Last weekend was the brilliant Open House weekend when what seemed like hundreds of buildings around London opened their doors.

I had very limited time over the weekend, just a few hours on Sunday so only time to visit two locations, but ones I have wanted to see for a long time, so for this week’s post a quick visit to the Chrisp Street Market Clock Tower and St. Pancras Chambers.

Chrisp Street Market

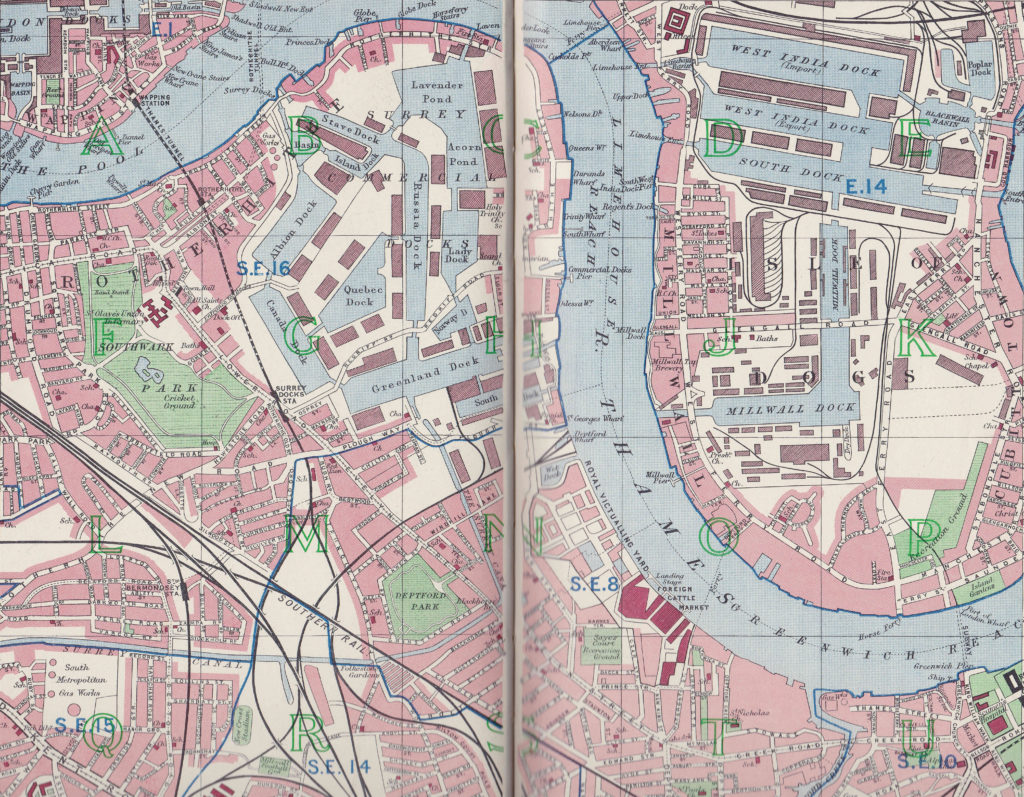

Chrisp Street Market was part of the Lansbury Estate development in Poplar and featured in the Festival of Britain Exhibition of Architecture. I covered this in a post back in July when I went for a walk around the estate with a copy of the original Exhibition Guide.

The Clock Tower at the corner of the market was built as part of the Lansbury development to serve a number of purposes. It would provide a feature for the market area, a viewing gallery over the new estate, and provide a landmark at the far end of Grundy Street with the new church at the opposite end.

The viewing platform on the Clock Tower was closed many years ago and now there is only occasional access, one of which was during this years Open House event.

Access to the viewing platform is via one side of a pair of interlocking reinforced concrete staircases. This design was to ensure that walking up was via one staircase and down was via the other so walking up you would not meet people coming down on the same staircase.

At the top of the Clock Tower, showing the two entrances to the staircases – only one was in use today.

At the top of the tower there is a fading wooden plaque. This is probably not as old as it looks. I believe this is from about 2014, although it looks much older and based on the text it is probably from the Chrisp Street on Air Project.

The text on the left of the plaque reads:

Neighbourhood 9

The nine locations of the field recordings series observing the Lansbury Estate and the people that live and work around Chrisp Street Market. Each broadcast centred on a single location uncovering the daily workings of each site and posing questions for its possible future.

