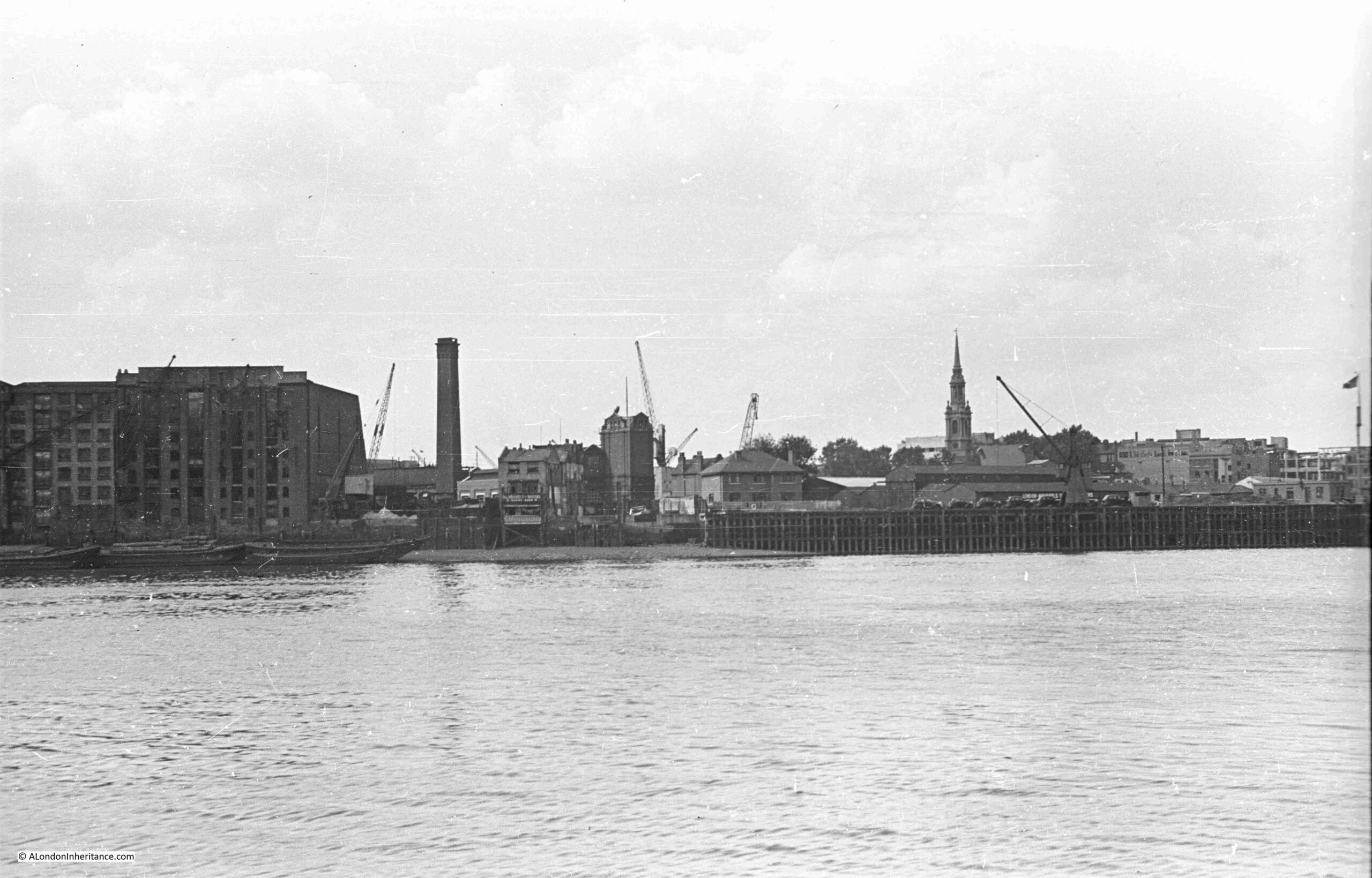

For today’s post, I have another of my father’s photos, taken on a boat trip along the River Thames in August 1948, this time looking across to Wapping, the Prospect of Whitby and Pelican Stairs:

The same view in 2024, some 76 years later:

The 1948 photo shows an area just three years after the end of the war, and the bombing that badly damaged the whole area of the docks. It was a dirty, industrial place, still important in supporting the trade of London and the country, with imports and exports through the docks.

Only a few buildings have survived the intervening 76 years. The Prospect of Whitby pub, today a brightly painted white building along the river. The brick building behind, the steeple of the church of St. Paul’s, Shadwell, and on the left edge of both photos is a warehouse (1948) now converted to flats.

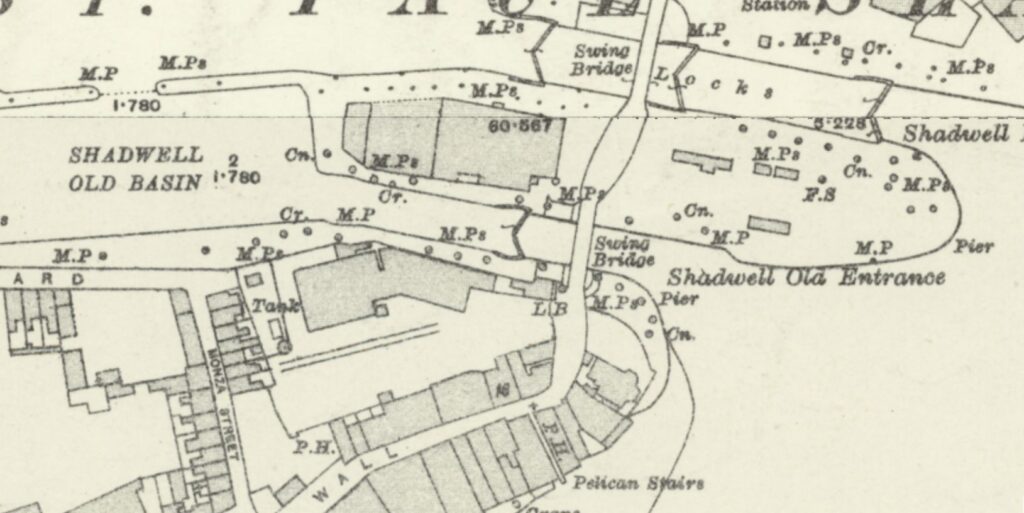

The following extract from the 1949 edition of the OS map shows the area along the Thames featured in the photo, as well as the area behind (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

The Prospect of Whitby can be seen roughly in the middle of the map, and to the left of the pub is Pelican Stairs and Pelican Wharf. Just to the left of the P in Pelican is a square which marks the position of the chimney seen in the photo.

An extract from the photo provides a closer look at the Prospect of Whitby and surrounding buildings:

On the left is Pelican Wharf, then the Prospect of Whitby, with Pelican Stairs descending immediately to the left of the pub, then in the background, the large brick building of the London Hydraulic Power Company.

The same view today:

A new apartment building has been built over Pelican Wharf. The first mention I can find of Pelican Wharf dates from December 1866, when the wharf was mentioned in an article about a collision in the river opposite the wharf.

Many of the apartment buildings in my 2024 photo were part of the late 1980s development of the area, and there is an article in the Brentwood Gazette from the 22nd of April, 1988 which mentions Pelican Wharf, and provides a reminder of the transformation of the 1980s:

“Six months after Black Monday the Docklands property market is experiencing a ‘new realism’, says Stephen Miles-Brown of estate agents Knight Frank & Rutley.

The Essex bookmakers and the South London car dealers – the ‘Top Gun’ speculators of yesteryear – have all but disappeared, says Mr. Miles-Brown. In their place has come the traditional buyer with a mortgage, a career and even a few children.

Docklands developers are in the middle of the strongest buyer’s market for years. They have responded quickly and imaginatively. Immediately post Black Monday, there were incentive schemes, buy-backs, chain breaking and mortgage discounts, now the latest and perhaps best news of all is the return to good old fashioned ‘value for money’, a code word for keen prices, more space and upgraded specifications.

These developments with a large degree of space and higher specifications are far removed from some of the earlier ‘little boxes’ and are to be found throughout Docklands in such places as Timber Wharf on the Isle f Dogs, Greenland Passage in the Surrey Docks, Lime Kiln Wharf and Duke Shore Wharf in Limehouse, Pelican Wharf and Eagle Wharf in Wapping and Millers Wharf by St. Katherine Docks.

April marks the start of the 1988 ‘Docklands Season’ with no less than 10 major residential developments coming forward over the next few weeks.

They offer the choice of over 500 new homes, from first-time buyer studios at under £100,000 to – only for the seriously rich – 3,000 sq. ft. penthouses at £1.5 million !”

The later half of the 1980s and into the 1990s really was a development rush along the banks of the Thames, and although the article described the situation as a buyers market, prices for river facing properties in the 1980s were expensive. A first time buyer’s studio for under £100,000 may seem really cheap today, but in 1988 this was expensive.

In the above 1948 and 2024 photos showing the Prospect of Whitby, a set of stairs can be seen running down to the foreshore to the left of the pub. These are Pelican Stairs.

Pelcian Stairs are listed in the Port of London Authority listing of access points to the Thames as being in use in 1708, and they are certainly old stairs. Their location next to a pub is typical of many of the stairs in Wapping, as many users of the stairs, whether arriving back, or waiting to leave via the stairs, would have headed to the pub, and the combination of stairs and pubs were centres of local activity.

The Prospect of Whitby was originally called The Pelican, but it is not clear where the name was used first, either the stairs or the pub.

The PLA listing (published around 1995) recorded that the stairs then had “Steps missing dangerous, derelict”.

As can be seen today, the stairs are now very much in use:

The first written reference to Pelican Stairs I could find was from the 30th of August, 1746, when the Kentish Messenger reported that “On Tuesday Evening, a Fire broke out in the House of Mr. Pelham, near Pelican Stairs in Wapping, occasioned by a quantity of Okum taking Fire; which burnt with such Violence, that the same, and the House of Mr. Beane, a Distiller and Grocer, were consumed, with their Stocks in Trade, which amounted to several hundred Pounds; two other Houses, both inhabited, and other small tenements were much damaged.”

It is remarkable the number of fires that occurred, but perhaps not surprising when you consider that there were many houses, warehouses and factories where highly inflammable goods were stored, and where both building and working practices lacked the approaches needed to prevent the start and spread of fires.

The entrance alley to Pelican Stairs alongside the Prospect of Whitby:

The large brick building behind the Prospect of Whitby can be seen in both 1948 and 2024 photos. This was the Wapping pumping station of the London Hydraulic Power Company.

The London Hydraulic Power Company (LHPC) was formed in 1884 by Act of Parliament, although the provision of hydraulic power by the company had started in the previous years with a station at Bankside, as the Wharves & Warehouses Steam Power & Hydraulic Pressure Company.

The aim of the company was to provide hydraulic power (water under pressure), across London, and the docks were a major consumers of this form as power, as there were numerous cranes, lifts, swing bridges, dock gates, windlass etc. which needed a reliable source of power to operate.

The LHPC established a network of pipes across London, interconnecting their pumping stations and their consumers – much like the electricity network of today – and as well as the London Docks, the company provided power to the numerous, power hungry industries and businesses across London, even extending to the raising and lowering of theatre safety curtains in the West End.

The Wapping pumping station was built between 1889 and 1892.

The station was equipped with up to six steam engines which used coal delivered via the adjacent Shadwell Basin, and took water from boreholes below the station and from the water in Shadwell Basin.

The large brick building we can see in the photos was were the accumulator tanks were located. These held water at pressure, so the hydraulic pressure across the distribution system could be delivered at a constant pressure, and the London system was at a pressure of 750 psi (pounds per square inch).

The Wapping station transitioned to electric pumping rather than steam and coal due to the Clean Air Act which had been brought into force due to the smog’s of the 1950s.

Remarkably, the Wapping station did not close until 1977, as hydraulic power was still being used, however by the 1970s, the reduction in the use of the London docks, and the transition to electric power for remaining uses of hydraulic power resulted in the closure of the station, and the network used to deliver the hydraulic power delivered by these stations.

With the 1980s liberalisation of telecommunications, and the forming of Mercury Communication as a competitor to BT, Mercury purchased the pipe network of the London Hydraulic Company to use as a ready made distribution network for their cables.

Although Mercury as a brand name disappeared in 1997, the pipes continued to be used by Cable & Wireless, and they still carry fibre optic cables today, so rather than distributing hydraulic power, the pipes are distributing voice and data across London.

The Wapping pumping station has had a number of temporary uses since closure, including activities such as an art gallery and café / restaurant, and there have been proposals for long term use, but as far as I know at the moment, there are no firm plans for the building.

Looking at another part of my father’s photo, and there was a bit of a mystery, but which shows how features remain hidden and then are revealed.

The following photo shows the area to the right of the Prospect of Whitby in my father’s 1948 photo:

And this is the same view today:

The 1949 OS map shows this section of the photo, as shown in the extract above, and the black cars parked in a line (possibly awaiting loading on a ship for export), are parked where the words “Mooring Posts” can be seen (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

The map also shows the low warehouse behind the cars and what also likes rather like a domestic house to the left of the photo.

The mystery is that in 1949 photo and map, at the side of the river there is a continuous and straight line of wooden posts forming the edge of the land, however if you look at my 2024 photo, today the wall along the foreshore is curved, and to the right there is a solid, curved, concrete wall.

If we go back to the 1897 OS map, we can see a very different place (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

We can still see the main entrance between the Thames and Shadwell Basin at the upper part of the map, but in 1897, below the main entrance, was “Shadwell Old Entrance”.

The London Docks were a continuous building site, and in Shadwell, the “Shadwell Old Basin” and the “Shadwell Old Entrance” were the first part of the docks to be built in Shadwell.

The success of these docks was such, that they were soon expanded and the much larger Shadwell Basin was built, just north of the Old Basin, which was included within the overall Shadwell Basin.

The old entrance would then be closed off, with the single main entrance shown in the 1949 map remaining as the eastern entrance to Shadwell and the London Docks complex.

I assume that the the original entrance was built over, probably not completely removing and filling in the entrance, rather building over it to complete the view we see in the 1948 photo and 1949 map.

When the area was redeveloped in the 1980s and 90s, this structure was then removed, and the curved concrete wall built across what remained of the Shadwell Old Basin entrance.

It is fascinating how across London, the evidence of former land use, industries etc. have survived and can still be seen today.

To see the street side of the Prospect of Whitby and the lifting bridge over the Shadwell Basin entrance, see this post from 2016, where I explored my father’s photo taken in Glamis Road.

Know this area well and £100k for a studio was pretty over the top in the 80s. The Black Monday recession decimated the housing market which took nearly a decade to recover elsewhere but Docklands then began ascending.

The London Hydraulic company had long ceased operation but a speculator realised that the old pipe network went into practically every building in the City. He sold it for a very handsome profit to Mercury who in turn saved millions. Mercury quickly installed it’s digital network. It then used the canal network to link the rest of England as the old canals went everywhere.

With all the opportunity to build on an industrial scale, the best developers could design are these hideous Soviet style blocks of flats. They won’t stand the test of architectural time that’s for sure. Terribly sad.

The valuable historical photographs are fascinating.

Lovely post

Great read and perfect timing – we happened to have a lunchtime booking today at the Prospect of

Whitby, coinciding with the release of your post, making it all the more fascinating! A wonderful read.

Love your posts and makes me homesick for not only London but in some ways for a past time.

In reference to buildings appearing in both photos, you didnt mention the other brick house, which can just be seen behind the other larger residential looking house in the 1948 photo. Hard to see in black and white as the brick doesn’t stand out, but you can see the very top of the gabled end in what I think is called Dutch style (I’m probably all wrong with my terms) and the two chimneys. In the 2024 colour photo the fancy dutch gabled house is very evident between the pub and the flats with red balconies, because the other residential house has been demolished. I’d love to know a bit about the history of those two houses. I wonder if the house that was pulled down, that looks relatively modern in the 1949 photo, maybe 1920s or 30s, was something to do with employees at higher level at the docks or pumping station?

A very interesting read as usual particularly the information on the London hydraulic company and the use of the pipe network-great stuff

Wonderful read full of details.

My ancestors were Thames Lightermen. I have discovered nine in my family dating back to the early Victorian period.

Mine too were lightermen going back in Victorian times . My grandfather born in Cable street in 1891. Family name Wilson.

When leaving school in 1955 my first job was with a shipping company that had offices located on the Jetty in the Western Basin of the London Dock. During my time there I was ‘introduced’ to the Prospect of Whitby which then was just a dockers pub, although somewhat better than the two opposite the dock gates in East Smithfield. I have never been back since. In the 1980s I was employed by Cable & Wireless and was able to look at a number of documents it inherited when taking over London Hydraulic Company. All the cranes in the London Dock were hydraulically operated and it was interesting to see the plans of the pipe layout in the dock.

Just to say thank you so much for all the wonder information and pictures you provide on this site.

I noticed the revealed building too and interesting that it survives. I wonder if it it was a school or to do with the pumping station, its close and on the map looks adjacent, the brickwork looks very similar and quite ornate like the block that survives

I had a look on google maps and it does look to be part of the original pump house complex, a caretaker or gate keeper accommodation as was quite usual back in the day

I had a look on google maps and it does look like part of the same original complex. A gatekeeper, caretaker,security, accommodation a was quite usual back in the day

I just looked on google maps and it looks to be part of the same complex. Accommodation for a caretaker, gatekeeper,security which was quite common back in the day.

The hydraulic water power was still in use in the early 1970s to power the lifts in several Mansion blocks of flats in Central London. Amongst others Oxford and Cambridge Mansions in Marylebone Road near Edgware Road station. It had formerly been used in Burleigh Mansions in Saint Martin’s Lane

Another brilliant post

Well done

Understand the prospect of Whitby was named after a ship that used to moor almost opposite the old pub

My family lived in Milk Yard just down the road from the Prospect of Whitby. They were there for nearly 80 years and they worked as dock labourers and some of my great uncles as lightermen.

I have 2 wonderful photographs of my grandmother and her 2 sisters working at the London Hydraulic Company. I assume from the pictures that it was around the time of the 1st world war and the pictures show them shovelling coal.

It’s a shame I can’t attach the pictures to these comments.

Just thought you should know there is another website called a London Inheritance. No doubt a Johnny come lately. Trying to attach a screenshot of it . Not sure if I’ll be able to . No it didn’t work. If you email me I’ll see if I can send it. Guess th3 Internet doesn’t believe in copyright.