Today, Remembrance Sunday, the focus will quite rightly be on the 100 year anniversary of the end of the First World War. 1918 was the end of what was hoped to be the “war to end all wars”, however in just over 20 years time, the world would descend into yet another global conflict.

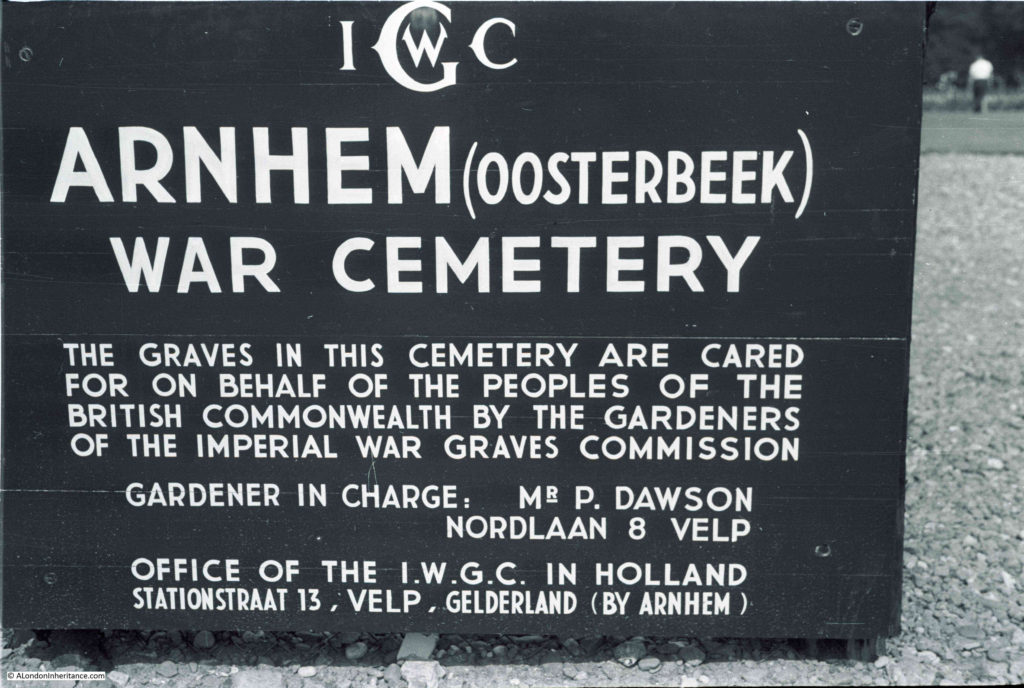

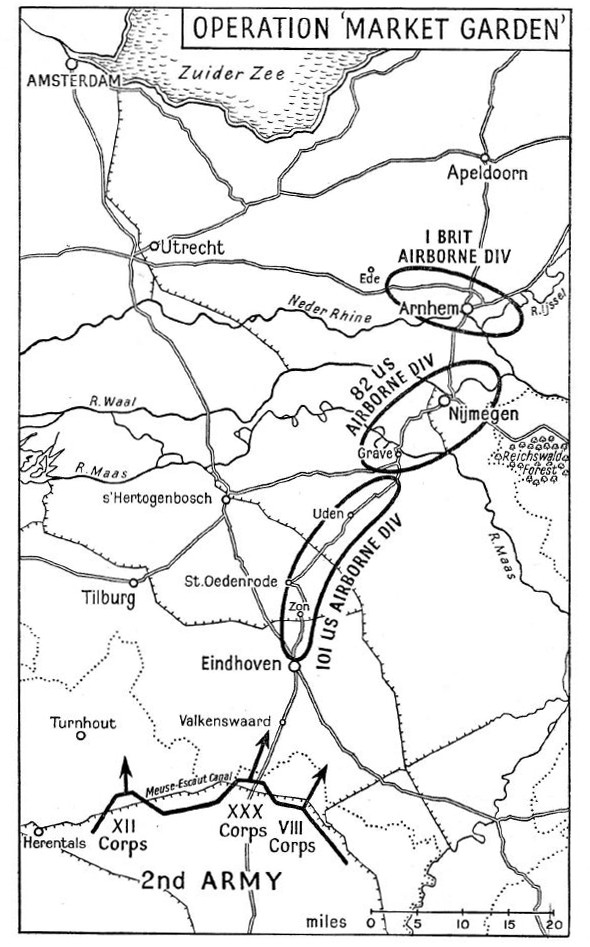

The Second World War would add to the cemeteries created for the victims of the first war and during my visit to the Netherlands this year I went to the Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery, a place that my father had already photographed during his visit to the Netherlands in 1952, not long after the cemetery had been created for the dead of Operation Market Garden and other conflict in this part of the Netherlands.

