Somehow, I have reached the end of February 2021 without missing a Sunday post for seven years. I really did not expect to get here when I started at the end of February 2014.

At the end of the 6th year of the blog, the COVID virus was across the news, but had not really affected everyday life. A year of lockdowns and restrictions, and the horrendous death toll were yet to come.

It seems rather trivial given the impact on so many people, however it has been a difficult year for walking and exploring London. Luckily I always have a sufficient backlog of posts to cover periods when getting to places is not possible. I still have very many of my father’s photos which need a visit to research and take a comparison photo. I also had a long list of places to visit, long walks to explore and research to carry out which has just not been possible; hopefully later this year.

One thing I did manage to achieve was pass the Clerkenwell and Islington Guide Course.

Walking and exploring London has been a passion for so many years. Writing the blog is a rather solitary activity behind a computer screen and I have been thinking about how to develop the blog and transferring the blog onto London’s streets seemed a perfect combination.

The course was brilliant and I learnt so much from the lecturers and others on the course, and I have to thank those running the course for managing completion in such a difficult year.

I am working on a number of walking tours covering areas such as the Southbank, Bankside, Barbican, Wapping, Bermondsey, Rotherhithe and Islington and hopefully towards late Spring and early Summer, walking in groups will be possible.

So if you really do want to hear me on the streets of London, unfortunately with even more stories and detail than in the blog, I will announce details in the blog during the coming months.

That is for the future, for now a quick review of the last year.

I have a number of photographic themes which I have tried to maintain for many years. Pub’s, hairdressers (no idea why, but a theme my father started in the early 1980s), closed shops, buildings and places about to be demolished etc.

One theme has been newspaper stands. They fascinate me as they represent a specific moment in time. Newspaper headlines are also very transitory; they seem of the utmost importance at the time, but are quickly replaced by the next days news, and soon fade into history. These stands are glanced at by people rushing by, occasionally picking up one of the papers. They have been a feature of the London streets for many years.

They also tell a story of how an event develops, and so it was with the virus.

The 6th February 2020, outside Charing Cross Station, and the virus still seemed to be restricted mainly to China:

Walking round London that evening and the streets were as busy as normal – outside Green Park station in Piccadilly:

Another photographic theme is tracking down some of the hidden views of London. There are so many places which are not normally visible simply walking the streets.

If you walk down Allsop Place, off the Marylebone Road by Madame Tussauds, there is a point where the row of buildings along the street ends and a high brick wall fills the gap. The wall is just too high to look over, but hold your camera above the wall and a hidden world opens up:

Part of Baker Street station is visible, the brightly lit platforms surrounded by the dark walls of the surrounding buildings. In February the underground system was just as busy as usual.

On the 21st February, a news stand in Piccadilly was warning that the killer virus was now spreading fast:

Despite warnings that the virus was spreading fast, by the 27th February, the country’s borders were still wide open and large sporting events continued to go ahead, mixing supporters from home and abroad.

Arsenal were playing Olympiakos in the Europa League on the evening of the 27th February. This was the home match, with Arsenal going into the game with a 1-0 advantage following a win in Greece the previous week.

Olympiakos would go on to win 2-1 and knock Arsenal out of the Europa League. As with any London game, the away fans from Olympiakos were in central London before heading out to the Emirates Stadium and when I walked by, they were loudly clustered in Piccadilly Circus.

Other news did continue to make the headlines, and on the 6th March a “Hammer Blow For Heathrow Runway” was reported:

This referred to a court of appeal decision that the Government’s decision to go ahead with the runway was illegal as they had not considered their climate commitments in coming to a decision.

This decision was overturned by the Supreme Court last December, meaning that the third runway can now move forward to the planning permission stage.

Whether the impact of the pandemic on air travel and the finance of airport operators will influence the need and business justification for a third runway remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, commuters at Waterloo Station were still dashing from Underground to station concourse for the train home as the “Virus War Enters Next Phase”:

On the 12th March outside Great Portland Street station, there was an appeal as the “Country Needs You To Join Virus Fight”:

But on Sunday 15th March, the previous Friday’s headlines were hinting at the coming lockdown, and that the lockdown may risk even more deaths:

Headlines continued in much the same way, and on the 23rd October, headlines had shifted from the risk of the virus to the help needed to overcome the restrictions and challenges of lockdowns:

When a packed underground train was a normal expectation, travelling on the underground, even out of lockdown, was a rather strange experience. Having an empty train carriage became a common, rather than an exceptional event.

