Before heading to Campden Hill, a quick reminder that if you are interested in discovering the history of the New River, New River Head, the Oak Room and Devil’s Conduit, there are a few tickets remaining for a walk by Islington Guides starting this coming week. I will be guiding on a couple of these walks and they can be booked at this link.

For this week’s post, I am in the area between Kensington Gardens and Holland Park, in Campden Hill Road, looking up the street towards the now demolished water tower as seen in this photo by my father, and dating from 1951:

The same view in August 2022:

The view nearest the camera has hardly changed. The buildings on either side of Campden Hill Road are the same. What has changed is the view in the distance where the water tower once stood is now a development of flats.

The Campden Hill water tower was built as part of the 19th century roll out of water supplies across an expanding London.

The Grand Junction Water Works Company purchased the land at the top of the road in 1843, and built a reservoir. This was followed by a pumping station and the water tower. (I have also read reports that the water works opened in the 1820s on land purchased from the Dowager Marchioness of Lansdowne, and that the water tower was built in 1847).

The water tower is unusual in that it did not hold a water tank. Instead, large pipes ran up the tower, and these would hold water, with the height of the pipes adding to the pressure of water supplied from the location.

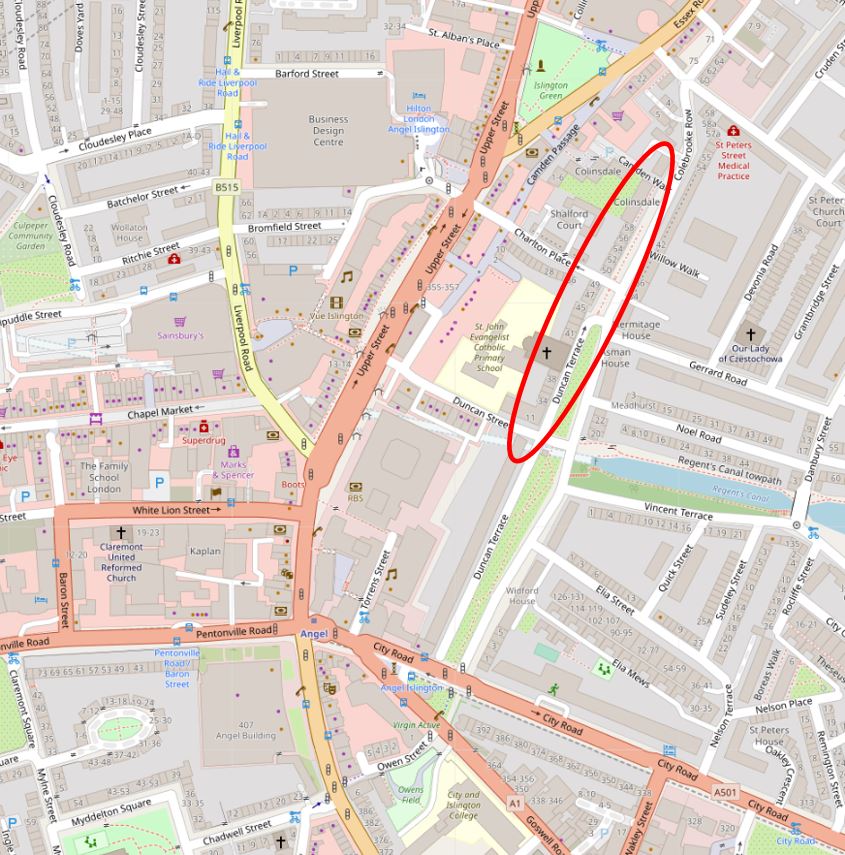

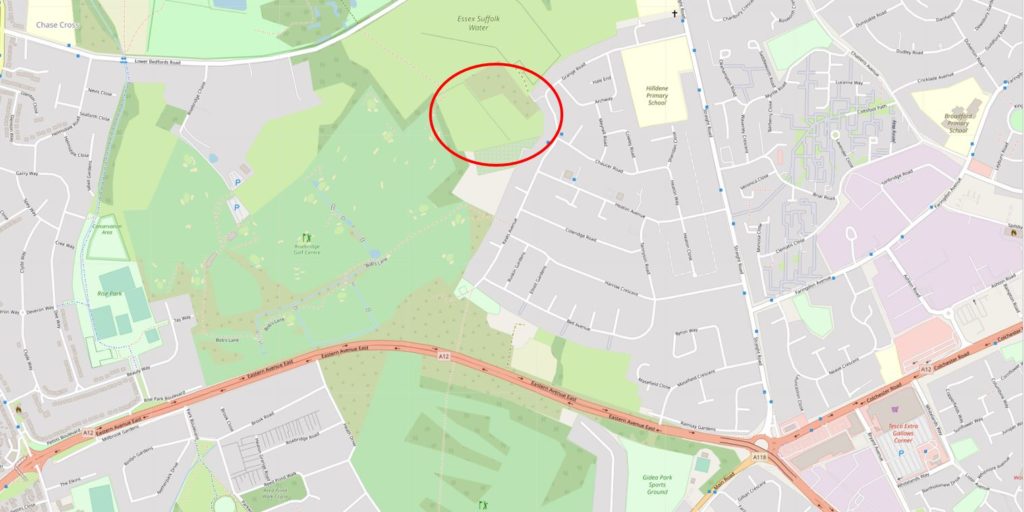

