The three volumes of “Wonderful London”, published in the 1920s contain a fascinating photographic record of the city at the start of the 20th century. Many of the scenes are recognisable today, however many have also changed beyond all recognition, and offer a glimpse of a way of life before being swept away during post-war redevelopment. One of these photos is of Pennyfields, Poplar.

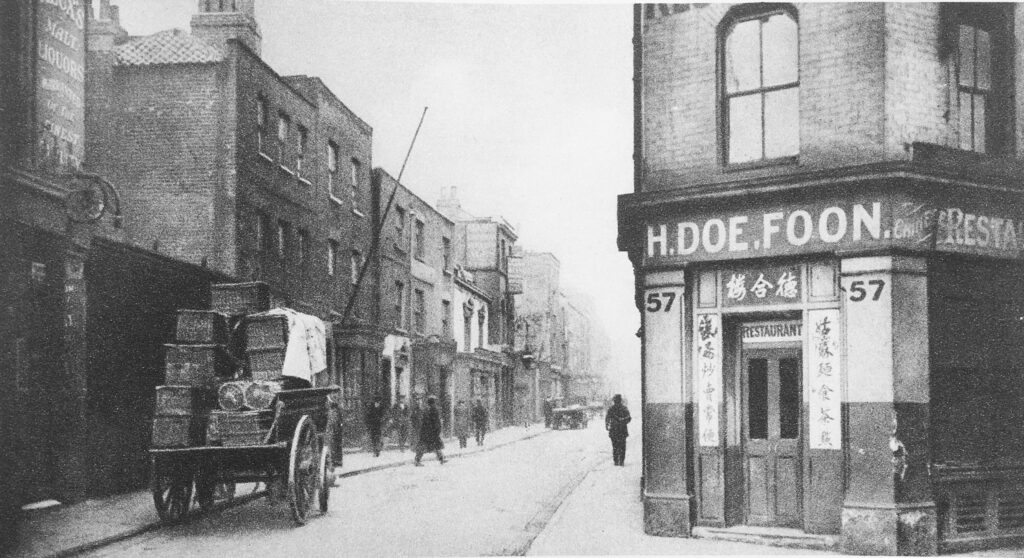

The photo is titled “Gloom and Grime in the East End: Chinatown”, and has the following description: “A view of Pennyfields, which runs from West India Dock Road to Poplar High Street. There is a Chinese restaurant on the corner. A few Chinese and European clothes are all that are to be seen in the daytime”:

The same view today (March 2022):

The only surviving feature between the two photos which are around 100 years apart (although Wonderful London was published in 1926/7, the individual photos are not dated), is the street, Pennyfields, which runs from West India Dock Road (where I am standing), to Poplar High Street.

There are a number of features in the Wonderful London photo, two pubs on the left of the street, and the Chinese restaurant on the right, and the following graphic shows the position of these on the street today:

Pennyfields still runs between West India Dock Road and Poplar High Street, and I have circled the street in the map below (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Pennyfields, and the surrounding area, changed dramatically during the 19th century. At the start of the century, there was still a considerable amount of open space, however the arrival of the West India and East India Docks would drive the development of the area, and by the end of the 19th century, the land around Pennyfields was covered in dense terrace housing along with the infrastructure needed to serve the docks.