In 1952, this was the sign at the entrance to the cemetery:

The entrance to the cemetery today:

The following photo provides some indication of the size of the Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery. A central grassed space runs down to a cross at the far end. On either side there are row upon row of gravestones, each representing a person, someone who died in the fighting around this part of the Netherlands.

When my father was at the cemetery in 1952, it was still being completed. At the end of the war, the task began of recovering the bodies and burying them in the cemetery. During Operation Market Garden, the dead would usually be buried where they fell, and the grave marked with a temporary wooden cross made from whatever materials were to hand.

Identities had to be confirmed and stone gravestones were made for each grave. In 1952, a number of graves still had the temporary crosses used for the initial burial at Oosterbeek.

There were a number of graves that I wanted to find as the names were clear in my father’s photos. The first was Lieutenant J. C. Crabtree, named on a cross at the end of a line of graves towards the far end of the cemetery. In 1952, this section of the cemetery still had the temporary crosses.

The same graves today:

J.C. Crabtree was Jack Colin Crabtree who died on the 21st April 1945 at the young age of 20.

The son of Herbert Beaumont Crabtree and Dorothy Crabtree, in the 1939 census they were recorded as living at 13 St. Margaret’s Avenue in Luton, the house is still there. Jack’s father was listed as a Suprt Body Builder Motor and was obviously employed in Luton’s car manufacturing industries. Dorothy was described as Unpaid Domestic.

Jack Colin Crabtree was a Lieutenant in the Green Howards (Yorkshire Regiment). His death was in the closing months of the war, the Netherlands were fully liberated in May 1945 when the surrender of the German forces in the country was negotiated on the 5th May 1945.