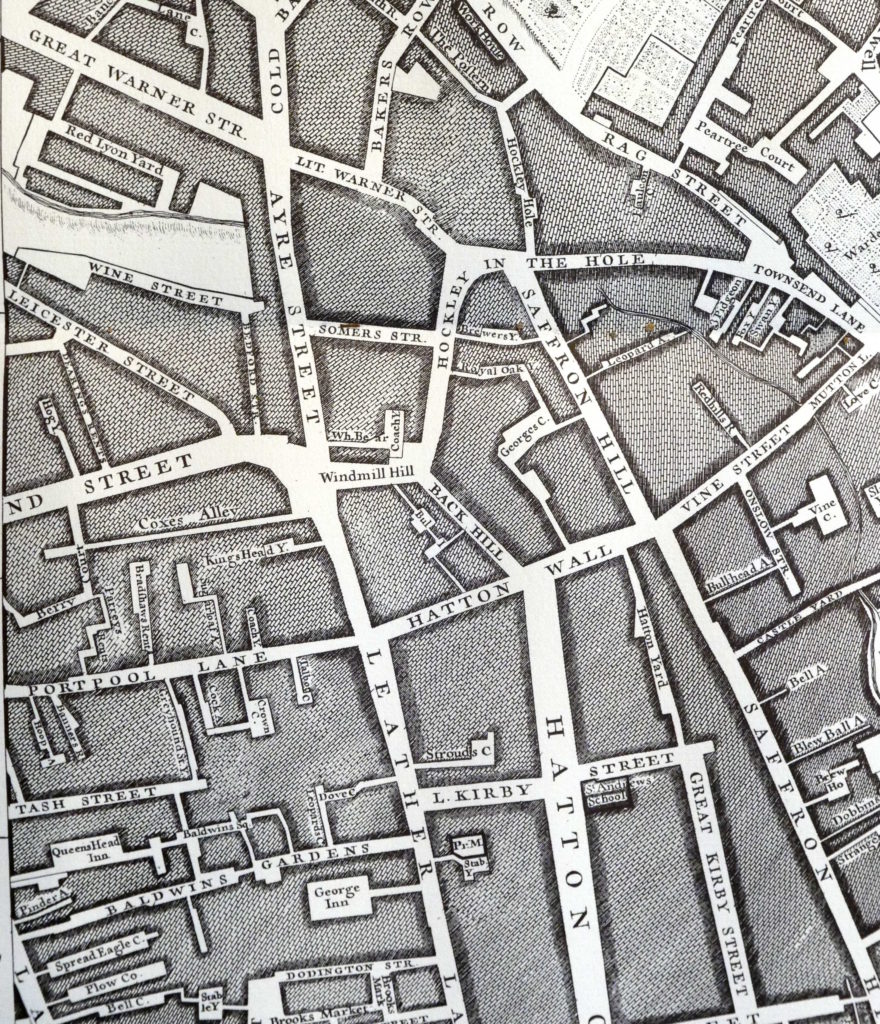

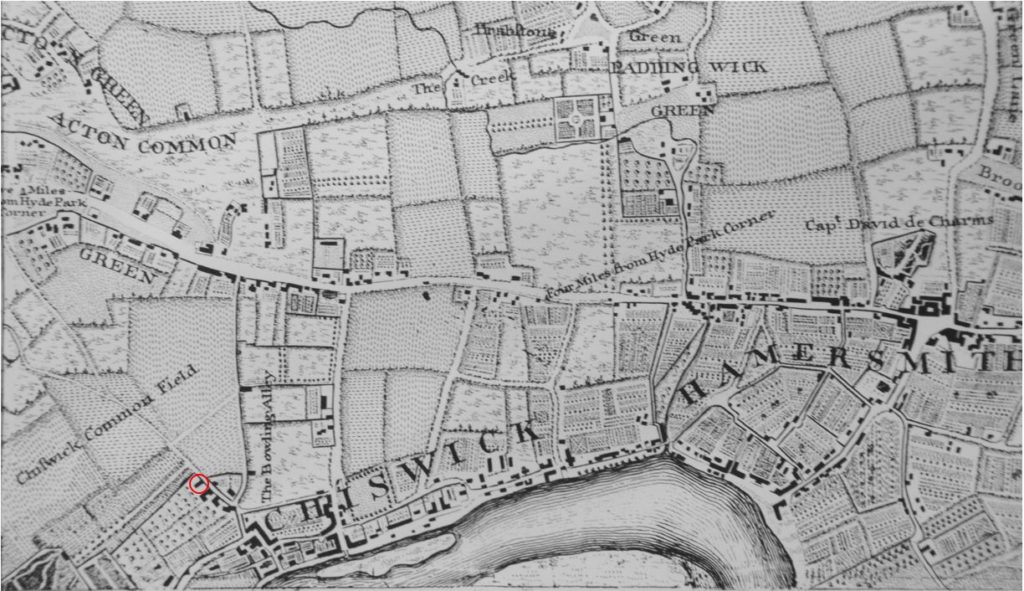

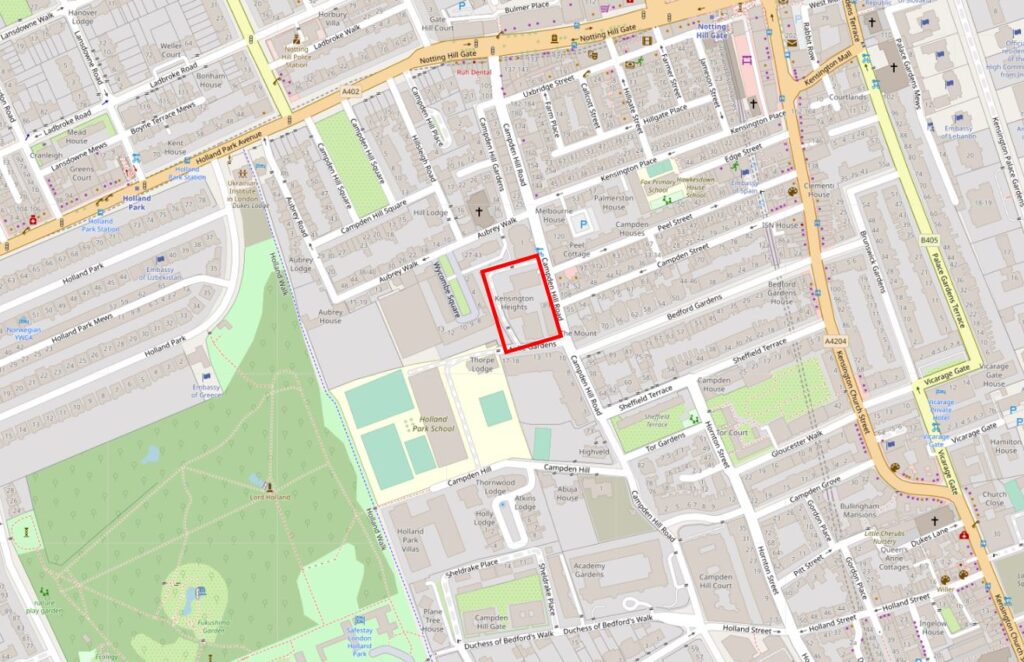

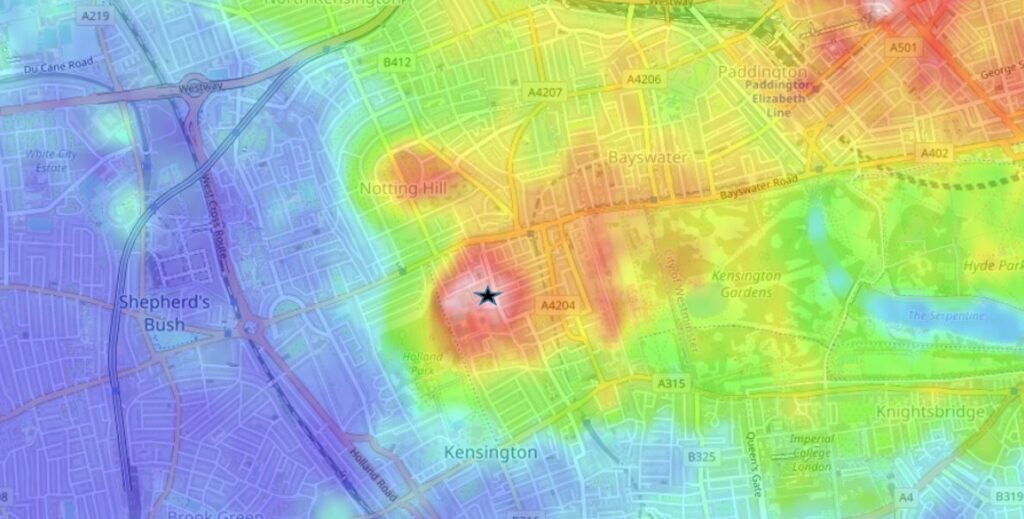

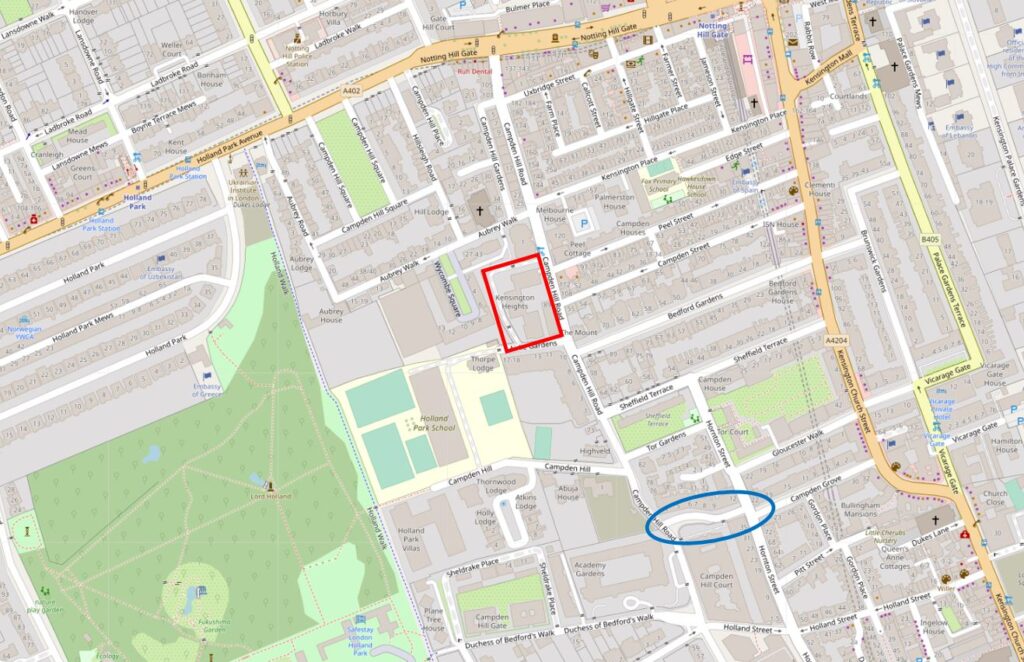

I have shown the location of the water tower, and the associated water supply infrastructure, within the red rectangle in the following map:

The map shows that the water tower was just over half way up Campden Hill Road, but we need to look at another type of map to understand why it was located at this point in Campden Hill Road.

The following map (from the excellent topographic-map.com) shows land height as different colours, with blue as the lowest height, up through green, orange, red and pink as the highest. I have placed a black star symbol at the location of the water tower, and as can be seen by the surrounding colours, this is the highest point in the area, and the natural height of the land would have given a pressure advantage to water from the site, to which the water tower would have added.

The name of the road – Campden Hill Road – also highlights that the road runs both up and down a hill. Next to the original location of the water tower, we can see the road descending in both directions. Looking north:

And looking south:

There was a local myth that involved the height of the land where the water tower was located. Almost opposite the location of the water tower is a pub called the Windsor Castle, and the myth was that before the water tower was built, a keen eyed observer could see the real Windsor Castle from this high point, hence the name of the local pub.

This myth was certainly still going into the 1950s when a letter in the Kensington Post disputed that you could have seen the castle from this point, and it was even doubtful that you could see the castle from the top of the tower.

This source of the name is not mentioned on the pub’s website, which does though claim the 1820s as the age of the pub, so it does pre-date the water tower.

The water tower and associated infrastructure became part of the Metropolitan Water Board in 1904 when the MWB took over the assets of the many water companies operating in London, and brought these under the control of a single, London wide, water supplier.

The water tower was last used for the storage of water within it’s pipe in 1943, and was then redundant for a number of years. Plans to demolish the tower started in the early 1050s and in the 28th of March 1952 edition of the Kensington News and West London Times, there was an article with the headline “Goodbye to the Great Grey Tower”. The newspaper had asked local residents how they felt about the loss of the tower and reported that their general reply was that they would “Miss it dreadfully”.

The tower would though remain for many years, and during the 1960s it was leased to Associated Rediffusion who had equipment to relay television signals mounted on the tower.

There were a number of proposals for what would replace the tower throughout the 1960s, many reported in the Kensington Post, who also sent a photographer to take some photos of the view from the top of the tower.

