City churches are interesting, not just the history of the church, but also for the artifacts that London’s churches seem to accumulate. St Martin Ludgate, or to give the full name St Martin Within Ludgate is a church I have not visited for a while, so on a rather grey day I went for another look inside the church.

St Martin Ludgate is on the northern side of Ludgate Hill. I suspect that the church suffers from the fact that St Paul’s Cathedral is at the top of Ludgate Hill and the cathedral tends to attract the gaze, rather than the historic church along the side of the street.

The view looking down Ludgate Hill with the church and spire of St Martin Ludgate on the right:

St Martin is an old City church, with written evidence dating the church to the 12th century, however Geoffrey of Monmouth writing in the 12th century claims that the church was founded by the Welsh King Cadwallader in the 7th century. Given that this was 500 years before Geoffrey of Monmouth, I doubt very much whether this was based on any truth or factual record.

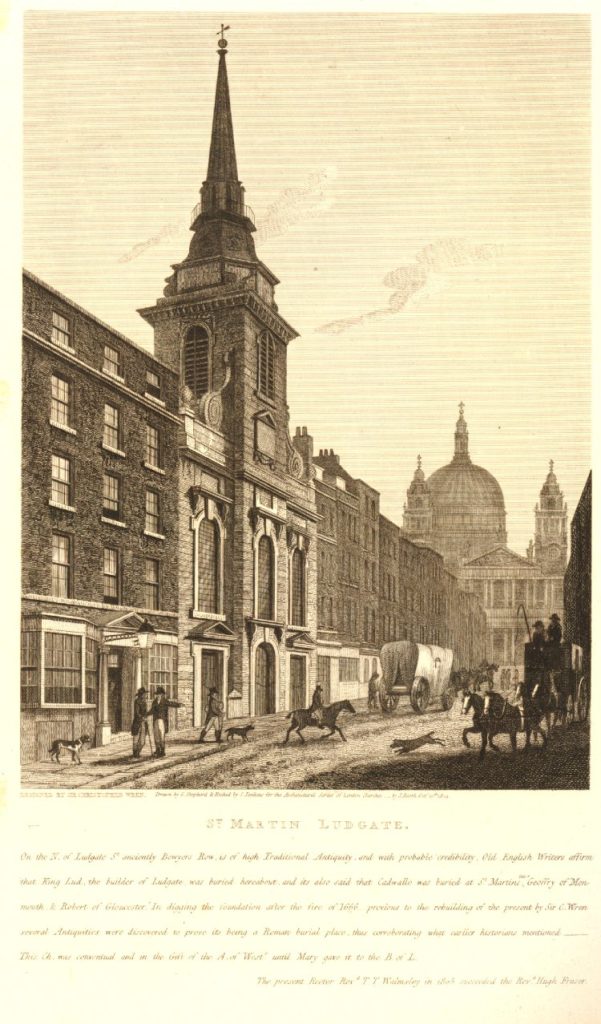

The claim was embellished in the text with the following print from 1814 which shows the tower and steeple of St Martin Ludgate standing clear from the surrounding houses. The author adds that Cadwallo was buried here. The text included evidence that the site was ancient as “several antiquities were discovered to prove it being a Roman burial-place”.

The location was certainly interesting, being adjacent to Lud Gate and the Roman Wall. Travelers from the west would have approached the City along what is now the Strand. Crossing over the River Fleet, then a short distance up the hill to the Lud Gate, with the location of St Martins just inside the wall on the left.

The current church dates from between 1677 and 1686 when it was rebuilt by Wren following the destruction of the previous church in the Great Fire of London, although there is a possibility that rather than Wren, it was Robert Hooke who was responsible for the church.

The original church was slightly clear of the Roman Wall, however the new church was moved slightly to the west and included the Roman Wall in the foundations of the church. Ludgate Hill was also widened at this time, so the new church was also set slightly further back

The spire of the church was designed to be a counterpoint to the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Through the entrance to the church and there is a wide corridor running the width of the building before entering the church proper. This was an attempt to sound proof the church from the noise on Ludgate Hill which must have been one of the busier and noisier streets in the City.

Entering the church and we can see a typical Wren designed City church of the 17th century.

The organ loft above the font:

The font dates from 1673 and was a gift to the rebuilt church from one Thomas Morley.

Behind and to the right of the font is an information panel that confirms that this wall of the church was the original western limit of the Roman City, and below the floor and wall are the foundations of the original Roman Wall, along with remains of the later Medieval Wall.