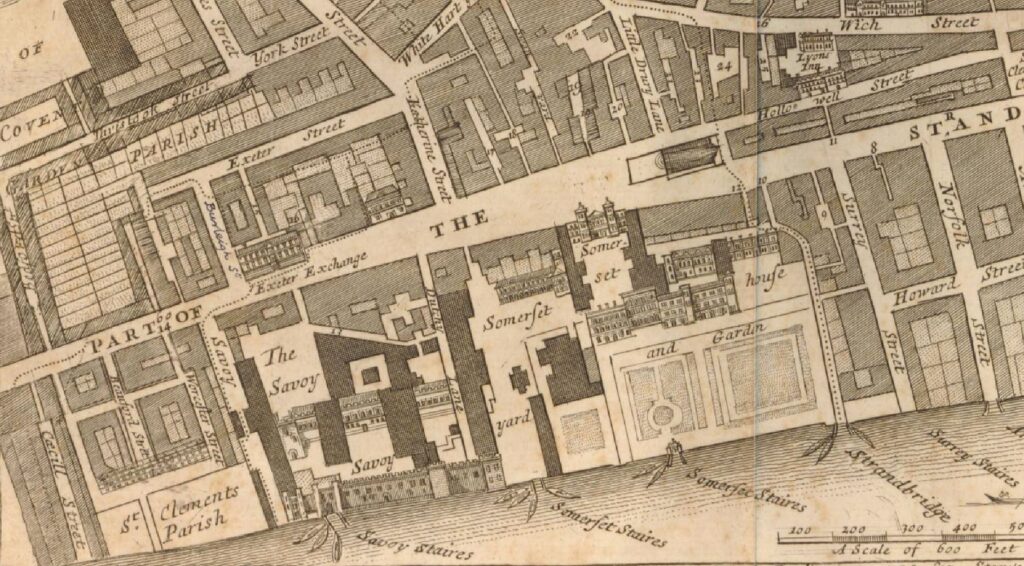

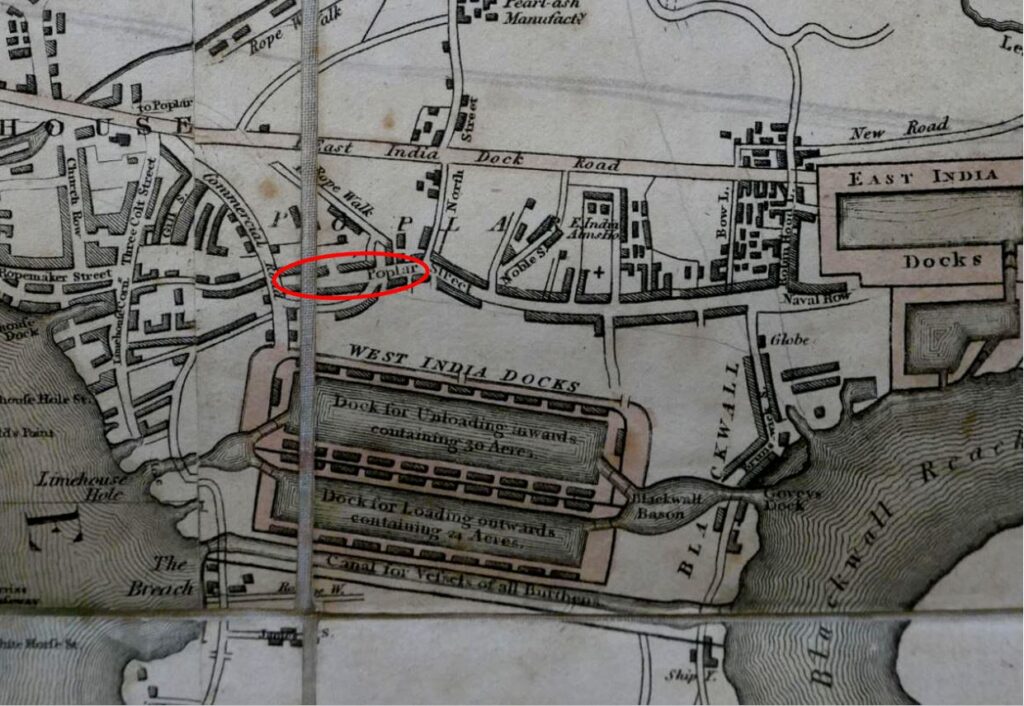

The following map is from Smiths New Plan of London, dated 1816. Pennyfields is not named, and appears to be a westward continuation of Poplar High Street:

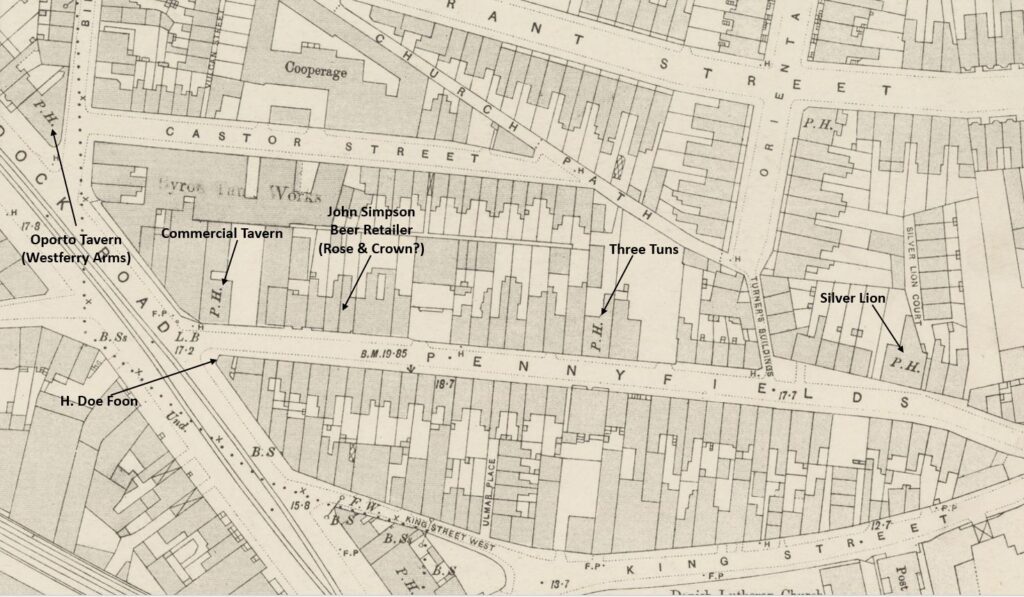

And by the time of the 1895 Ordnance Survey map, Pennyfields is named, and the whole area is built up (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

I have marked a number of features in the above map. H. Doe. Foon is the Chinese restaurant on the corner. Note that the shape of the building in the above map is the same as the building in the photo. The restaurant also has the number 57. This was 57 West India Dock Road, not Pennyfields.

As with any east London street of the late 20th century, there are a number of pubs.

The pub that can just be seen on the left of the Wonderful London photo was the Commercial Tavern. Not seen in the photo, but to the upper left on the West India Dock Road was the Oporto Tavern.

In the Wonderful London photo, there is what appears to be a pub, with a large lantern outside. This is not marked as a Public House on the Ordnance Survey map, but I believe from checking street directories, that this was the premises of John Simpson, Beer Retailer, and would later become the Rose and Crown.

There are two more pubs along Pennyfields, not seen in the photo, the Three Tuns and the Silver Lion are marked on the map.

I will start a walk through the area just north of Pennyfields, at the Westferry Arms in West India Dock Road. In the 1895 OS map, I have marked the pub just north west of Pennyfields as the Oporto Tavern, and today it is the Westferry Arms:

The pub was originally the Oporto Tavern and changed name to the Westferry Arms around the year 2012, presumably named after Westferry Road which starts almost opposite the pub, along with Westferry DLR station.

The first reference I can find to the pub is from 1864, when the pub was advertising in the Morning Advertiser for a potman, so I suspect the pub was opened around 1860.

The pub was just a short distance north of one of the main entrances to the West India Docks, and was popular with those who worked at the docks as well as those who arrived by ship.

Bill Neal, who had been landlord of the Oporto Tavern for thirty one years when he died in 1951 and was such an institution that his death resulted in an article in the national Daily Mirror, an article which describes a way of life that would soon change for ever:

“The Juke Box is silent now in the pub where the sailors go – Before dawn came to London’s Covent Garden yesterday they were seeking out the most fragrant, whitest lilac and later, down in the West India Dock-road, Chinese were searching for black-edged handkerchiefs of mourning.

