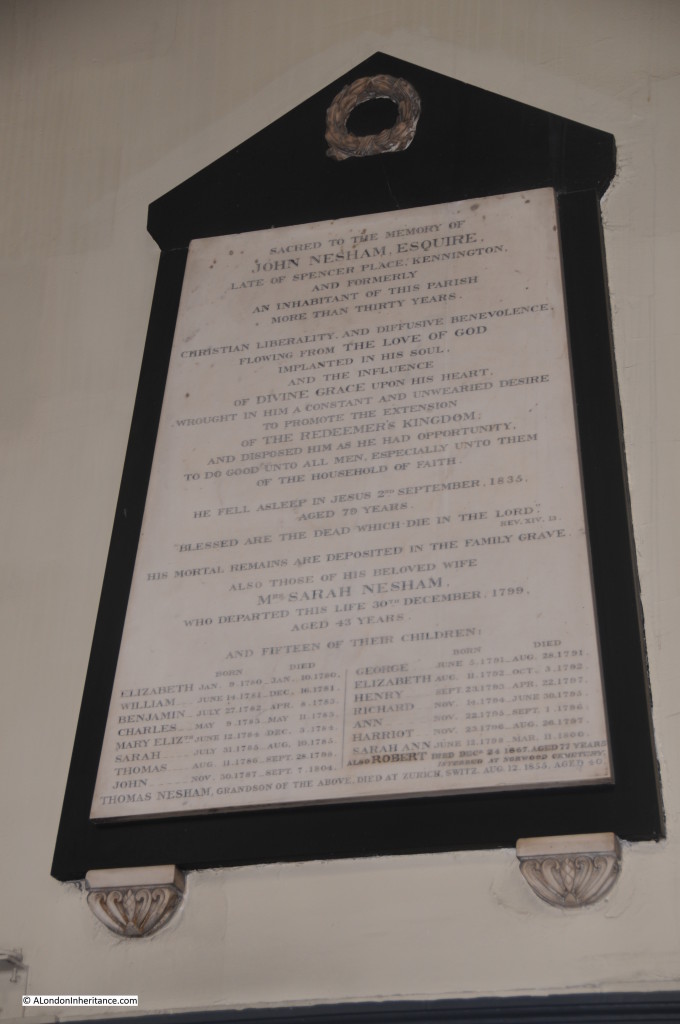

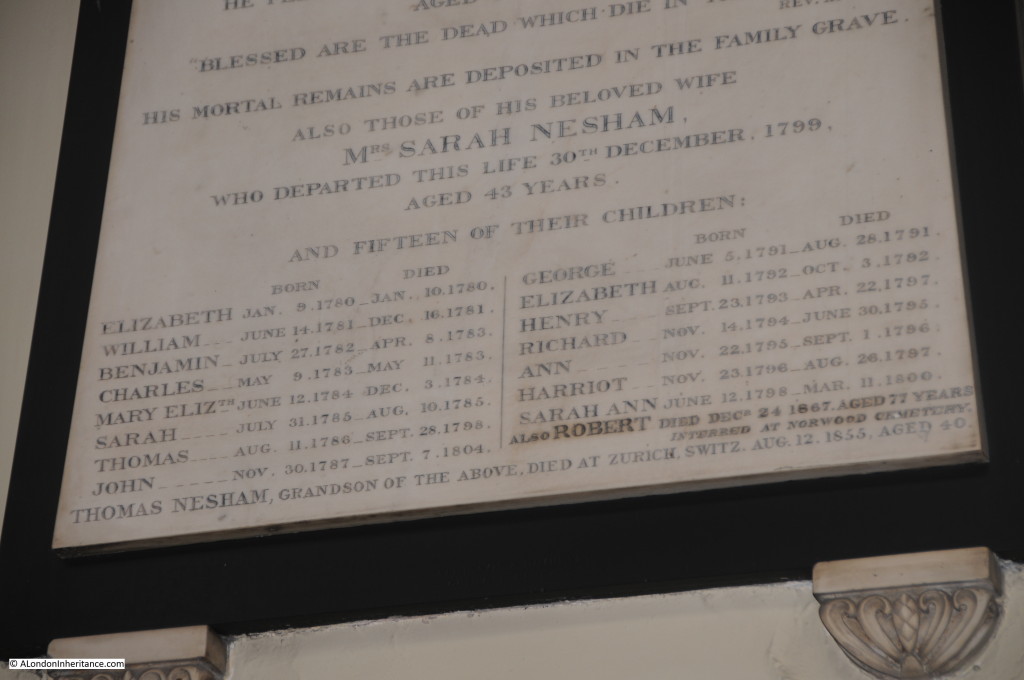

Returning to the church of St. Benet’s, this is an interesting church and well worth a visit. As with many City churches, first records of the church are from the 12th Century. The original church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London and the current church is one of Wren’s rebuilds of the City churches (although probably the design of the church was by Wren’s assistance Robert Hooke). Unlike many of the City churches, it was not damaged in the 2nd World War, indeed unlike so much of Queen Victoria Street and the docks onto the Thames, the small area between St. Benet’s and the river did not receive any significant damage. The church is one of the very few in the City that has not changed that much since construction after the Great Fire.

