My father took a range of photos of the south bank area of London just after the last war, prior to the construction of the Festival of Britain Exhibition.

Some I have already published here and here.

I have been researching and reading about the Festival of Britain and one very good source is the Guide to the South Bank Exhibition that was published to guide the visitor around the site and to provide a “Guide To The Story It Tells”.

The content about the Festival is fascinating, but I also find the adverts within the guide of equal interest. They provide a snapshot of how advertising reflected the country of the time.

The adverts are highly artistic and the colours used are very vivid, probably reflecting the optimism about the future that was one of the main themes of the Festival after so many years of austerity.

The adverts also tell a story of how British industry has changed over the past 64 years.

So, for a change of theme this week, let me show you some of the advertising from the Guide to the South Bank Exhibition.

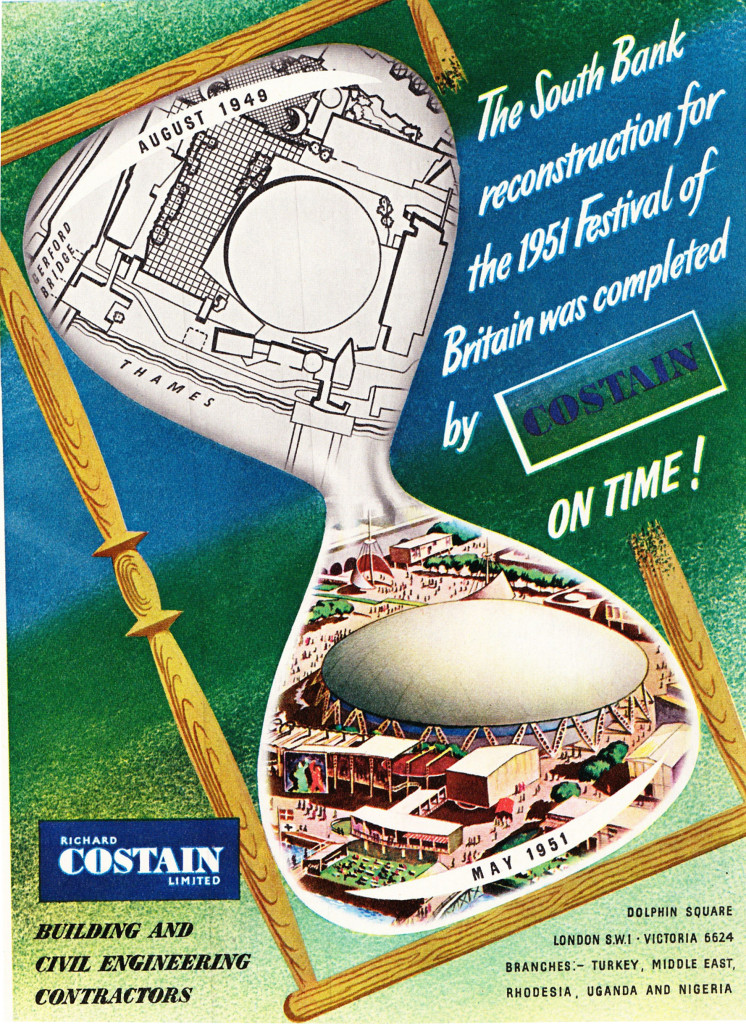

The first is from Costain. A construction company founded in 1865 by Richard Costain who moved from the Isle of Man to Liverpool and began trading as a builder. Costain are still an independent company to this day and are actively involved in many major infrastructure projects around London including the London Bridge station redevelopment.

The advert shows the transformation of the Festival site and the Dome of Discovery from initial plans in 1949 through to completion in May 1951.

