There are names that keep coming up whilst exploring London’s history, and this week’s post is about one of those names, Sir Polydore de Keyser.

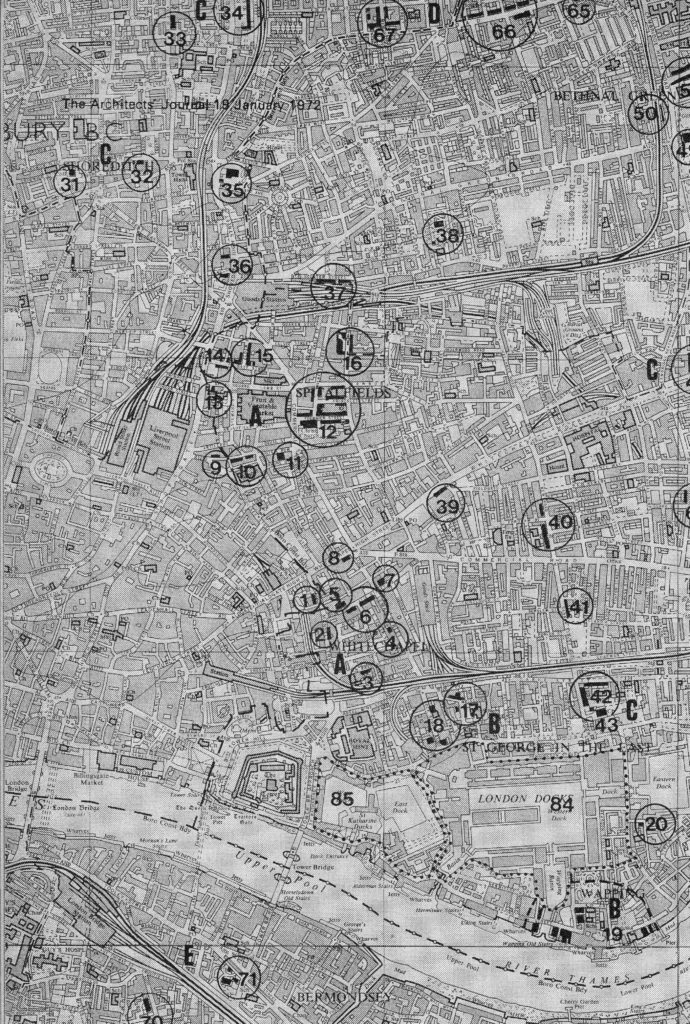

I first came across him whilst writing about the area directly to the north of Blackfriars Bridge. Then a few months ago, my blog started to get a number of redirects from the Guardian website from an article about the Supreme Court judgement on Brexit – a judgement in which de Keyser’s hotel was referred to several times. I also recently found Polydore de Keyser again during a walk through Smithfield.

