I have featured a couple of the sites from Hugh Pearman’s 1951 book Curious London in previous posts, XX Place and Goodwin’s Court, however these were individual places, so I thought I would take one of London’s “villages” as defined by Pearman and visit all six of the locations mentioned (if they still exist). I picked Southwark as I want to explore more of south London this year, so here is Curious Southwark.

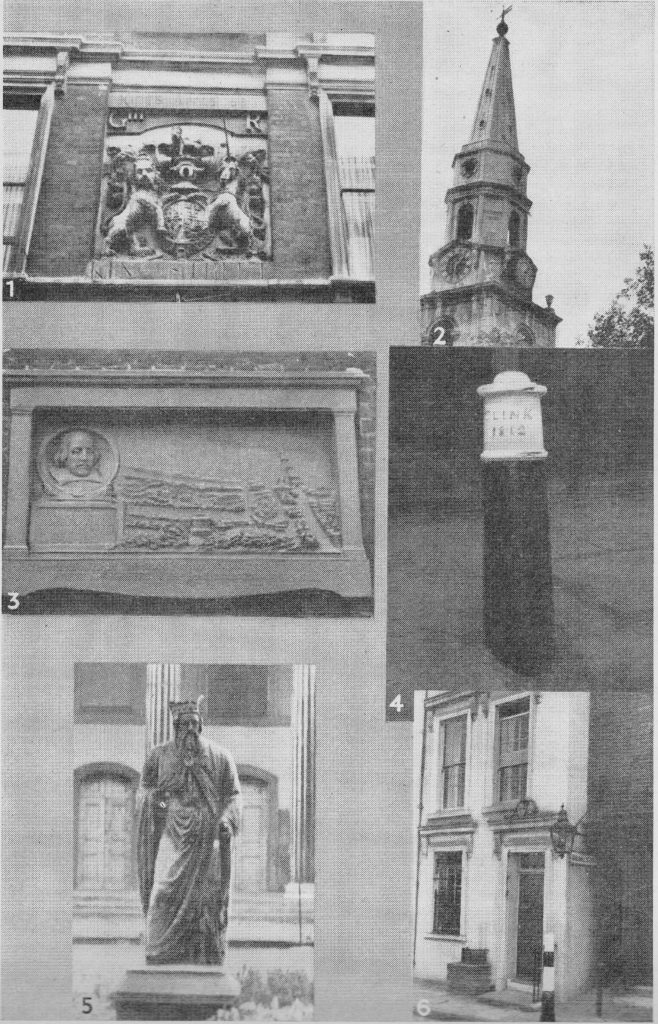

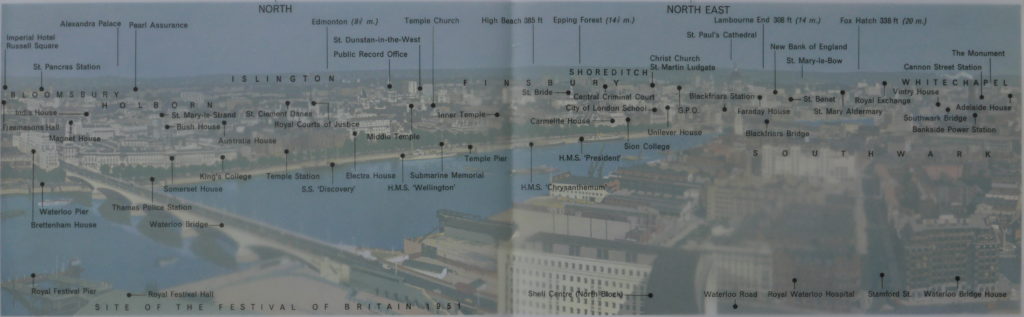

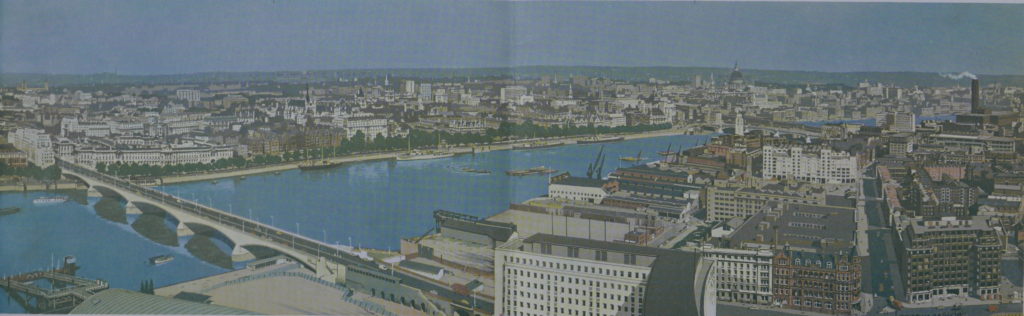

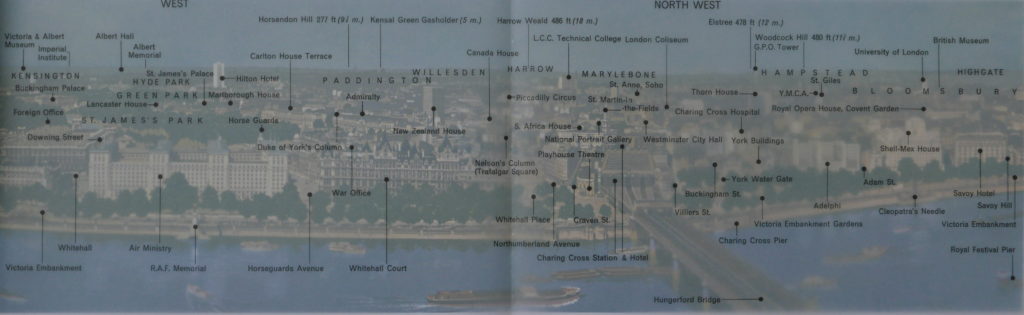

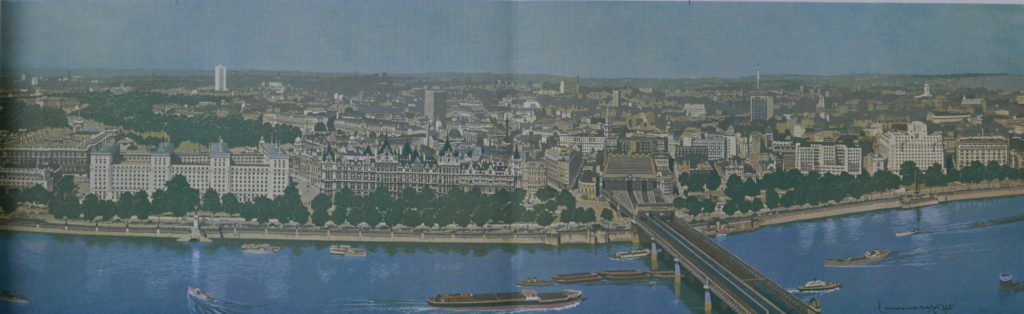

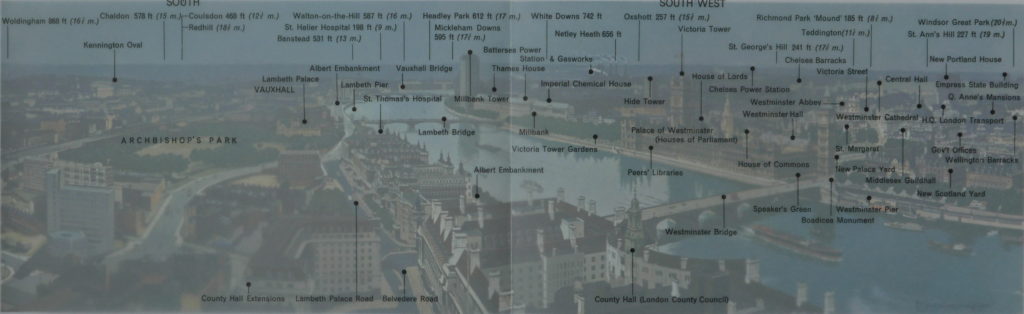

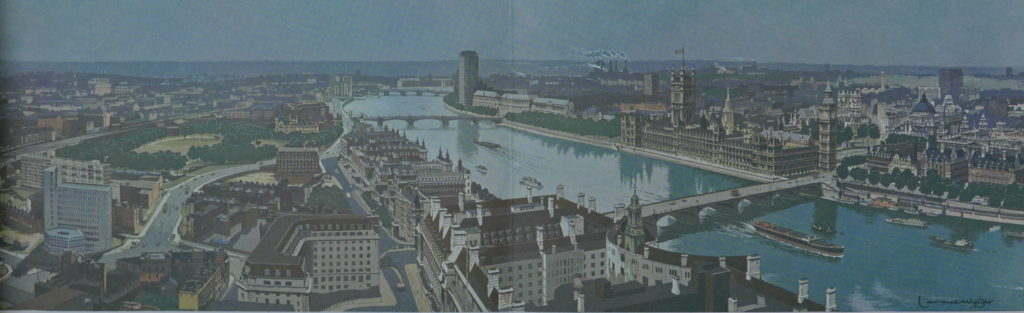