For Bill Neal is dead. Bill who for thirty-one years stood behind the bar of the Oporto Tavern in the West India Dock-road, only a few yards from the gates of the docks that lead seafarers to faraway places.

Bill was the seamen’s first port of call. He cared for the money of the wise ones who were determined to blot out their cares in drink. He was a soft touch for a free meal. Legend has it that he once even gave away his boots. But he could throw out the noisy drunkard quicker than any other landlord.

A man walked sadly into the saloon bar yesterday and stuck a slip of paper over the slot of the juke-box.

For the rest of the week, visiting seamen will not hear the music they love – for Bill Neal is dead.

And in the bar where Bill reigned for so many years – above the song song of the Chinese barbers and laundrymen, and the voices of the Limehouse Cockney, one voice was clear this morning.

It was that of the Rev. H. Evans, vicar of St Matthias, poplar, who stood where he had so often stood to have a chat with Bill. He was the ideal Christian, Mr. Evans said, he thought of other people and never of himself. Other people say he was foolishly generous.

In the decades after Bill Neal’s death, the docks would close and the seamen would disappear, and today the tower blocks of flats that are typical of new building on the Isle of Dogs have reached to the opposite side of the West India Dock Road:

The Westferry Arms closed in 2016 after a number of years when the pub attracted the drugs trade and also many complaints of noise, which is rather strange given how close the pub was to the (also now closed) Limehouse Police Station, which was a very short distance further north.

In 2015 there was an application to review the premises licence for the Westferry Arms, and reading through it is almost comical, where “whilst in the yard of the Limehouse Police Station, Police Officers smelt a strong smell of cannabis in the air coming from the direction of the Westferry Arms Public House.”

The request to remove the pubs licence was turned down, however this was on the basis that the pub would implement a number of new measures to address the sale and use of drugs and to restrict noise and outside drinking. The request was also turned down at the licensing sub-committee as members “were very concerned about the lack of action taken by the Police despite the premises being just meters away from the Limehouse Police Station”.

Today, the Westferry Arms is closed, with metal grills protecting the ground floor doors and windows:

In 2020 a planning application was approved to demolish the Westferry Arms, and build a new nine storey tower, with the basement and ground floor being available as a pub, and the upper 8 floors consisting of a mix of one, two and three bedroom flats.

No indication of when demolition will start, and while the Westferry Arms / Oporto Tavern waits, it reflects that even if the ground floor of the new development opens as a pub, it will never see the likes of Bill Neal, Dockers or seamen from around the world again.

Just to the right of the pub is Birchfield Street. I noticed one of the wonderful London County Council plaques on the side of Birchfield House:

Birchfield House was the result of the only LCC slum clearance project in Poplar in the 1920s, and became part of the much larger Birchfield Estate during post war slum clearances, and redevelopment of bomb damaged buildings.

The following photo is looking back at the terrace of shops and flats where Pennyfields meets the West India Dock Road. The Commercial Tavern which can just be seen in the Wonderful London photo was at the far end of the terrace, where the blue / green shops are located.

The terrace of shops appears to date from the 1970s and were built following the clearance of buildings along this stretch of the street, which included demolition of the Commercial Tavern.

The closed and shuttered Pennyfield Launderette:

The next pub in the street is a bit of a mystery. In the Wonderful London photo, there appears to be a pub further down the street. It has large signs on the façade and a large hanging lantern over the street. It is a narrow building with only two horizontal window bays.

The 1895 OS map does not mark the building with the PH letters for a public house, however reading through street directories in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the occupation of the owner is listed as “beer seller”.

Checking for newspaper references and there are a number at the end of the 19th century to the “Rose and Crown beerhouse”. It is not identified as a public house.

The difference is down to the 1830 Beer Act, which defined a beer house as a premises which was only licenced to sell beer, and could not sell wine, spirits etc. So a public house could sell the full range of alcoholic drinks, and the beerhouse, only beer.

