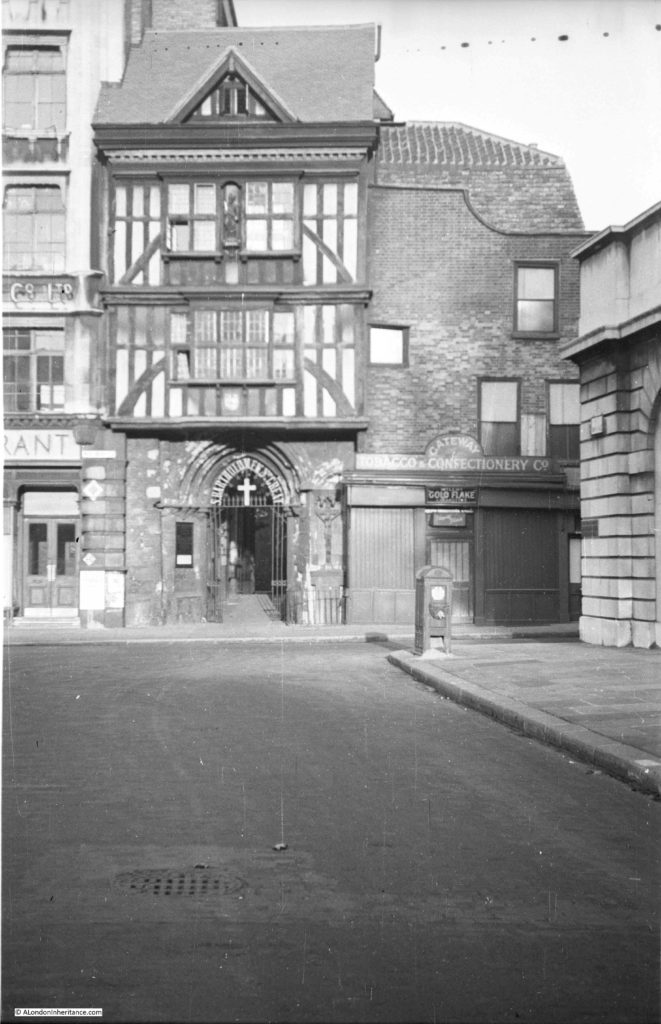

For this week’s post, I am still in West Smithfield after visiting St. Bartholomew last week, at the corner of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane. This is the photo that my father took of the Golden Boy, reputed to mark the location where the Great Fire of London finally burnt itself out.

This is my photo of the same location with the Golden Boy now mounted on the corner of the latest building on the site, rather than on the Cock Lane side as in my father’s photo.

Cock Lane is one of London’s old streets, the first reference being in the early 13th Century as Cockes Lane. It was the only street in medieval London licensed for prostitution. It was also the street where John Bunyan, the author of The Pilgrim’s Progress, died in 1688.

The two main theories as to the source of the name appear to be either reference to prostitution or cock-fighting. I suspect with a street of this age we will never know which is right.