It would finally be demolished in the first months of 1970, and the site of the water tower and associated works is now occupied by the housing seen in the following photo:

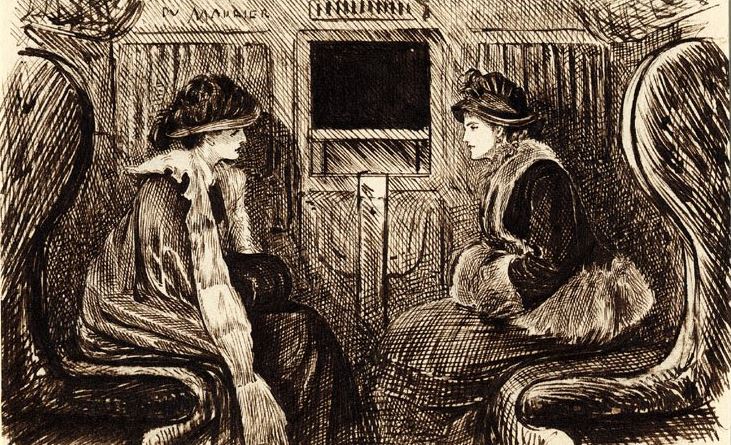

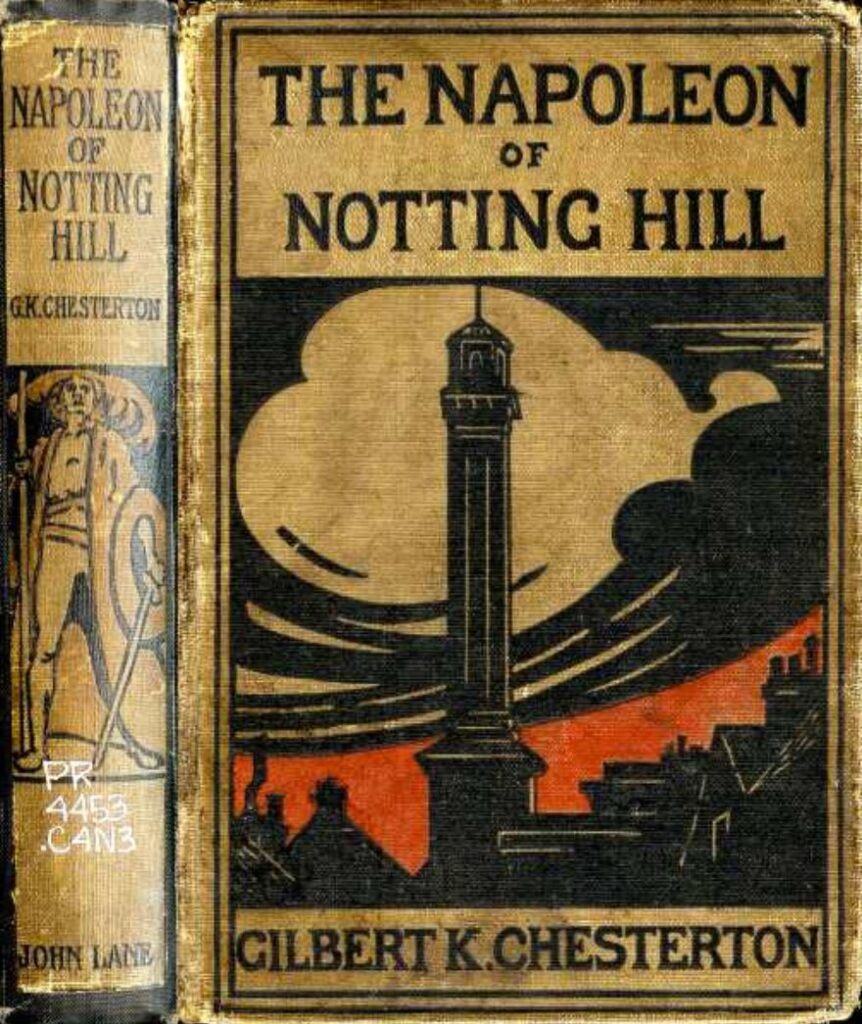

As well as being part of London’s water supply, and a local landmark, the Campden Hill water tower is also unique as it is (as far as I know) the only water tower to feature in, and on the cover of a work of literature:

The Napoleon of Notting Hill by G.K. Chesteron is a rather unusual book. Published in 1904, it tells of the story an alternative reality, where the country is ruled over by a randomly selected head of state, one Auberon Quinn who had been a clerk. Quinn decides to turn London into a form of medieval city. One man, Adam Wayne, takes this very seriously, and uses it as a means to support local pride. Wayne even went to the length of setting up a Notting Hill army to fight invaders from other neighbourhoods – hence the title of the Napoleon of Notting Hill.

Theoretically set in a London of the future, the book describes technology and the city as it was when the book was written.

The water tower features many times in the book, including in Chapter Three —The Great Army of South Kensington, where the various forces of different streets and local areas assemble and where battle takes place, for example:

“Morning winked a little wearily at me over the curt edge of Campden Hill and its houses with their sharp shadows. Under the abrupt black cardboard of the outline, it took some little time to detect colours; but at length I saw a brownish yellow shifting in the obscurity, and I knew that it was the guard of Swindon’s West Kensington army. They are being held as a reserve, and lining the whole ridge above the Bayswater Road. Their camp and their main force is under the great Waterworks Tower on Campden Hill.”

and:

“In the event of your surrendering your arms and dispersing under the superintendence of our forces, these local rights of yours shall be carefully observed. In the event of your not doing so, the Lord High Provost of Notting Hill desires to announce that he has just captured the Waterworks Tower, just above you, on Campden Hill, and that within ten minutes from now, that is, on the reception through me of your refusal, he will open the great reservoir and flood the whole valley where you stand in thirty feet of water. God save King Auberon!”

The reason why Chesterton set his book in the area, and uses the water tower as a key feature must be that he was born in Campden Hill on the 29th of May, 1874, so he knew the area very well, and the water tower would have been a very familiar feature.

The Napoleon of Notting Hill is a really strange book, but good to have the Campden Hill water tower recorded in a work of literature.

Walking south, down the hill from the location of the water tower is this terrace of large residential buildings:

One of which has a blue plaque recording that the photographer Bill Brandt lived here:

I felt rather guilty taking the photo of Bill Brandt’s plaque on a modern digital camera, when I should have been using my father’s old Leica film camera.

