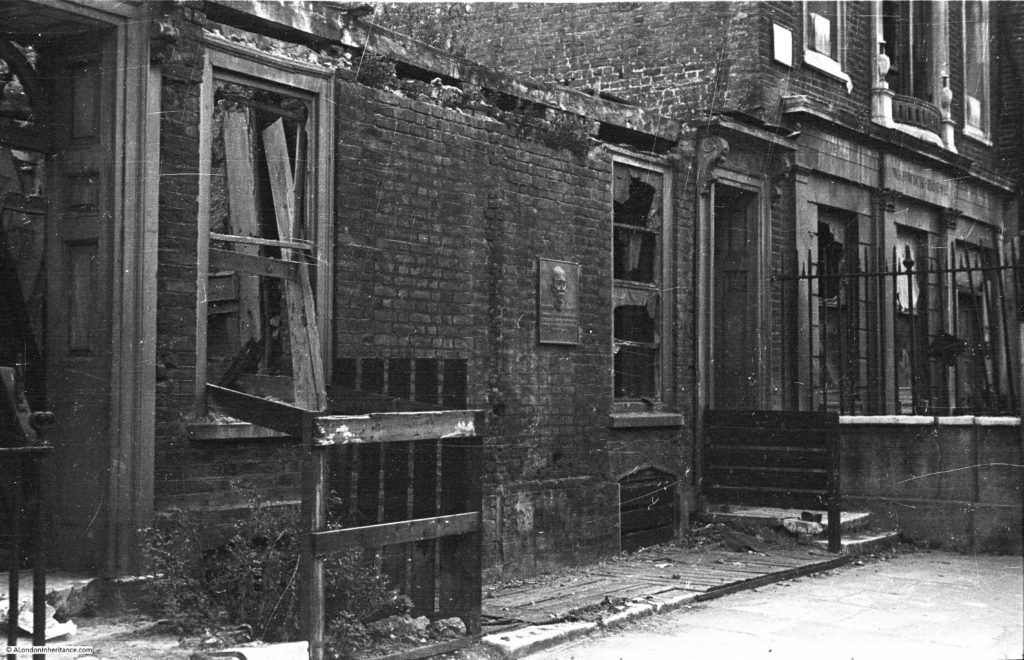

The subject of this week’s post is another post war photo taken by my father showing a bombed building with only the lower part of the front facade remaining.

The one distinguishing feature is the plaque on the remaining wall. The location is Gray’s Inn Place, a small gated area within Gray’s Inn. The gate separates Gray’s Inn Place from Warwick Court which leads down to High Holborn.

The same location today:

The building on which the plaque is now mounted is the City Law School. The building to the right is the same in both photos and appears to have been faithfully restored with the majority of the external features remaining the same.

The wall and railings in both photos also appear the same, confirming that the physical separation of Gray’s Inn from the local area has been in place for many years.

The plaque is to Sun Yat-sen and given that it appears to be undamaged in the post war photo, I have no reason to doubt that it is the same plaque in place today.

Sun Yat-sen is recognised as the father of the Chinese Republic and is honoured in both China and Taiwan. I am not going to attempt to explain his role in the complex Chinese politics of the time. I have read a number of histories and chronologies of his life on the Internet and it would take a much better understanding than I have of Chinese history at the end of the 19th Century and start of the 20th to try and explain his role. The key fact is that he was the first President of the Chinese Republic and worked to bring about a modern approach in a country that had been under Imperial rule for many centuries. In this post I will focus on his brief time in London and the affair that made headlines in the country’s newspapers in 1896.

Sun Yat-sen originally studied medicine at a college in China run by a Dr James Cantlie and qualified in 1892. Sun was also involved in a number of political activities including a coup attempt in 1895 which went wrong and resulted in Sun having to escape from China and a long period in exile.

In 1896 he arrived in London where he again met Dr James Cantlie who had returned to London in 1895 and it was Cantlie who arranged the lodging in Gray’s Inn Place for Sun.

The impact of Chinese politics extended to London. Sun would walk regularly to study in the British Museum and also to visit Cantlie and whilst on one of these walks on Sunday October 11th 1896, close to the Chinese Legation in Portland Place, he was tricked by some Chinese men into entering a building which was part of the Legation.