And empty stations – this was Highbury & Islington Station at 3:55pm on Saturday 24th October 2020:

Even before the first lockdown in March, the streets were empty. Outside the Natural History Museum:

Piccadilly Circus – so much quieter than when Olympiakos fans had gathered there less than a month before:

Trafalgar Square:

Travelling across Tower Bridge:

Piccadilly:

I mentioned earlier that pubs are one of my photographic themes. I had long planned to walk around the City to find and photograph all the pubs, and in July 2020 I spent a day doing just that. The majority were still closed, having been closed since the start of the March lockdown. Tiered restrictions and the lack of workers and tourists in the City meant there was no point in reopening – customers were just not there. This continues to be the situation, and even when restrictions are reduced there will probably be a considerable delay until there are sufficient people back in the City to make the number of City pubs economic.

One pub that will not reopen is the Still and Star in Little Somerset Street.

The Still and Star is the one remaining “slum pub” and has been under threat for some years, however in December 2020, the City of London Corporation approved revised plans for a 15-storey tower to be built on the land in Aldgate High Street, including the space occupied by the Still and Star.

The new plans include a “reimagining” of the Still and Star with a new pub built facing onto Aldgate High Street. A very sad loss of a one off City pub.

In August, I climbed the O2 Dome with my 12 year old granddaughter, something that she had wanted to do for some time. In the following photo, the view is looking across to the water of the Royal Victoria Dock. It looks almost certain that the new “City Hall” will be the low, long building to the left.

