As with my Roupell Street post a couple of weeks ago, for this week’s post, a mid 1980s hairdressers is the reason why I am revisiting Carter Lane in the City of London. Initially to find the location of the Gentlemen’s Hairdressing Salon and Nichola’s Hair Designs of St Paul’s, but then to explore a very historic street, alleys, and two houses that have their origins back in the 17th century.

But first, here is the hairdressers on the corner of Carter Lane and St Andrews Hill, photographed in 1986:

The same place in July 2021:

The hairdressers are no more, and the latest occupier of the site, L’Express City, part of the L’Express chain of restaurants / coffee shops, has since closed. Possibly one of the casualties of the lack of customers in the City since the start of the pandemic.

The above two photos are on the corner of Carter Lane and St Andrews Hill. Carter Lane is an old street, but today is much longer than in previous centuries.

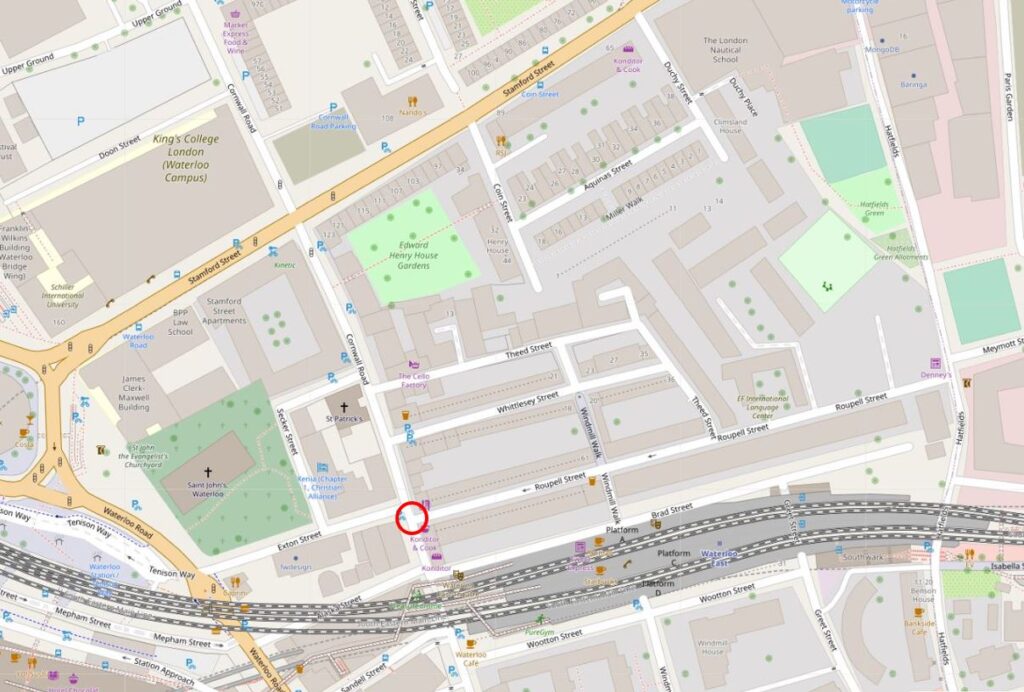

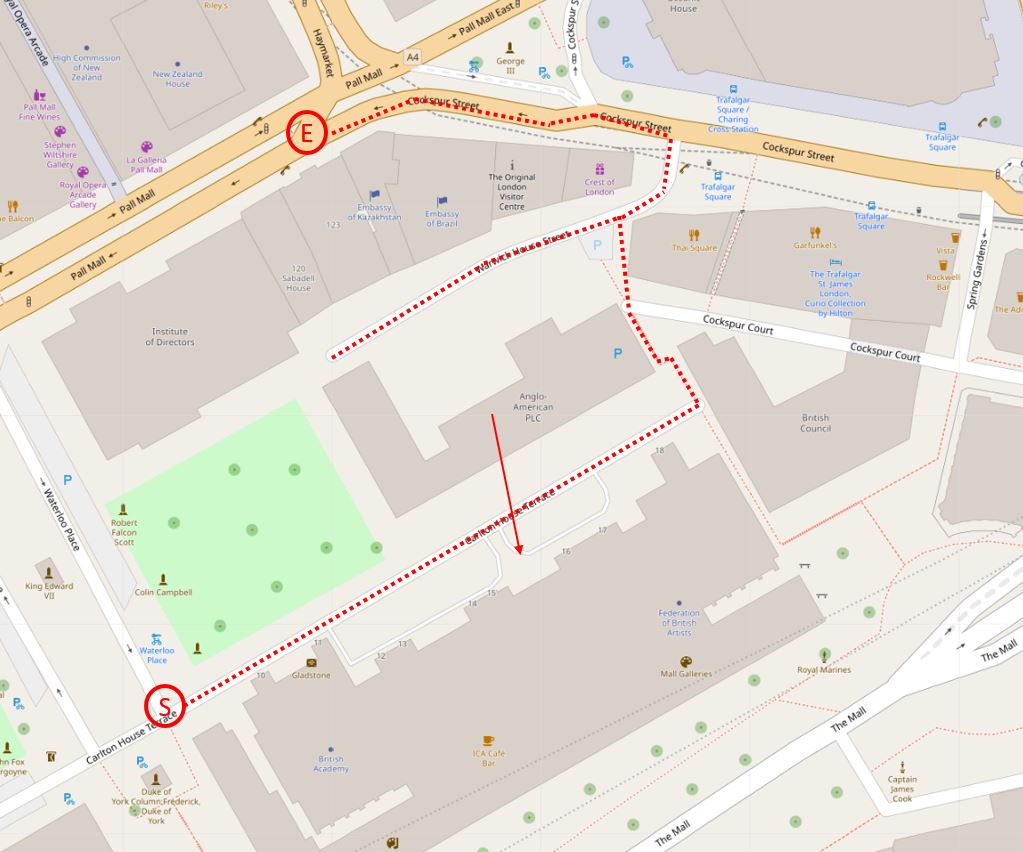

In the following map, St Paul’s Cathedral is the large building in the upper centre. Saint Paul’s Church Yard is the street immediately to the south of the cathedral. Keep going south, and the next street you will come to is Carter Lane (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

As can be seen in the above map, Carter Lane is a relatively long street. It has a central section in white, and the two outer sections are in grey. As we walk along the street, the relevance of the different colouring of the street will become clear.

In the above map, the eastern section to the right has green space between Carter Lane and the cathedral. This space is today the location of the City of London Visitor Centre, and an expanse of gardens, however this was once a densely built area.

