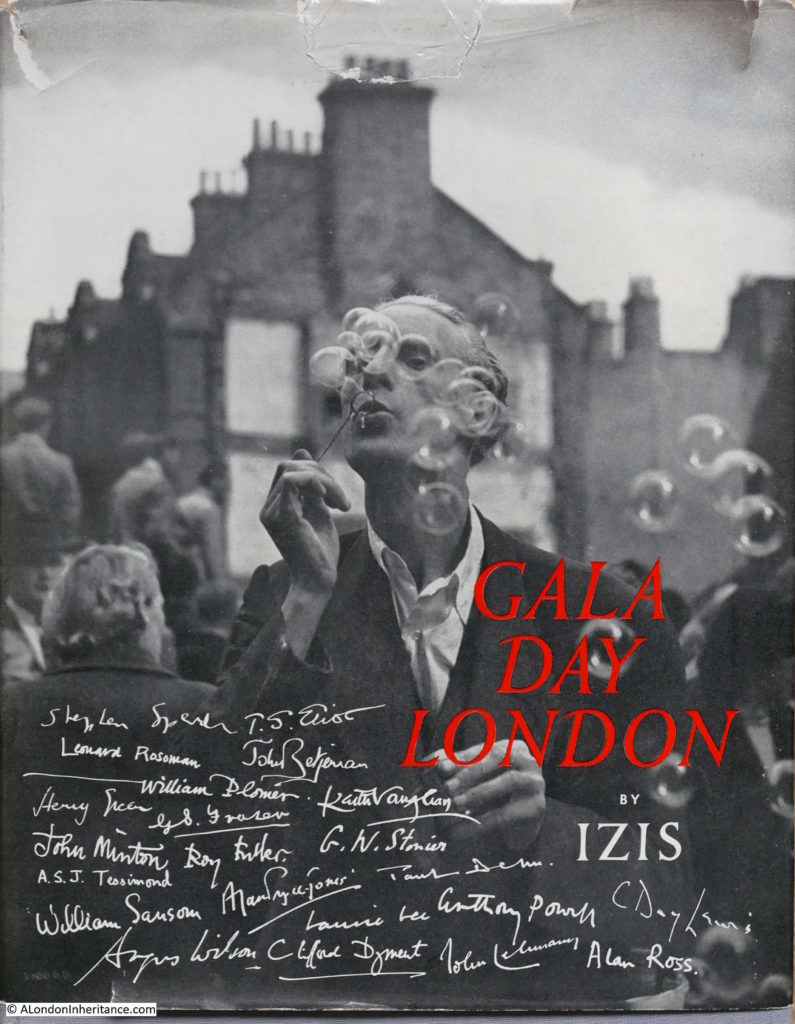

Gala Day London by Izis was published in 1953 and brings together the photography of Izis Bidermanas with the words of writers. artists and poets of the day. The aim of the book was to have:

“Twenty-two amongst the most representative of our writers, poets and artists have contributed original texts relating to the photographs. Together their work forms a unique anthology both of the creative impulse which is alive in Britain today and of how London appears to our generation.”

The book is a wonderful collection of full page black and white photographs of London and Londoners, providing a snapshot of the city in 1953.

Izis Bidermanas was born in Lithuania in 1911, but moved to Paris in 1930 to pursue his interest and career in photography. Being Jewish, he had to leave Paris during the war and escaped to Ambazac in south central France, part of Vichy France. It was here that he changed his first name from Israëlis to Izis to try to disguise his origin, but he was still arrested and tortured by the Nazis. He was freed by the French Resistance, who he then joined and took a series of portraits of resistance fighters which were published after the war to great acclaim.

After the war he returned to Paris to continue his photographic career and also started publishing books which portrayed his subjects in a humanistic, affectionate and nostalgic style.

Izis published a couple of books of London photography in 1953, The Queen’s People and Gala Day London – both full of wonderful photos that capture London at a specific point in time.

So why am I featuring Gala Day London for this week’s post?

It was one of my father’s large collection of London books and I was browsing through the book a few months ago and found one of his photos between two of the pages. Written on the back of the photo was “Newsagent – Emmett Street / Westferry Road, 5th September 1986”.