No. 1 Lansbury Amateur Boxing Club

No. 2 Queen Victoria Seamen’s Rest

No.3 The Market Square

No. 4 Jp’s Cafe

No. 5 The Spotlight

No. 6 The Festival Bar

No. 7 New Festival Quarter

No. 8 Gladstone Tower

No. 9 The Clocktower

Neighbourhood 9 refers to the Lansbury Estate being the ninth development neighbourhood in Poplar after the last war. The nine locations are individual locations around the Lansbury Estate that each had their own recording made during the Chrisp Street on Air project and tell a story of the place in question with local people talking about their experiences and history of the area.

These recordings are really worth a listen and can be found as podcasts on iTunes at this link or via Audioboom here.

View along the viewing gallery. All Saints DLR station in the distance.

The Clock Tower was designed by Fredrick Gibberd and would have originally towered above the market, however later building between the market and the East India Dock Road has tended to overshadow the Clock Tower. It does though provide good views in a number of directions including this view looking towards the City. The Shard is in the centre of the view.

View from the top of the Clock Tower towards Erno Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower:

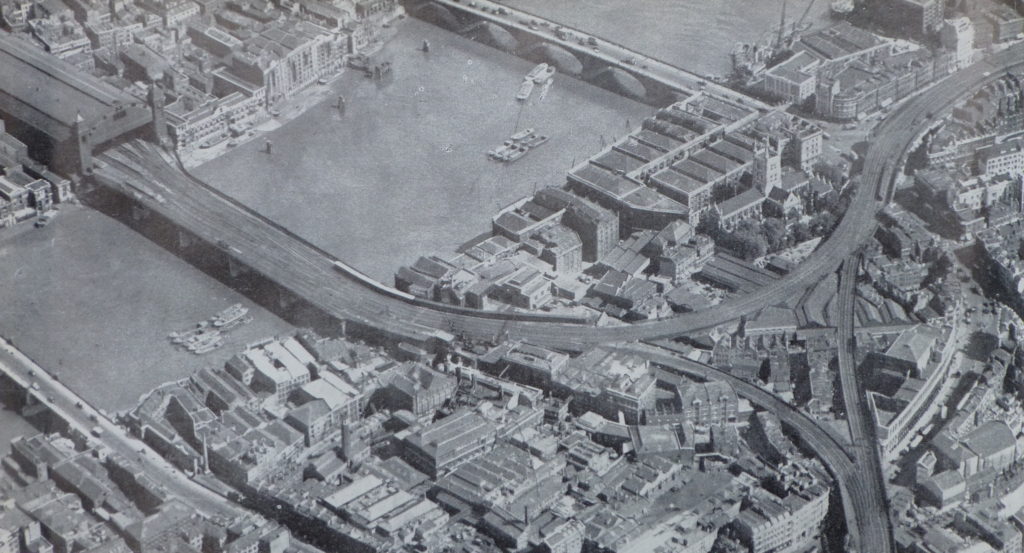

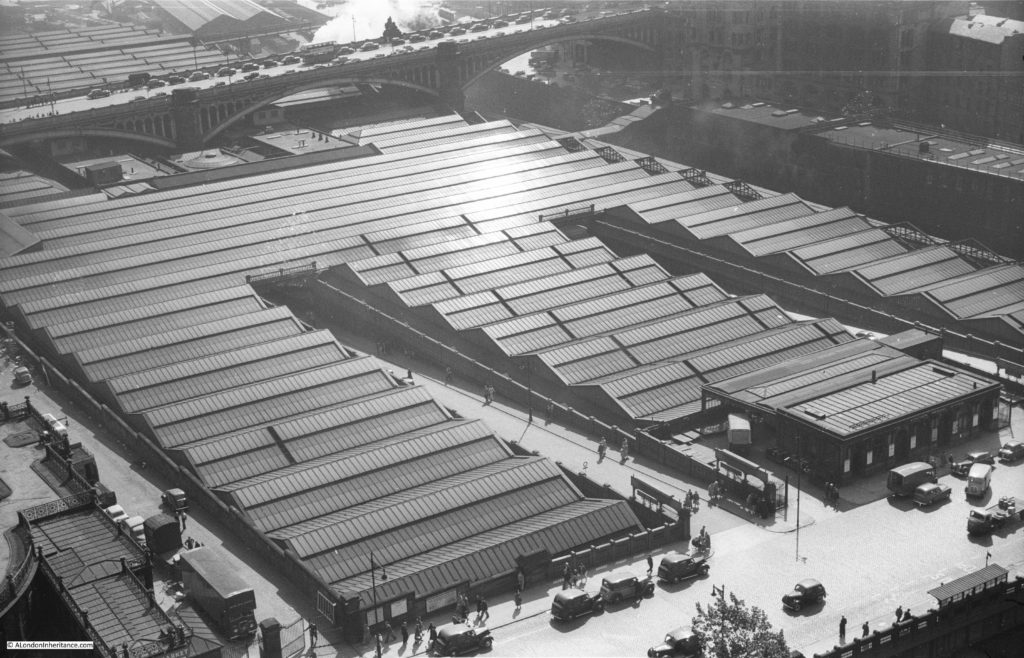

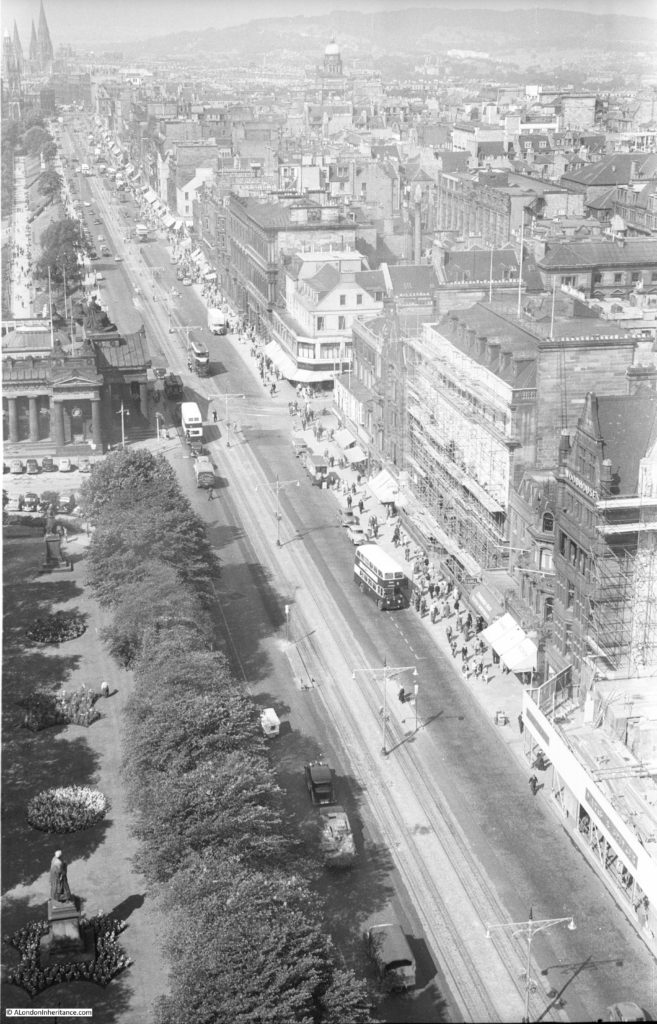

When built, this is the view that the visitor would have seen of the Lansbury Estate. The Chrisp Street market with the recent covered market area is in the lower half of the photo. The original buildings surround the market (again, see my post on the Lansbury Exhibition of Architecture for details of these buildings). To the left, Grundy Street can be seen running up to the church. Standing in the centre of Grundy Street gives an idea of the intention of the architects – the church and Clock Tower appear to anchor each end of the street. Religion at one end, shops, market traders and pubs at the other.