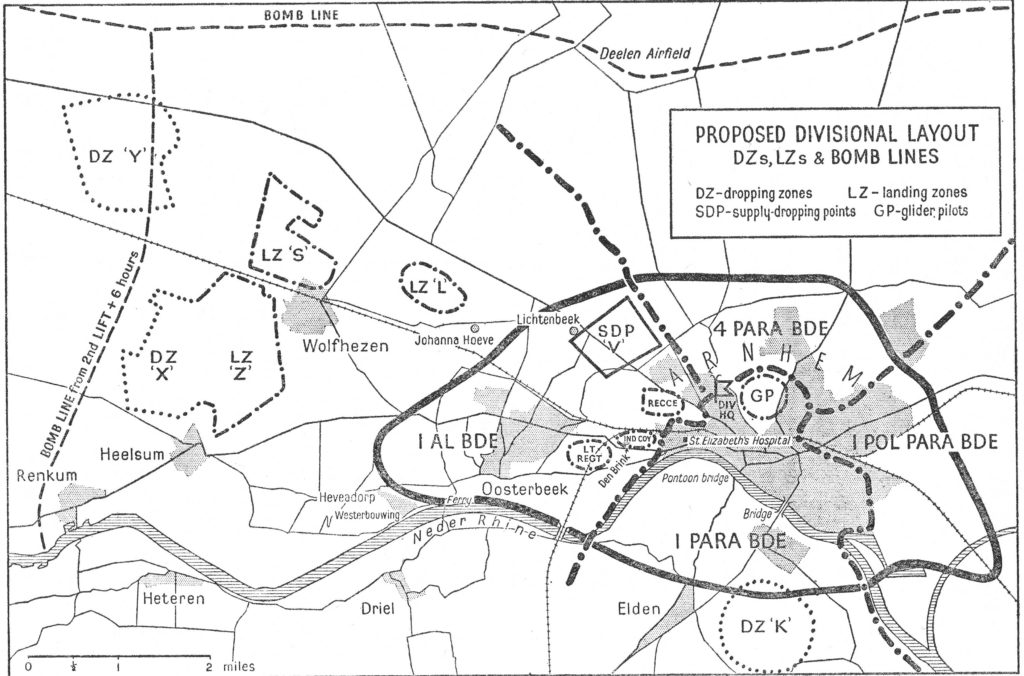

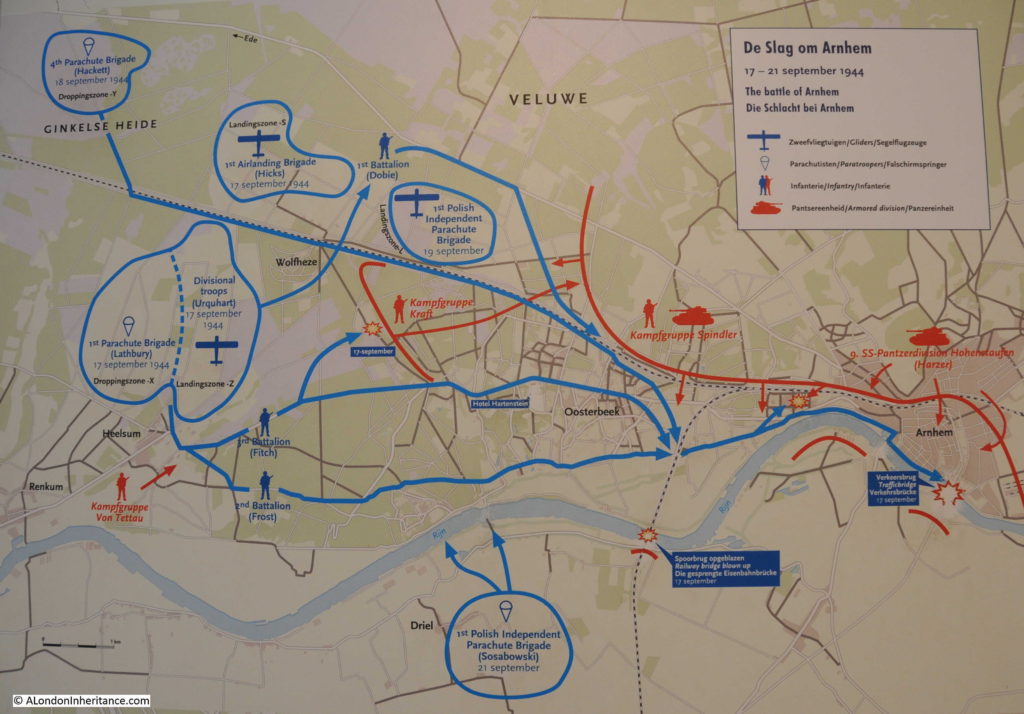

Another grave I wanted to find was of a soldier in the Polish Parachute Brigade. The Polish parachute forces landed south of the river, opposite Oosterbeek in the closing days of Operation Market Garden when the British forces were being pushed into a tight perimeter in Oosterbeek. The Polish landing date had been delayed by fog on the English airfields and when they landed the Germans were prepared for their arrival and the Poles suffered terrible casualties.

They managed to establish and hold a perimeter south of the river until the arrival of the main land forces which enabled the withdrawal across the river of the surviving British troops from Oosterbeek. A number of the Polish soldiers made it across the river to help man the ever shrinking Oosterbeek perimeter,

This is the original, temporary cross at the grave of Private M. Blazejewicz:

This year, I photographed the permanent gravestone:

Some of the details on the original cross appear to have been corrected on the later headstone. The date of death has changed as well as his rank.

The grave is of Mieczyslaw Blazejewicz, with a rank of Starszy Strzelec (this seems to translate to a Senior Private or Lance Corporal) in the 3rd Parachute Battalion of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. He was born on the 24th November 1920 at Lancut, a town in south eastern Poland.

He was killed whilst trying to cross the River Rhine to get to Oosterbeek on the 26th September 1944. As with many of those killed whilst trying the cross the river, his body would drift downstream and his body was recovered from the river at Rhenen on the 9th October. He was 23, just two months short of his 24th birthday.