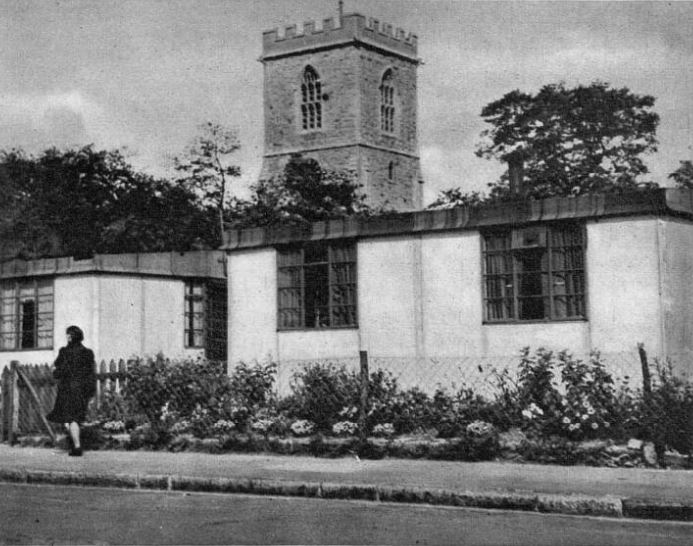

The photograph page from the two pages on Southwark in Curious London.

From 1 to 6 they are:

- A pub in Newcomen Street

- The clocks on the church of St. George

- Shakespeare’s Globe

- Clink bollards

- The oldest outdoor statue in London

- Cardinal Cap Alley

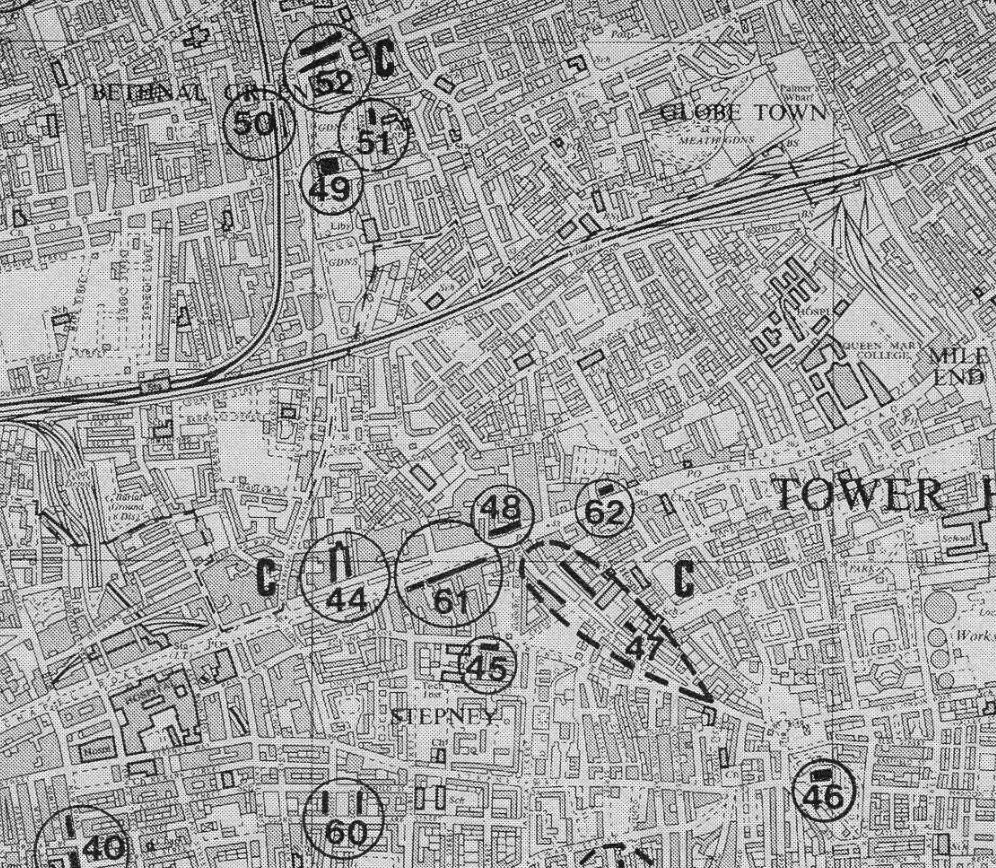

I walked the sites covered by Pearman in a different order to the way he had numbered in the book. I started at the location furthest to the south and walked back towards the river, stopping at the sites as I came to them. The following map shows the locations, with my numbering to reflect the order in which I visited each site.

