I have always been fascinated by what is beneath the surface of London and I can trace this interest back to the late 1970’s when I read one of my father’s books “Under London, A Chronicle Of London’s Underground Life-Lines And Relics” by F.L. Stevens and published in 1939. This contained stories of the infrastructure hidden under the streets of London including the Thames Tunnel.

Within this book, there were chapters on the Fleet Drain, Tube Tunnels, Roman London, Crypts and Vaults, Rivers, Wells and Water and Tunnels under the Thames. There is also a final chapter titled “London Takes Cover” which at only 10 pages looks to be a last-minute addition and starts “Queer things are happening under London to-day” and then talks about the preparations being made for Londoners to seek shelter underground from possible terrors on top. I wonder if they could have imagined what would happen to London over the next few years and what those terrors would be?

The chapter on Thames Tunnels starts with Brunel’s tunnel connecting Wapping and Rotherhithe, not only the first tunnel driven under the Thames, but also that the Thames Tunnel was the first tunnel under any river. It was an opportunity to walk this tunnel during closure of the line for maintenance work that I found on the London Transport Museum web site and tickets were ordered.

And so today, Saturday 24th May I was in the queue at Rotherhithe station for the 1:40pm walk through the Thames Tunnel. Blue disposal gloves were provided (there is still a risk of picking up a virus despite a much cleaner Thames. Demonstrates what the risks would have been during construction) Once in the station it was down a short flight of stairs, on to the platform and at the entrance to the tunnel.

The Rotherhithe – Wapping Thames Tunnel was not the first attempt at a tunnel under the Thames. In 1799 a tunnel between Gravesend and Tilbury had been started, given up as a bad job then started again a couple of years later. A shaft was sunk and the tunnel reached within 150 feet of the other side of the river but was again abandoned.

A Thames Tunnel was badly needed. It was a four mile circuit between Rotherhithe and Wapping via London Bridge and ferries carried 4,000 people across the Thames every day at Rotherhithe.

Marc Brunel was convinced that a tunnel could be built and had the concept of a shield to protect workers at the face of the tunneling work. A meeting with investors was held on the 18th February 1824 and a company formed with Brunel appointed as engineer.

The shaft was started in March 1825 and all appeared to be going well, however in January 1826 the river burst through, but work pressed on and by the beginning of 1827 the tunnel had reached 300 feet.

As work progressed, in addition to the risk of the river breaking through, there were all manner of problems including strikes, mysterious diseases (the River Thames was London’s main drain, polluted with a considerable amount of sewage) and explosions from “fire-damp”.

The river continued to burst through. On Saturday 12th January 1828 six workman were trapped and drowned and despite the hole being filled with 4,000 bags of clay the project was temporarily abandoned due to lack of funds. The tunnel was bricked up and no further work carried out for seven years.

Work started again on the 27th March 1835 and carried on for a further eight more years.

In March 1843 staircases were built around the shafts and Marc Brunel led a triumphant procession through the tunnel. Marc Brunel’s son Isambard worked with his father during the construction of the tunnel and was appointed chief engineer in 1827, however his work with the Great Western railway took him away from the tunnel during the later years of construction. Marc Brunel worked on the tunnel from start to finish.

As one of the sights of London, the Thames Tunnel was a huge success. Within 24 hours of the tunnel’s opening fifty thousand people had passed through and one million within the first fifteen weeks.

The Thames Tunnel was purchased by the East London railway in 1866 and three years later was part of London’s underground railway system.

Looking through one of the arches between the two tracks in the tunnel:

Starting from the Rotherhithe end of the tunnel, we walked down the centre of the rail tracks avoiding carefully marked obstructions and walking over small bridges put in to avoid signaling equipment. The tunnel started with a gentle downwards slope towards the halfway point where an upwards slope took us into Wapping station.

Regular archways between the two tracks appeared to be spaced equally the length of the tunnel.