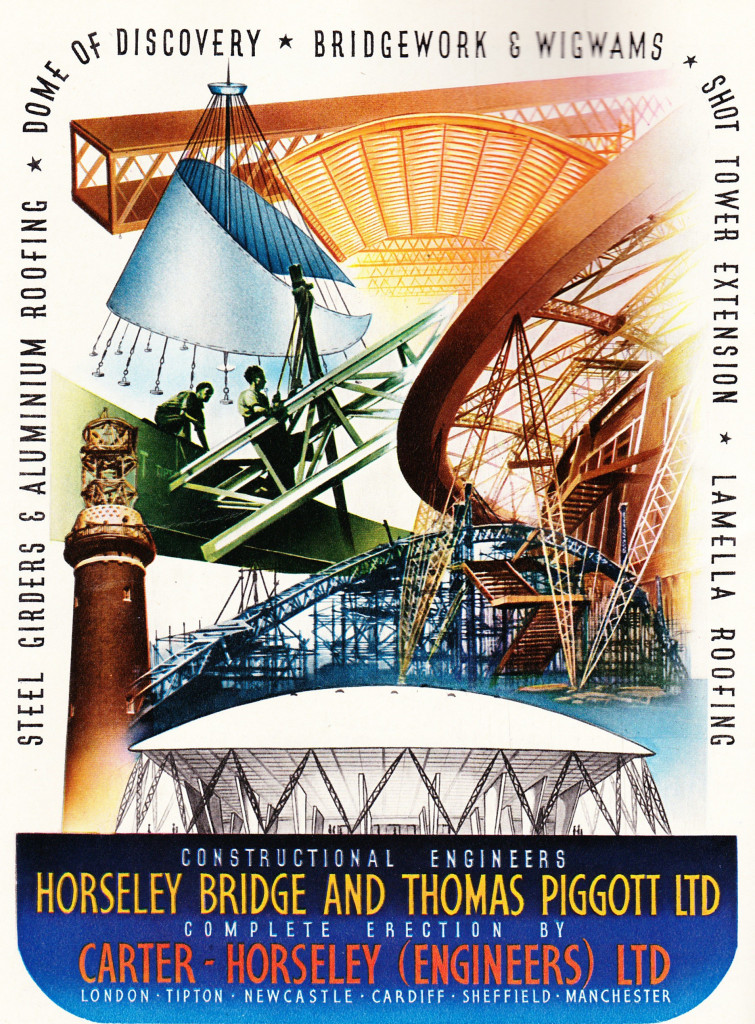

Horseley Bridge and Thomas Piggot were a major firm of construction engineers specialising in iron and steelwork and were responsible for the steel work on the Dome of Discovery. Much of their work remains in use to this day, including Richmond Railway Bridge.