The full name of the church St Martin within Ludgate indicates that the church was within the City walls.

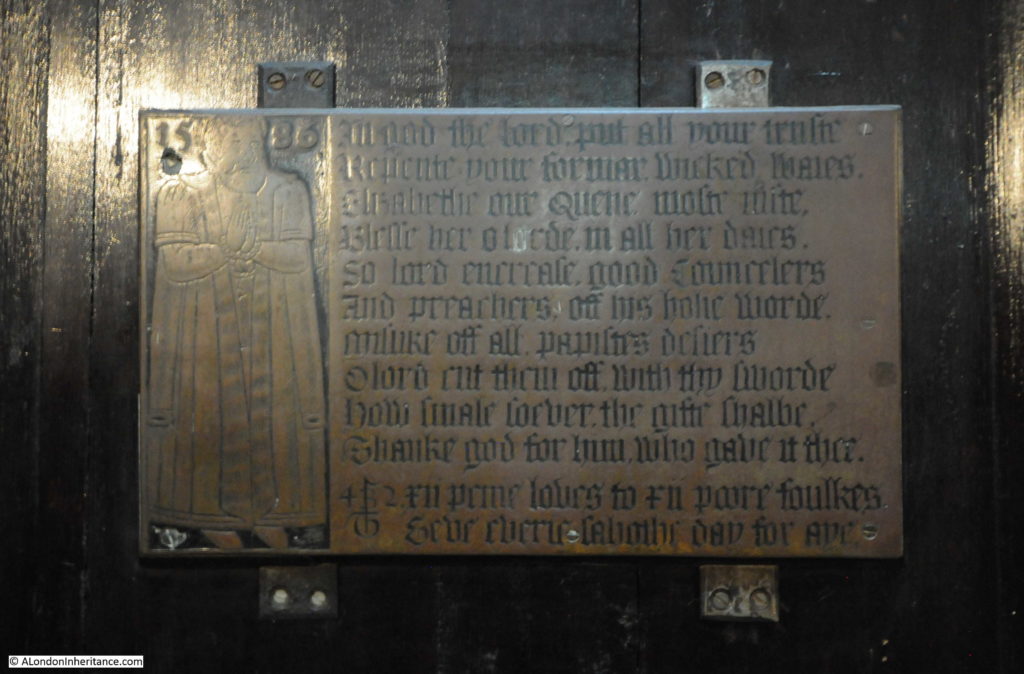

There is an interesting plaque in the church, which holds a hidden message in the text. A brass plaque, now in St Martin’s was originally in St Mary Magdalene’s on Old Fish Street. A serious fire severely damaged much of St Mary in 1886, and as a number of City churches were closing and being demolished under the Union of Benefices Act (an Act to reduce the number of City churches as the population of the City had decreased), the decision was taken not to rebuild St Mary and a number of artifacts were moved to St Martin Ludgate.

The plaque is shown in the following photo and dates from 1586.

The plaque records a charity set up by Elizabethan fish monger Thomas Berry, or Beri. He is seen on the left of the plaque, and to the right are ten lines of text, followed by two lines which describe the charity:

“XII Penie loaves, to XI poor foulkes. Gave every Sabbath Day for aye”

The plaque is dated 1586, and the charity was set up in his will of 1601 which left his property in Edward Street, Southwark to St Mary Magdalen, with the instruction that the rent should be used to fund the loaves. The recipients of the charity were not in London, but were in Walton-on-the-Hill (now a suburb of Liverpool), a village that Berry seems to have had some connection with. The charity included an additional sum of 50s a year to fund a dinner for all the married people and householders of the town of Bootle.

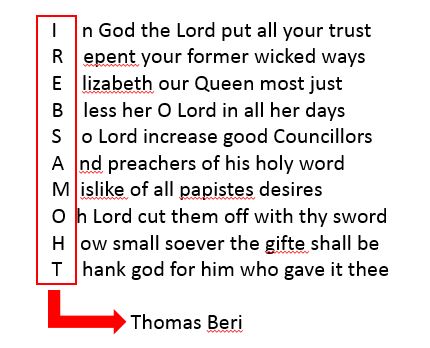

The interesting lines of text are above those which describe the charity. Thomas seems to have spelled his last name either Berry or Beri and these ten lines of anti-papist verse include his concealed name.

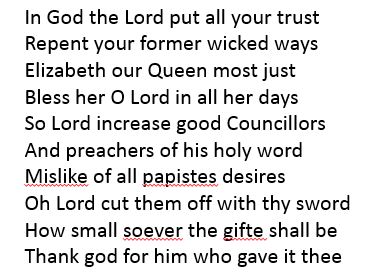

The ten lines are shown below (thankfully “If Stones Could Speak” by F. St Aubyn-Brisbane (1929) have the transcribed text as it was hard to read from the plaque):

If you take the first letter from each sentence and read from the last sentence, you get the name Tomas Beri.

The parish church in Walton-on-the-Hill had a similar brass plaque, however it was badly damaged when the church was destroyed in the Liverpool Blitz in May 1941. The Walton church was rebuilt after the war, and a replica plaque can now be seen.

Unlike the Walton church, St Martin Ludgate suffered the least damage of any City church during the last war, with only a single incendiary bomb damaging the roof.

A closer view of the font. The wall behind the font marks the limit of the original Roman City, and remains of the Roman Wall are below the wall of the church.

City churches tend to accumulate objects, not just from other City churches, but from across the world. For some reason, St Martin Ludgate has a large chandelier from the 18th century which was originally in St Vincent’s Cathedral in the West Indies.

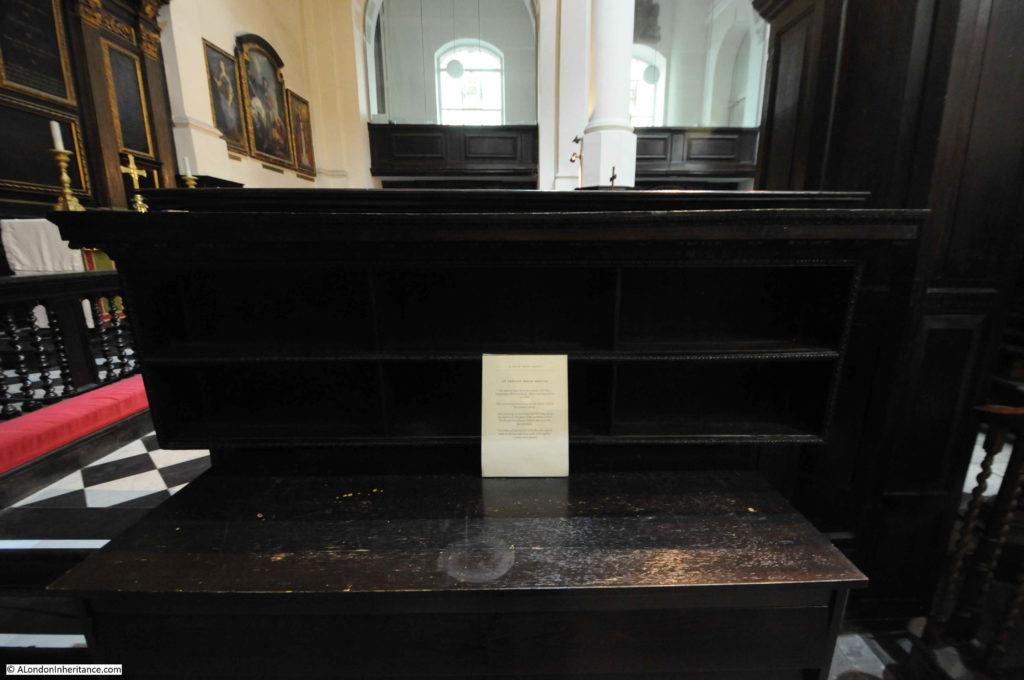

The chandelier is unusual as the majority of objects in the church appear to have come from St Mary Magdalen, including these bread shelves:

On display within the church is one of the bells from the post Great Fire rebuild. The bell dates from 1683 and was a “Gift of William Warne, Scrivener to the Parish of St Martin’s Ludgate”:

In a side room of the church is an interesting 17th century carved pelican:

The symbol of the pelican feeding its young is a very early Christian representation of Jesus. It comes from a pre-Christian legend that in times of famine, a mother pelican would pierce her breast, allowing her young to feed on her blood, thereby avoiding starvation.

Apart from the slender spire, there is nothing remarkable about the building of St Martin Ludgate, and the church is over shadowed by the much larger cathedral a bit further up Ludgate Hill.

The key though with City churches is that despite the ever-changing City, they are stable reference points, providing the same function for over 900 years.

St Martin Ludgate has the added bonus that the west wall of the church marks the western boundary of the original Roman city, and the Roman wall.

And whilst pondering the Roman city, we can also wonder why Thomas Beri decided to conceal his name in the plaque, or what game he was playing with the future back in 1586.