Walking through the tunnel from Rotherhithe to Wapping:

Looking back down the tunnels from the Wapping end. The walk from Rotherhithe was through the tunnel on the right, walk back through the tunnel on the left:

Looking back on an empty Wapping station:

I am glad they turned the power off !! Signpost and distances in the tunnel:

Looking down the tunnel from Wapping:

Original brickwork exposed:

At the Rotherhithe end of the tunnel large pipes with the sound of running water descended below the level of the tunnel. According to the guide, if the pumps that drain this water failed then the tunnel would flood within a matter of hours.

Large pipes at the Rotherhithe end of the tunnel with the sound of water running through them:

All too soon we had returned to Rotherhithe station and it was time to leave the tunnel. A fascinating glimpse of what is beneath London and the challenges of pushing the boundaries of early engineering.

The building that was originally the boiler house during the construction of the tunnel has been restored and is now an excellent small museum. It has a very well stocked bookshop with what must be one of the largest collection of books on Brunel I have ever seen.

The building that was originally the boiler house during the construction of the tunnel has been restored and is now an excellent small museum. It has a very well stocked bookshop with what must be one of the largest collection of books on Brunel I have ever seen.

The following picture shows a mural at the museum which illustrates the shield method of digging used by Brunel. This surrounds the original shaft down to the tunnel. It is now empty and the original stair case long removed. It was originally left open to the skies however fears that tunnel lights would act as guides to enemy aircraft in the 1940’s resulted in the shaft being capped.

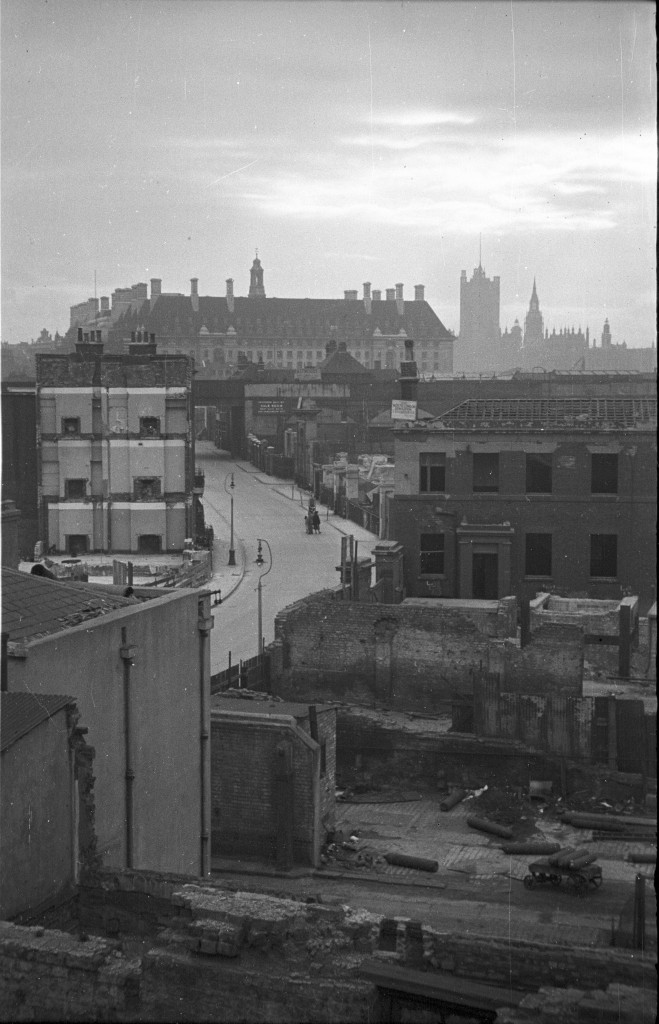

The tunnel passes underneath the paved area outside of the museum and heads towards the Thames.

Just to the north of the museum is a paved area that overlooks the river and provides an excellent view back towards the city.