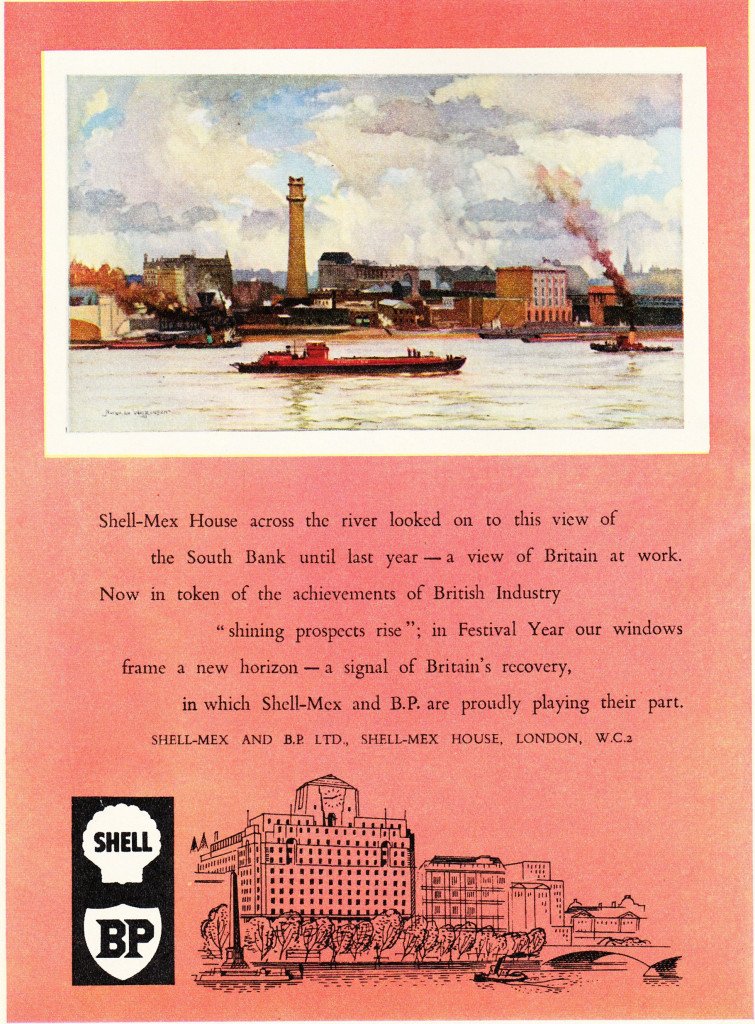

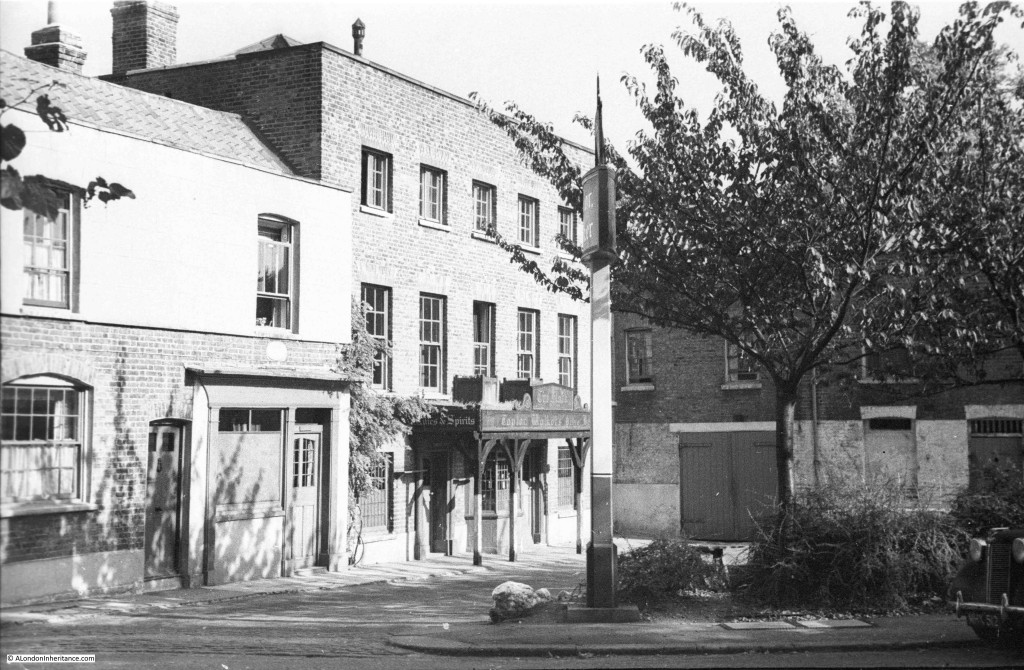

The Shell and BP advert shows the view of part of the Festival site, the current location of the Royal Festival Hall, prior to demolition. The view is from Shell-Mex House which is directly opposite the site on the north bank of the Thames and although not now occupied by Shell, the building is unchanged to this day.

The view of the Festival site shows the Shot Tower on the left and the Lion Brewery building to the right.

Shell would continue to have a link with the Festival of Britain site as following closure, Shell Centre, the head office for the international part of Shell’s business was built on the site.

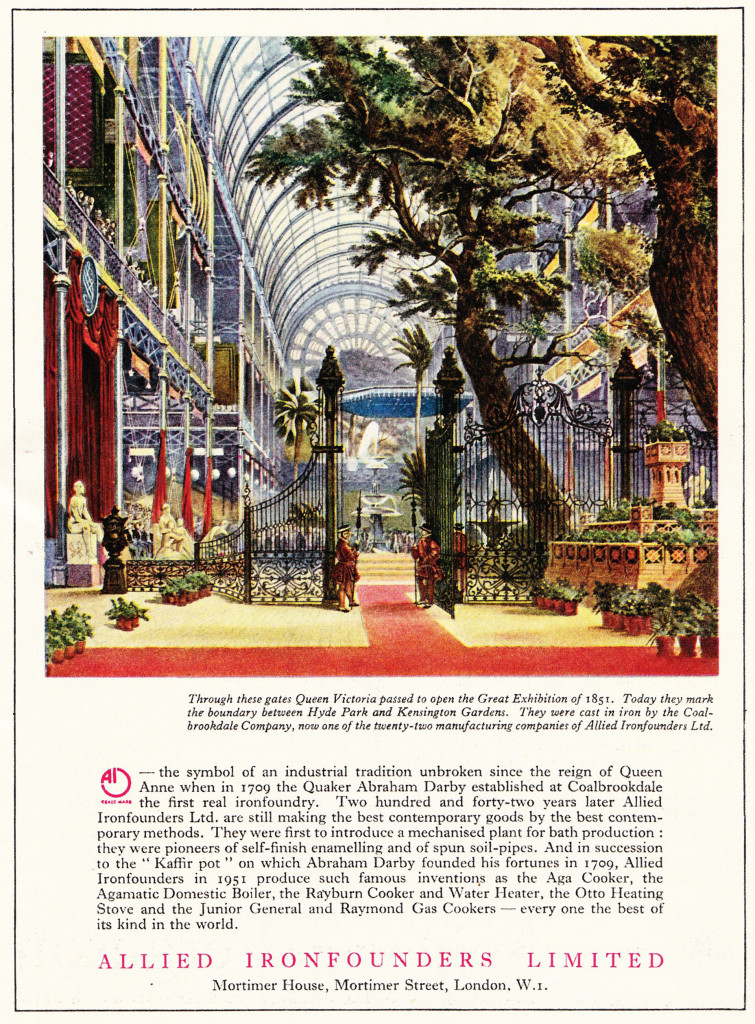

Allied Ironfounders Ltd was formed in 1929 from the consolidation of ten smaller companies and was responsible for a wide range of products including the Aga Cooker through the takeover of Aga Heat in 1935.