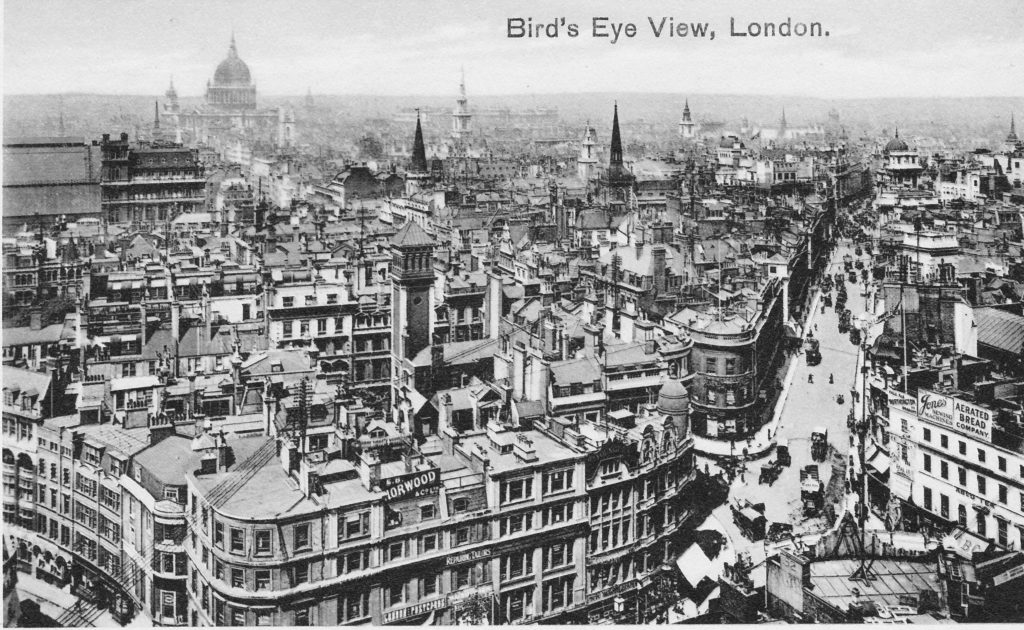

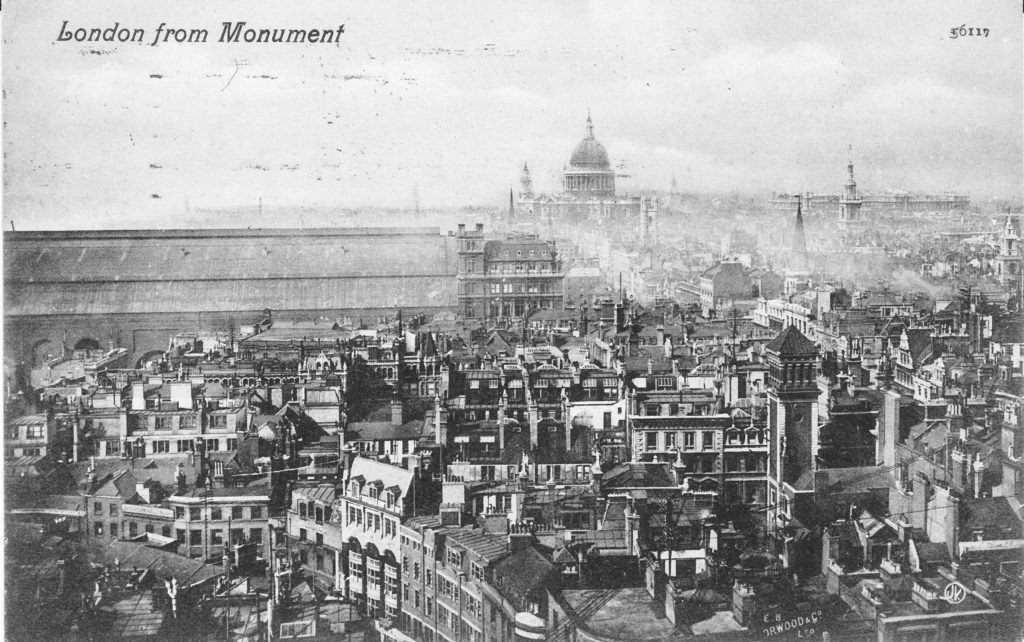

Continuing the theme of my recent posts on views from above London, it was interesting to see that St. Paul’s Cathedral is just visible to the left of the Cheesegrater building from the top of the Clock Tower.

View towards Stratford with part of the ArcelorMittal Orbit just visible in the centre of the horizon.

The Chrisp Street Market Clock Tower is starting to show its age. The height is very modest so it does not have the same views as other London viewing galleries, however as a symbol of the intentions of those behind the Lansbury Estate to create an integrated estate with housing and facilities for those who lived in the East End, it is perfect.

St. Pancras Chambers

St. Pancras Chambers was the name of the Open House tour inside parts of the original St. Pancras hotel and station buildings. The tour provided a quick look at the Grand Staircase, the corridors and staircases along the length of the building and the rooms at the top of the clock tower. The majority of the main building is now a hotel and the rooms in the Clock Tower are private apartments.

The building was designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and built between 1868 -76 and opened as the Midland Grand Hotel. Both the exterior and interior of the hotel was built to impress, to demonstrate the strength and magnificence of the Midland Railway Company in the new age of the railway. Built in the Victorian Gothic Revival style, using materials sourced mainly from across the midlands, the style of the building is very similar to Scott’s earlier work with the Albert Memorial.

Despite the apparent extravagance, costs were tight and some features were not included in the final build. Look to either side of the top of the entrance archway in the photo below. There is a space on either side of the top of the arch for a statue. There are a number of these empty positions across the buildings. Although planned, they were not included due to cost.

View of the Clock Tower, the rooms we would climb to are just below the clock.

The first stop on the tour was at the base of the Grand Staircase. This has been fully renovated as part of the renovation of the whole building and now provides a view of what it must have looked like when the building opened.

Floor tiles at the base of the staircase:

Looking up the staircase. The restoration of the Gothic Revival style of the staircase comes together through the floor tiles, carpets, wallpaper, lighting and the architecture of the windows and staircase.