Brandt was a master of film photography. Born in Germany in 1904, he moved to London in 1933, and would spend the rest of his life in the city until his death in 1983.

I have no idea when, and for how long he lived in Campden Hill Road, however a number of his photographs were taken inside the building, many of which date around the 1940s, so he was there for some of that decade.

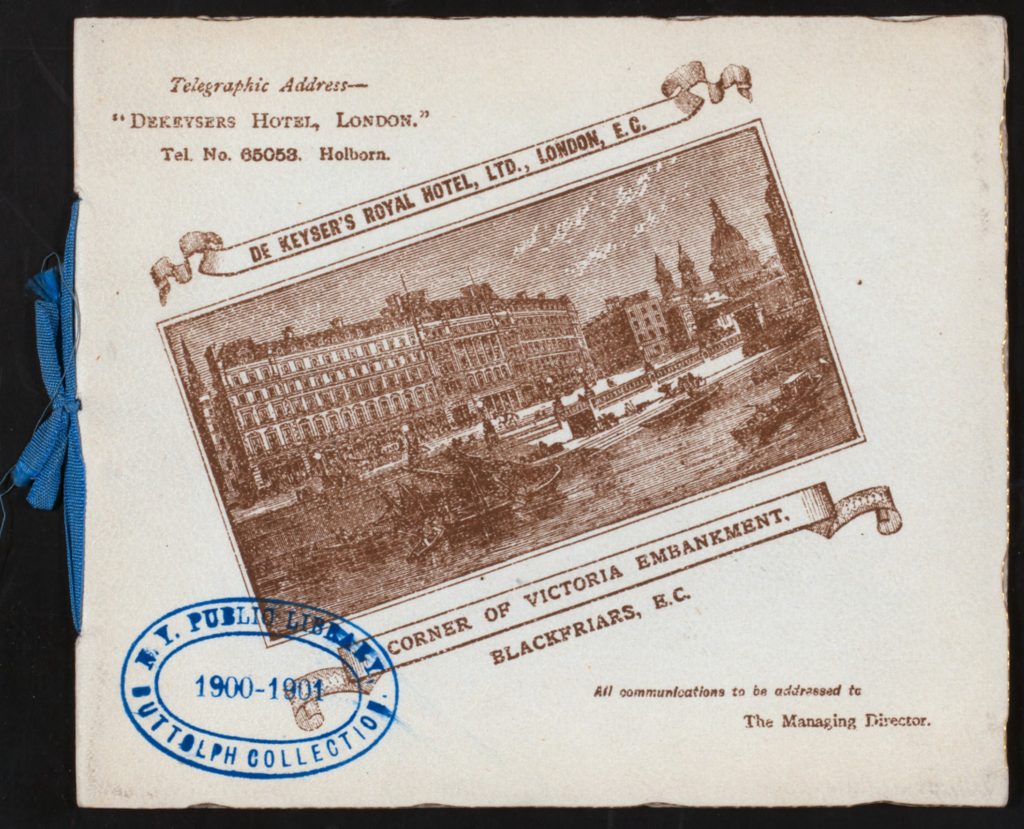

Brandt took a series of photos of London during the war, and his photos of the Underground being used as air raid shelters have become representative of that period in London’s history. Many of his wartime photos of London are in the collection of the Imperial War Museum:

Christ Church, Spitalfields: Man sleeping in a stone sarcophagus in Christ Church:

Continuing on down Campden Hill Road, and the area around the road is full of interesting architecture and plenty of history and interesting characters. I cannot cover everything I would like to in the space of a weekly post, so I will pick one small street which has plenty of interesting stories to tell.

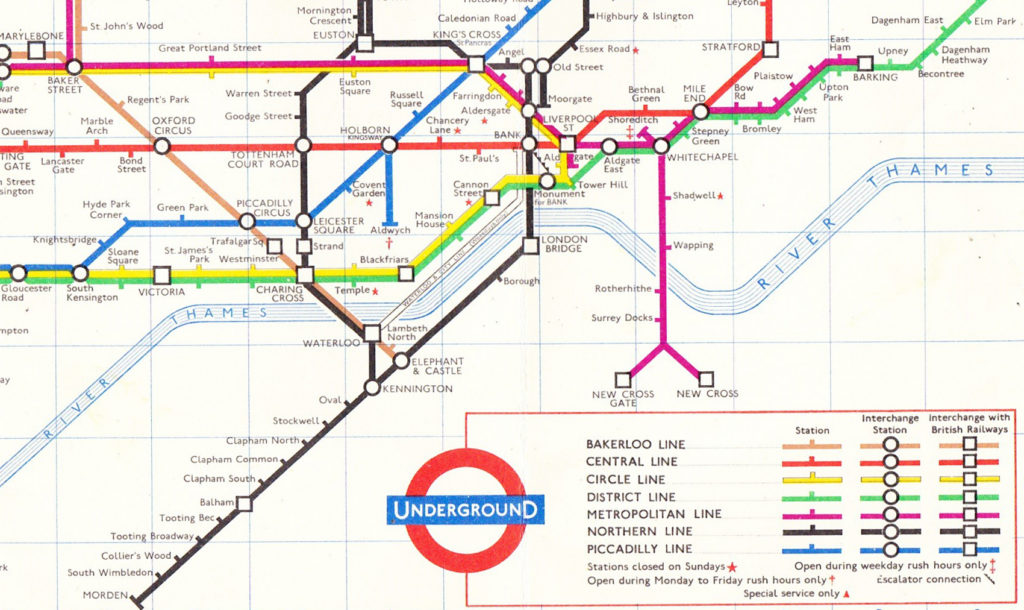

In the map below, I have put a blue oval around Observatory Gardens, a small street that leads from Campden Hill Road to Hornton Street:

I will come on to the origin of the name Observatory Gardens, however lets have a look at the buildings first.

Along the northern side of Observatory Gardens is a continuous terrace of brick houses with white painted detailing.

By 1870, the land now occupied by Observatory Gardens had been purchased by Thomas Cawley, a local south Kensington builder. He subcontracted the construction of the street, however his subcontractors went bankrupt, so Cawley completed the work himself, and the street was finished in 1883.