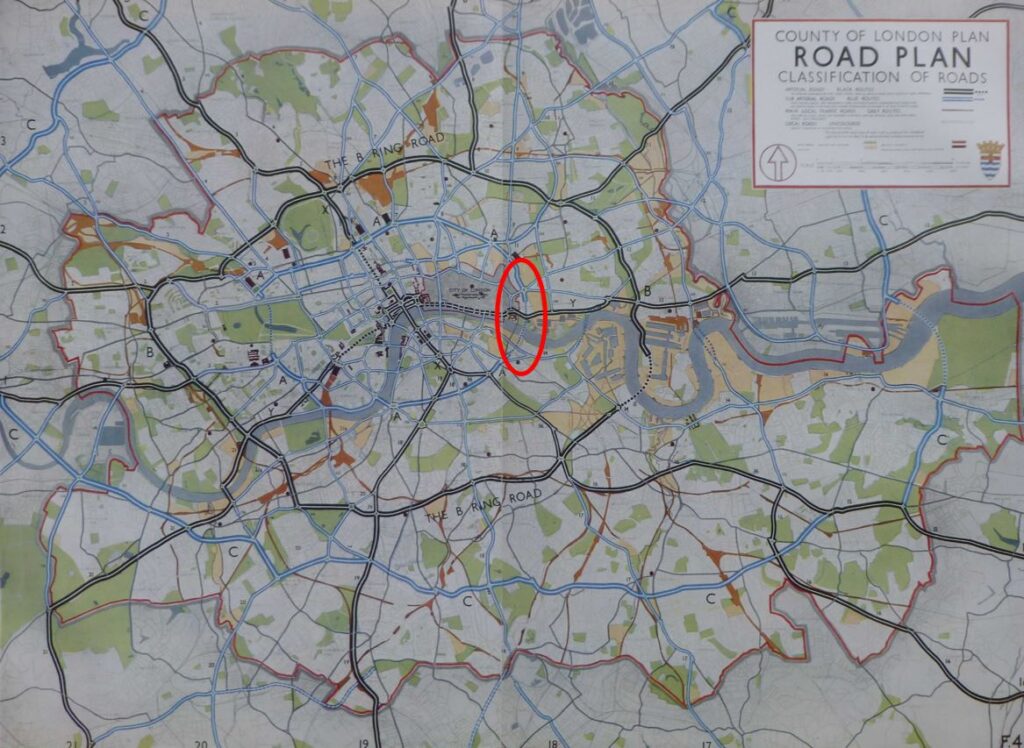

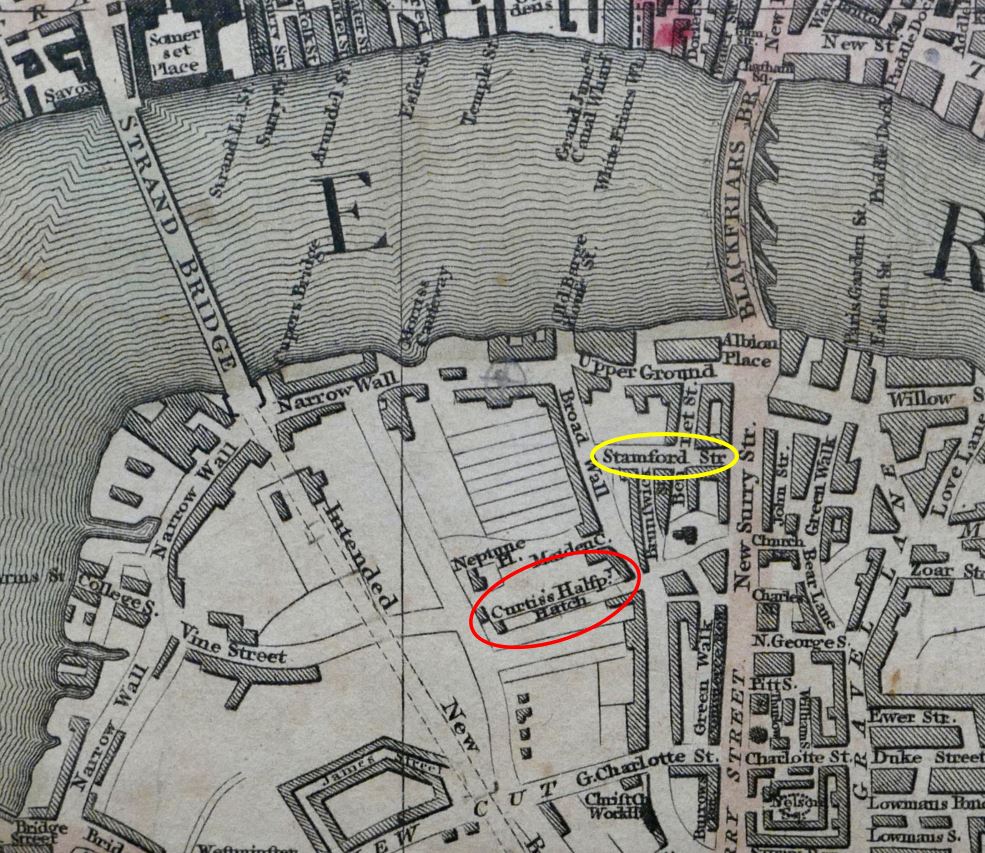

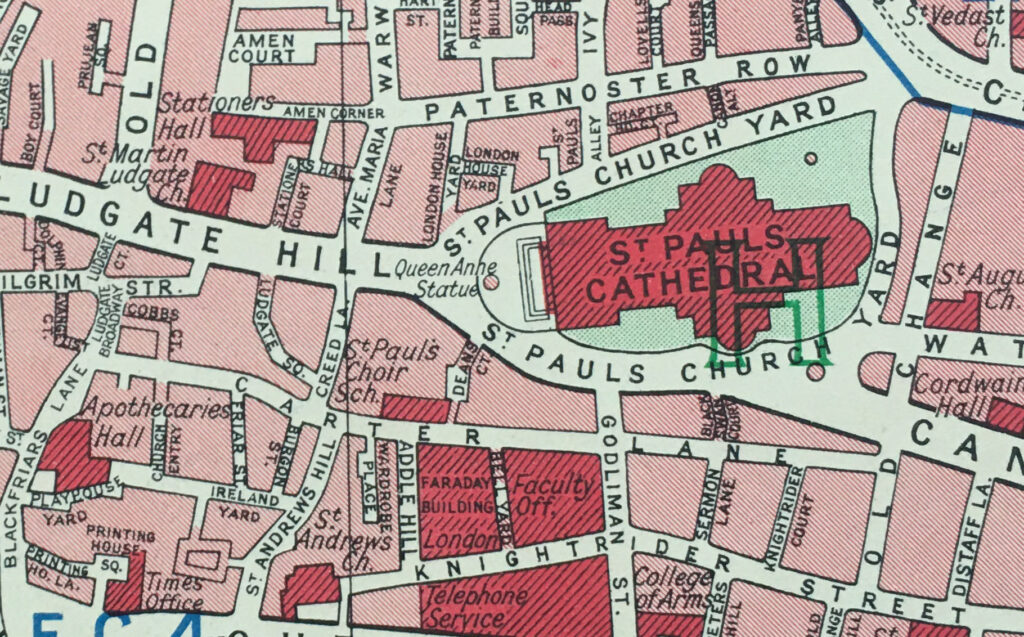

The following map is from the 1940 edition of Bartholomew’s Reference Atlas of Greater London.