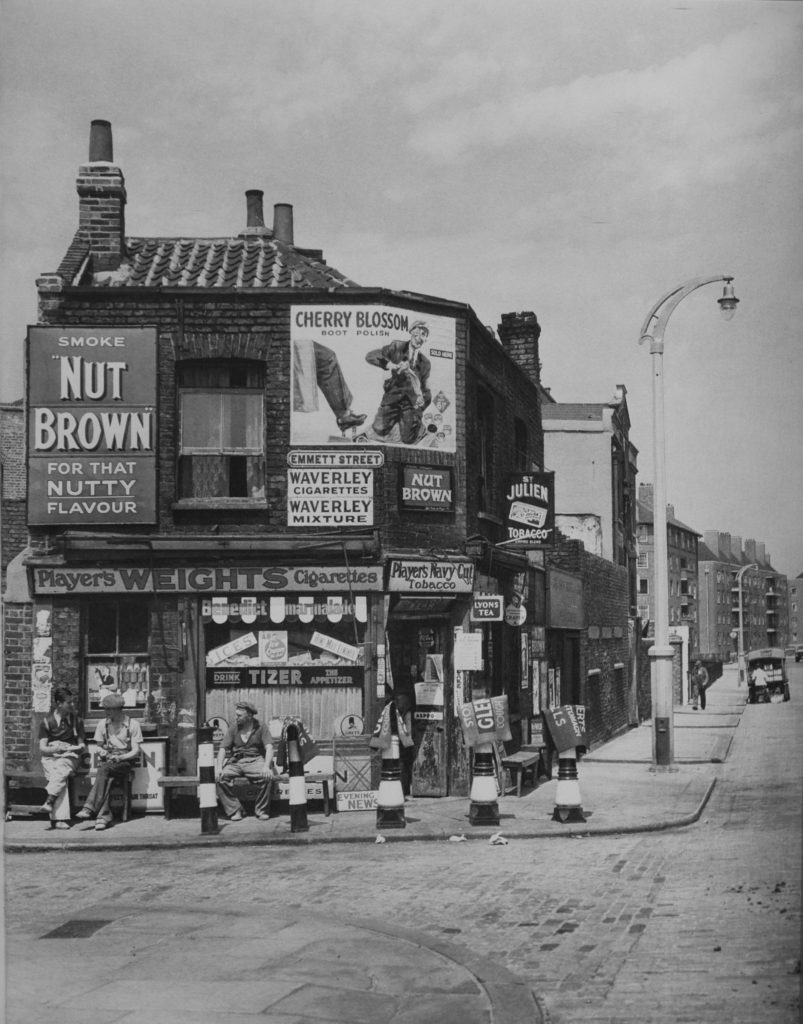

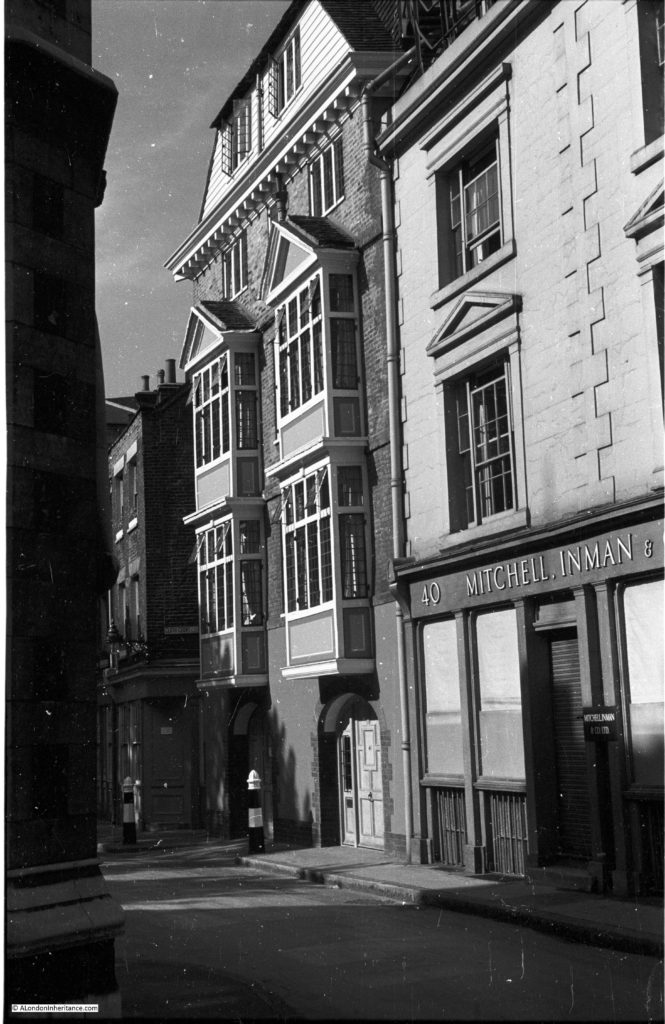

The photo was inserted alongside the page that had the following Izis photo:

And this is the photo I found inserted in the book, my father’s photo taken on the 5th September 1986:

Remarkably the photo is of the same location. Under the white washed walls, the bricked up windows, the loss of all the signage and the bollards on the pavement the building is the same.

The Emmett Street sign appears to be the same, but has been moved lower down the wall and painted over so is not immediately obvious. The larger wall of the building behind can also be seen in both photos.