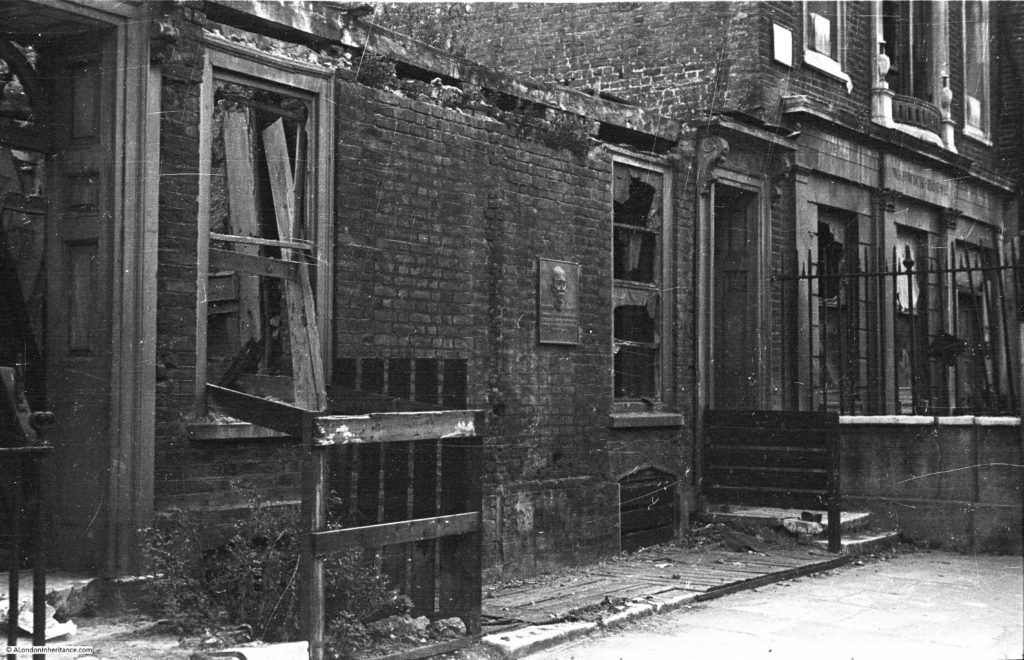

The street suffered some severe damage during the last war when a German bomber crashed into Campden Hill Road, having taken off a large roof in Observatory Gardens, and the crater in the street causing additional damage. A report in the West London Observer on Friday the 18th of April 1941 tells the story:

“London experienced one of the heaviest raids of the War during Wednesday night and early Thursday morning and numerous heavy, high-explosive missiles as well as thousands of incendiary bombs were dropped. Damage was on a large scale and many people were killed.

The German radio yesterday (Thursday) declared that the raid was the heaviest ever on London and the biggest raid of the War, and that 100,000 fire bombs were showered down.

On Thursday morning thousand of Londoners made their way to work over hose-pipes and broken glass, while firemen, begrimed and exhausted, still dealt with the smoldering ruins. Many had to make extensive detours to reach their place of business and thousands found their offices and shops bombed out when they got there.

Altogether five Nazi planes were brought down, one of which crashed in Campden Hill Road, a turning off Kensington High street. Actually the plane hit the roof of a large house in Observatory Gardens before crashing into the roadway about 50-feet away. Bombs from the plane must have crashed into the road in front of this house as there is a very large crater.

The German plane finally came to rest by the side of a large Hostel, part of the University of London.

At the controls was a dead pilot. No traces of other members of the crew could be found, so it is assumed that they had jumped. Later the bodies of two Nazi airmen were discovered in the locality, badly mutilated.

Residents at Campden Hill Road heard the whistle of the approaching aircraft before it crashed. There was no engine noise. Wardens say that it was not on fire.

The bomber touched chimney pots and then disintegrated in small pieces. Its heavier parts, one of the engines and two propellers, landed on the top of a block of flats where some Maltese evacuees were billeted.

An oil tank burst at the same time, and two rooms of the top floors of the flats, which were being used for bedding and linen, caught fire.

During the day, thousands of people passed the spot to see the scattered remains of the bomber. By the afternoon there was little to see as army lorries had conveyed the debris to one of the various scrap bases set aside for this purpose.”

Observatory Gardens was left badly damaged by the crash of the bomber, and as with so many streets across London, the street would not recover for a couple of decades.

In the years after the war, Observatory Gardens became very run down, and it was not until the 1990s that the street we see today emerged. Whilst the exterior of the buildings were restored, much of the interior of the buildings appears to have been considerably rebuilt.