Cantlie received word of Sun’s imprisonment at the Legation and started to campaign for his release trying both the Home and Foreign Office and the newspapers, initially with The Times (who did not appear interested and would not publish the story) to The Globe who did publish with such graphic headlines that it resulted in the Government taking action, and Sun being released on Friday 23rd October 1896.

The Globe article on the 23rd October was titled “The Kidnapping Case” and read:

“We have received information this afternoon of the fact that depositions reached the Home Office yesterday to the effect that Sun Yat Sen was detained at the Chinese legation, and these were immediately communicated to the Foreign Office. Lord Salisbury has, in consequence, addressed a request to the Chinese Minister for the immediate release of the prisoner”.

The Globe article also included Dr. Cantlie’s statement which makes for a fascinating read of what was happening on the streets of London in 1896:

“A representative of “The Globe” called to-day at the house of Dr. James Cantlie, Dean of the College of Medicine for Chinese who is the friend of Sun Yat Sen, referred to in the accounts of the kidnapping case which has been published. Dr. Cantlie had drawn up a full statement of the affair which the following is the substance:

Sun Yat Sen says the Doctor is a Chinese friend of mine, and has been detained in the Legation since last Sunday week. I knew Sun in Hong Kong intimately. He studied medicine at the College there, at which I was a lecturer, from the year 1887 until he qualified. He was a brilliant student and started to practice in Macao, a settlement some 13 miles from Hong Kong. He was, owing to the success which attended his practice there, induced by his friends to go to Canton. I then lost sight of him for some months, but fortunately he called upon me in Hong Kong, and said he had got into some trouble with the Chinese government. I recommended him to consult a lawyer. I saw a lawyer the next day, but he would not tell me where Sun was, in case the news should get about. I next saw Sun in Honolulu, on my way home in March of this year.

I found he was going England, and I urged him most strongly to prosecute his medical studies in England, and advised him to come to London in October, when the medical classes opened.

This he did for he called upon me in London on the 1st October. He spent the day with me at my house. I then found lodgings for him for a few days. He came backwards and forwards to my house, but suddenly his visits ceased, and I learned from his landlady that he had not been seen at his lodgings for a few days.

On Saturday evening, October 17th at 10:30 I received information from a source there was no gainsaying that Sun was a prisoner at the Chinese Legation, and that in a few days he was to be sent out to China, where he would certainly lose his head. I immediately went to Sir Halliday Macartney’s house at 3, Harley-place, but the house was shut up, and the constable on duty in the road told me they had gone away for six months. I then went and reported the matter to the Marylebone Police station. Not receiving any offer of immediate help, I then went to Scotland Yard and laid the matter before the authorities.

On Sunday, October 18th, I again called at 3 Harley Place in the hope of finding a caretaker from whom I might get Sir Halliday’s address. Not gaining admission, I went to seek the advice of Dr. Manson, as he knew Sun while his pupil, and who had seen him at his house in London a few days previously. Whilst I was there we received confirmation of the previous night’s report from another source. This was communicated in, if possible a still more definite way and we were able to get at the truth.

A note from Sun placed the matter beyond all doubt, especially as his handwriting is familiar to us. Dr. Manson took the case up, and we went to Scotland Yard to report further particulars. Afterwards we called at the Foreign Office and reported the matter there. Dr. Manson then called at the Chinese Legation and asked for Sun. He was told there was no such person there, and he then told the Chinese that we knew Sun to be there, and the fact of his detention had been communicated to the Foreign Office and the police,

We then had the further satisfaction of knowing that should the Chinese ascertain that something had leaked out, Sun light be saved. I posted a private detective to watch the Legation, in case an attempt should be made to smuggle him away in the night. Our information was that he would be smuggled away and that in all probability the attempt would be made on Tuesday, the 20th.

The time at our disposal was so short that we did not know how best to obtain protection. On Sunday night, October 18th, I called at the office of the Times and reported the matter there, asking if they thought it better to delay publication of the news until it was seen how things would turn out. On Monday 19th, I had again a private detective employed in watching the house. I kept him there until Tuesday, when I removed him, as I learned that a Scotland Yard official had taken up the duty of watching the premises.