Starting at site number one to find:

King Alfred and Trinity Square

“The oldest outdoor statue in London is this one of King Alfred. Dating from 1395 it stands in front of Holy Trinity Church, Trinity Square. Originally standing in a niche on the outside of Westminster Hall, it was removed to its present site in 1821.”

So wrote Hugh Pearman to describe the statue in front of Holy Trinity Church and which led me to point 1 on the map where I discovered a magnificent church, one I had not walked past before, so for me, a new discovery.

The statue that Pearman refers to is in the middle of the garden in front of the church.

But is this King Alfred and is it really the oldest outdoor statue in London?

The church dates from 1824 (year of consecration), and there are two main theories as to the original source of the statue which appeared in front of the church when the gardens were being laid out in the 1820s.

The first theory is that the statue is one of eight medieval statues that were originally located on the towers at the north end of Westminster Hall. Five of these disappeared when Sir John Soane was re-working the front of the hall in the same years as the church was being built.

The second theory is that the statue was one of a pair made for the gardens of Carlton House by the sculptor John Michael Rysbrack in 1735. Carlton House was demolished in the late 1820s, again in the same decade as the construction of the church and the creation of the gardens.

The statue also appears to have had some extensive restoration, probably using Coade stone.

I suspect we will never know which of the two theories is correct.

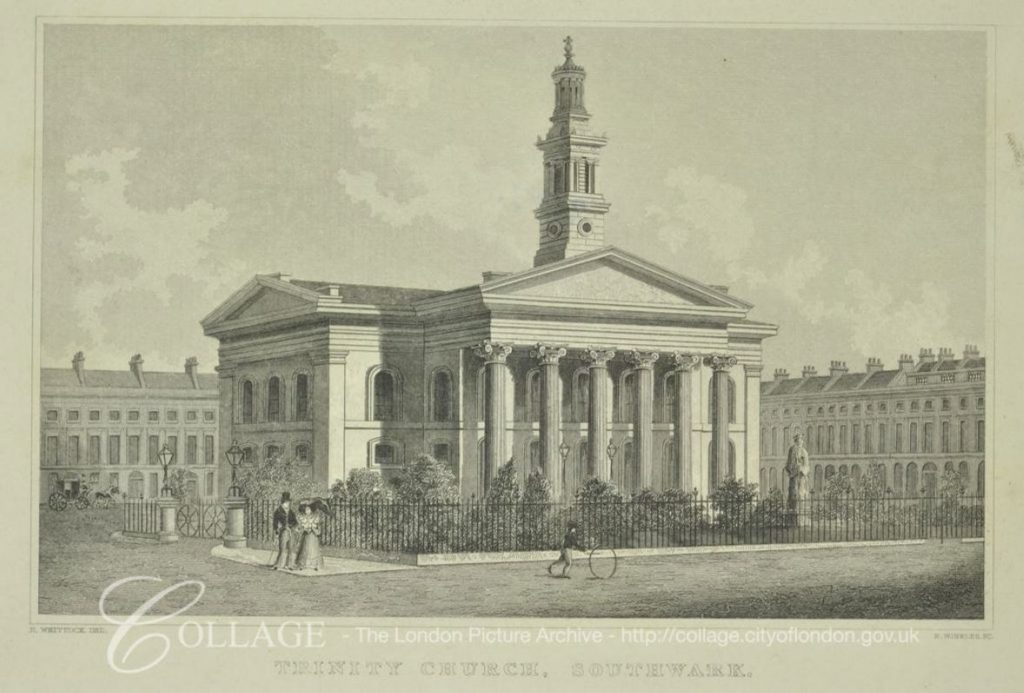

This print from 1830 shows the statue in place in front of the church.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: 306294

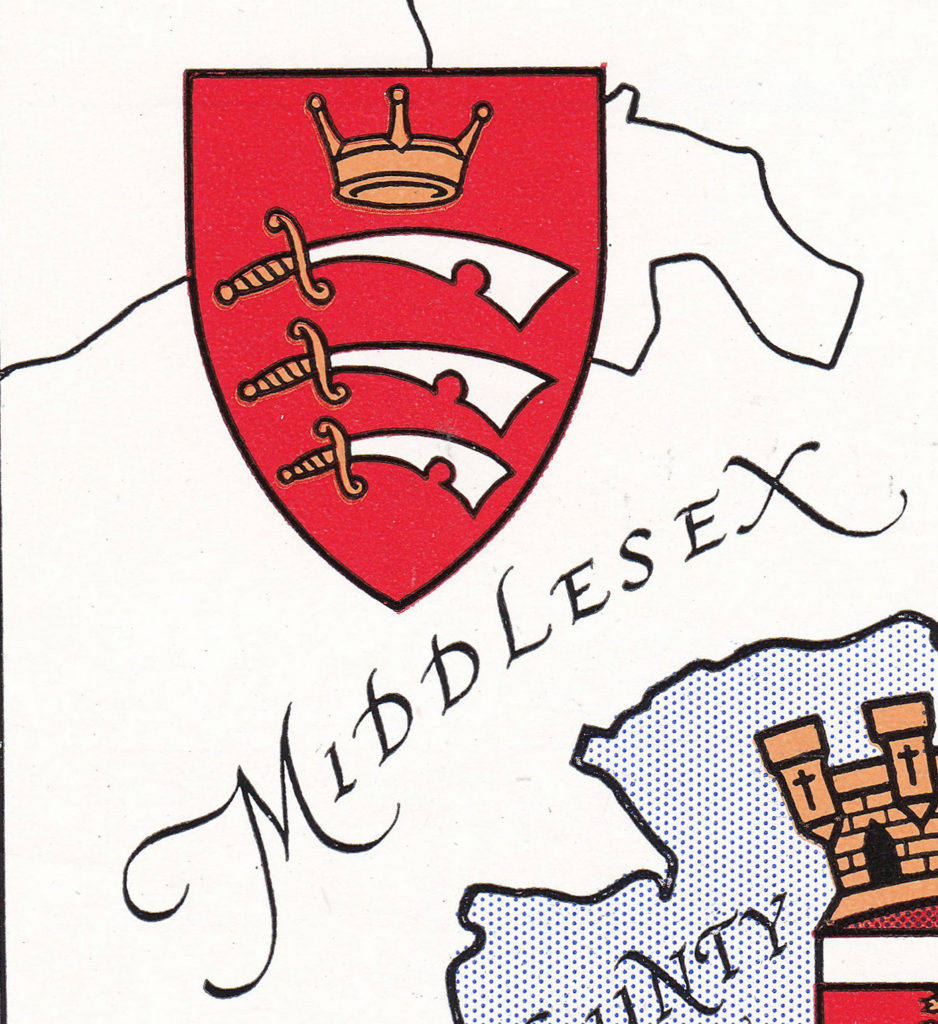

The church and surrounding streets are rather unique, both architecturally and in their ownership. The area is known as Trinity Village and is on land that originally formed the Newington Estate, owned by Christopher Merrick, who gave the land to the Corporation of Trinity House in 1660.

