Imagine you are a young Londoner in the late 1940s. Apart from a very brief period being evacuated to the countryside, you spent the whole of wartime in London. National Service then gave you experience of the world outside of London. You want to travel and explore but money is still very tight, international travel is still limited, petrol rationing is still in force, what would you do?

For many Londoners the answer was a bike and the Youth Hosteling Association. Membership of the YHA had reached 100,000 during the war and continued to rise for the first few years after the war due to challenges with travelling outside of the UK and the need for a cost-effective method of travel within the UK.

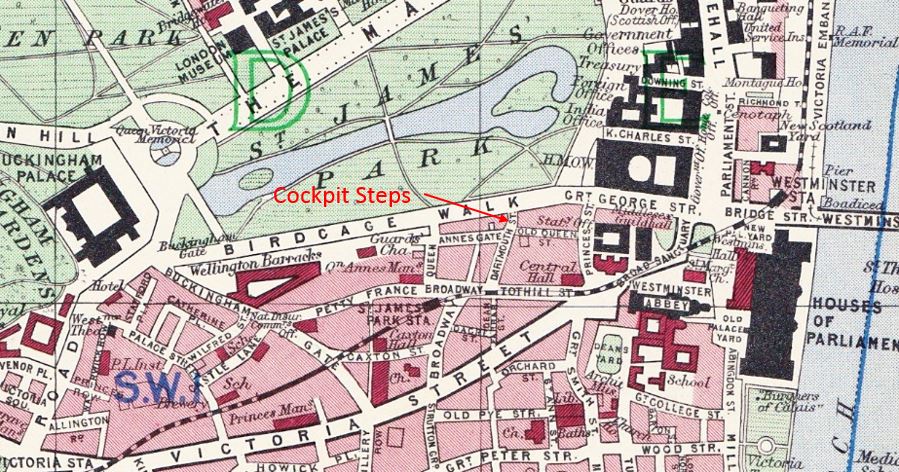

Cycling magazine had published a series of routes centred on London giving directions and distances across the country. The title of this week’s post is the route covering the 160 miles from Marble Arch to Shrewsbury, route number 159.

Main roads just after the war were very different to roads today. This was before the Motorway network, most long distance goods transport was still via train rather than lorry, and petrol rationing (which did not end until May 1950) restricted the amount of private cars on the road.

So for this week, let’s head out from London, along the old A5 and see how the area around Shrewsbury has changed.

Our first stop is just to the south of Shrewsbury and the ruins of part of the old Roman town of Wroxeter (or ‘Viroconium’), which was the fourth largest city in Roman Britain, almost half the size of Roman London. The town was established in around 58AD and lasted for about 500 years during and for sometime after the Roman occupation.

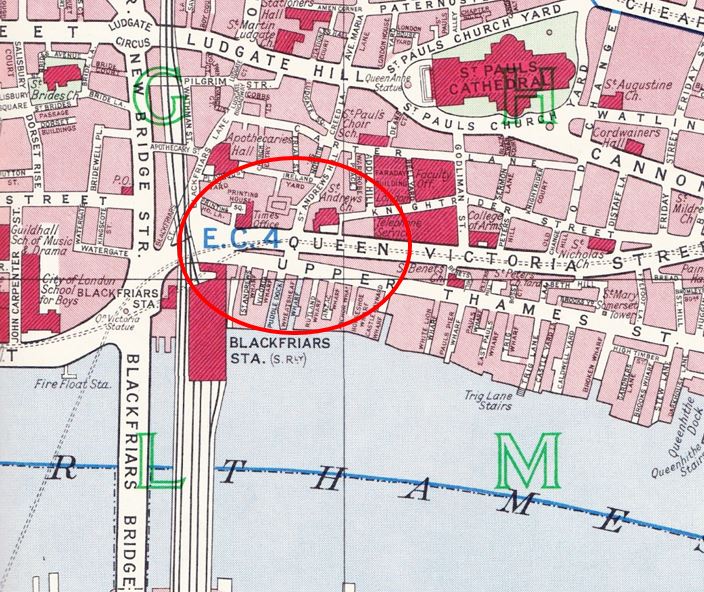

Wroxeter was on Watling Street which started in the channel ports of Dover and Richborough, to London then up-country following a route with parallels to the original A5 (before the current A5 which has been considerably re-routed). Wroxeter also had a quay on the River Severn which gave the town access to the sea.