There are a number of Polish soldiers buried in the Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery. Their gravestones are distinctive by having a more dome shaped top, unlike the other gravestones.

As you walk along the rows of graves, reading the inscriptions, one thing that always stands out is the very young age of those who fought and died. The majority are in their twenties, however there are many who were 18 or 19.

This is the grave of Private Dennis William Harrison of the 2nd Airborne Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment. Dennis was 18 years of age when he died on the 24th September 1944, the day before the survivors who still held a shrinking perimeter in Oosterbeek were given the order to withdraw across the Rhine.

The South Staffordshire Regiment arrived over two days. The majority arrived in the first day of the campaign, Sunday 17th September, with the remainder of the regiment arriving on the following day. It is probable therefore that 18 year old Dennis William Harrison was fighting from the 17th September until his death on the 24th September. In the 1939 census, Dennis father was recorded as a Coal Mine Charge Hand and his mother Annie was recorded with Unpaid Domestic Duties. They lived at Ballinson Road, Blurton , Stoke-on-Trent, in a house that is still there.

This is the grave of Leading Aircraftman R. J. Eden in 1952:

The same gravestone in 2018:

It is lovely to see that the Jewish tradition of leaving stones on the gravestone to show that you have visited the grave is in evidence on R.J. Eden’s grave, as well as a number of other graves of Jewish soldiers in the cemetery.

According to the Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery records, R.J. Eden was Roffer James Eden, serving with 6080 Light Warning Unit as part of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve.

The Light Warning Units were one of the many specialised roles in an airborne force. They were equipped with Light Warning equipment which was used to signal and coordinate with fighter aircraft providing cover for the ground forces. The Light Warning equipment was just about small enough to fit into a pair of Horsa Gliders. Four gliders were used to transport the Light Warning equipment on the second day of the campaign. Each pair of gliders held a complete set of equipment so in theory loss of one, or a maximum of two gliders would allow one set to arrive safely, however the transport plane for one glider was hit by flak and crashed, and the second glider was also hit by flak and crashed. By chance, both the crashed gliders were the same one from each pair, so the two gliders that arrived safely were each carrying the same half of the equipment needed to build an operational Light Warning Unit.

Once on the ground, and if they could not perform their primary role, Roffer James Eden, along with other roles such as glider pilots would fight alongside the other forces.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records that Roffer was the husband of Annie Eden of Victoria, London. Despite the unusual name, I have not been able to track down any details of Roffer James Eden. The transcript of RAF deaths records his first names as “Roffer J or Eckstein Jacob”, however I have also not been able to find an Eckstein Jacob Eden.

There are many graves across Oosterbeek cemetery where the identity of the person is unknown.

In the following photo from 1952, a block of graves have the temporary crosses. The grave nearest the camera is marked as ‘unknown’ that on the right only has a date. Behind there is the grave to a Corporal, but with no name, and a bit further to the right another unknown soldier.

In the following photo from 1952 there is a cross on the left with 6 names.

I checked the names which are fully visible and they are all from 570 Squadron of the Royal Air Force. and they appear to be a full crew from a single plane.

Robert Carter Booth, aged 22 was a Flying Officer, Navigator. Francis George Totterdell, aged 24 was a Pilot Officer, Wireless Op./Air Gunner. Dennis James Blencowe (no age recorded) was a Flight Sergeant, Air Gunner. John Dickson, aged 24 was a Flight Lieutenant, Navigator.

To add to the evidence that they were all on the same plane, their date of death was the same, the 23rd September 1944.

570 Squadron was based at RAF Harwell in Berkshire. They flew Short Stirling aircraft and during Operation Market Garden they operated as tugs for the Horsa Gliders for the initial drops, then until the force at Oosterbeek was withdrawn they ran supply drops. Most of these were unsuccessful as the Germans had overrun the drop zones and the soldiers on the ground had no working radios to communicate with the aircraft.

Written accounts from those on the ground at the time tell of the bravery of the RAF crews making the supply drops. They would fly in relatively low and slow and many aircraft were lost after being hit by high levels of German fire from the ground and attacks by German fighter aircraft.