The estate was originally mainly used for commercial activities, however in the early 19th century the development of an estate with housing following a Georgian design commenced.

Trinity Church was part of the development, with the square that surrounds the church along with several streets that comprise the overall estate.

Trinity Church became redundant as a church in the early 1960s. In the early 1970s the London Philharmonic and London Symphony Orchestras were looking for new rehearsal space in London and commissioned a review to look for a suitable location among the redundant churches across London.

Trinity Church was identified as a suitable candidate which was confirmed in December 1972 when test rehearsals were held in the church. The buildings and land were purchased from the Church in 1973 and returned to the Corporation of Trinity House.

An extensive restoration of the church was then carried out and on the 16th of June 1975 the church was formally opened as rehearsal rooms and named the Henry Wood Hall with a concert by the London Philharmonic and London Symphony Orchestras. The name is after Henry Wood, who was associated with the Proms for almost 50 years and after a substantial donation from the Henry Wood fund to the restoration of the building.

The estate continues to be owned by the charitable arm of the Corporation of Trinity House with all rents being received by the charity.

The surrounding streets are magnificent and the following photos are from a walk around the square that surrounds the church:

The square is very peaceful. I walked round the square in the centre of the road to take photos and did not once have to move for a car.

One side of the square shows how close this unique part of Southwark is to London Bridge.

A final view of the church as I set off for the next location:

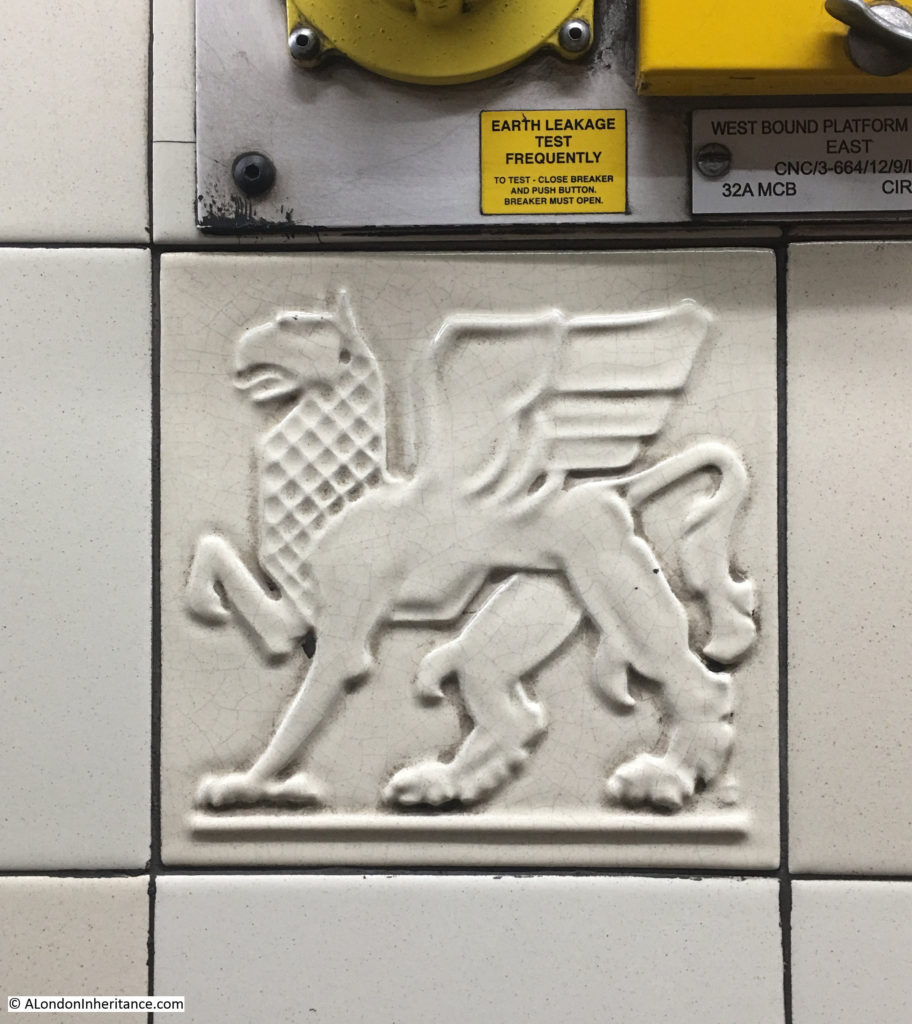

And here I found at the side of the street the Coat of Arms for Trinity House. dated 1883:

Whatever the truth of the origin of the statue, I was pleased that looking for the statue took me to a fascinating part of Southwark that I had not seen before.

It was then a short walk to point 2 on the map:

St George the Martyr, Borough High Street

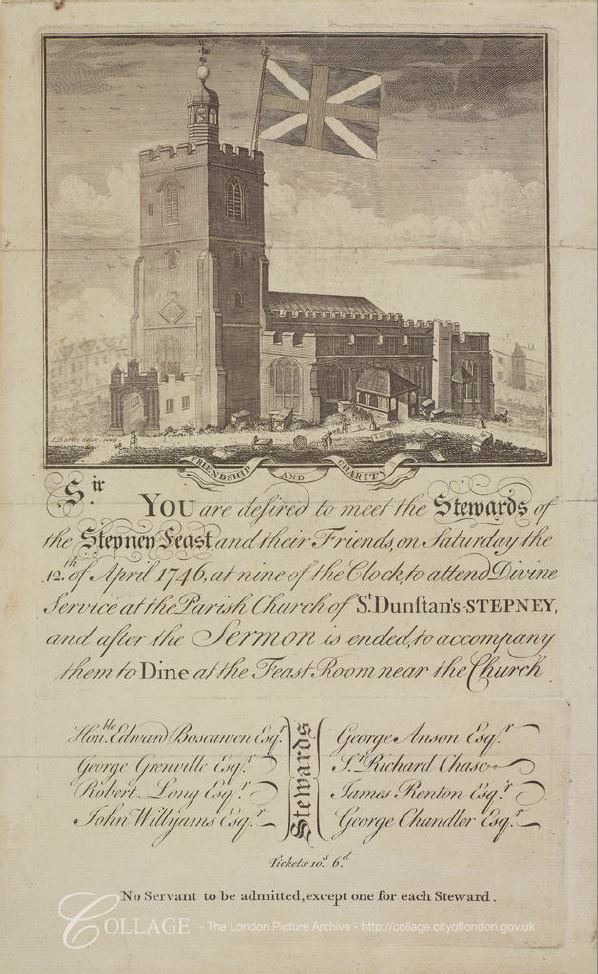

“Local tradition says that because of the meanness of Bermondsey people when an appeal was made for funds to erect the clock tower of St. George’s Borough High Street, the face of the clock looking towards Bermondsey has always been painted black.”

When I reached the church of St. George I was disappointed to find that the body of the church was surrounded by scaffolding and plastic sheeting, but relieved that the tower was still fully visible so I could confirm Pearman’s statement about the clock.

Three sides of the church have the same clock faces which presumably have internal lighting and are therefore visible at night.

But the fourth clock face is very different.

This clock is over the main body of the church and is indeed facing in the general direction of Bermondsey, however you would need good eyesight to see the clock from Bermondsey and presumably not be at street level as the tower would have been obscured at that distance by buildings.

There are very many references to the same story as told by Pearman.

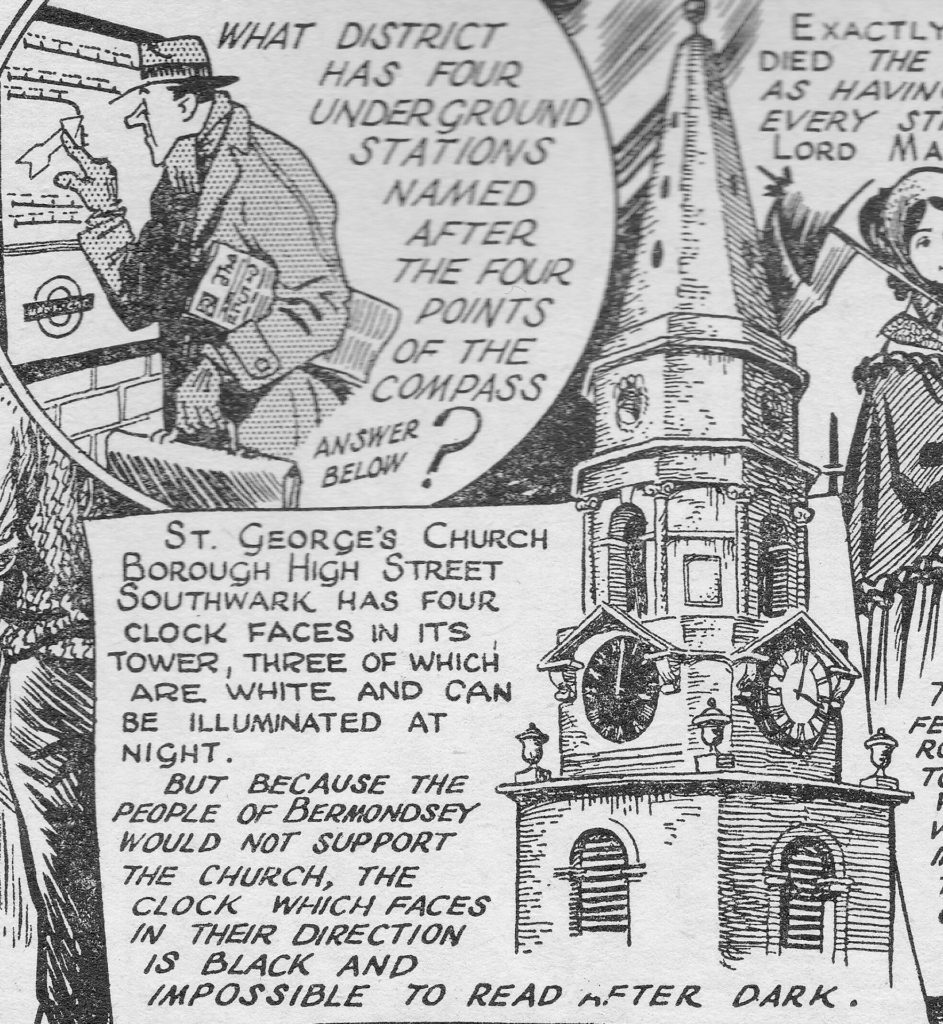

My father bought a book titled “London is stranger than fiction” by Peter Jackson in 1951. Jackson was an artist who started producing cartoons detailing London’s history in 1949 in the Evening News. He would continue until the paper closed in 1980.

There was a second book of his cartoons published later and I managed to buy a copy of this second book a couple of years ago.

In the first book, there is a mention of the clocks at St. George’s in the cartoon strip that appeared in the 28th December 1949:

The current clock dates from 1868 although with post war repairs due to the considerable damage suffered by the church during the war.

Three of the clock faces were lit by gas. The church’s website states that the fourth clock face was not lit due to the cost, and also relates the story of the residents of Bermondsey, but as an apocryphal story rather than a statement of fact.

The unlit clock is above the main body of the church and so not easy to see from many angles, whilst the three other clocks are all obscured so I can understand that from a cost perspective, lighting the three fully visible clocks was more important than lighting the fourth – but again, I suspect we will never know the true story.

Although the church is currently covered in plastic sheeting, the interior of the church is well worth a visit.

A church may have been on the site since the 12th century, however the current church dates from 1736, although the interior of the church has undergone many changes, including the restoration needed following severe bomb damage in the war. A number of high explosive bombs landed very close to the church and a V1 flying bomb hit a short distance down Borough High Street.

An archaeological dig in the crypt of the church found evidence of possible burials that predate the 18th century church along with evidence of the earlier church and of Roman occupation.

The interior today has a magnificent ceiling, originally dating from 1897, but with considerable restoration work in the 1950s. I doubt helium filled balloons were a consideration in the original design of the roof.

A gallery runs along the sides and above the entrance to the church were the organ is also installed:

Inside the church is a lead cistern dating from 1738, The cistern was originally installed in the northwest porch of the church to hold water from the supply from the Thames. It was moved to its current position and the wooden top that now covers the cistern is made from wood recovered from the old front doors that were destroyed by bombing.

Again, whatever the truth of the story behind the clocks, Pearman’s book took me to another church that I have not visited.

After leaving the church, I then walked north along Borough High Street to find my next location:

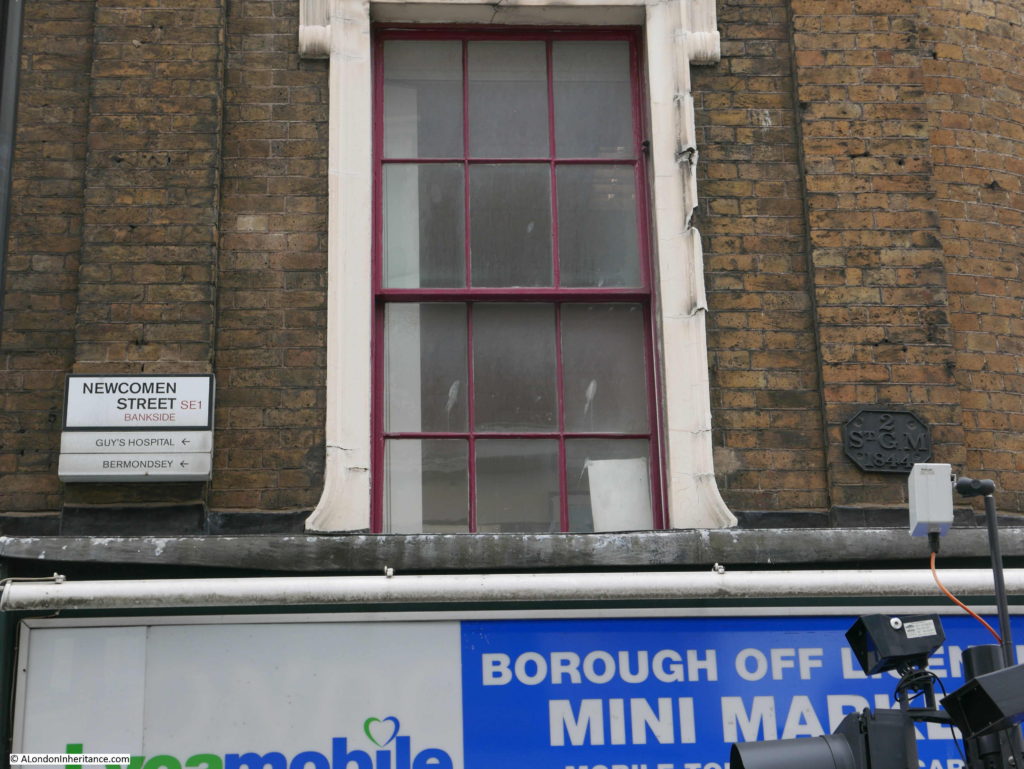

London Bridge and the King’s Arms, Newcomen Street

“London Bridge is falling down, my fair lady – so runs the old song. Well at long last just over a century ago, it did fall down, or rather was pulled down. Very few traces of it are left, but here on the wall of the King’s Arms in Newcomen Street is the coat of arms which once adorned the Southern Gateway of the old bridge.”

To find the King’s Arms pub, I turned off Borough High Street into Newcomen Street to find much of the street closed off for the repaving of the street. It will look really good when finished, but as with the church of St. George I do wonder why so many of the places I visit to photograph seem to be impacted by building works.

It was hard to get some decent photos due to the road works, however the subject of my visit was easy to find. The King’s Arms pub is a short distance down the street and extends slightly into the street resulting in a narrow length of roadway.

In the centre of the building frontage is the rather impressive coat of arms referred to by Hugh Pearman.

The coat of arms are from the gate built at the southern end of the old London Bridge and date from around 1728. The gate was demolished around 1760 and apparently the coat of arms were rescued and mounted on the pub.

The current pub building is clearly not from the mid 18th century, and was built in the late 19th century, hence the reference to King’s Arms 1890 at the top of the coat of arms.

At the bottom is a reference to King Street. The street has undergone a number of name changes over the years.

If you walk Borough High Street, there are a number of short yards off the street. This comes from the time when Borough High Street was the principle road leading south from London Bridge.

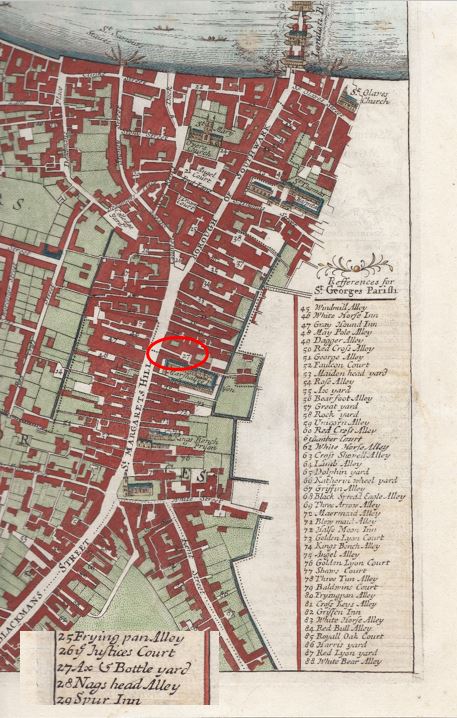

The following map extract is from a map of the Parish of St. Saviours Southwark by Richard Blome (late 17th century but published by John Stow in 1720). Newcomen Street was originally Axe Yard, then Axe and Bottle Yard, which is shown at number 27 in the map (I have ringed the yard and also included the key which includes number 27 at the bottom as the full key is on the left of the full map).

The yard was named after an inn of the same name and the yard was originally the yard of the inn.

The name changed to King Street in 1774. I cannot find confirmation of the reason why, but suspect it was due to the King’s Arms now being in the yard.

The final name change to Newcomen Street happened over 100 years later in 1879. The new name is after Elizabeth Newcomen who died in 1675 and owned property in Axe and Bottle Yard and along Borough High Street. In her will she left the income from the property to her nephew, then to his oldest son, then to the parish of St Saviour’s for the clothing, education and apprenticing of children within the parish.

Almost opposite the King’s Arms I found another interesting building, boarded up, but with some fascinating features and history.

A plaque adjacent to the door records that “John Marshall, founder of Marshall’s charity lived at a mansion house near this spot until his death in 1631 as did his father before him. Marshall’s Charity had its offices here until 1967.”

It never ceases to amaze me how many small charities there are in London dating back centuries and still providing benefits from the original founder’s gift and the Marshall Charity is a perfect example.