It is incredibly sad to compare the two photos. What had in 1953 been a typical East London newsagent was now derelict and waiting for demolition as part of the redevelopment of the area around Canary Wharf.

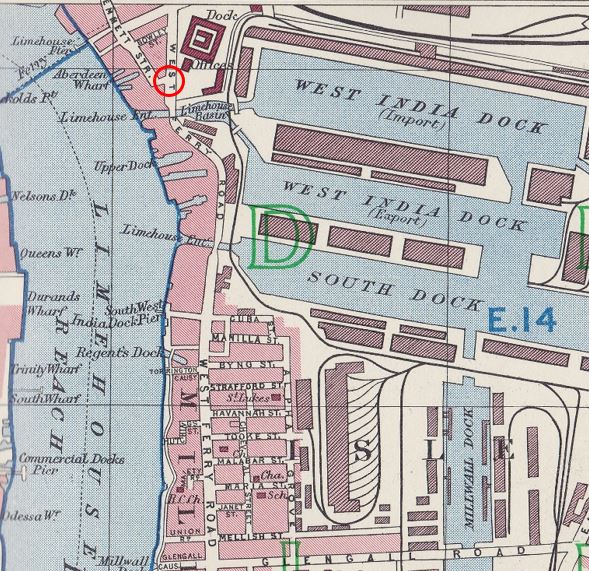

My father’s notes on the back of the photo gave me the location – Emmett Street and Westferry Road so I had to find the location today.

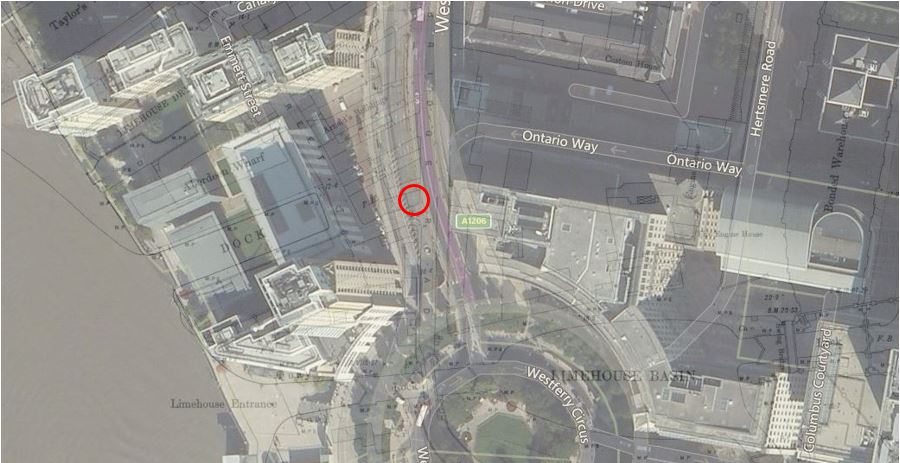

The map below is an extract from the 1940 Bartholomew’s Atlas of Greater London. I have put a red circle around the junction of Emmett Street and Westferry Road where I believe the newsagent was located.