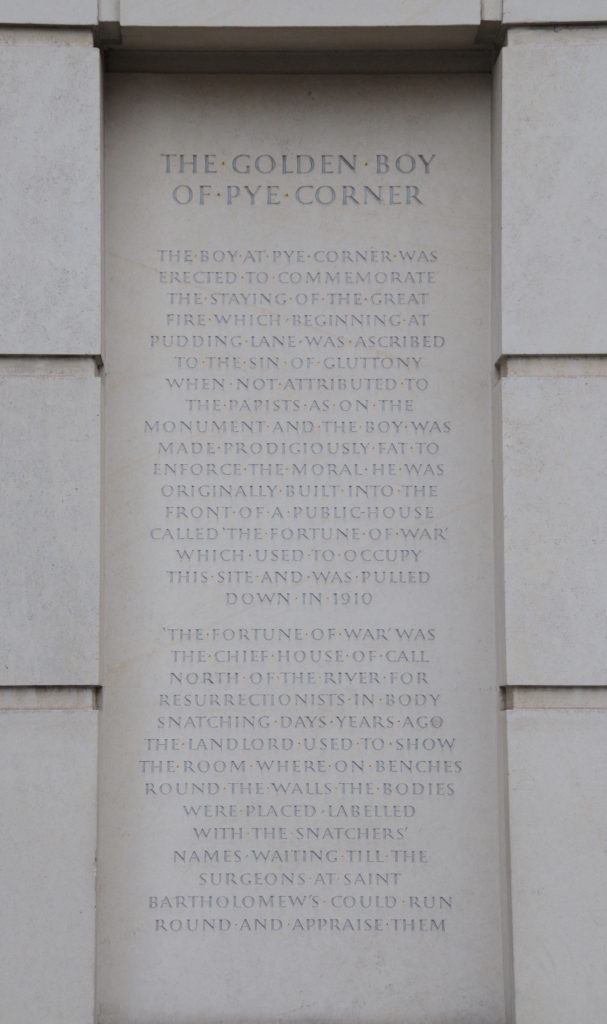

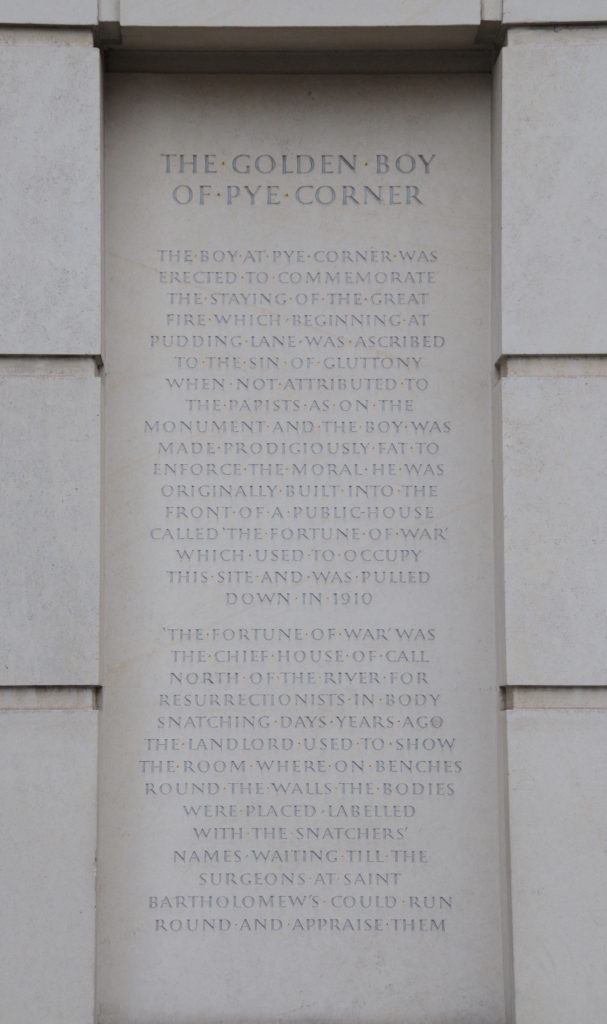

The association of the Golden Boy with the Fire of London was to attribute the cause of the fire to the sin of gluttony, rather than to a Catholic, popish plot which was the original scapegoat for the cause of the fire and inscribed on the Monument. I can find no original evidence confirming that the Golden Boy was put up for this purpose, or that the fire burnt itself out at this point.

On the base of the statue are the words Puckridge Fecit Hosier Lane, meaning Puckridge Made Me, with Hosier Lane being a street adjacent to Cock Lane.

The earliest reference I have found to Puckridge is in the book “Ancient Topography of London” by John Thomas Smith, first published in 1815:

“The figures that strike the bells at St. Dunstan’s each move an arm and its head. One of them lately received a new arm, from the chisel of Mr. Willian Puckridge of Hosier Lane, West Smithfield; who informed me, that he, his father, and his grandfather, who were all wood-carvers, and had lived on the same spot, have carved most of the Grapes, Tuns, Swans, Nags-heads, Bears, Bacchus’s, Bibles, Black Boys, Galens, &c. both for town and country, for these hundred years.

Mr. Puckridge also informs me, that the wooden figure of the naked boy, put up at Pye-corner, is certainly the original one, for that his grandfather first repaired it.”

So given that this was written in 1815 and records that the boy at Pye Corner was repaired by his grandfather, it must put the boy back to at least the middle of the 18th Century.

Below the Golden Boy today is a large plaque providing background to the statue and the building on which the boy was mounted for some years, the Fortune of War public house, and the role that this pub played in the trade in bodies between the resurrectionists who would snatch bodies from graves, and the surgeons who worked at the nearby St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

The earliest reference I have found attributing the statue of the Golden Boy to the Fire of London is in the 1790 edition of “Of London” by Thomas Pennant who writes:

“In Pudding-lane, at a very small distance from this church, begun the ever memorable calamity by fire, on the 2nd of September, 1666. In four days it consumed every part of this noble city within the walls, except what lies within a line drawn from the north part of Coleman-street, and just to the south-west of Leadnhall, and from thence to the Tower. Its ravages were also extended without the walls, to the west, as far as Fetter-lane, and the Temple. As it begun in Pudding-lane, it ended in Smithfield at Pye-corner; which might occasion the inscription with the figure of a boy, on a house in the last place, now almost erased, which attributes the fire of London to the sin of gluttony.”

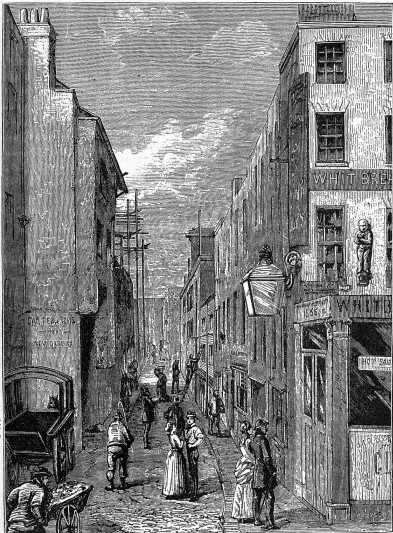

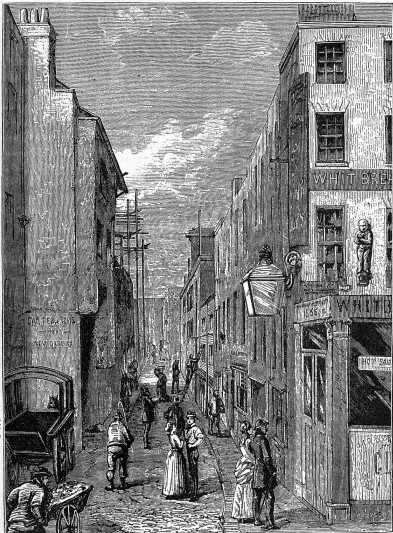

Old and New London by Walter Thornbury contains a drawing of Cock Lane with the pub on the corner with the statue of the Golden Boy.

Looking down Cock Lane today from the junction with Giltspur Street. The downwards slope of the street is indicative of the street heading down towards the location of the River Fleet. Cock Lane runs down to Snow Hill and then Farringdon Street and the Holborn Viaduct crossing.

It was under Holborn Viaduct and along Farringdon Street that the River Fleet once ran and the slope of many streets on either side provide a reminder of the long hidden river.

At the junction of Cock Lane and Snow Hill is this original front to the showroom of the business of John J. Royle of Manchester.

Royle was born in Manchester in 1850 and created a successful engineering business. His company made many of the products needed to make use of steam power, including radiators, water heaters and heat exchangers.

He was also the prolific inventor of a range of other products, one of which was the self pouring teapot. The teapot worked by using a pump that was operated by the lifting and lowering of the lid of the teapot. This action would pump tea out through the spout. It enabled a large quantity of tea to be available for a Victorian family and friends without the need to lift a heavy object filled with a hot liquid.

The door to the Royle showroom.

As well as the Golden Boy, Cock Lane is associated with another London legend, the Cock Lane Ghost which created a sensation across London and the country in 1762.

The ghost was not seen, only heard as a series of knocking and scratching, including responding to simple questions by answering one knock or two. Walter Thornbury tells the story of the ghost, and of some of the society and political figures who visited Cock Lane in Old and New London:

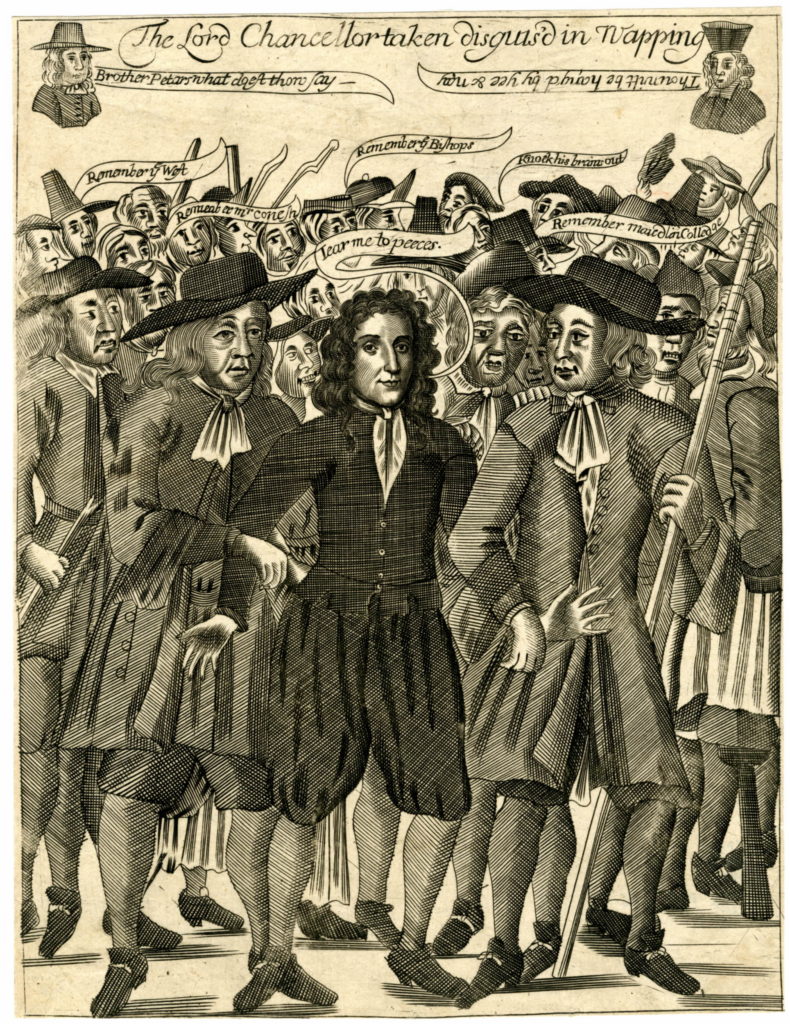

“Cock Lane, an obscure turning between Newgate Street and West Smithfield, was, in 1762, the scene of a great imposture. The ghost supposed to have been heard rapping there in reply to questions, singularly resembled the familiar spirits of our modern mediums.

Parsons, the officiating clerk of St. Seplulchre’s, observing, at early prayer, a genteel couple standing in the aisle, and ordering them into a pew. On the service ending, the gentleman stopped to thank Parsons, and to ask him if he knew of a lodging in the neighbourhood.

Parsons at once offered rooms in his own house, in Cock Lane, and they were accepted. The gentleman proved to be a widower of family from Norfolk, and the lady the sister of his deceased wife., with whom he privately lived, unable, from the severity of the ancient canon law, to marry her as they both wished. In his absence in the country, the lady, who went by the name of Miss Fanny, had Parson’s daughter, a little girl of about eleven years of age, to sleep with her. In the night the lady and the child were disturbed by extraordinary noises, which were at first attributed to a neighbouring shoemaker. Neighbours were called in to hear the sounds, which continued till the gentleman and lady removed to Clerkenwell, where the lady soon after died of smallpox.

In January of the next year, according to Parson’s, who, from a spirit of revenge against his late lodger, organised the whole fraud, the spiritualistic knockings and scratchings recommenced. The child, from under whose bedstead these supposed supernatural sounds emanated, pretended to have fits, and Parsons began to interrogate the ghost, and was answered with affirmative or negative knocks. the ghost, under cross examination declared that it was the deceased lady lodger, who, according to Parsons, had been poisoned by a glass of purl, which had contained arsenic. Thousands of persons, of all ranks and stations, now crowded to Cock Lane, to hear the ghost and the most ludicrous scenes tool place with these poor gulls.”

To precis Thornbury’s account, the story of the ghost is that William Kent was living with his wife’s sister Fanny and posing as husband and wife at the home in Cock Lane of Richard Parsons. This was in 1749, a few years before the appearance of the ghost. Whilst at Cock Lane, Parson’s was apparently in debt to Kent, and whilst Kent was away, Fanny would share a room with Parsons daughter, Elizabeth.

When Kent returned, they moved to Clerkenwell where Fanny later died of smallpox. When the ghostly scratching and knocking started, Parsons claimed that it was the ghost of Fanny who had returned as she had been poisoned by arsenic rather than dying of smallpox.

Parsons was making money out of the ghost by charging for admission to his home to experience the phenomena. Walter Thornbury also records the visit of Horace Walpole and the Duke of York to Cock Lane:

“Even Horace Walpole was magnetically drawn to the clerk’s house in Cock Lane. The clever scribble writes to Sir Horace Mann, January 29, 1762: ‘I am ashamed to tell you that we are again dipped into an egregious scene of folly. The reigning fashion is a ghost – a ghost, that would not pass muster in the paltriest convent in the Apennines. It only knocks and scratches; does not pretend to appear or to speak. The clergy give it their benediction; and all the world, whether believers or infidels, go to hear it. I, in which number you may guess go tomorrow; for it is as much the mode to visit the ghost as the Prince of Mickleburg, who is just arrived. I have not seen him yet, though I have left my name for him.”

Walpole continues “I went to hear it, for it is not an apparition, but an audition. We set out from the opera, changed our clothes at Northumberland House, the Duke of York, Lady Northumberland, Mary Coke, Lord Hertford, and I, all in one hackney-coach, and drove to the spot. It rained torrents; yet the lane was full of mob, and the house so full we could not get in. At last they discovered it was the Duke of York, and the company squeezed themselves into one another’s pockets to make room for us. the house, which is borrowed, and to which the ghost has adjourned, is wretchedly small and miserable.

When we opened the chamber, in which were fifty people with no light, but one tallow candle at the end, we tumbled over the bed of the child to whom the ghost comes, and whom they are murdering by inches in such insufferable heat and stench. At the top of the room are ropes to dry clothes. I asked if we were to have rope-dancing between acts. We heard nothing. they told us (as they would at a puppet-show) that it would not come that night till seven in the morning, that is, when there are only ‘prentices and old women. We stayed, however, till half an hour after one. The Methodists have promised them contributions. Provisions are sent in like forage, and all the taverns and ale-houses in the neighbourhood make fortunes.”

The Cock Lane ghost made the front pages of newspapers across the country, with accounts of the question and answer sessions held with the ghost. Pamphlets were issued along with drawings that described the scene, one of which is shown below and titled “English Credulity or the Invisible Ghost”

The child is shown in bed whilst an image of the ghost with a hammer to make the knocking sounds floats above. A man is checking under the bed whilst another stands adjacent to the bed, shielded from the child by a curtain, and asks the ghost to knock three times if he is holding up a gold watch.

The woman to the right of the bed cries “I shall never have any rest again” whilst the man seated at the table is concerned by imploring “Brother don’t disturb it”.

The ghost was eventually exposed as a fraud. During the question and answer sessions with the ghost, the ghost said that it would knock on the coffin of Fanny in St. John’s Clerkenwell, but when the committee formed to investigate the ghost visited the crypt and coffin of Fanny, nothing happened.

The child Elizabeth was then taken to another house where she was watched closely and a piece of wood was found concealed within her clothing which she had been using to make the scratching and knocking sounds.

Parson and his wife were arrested and charged with conspiracy to take away the life of Kent by alleging that Kent had murdered Fanny. They were found guilty and Parson’s was placed in the pillory in addition to a two year jail sentence, although the local population still appears to have supported him as rather than throw stuff at him whilst in the pillory, they made a collection to help Parson’s through his time in jail.

I cannot find any record of what happened to Parson’s daughter, Elizabeth.

Such was the fame of the Cock Lane ghost that the actor David Garrick wrote an interlude called “The Farmer’s Return From London” which included the ghost and was performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1762.

The Interlude is set in the farmer’s kitchen with the actors playing the Farmer (played by David Garrick) with his wife (Mrs. Bradshaw), and his children, Sally (Miss Heath), Dick (Master Pope) and Ralph (Master Cape).

The farmer has just returned from a trip to London and is telling his family of his experiences and his view of London. He tells them of the streets within streets, the houses on houses and the streets paved with heads. Sally asks if he saw any plays and shows and he tells them of the gold, painting and music, the curs’ing and prattling and of the fine cloths.

The farmer saves the best to last when he tells his family that he has sat up with a ghost. The Interlude then continues:

Farmer: Odzooks! thou’t as bad as thy betters above. With her nails and her knuckles she answered so nice. For Yes she knocked once, and for No she knocked twice. I asked her one thing –

Wife: What thing?

Farmer: If yo’ Dame, was true.

Wife: And the poor soul knocked one.

Farmer: By the zounds, it was two!

Wife: (cries) I’ll not be abused, John

Farmer: Come, prithee, no crying, the ghost among friends, was much given to lying.

Wife: I’ll tear out her eyes –

Farmer: I thought, Dame, of matching your nails against hers, for your both good at scratching. They may talk of the country, but I say, in town, their throats are much wider to swallow things down. I’ll uphold, in a week – by my trough I don’t joke – that our little Sal shall fright all the town folk. Come, get me my supper. But first let me peep, at the rest of my children – my calves and my sheep.

Wife: Ah, John!

Farmer: Nay, cheer up. Let not the ghosts trouble thee, Bridget, look in thy glass, and there thou ,ay’s see, I defy mortal man to make cuckold o’ me.

The advertisement for the Interlude explains that Garrick’s friend Hogarth had drawn the scene for the printed version of the Interlude:

“Notwithstanding the favourable reception he has met with, the author would not have printed it, had not his friend, Mr. Hogarth, flattered him most agreeably by thinking The Farmer and his Family not unworthy of a sketch by pencil. To him, therefore, this trifle, which has so much honoured is inscribed, as a faint testimony of the sincere esteem which the writer bears him, both as a man and an artist.”

Hogarth’s drawing is shown below. The farmer is in his kitchen, telling the family of his experiences in London and of the Cock Lane Ghost. The wife in shock is pouring the farmer’s beer on the floor rather than in his cup.

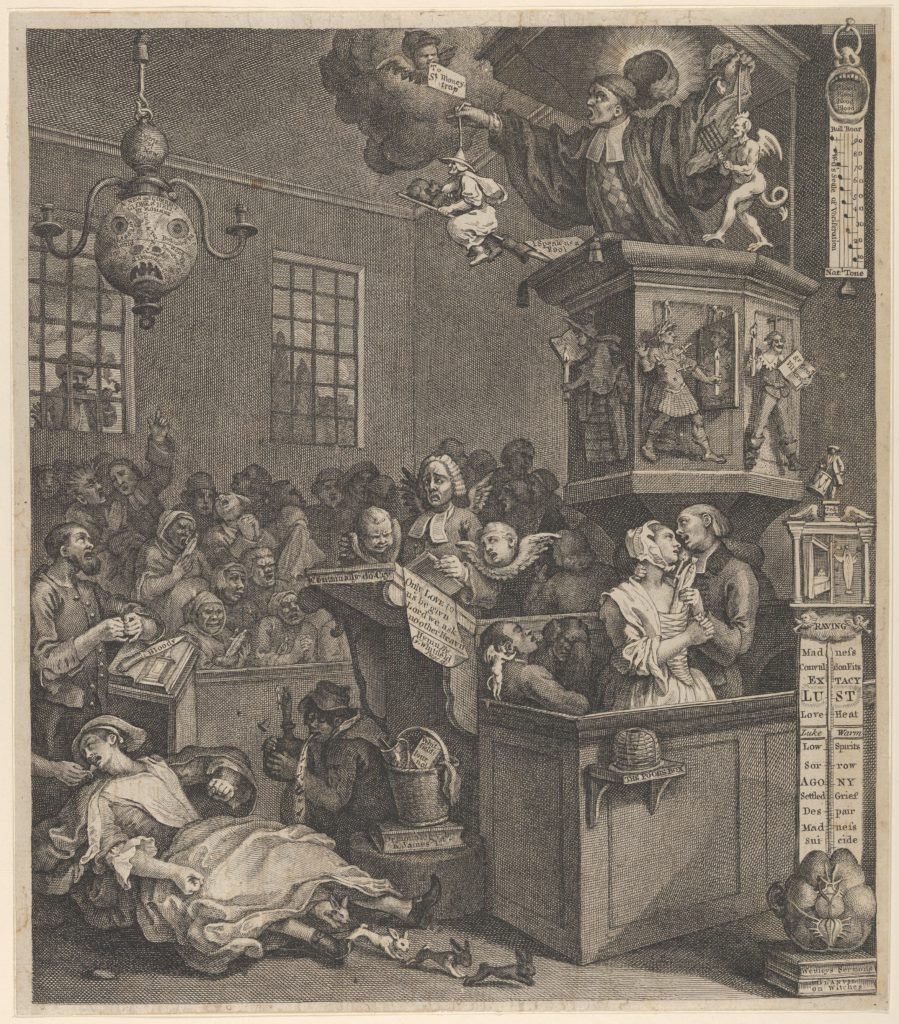

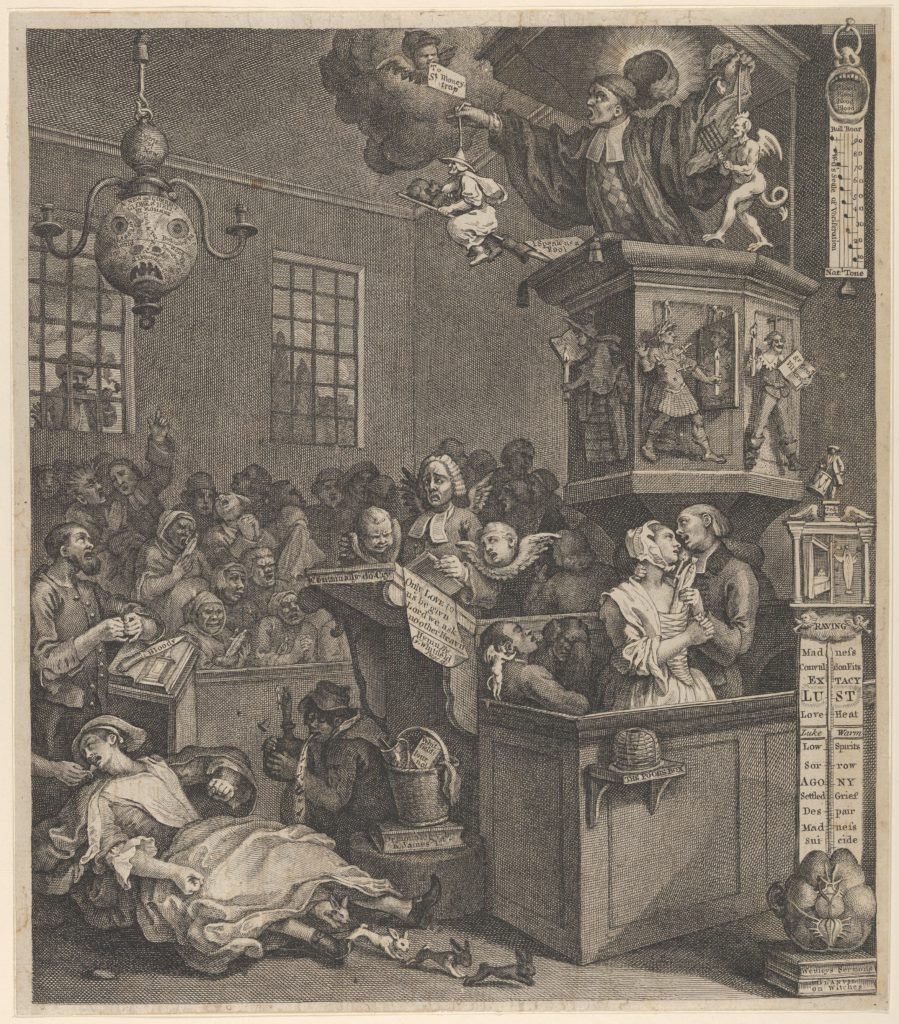

Hogarth also included references to the Cock Lane ghost in two of his other drawings. The first is called “Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism”.

Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism is an updated version of Hogarth’s Enthusiasm Delineated which was an attack on the upsurge in Methodism across London in the mid 18th Century. This began with the opening on Tottenham Court Road of a Methodist Tabernacle in 1756 and rumours that the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Secker also had Methodist sympathies.

Hogarth was urged not to publish Enthusiasm Delineated as it could have been seen as an attack on religion in general, not just on Methodism. He changed the drawing by replacing the religious images with images from the occult and superstition and it became Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism.

The Cock Lane ghost reference is on the large thermometer of madness on the lower right side of the print. In the panel at the top of the thermometer is an image of the child in bed with the Cock Lane ghost hovering to the right. Hogarth could also keep some aspects of his original aim with the drawing as Parsons, who was blamed for the fraud, was also a Methodist.

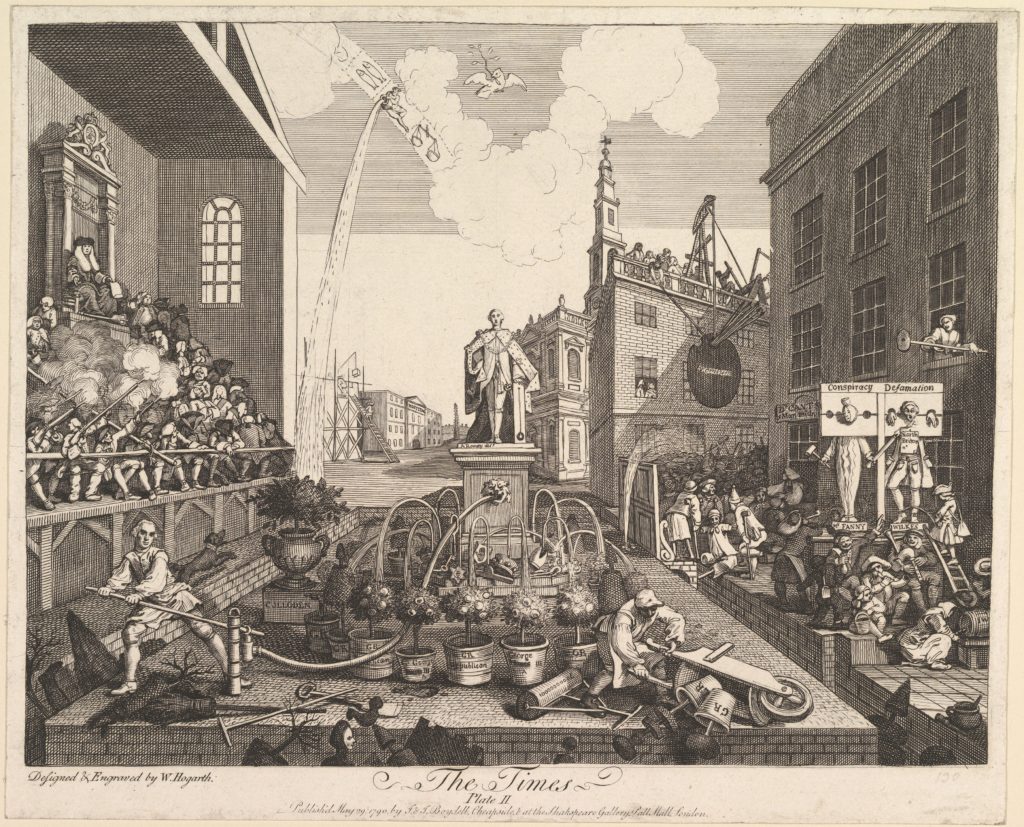

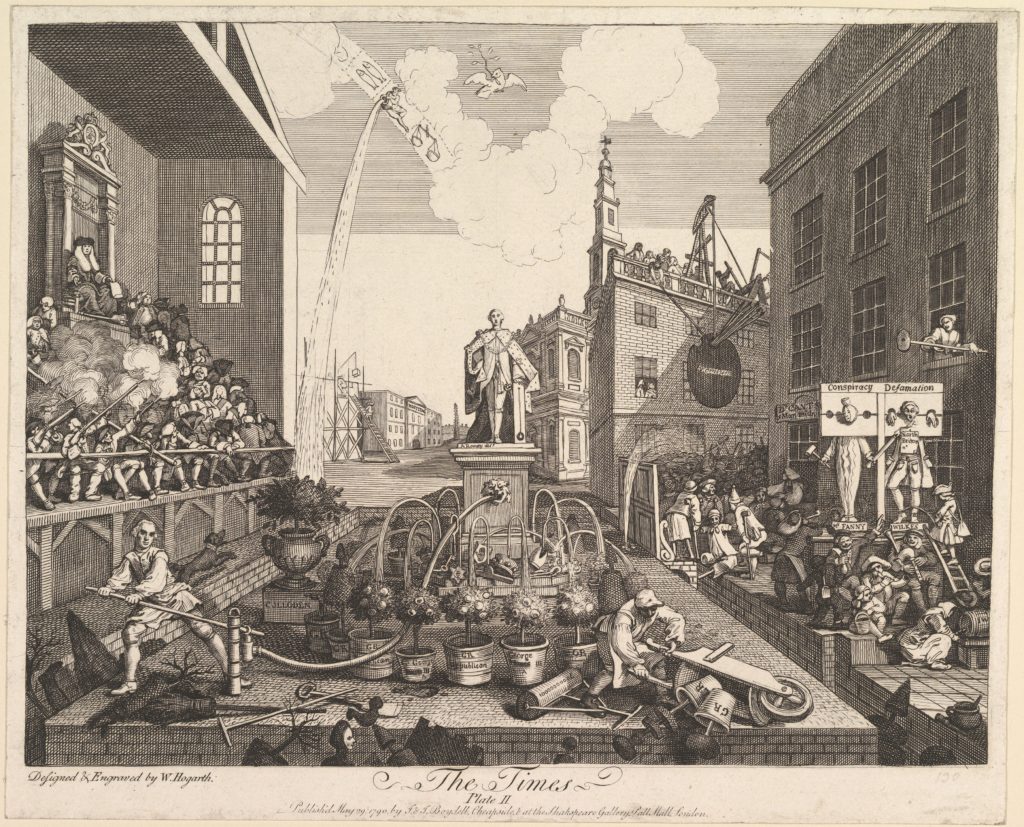

The second is plate 2 from Hogarth’s series of two prints titled “The Times”.

The Times was one of Hogarth’s most political series of prints. The early 1760s were a time of great political upheaval and rumour. The Seven Years war was coming to an end and negotiations were beginning on how to end the war, ending in the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

The first plate of The Times showed London in a state of chaos and fire, the result of the seven years war with the fires of the war still being fanned by William Pitt.

The second plate, as shown above, shows a much calmer scene with the new King, George III on a statue above a fountain watering bushes placed around the fountain. The stand on the left is packed with member of the House of Lords and the Commons, half are fast asleep and the rest are firing on the dove of peace.

On the right of the print is a pillory. John Wilkes is on the right with a copy of the publication he was involved in “The North Briton”, a satirical, supposed patriotic publication that attacked the Scots (mainly due to George III appointing the Scottish nobleman Lord Bute as Prime Minster who ended the years of Whig rule and the Seven Year War).

On the left of the pillory is the Cock Lane ghost holding a candle in the right hand and hammer in the left with the words Ms. Fanny at the base of the pillory.

I cannot think of another of example of where a haunting has been included in this type of print which is making so many statements on the politics of the day.

I suspect that most people walking past Cock Lane today, only stop to view and read about the Golden Boy, however it is strange to think of the mobs and visitors to the knocking and scratching ghost in this now quiet side street in 1762.

alondoninheritance.com