After a strange and tragic year, a year in which so many have suffered loss of loved ones, financial loss and the day to day stress of living through a pandemic, I thought I would end 2020 with a rather different post. One that looks back on the blogs and books I have been reading during the past ten months, and looks at how previous population trends across London may change in the future.

Three very different subjects, but hopefully suited for the period between Christmas and the New Year, when the days lack their normal structure and blend into each other, made even worse with the restrictions of Tier 4, and when the change to a new year brings thoughts of the past and the future.

Blogs

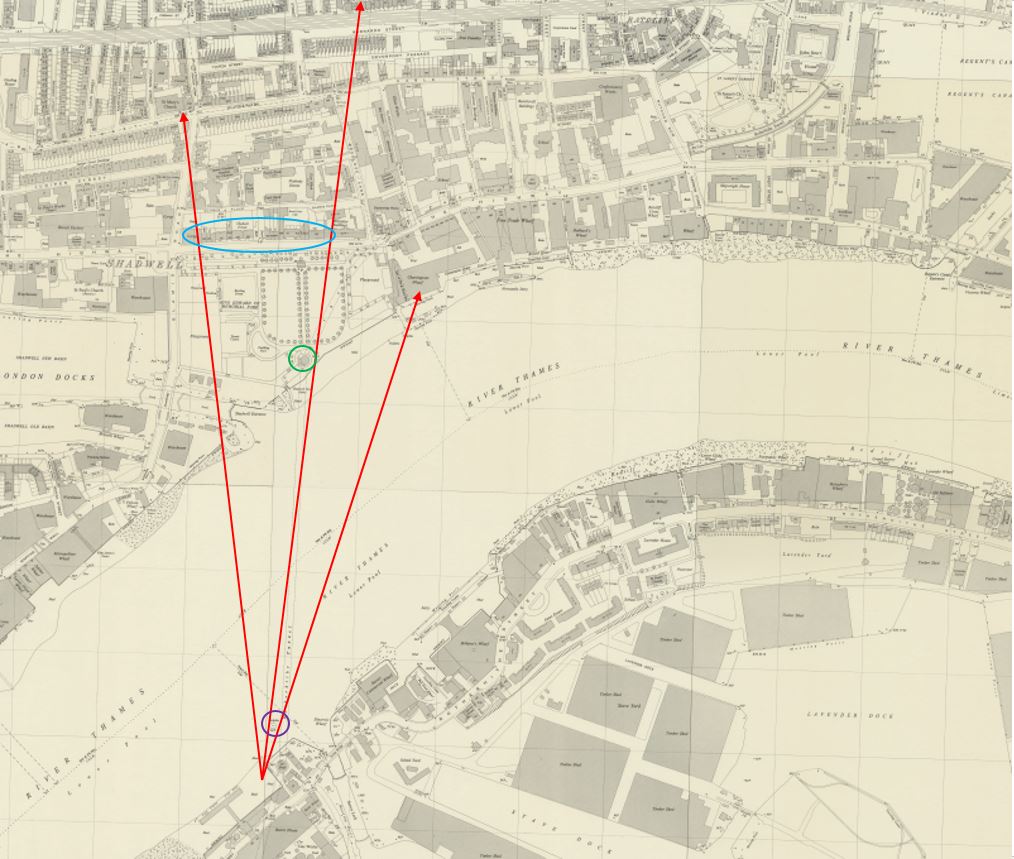

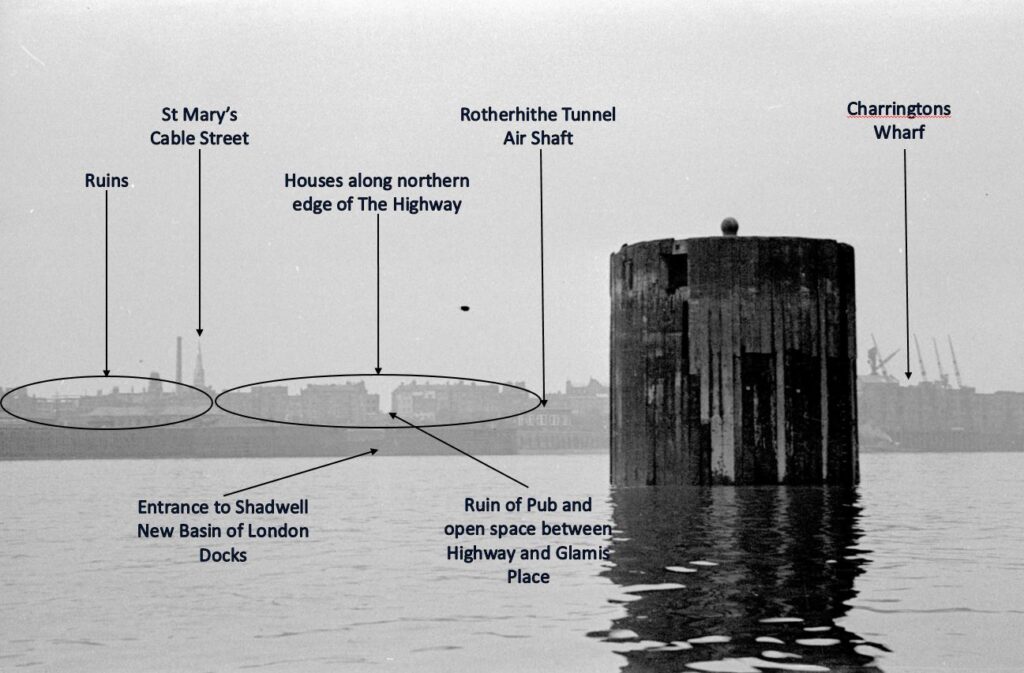

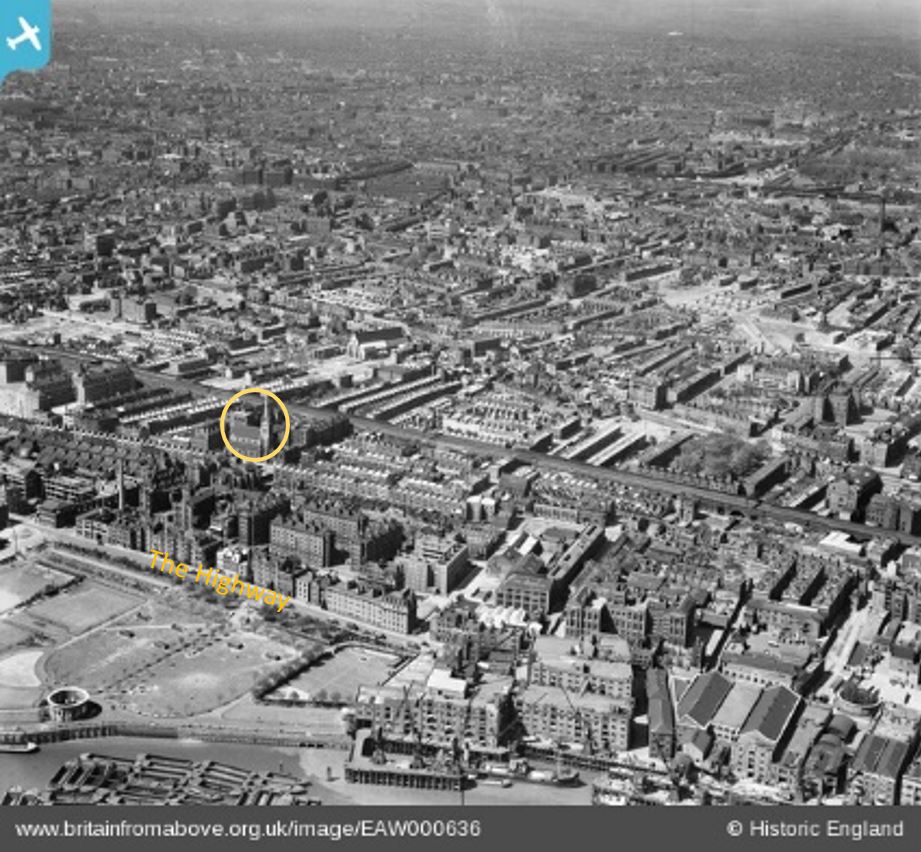

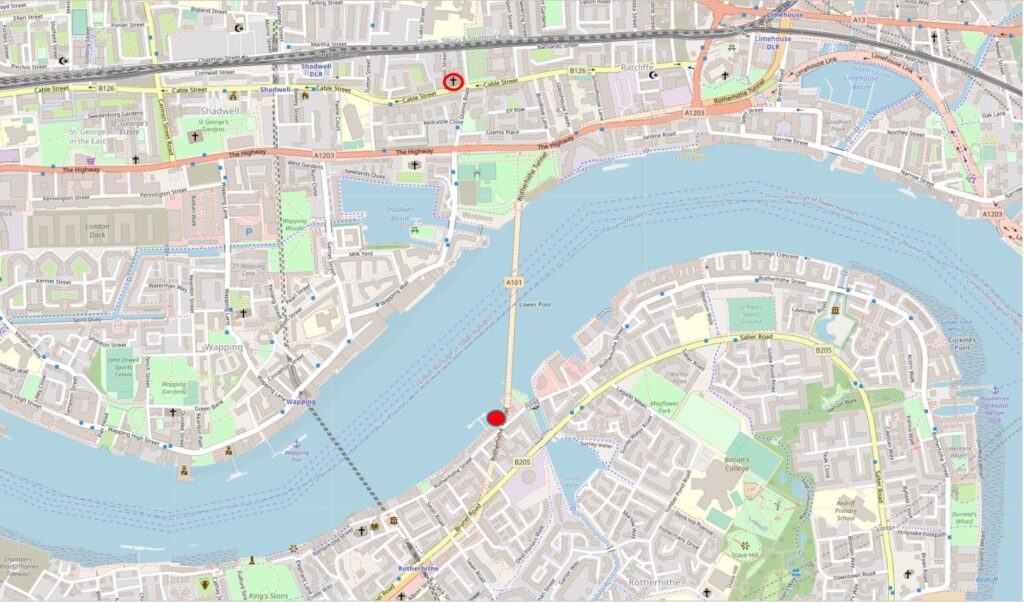

I started writing the blog back in 2014 after attending a blog writing course run by the Gentle Author of Spitalfields Life. I had been trying to summon the motivation, and a purpose for a project I had been thinking about for years, to track down the location of the sites my father had been photographing from 1946.

It seemed the structure and routine of a blog would provide the right motivation and purpose, although I did not expect to be still writing almost seven years later.

One of the blogs I have been reading for years is Diamond Geezer, who has been writing since 2002 and publishes daily. One of the topics Diamond Geezer occasionally touches on is the loss of many long form blogs, and whether this form of writing is a gradually disappearing format.

I hope not given that I probably started rather late using blogging as a medium, so I thought I would celebrate the diversity of blogs with a sample of those that I read regularly. I will also be adding what WordPress terms a Blogroll to the side bar of the blogs main page.

So starting with the blog that started me writing:

Spitalfields Life – A blog that probably needs no introduction from me. Written by the Gentle Author, a daily exploration of the people and places of east London, and indeed London as a whole. Spitalfields Life has become a campaigning blog, addressing some of the proposals that seem to want to change London without considering the history or future of the city, probably apart from a quick commercial return.

Diamond Geezer – Another blog that posts daily, with the added benefit that you are never sure what the topic will be. Covering London, as well as visits to the rest of the country, analysis of data published about London’s transport network, anniversaries, street names etc.

What I envy about the Diamond Geezer blog is the ability of the author to craft a wonderful 50 words on a topic, where I would waffle through 500 words trying to say the same thing.

Bug Woman – Adventures in London – Mainly focused on the flora and fauna of London, Bug Woman shows another side of the city. The animals, plants, trees that are around us, but need that extra bit of attention to see and understand.

Bug Woman started with a weekly post, but for the last few months has been posting daily and provides a fascinating alternative view of the city.

Flickering Lamps – Although posts from this blog are not frequent, what the blog lacks in quantity is easily covered by the quality of the posts. A historical blog which brings to life some unique stories with in depth research and some wonderful writing and photography. A blog which demonstrates how much there is to be discovered across the streets of London, and further afield exploring the churches, graves and ruins to be found across the country.

Nature Girl, or “nature writing from a country warden” – I found this blog when I was researching a visit to the London Stone by Yantlet Creek on the Isle of Grain. The author is an Environmental Consultant in that wonderful area of Kent along the River Thames and inland to the River Medway. Although the blog is not about London, the proximity and influence of the Thames on north Kent has always fascinated me, and London looms as a potential threat to the area from expansion of the city, schemes such as the estuary airport, housing development, energy projects etc.

Nature Girl writes about the natural beauty of the area, and the importance of looking after such a special area of the country, not that far out from London.

Historic Southampton – Southampton is a city that like London was badly bombed in the last war, grew significantly because of the city’s access to the sea, and has a long and continuing history as a major port. The Historic Southampton blog explores the history of this fascinating city, and through some unique research and presentation of data, has mapped the location of Titanic crew members who lived or lodged in the city, and really brings home the impact of the disaster on the families in just one city.

The above is just a sample, there is so much creativity and research to be found across the blogging world, and hopefully the format will continue to gain an audience for many years to come.

London 2020 Reading

I have probably read more during 2020 than in any previous year. I have also tried to expand my London reading to explore recent history, and the London that I have experienced from the mid 1970s. The following books are a sample of my 2020 London reading (over the years, I have been offered books to review, I never except these. All books have been chosen and purchased by me, usually in a bricks and mortar book shop. It is very important to me to keep the blog free of any external, commercial or hidden influence):

London Made Us – Robert Elms

Robert Elms is a broadcaster on BBC Radio London, a writer and once a journalist with the New Musical Express (NME). The title London Made Us very much describes the contents of the book – a family history of London, growing up in London and how London has changed.

I will use the word evocative a number of times in the rest of the blog, and for London Made Us, the book is brilliantly evocative of London in the 1970s and 80s.

Elms supports Queens Park Rangers, who play at Loftus Road. I have a very different experience of Loftus Road, it was where I saw my first major stadium concert in 1975 when Yes were headlining – a memorable day which still seems as if it was only yesterday.

Alpha City – Rowland Atkinson

One of the reasons that London has such a global presence is the attraction of the city to the super-rich of the world.

The attraction of London as an asset rich city, a place where wealth can be accumulated and preserved has an impact on all those who live and work in the city. This has influenced the buildings we see grow across the city, the ownership of the city’s land and buildings, on the type and price of housing across the city.

Alpha City helps explain why London is the London we see today, and what the impact of these trends will be on the future of London and in-equality in the city, and goes some way to explaining why the population density of Kensington & Chelsea has reduced so significantly (see later in this post).

Soho. A Guide to Soho’s History, Architecture and People – Dan Cruickshank

This is a wonderful book on a unique area of London. The first half provides historical background, the initial development of the estates that would come to form Soho and some social history of the area.

The second half is titled The Walk and presents a detailed walk through Soho, street by street and frequently house by house. I read the first half at home, then took the book out and followed the walk.

Soho is at risk of the type of development that will gradually erase what makes Soho a defined area in the city with its own unique character. Books like Cruickshank’s will help prevent this, or will help provide a record of a unique place for the future.

On The Marshes – Carol Donaldson

Carol Donaldson is the author of the Nature Girl blog mentioned above, and I purchased the book after reading the blog.

On The Marshes is a record of a journey across north Kent from Gravesend to Whistable whilst coming to terms with the break-up of a long-term relationship.

On the Marshes provides a wonderfully evocative view of the north Kent marshes and rivers, and covers aspects such as the plotland developments – plots purchased by individuals, frequently those escaping London, who built their own home and lived based on what they could find around them.

A good read to really understand this area, and then get out for some walking.

Excellent Essex – Gillian Darley

Again, not a London book, but a book which tells the story of a county that borders, and has been influenced by London. A county that has lost many of its original south western towns, villages and lands into Greater London.

The Essex coast has been a holiday destination for Londoners (Southend and Clacton), where many Londoners moved after the war, to new towns such as Basildon, and a county that has a long relationship with the River Thames and North Sea.

The book’s sub-title is “In Praise Of England’s Most Misunderstood County” which is a good summary. Essex has long been the focus of jokes about Essex Girls, Brentwood was a lovely country town on the main A12 into London before TOWIE gave the town a different reputation.

Basildon was one of the key constituencies that signaled the swing to Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives in 1979, and became known for “Mondeo Man”.

Although these are the aspects of Essex that are frequently in the media, there is far more to Essex. Travel to the north of the county and it is a very different place to the south and Excellent Essex takes the reader through the whole history and geography of the county of Essex.

Some Fantastic Place – Chris Difford

Chris Difford was, along with Glenn Tilbrook, one of the original founders of the band Squeeze, and has been responsible for the majority of their lyrics.

Squeeze has long been one of my favourite bands and whenever I hear the opening of Take Me I’m Yours, I am transported back to driving around in my first car with their music playing on an Amstrad car cassette player.

Chris Difford grew up in Greenwich and his dad worked at the gas works on the Greenwich Peninsula. The book is an evocative story of growing up in Greenwich, and starting a band in Greenwich, Blackheath and Deptford. The book also touches on the London music industry, Bryan Ferry and Elvis Costello.

A brilliant read about growing up in south London, and a life in the music industry.

Defying Gravity, Jordan’s Story

The book is about Pamela Rooke, or Jordan as she was known as the face of Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s shop SEX at 430 King’s Road. later known as Seditionaries.

Jordan was there at the start of Punk in London, and if what punk was intended to be could be summarised by one single person, then it was probably Jordan.

Jordan played the part of Amyl Nitrate in Derek jarman’s 1978 film Jubilee, a film that portrayed Jarman’s view of punk, and England in the years around the 1977 Royal Jubilee, when Queen Elizabeth I is transported to London to see the decline of the country in the late 1970s. The film is great for a bit of location spotting as it was filmed at many locations around London, including Shad Thames, where Jarman had a studio at Butler’s Wharf.

The book is a brilliant read and brings to life not only Jordan’s story, but also that unique time when punk, music and fashion converged, against the backdrop of a London about to go through a period of considerable change.

Changes in London’s Population

This year there have been many stories in the media about people moving out of London. The growth in working from home enabled by the ability to work from anywhere with an Internet connection, with many companies seeming to accept that a high degree of home working will become normal in the future.

This has been a rapid acceleration of an existing trend and it will be interesting to see what impact it has on the need for office space, London housing and London’s population in the coming years.

Up until the start of the year, London gave all the impressions of a very busy city. Streets full of people, crowded underground trains where frequently standing was the only option, the West End teeming with people in the evenings, busy cafes, restaurants and pubs.

Lock downs have had a catastrophic impact on so many London businesses in the entertainment and service industries. Add to this the collapse of tourism, and London feels a very different place to this time last year.

Although up until the start of the year, London felt very crowded, in reality London’s population was only catching up to levels last seen at the start of the 1960s.

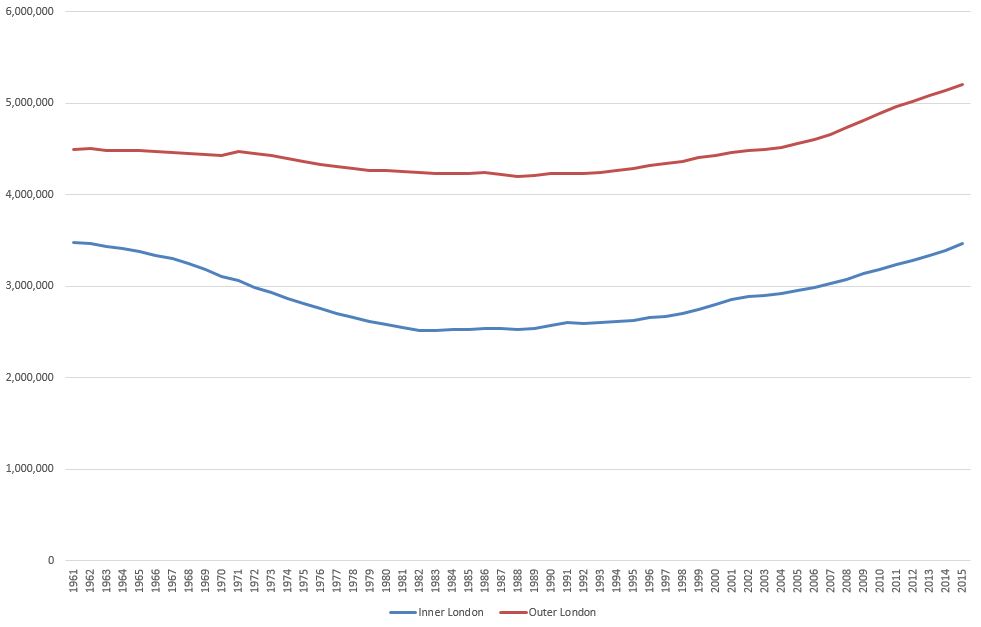

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) publish some fascinating data, and I was recently browsing through some London population data (to pinch the words of Rowan Atkinson in Blackadder – the long winter nights must just fly by), and converting the data to graphs as I find it much easier to see trends using graphical presentation.

The following graph shows population numbers for inner (blue line) and outer (red line) London from 1961 to 2015.

The graph shows that for inner London there was a fall in population of almost 1 million from 1961 (3.481 million) to 1983 (2.517 million), a fall of around 27%.

The fall across outer London was less dramatic, declining from 4.496 million to 4.202 million in 1988.

A number of factors contributed to such a significant decline across inner London, including:

- slow rebuild of housing lost during the war

- closure of industry, and the move of industry outside of inner London

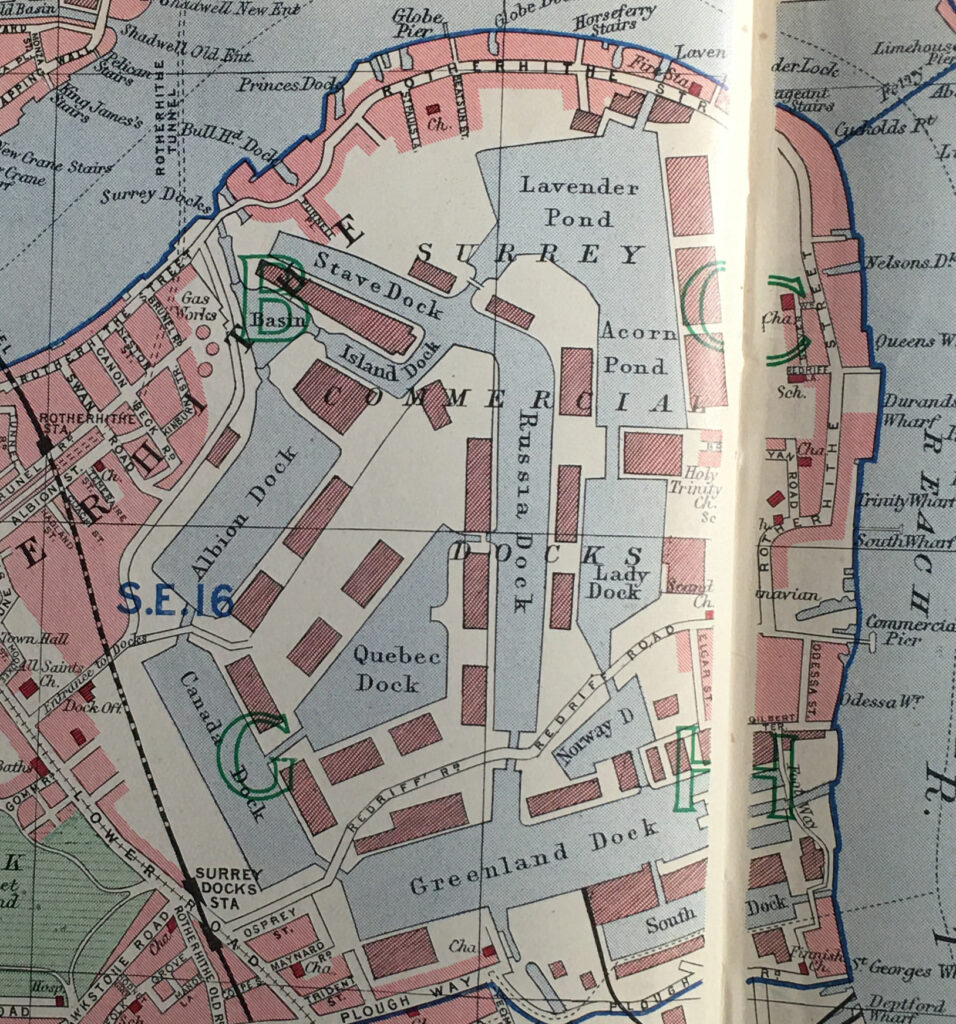

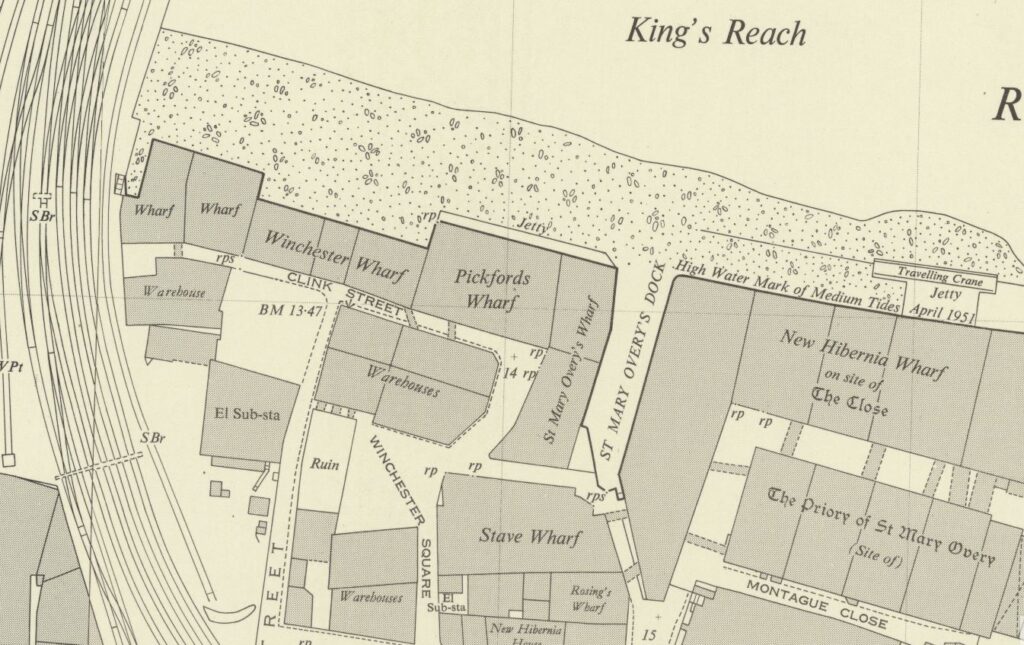

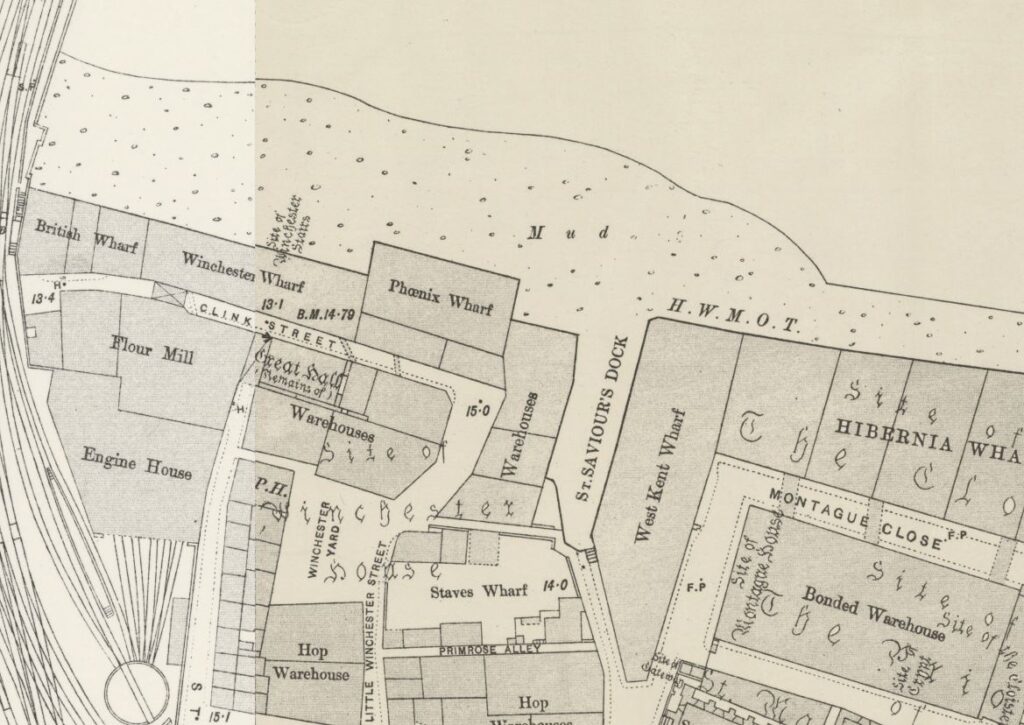

- slow down in trade on the Thames, containerisation and eventual closure of the inner docks

- migration to new towns such as Harlow and Basildon

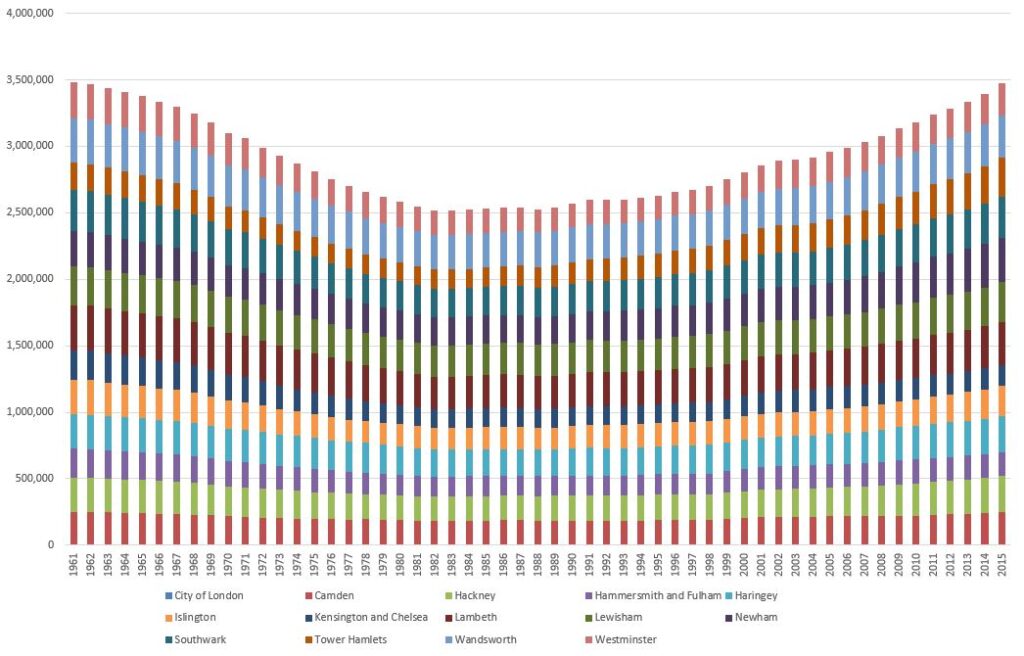

We can see the areas included in the ONS definition of inner London, as well as their individual population movements by graphing each individual area over time as shown in the following graph.

Inner London Population – 1961 to 2015

The City of London should be at the bottom of each column, however the population of the City is so low compared to the rest of inner London that it is does not show based on the vertical population scale. The population of the City changed from 5,000 in 1961 to 8,760 in 2015, with a low of 4,000 for most of the 1960s.

Whilst many areas of inner London returned to a similar population in 2015 that they had in 1961, there are some variations.

The populations of Hammersmith & Fulham and Kensington & Chelsea are still below their 1961 levels. Tower Hamlets and Newham are both above their 1961 levels.

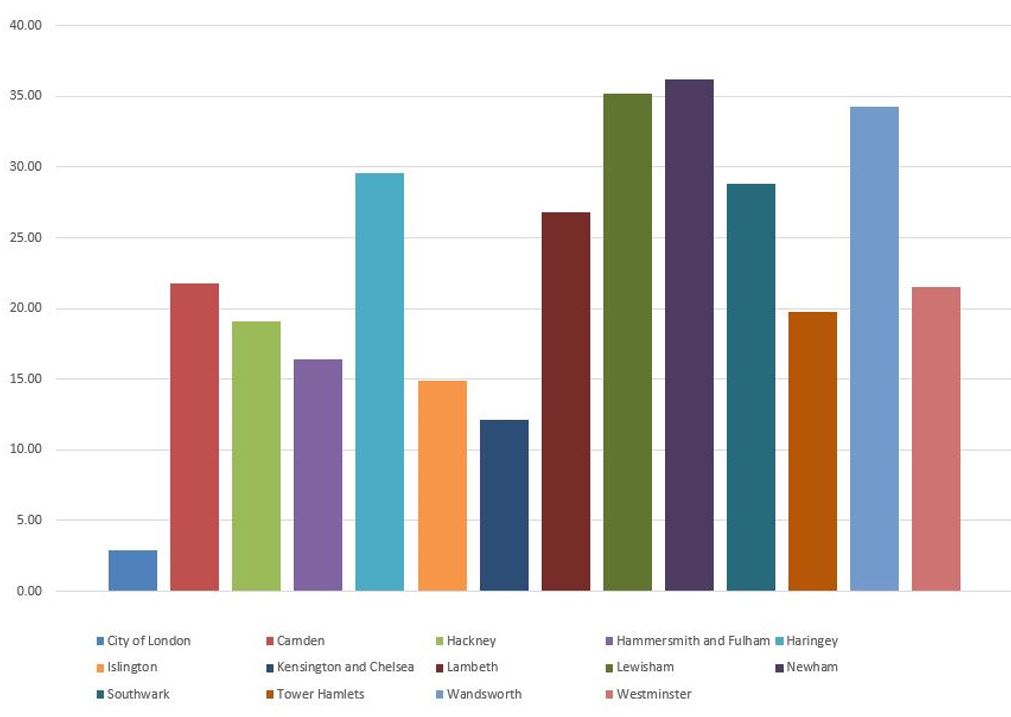

One of the reasons that the population of the City is so low, as well as the City being mainly a business area, it is also the smallest of the areas classed as inner London. The following graph shows the area in square kilometers for each area of inner London.

Inner London – Size of each Borough in 2016

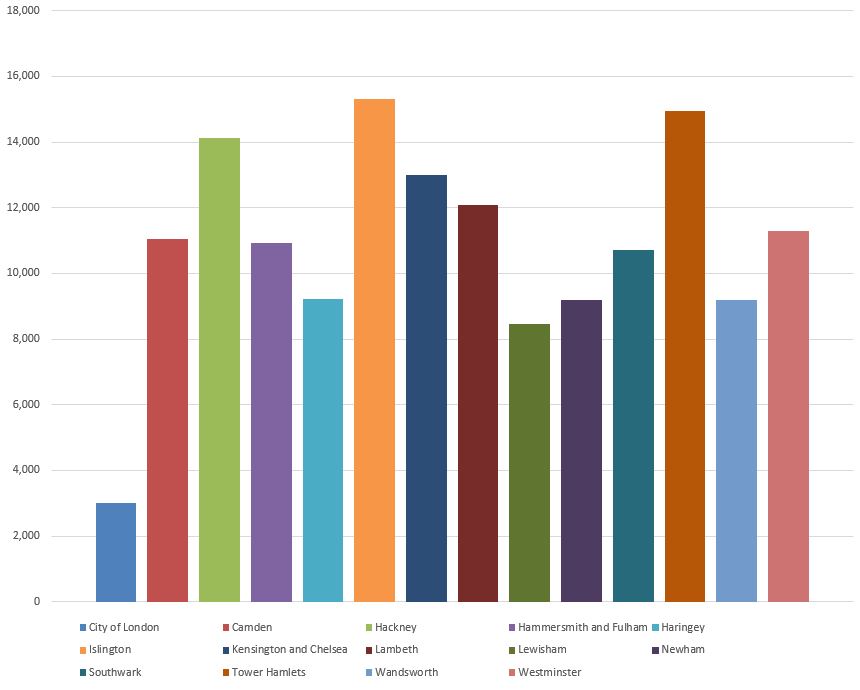

By comparing the population with the area, we can see the population density of each area of inner London, as shown in the following graph which illustrates the number of people per square kilometer.

Inner London – Population Density in 2015

In inner London in 2015, Islington was the most densely populated area, with Tower Hamlets not far behind.

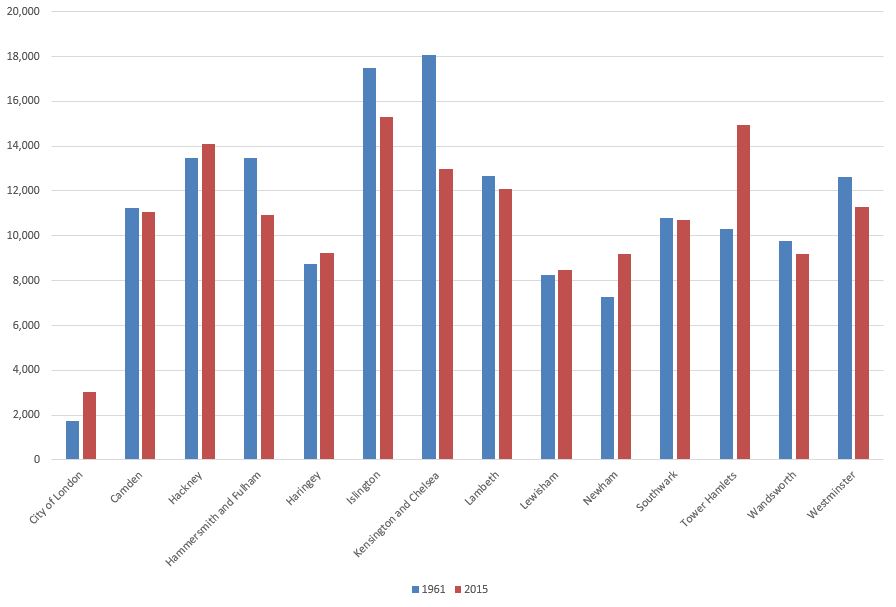

Inner London – Changes in Population Density between 1961 and 2015

What is really interesting is to compare the change in population density for each area of inner London between 1961 and 2015, as shown in the following graph where the blue column represents people per square kilometer in 1961 and the brown column represents 2015.

Islington, whilst being the most densely populated borough in 2015, was more densely populated in 1961.

The highest reduction is in Kensington & Chelsea, which in 1961 was the most densely populated borough, but this had reduced considerably by 2015. Possibly a result of housing policy in the borough, changes in multiple occupancy, housing treated as an investment rather than a home and often left empty etc.

The borough which has increased population density the most is Tower Hamlets. Possibly due to reconstruction after the war, land once occupied by industry and docks now occupied by housing, and that east London has long been the traditional initial destination for immigration into London.

Whilst the population of outer London reduced after 1961, it did to a much smaller degree than inner London, reflecting the different industrial and commercial mix in inner than outer London, as well as a gradual move of population from inner to outer London.

What is marked is the increase in the population of outer London, so that whilst inner London had recovered to 1961 levels by 2015, outer London has seen an increase of over 700,000.

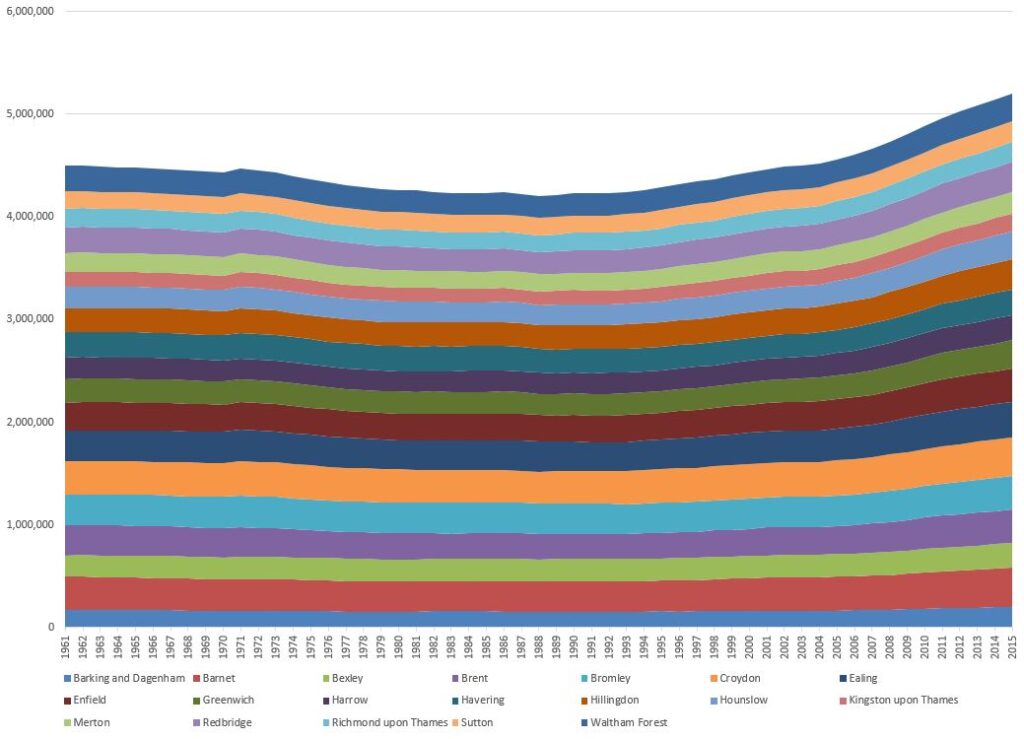

The following graph shows the population changes in outer London from 1961 to 2015.

Outer London Population – 1961 to 2015

As with inner London, the geographic size of the outer London boroughs varies considerably with Bromley being by far the largest. This does not mean that population size follows geographic size as Bromley has a similar population to the much smaller Ealing.

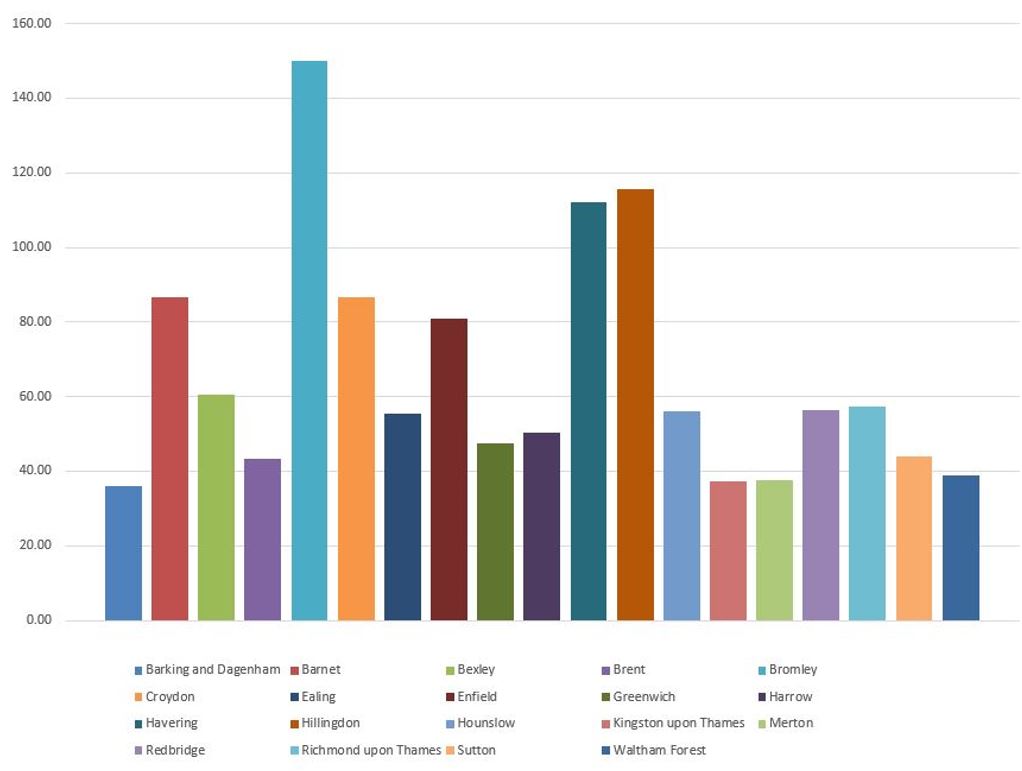

The following graph compare the size of each outer London borough (in square kilometers):

Outer London – Size of each Borough in 2016

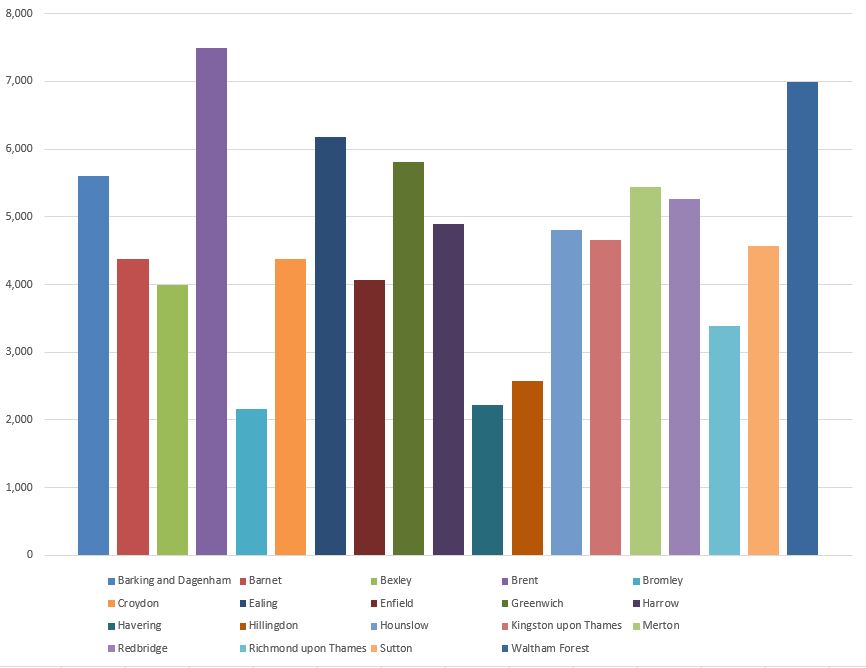

We can compare population density in the following graph, which charts the number of people per square kilometer for each borough.

Outer London – Population Density in 2015

Compare the above two graphs. Bromley is by far the largest in land area, but the smaller when defined by population density. Brent has the highest population density with almost 7,500 people per square kilometer.

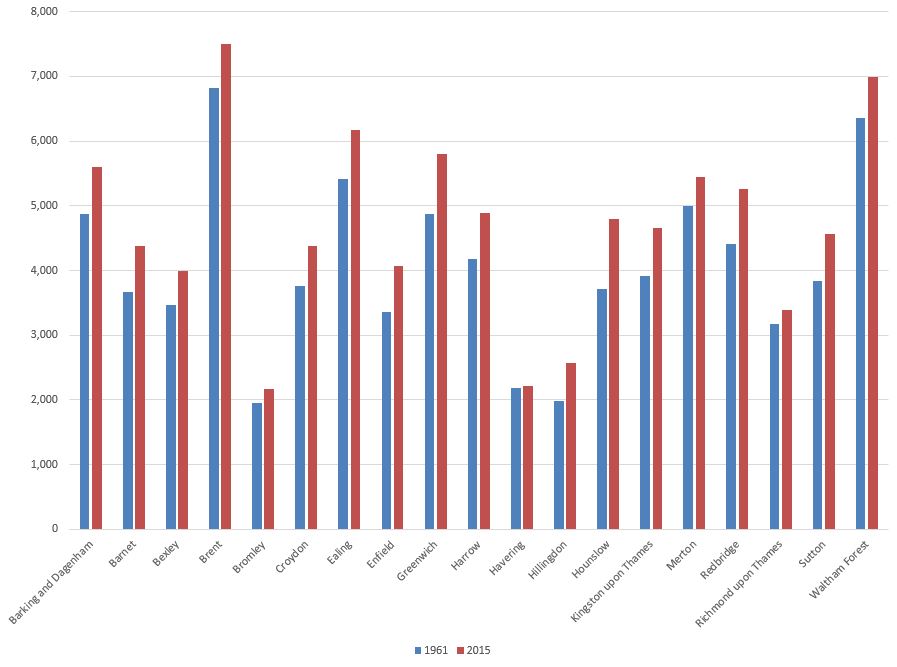

The following graph compares population density of the outer London boroughs in 1961 (blue column) with 2015 (brown column).

Where a number of inner London boroughs population density has reduced from 1961 to 2015, all outer London boroughs have increased their population density, reflecting a migration of people from inner to outer London, and perhaps those moving to London preferring to live in the outer rather than the inner London boroughs.

The cost of housing will also drive this change with housing costing slightly less the further from the centre of the city (although still very expensive).

All the above ONS data is from 2015. Numbers have almost certainly increased since then, and it will be interesting to see what happens in the coming years.

Will changes to working patterns influence where people want to live, and will the loss of jobs in the entertainment and service industries result in a long term contraction, or will coffee shops, restaurants, bars and shops return to their former numbers.

Will Brexit have any impact on the businesses that make London their base?

The themes of today’s post may be very different, but they are really about the same thing – exploring and recording how London changes, and the individual experiences of those who come into contact with the city. Whether that is through a long life in the city, having been part of a key period of London’s cultural life, or being part of the counties surrounding London. Individual experiences recorded in a blog or book, or the experience of large populations recorded in the ONS data.

Can I wish all readers a very happy New Year, and hopefully 2021 will turn out to be much better than 2020 and London returns to being the busy, dynamic and diverse city that makes it in my totally unbiased view, the best city in the world.