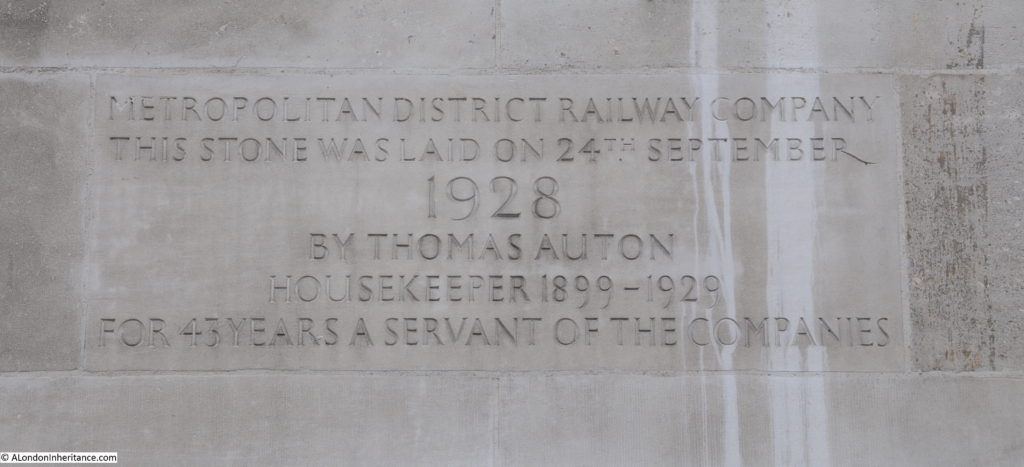

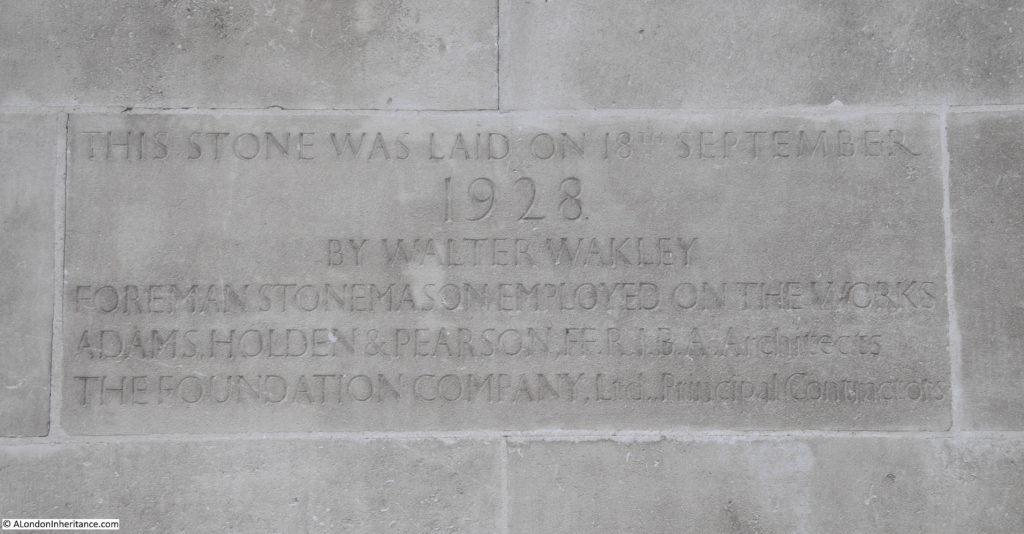

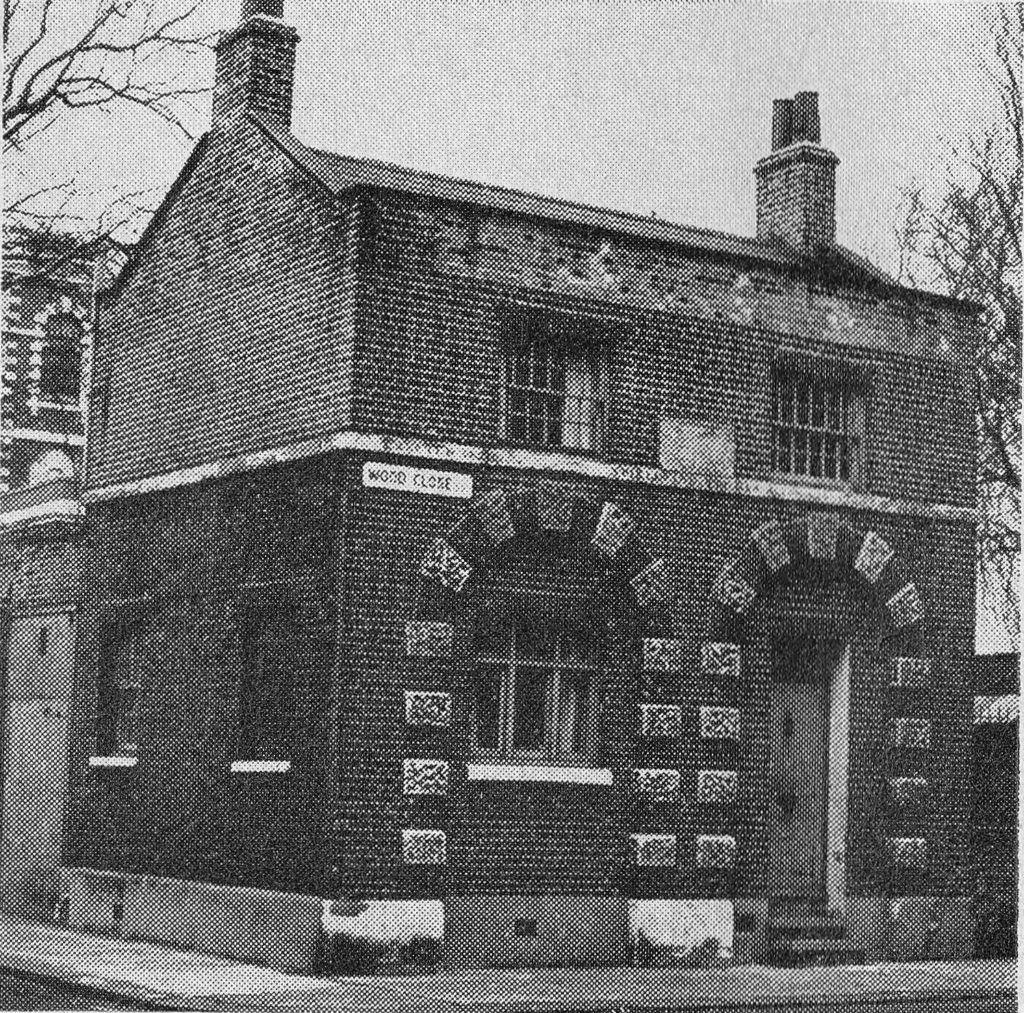

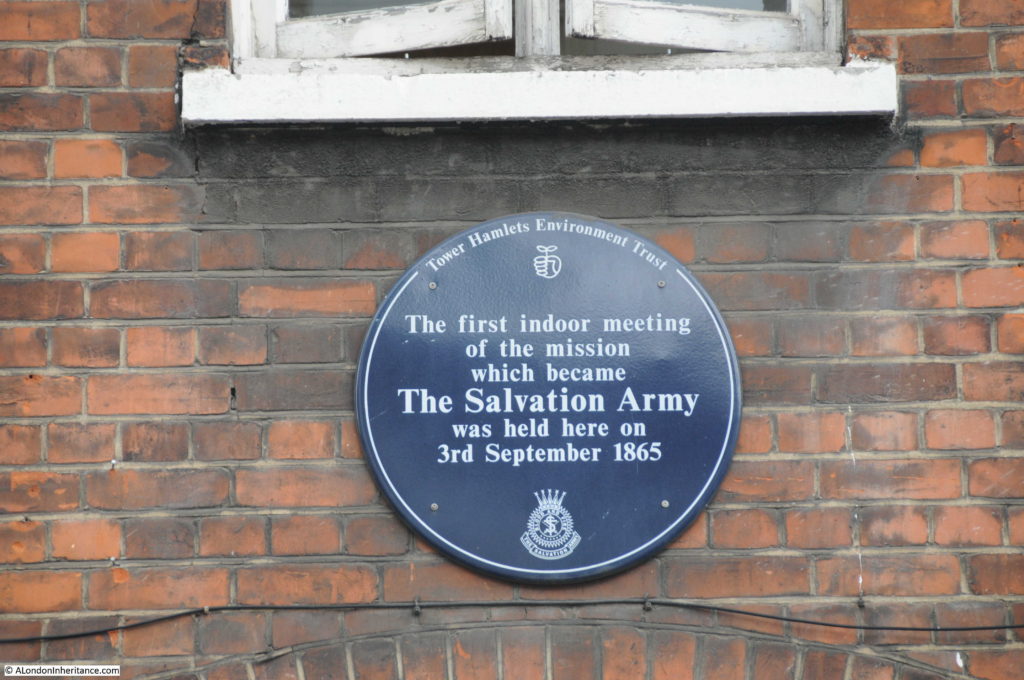

I was taking photos of the market buildings as the area will undergo considerable change in the years to come, when I saw a plaque I had not noticed before on the corner of a building at the junction of West Smithfield and Snow Hill (the corner of the building facing the camera on the right of the following photo, the plaque is just below the round window)

The plaque records that the market was opened by Sir Polydore de Keyser on the 7th November 1888:

So who was Polydore de Keyser? There does not seem to be much written about him, so I thought a read through some old newspaper archives might shed some light on this interesting character with the foreign sounding name, and from the above plaque was Lord Mayor in 1888.

I found the fascinating story of an immigrant from the Continent who reached the highest of offices in the City of London, but who also faced continual criticism because of his origins.

Polydore de Keyser was born in 1832 in the Belgium town of Termonde (the French name or Dendermonde in Flemish) in the north west of Belgium between Brussels, Antwerp and Ghent.

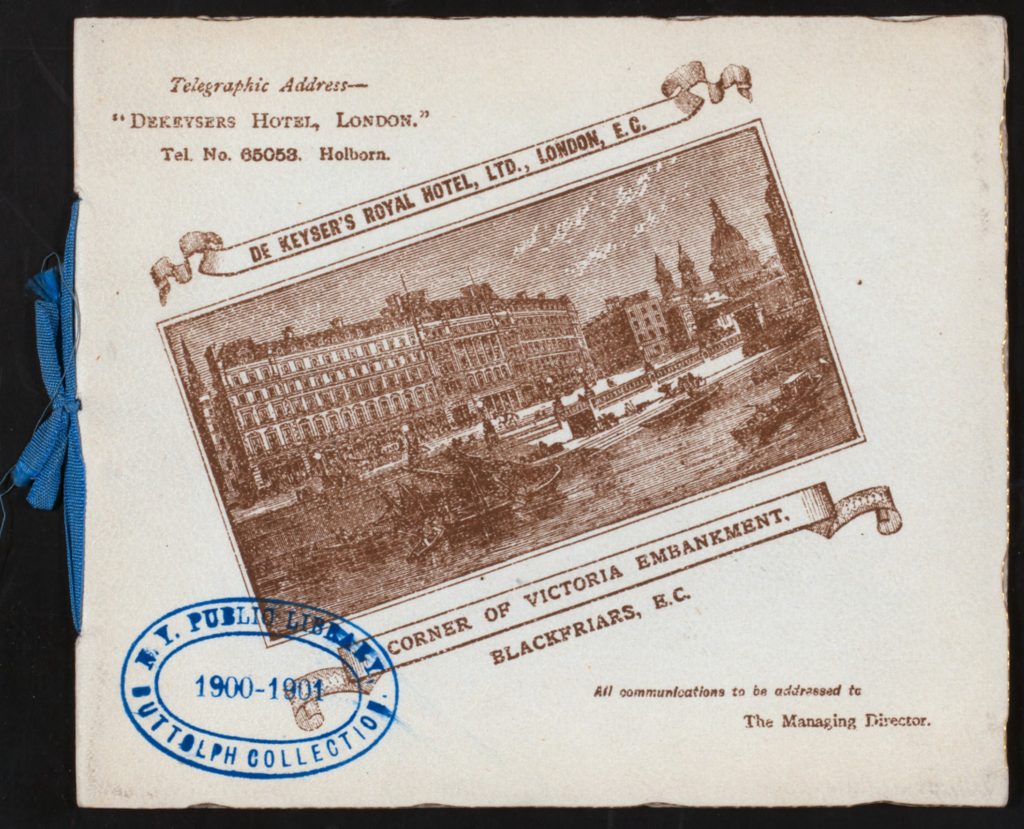

He moved to London in 1842 with his father, Constantin de Keyser and mother, Catharina Rosalia Troch. His father had been a teacher in Belgium, but on arrival in London he purchased a hotel which he renamed de Keyser’s Royal Hotel. A strange career change and I have been unable to find any references as to why the de keyser’s moved to London and took up the hotel business.

One of the first references to Polydor de Keyser are in newspaper adverts across the country from 1856. He was an importer of the German drink “Maitrank” and his advert in the Newcastle Journal on the 19th July 1856 reads:

“THE LIQUID HEAVEN of the Germans – Who that has tasted the delicious ‘Maitrank’ or May drink of Germany, can ever forget it. Poetic in name, and inspiring in its essence, it is the wine of wines. the exquisite flavour of that lovely mountain flower – the Waldschloschen appears to be heightened by its being wedded to the juice of the grape, and may well the refined connoisseur hang upon the memory of its tempting fragrance. The worshippers of this nectar have become almost frantic with delight by the announcement that a Herr Polydore de Keyser has succeeded at length in imparting to it the additional charm of effervescence, a right sparkling attribute, which it alone required to bring it to perfection”.

Orders were requested to be sent without delay to either Polydore de Keyser of 24 Cannon Street, London, or to his agents across the country. Maitrank could be purchased for 72 shillings per dozen.

Also in 1856, Constantin left the running of the hotel to his son Polydor.

He does not seem to have been involved in any activities that justified a newspaper article for a number of years, he was running his hotel and probably getting involved in societies and good causes in his local area and that justified an interest due to his background.

In 1866, at a meeting in St. Ann, Blackfriars, Polydore de Keyser subscribed £2, 2s to a testimonial to acknowledge the service of Mr. R.E. Warwick who had “for many years past has endeavored to obtain a better distribution of the charges for the relief of the poor in Unions”. At the meeting, other subscribers included the Mayor and Alderman so de Keyser was moving amongst those who managed the running of the City.

A year later, de Keyser was perhaps using his European contacts as he was acting as a steward for an anniversary celebration for the German Hospital in Dalston, held in the London Tavern on Bishopsgate Street.

Polydore de Keyser already had a hotel in Blackfriars, the hotel that his father became the proprietor of when he arrived in London. This was the Royal Hotel, in Chatham Place, New Bridge Street, Blackfriars.

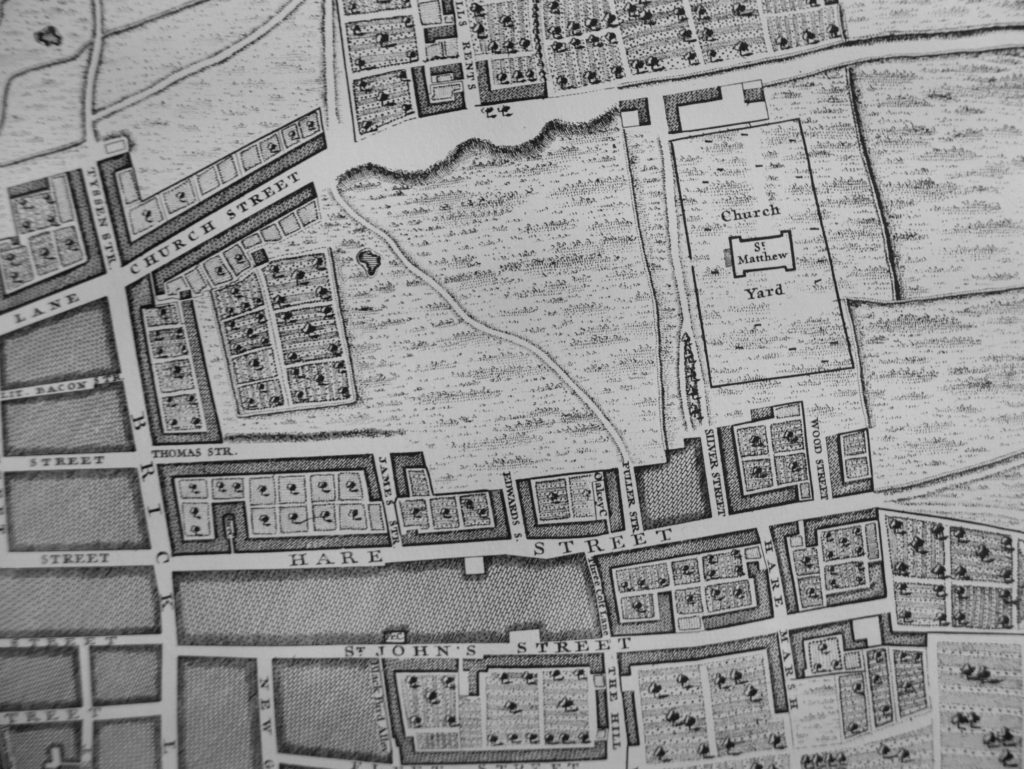

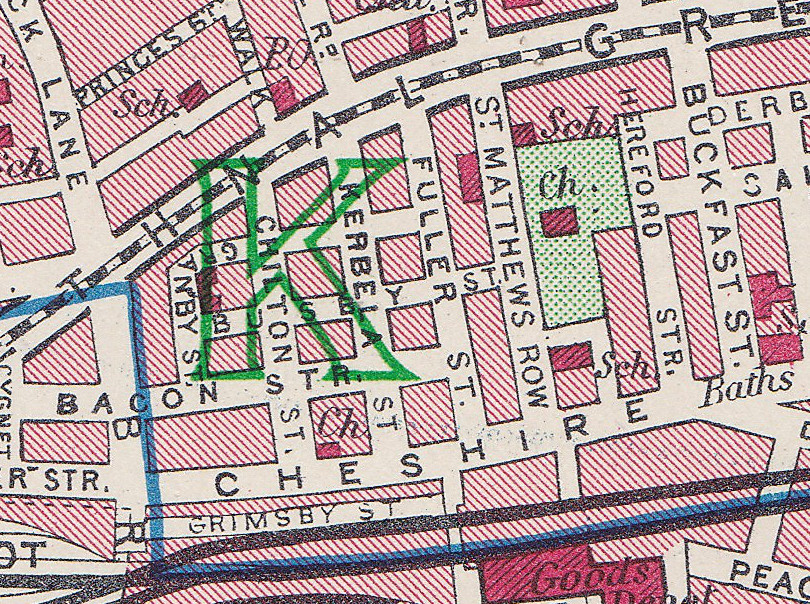

Chatham Place was the space at the northern end of Blackfriars Bridge, between the bridge and New Bridge Street. The following map shows the location in 1832:

I cannot find the exact location of his original hotel, however I suspect it was part of the block on the left of Chatham Place as this is where his new hotel would be built.

Newspaper reports help provide an idea of the way local commissioners and wards worked, and how complaints could be resolved. In the London City Press on the 26th March 1870 there is a report that he was summoned before the Commissioners of Sewers.

He had been summoned to explain why he had not carried out a number of works to his hotel to make it safe. There was a crack in the hotel but it had been filled in years before and had not changed since. The charge was thrown out on the grounds that Alderman Stone found the building was not dangerous and that the complaint by a Mr Power was malicious as de Keyser had apparently made an earlier complaint against him to the Commissioners of Sewers.

By 1872, de Keyser was ready to make his mark on Blackfriars and an article in the Morning Post of the 6th May 1872 announced the plans for his new hotel:

“IMPROVEMENTS AT BLACKFRIARS – In the background of the Victoria Embankment there are many ugly spots, which can only be beautified by the enterprise of private individuals, the Metropolitan Board of Works having no authority over the unsightly looking places alluded to. One of the chief eyesores is the ungainly group of gasometers at Blackfriars Bridge, and it would certainly be a pity if such monsters should remain in their current position. It is gratifying to know that they will cumber the ground where they are reared but a short time longer, as a very enterprising and highly respected Belgian, Mr. Polydore de Keyser, of the Royal Hotel at Blackfriars, now a citizen of London, has matured a vast plan by which a hostelry such as can only be paralleled by that called ‘grand’ at Paris will be shortly added to the few handsome buildings to be seen along the river front. This hotel, when completed, will extend from the corner of William Street, along a curved frontage of 380 feet, on to the entrance of the ground at the back of the embankment, sweeping away the gasholders now there.

The hotel, the design for which is in the modern French style, will have an entrance from the embankment into a spacious courtyard, into which carriages can drive, whilst the ground floor and basement will contain a series of elegant shops. The hotel is to be fitted up on the Continental system, with a spacious and handsome dining room as well as another room facing the embankment. Mr Gruning is the architect, and Messrs. Trollope and Sons the builders. it is anticipated that it will be completed and opened within a period of 21 months. On Saturday the foundation-stone was laid, in the presence of a large company of ladies and gentlemen by Miss Wich, daughter of the Belgian Consul, and at the dinner which followed, Sir Benjamin Phillips who was in the chair, wished every prosperity to Mr. de Keyser, a sentiment in which his numerous friends most cordially joined.”

The hotel opened in 1874 and the following print shows the hotel in that year.

An interesting feature appears to be a tunnel from the edge of the river allowing deliveries to be made by river, then transported into the hotel underneath the road. If you click on the photo to enlarge, you will see there is a man rolling a barrel into the tunnel.

This later photo from the southern end of the bridge also shows the hotel curving round from the Embankment.

The Morning Post on the 7th September 1874 carried the following report of the opening of the hotel:

“THE NEW ROYAL HOTEL – The latest addition to the palatial hotels with which London is now adorned is to be found in the new Royal Hotel, at the City end of the Victoria Embankment, which is to take the place of the Royal Hotel in Bridge Street, so long kept by Mr. Polydore de Keyser, representative in the Common Council of the Ward of Farringdon Without. This hotel, now completed, was open to the friends of Mr and Mrs de Keyser on Saturday, and after a pretty thorough inspection of this magnificent building, it may be safely said that in many respects it is altogether unequaled in London or in any of the great Continental cities, not excepting the famous caravanserai in Geneva, Interlaken, and other places to which tourists resort in such numbers. As Mr de Keyser has had ample experience in providing for his numerous foreign and English visitors, and as the internal arrangements have been carried out after his own designs, it may be safely said that nothing is wanting to make a stay in the new hotel agreeable. The view from the front windows over Blackfriars Bridge and the Embankment and over the busy Thames extending to London Bridge on the one hand and Westminster on the other, is most remarkable, and will give anyone a just idea of the immense traffic constantly going on in the metropolis.

The restaurant is capable of seating 400 visitors, and on the five floors there is a vast number of rooms either for bed chambers or sitting rooms. Those on the lower floors, which may be presumed to be state apartments, are fitted with exquisite taste and with every comfort; while in the upper apartments are equally calculated to make a stay in every way agreeable. All the adjuncts of a first class hotel, such as billiard, smoking, reading and drawing rooms for ladies, are provided, and the lifts and arrangements for ventilation are on the most approved principles. On Saturday Mr. and Mrs De Keyser welcomed at a dinner and subsequent concert some 400 of their friends, who heartily wished them success in their great undertaking. The new building, large as it is, is but half of that which is intended, the other portion being destined to occupy, with some slight deviations, the site of the buildings in which business has hitherto been carried on.”