A later incarnation of the Rose and Crown can be found on Pennyfields today.

The original building lasted until the 1950s. Whilst the rest of the street was being purchased by the LCC for redevelopment, the Rose and Crown was rebuilt, and the 1950s version of the Rose and Crown pub can be seen on the street today:

Probably the most famous owners of the Rose and Crown were Queenie and Slim Watts. Born locally on the Isle of Dogs, Queenie was also a jazz singer. They ran two pubs, the Rose and Crown on Pennyfields and the Iron Bridge Tavern, at 447 East India Dock Road.

I cannot find the exact dates when Queenie Watts ran the Rose and Crown, various Internet posts about her refer to both the 1960s and 1970s, so it may have been across both decades.

Most newspaper reports about her and one of the pubs are from the 1960s, where, for example, the Stage on the 5th of November 1964 refer to “Queenie Watts of the Iron Bridge as the East Ends first lady”.

There are a number of videos of her singing and perhaps one of the best to give an impression of her pubs in the 1960s is this video, which looks a real rather than a staged event, by the way people look at the camera.

The Rose and Crown closed in the year 2000 and for a while was converted into a private house. Today, the ground floor is home to a Chinese restaurant.

The following photo is looking along Pennyfields, towards Poplar High Street. The south side of the street is on the right and in the late 19th century was described as the poorest side of the street, with cheap and crowded lodging houses, houses occupied by poor manual labourers, and brothels.

The reason why a photo of Pennyfields was included in the Wonderful London book was down to the reputation of Pennyfields and Limehouse Causeway as being the east London home of hundreds of Chinese seafarers and their families.

This was only for a relatively short period of time from the 1st World War to the 1930s, with the peak of the area’s reputation being in the 1920s – the same time as Wonderful London was published.

Pennyfields had always been multicultral, and checking census data and street directories, Jewish, Irish, Scandinavian and German names can be found.

In the 1910 street directory there was a Scandinavian Reading Room, and there were only two names which appear to be of Chinese origin: Wan Tsang, a Tobacconist at number 6, and Chang Ahon, an Interpreter at number 42.

The number would grow rapidly, with 182 Chinese men living in Pennyfields in 1918, and in the 1930s, around 5,000 were recorded as living in Pennyfields, Limehouse Causeway and the surrounding streets.

Moving into the area around Pennyfields was mainly down to the very close proximity of the docks (many were seamen), the availability of shops, restaurants etc. serving a Chinese customer base, and living in the same area as those of a similar origin – themes which have always influenced waves of east London immigration. Hostility from British sailors also prompted a clustering together by the Chinese seafaring community.

Pennyfields and Limehouse Causeway entered the public imagination as a place of mystery, opium dens, crime, brothels etc. In the 1920s, people from the wealthier parts of London would visit the area on a tour to see the mysterious Chinatown. East London opium dens have long featured in literature, film and TV series.

In reality, Pennyfields was much like any other east London street. It had a large Chinese population, but there were also many other nationalities as well as British working class.

The street was poor, housing and lodgings were crowded and in poor condition (again, much like many other east London streets). The street served a local economy, so to make money from the nearby docks there were pubs, brothels and lodging houses. The street had a mobile population as seamen from the docks arrived and departed.

Signage in the street added to its reputation, with Chinese names and written characters appearing on buildings – as seen on the resturant of H. Doe. Foon, but again much of this was short lived.

H. Doe Foon was on the corner of Pennyfields and West India Dock Road, and had a West India Dock address, being at number 57.

In the 1910 Post Office Directory, 57 West India Dock Road is listed a being occupied by Hutton and Co. Ship Chandlers. In the East London Observer, on the 10th of May 1930, 57 West India Dock Road was advertised as having the freehold for sale of a prominent corner shop and rooms. H. Doe Foon is listed in the 1920 street directory, so I suspect that it was the H. Doe Foon restaurant for nearly all of the 1920s.

But by being photographed and published in Wonderful London, H. Doe Foon has added to the street’s reputation.

The text with the photo in Wonderful London describes that within the street are “a score of shops selling chop suey, dried fish and vegetables, monster medicinal pills, tea, weird sweetmeats, and white preparation of palm”.

The text also describes crowded rooms with Chinamen playing “fan tan”, gambling, and the availability of drugs with a chalk cross on a door indicating that opium is available, and two crosses that cocaine can be purchased (perhaps like the Westferry Arms, Wonderful London also mentions that “it is virtually impossible for the police to obtain sufficient evidence to convict”).

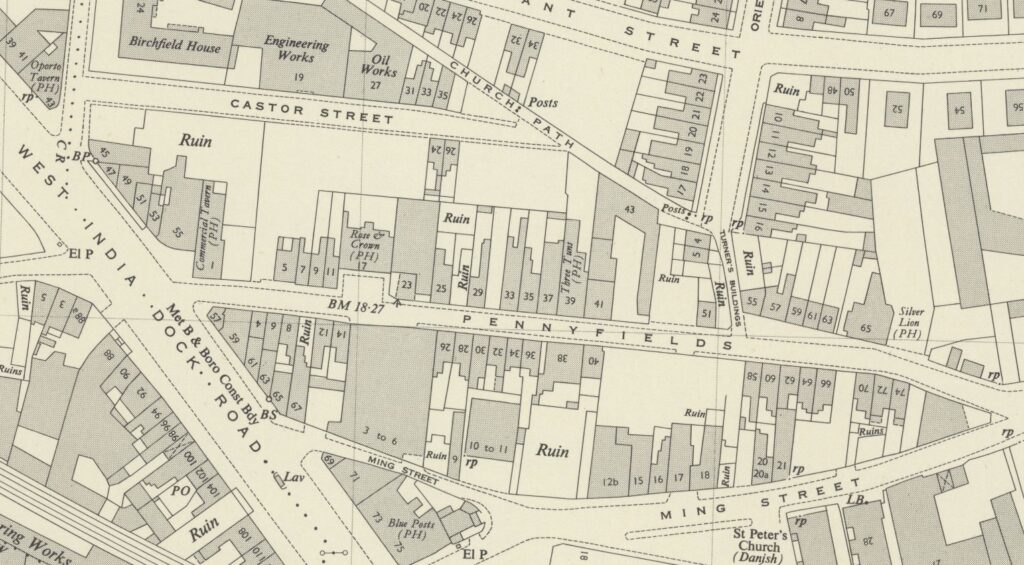

The 19th century buildings of Pennyfields lasted until the 1950s and 1960s, when they were finally demolished to make way for new LCC / GLC flats and housing. The following extract from the 1950 OS map shows that many buildings did survive wartime bombing, although they were in a very poor condition by this time (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

In the above map, the Rose and Crown is shown, so no longer a beer house, and to the right, at number 39, is the Three Tuns, one of the oldest pubs on the street. The first reference I can find to the pub is from 1826, when the name of the pub was used in a fraud where cheques were presented at various London breweries in an attempt to get the fake cheque cashed. Over £400 had been made this way before the person running the fraud was caught.

As with the rest of the street, the Three Tuns was demolished for post war redevelopment, which included Rosefield Gardens (a new street running north from Pennyfields) and the surrounding housing:

Much of the north eastern side of Pennyfields is now a park – Pennyfields Park, which again was created during the redevelopment of the area, the following photo shows one of the entrances to the park. the Three Tuns pub would have been just to the right, behind the recycling signage.

That a Pennyfields Park was created in the post war redevelopment of the area may be an accidental pointer to the origins of the name.

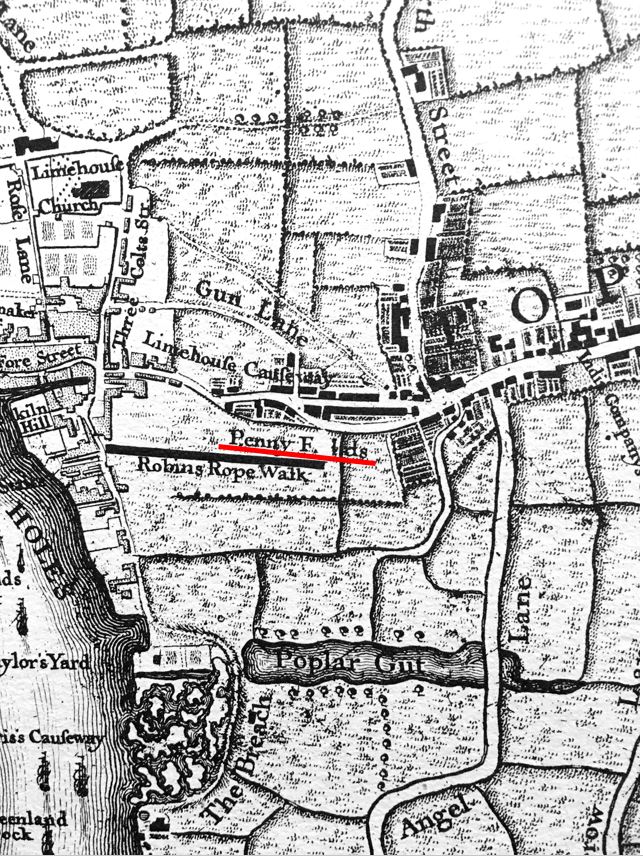

The meaning of the name is lost, however on Rocque’s 1746 map of London there is a reference to a Penny Fields, which seems to have been a 16 acre block of mainly undeveloped land (underlined in red in the following extract):

As well as being on Rocque’s 1746 map, there are mentions of the 16 acres of Penny Fields in 17th century land transactions, so the name does go back to at least the 1600s.

In the above map extract, Poplar High Street is on the right, and the street that will take the name Pennyfields is the straight street that connects Poplar High Street to Limehouse Causeway.

There is one final pub to track down, and this may well be the oldest on the street. To the right of the OS map of Pennyfields is a pub called the Silver Lion.

The first mention of the Silver Lion is from an advert for a property for sale, which gives us a description of the area before the dense housing that would come during the rest of the 19th century.

On the 21st of February 1815, the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser was advertising “the Leasehold premises, known as Ebenezer House, near the Silver Lion, Penny Fields, Poplar, comprising a substantial brick built dwelling house most commandingly situate at the end of Penny Fields, in the most preferable part of Poplar High Street , with a large plot of garden ground in the front, enclosed with a dwarf wall and palisade railings. The house contains four good bedrooms, two parlours, entrance passage, kitchen, pantry, wine cellars, and other conveniences”.

If you look at the Rocque map extract, there is a Robins Rope Walk, this appears to have been within the 16 acres of Penny Fields as in the same newspaper as the above advert, there is also for sale “a Leasehold estate, adjoining Mr. Burchfield’s rope-ground, Penny-Fields, Poplar”.

So Pennyfields started off as a 16 acres plot of land to the south of the street, and included a rope-ground where lengths of rope for ships was made.

The name then was used for a street connecting Poplar High Street and Limehouse Causeway.

Originally with a few larger houses with gardens, the street was densely built during the 19th century with houses and premises that catered to the nearby West India Docks.

At the end of the 19th century, and in the early decades of the 20th century, Pennyfields was at the centre of the Chinese population in east London.

The post-war decline of the docks, bomb damage, and the gradually decaying state of the housing within Pennyfields led to redevelopment by the LCC and then the GLC which demolished all the 19th century buildings, rebuilt the Rose and Crown, and lined the street with new flats.

And that is how we see the street today, however although the name dates back to at least the 17th century, I suspect Pennyfields will always be known for the Chinese influence on the street for a few decades in the early 20th century.