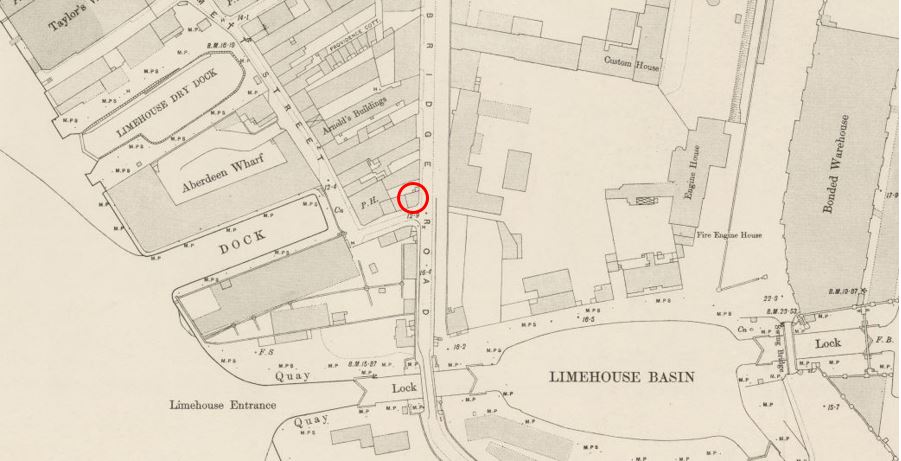

I then checked the 1895 Ordnance Survey map as this is far more detailed and at the same junction there is a building on the corner of the junction with the same angled corner of the building where the entrance was located. I knew the building was on this side of the street as in my father’s photo the pole in front of the wall is casting a shadow, so the wall is facing south.

The Ordnance Survey map is on the wonderful National Library of Scotland web site and the site has the ability to overlay a modern map on the 1895 map with adjustable transparency, so with a modern overlay and transparency the map looks like this:

The link to the NLS site for the map is here.

The map gave me the exact location for the newsagent – underneath Westferry Road where it runs up to Westferry Circus.

A note on Westferry Road. In the 1895 OS map, the road is named as Bridge Road. At the time Westferry Road only ran as far north as the entrance to the South Dock, from there onwards it was named Bridge Road, presumably as this part of the road crossed the entrances to the South Dock and the Limehouse Basin.

By the 1940 map, Bridge Road had been renamed West Ferry Road.

Today, it is still the same name, however in the 1895 and 1940 maps it is West Ferry, today on maps and signs the two words have been combined to Westferry Road.

A couple of weeks ago I had a day off from work and for a change the weather was brilliant so I headed out on the DLR to Canary Wharf and took the short walk to Westferry Circus.

Emmett Street today has been lost beneath all the development of recent decades. Hotels, apartment buildings and one of the entrances to the Limehouse Link Tunnel have all erased this street. Emmett Street developed during the early 19th century to provide a link from Three Colt Street to Bridge Road along the back of the buildings constructed along the river front.

Westferry Circus was partly built over the old Limehouse Basin and the Limehouse entrance from the river. It is an elevated structure built higher than the original level of the land so Westferry Road slopes upward to meet Westferry Circus.

This is the view of Westferry Road as it slopes up to Westferry Circus. I tried to accurately locate the old newsagent building by referencing its position on the National Library of Scotland map, using the buildings alongside, the black lights along the edge of the road which appear visible as black dots on the overlay map, and the position of Ontario Way.

I have marked the location of the newsagent building using red lines in the photo below:

It depends how the land levels have changed with all the building work, but the top of the upper floor of the newsagent would probably have been above the current level of the road.

There are also roads running either side of the elevated approach road to Westferry Circus. This is the view from the side, again I have marked where the old newsagents was located:

This is the view looking up towards Westferry Circus. The newsagent was on the elevated road, to the left of the direction sign. I doubt if the three men sitting outside the newsagent could have imagined that their view would be changing to this over the coming decades – I wonder what they would have thought?