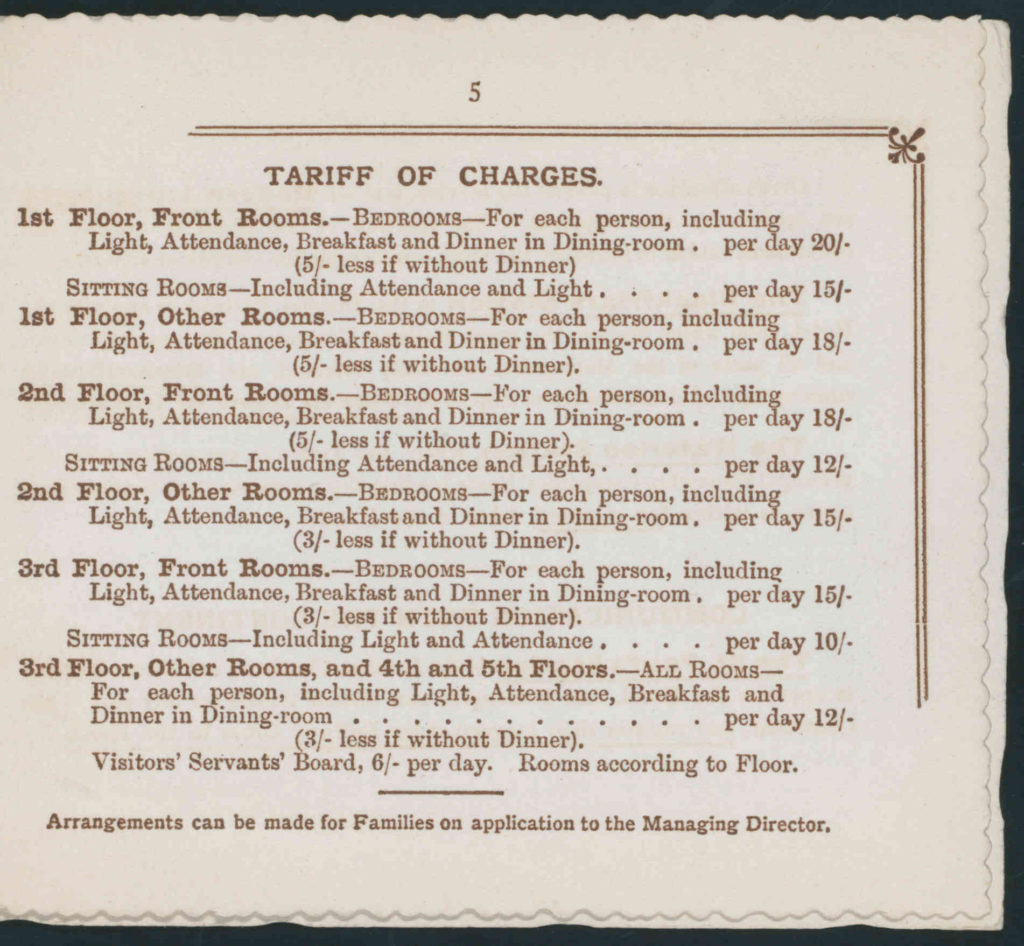

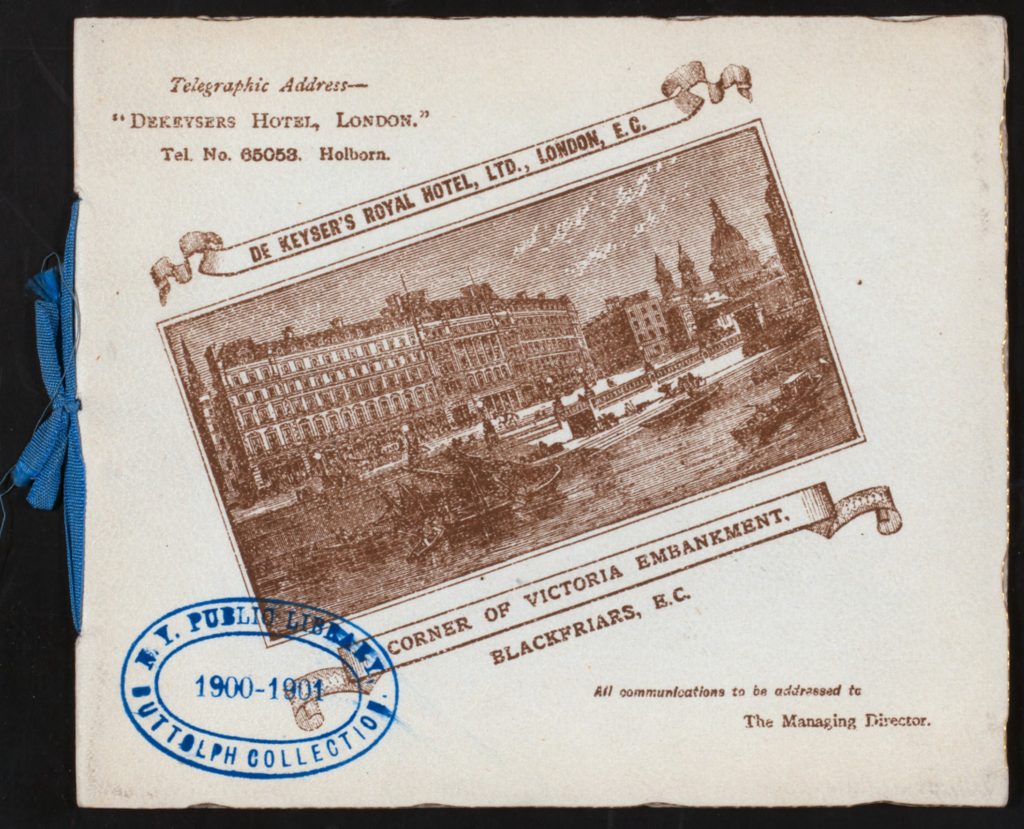

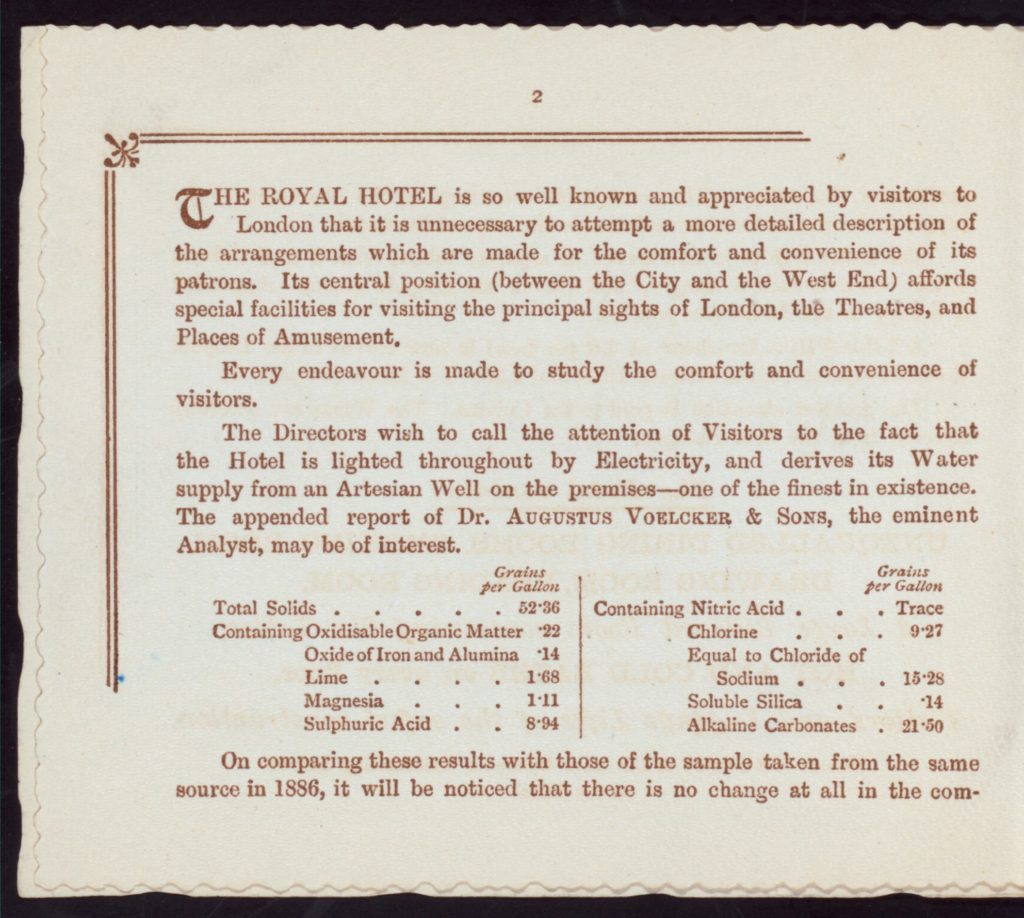

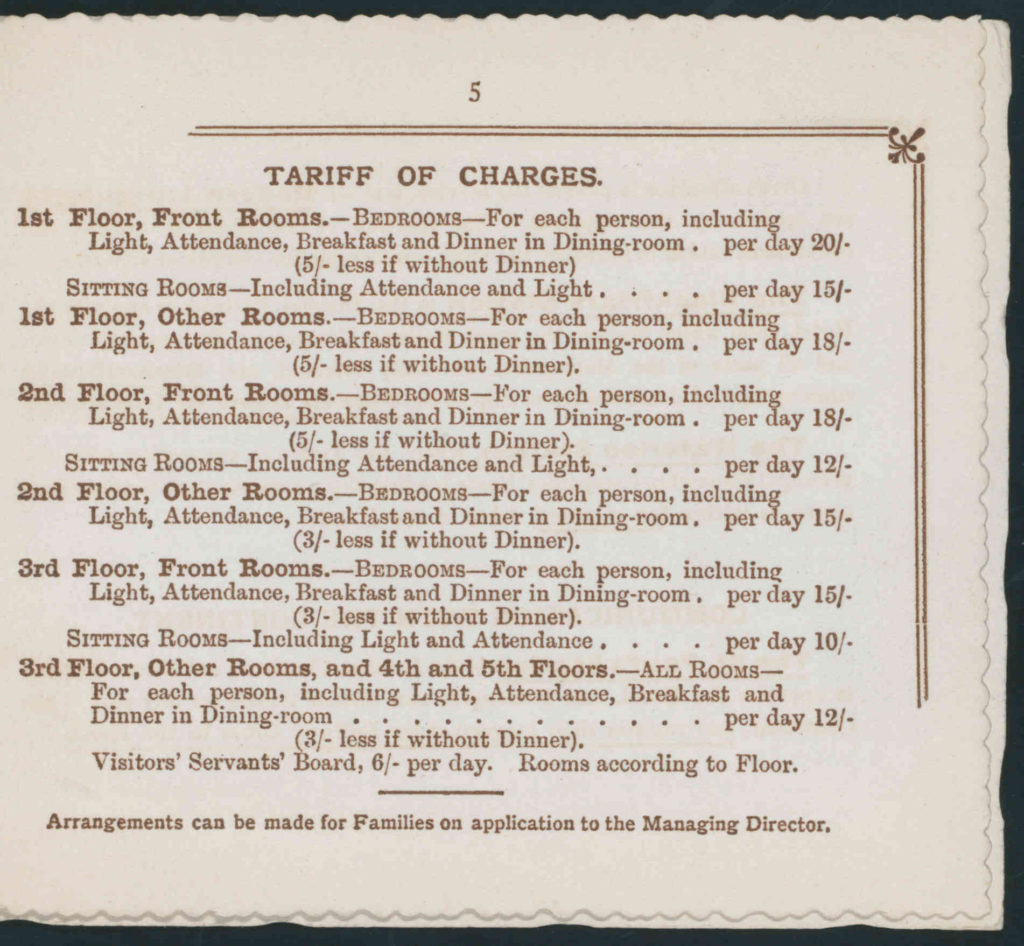

The following pages from an 1891 brochure for De Keyser’s Royal Hotel provide an idea of what would await a guest during their stay at the hotel. (From New York Public Library Digital Collections – free to use without restrictions)

De Keyser seems to have been involved in numerous other activities as well as running his hotel. In 1875 he was elected to the Committee of the Hotel Keepers’ Association and in 1876 he was on the London Executive Committee for the organisation of the British exhibits at the Brussels Exhibition. It was at this exhibition that he would meet the Prince of Wales who declared himself “well pleased with the British section in all respects”.

I get the impression that de Keyser was a master of the art of networking.

In 1877, de Keyser was elected as a Common Councilman of the Ward of Farringdon Without and in 1882 he was elected as an Alderman of the same ward, although this was not an appointment to which everyone agreed. There were two protests against de Keysers appointment, one by Mr. ex- Sheriff Waterlow who was the unsuccessful candidate and one by Mr. john Hill and other electors of the ward, on the grounds that de Keyser was an alien born, and that he was the holder of an innkeepers licence.

To address these protests, a special meeting of the Court of Aldermen was held at the Guildhall on Tuesday 20th June 1882. He had won the election by over 300 votes so he had won the election fairly and clearly. The final decision was delayed until the first week of July when the protests that he could not be an Alderman as being alien born and holding an innkeepers licence were overruled and de Keyser took his seat as an Alderman of the Ward of Farringdon Without.

An example of the activities that de Keyser took part in through his role as an Alderman is a report of a meeting of the inhabitants of the Precinct of St. Brides, held in St. Bride’s Church on Thursday May 22nd 1884 when de Keyser was in the chair. The meeting was held to discuss the impact of the London Government Bill, part of the Municipal Corporations Act of 1882 that was continuing the consolidation of powers from the various Vestries and Wards that had been the traditional holders of local power across London.

The meeting resolved that “In the opinion of this meeting the Municipal Bill for London, if it becomes law, would be prejudicial to the interests of local self-government, and would create a vast system of centralization involving increase of rates, with no compensatory increase of efficiency.”

Despite the meeting’s resolution it was powerless to prevent the gradual centralization of powers across London.