Here we can see Carter Lane running from Blackfriars Lane in the west, to Old Change in the east. The area above the right section of the street, above the word “Lane”, now the site of gardens and visitor centre was then built up, with Black Swan Court running between Carter Lane and St Paul’s Church Yard.

There are a couple of key buildings highlighted in dark red in the above map, which I will come to later in the post.

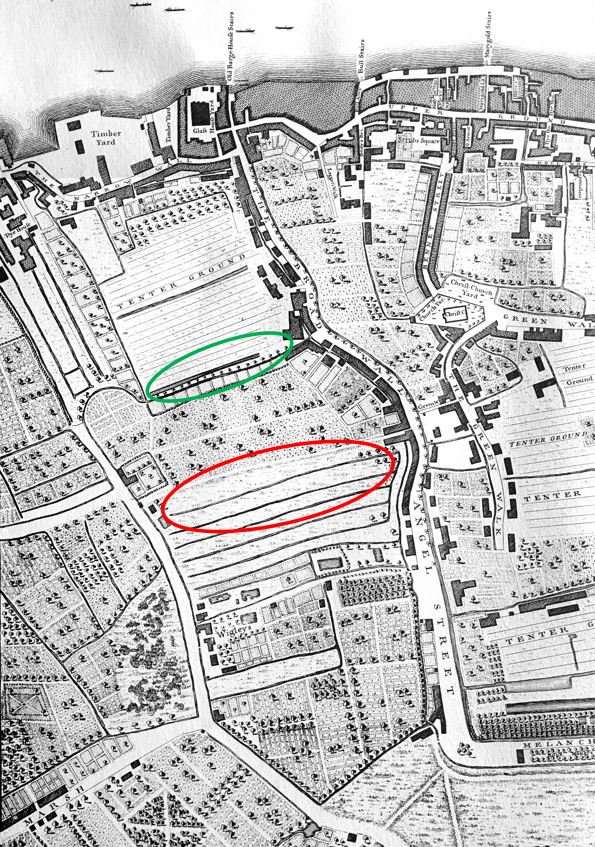

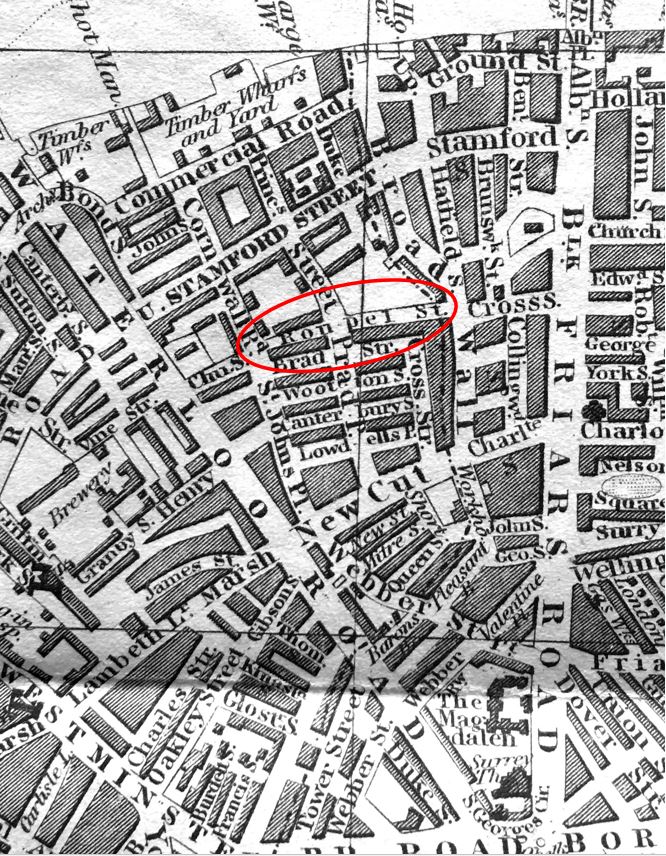

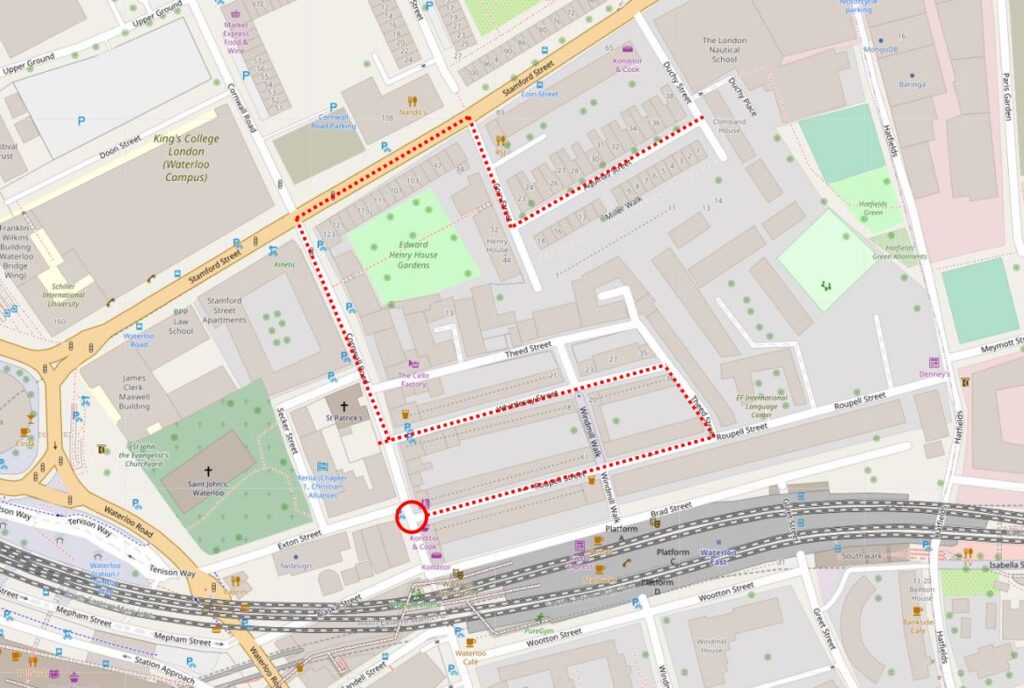

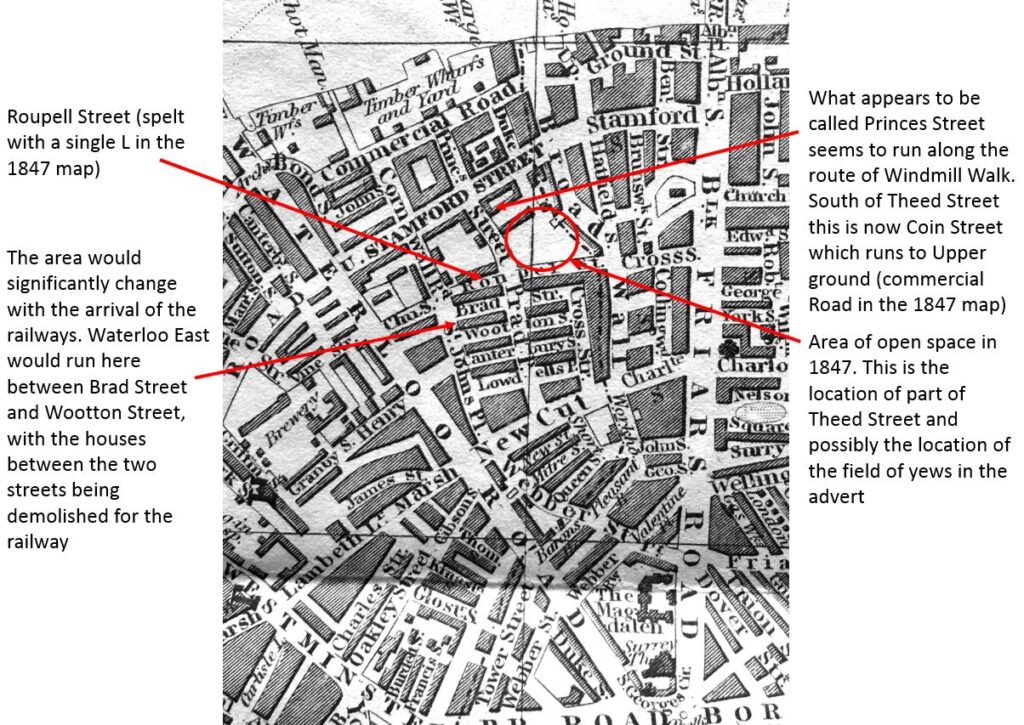

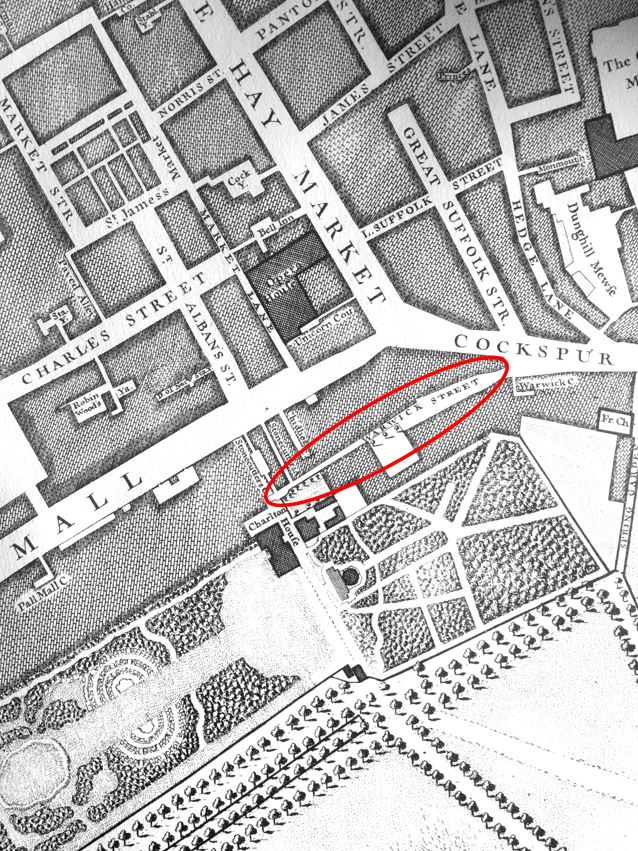

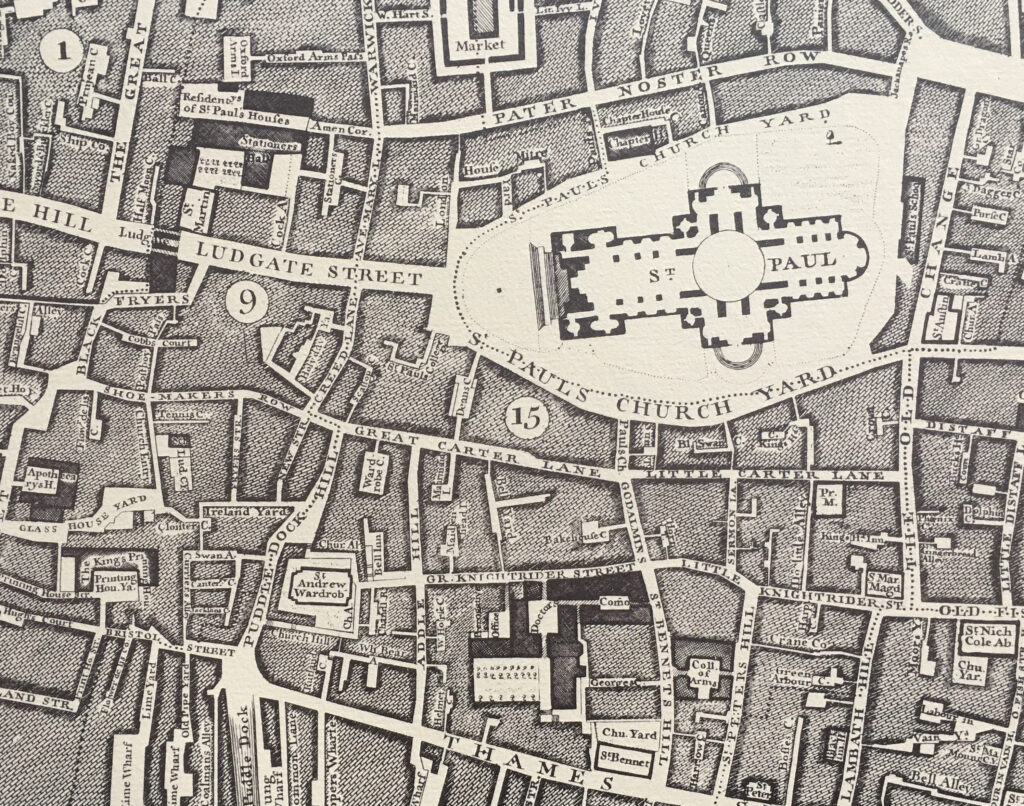

The Carter Lane of the above two maps, was not the original Carter Lane. To see the original Carter Lane, and many of the side streets and alleys that we can still find today, we need to look at Rocque’s map of 1746:

In the above map, running where Carter Lane is today, we find three named streets. From left to right: Shoe Makers Row, Great Carter Lane (underneath the circled number 15), and Little Carter Lane.

Harben’s “Dictionary of London” gives the first mention of the street as Carterstrete in 1295, with Great and Little Carter Lane’s appearing prior to 1677.

Great and Little Carter Lane, along with Shoe Makers Row were abolished in 1866 when the whole street became simply Carter Lane.

Many references on the Internet refer to the name of the lane being associated with carts, however Harben attributes the name: “the early forms of the name suggest that it was intended to commemorate a former owner of property there”. Many streets were named after either owners of the land, property on the street, or an original builder, so whilst is is impossible to be sure of the source of a centuries old name, Harben’s does sound the most probable.

Time for a walk along Carter Lane. In the following photo, I am standing at the junction of Carter Lane and Godliman Street, looking east.

This is the section that was Little Carter Lane in Rocque’s map.

Today, only one side is built, and the lane is a pedestrian walkway with gardens to the north. The area was badly damaged by fire during bombing on the night of the 29th December 1940 and the northern side of Carter Lane was not rebuilt after the war. It is now gardens, with the building on left being the City of London Visitor Centre.

Looking in the opposite direction, and the following photo shows the section that was Great Carter Lane in Rocque’s map of 1746:

Walking along the street, and the building on the right is the old home of the St Paul’s Cathedral (Choir) School.

Purpose built for the school in 1874, the school moved to a new building in New Change during the 1960s, when Carter Lane was threatened with a road widening scheme which thankfully was not carried out. The building is now one of the hostels of the Youth Hostels Association.

There is some rather ornate decoration on the walls of the old St Paul’s Cathedral School:

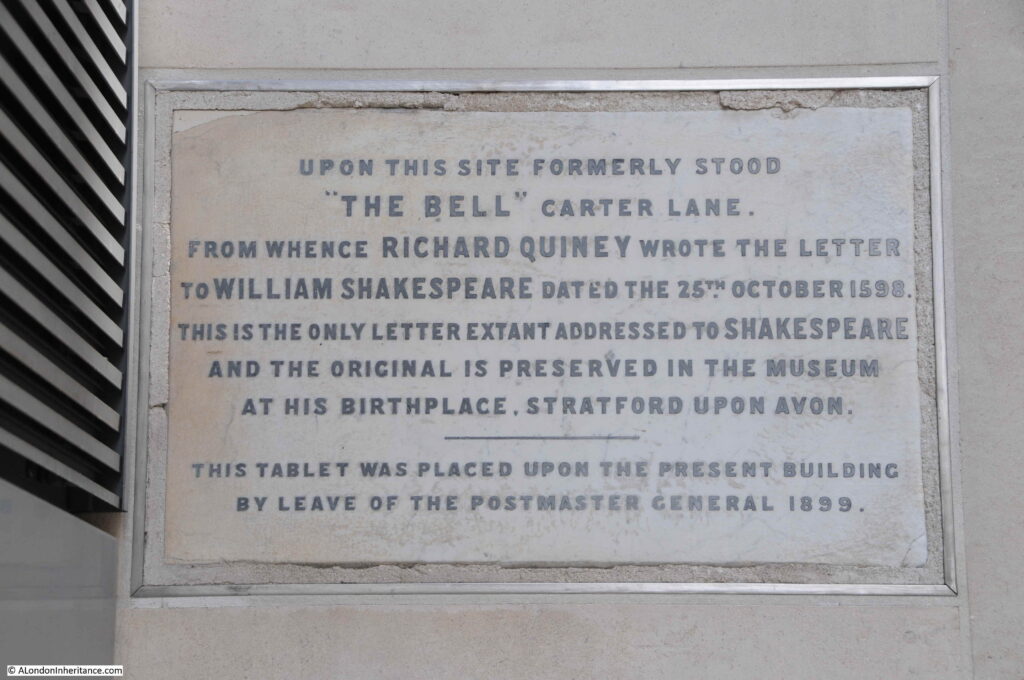

To the left of where I was standing to take the above photo, there is a modern building. Look carefully on the pillar to the right and there is a plaque:

The plaque records that the Bell originally stood on the site, and it was in the Bell that Richard Quiney wrote to William Shakespeare, and his letter is the only letter addressed to Shakespeare known to remain.

A photo of the letter can be seen on the site of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust here.

The Bell was a very old pub. The earliest written reference I could find to the pub dates from a report in the Kentish Gazette on the 12th October 1776, when it was reported that on the previous Sunday, Mr Milward, master of the Bell inn, Carter-lane, Doctors Commons had died.

The address of the Bell inn in the above report included “Doctors Commons”. Doctors Commons was the general name used for an area between Carter Lane and what is now Queen Victoria Street that included the College of Advocates and Doctors of Law, along with Ecclesiastical and Admiralty Courts.

The buildings were demolished in 1867 after the functions of the College and Courts had been consolidated into other roles, or been abolished.

In David Copperfield, Charles Dickens had Steerforth describing Doctors Commons as:

“It’s a little out of the way place, where they administer what is called ecclesiastical law, and play all kinds of tricks with obsolete old monsters of acts of Parliament, which three-fourths of the world know nothing about, and the other fourth supposes to have been dug up, in a fossil state, in the days of the Edwards. It’s a place that has an ancient monopoly in suits about people’s wills and people’s marriages, and disputes among ships and boats”.