Since then I have had surreptitious communications from Sun. and have been able to convey a message to him, stating that Dr. Manson and my self were doing everything possible to secure justice. He had taken his food better since and has also slept better. He was afraid to eat previously, being in the greatest dread of Poison. At one time he threatened to commit suicide, but our communications allayed his fears. His guards have been doubled since the Chinese got to know the circumstances, and his window has been secured, as it was found that he was writing notes and throwing them out the window. The endeavor to obtain his release, I believe proceeded satisfactorily, and unless deferred hope causes him to give way to extreme measures, all may yet be well.

Sun thus briefly describes the procedure of his capture. Whilst passing the Chinese Legation on his way to my house, on October 11th, he was accosted by two China men, who quietly go on either side of him, and, as they were opposite the Legation, hustled him in and locked the door. He was then pushed into a room by an English gentlemen, who locked his door, and stationed a guard over it. The report given out by the Chinese Legation that Sun is a lunatic is ridiculous, but it was on that pretence that his passage was engaged on board a vessel that was to take him to China.

The latest report from the Legation is that the Emperor of China does not want Sun now,

At one time in this singular affair it was put in our power to effect a rescue. we were sorely tempted to do this on being constantly met at the legation with the direct lie that Sun was not there. Considering however, the slur cast upon the laws of this country by the Chinese, we thought, and were advised, that it would be more in keeping with the dignity of British law that justice should be more effected through the ordinary channels.

When the matter is concluded and Sun is set at liberty, I will ask the public to reward my informants, who have, no doubt, been the direct means of saving a man’s life. they made the communication at great personal risk and sacrifice.

(Signed) James Cantlie. M.B., F.R.C.S”

After his release from the Chinese Legation and the threat of certain execution had he been smuggled out to China, Sun continues to spend many years in exile, travelling the world to gather support for his cause, before finally events in China allowed him to return on January 1st, 1912.

On May 5th 1921 he was sworn in as President of the Republic of China, something that would not have been possible if not for the efforts of Dr. James Cantlie in London in 1896.

Returning to Gray’s Inn Place, I cannot find a date for when the plaque was made and installed, but it must have been pre-war. It was made by the Estonian sculptor Dora Gordine who moved to London in the early 1930s, so I suspect the plaque was made between then and 1939.

Dora Gordine married Richard Hare and set up a studio home at Dorich House in 1936, which Dora had designed, near Richmond park. The house is now the Dorich House Museum.

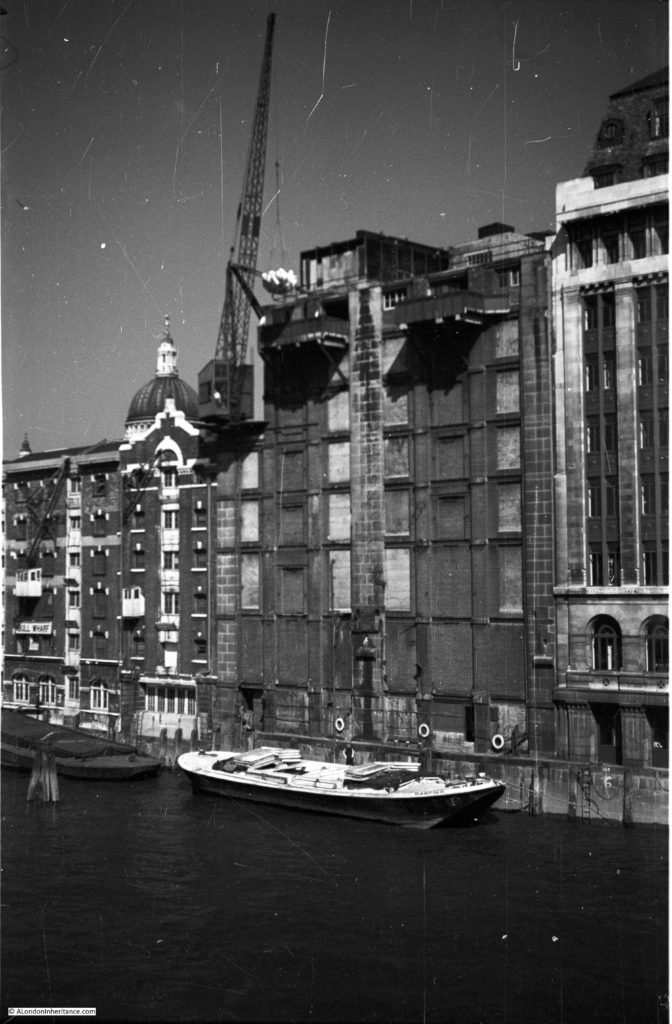

The following photo shows the house at the end of Warwick Court, next to the building on which the plaque is mounted. Compare this with the post war photo and as well as the main features of the building, there are a couple of other survivors.

On the first floor, to the left of the central window is a Hydrant sign which was in the pre-war photo, where there was also a plaque on the extreme left of the building at the same level. Whilst the plaque is not there, the outline of the plaque remains. I wonder if this was the Gray’s Inn boundary marker (dated 1697) now on the second floor the house.

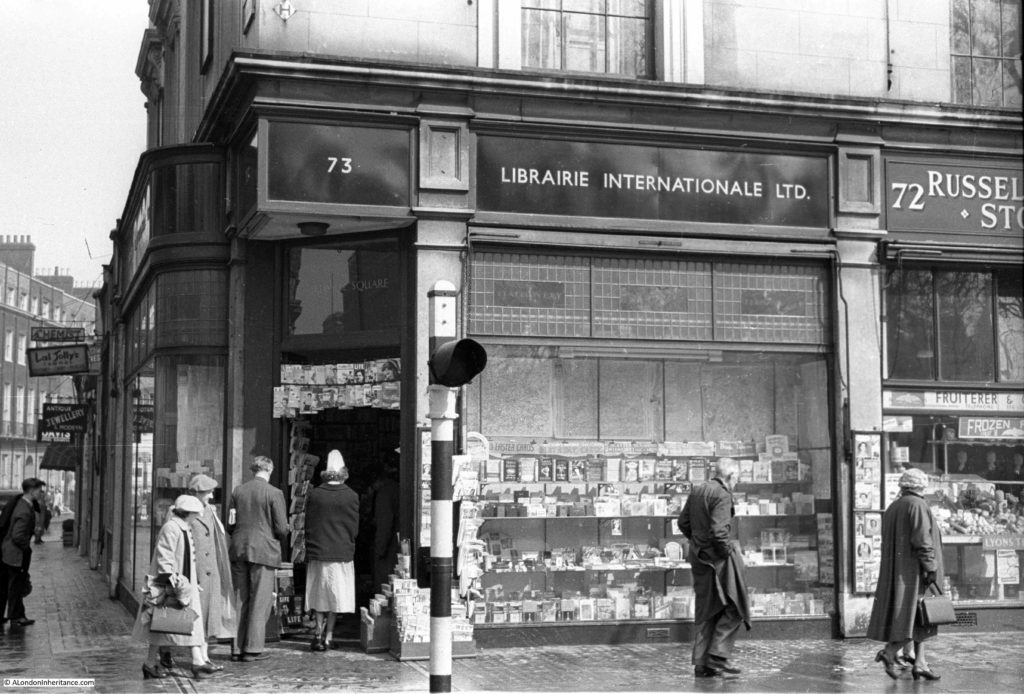

The best place to see the plaque is in Gray’s Inn. If you walk up Warwick Court and entrance is closed, you can still see the plaque on the wall to the right. Even here, the conversion of so many London buildings to luxury apartments continues.

The following photo shows the entrance to Gray’s Inn Place today.

A fascinating story of a London kidnapping, a story that I did not know about until I found the location of my father’s photo of a bombed building and a single plaque that had survived the considerable damage inflicted on Gray’s Inn.

There is a chronology of the life of Sun Yat-sen on the web site of the Dr. Sun yat-sen Memorial Hall in Taipei.