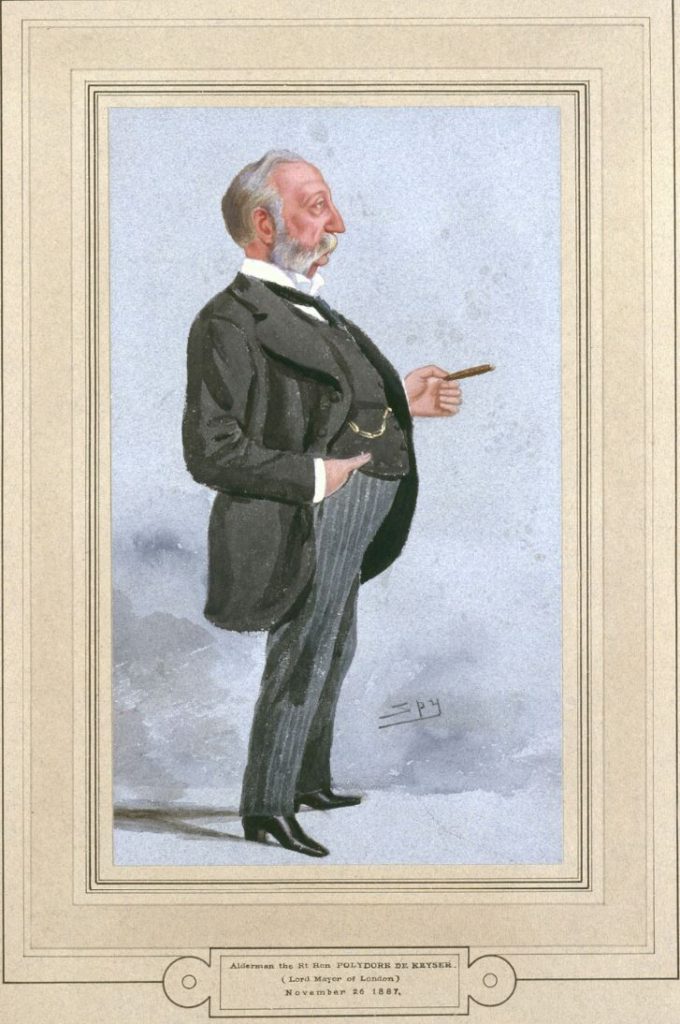

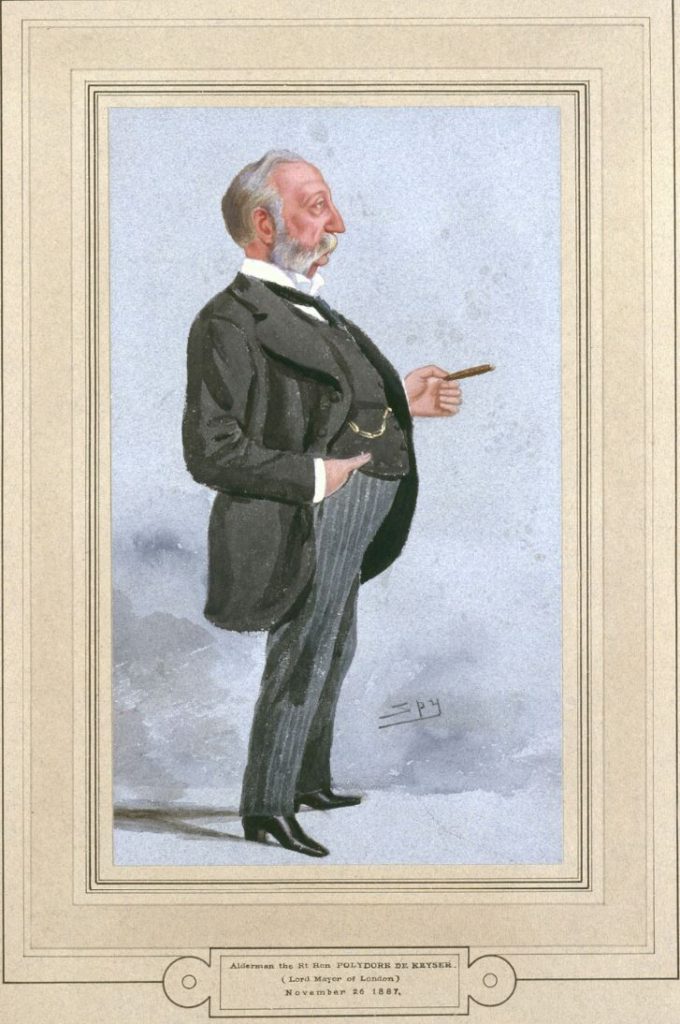

In 1887 de Keyser reached the pinnacle of City of London governance when he was elected Lord Mayor, however the election was somewhat contentious and newspaper reports highlight the fact that he was an “alien” he was “born in Belgium” and that he was “the first Roman Catholic who has been elected to the civic chair since the Reformation”.

One newspaper report stated that “The gentleman who took his seat on Tuesday in the civic chair of the City of London has before him a somewhat difficult task. The difficulty arises from the fact, principally, that Mr. Polydore de Keyser is a foreign born subject of her Majesty. The spirit of freedom and tolerance, of which Englishmen are prone to boast upon every available occasion, has made it possible that a naturalized alien should occupy the high position of Chief Magistrate of the greatest city in the world. Unfortunately, however, there is just now rife a feeling of resentment against anything foreign among the masses, which Mr. Polydore de Keyser will, we hope, do nothing to aggravate. he has hitherto demeaned himself under inquisitiveness of a peculiarly active kind so wisely and so well that we may safely give him credit for sufficient tacticianly discretion to sail the civic ship safely and unimpaired through the troubled waters into which, we fear, she is destined to pass before the expiry of his term of office at the helm.”

A rather amazing article which seems to be saying that although we are tolerant, just keep quiet and see out your term as quickly as possible.

As a Catholic immigrant from Belgium, Polydire de Keyser who started selling Maitrank through newspapers was now the owner of the Royal Hotel, Blackfriars and the Lord Mayor of the City of London – quite an achievement.

The following portrait of de Keyser (© National Portrait Gallery, London) shows him in November 1887 at the start of his year as Lord Mayor.

And a photo of him during his term as Lord Mayor:

During his term of office, de Keyser took part in all the activities expected of a Mayor. There were preparations for an exhibition in Paris, he attended fund raising events (for example a “Smoking Concert” in aid of Police Charities), there was plenty of entertaining at the Mansion House, concerts at the Guildhall School of Music, fairs and bazaars to be opened.

In May, probably due to his heritage, there was a reception and dance at the Mansion House for the “burgomasters and aldermen from Belgium” at which there were “over 500 ladies and gentlemen present to meet the representatives of Belgian municipalities, and the guests on arriving were received in the saloon by the Lord Mayor and the Lady Mayoress” – one of the very few references to de Keysers wife, Louise Piéron who he had married in 1862.

During his term of office, there were continuing critical, often abusive, articles written about de Keyser, for example:

“The worthy Polydore de Keyser must be either an exceptionally guileless or an abnormally conceited person. Last week he inspected the boys of the training ship Warspite, and, of course, favoured them with the usual florid oration. In the course of his speech he announced that the Lady Mayoress had great pleasure in giving each boy a Jubilee shilling, which he hoped they would keep throughout their future lives as a souvenir of the present occasion!’ The notion of a British tar treasuring up Herr de Keyser’s shilling for years, and studiously refraining from spending it on grog is really sublime.”

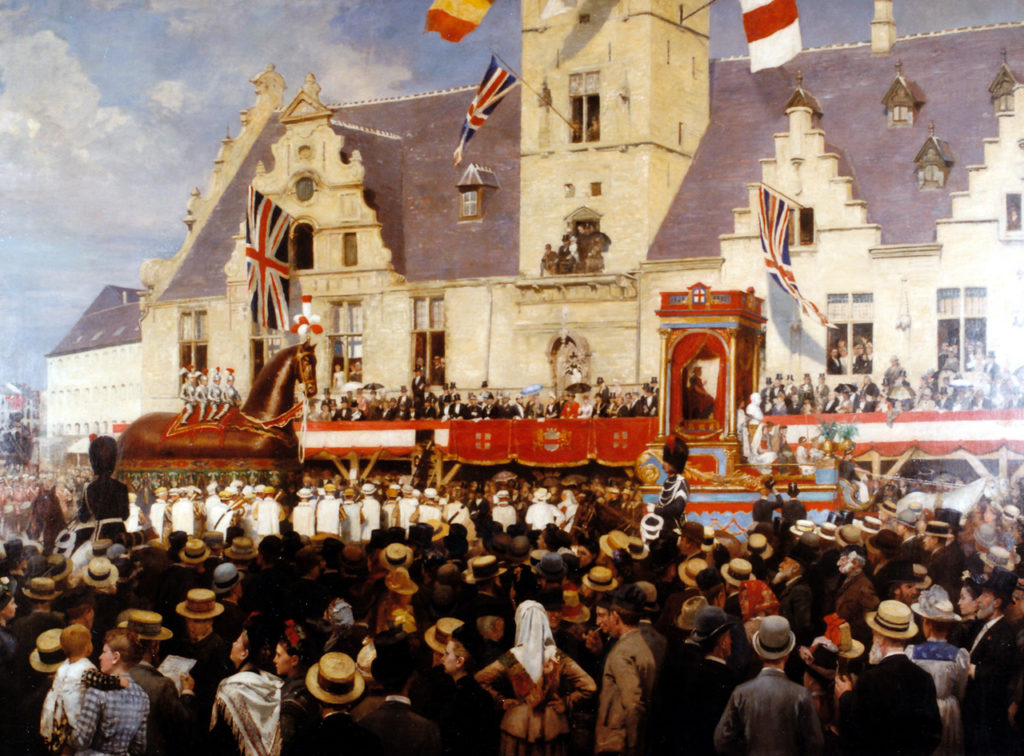

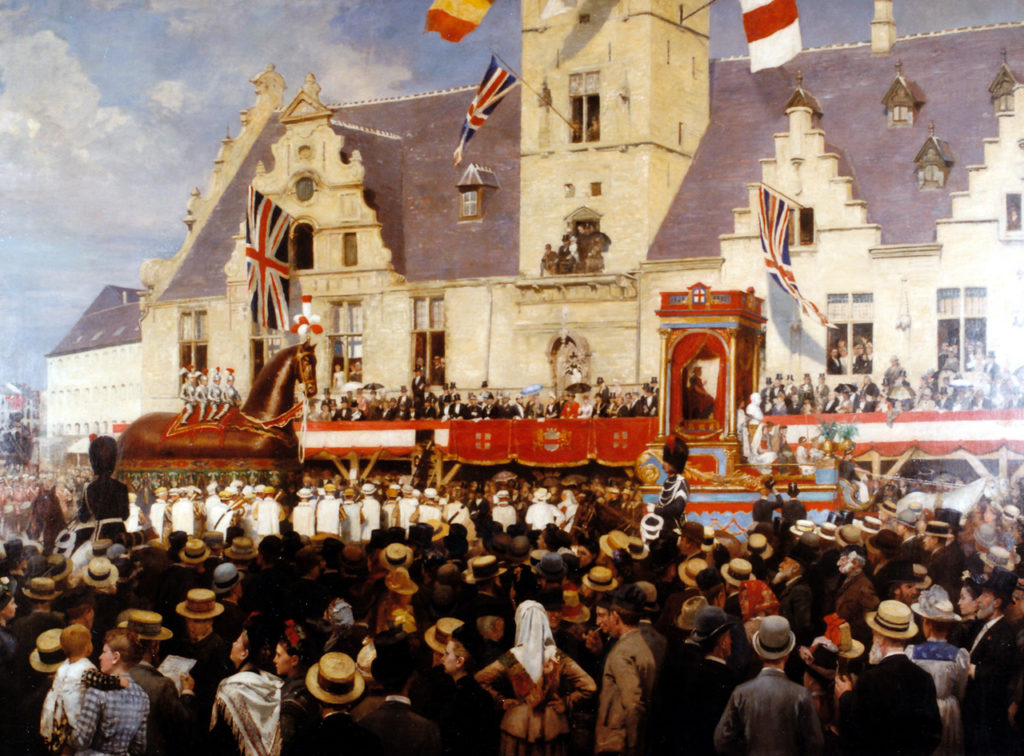

In August, de Keyser returned to the town of his birth, Termonde in Belgium where the “streets and houses were gaily decorated with the mingled colours of Belgium and England, and the arms of the City of London”.

The following painting (By Jan Verhas (kunstschilder) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons) shows the celebrations put on by Termonde for de Keyser’s return:

In September, there was the prospect of a new Lord Mayor with thoughts turning to who would follow de Keyser. Newspaper reports continued to focus on de Keyser’s foreign birth as in the following from the London Letter section of the South Wales Daily News:

“Next Saturday the Livery of the City of London will meet to elect a successor to Alderman Polydore de Keyser as Lord Mayor. After this strange foreign name it will be a relief to get a thoroughly English patronymic as Whitehead. There is little doubt but that Mr Whitehead, who is the senior Alderman not having passed the chair, will be selected.”

The “Jack the Ripper” murders took place during de Keyser’s time as Lord Mayor. Although Whitechapel was outside of his jurisdiction, on the 2nd October 1888 it was reported that “the Lord Mayor, Mr Polydore de Keyser, after consulting Sir James Fraser, Chief Commissioner of the Police of the City of London, announced that a reward of £500 would be given by the Corporation for the detection of the miscreant.”

At the end of his term as Lord Mayor, de keyser became Sir Polydore de Keyser and performed his last public duty as Lord Mayor, the opening of the new Fish Market which is where I found the plaque featured at the start of this post. The London Evening Standard report of the official opening published on the 8th November 1888 reads:

“THE NEW FISH MARKET – The Lord Mayor (Sir Polydore de Keyser) yesterday opened the new Fish Market in Farringdon Street which has been specially erected for the trade by the Corporation of the City of London. The building, which was designed by the late Sir Horace Jones, has been constructed by Mr. Mark Gentry, at a cost of about £26,000. It is situated at the southern roadway leading from Farringdon Road to Long Lane and fronting Snow Hill. The market, which covers an area of 14,000 square feet, has been erected over the joint lines of the Metropolitan and London, Chatham and Dover Railways.

The Lord Mayor, who went in semi-state, accompanied by the Sheriffs (Mr. Alderman Gray and Mr Newton) was received at the principal entrance of the building by the Chairman (Mr. James Perkins) members of the market committee and the Town Clerk.

A silver gilt key was handed by Mr. Perkins to the Lord Mayor, with which he unlocked the huge iron gates amidst the cheers of those assembled outside.

His Lordship having been conducted by the Town Clerk and the members of the Market Committee to a dais, covered with scarlet cloth, at the southern end of the building.

Mr. Perkins, Chairman of the Markets Committee, briefly explained the circumstances which had induced the Corporation to construct the present market. The old fish market on the other side of the roadway, which was originally intended for the sale of fruit and vegetables, had proved a loss to the Corporation of about £10,000 a year. Hence the erection of the present market, Billingsgate having proved insufficient for the supply of fish for the Metropolis. Nearly every shop in the new market was let, and the old market would be used in future for fruit and vegetable. the Corporation hoped that it would be successful, and prove advantageous to the salesman.

The Lord mayor, who was heartily cheered, in declaring the market open, said he was exceedingly pleased to think that his last public duty in his official capacity was to open a market which, he hoped, would result in great benefit to the community, to the Corporation, and to the ward of which he was Alderman (cheers). the Corporation had for years past shown the great interest it took in these matters, and how thoroughly alive it was to the great responsibility of making all our markets as complete and as commodious as possible (cheers). In addition to supplying the wants of London and the suburbs, which now numbered nearly 6,000,000 inhabitants, our markets supplied the wants of the people all over the country. Having complimented the architect and builder upon the magnificent market which they had succeeded in producing, his Lordship formally declared the market open,

Cheers having been given for the success of the market, the proceedings terminated.”

de Keyser ended his term as Lord Mayor at the end of the same week as opening the new market. Even then, newspapers continued to provide a negative portrait of de Keyser as a foreigner, for example, in reporting on the banquet for the new mayor, the Pall Mall Gazette on the 10th November 1888 reported:

“The faces of the distinguished guests afford a remarkable study in physiognomy. The new Lord Mayor has a handsome, clear-cut head and an expansive brow, offering a marked contrast to the florid and jolly hotel-keeping countenance of the late Belgian de Keyser. It was very amusing to hear the toastmaster pray for silence of the late Lord Mayor, as if poor Sir Polydore de keyser were dead and about to rise – say, from the Guildhall vaults.”

On the 4th December 1888, de Keyser was at Windsor Castle to receive his knighthood from Queen Victoria.

After ending his term as Lord Mayor, de Keyser continued organising British participation in overseas exhibitions. In 1889 he was the Executive President of the British Section at the Paris Exhibition.

He also continued his role as Alderman of the Ward of Farringdon Without and in October 1891 was presiding over a meeting of the inhabitants of the ward who were objecting to the letting of any portion of land on the Thames Embankment to the Salvation Army as it would be detrimental to the interests of the City including the concern that “there was no doubt that the processions &c, with drums, trumpets and cymbals, would lead to danger”.

In 1892 de Keyser resigned from the post of Alderman on the account of “bodily infirmity” – among other issues, he was going deaf.

In July 1893 a bust of Sir Polydore de Keyser was unveiled at the Mansion House. It was presented as a token of respect to de Keyser who had played an important part in the affairs of the City and the Ward of Farringdon Without.

Sir Polydore de Keyser died on Friday 14th January 1898 after a “long battle with cancer”. His funeral was on the 19th January and on the 20th the London Evening Standard reported on the funeral:

“The remains of Sir Polydore de Keyser, formerly Lord Mayor of London, who died on Friday last, were interred yesterday in the family vault in Nunhead Cemetery. There was a large attendance of mourners, headed by Mr. Polydore W. de Keyser, his adopted son and nephew, and Messrs. C.M. and A. Fevez, other nephews. Among those present were Alderman Sir Joseph Savory M.P. who served as Sheriff with Sir Polydore in 1883; Mr Alderman Treloar, who succeeded him in the Court of Alderman; Mr. W.J. Soulsby, representing the Lord Mayor; Mr. Marshall Pontifex, Ward Clerk of Farringdon; the Rev. Henry Blunt, rector of St. Andrew’s Holborn, who was Sir Polydore’s Chaplain when Lord Mayor; Colonel Sewell, representing the Spectacle makers’ Company; Mr. H. deGrelle Rogier, the Belgian Consul; Mr. Wilhelm Ganz, Mr. E.A. Gruning, Mr. Walter Wood, Mr. C. Val Hunter and deputations from the Belgian and other Societies with which Sir Polydore was associated. The Service at the grave was read by the Rev. John Stevens, rector of the Roman Catholic Church of Our Immaculate Lady of Victories, in Clapham Park Road. Lady de Keyser who died in 1895, is buried in the same vault.”

de Keyser did not have any children of his own, but appears to have had a large extended family, including a number of nephews, one of which he appears to have adopted in some way. In the year before his death, his ownership of the hotel was transferred into a separate company, the Company of de Keysers Royal Hotel Limited. I assume he did this to make the distribution of his assets after his death easier as shares in the company were set aside to provide annuities to various members of his family. His adopted nephew Polydore Weichand de Keyser also inherited an annuity and the residue of his estate.

Sir Polydore de Keyser then fades into history. His nephew however continues to play a part both in the governance of the City and in London’s hotel business.

An article in The Sphere on the 9th May 1908 reports on the opening of a new hotel – The Piccadilly Hotel – of which the nephew Polydore de Keyser (he appears to have dropped the name Weichand) was the joint manager. He was described:

“as a man of great energy and ability. He is the nephew and adopted son of Sir Polydore de Keyser, who was Lord Mayor of London twenty years ago. Educated at Westminster School and on the Continent, de Keyser has devoted many years to the practical study of modern hotel-keeping. The great success of de Keyser’s hotel affords conclusive proof of his administrative ability. he is deputy lieutenant of the City of London and a member of several City companies.”

So as well as the hotel business, he was also following in his uncle’s footsteps in the City of London.

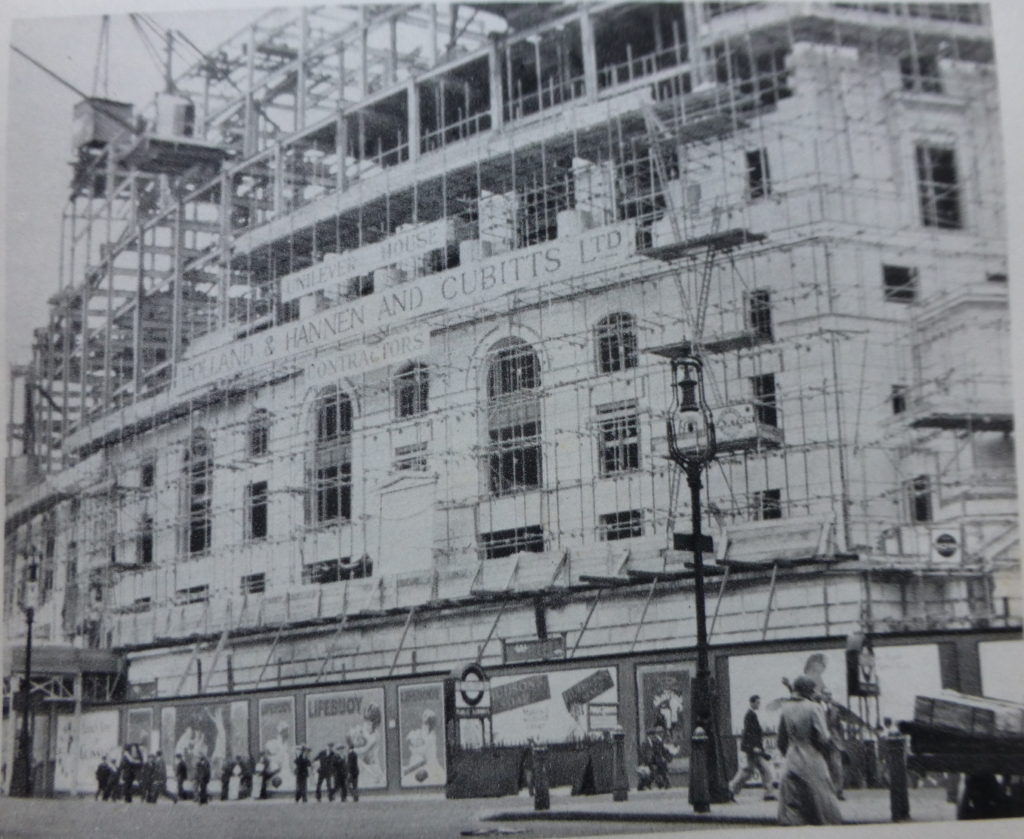

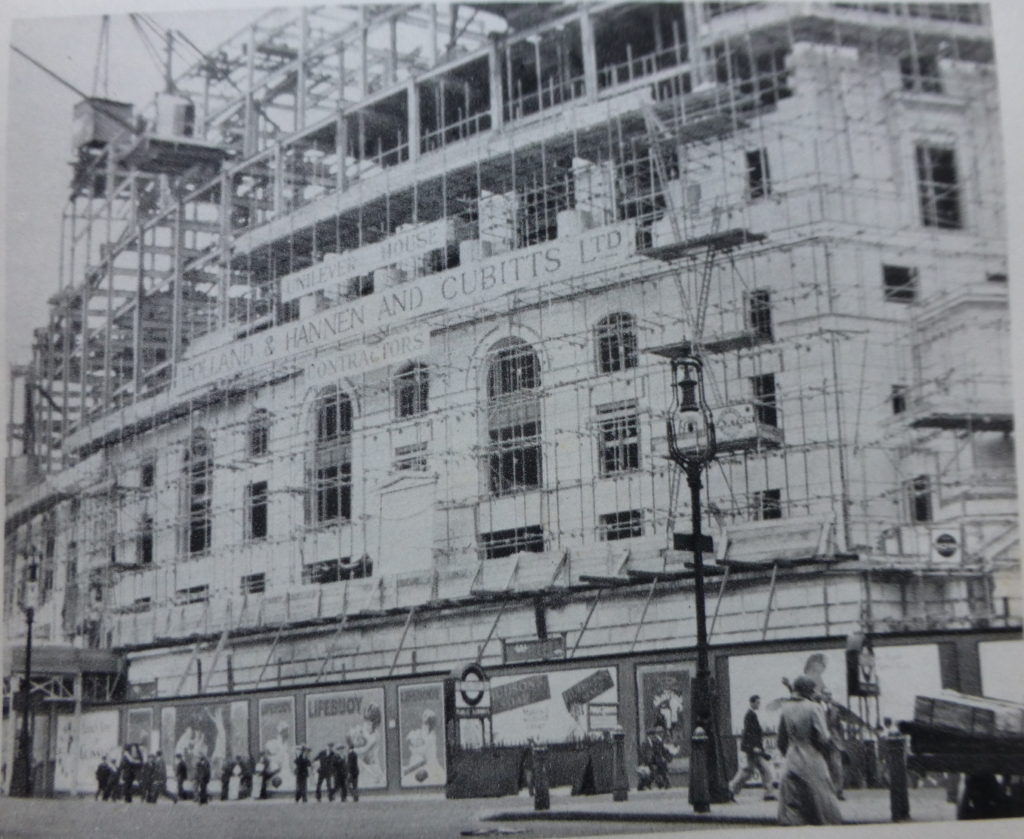

de Keysers Royal Hotel continued in operation until the First World War when it was requisitioned to house officers. I suspect that after the war it had lost much of its pre-war grandeur and the world was a very different place approaching the 1920s than it had been when the hotel was built in 1874. In 1921 it was leased to Lever Brothers who eventually purchased the building in 1930 in order to demolish it, and build their new office, which is still on the site today, and occupied by Unilever (formed by the merger of Lever Brothers and Margarine Unie in 1929).

Margerine Unie originated in the Netherlands in the 1890s when Jurgens Van den Bergh opened the first factory to produce margarine. Given de Keyser’s continental European origins it is somewhat fitting that a part Dutch business occupies the same site as his hotel.

One final question – why did de Keyser feature so prominently in the Supreme Court judgement on Brexit? The Guardian article explains this better than I can, however in summary it appears that the de Keyser hotel company applied for compensation after the hotel at Blackfriars was requisitioned during the First World War. Government did not approve any compensation although Parliament had already set out terms for wartime compensation so it was whether the Government has the right to ignore a decision already made by Parliament, and de Keyser’s judgement of 1920 was one of the landmark cases as the de Keyser Hotel Company successfully sued for compensation.

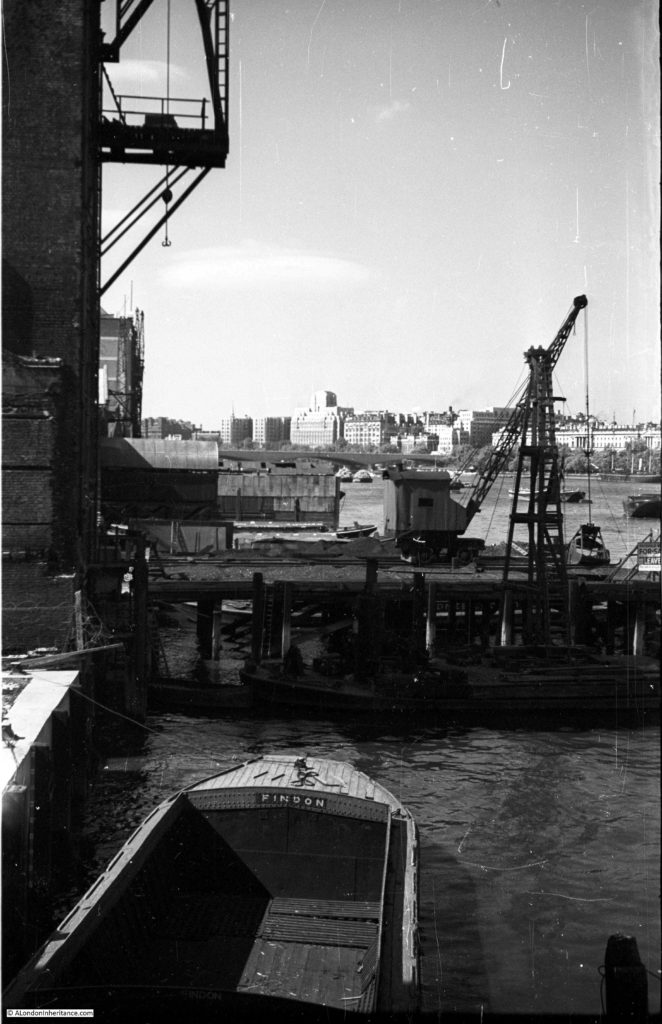

Unilever House is now on the site of de Keysers Royal Hotel at the northern end of Blackfriars Bridge. This is Unilever House under construction:

And this is Unilever House today. The curved facade follows the same curve as de Keyser’s Royal Hotel.

That is Polydore de Keyser, a fascinating Londoner. An immigrant from Belgium who became Lord Mayor of London and a leading London hotelier. As far as I have been able to check, there have not been any other Lord Mayor’s who came to London as an immigrant since de Keyser.

Newspapers only provide a glimpse of his life, but I suspect he must have been highly ambitious and driven to achieve what he did. I hope the plaque at Smithfield survives to keep his name associated with the market he opened in 1888.

alondoninheritance.com