The Bell was demolished at the end of the 19th century to make way for the Post Office Savings Bank building referenced in the plaque by the mention of the Post Master General. Prior to demolition, the Bell seems to have been a thriving establishment, as can be seen from this advert in the Morning Advertiser on the 24th February 1869 when the Bell was for sale due to the ill-health of the current proprietor:

“BELL TAVERN AND WINE-VAULTS occupying a most commanding corner position in one of the busiest and most improving parts of the City of London, close to St. Paul’s in a much frequented thoroughfare, and surrounded by many vast mercantile Establishments, affording an almost unlimited variety of sources of the best class of trade. The billiard-tables alone realise sufficient to pay the rent, and the extremely profitable nature of the business generally in the City is universally admitted”.

A shame that after the above sale, this centuries old pub would have less than thirty years left.

The Bell inn was on the corner of Carter Lane and Bell Yard which can be seen in the Rocque map. Bell Yard sort of still exists as New Bell Yard, an alley between two modern buildings:

As we walk further along Carter Lane, we come to the part that survived the fires that surrounded St Paul’s Cathedral during the 1940s. Epic Pies on the corner of Carter Lane and Addle Hill:

Addle Hill is worth a quick walk down, to see a survival from the late 19th century Post Office building, which can be seen half way down the building on the left:

Go back to the 1940 map, and on the block occupied by the building on the left of the above photo was a building called Faraday Building. This was part of the complex of Post Office buildings in the area that formed one of the London hubs of the growing telephone network.

The original late 19th century door surround to the Post Office building has been retained:

The plaque records that this was the “Former site of Faraday Building North, City, Central, Long Distance and International Telephone Exchanges, 1902 to 1982”.

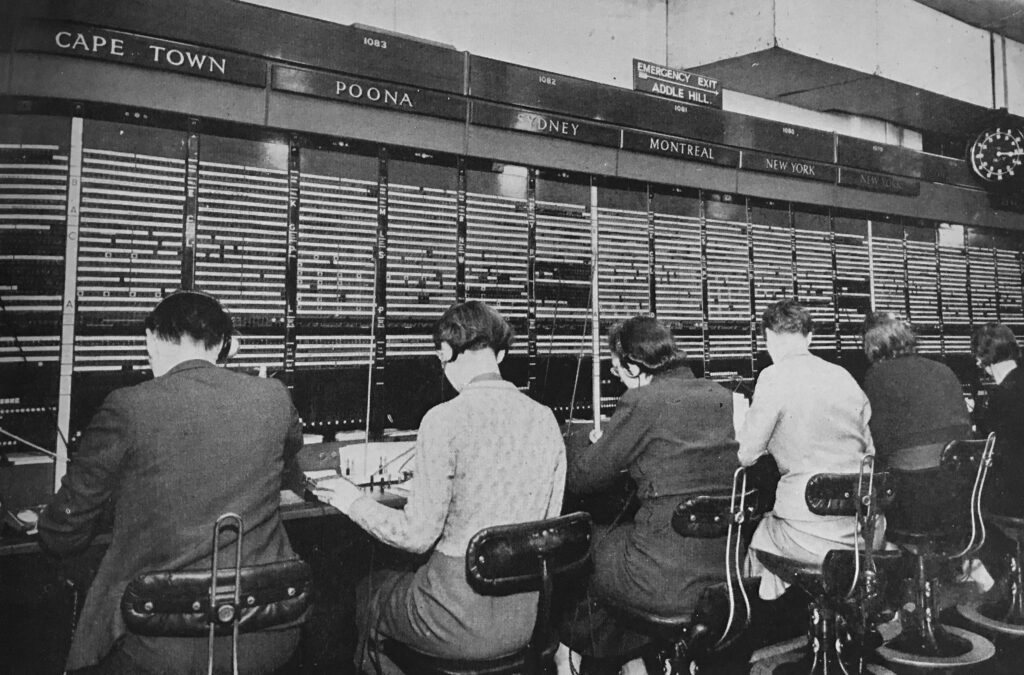

For much of the life of the Faraday Building, long distance and international telephone calls would need to be connected by an operator, and hundreds of operators worked in the building, sitting at desks labelled with the country that was connected to their desk. the operator would manually plug in patch cables to connect a caller to the destination’s telephone network.

An example of a small part of the operator positions in the Faraday Building is shown in the following photo (with Addle Hill labelled as the emergency exit above the Montreal position – from the booklet “The Post Office Went To War“):

Continuing down Carter Lane, and we can see the building that was the hairdresser in the photo at the top of the post, along with the Rising Sun pub:

But before we come to the home of the hairdressers, we pass the entrance to Wardrobe Place.

Wardrobe Place was so named as up until the Great Fire of 1666, it was the site of the King’s Wardrobe (the storage, administration and expenditure office for the King). The Wardrobe was moved here from the Tower in the 1360s into the mansion owned by Sir John Beauchampe. From Stow’s Survey of London:

“Then is the kings greate Wardrobe, Sir John Beauchampe, knight of the Garter, Constable of Dover, Warden of the Sinke Portes builded this house, was lodged there, deceased in the yeare 1359. His Executors sold the house to King Edware the third”.

We then come to the site of the 1980s hairdressers at number 59a Carter Lane. which was on the corner of Carter Lane and St Andrew’s Hill:

In between the hairdressers and becoming a food / coffee take-away and cafe, the site was home to KK Newsagents in the 1990s.

Although the café / takeaway has now closed, there are still a number of these in Carter Lane. We perhaps think that the vast number of such establishments on London’s streets is a recent phenomena, however there has always been a need to provide food and drink for those who lived and worked in the City.

In the 1895 Post Office directory, there were five listed:

- Number 29: Florence Jones-Albrt, Dining Rooms

- Number 55; Miss Sarah Ann Ash, Coffee Rooms

- Number 66; Miss Eliza Louise Catchpole, St Ann’s Coffee House

- Number 75; William Clemenace, Dining Rooms

- Number 79; Charles Batchelor, Dining Rooms

I suspect the number of such establishments can be used as a measure of the number of people working in the City, and similar to number 59a, many of these have closed over the last year.

St Andrew’s Hill leads down to Queen Victoria Street, opposite where Puddle Dock was originally located and according to George Cunningham in his 1927 Survey of London, was originally called Puddledock Hill (although I have been unable to find any other reference that confirms this, however it could well have been an earlier or alternative name as the street leads up from both Puddle Dock and the church of St. Andrew’s by the Wardrobe.)

One of the Bollards outside number 59a. This is different to the 1980s photo, and I am not sure of the age of either the bollard, or the City of London name panel which appears to slot over the bollard.

On the St Andrews Hill side of number 59a is a boundary marker on the right:

And an FP plate on the left. According to a document on the Essex Fire Brigade web site, FP stands for Fire Plug. Apparently in the early days of the fire service, and when many underground water pipes were made out of wood, firemen would dig down to the water main and bore a small, circular hole in the pipe to obtain a supply of water to fight the fire.