As the weather was so good, here are a couple more photos, this one looking across Westferry Circus:

And this one looking from the edge of Westferry Circus along the Thames to the City. It was here that the Limehouse entrance from the river ran across the open space at the bottom of the steps to a set of locks roughly where I am standing.

It was fascinating to find my father’s photo in among the pages of Gala Day London. It was one of a number he took in the 1980s around the Isle of Dogs and East London.

The layout of the book consists of an Izis photo on the right hand page and a poem or descriptive text on the left. A wide range of authors and poets contributed to the book including John Betjeman, Laurie Lee and T.S. Lewis.

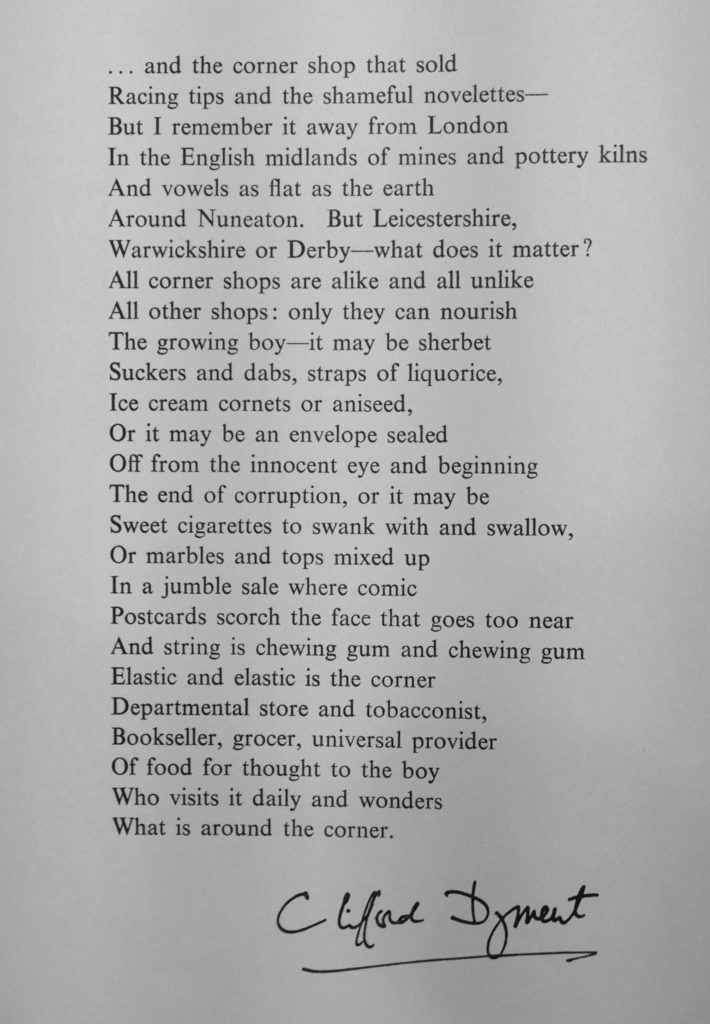

Opposite the Emmett Street photo was a poem written by Clifford Dyment, a poet, literary critic, editor and journalist, who lived from 1914 to 1971. His contribution appropriately is to the wonderful variety of the corner shop:

The lines “it may be sherbet suckers, dabs, straps of liquorice” perfectly describe my memories of corner shops as a boy.

I do not know why Izis singled out this newsagent out of all the newsagents and cornershops there were across London at the time, or if the photo was natural or had been set up. The majority of his work in the two London books look natural. The following from the introduction to Gala Day London provides some clues of how he selected his subjects:

“Izis Bidermanas is both a foreigner and a poet who uses a camera. When we look at his photographs we recognise that the obvious subjects have been avoided and that ‘there is a poetry of cities which has nothing to do with things that receive three stars in the guide books. Perhaps it has been specially by way of Londoners rather than by stone and stucco that he has grown to know London. His pictures are above all an evocation of daily life. He has had a capricious sitter and has not attempted to bend her to his will but has preferred to attend upon her whim. This attitude has probably been responsible for the sense of humanity which arises from the pictures.”

It is always strange to stand at places such as Westferry Circus and look down on the view today knowing what was once here – it was then time to move on and make the most of the weather as I had a few more East London locations to track down and photograph.