Allied Ironfounders lasted as an independent company until 1969 when it was taken over by Glynwed. Within 30 years the company had sold off virtually all of the metal working parts of the business and in 2001 was renamed Aga Foodservice Ltd to concentrate on the remaining part of the business.

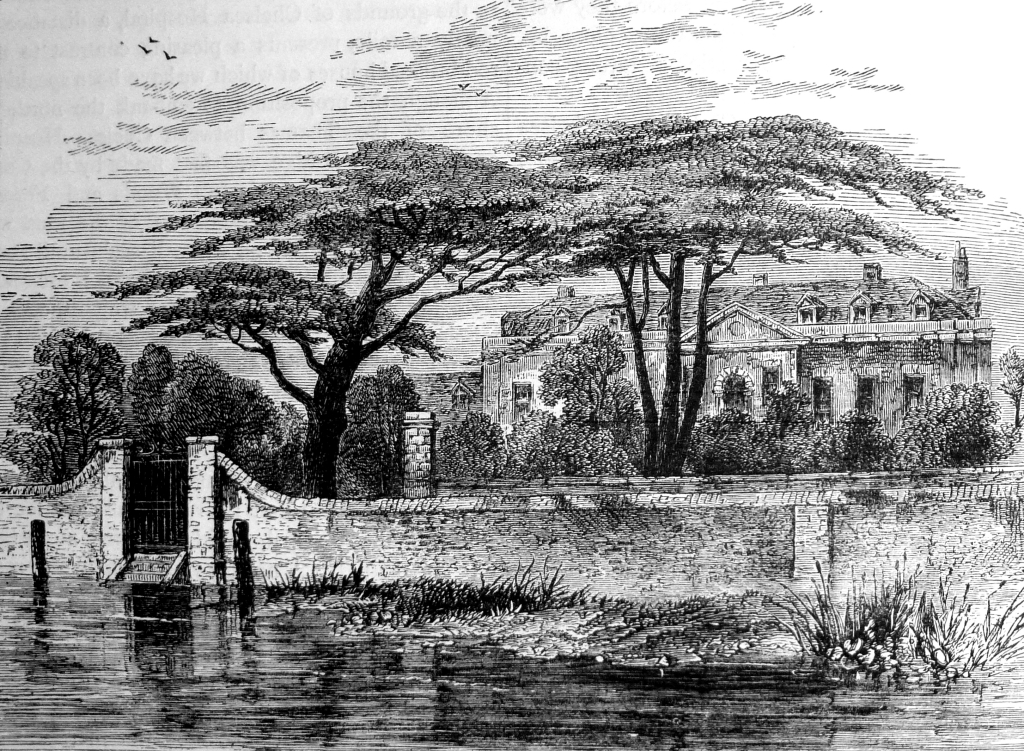

Note the text underneath the illustration regarding the gates from the Great Exhibition of 1851 and their transfer to the boundary between Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens – I did not know that.

Ovaltine was invented by a Swiss chemist in 1904 and was first available in the UK in 1909. Still widely available over one hundred years later and based on the same core ingredient of barley malt. If I have understood chains of ownership correctly, Ovaltine is now owned by Twining’s which in turn is owned by Associated British Foods.

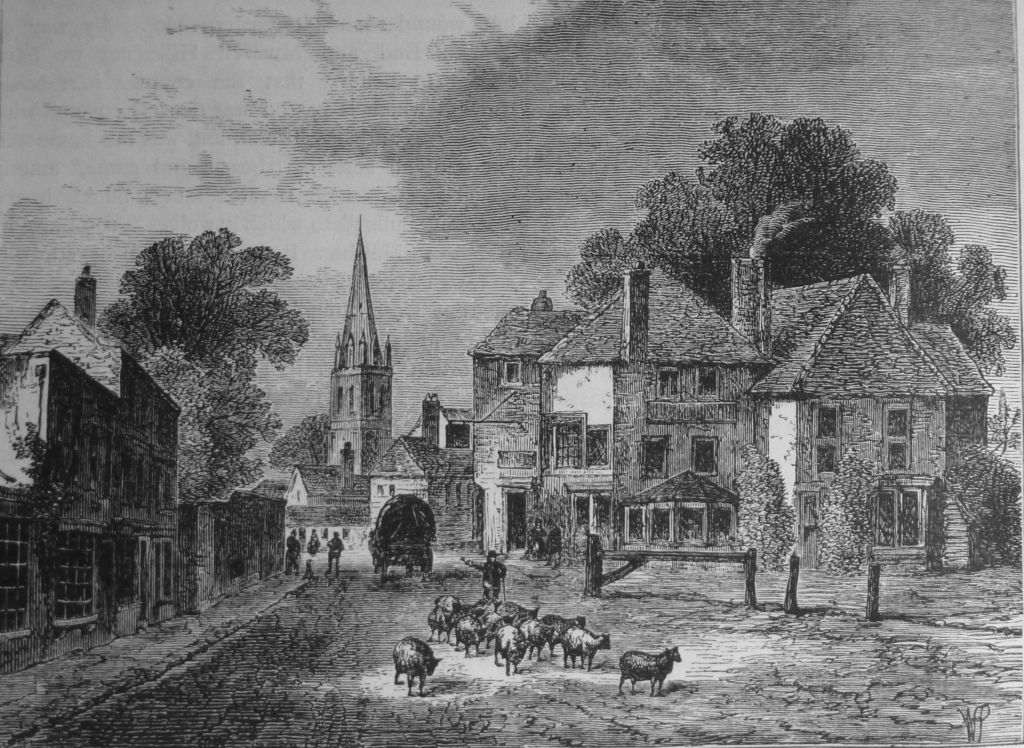

Very idealised view of the Ovaltine Egg Farm, the Ovatine Dairy and the Ovaltine Factory in a Country Garden.

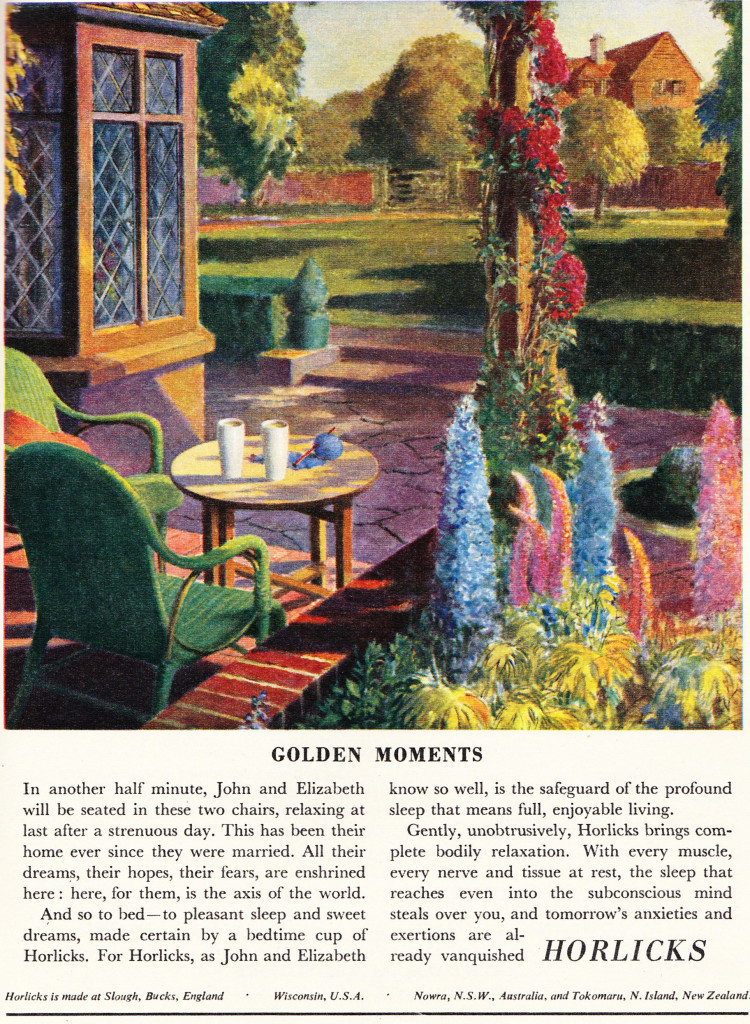

Horlicks is another malted drink which is still in production today, now owned by GlaxoSmithKline (who have their head office in Brentford, West London).