When finished, they would put a wooden plug into the hole, and leave an FP plate on a nearby wall to alert future firefighters that a water main with a plug already existed.

When wooden pipes were replaced by cast iron pipes in the 19th century, workmen would often bore a small hole in the pipe and fit with a wooden plug when they saw an FP plate.

This would later be replaced with the Fire Hydrant method, which would be identified by a large H.

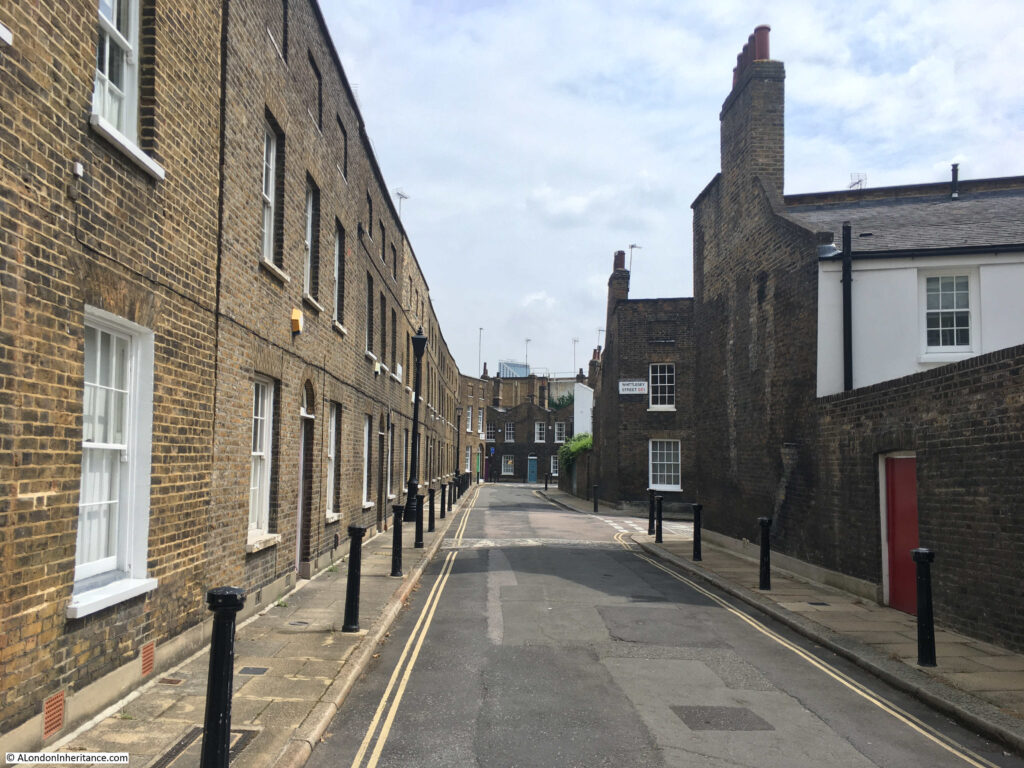

Just after number 59a, we come to the part of Carter Lane, that on Rocque’s map was in 1746 called Shoe Makers Row:

It is still a distinctive section of the overall street, as at the end of what was Great Carter Lane, the street narrows considerably into Shoe Makers Row.

However, before continuing further, there are a number of interesting buildings and streets at this junction of streets.

The building in the middle of the following photo once had a ground floor with symmetrical doors on either side, and possibly a much grander entrance or windows in the centre. It has now been modified somewhat by an entrance cut into the face, possibly as access to a goods loading bay or car parking. It is often how buildings survive over time in the City if not completely demolished, by being modified for different use.

On the corner of Carter Lane and Burgon Street is the Rising Sun, a Grade II listed, early / mid 19th century building, the Rising Sun is a typical City pub.

And to the right of the above photo, leading north from Carter Lane, is Creed Lane, another old City street that is currently blocked off as part of a building site:

Continuing on down Carter Lane, and although the previous section of the street was not that wide, the section that was Shoe Makers Row is a much narrower street. There are very few written references to the street, and I suspect that the original name of the street refers to the trade that was carried out here.

This section of the street feels older than the rest of Carter Lane, and leading off from the street are a number of alleys.

In the following photo is Cobb’s Court:

According to Harben, Cobb’s Court was first mentioned in 1677, and the name originally referred to a central court, with the passage leading down to Carter Lane (the section shown in the above photo) called Postboy Passage. We can see this original name in the extract from Rocque’s 1746 map at the start of the post.

Standing in Cobb’s Court, we can look across Carter Lane to another alley, this time leading south:

This alley has the rather unusual name of Church Entry:

Harben records that the name was first mentioned in 1677, and in 1559 was called Church Lane.

A short distance along Church Entry, there is a raised garden:

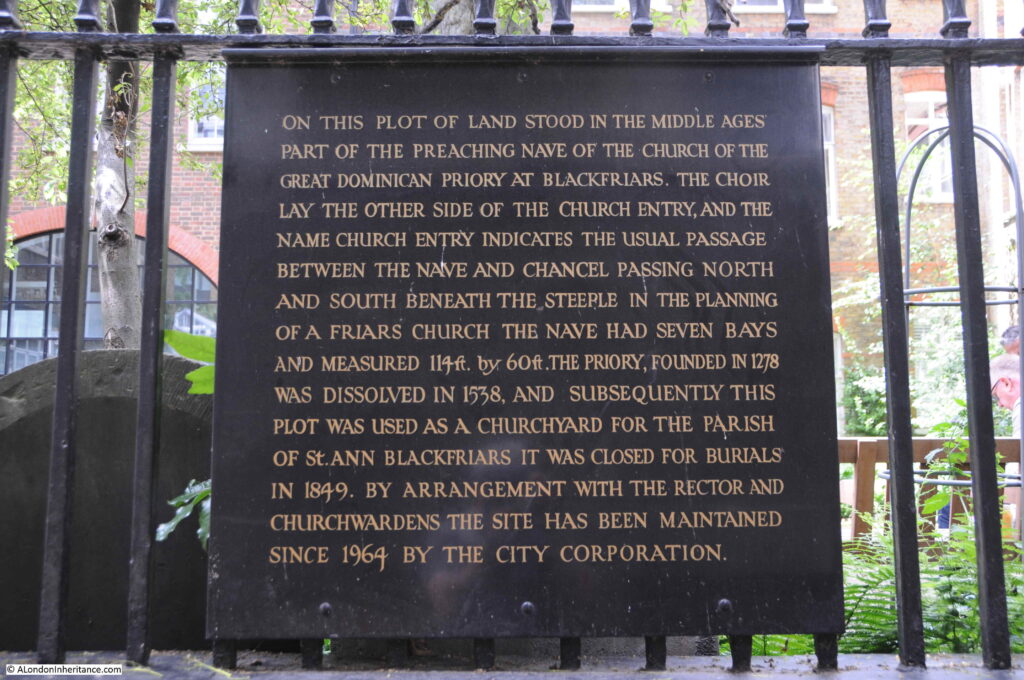

A plaque mounted on the railings providing some background as to the name of the alley, the garden, and the location being part of the church of the Dominican priory at Blackfriars.