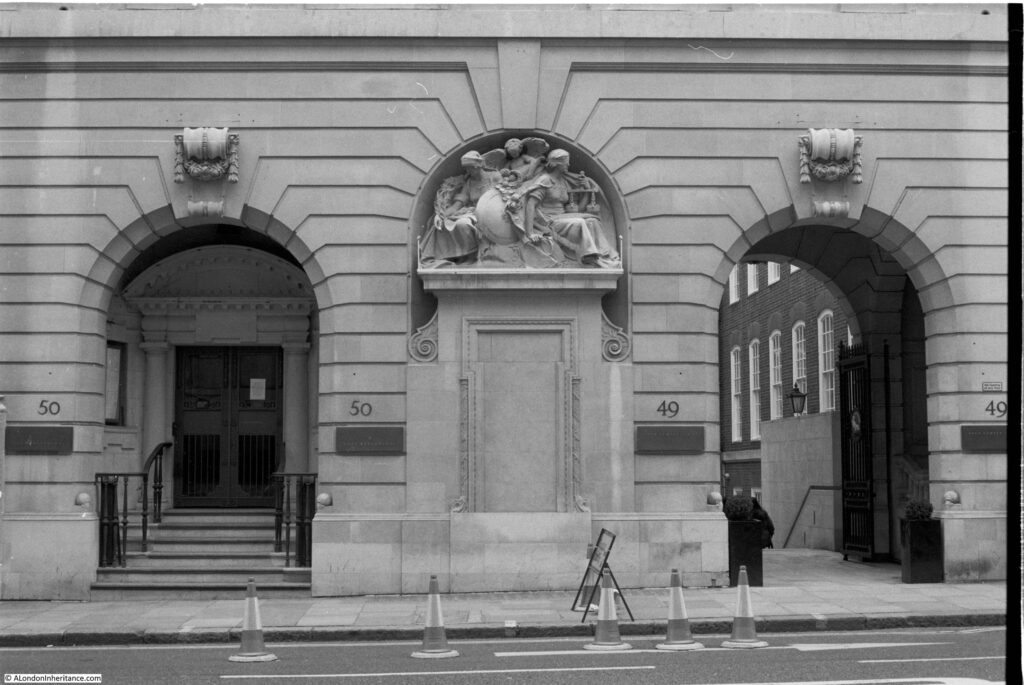

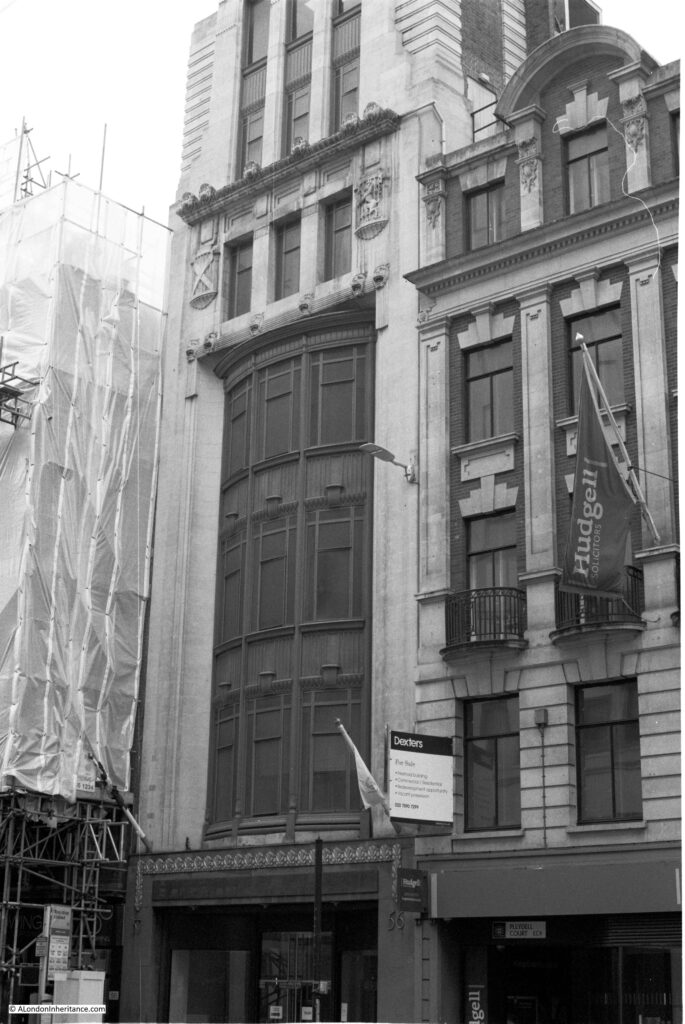

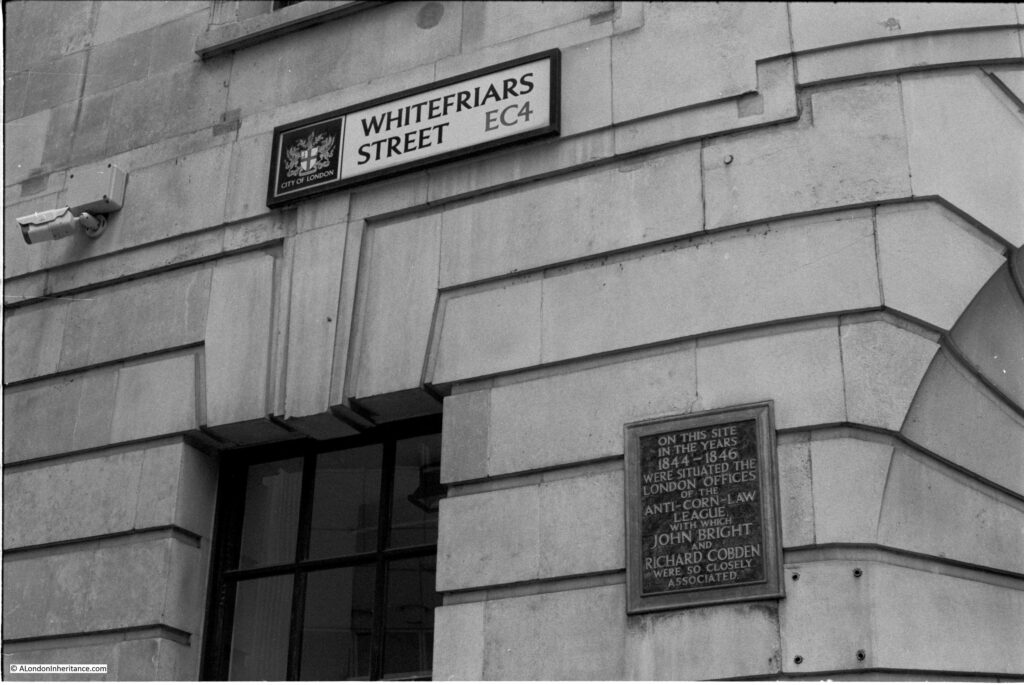

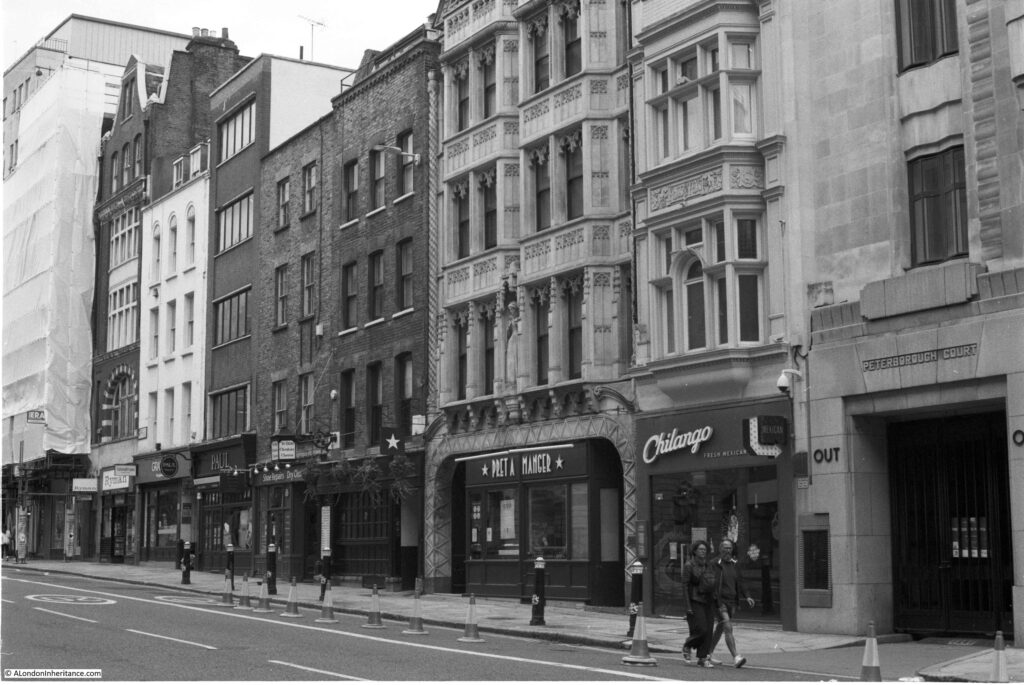

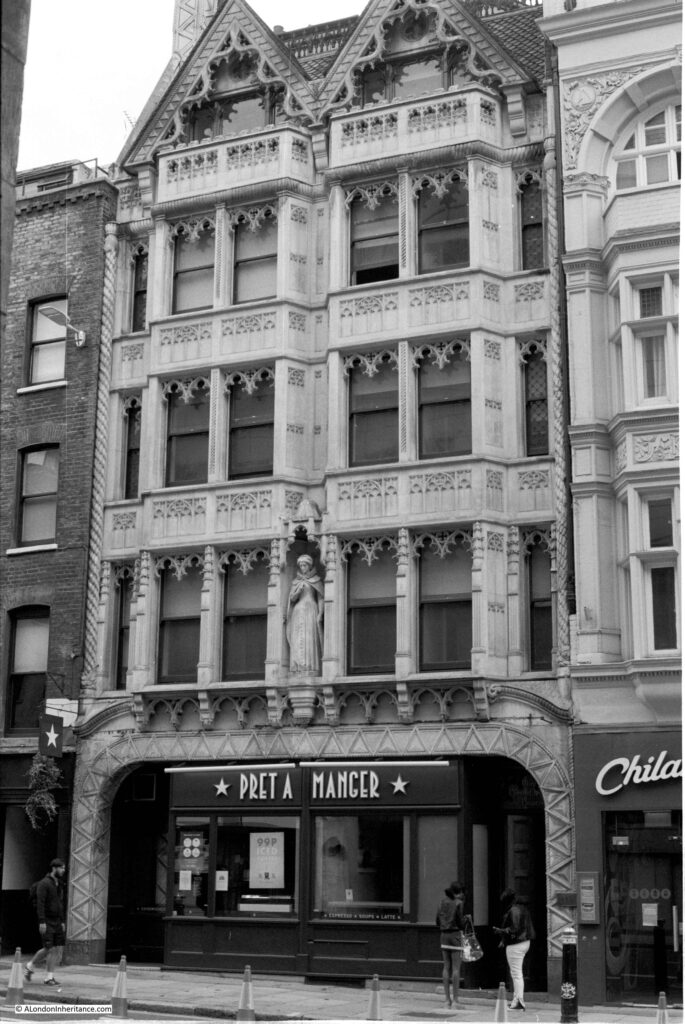

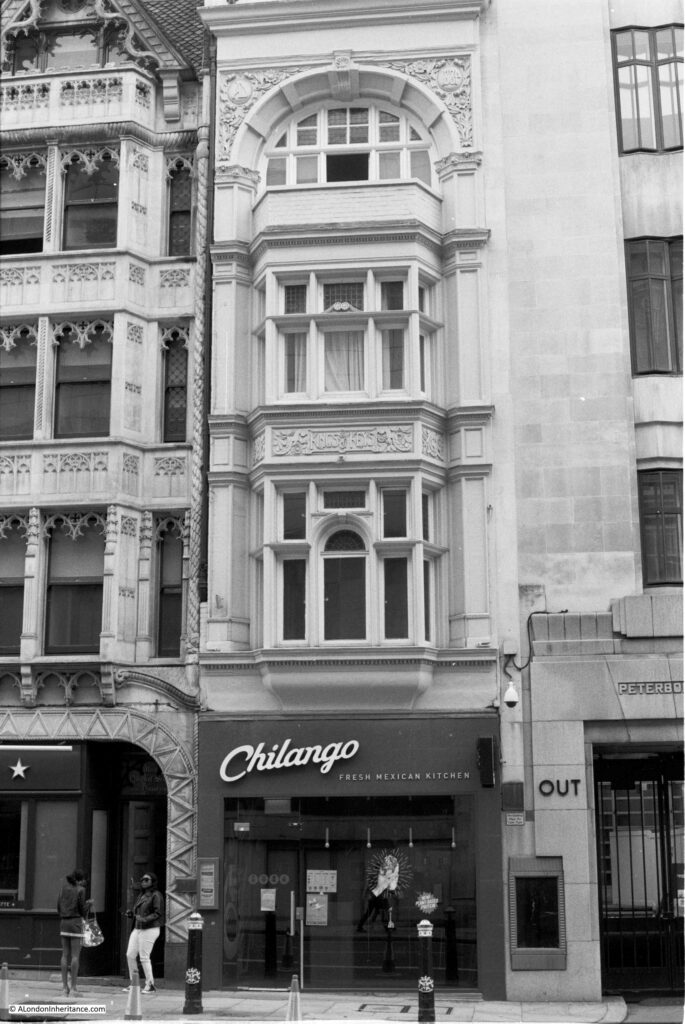

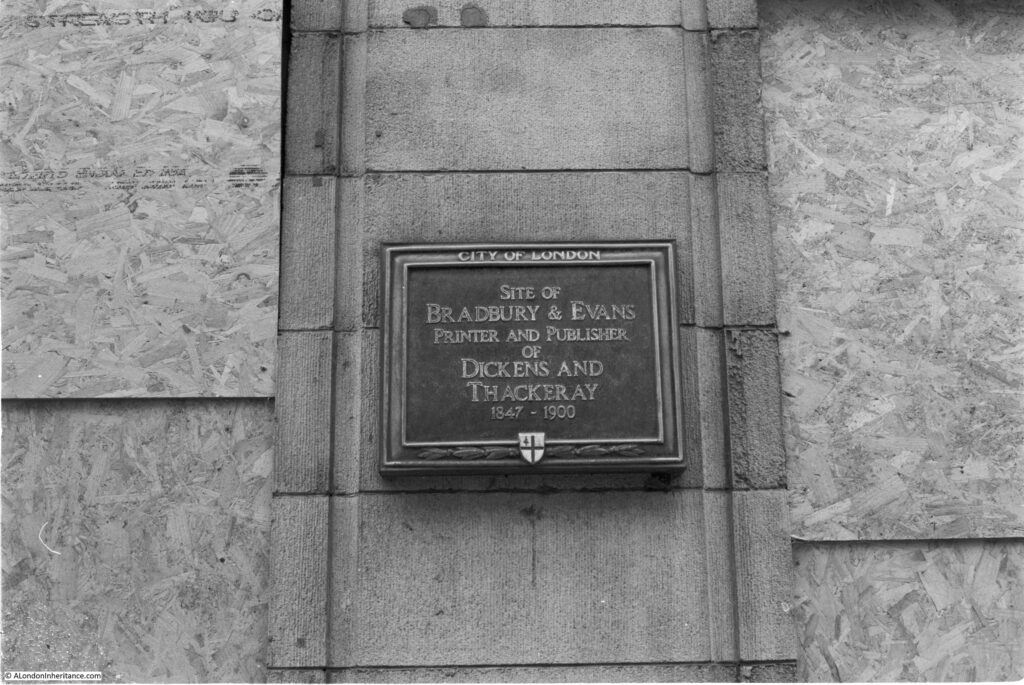

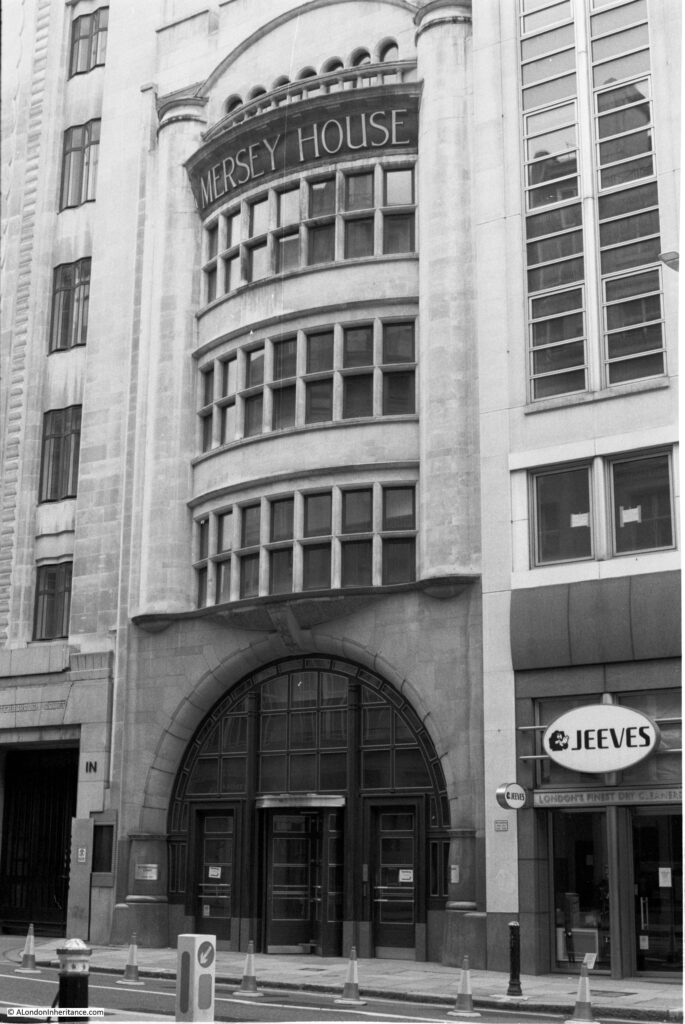

In 2020 I finally managed to take my father’s old Leica IIIg camera out for a walk around London. The camera that was used for the 1950s photos in the blog, and the lens that was used for all my father’s photos from the 1940s and 50s.

The camera was last used towards the end of the 1970s and needed a repair to fix a sticking shutter, but I was really pleased with the first photo after more than 40 years.

As lockdown ends I will be ordering more black & white film, and an attempt at developing my own films is the next challenge.

I also continued to revisit some of my early photos, including the following photo of the Globe in Borough Market which I had taken in 1977:

The same pub in 2020:

In October, the City was still quiet:

The view down Ludgate Hill from St Paul’s on a Saturday afternoon:

Two of the businesses hit the most by the lockdowns and lack of people in the City – travel and hospitality:

City Thameslink Station:

The majority of my posts were not about the impact of the virus, and my most popular post of the year, in terms of the number of times the page was viewed, was my post on Broad Street Station, a station I had photographed in 1986, not long before the building was demolished:

The same view today:

Whatever happens after the pandemic, London will reinvent and thrive, as it has done so many times before, and it will continue (in my fully biased view) to be the best city in the world to walk and explore.

There will be differences. More home working and reduced numbers of people working 5 days a week in the city. Sir Peter Hendy, chairman of Network Rail has predicted that leisure and holiday travel by train is set to increase, while commuter traffic is likely to continue to fall.

Hopefully many of the trends that have had a negative effect on living and working in the city will change, such as the sale for overseas investment of so many of the flats and apartments being constructed, and there needs to be a reduction in the cost of housing in London.

London also needs its local facilities. it needs local areas with their own specific identity. Some of the recent changes in Soho risk the destruction of the identity of a unique and historic area.

Crossrail (the Elizabeth Line) will finally open. The Museum of London move to Smithfield opens up so many opportunities (and risks) to the area, however the proposed concert hall that was to take the museum’s place at the Barbican has been cancelled due to “unprecedented circumstances” and will be replaced by an upgrade to the Barbican complex.

The upwards growth of the City does look to continue, with at least five new glass and steel towers being planned.

At the end of the 7th year, can I thank you so much for reading the blog. I learn so much from the comments and am grateful for the corrections when I (thankfully not that often) get something wrong. There is a considerable amount of knowledge and experience of London out there.

I also hope that later in 2021 I get the opportunity to take you on a walk around some of the places I write about and show more of the history and stories of this fascinating city.