Regular readers will know that as well as London, my father also took very many photos whilst cycling around the country during the late 1940s and early 1950s. For a mid-week post, I am visiting the location of one of those photos, which tells an interesting story of how land has been reclaimed, and the uses to which we have put that land. This is the view of Portsmouth from Portsdown Hill in 1949:

The same view in 2021:

There are a couple of details that confirm that this is the same view. Both photos have the electricity cables on the right disappearing over the edge of the hill, and in the distance the profile of the Isle of Wight is the same.

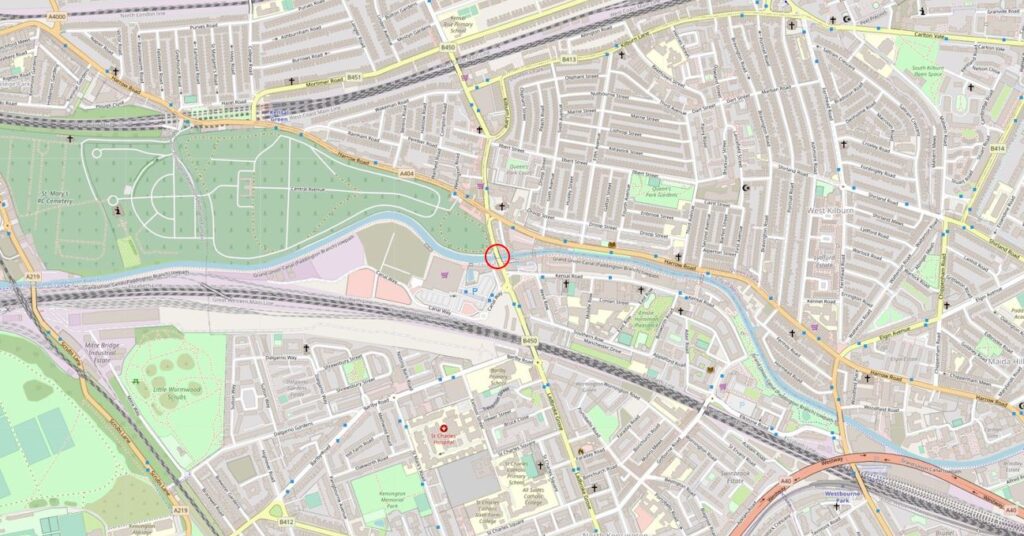

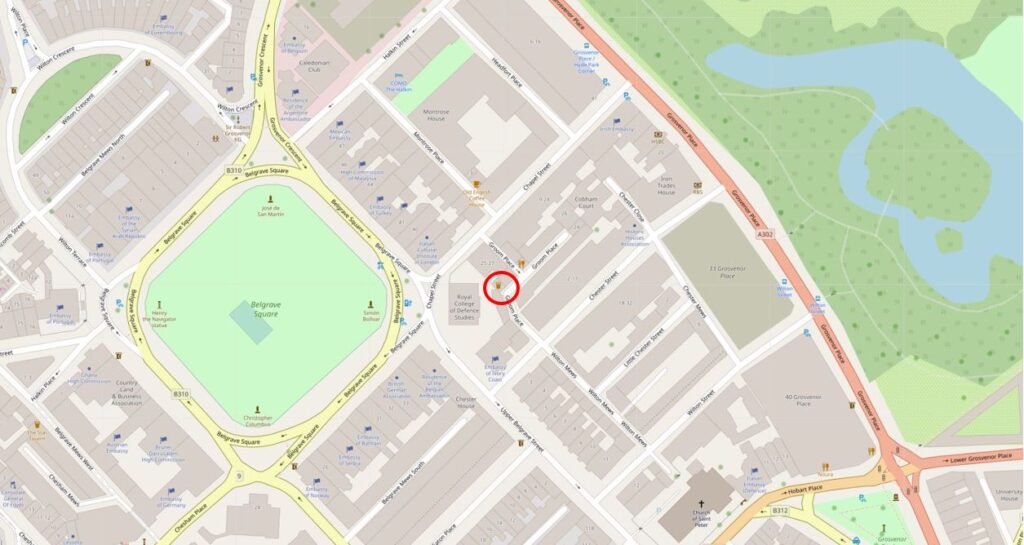

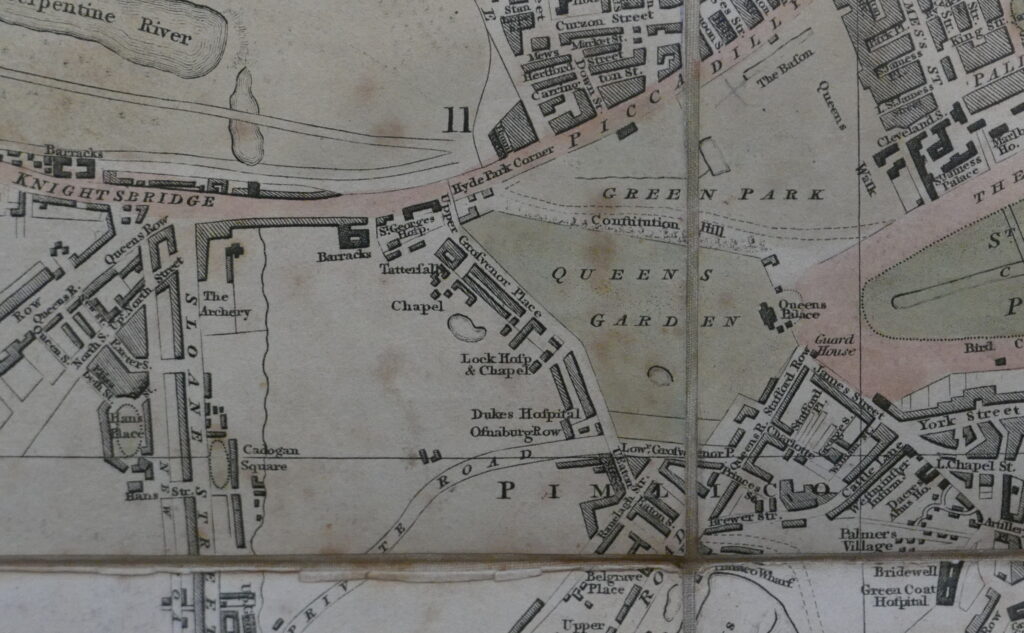

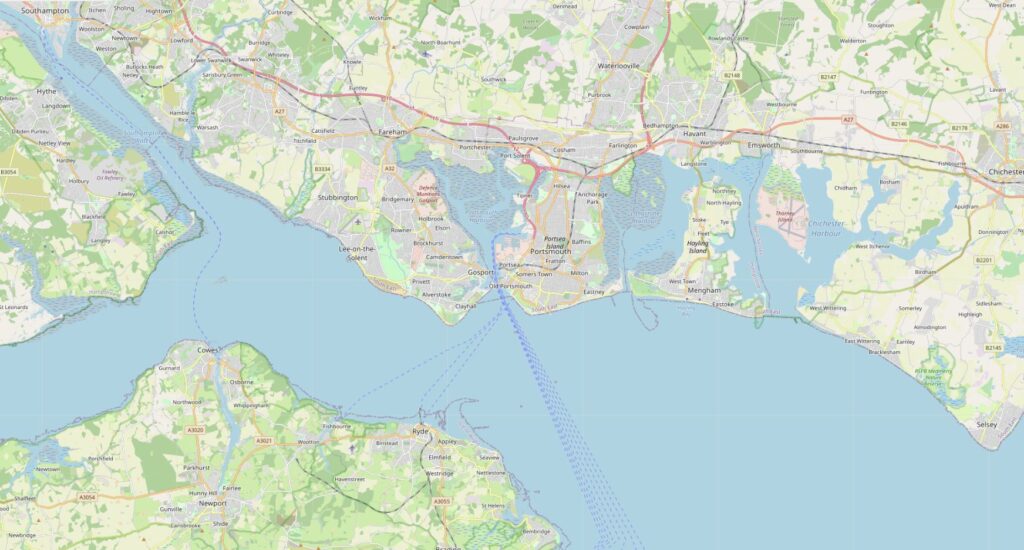

The location is important for the rest of the post. The following map is a wider view of the area. The Isle of Wight is lower left, the water is the Solent, the channel leading up to the top left corner is Southampton Water. Portsmouth is the block of land with water on both sides, in the centre of the map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

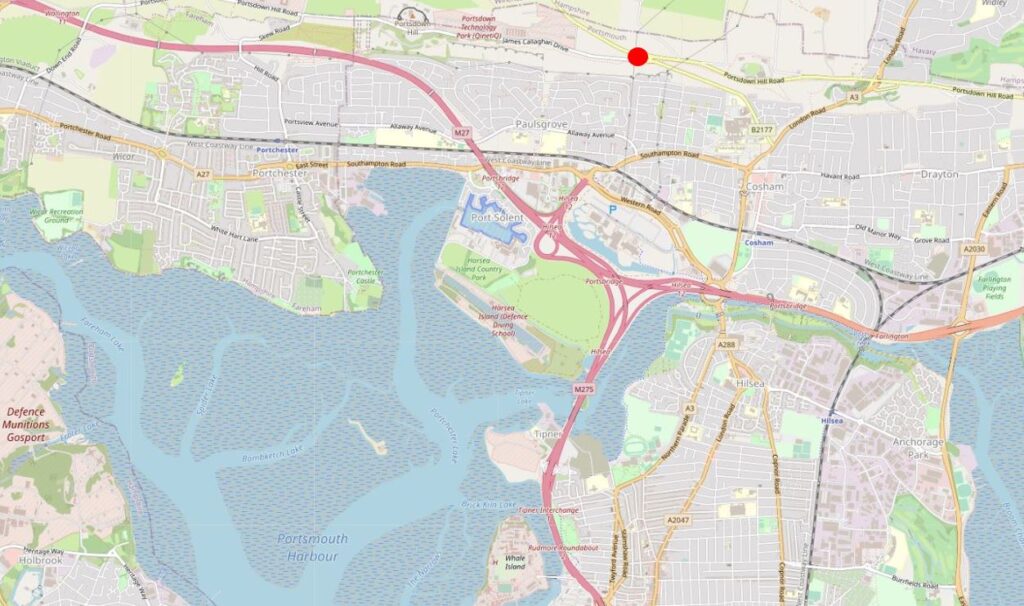

The following map is an extract from the above map, with the red circle marking the location from where both photos were taken (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

Portsmouth can be considered as an island as it is surrounded by water on all sides. Portsmouth Harbour to the west, Langstone Harbour to the east, the Solent to the south, and around the north of the island there is a narrow channel of water.

It is not very clear from the above map, but the place from where both photos where taken is on a hill. Portsmouth is generally flat and low lying with a maximum height of 6 metres. Directly behind Portsmouth is a chalk hill, known as Portsdown Hill, running east to west. The height at the location of the photo is 101 metres, so considerably higher than Portsmouth as illustrated in the photos.

Portsdown Hill is part of the geologic feature called the Portsdown Anticline.

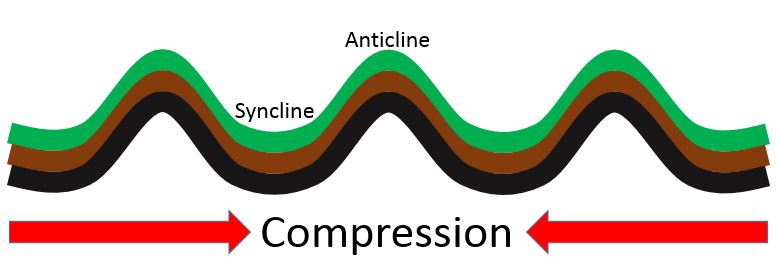

An anticline forms when the ground has been compressed from two sides, and the compression causes the land to rise and fall. An anticline is the part where the land has risen and a syncline is where the land falls. The following diagram illustrates the concept of an anticline and syncline.

The sides of an anticline sometimes erode over time, and also become exposed due to human activities, which has happened to the chalk of the Portsdown anticline, which I will show later in the post.

The anticline / syncline model explains much about the landscape of this part of southern England, with the hills on the Isle of Wight in the photo being part of the Sandown anticline, the ripples of anticlines and synclines forming the landscape up to Petersfield and Winchester, and further north, the Hog’s Back in Surrey, before flattening out to form the London Basin.

Human activity is often very visible with the construction of roads, housing, factories and warehouses, and in the two photos from Portsdown Hill we can see the impact of another form of human activity which has had a considerable impact on the waters of Portsmouth Habour since my father’s 1949 photo.

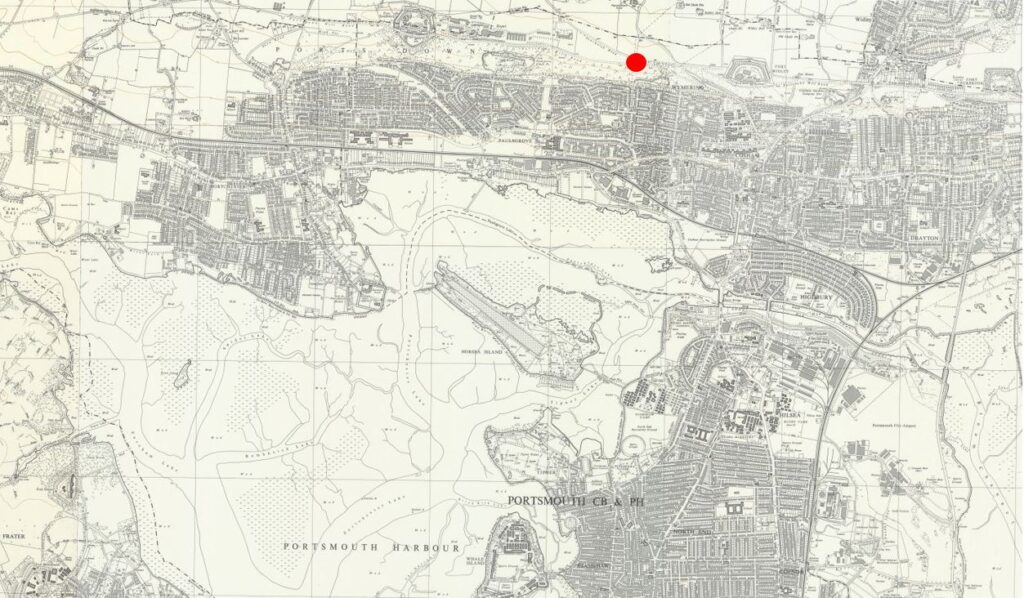

In the 1949 there is a large area of water in the foreground. In the 2021 photo this has disappeared. The following map extract shows the area in 1962. Again, the red circle indicates where the photos were taken from.

There is a large island (Horsea Island) in the north east part of Portsmouth Harbour (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

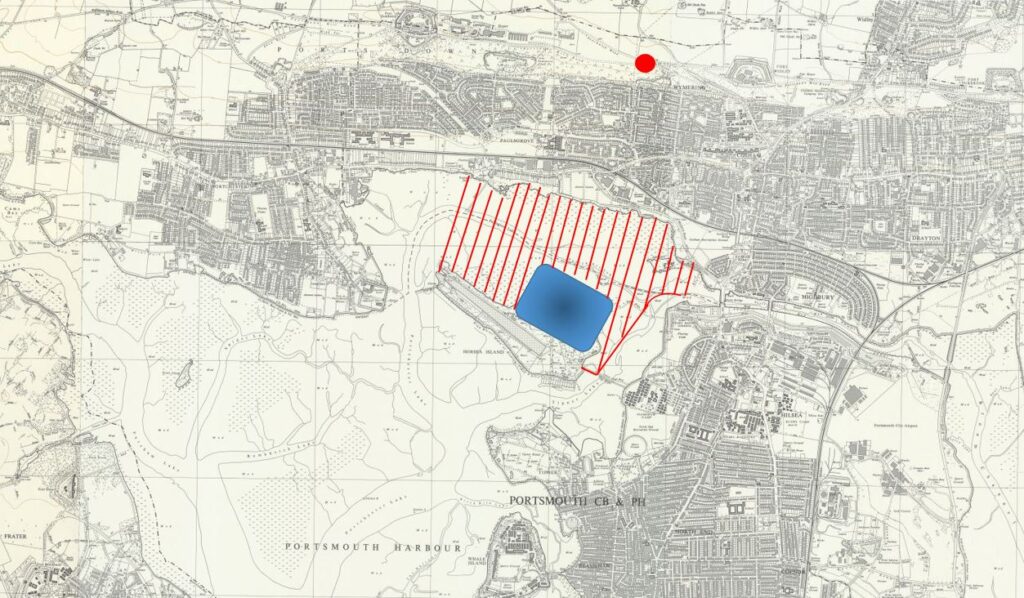

In the 1970s the area of land between Horsea Island and the mainland was reclaimed. The following map shows the reclaimed area.

Comparing the above map, with the map of the area in 2021 earlier in the post will show that the reclaimed area has been used for the M27 motorway, the M275 into Portsmouth, construction of Port Solent marina, along with housing, shopping, entertainment and buildings for marine businesses.

One large part of the reclaimed land was used as a landfill area for household waste. The area destined for landfill is shown in the above map highlighted in blue.

Even though the decision was made in the 1970s, it is still surprising that such a marine environment would be used for landfill. A number of old landfill sites on the coast are already, or at risk of erosion. This is already happening at an old landfill site on the Thames at East Tilbury.

The Portsmouth landfill site closed in 2006, and the site has now been grassed over, although vents can be seen protruding from the ground to vent the gasses from the decaying materials below.

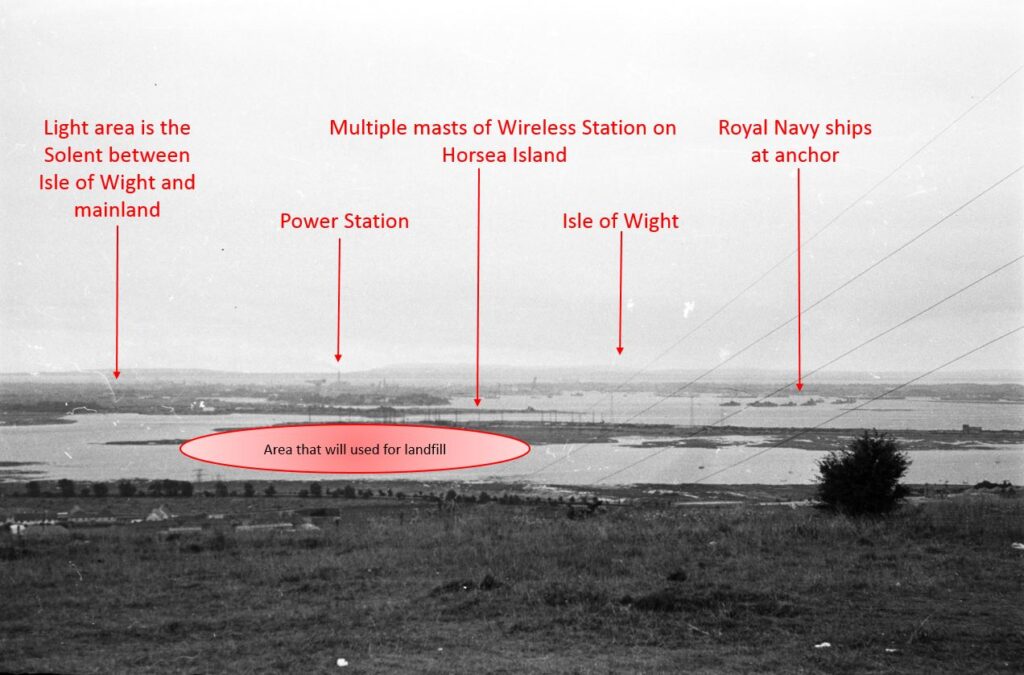

I have marked up my father’s 1949 photo with some of the key features, including the area that would become landfill.

The masts are part of a navy wireless station that occupied much of Horsea island. The island also had a torpedo testing range, which can still be seen as the long channel of water in the 2021 map earlier in the post.

The torpedo testing range was the result of earlier human intervention. Horsea Island was originally two islands – Great and Little Horsea. The admiralty purchased the islands in 1885, and they were merged into a single island using chalk excavated from Portsdown Hill. The enlarged island provided the space for the torpedo testing range which was eventually extended to a length of 1,000 yards.

The following photo from the same location shows the old landfill site as the large grass mound in the centre of the photo.

The Isle of Wight can be seen across the Solent and there is a tower rising to the right of the taller buildings of central Portsmouth.

This tower is the Spinnaker Tower located on the Portsmouth Harbour waterfront at Gunwharf Quays.

Gunwharf Quays is now a retail and entertainment complex, built on the site of HMS Vernon, an old part of Portsmouth’s naval base, and an area focusing on mine warfare and the development of torpedoes which provides a link with Horsea Island. HMS Vernon was decommissioned in 1986.

Construction of Gunwharf Quays started in 1998. It was a complex engineering and construction process as much of the new site would be built over tidal mudflats and one of the largest marine decks in Europe was built to support much of the new building.

Construction of the Spinnaker Tower started in late 2001, based on a design chosen from three designs put to a vote by the residents of Portsmouth. The design is intended to emulate the billowing out of a spinnaker sail to reflect Portsmouth’s marine heritage.

At the top of the Spinnaker Tower is a viewing gallery, which I visited a number of years ago. The height of the tower provides a spectacular view over the surrounding area. In the following photo, the view is back towards Portsdown Hill and I have marked the site of the 1949 photo with a red arrow.

The white of the exposed chalk can be seen just to the right of the arrow, with a much larger area to the left. This is the underlying chalk of Portsdown Hill which has been exposed by both weathering and erosion over time, as well as human quarrying.

The Portsmouth naval base as well as the historic dockyard occupy much of the foreground of the photo.

The large ship nearest to the camera is HMS Warrior. Built in 1860, HMS Warrior was powered by both steam and sail, and was Britain’s first iron hulled, armoured naval warship. The most technologically advanced ship of her time.

Follow up from the funnels of HMS Warrior and HMS Victory can also be seen. The Historic Dockyard is also home to the Mary Rose, the flagship of King Henry VIII, which sank in the Solent in 1545, and raised from the seabed in 1982.

Looking in the opposite direction, the Spinnaker Tower provideds a superb view over the Solent and the entrance to Portsmouth Harbour.

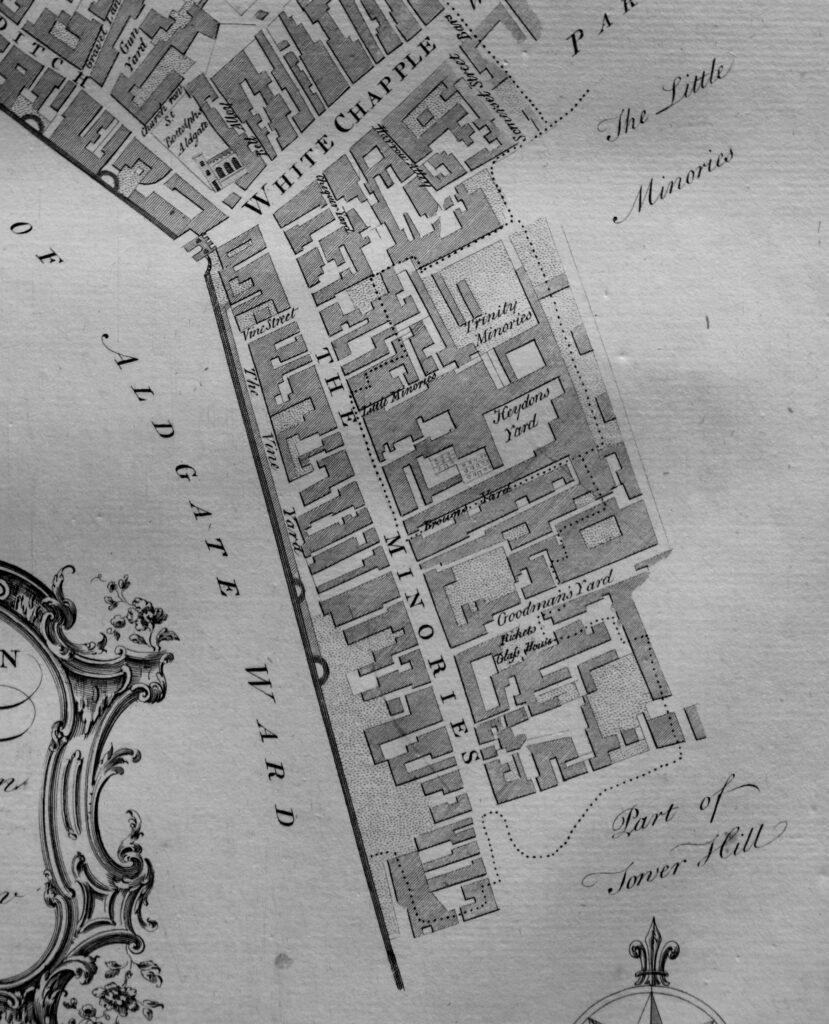

In the above photo, the area to the left of the harbour entrance is called Portsmouth Point, also known as Spice Island.

Today, there are a couple of brilliant pubs facing onto the harbour entrance, however in the past, Portsmouth Point / Spice Island had a reputation for drunkness, prostitution and crime, with press gangs roaming the streets.

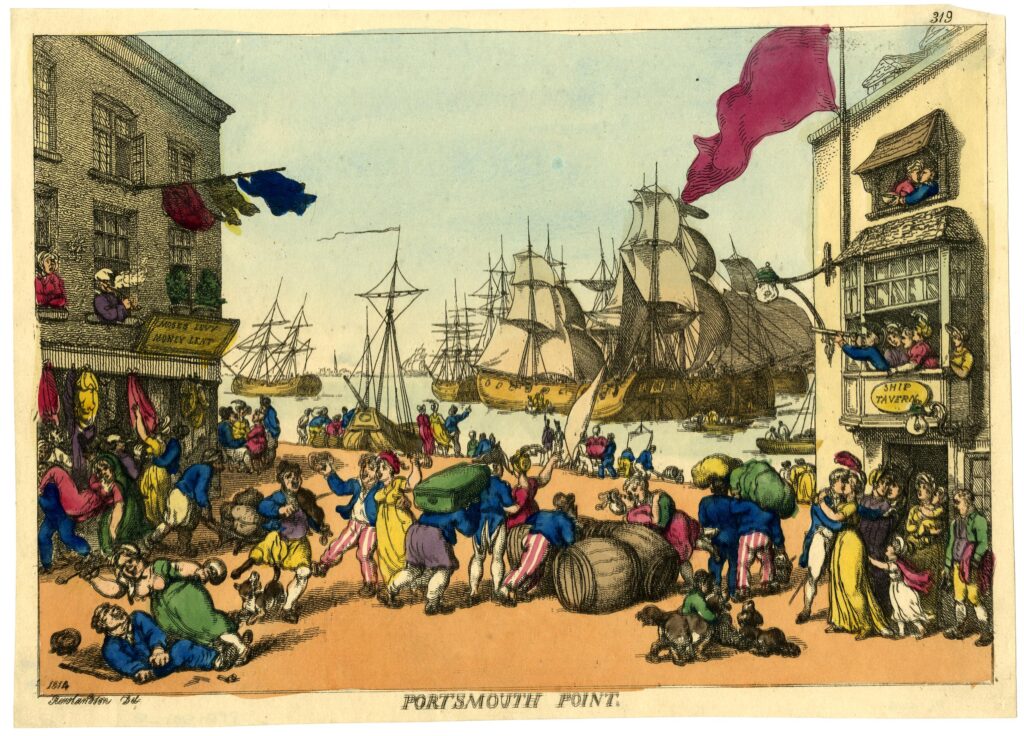

Thomas Rowlandson produced the following satirical print of Portsmouth Point in 1814.

The view is looking out towards Portsmouth Harbour where numerous ships are moored or with their sails up. General confusion and chaos reigns on the Point with sailors just returned or about to leave (a sailor is saying goodbye to his family in the doorway on the right, whilst in the window above an officer is looking towards the harbour with his telescope).

The power station chimney seen in the 1949 photo was just to the left of the above photo, the area is now covered with housing.

Portsmouth harbour opens out into the Solent, the water that runs around the north of the Isle of Wight.

Although the Isle of Wight is now an island, this was not always the case. The Solent was once part of a large river system that drained part of southern England, including Portsmouth, Langstone and Chichester Harbours, along with Southampton Water.

The west of the Isle of Wight was connected to Dorset during the time of the Solent river system, however the land was breached around 7,000 years ago as sea levels rose following the end of the last glacial period and melting of large sheets of ice.

There is so much history to be discovered around Portsmouth. In the above photo, there are some round objects visible in the sea to the left of the photo. These are what have become known as Palmerston Forts, or Palmerston Follies:

These were built between 1865 and 1880 following a Royal Commision that raised concerns regarding the risk of a French invasion. They were intended to defend Portsmouth from an attack from the east.

They were named after Lord Palmerston who was Prime Minister at the time, and who championed the idea of the forts. They became known as Palmerston Follies as they were never used as a French invasion never materialised, and they quickly became outdated following advances in weapons technology.

Three additional land based forts were also built along Portsdown Hill which can still be seen when travelling along the road that runs along the top of the hill.

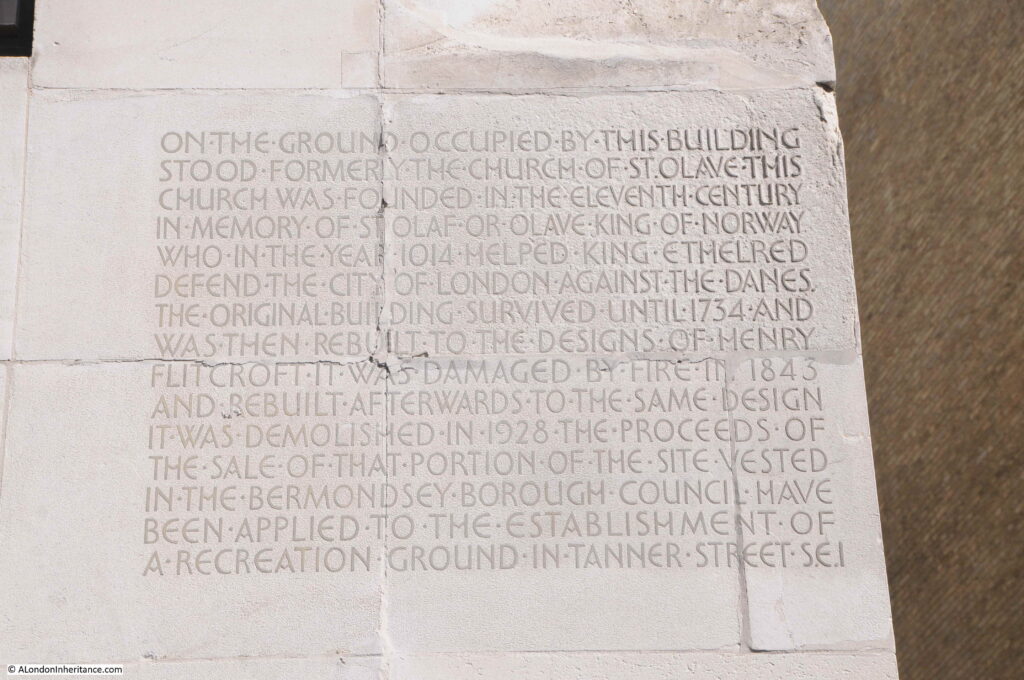

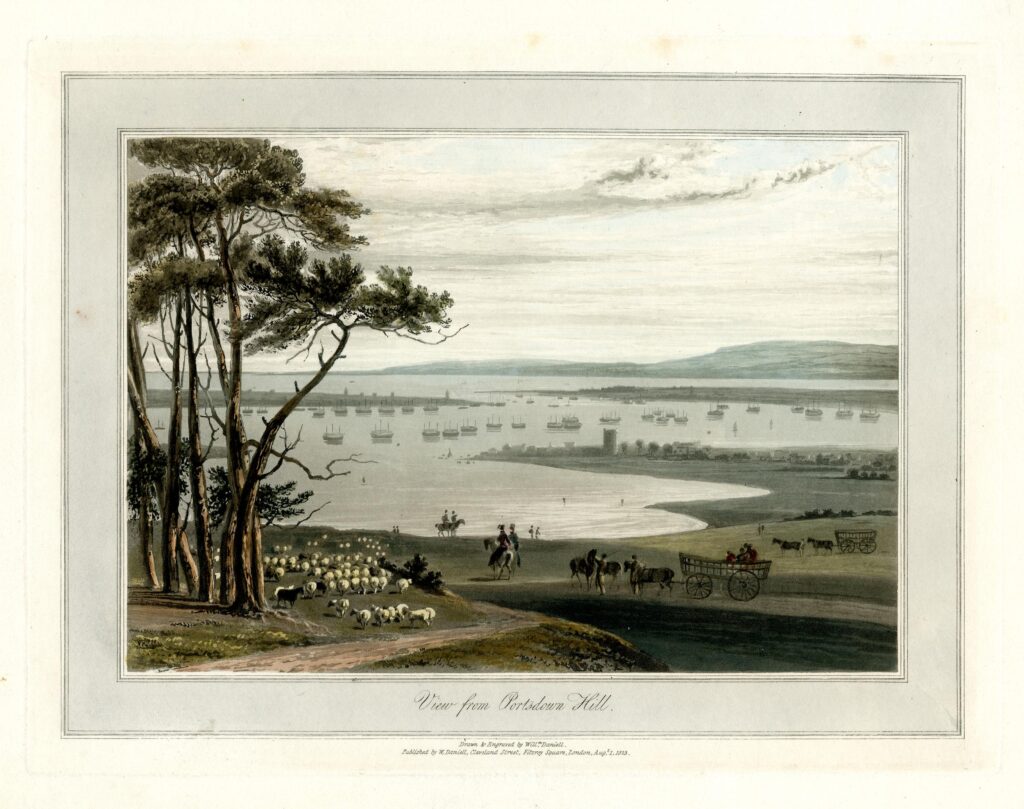

The following print from 1823 shows a view from Portsdown Hill, further to the west of my father’s 1949 photo (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

There is a tower like structure in the centre of the print, which can also be seen to the right of the 1949 photo. The tower is the Norman keep of Portchester Castle at the northern end of Portsmouth Harbour.

Portchester Castle was originally a Roman fort, built in the 3rd century as one of a number of shore forts to defend the area against Saxon raids.