I would imagine there would have been considerable travel between London and Wroxeter during Roman times.

Much of the town still lies below ground, however the ruins of the Municipal Baths have been excavated and exposed.

This is how they appeared in the late 1940s:

And in 2014 as an English Heritage site. Much the same as you would expect for something that has already lasted for over 1700 years.

Leaving Wroxeter, we continue on the old A5 (now the B4380) and cross the River Severn at Atcham. This is an unusual river crossing as whilst a new, wider bridge was built in 1929 to support increasing levels of traffic, the original bridge built in 1774 was left in place and can still be crossed on foot.

My father took the following photo of the original bridge, with the new bridge in the background in the late 1940s. A summer photo with a slow flowing River Severn and a spot of fishing taking place just into the river.

Again, the scene is virtually the same today as my 2014 photo shows. Apart from some minor changes to the river bank and the sand banks in the river, nothing has changed, however I did not have the luck of finding someone fishing in the river.

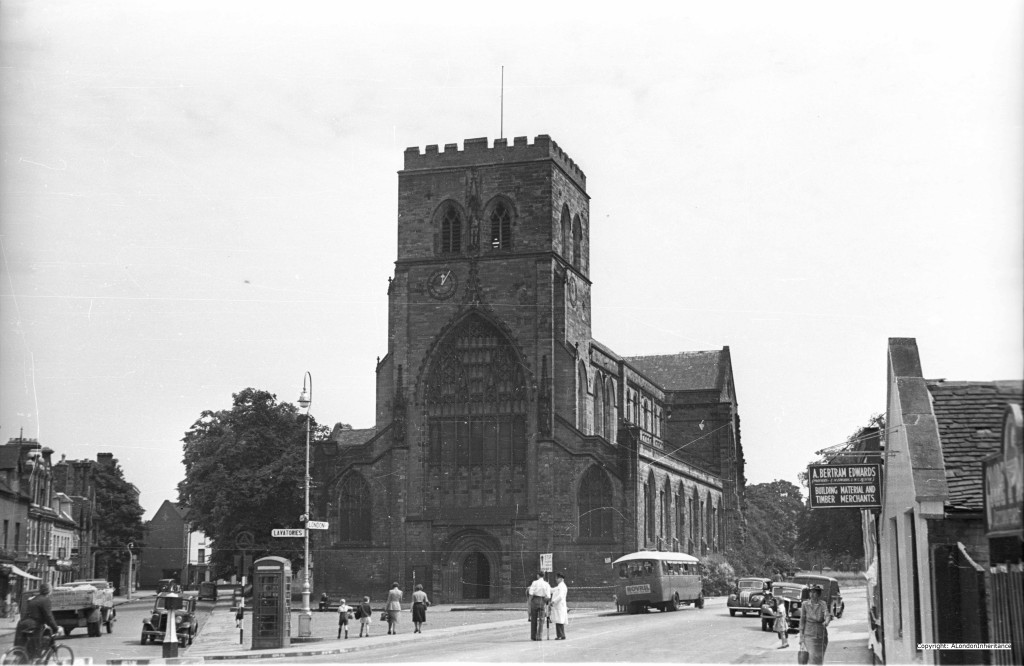

Next we reach Shrewsbury, and one of the first landmarks we pass, just prior to crossing the River Severn to enter the main part of Shrewsbury is Shrewsbury Abbey. The following was the late 1940s view of Shrewsbury Abbey:

And the 2014 view from roughly the same position is below:

A few changes to road layout and street furniture, however very similar to the scene some 65 years ago.

The Abbey is close to the River Severn and unfortunately suffers from flooding relatively frequently. The Abbey was founded in 1083 although today only the nave survives from the original Abbey as it suffered much destruction and damage during the dissolution and the post-reformation period and also during the Civil War as Shrewsbury was a Royalist town.

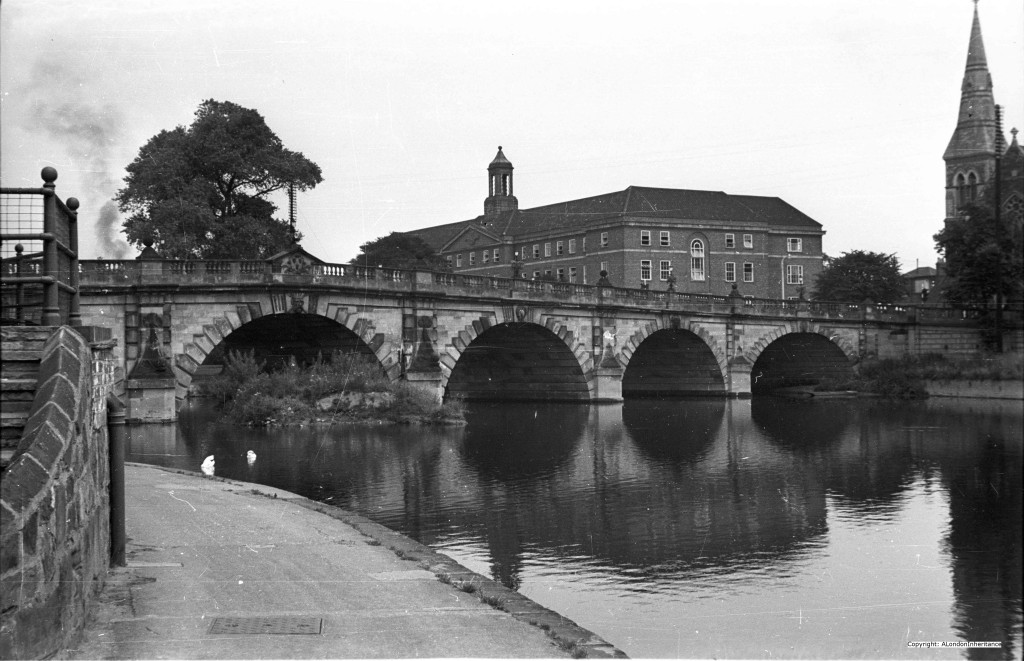

To enter the centre of Shrewsbury we now cross the English Bridge. Again, this was on the original pre-A5 road from London and Thomas Telford used this bridge as part of the route from London to Holyhead for onwards sea travel to Ireland. The bridge is named the English Bridge as it is facing the road route into the heart of England, whilst the bridge on the opposite side of Shrewsbury continuing the road onwards is called the Welsh Bridge as it is facing the onwards route into Wales.

Although the present bridge is a 1926 rebuild of the bridge completed in 1774, a bridge has been on the site for many centuries.

The following is the late 1940s view of the bridge from the side of the River Severn closest to the centre of Shrewsbury:

And the following is my 2014 photo from roughly the same spot. Incredible how, some 65 years later, the view is almost identical.

And now after cycling 160 miles after leaving central London along the original A5 road with light traffic and through some beautiful countryside, we now reach our destination, the centre of Shrewsbury.

Shrewsbury is a very historic market town and county town of Shropshire. The centre of Shrewsbury has many timber-framed buildings from the 14th and 15th centuries and a street plan that is largely unchanged since the medieval period.

This is how one of the main road junctions appeared in the late 1940s:

And again in 2014, apart from minor changes, very few differences in some 65 years.

The timbered building in the centre of the picture is Henry Tudor House, built in the early 1400s and originally a collection of different shops and houses. Henry Tudor (Henry VII) sought refuge here on his way to the battle of Bosworth. This is where the Tudor dynasty replaced the Plantagenet dynasty as Henry’s army killed Richard III.

This is recorded by a sign on the front of the building:

And as proof that many of the original lanes and steps have survived, here is Bear Steps in the late 1940s:

And as they remain in 2014:

Although many of the views are very similar over a period of 65 years, as with London, the way of life would change dramatically. Roads, transport, tourism would not be the same again. The days of long distance cycling for pleasure and to experience countryside and towns would be soon long gone.