Entrance to the staircase:

Corridors running from the Grand Staircase.

As well as the Grand Staircase there are a number of other staircases along the length of the building with different architectural styles:

Rooms at the end of one corridor were apparently used as Board Rooms for the Midland Railway Company. The decoration along this corridor is rather more ornate than the rest of the hotel corridors.

Walking up the stairs provides intriguing views of the station, including the following view at the rear of the station clock.

Along some of the corridors are these small doors above the larger doors for the hotel rooms. Apparently the smaller doors provided access to sleeping areas for the hotel staff.

In the clock tower.

Some interesting views from the clock tower. This one looking along Euston Road towards Pentonville Road with part of Kings Cross station on the left.

Looking south from the clock tower with the Shard in the distance.

Looking down one of the main stairwells:

As the majority of the building is now either the hotel or private apartments, the tour was limited, however it did cover the main features of the building and provided a welcome insight into this wonderful building from the time when rail was the future of transport.

Despite the very ornate architecture, the facilities in the original hotel were rather basic with a limited number of shared bathroom facilities, no lifts etc. The hotel did start to decline in the early years of the 20th century and closed in 1935, then being used as offices for the LM&S railway company.

Wartime damage, changes in transport from rail to road and a general decline put the station at risk in the 1960s but a campaign by people including Niklaus Pevsner and poet John Betjeman saved the hotel and station buildings and the arrival of the high-speed trains to Europe via the Channel Tunnel along with growing national rail use led to the redevelopment and restoration of the station and hotel which both now look spectacular.

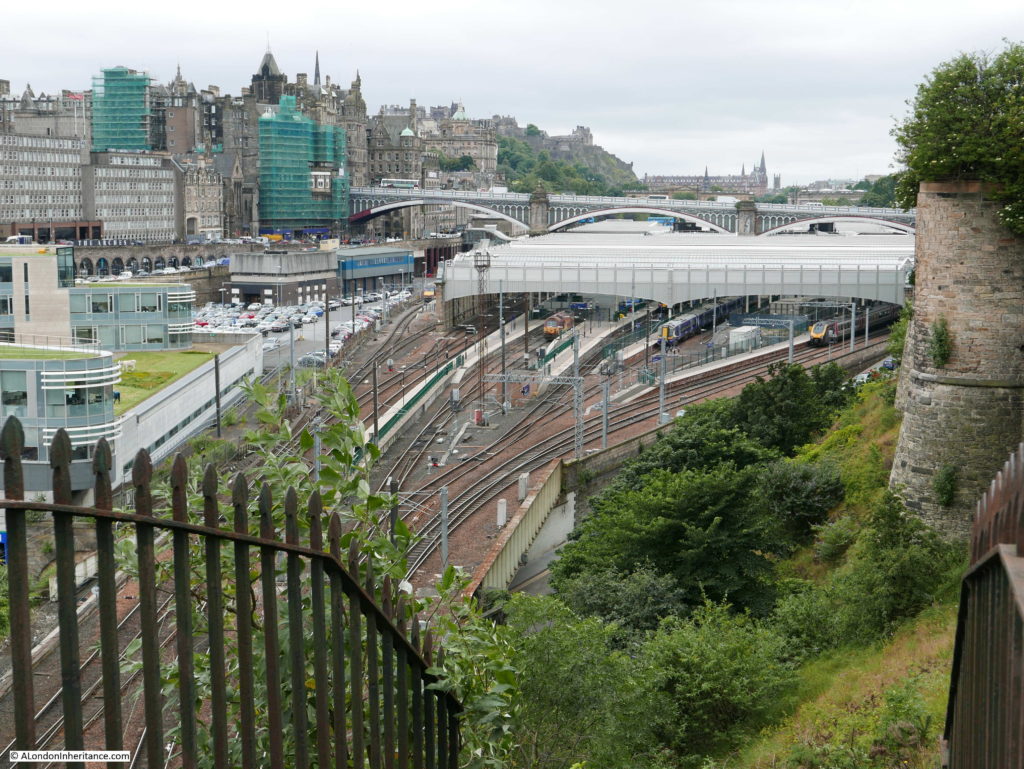

After the tour I walked to the station area. Here is the front of the clock that was visible from behind in the above photos.

The station roof.

The hotel and station buildings are impressive on both the large and small-scale.

Viewing from a distance you can see the whole sweep of the hotel, or the length of the roof however there are so many small architectural features across the building including these ornate carvings at the top of pillars in one of the entrances.

It was an all too brief visit to these two very different locations. Open House is a fantastic weekend of events which seems to be growing in scope every year. Hopefully I will have more time next year to visit more of the diverse range of locations available.