The old Roman fort seems to have been occupied from the ending of the Roman period to the Norman conquest, when the site became a Norman castle, with a 12th century keep. The castle continued to be in use and further fortified due to its strategic position, and what seems to have been an almost continuous threat of invasion by the French.

Charles I sold the castle to a local landowner in 1632, and for periods during the next two centuries, the castle was rented to the Government as a prison to hold prisoners of war, including during the Napoleonic wars of 1793 to 1815, when the castle was home to thousands of prisoners.

Portchester Castle is still owned by descendants of the landowner who purchased the castle from Charles I, and is now managed by English Heritage.

Portchester Castle from the air, facing onto Portsmouth Harbour:

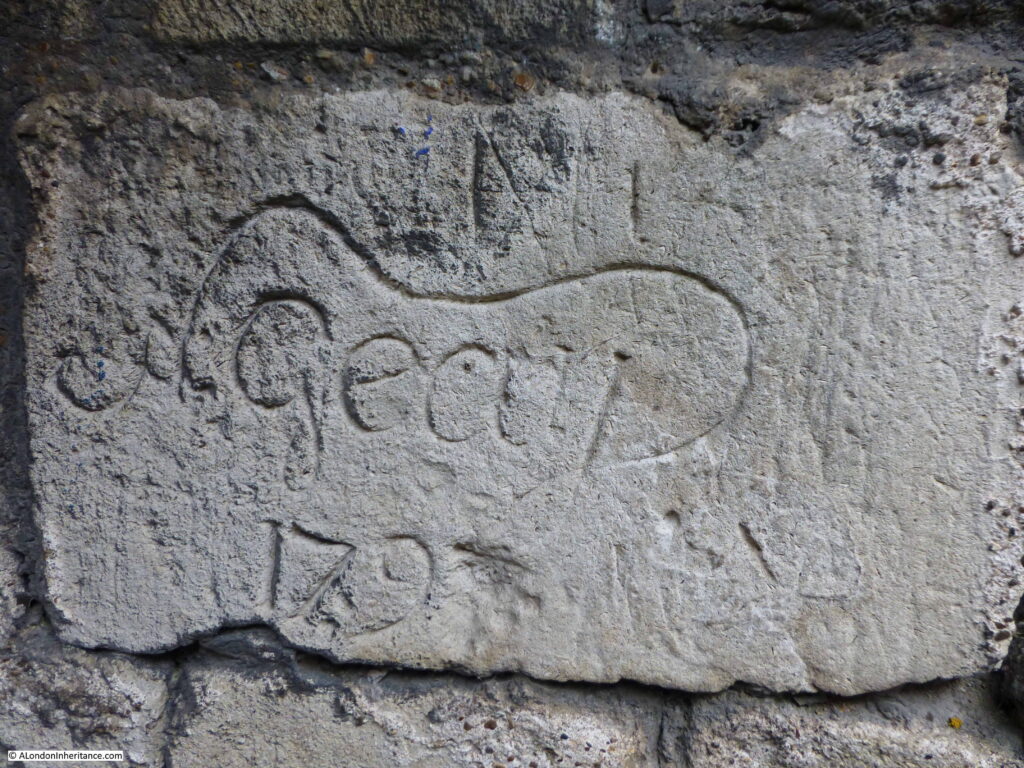

Some of the prisoners left their mark with graffiti on the castle stone:

The view from Portsdown Hill has changed considerably since 1949, however the view still includes a fascinating sweep of historical and geological time, and there is far more to be discovered than I have been able to cover in a single post. The view tells the story of how the land developed, and what we have done with that land.

The 1949 photo was taken by my father on one of his cycling trips out of London, Youth Hostelling with friends from National Service. Other locations I have so far covered on this route along the south of England include:

Chichester Market Cross And The First Fatal Railway Accident

Salisbury – Poultry Cross, High Street Gate And Cathedral and,