There was a time though when St. Benet’s was almost lost. In the later half of the 19th century there was a wave of church demolition of those that were perceived to be redundant and St. Benet’s was one of the churches scheduled for demolition, however Welsh Anglicans petitioned Queen Victoria for permission to use the church for services in Welsh. This right was granted and since then services have been conducted in the Welsh language. The Welsh connection is a very strong part of the identity of the church.

An old street sign, now stored inside the church:

The Welsh Dragon as a candle holder:

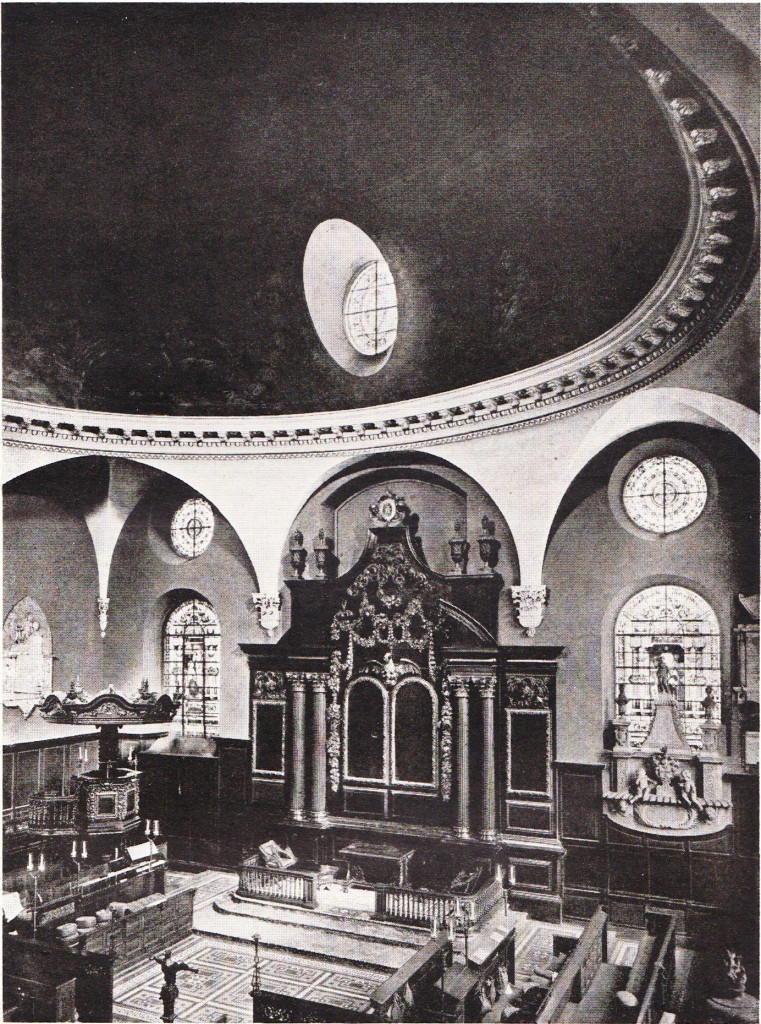

The interior of the church is bright, but with plenty of wood panelling and a large carved, but simple reredos behind the altar.