After the dissolution, the land and buildings were sold, and it appears that Church Entry may have been formed when new, or perhaps a division of the existing buildings, allowed the alley to be formed.

The earlier religious nature of the area changed considerably over the following years, and we can get an impression of the street in the middle of the 18th century from the following report from Pope’s Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette on the 9th June 1763:

“Yesterday morning, about Three o’Clock, two young men, one a Peruke-maker, the other a Watch-maker, went into a House of ill Fame in Church Entry, Black-friars, when a Dispute arose about paying the Reckoning; on which the old Bawd gave the Barber a violent blow on the Head with a Poker, and called a soldier, who was then in the House, to her Assistance, who fell upon them with the aforesaid Weapon; the Watch-maker, in his Defence, drew a Knife and cut the Soldier cross the Belly, who was carried to St Batholomew’s Hospital, where he lies dangerously ill. The Barber has received a most dreadful Blow on his Head, several inches in length, quite to his Brain; and, with the Mistress of the House and one of the prostitutes, is committed to Clerkenwell Bridewell; and the Watch-maker, who is charged with wounding the Soldier, is committed to New Prison, Clerkenwell”.

It is fascinating to think about these events when standing in the alley, and the amount of individual stories that could be told about every London street and alley is one of the overwhelming things about researching the city.

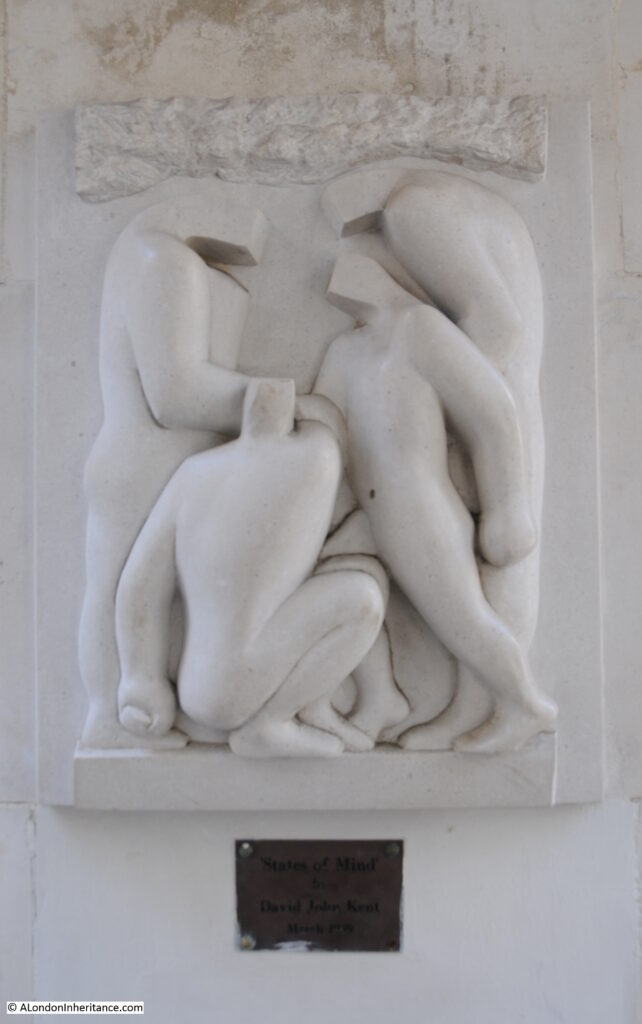

There is one rather unqiue building remaining in Church Entry:

This is the Vestry Hall of St Ann’s Church.

Although the church of St Ann’s was not rebuilt after the Great Fire in 1666, the vestry hall seems to have continued. The building we see now is much later than the original church, having been built in 1905 and is now Grade II listed.

St Ann’s Vestry Hall is now home to the Ancient Monuments Society and the Friends of Friendless Churches.

Walking back up to Carter Lane, and a little further along are two rather special buildings. Both of these buildings, although considerably changed over the years, date back to the late 17th century. On the left is 79 Carter Lane, and part of number 81 is on the right.

They are both Grade II listed, and the Historic England listing for number 79 reads:

“Possibly late C17, stuccoed in C19. 3 storeys plus continuous dormer. 2 windows. Shop. Corniced 1st floor windows. Crowning cornice and parapet.”

“Late C17, stuccoed and altered. 3 storeys plus continuous dormer in roof. 3 windows. Shop and passageway. Storey-bands. Parapet.”

Remarkable to think that there could be buildings that at their core date back to the late 17th century in the heart of the City.

I started the post with a hairdresser / barber, and I am almost finishing the post with another one, as at ground level at number 79 is the closed Carter Lane Barbershop.

Under number 81, and between numbers 79 and 81 is another alley, Carter Court:

Referring back to the Rocque map, and in 1746, Carter Court was called Flower de Lis Court. I double checked this with Richard Horwood’s map of 1799, and the same name appears to cover the court.

There were a number of alleys and courts in London with variations on the Flower de Lis name, and no clear source for the name, with a number of possible origins including the name of a wharf, a tenement, or a tavern.

Walking down what is now Carter Court, and looking at the wall of number 81 we can get a sense of the age of the building and the construction methods and materials used as the building has been repaired and modified over the centuries. It is extremely rare to see this exposed form of construction.

Further down the court, there is more evidence of the early date of construction, and at the end, a small window opening into the court.

I have now reached the end of Carter Lane, the point where the street meets Ludgate Broadway and Black Friars Lane. Looking back up the street, to what was Shoe Makers Row, with the oldest buildings on the street, numbers 79 and 81, on the right.

With the exception of the part of the street that was Little Carter Lane, and the western end of Great Carter Lane, the rest of the street was not destroyed by wartime bombing. Victorian building along the street was relatively modest, and much of this 19th century and early 20th century building occupied the original plots of land.

Carter Lane is today part of the St. Paul’s Cathedral Conservation Area which should give the street some protection.

A street that is well worth a walk, and where a sense of the historic City of London can still be found.