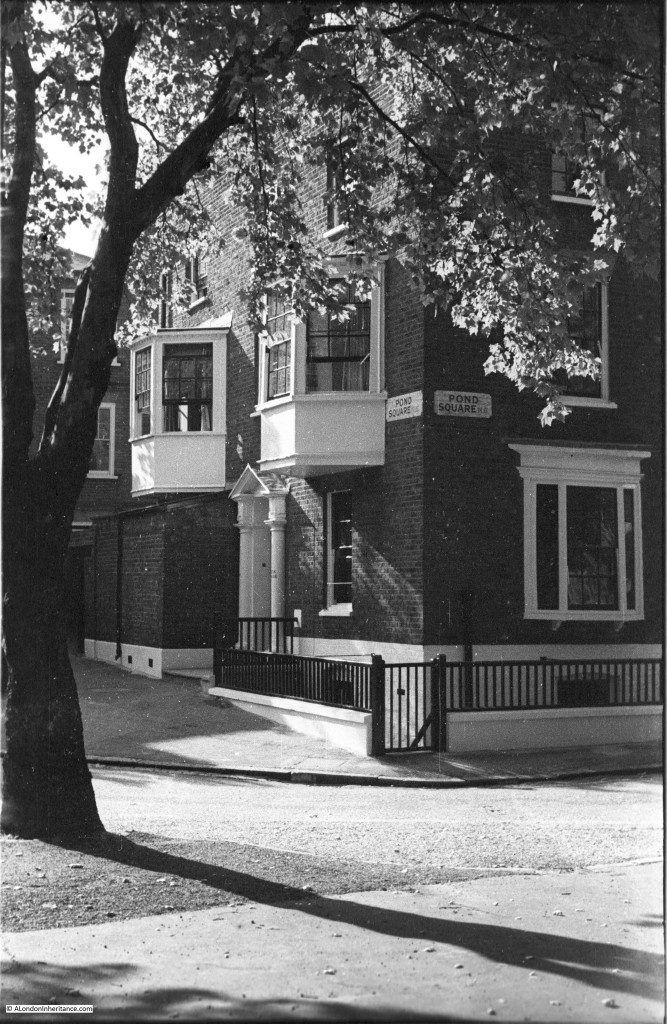

Another idealised view, but this time of a house in the country (very different to the homes of the majority of Londoners at the time)

Barkers of Kensington was a Kensington department store which opened in 1870. Sold to House of Fraser in 1957, it was finally closed in 2006. The Barkers building still remains and is a major landmark on Kensington High Street.

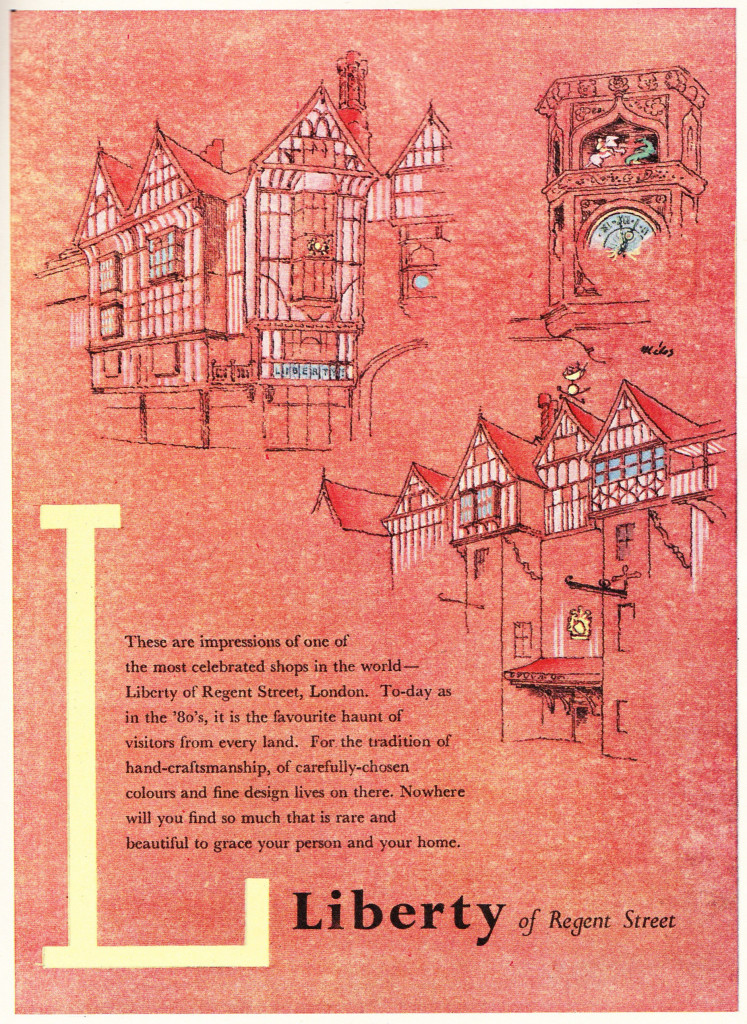

Arthur Lassenby Liberty started trading in Regent Street in 1875. The current store shown in the above advert was built-in 1924. Liberty’s are still trading in the same building to this day with much the same ethos.