The 17th century altar / communion table with winged angels supporting a rich cornice and under the table is a figure of Charity with her children:

The view from the gallery:

Back outside the church, and standing on Queen Victoria Street we can look down on the church and Bennet’s Hill. The area north of the church was the original churchyard, however this was lost in the original 19th century widening of Queen Victoria Street.

There is some confusion as to the spelling of Benet in the name of Bennet’s Hill. The church has a single “n” in the name as does the hill in the 1940 street map, however as can be seen below, the modern day street name has “nn”. I have been unable to find whether this spelling change was for a reason or an accident with the new street signs.

Good to see that the original stone carvings above the windows still survive.

Names though do change over the centuries. Stow in 1603 stated that the church was called St. Benet Hude (or hithe) and was up against Powles Wharffe (presumably the same as Pauls Wharf in the 1940 map). Whilst the names change slightly in their spelling it does demonstrate that they have been in existence for many hundreds of years, and for the wharfs and streets they lasted down to the reconstruction of the area in the decades after the war.

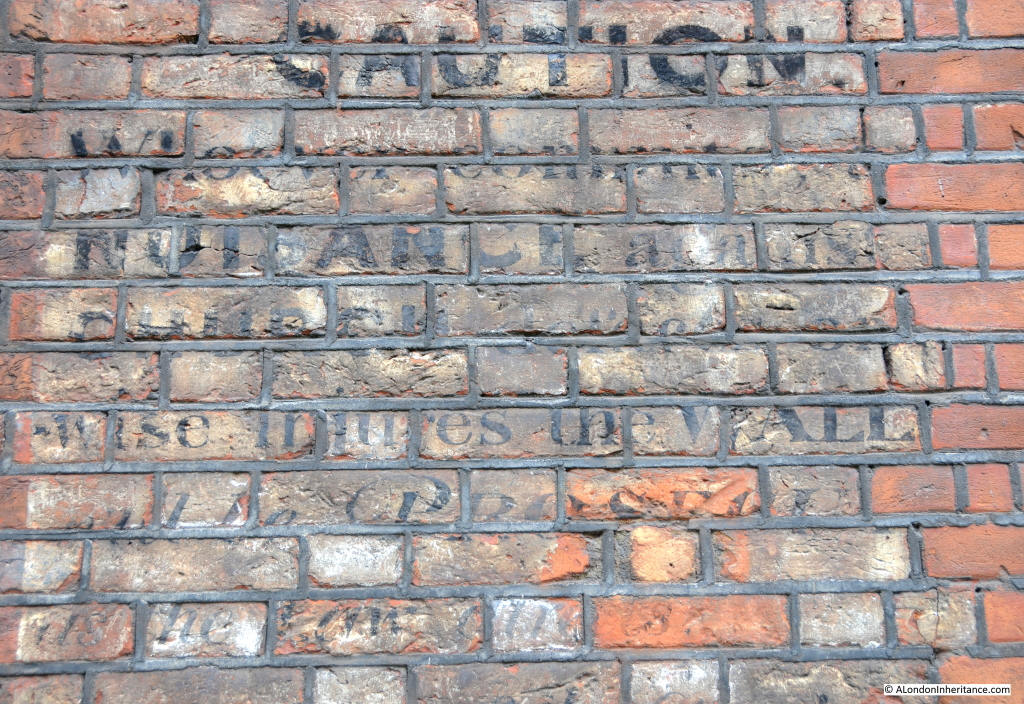

Old ghost sign on the side of the church:

Which seems to read:

CAUTION

Whoever commits NUISANCE against …. church … otherwise injures the WALL will be PROSECUTED ….

One wonders whether the church’s current position, squashed between Queen Victoria Street, the Upper Thames Street tunnels and the elevated White Lion Hill would be considered as committing a nuisance against the church?

The sources I used to research this post are:

- Bartholomew’s Reference Atlas of Greater London published 1940

- The Old Churches Of London by Gerald Cobb published 1942

- London by George H. Cunningham published 1927

- Old & New London by Edward Walford published 1878

- Stow’s Survey of London. Oxford 1908 reprint