In his book Arnhem by Major-General Urquhart, the commanding office in Oosterbeek, he writes of the supply drops:

“Twice in the afternoon the RAF tried to get supplies to us. Their first mission at 12:45 pm was disastrous. The aircraft were shot up by ME109s before our eyes and there was some evidence that the Germans were using our signals to attract some of the supplies. The second mission at 4 pm was much more successful and we acquired a small proportion of the sorely needed ammunition and rations as they fell. It was a costly day for the RAF, whose losses were twenty per cent of the aircraft taking part”.

Also on another drop “Again, the ground signals were laid and lit, and the troops held out parachute silks. But the aircraft kept to the planned dropping points and the Germans again found themselves receiving gifts from their enemies. only the overs reached us. Some crews, overshooting, came round in the face of most appalling flak. Some aircraft were on fire. Hundreds of us saw one man in the doorway of a blazing Dakota refusing to release a pannier until he had found the exact spot, though the machine was a flaming torch and he had no hope of escape.”

As their date of death was the 23rd September, this was towards the end of the campaign and would have been during one of the attempted supply drops.

Another of my father’s photos of the cemetery in 1952.

And another of the many graves to unknown soldiers.

Temporary crosses:

Some of the graves have photos of those buried.

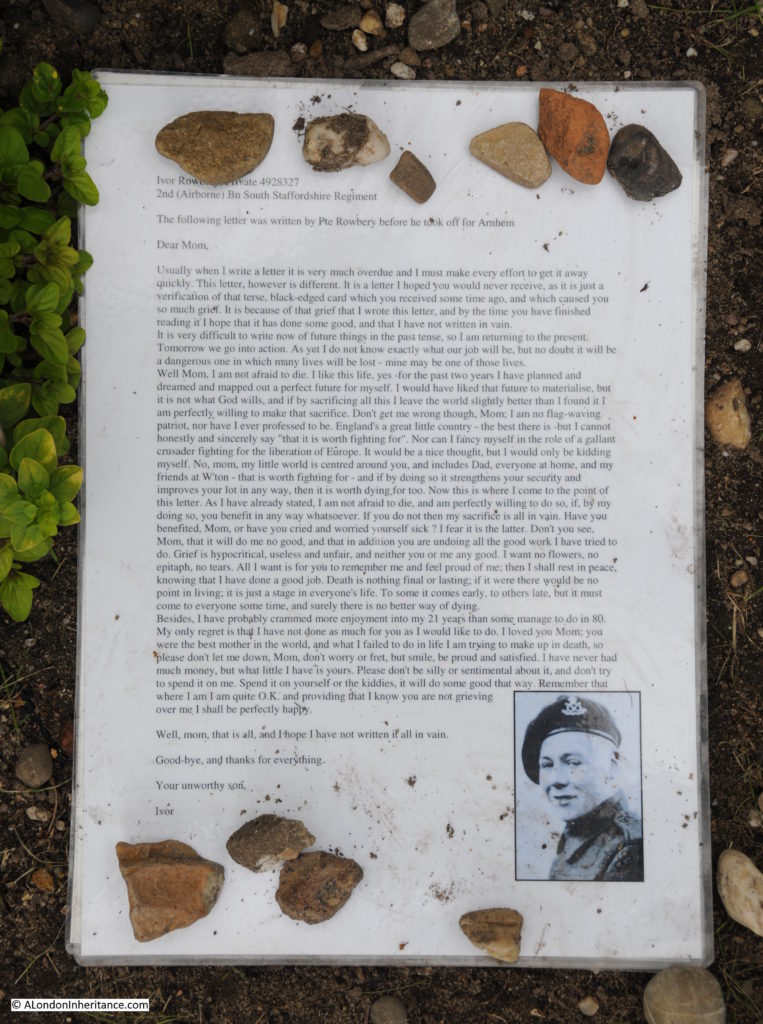

This is the grave of Private Ivor Rowbery of the South Staffordshire Regiment. He was 22 years old when he died on the 22th September 1944 when a mortar hit his gun pit near the Oosterbeek Old Church.