John Marshall died childless in 1631. His will appointed trustees to build Christchurch in Southwark and to use funds from his properties for “the Mayntenance and Continuance of the sincere preaching of God’s most holie Word in this Land for ever”.

Almost four hundred years later, the charity is still in operation and based on John Marshall’s original properties from his will was able to give £831,000 in grants in 2016.

The charity supports Christ Church, Southwark, as well as providing grants for the repair and restoration of parsonages and Anglican churches in Kent, Surrey and Lincolnshire. The charity also operates the Marshall’s Educational Foundation which provides financial assistance to students in north Southwark.

Brilliant that such a charity still exists and also a wonderful building which I hope will be sympathetically restored.

In complete contrast, in Newcomen Street I found this hairdressers. I have many themes for photography whilst walking the streets of London and this type of hairdresser is one of these themes – continuing on from the same theme my father started in the 1980s. See the post: Hairdressers of 1980s London.

Another theme is parish boundary markers. I have photographed hundreds of these and here is one on the corner of Newcomen Street – an 1844 marker for St. George the Martyr – the church I had just visited.

My next stop is in Park Street, a street which runs from Borough Market to Southwark Bridge Road, however before arriving at my next destination, at the junction of Park Street and Maiden Lane is this plaque recording the results of archaeology excavations just a little further north where the remains of buildings from the early years of Roman occupation were found including a warehouse.

Further along in Park Street I found my next location at number 4 on the map:

Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, Park Street

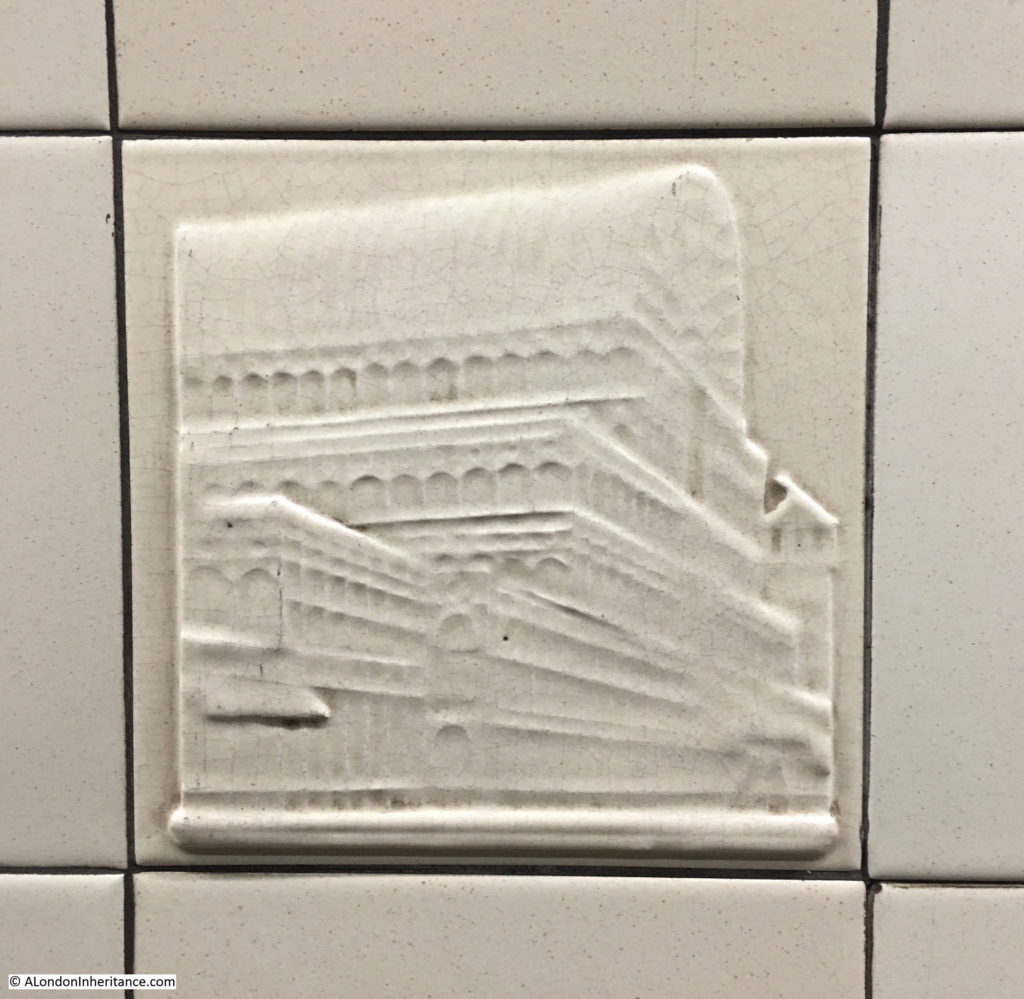

“Running parallel with Bankside is narrow Park Street. here, on the site where this plaque is affixed to a brewery wall, was Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. the Plaque shows the theatre, Old London Bridge and the neighbourhood as it was in those times. Every year at the time of Shakespeare’s birthday draws nigh, players, in costume, re-enact here, in the street, scenes from his plays.”

The brewery, which once ran to the east along Park Street is long gone, however the plaque has survived and is now mounted on a short length of wall in front of a semi-circular fenced area, behind which are a number of information panels which detail the history of the theatre and the excavations which located their remains.

It was in 1989 that the Museum of London carried out excavations on the site and found a small amount of remains of the theatre. Inset into the surface of the courtyard between the two buildings behind the plaque is a set of stones which show part of the circumference of the outer wall of the theatre.

The brewery that Pearman refers to as the original mounting for the plaque was the Anchor Brewery that ran from the current location of the plaque and to the east along Park Street, where we can find a plaque recording the history of the brewers who operated the brewery.

Park Street is still a reasonably narrow street as recorded by Pearman, although I suspect the re-enactment of Shakespeare’s plays near his birthday are not held in the street since the building of reproduction Globe Theatre.

This is where Southwark Bridge Road crosses Park Street.