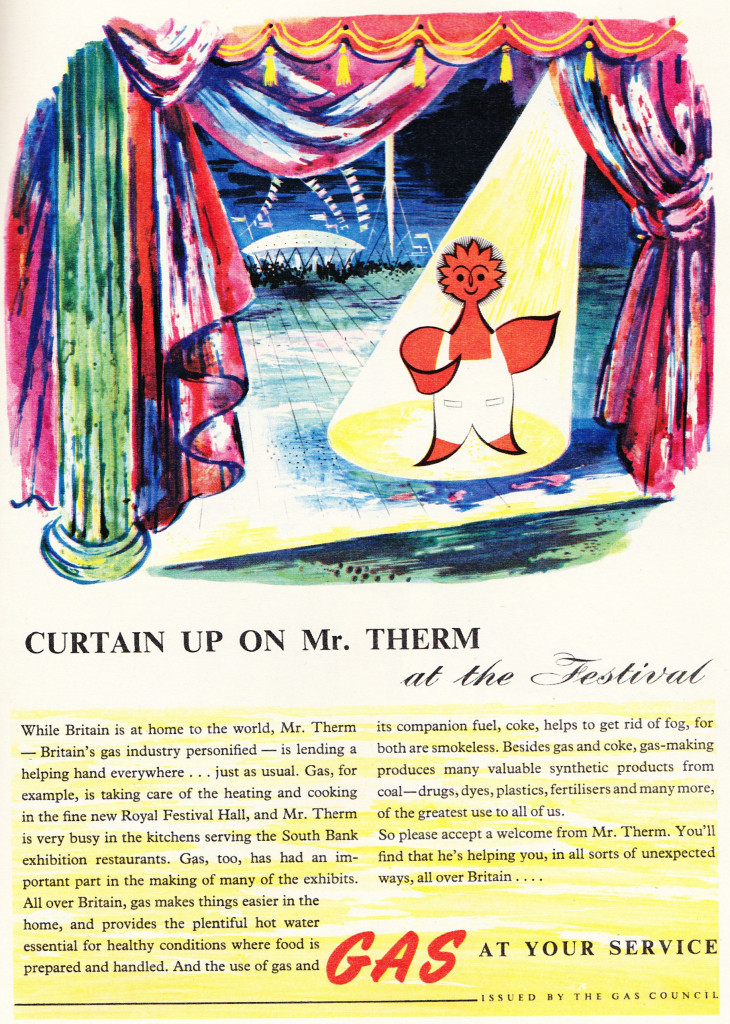

The Gas Council’s advert with Mr Therm standing in front of a backdrop of the festival site with the Dome of Discovery and the Skylon. Gas provision at the time was a nationalised industry, privatised in the 1980s as BG Group and Centrica.

Note the comment about gas and coke helping to get rid of fog – still a major issue in 1950s London.