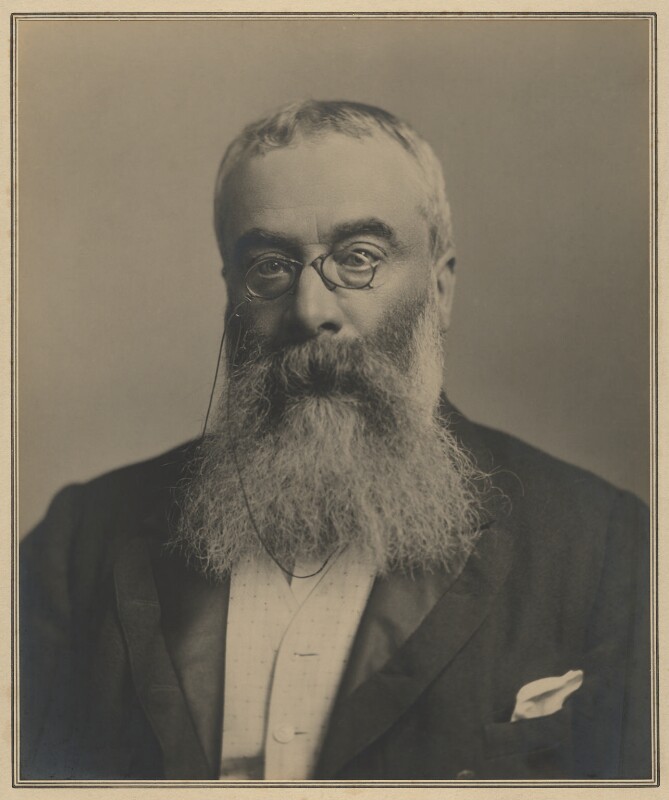

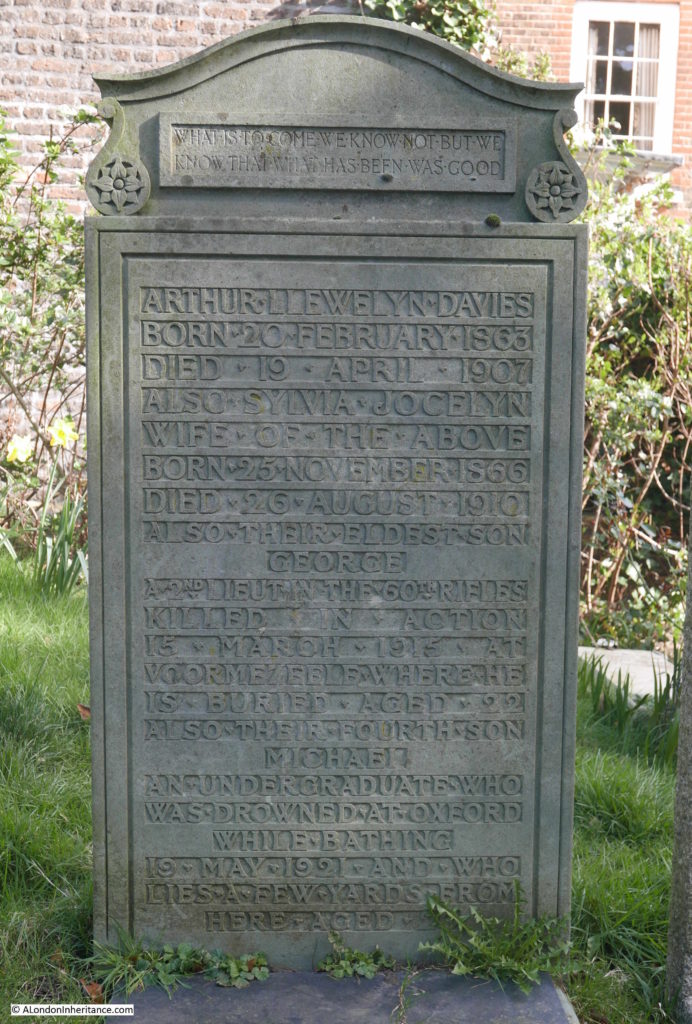

Before Thomas Cawley purchased the land and developed Observatory Gardens, the land was owned by Sir James South, a fascinating character who made astronomical discoveries and also appears to have spent a fair amount of time in the courts.

Sir James South purchased a house and land in 1827 from the Phillimore family, and set about building an astronomical observatory in the grounds.

He started a career as a surgeon in Southwark, and there established an observatory in Blackman Street. He worked with the astronomer John Herschel on the observation of double stars, but he was often difficult to work with, and was frequently drunk.

Despite this, he became President of the Astronomical Society in 1829, but after arguments with a number of Fellows, his involvement with what would become the Royal Astronomical Society faded.

He continued his observations from his house on the land that is now Observatory Gardens, and got involved in a number of disputes with the council who were proposing to extend Camden Hill Road. He believed that the vibrations from traffic on the extended road would impact his telescopes and his observations.

His legal disputes were not just about issues that threatened his observations, he would take legal action on many issues that he daily encountered. One was in 1855 when he took a conductor of a Paddington omnibus to court for deceiving him.

South had apparently hailed the omnibus near King’s Cross and had asked the conductor if it was the Royal Oak omnibus. The conductor confirmed that it was, so South boarded.

The bus continued to Chapel Street by when all the passengers had left the bus, with the exception of South. The conductor stated that the bus would not be going any further than the next stop, and South got into an argument with the conductor regarding the destination of the bus, and that the conductor had informed South that it would go to Royal Oak.

At court, the conductor denied that he had told South the omnibus was going to Royal Oak, stated that South had got on the bus without speaking. Despite this, the court sided with Sir James South and convicted the conductor with a penalty of 20 shillings plus costs.

Whatever the truth of the matter, the case of Sir James South and the conductor of an Omnibus shows that South would take an issue to court no matter how trivial it was, and with the unequal resources and reputation of an omnibus conductor and Sir James South.