By the gravestone is a copy of a letter he wrote just before leaving the UK for Oosterbeek and Arnhem. It was the letter that would be sent to parents, wife, next of kin in the event of the soldier’s death in battle. Ivor Rowbery addressed the letter to his “mom”. (Click on the photo for a larger photo – it is a letter that should be read)

It is a wonderful letter, no nationalistic flag waving, just a quiet pride in his home and family, and concern for his mother should he be killed in the conflict.

Next is the grave of William Frank Lakey, aged 23 and a private in the Parachute Regiment. He came from Upper Holloway, London. A photo provides a reminder that all these gravestones are for individuals who died at far too young an age.

Looking down from the entrance to the rear of the cemetery:

The view from the cross at the far end of the cemetery towards the entrance. Row upon row of gravestones for those killed in action during Operation Market Garden or from other fighting as this part of the Netherlands was liberated.

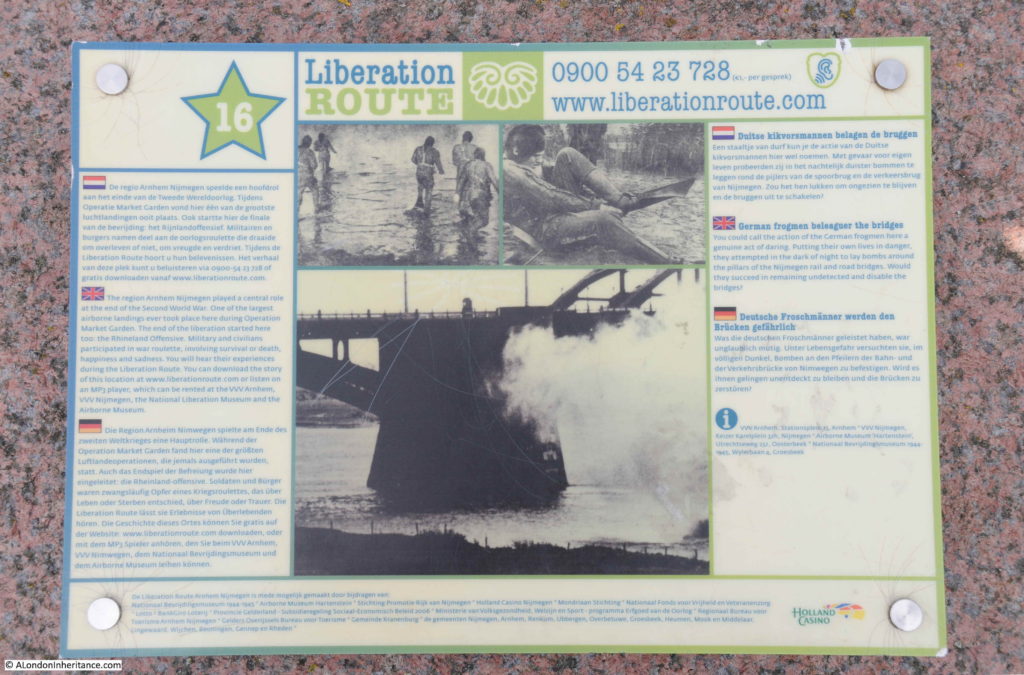

The events in and around Arnhem and Oosterbeek in September 1944 are still commemorated every year with events such as the Airborne Wandeltocht and other commemorative ceremonies. One of which is when children of the area place flowers on all the graves in the Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery. A plaque in the entrance commemorates this annual event.

A photo from the Imperial War Museum archive shows the first time this ceremony took place.

THE BRITISH AIRBORNE DIVISION AT ARNHEM AND OOSTERBEEK IN HOLLAND (BU 10741) Dutch children pay their respects to the fallen and lay flowers on the graves. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205192049

The ceremony still takes place, and this year on the 23rd September the children whispered the name of the person buried as they place flowers on the grave.

It is too easy to be overwhelmed by the number of graves in war cemeteries, however it is so important to remember that each one was an individual with hopes and ambitions for the future, with a family, with a life back in their home country.

Today, as well as my Great Uncle Arthur who died in the First World War, on the 30th October 1918, I shall be remembering William Frank Lakey, Ivor Rowbery, the crew from 570 Squadron on a resupply mission in their Short Stirling aircraft, Roffer James Eden, Mieczyslaw Blazejewicz, Jack Colin Crabtree and all those buried in the Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery.