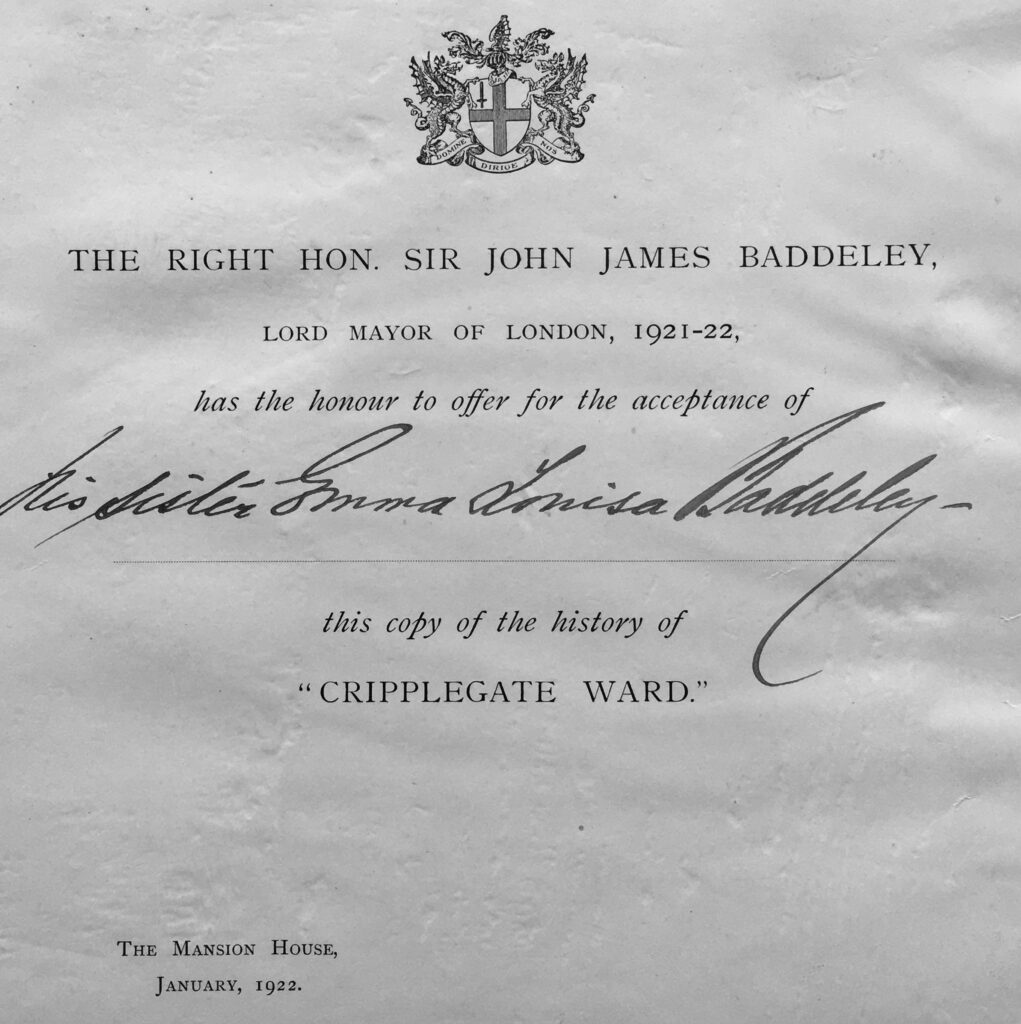

I am fascinated by the journey that books take over the years. I have a copy of a book titled “Cripplegate Ward” by Sir John James Baddeley, published in 1921.

Baddeley was the Lord Mayor of London between 1921 and 1922, and on the inside cover of the book is pasted a square of paper detailing Baddeley’s presentation of this copy of the book to his sister Emma Louisa Baddeley:

As it is roughly 100 years since Baddeley gave the book to his sister, I thought it would be a good time to revisit Cripplegate Ward, using the book as a guide.

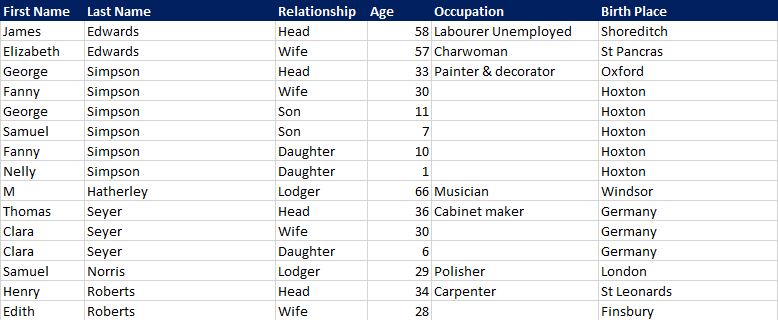

Baddeley describes Cripplegate as the second largest ward in the City (Farringdon Without being the larger), covering an area of 63 acres, nearly a tenth of the whole City. In the last census (1911) before Badderley’s book was printed, the ward had a population of 36,793, the majority of whom were employed in the various warehouses and factories that could be found across the ward.

Cripplegate was / is divided into Cripplegate Within and Without to describe those parts of the ward that were in the City side of the old Roman wall, and the area on the outside of the wall. That demarcation makes very little difference today, but would have been important when the wall was still a feature of the landscape.

Whilst I have written about Cripplegate in a number of previous posts, what I also find fascinating is gradually peeling back the layers of the history of a place, and finding more detail than I have already covered, so for today’s post I want to explore two places within Cripplegate ward that I have not written about before. The first is:

Lady Eleanor Holles School

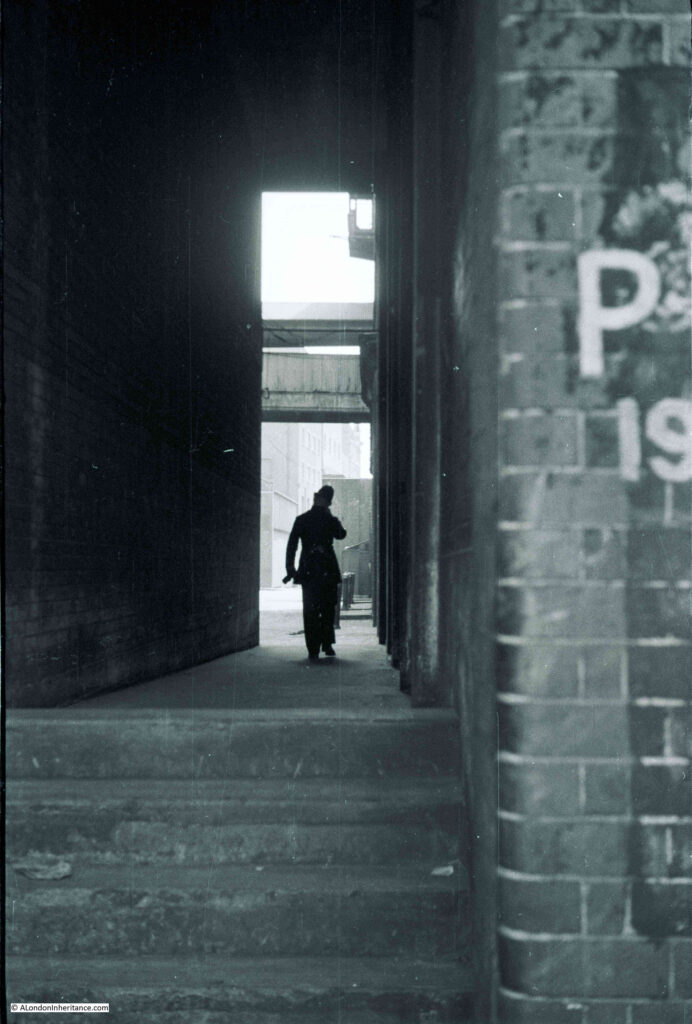

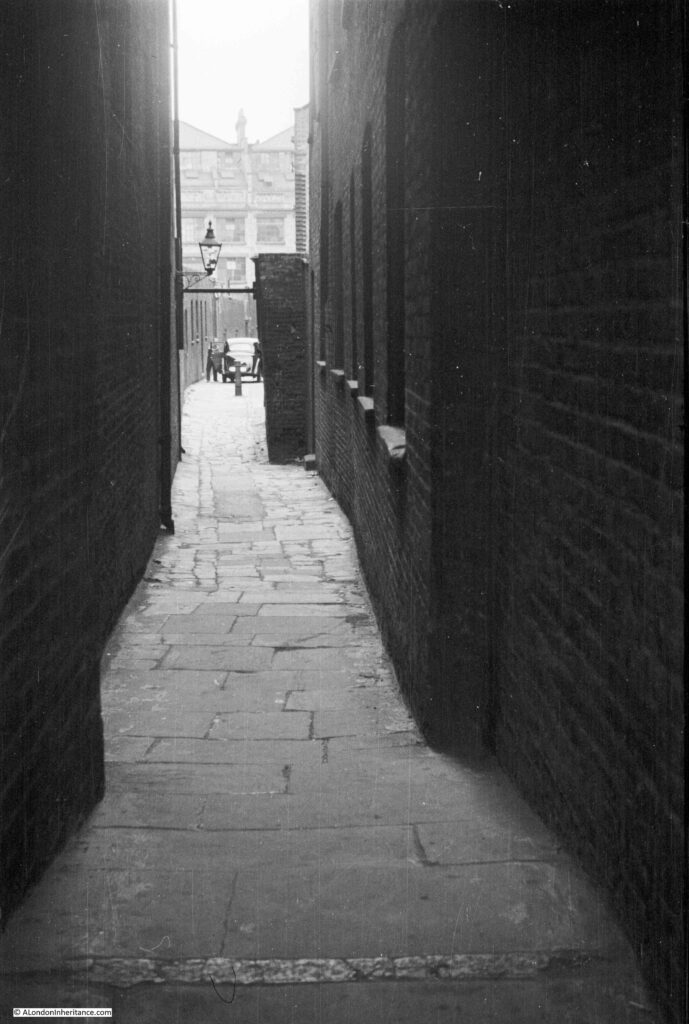

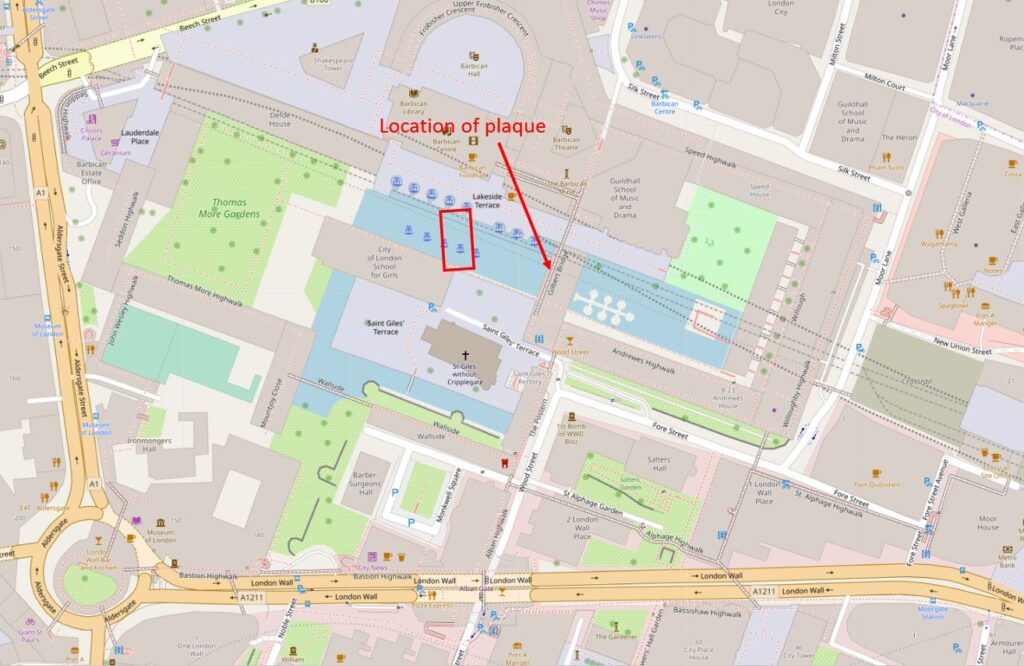

There is an elevated walkway underneath Gilbert House within the Barbican estate. The walkway is lined by a number of round, concrete pillars that support the building above, and on one of these pillars is the following plaque:

The plaque records the foundation in 1711 of the Lady Eleanor Holles School near the site of the plaque. The plaque is on the pillar arrowed in the following photo, which shows the location and view out to the central area of water in the Barbican:

Cripplegate Ward by Baddeley, along with an article on the history of the school in the City Press on the 24th of July 1869 both provide some background into the Lady Eleanor Holles School.

Lady Eleanor Holles died in 1708, and in her will asked that her executor, a Mrs Anne Watson, dispose of her estate “to such pious purposes as her executor might think best”. Her estate consisted of land and a number of properties which produced an income of £62 and 3 shillings a year.

There was already a boys school in Redcross Street, Cripplegate, and Mrs Anne Watson arranged that the properties from Eleanor Holles will were committed to a body of trustees, and the funds used for the creation of a girls school, consisting of “a schoolmistress and the education of fifty poor girls”, and to be known as “the Lady Holles’ Charity School”.

There is no record as to why Anne Watson chose the poor of Cripplegate to be the beneficiary of the Eleanor Hollis will, however Anne Watson appears to have been deeply interested in promoting education for the poor as in her own will she left £500 for a charity school.

Around the start of the 18th century, there were concerns regarding the lack of education for children of the poor, and what this meant for the promotion of “Christian principles”.

According to the City Press, the school “undoubtedly owes its origin to that general movement in favour of the religious education of the poor in the principles of Protestantism which took place in the latter stages of the seventeenth century”. Baddeley also adds that a document in possession of the treasurer of the school and written in 1709 states that “It is evident to common observation that the growth of vice and debauchery is greatly owing to the gross ignorance of the principles of the Christian religion, and Christian virtues can grow from no other root than Christian principles”.

The original school used rooms leased from the boys school, which was located towards the northern end of Redcross Street. In 1831 the enlargement of the school was proposed, and a new school for the girls was built at the southern end of Redcross Street.

I have circled the location of this school (marked as School Girls) on the 1894 Ordnance Survey map below (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

The school was located where Fore Street turned into Redcross Street. I have marked the location on a map of the area today (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

The plaque photographed earlier in the post is on the walkway under Gilbert House (arrowed in the map above), and the red rectangle shows the location of the school which would have been facing onto Redcross Street, which ran from just above the left of the church, past the school and into what are now the buildings of the Barbican.

The school went through a number of enlargements during the 19th century, and the final build of the early 1860s created a school with a capacity for 300 girls and 100 infants, residence for the school mistresses and a board room for the governors.

In the mid 19th century, the school seems to have been doing financially rather well, as in an 1868 survey of the “Thirty Three City of London Endowed Schools for Primary Instruction for Boys and Girls”, Lady Eleanor Holles school was identified as having the largest endowment, with an annual income of £1,377.

As with many charity schools throughout London, the Lady Eleanor Holles School had the sculptured figure of one of the scholars mounted on the front of the building. The following image of the figure, showing the collar, cap and clothes that would have been worn by the girls comes from Baddeley’s book on Cripplegate Ward:

The girls were instructed in the practice of the Christian religion. They were taught to spell, read and sew.

Although the school could support a large number of girls and infants, towards the end of the 19th century the majority of pupils were coming from outside the parish of St Giles, Cripplegate. This was down to the reduction in the number of dwelling houses in the area as more factories and warehouses were constructed.

The school was also in competition with the new schools created by the London Schools Board, which were being funded through the rates and parliamentary grants, rather than through charity donations and fees.

The future of the school was decided by the London County County who were looking for a site to construct a large, new fire station.

The LCC offered the trustees of the Lady Eleanor Holles School a sum of £30,000 for the land and buildings. The school trustees accepted, and moved to a new location in Mare Street, Hackney.

The reason for a new fire station in Redcross Street can be seen in this article from Lloyds Weekly Newspaper on the 4th of December 1898:

“Hitherto Watling-street has been the chief City fire station, and the proposed change would be of great advantage, as the warehouses in the vicinity of Wood-street are filled, as a rule, with the most combustible materials. On the northern side the station would be of very great utility to the over-crowded districts of St. Luke’s and Shoreditch, where most houses are old and the danger of fire considerable.”

I have written about the Redcross Street fire station in a previous post, as it was a central feature in one of my father’s post war photos of the area now occupied by the Barbican and Golden Lane estates. The post can be found here, and covers the story of the fire station during the blitz, Redcross Street, and the surrounding area.

What I did not have time to cover in the earlier post was the history of the school, so in the following photo, St Giles is the church which is still a central feature in the Barbican. Redcross Street fire station is the large building on the left, and the rest of the area shows the devastation of bombing, mainly on the night of the 29th December, 1940.

So, part of the area now occupied by the central water feature in the Barbican was once the site of the Redcross Street fire station, and before that, was the site of the Lady Eleanor Holles School for Girls.

The school, and fire station were once located in the centre of the lake in the following photo, just behind the tall grasses on the left. The walkway with the pillar and the plaque is in the background, underneath Gilbert House:

The above photo also shows how Gilbert House is supported by a relatively few number of slender pillars.

The Lady Eleanor Holles school remained at Mare Street, Hackney until the mid 1930s, when for similar reasons to the challenges of the late 19th century (industrialisation of the area, competition with many other local schools), the school decided to relocate out of central London and moved to a temporary location in Teddington, whilst a new school building was constructed at Hanworth Road, Hampton.

The Lady Eleanor Holles school continues to be based in Hampton and is rated as one of the leading independent girls schools in the country.

A very different location, but maintains the name of Lady Eleanor Holles, who left sufficient money through her property, to establish the original girls school in Redcross Street in 1711.

My second location for this week’s post on Cripplegate Ward is the feature that would give the ward its name:

Cripplegate

Wood Street runs from Gresham Street, across London Wall, finishing with a short stretch where it turns into Fore Street. Just before the junction with Fore Street, Roman House can be found on the right, and on the side of this building is the following plaque:

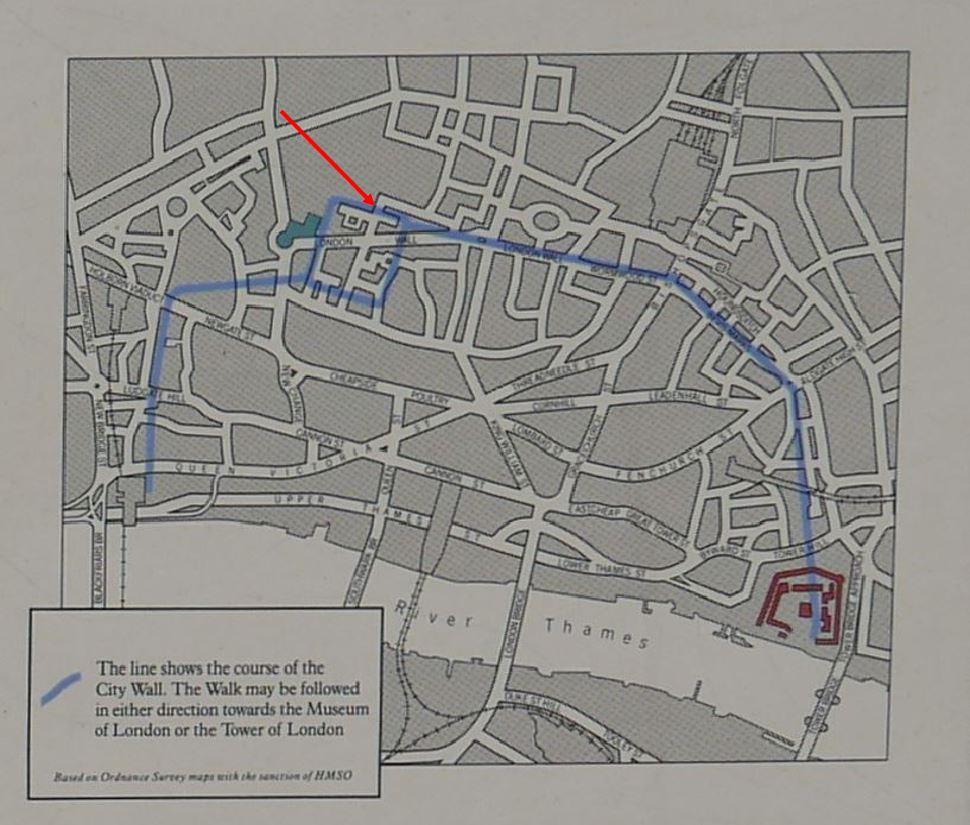

Cripplegate was the original northern gate to the Roman fort which occupied the north west corner of the old Roman City. The fort was discovered during post war excavations by Professor W.F. Grimes, and the location and size of the fort is shown by the blue rectangle in the following map of the wall from one of the plaques showing the route of the wall. The location of the gate is shown by the red arrow.

The plaque is on the right of the following photo of the northern section of Wood Street, the gate would have been across the street, to the left of the plaque.

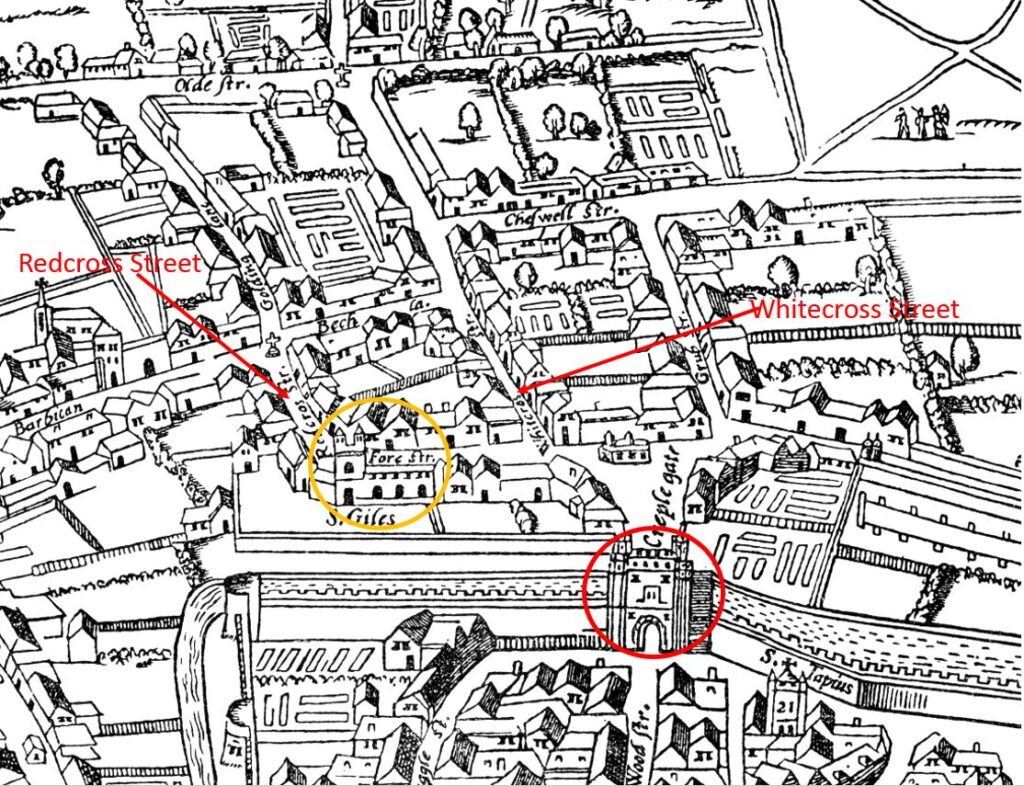

The gate is shown in the modified 1633 version of the early Agas map of London, the red circle in the following map surrounds the gate. The orange circle surrounds St Giles, Cripplegate, and Redcross Street, the site of the school and fire station is on the left and Whitecross Street on the right:

The name of the gate has long been the subject of speculation. A news article from 1904 reads:

“The origin of the name of Cripplegate, in which stands the church of St Giles, has long puzzled the minds of antiquaries. Ben Johnson averred that the street took its name from a crippled philanthropist, but Stow says the name was derived from the thronging of cripples which frequented it for begging purposes. It seems however, now to be decided that the name comes from ‘Crepel-gate’ a covered way in the fortifications. There is still a strong belief prevailing, however, that when the body of St. Edmund was brought from Bury to save it from the Danes, crippled persons by the wayside were cured of their afflictions as the body passed, and that the church of St Giles, the patron saint of cripples, was erected in commemoration of the miracle.”

Baddeley, in his book on Cripplegate Ward provides more:

“The etymology must be sought elsewhere. Cripple-gate was a postern gate leading to the Barbican, while this watch-tower in advance of the City walls was fortified. The road between the postern and the burghkenning (Barbican) ran necessarily between two low walls – most likely of earth – which formed what in fortification would be described as a covered way. The name in Anglo-Saxon would be ‘Crepel’, ‘Cryfele’ or ‘Crypele’, a den or passage under ground, a barrow, and geat, a gate, street or way.”

The book “The Ward of Cripplegate in the City of London”, (1985) by Caroline Gordon and Wilfred Dewhirst also refers to the Anglo-Saxon Crepel, or covered way as the source of the name taken on by the gate, and that Crepel was still used in written references to the gate in the late 20th century. The authors do though dismiss the story of St Edmund as a story that can “hardly be taken seriously”.

Baddeley provides some excerpts from City records to illustrate the history of the gate. In 1297 is was ordered that “Crepelgate should be kept by the Wards of Crepelgate, Chepe and Bassieshawe”, and “At the Gate of Crepelgate, there were to be found at night, from the same Ward Within eight men, well armed; and from the Ward of Bassieshaw six men, well armed; and from the Ward of Colmannestrete, six men, well armed and Robert Cook and John le Little were chosen to keep the keys of the gate aforesaid.”

The gate required regular repair, and in “1490, Sir Edward Shaa, who had been Alderman of the Ward from 1473 to 1485 bequeathed five hundred marks for the purpose of repairing the Gate”.

The gate was well kept and guarded during the Wars of the Roses during the second half of the 15th century. This was the last time that the City wall was strengthened, and the brick work that was added to the City Wall can be still be seen in the stretch of wall by St Alphage, a very short distance to the east of the old location of the Cripplegate.

As with other City gates, it was used as a processional route, with Elizabeth I apparently using the gate as her access to the City on her journey from Hatfield to London after the death of her sister, Mary I on the 17th November 1558.

The gate was also used to display the bodies of those who had been executed as a warning to those passing through the gate.

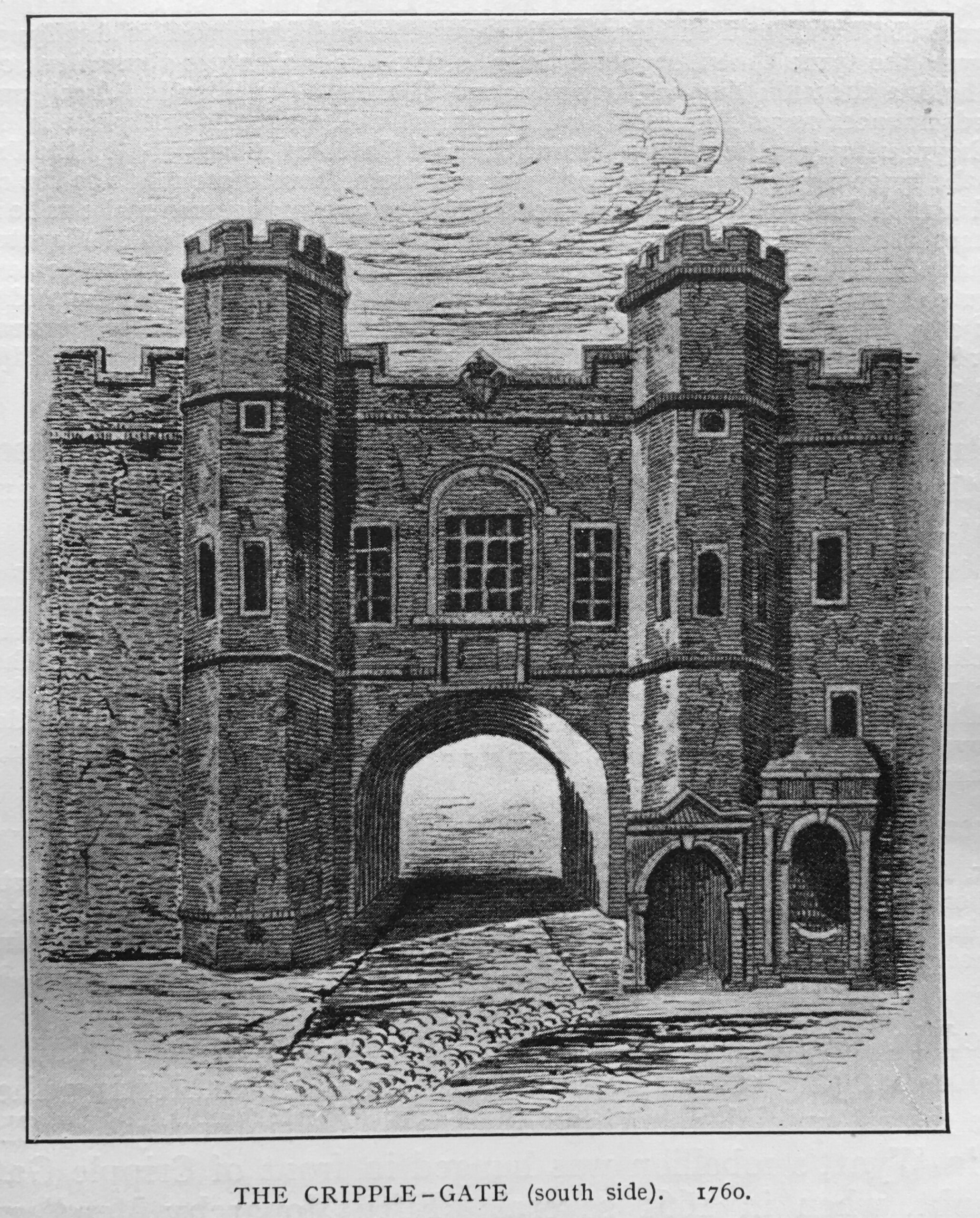

Cripplegate as it appeared in 1760 looking north from the City side of the gate, within Wood Street:

The above print from Baddeley’s book is dated 1760, although it may have been a view of the gate some years earlier, as by 1760 the gate was being described as in a poor condition. The carriageway through the gate was relatively narrow, and London had been expanding considerably to the north of the old gates and Roman wall which by the mid 18th century were no longer effective or needed as a defensive structure to protect the City of London.

Tolls were taken at the gate, but these were insufficient to keep up with the costs of repair, so in early 1760, the decision was taken to demolish the gate.

The City Lands Committee advertised for tenders to demolish and remove a number of the old gates, including Cripplegate, Aldersgate and Moorgate.

A Mr. Benjamin Blackden bought Cripplegate for £91 – buying the gate ensured demolition, and allowed the person buying the gate to keep a considerable quantity of building material.

The same Benjamin Blackden also paid £91 for Aldersgate and £166 for Moorgate.

On the 2nd of September 1760 newspapers were reporting that “Tuesday, the workmen began to erect scaffold at Cripplegate for pulling down that Gate.”

By the 31st of December, 1760, the Kentish Weekly Post was reporting that “Aldgate is quite pulled down, and Cripplegate is about two thirds down; and Moorgate, Aldersgate and Bishopsgate are to be pulled down forthwith.”

Demolition of the gate was completed in early 1761, and Wood Street then provided open access from the City to the northward expansion of London.

Lady Eleanor Holles School and Cripplegate are two lost features of Cripplegate Ward. Both very different, and in different periods of the Ward’s long history.

They have both left their mark in that the school is still functioning today, although in west London rather than the centre of the city, and Cripplegate, one of the City’s gates within the Roman Walls, that appears to have been named after an Anglo-Saxon word for a defensive, covered way, has left its name to one of the City’s most interesting wards.