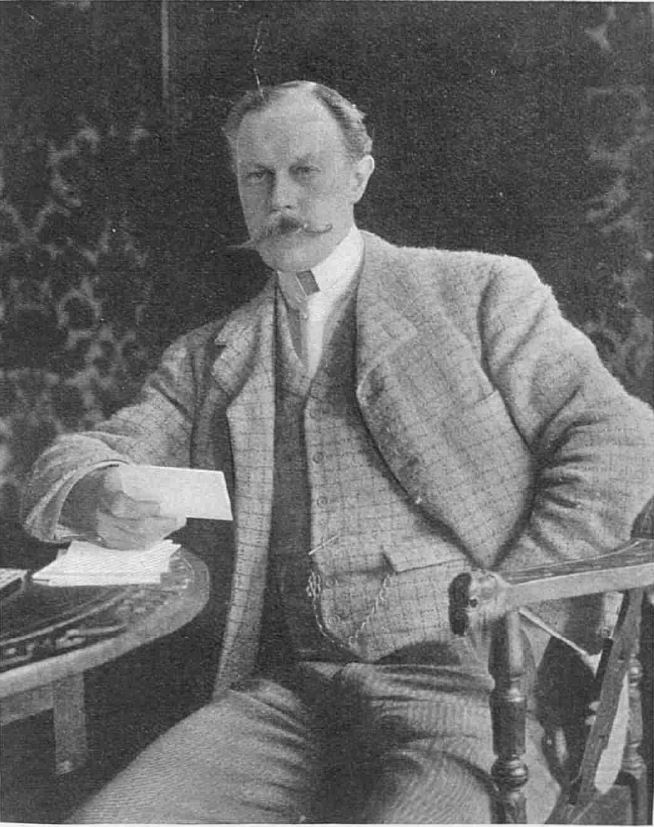

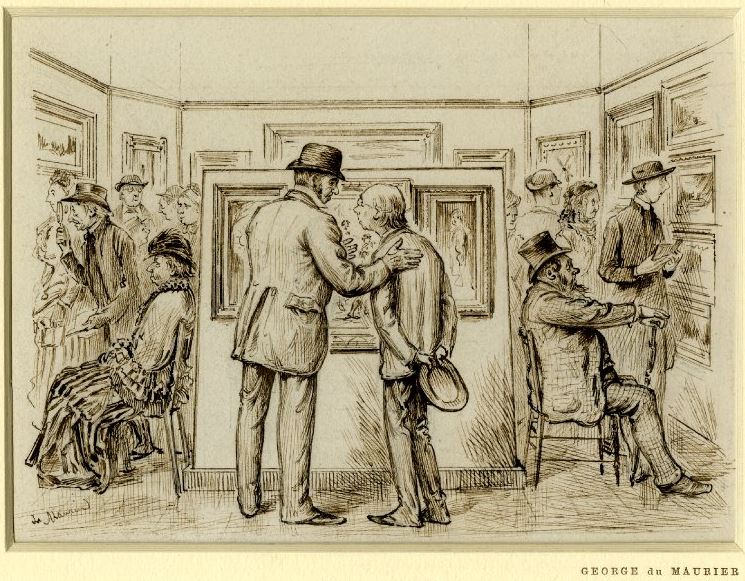

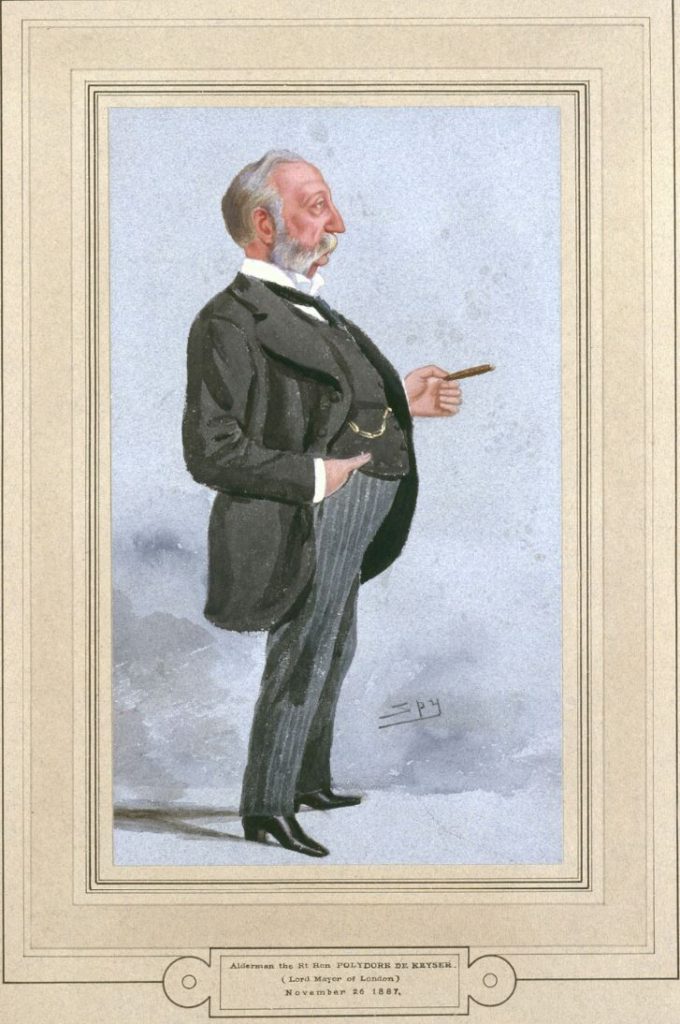

Sir James South:

The Illustrated Times published an obituary for Sir James South on the 26th October, 1867:

“We have to announce the death of Sir James South, F.R.S. at an advanced age. He was the son of a dispensing druggist, who towards the close of the last century carried on in business in Blackman-street, Borough; but James South entered upon a higher branch of the medical profession, and became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons. For some years he practiced his profession in Southwark, and in the intervals in business pursued the study of astronomy, in connection with which he made some extremely valuable observations. In 1822 and 1823, in conjunction with Sir John Herschel, he compiled a catalogue of 380 double stars.

After this he removed to Campden-hill, Kensington, where he constructed an observatory, to which he devoted the closest attention during the remainder of his life, and which has achieved European fame. He was one of the founders of the Royal Astronomical Society, and was for a time its president. In 1830, on the recommendation of the Duke of Wellington, who was then prime Minister, he received the honour of knighthood, and for several years past he has enjoyed a pension of £300 a year on the Civil List for his contributions to astronomical science.

The account of Sir James South’s astronomical observations during his residence in Southwark is published in the Philosophical Transactions for 1825, and is accompanied by a description of the 5 foot and 7 foot equatorials with which they were made. one of these instruments is still mounted and in excellent condition at the Campden-hill Observatory. There are also in the observatory a 7 foot transit instrument, and a 4 foot transit circle. Sir James South was born in 1785.”

The street name Observatory Gardens is therefore named after Sir James South’s observatory that once occupied the land. The following photos shows the end of Observatory Gardens, where the street meets Hornton Street:

One of the newspaper reports I read about the water tower is that the arrival of the Grand Junction Water Works Company, and the resulting reliable supply of water, was one of the reasons why the area developed rapidly during the first half of the 19th century, and that much of that development was of large, ornate, houses.

At the eastern end of Observatory Gardens is Hornton Street, and this is the view looking north – of many of those large, ornate, houses:

And the view looking south, as the hill which gave the area its name continues to descend towards Kensington High Street. Lots more red brick and white decoration:

One thing I realised as I get towards the end of the post is that I have not explained the origin of the name Campden Hill. The Hill element obviously comes from the hill on which the area is built, and that resulted in the water tower being built here. Campden came from Campden House, a large house that was built here by Baptist Hicks, 1st Viscount Campden in the 17th century. The Camden in his title came from Chipping Campden in the County of Gloucester.

In the 19th century and much of the 20th century, there was a considerable amount of infrastructure supporting the provision of water, gas and electricity across London. As with the Campden Hill water tower, so much of this has disappeared, as the technologies used to distribute these services has changed.

Campden Hill is a fascinating area to explore, and I hope this post has provided an indication of what can be discovered across some of the streets.