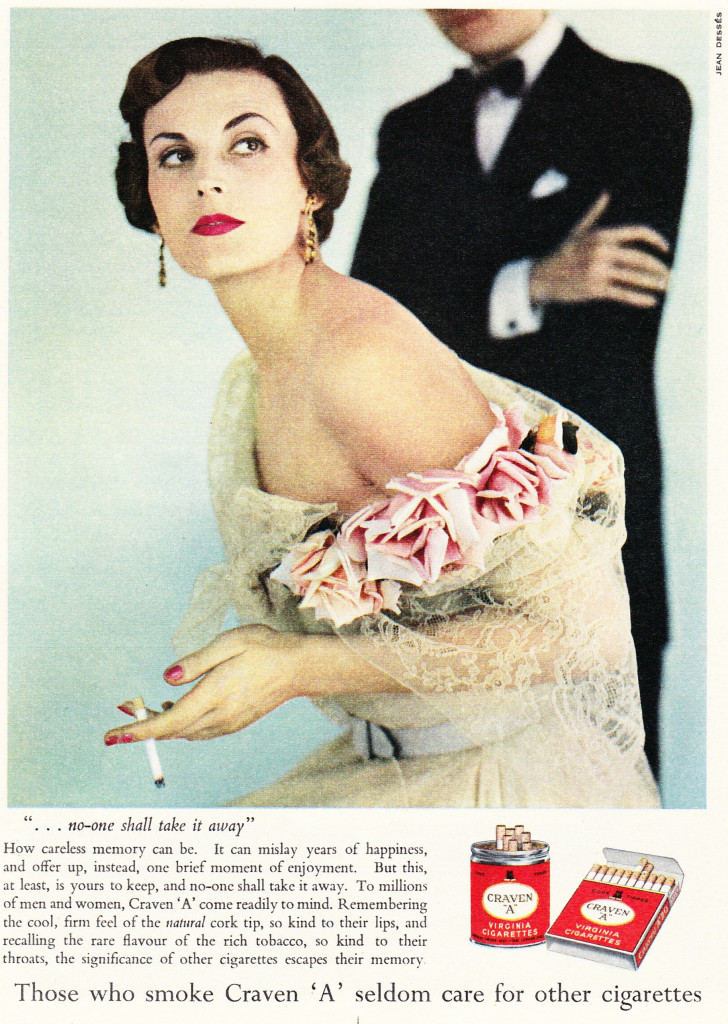

This is an advert you will not see today – cigarettes, in this example Craven ‘A’ trying to project a very sophisticated image for the brand. Still available as a brand today, but as far as I can tell, mainly in Canada.

And perhaps in 1951, to complement your Craven ‘A’ you would also have had a Curtis London Dry Gin, distilled in London since 1769.

Also advertising in the Guide were many of the country’s industrial companies of the early 1950s.

English Electric were a major industrial concern, manufacturing a very wide range of electrical, engineering and aeronautical products and during the early 1960s were a British manufacturer of mainframe computers.

The aeronautical part of the business became a founding member of the British Aircraft Corporation which in turn became BAE Systems.

The rest of the business was merged with GEC in 1968 which spectacularly failed in the first years of the 21st century after the disastrous decision to try to turn the company into an Internet infrastructure business to the detriment of the core engineering parts of the business.

I wonder what those attending the Festival would have thought if they had known that companies that at the time seemed so innovative and core to the country’s industrial identity would have disappeared within 50 years.

Another manufacturer that would disappear was E.K. Cole or Ekco who started manufacturing radio sets from 1924 and later television sets in Leigh-on-Sea and Southend.

Ekco products must have been in many homes across the country at the time of the Festival and must have appeared to be a very strong company and brand.

Ekco merged with Pye, another British electronics manufacturer in 1960 and the combined company was taken over by Philips in 1967 with the Ekco brand disappearing.

Cossor was another British electronics company that would disappear in a couple of decades. The company started trading in 1859 as a manufacturer of scientific glassware and this expertise helped the company move into the production of electronic valves and cathode ray tubes. This led into leading technologies such as radar both during the 2nd World War where Cossor was one the companies that helped develop the Chain Home radar system along the coast and following the war into radar for air traffic control.

Cossor was purchased by the US manufacturer Raytheon in 1961, just ten years after the Festival of Britain and is another example of the loss of British industrial capability over the last 60 years.

Sperry was a manufacturer of navigation equipment and gyrocompasses. Now owned by the American business Northrop Grumman Corporation.

Siemens Brothers and Company Limited was the 1951 incarnation of the original Siemens company formed in 1843 by Wilhelm Siemens of Germany. The shares of the British business were confiscated at the start of the 1st World War and finally became part of Associated Electrical Industries in 1955 which then merged with GEC in 1967 which as stated above with English Electric failed in the early 2000s.

The original German part of Siemens is now a major global manufacturer and well established in the UK, manufacturing in Germany many of the trains that now service London

One brand that is still very much in business today is Cow and Gate. originally a grocery shop in Guildford owned by the Gates family in 1771, the business expanded into dairy products which led to powered milk and then to milk food for babies.

Smiler, the Cow and Gate “royal baby” was introduced to the branding in 1930.

Although still in business, Cow and Gate is now owned by the French multinational Groupe Danone.

The Festival of Britain and the South Bank Exhibition that formed the core of the Festival was intended to show a strong, confident country, full of innovative industrial and manufacturing companies that could be expected to bring a prosperous future after the long years of war and the austerity that followed. The following decades would bring significant change to, and the demise of many of these companies.

I have shown just under half of the adverts featured in the 1951 Guide to the Festival, the rest have the same standards of artwork and it is interesting that there is only one financial business (Lloyds Bank) featured. Again perhaps how the country (or at least the organisers of the festival) wanted to portray what was important to the country and to the future from the perspective of 1951.