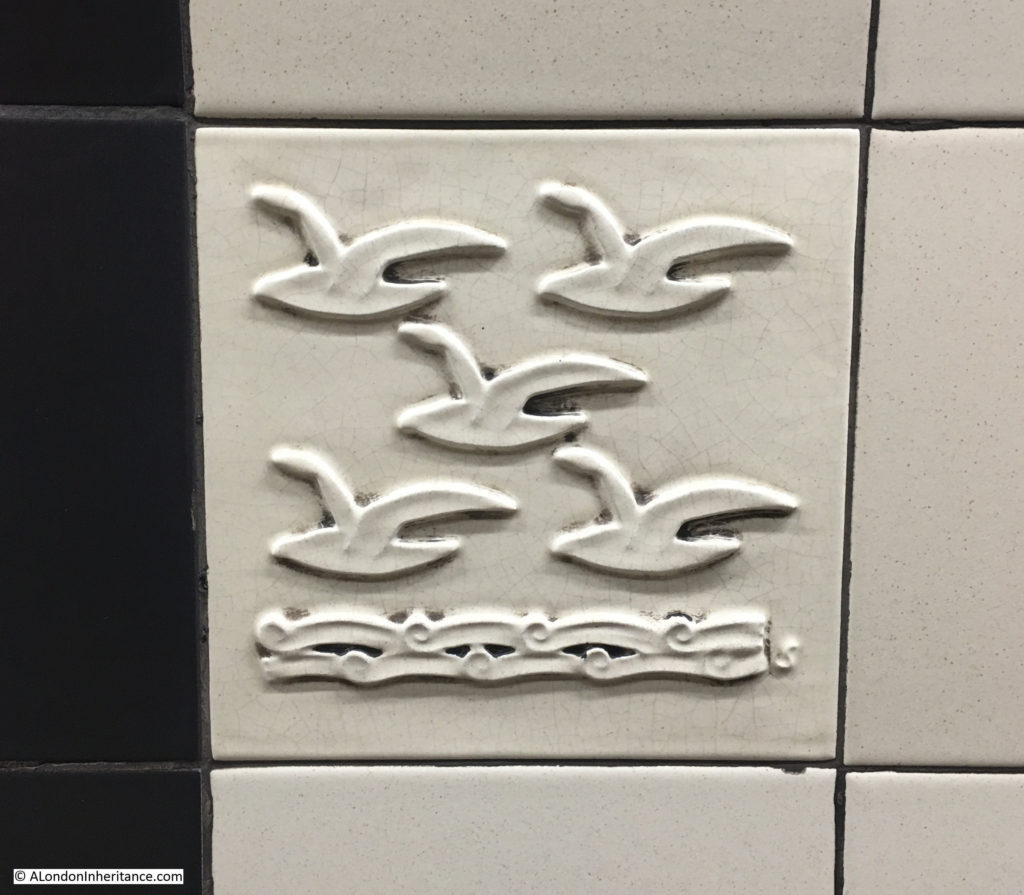

And where the roof of the bridge has a beautiful set of inlaid bricks:

Leaving Park Street, I then walked towards the river, to find location number 5:

Clink Street Bollards

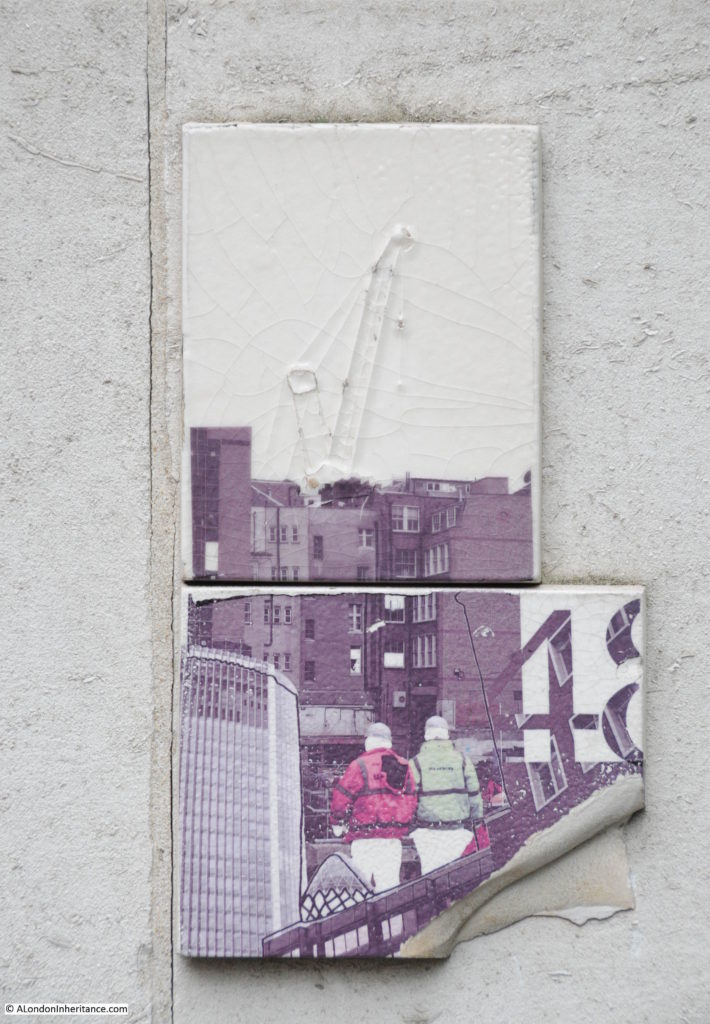

“The origin of the expression ‘clink’ for prison comes from the Clink prison that used to stand where is now the Borough fruit and vegetable market. This post is one of the many, still standing that mark the old boundaries.”

I found a number of these posts where Bank End meets Bankside, in front of the Anchor pub. Whilst they are all painted black unlike the one photographed by Pearman, they are off the same shape and have the same reference to Clink and the date 1812.

One in the corner alongside the bridge:

And a couple in front of the entrance to the Anchor:

Leaving a visit to the Anchor till later, I walked to the next location, number 6:

Cardinal Cap Alley

“Facing St. Paul’s Cathedral, from the South Bank of the Thames, is this little house with the odd sounding name of Cardinal Cap. At the time of the erection of the Cathedral, Sir Christopher Wren is said to have lived here and to have been ferried across, daily, to superintend the building of his masterpiece.”

I wrote an article about Cardinal Cap Alley and the house, 49 Bankside – the article can be found here.

The house was not home to Sir Christopher Wren, however it has a much more interesting history as documented by Gillian Tindall in her excellent book “The House by the Thames” which I covered in the post, including my father’s photo of the house as it was in 1947.

This was the photo of the house and surrounding from my 2015 post.

Whilst some of the stories of Southwark in Curious London cannot be confirmed by evidence, they tell of the stories that have grown up across the city to add interest and a sense of history to the streets.

They also provided me with a new route to walk, and the discovery of a couple of places in London that I had not seen before. Trinity Square is fascinating and whilst I have walked past the church of St. George many times before, I have never had the incentive to look inside.

There are many more stories to tell of this small area of Southwark including the King’s Bench, White Lion and Marshalsea Prisons. A wall of the latter Marshalsea can still be seen near the church of St. George.

It is also still possible to make out the alleys and yards that once led off from Borough High Street – a legacy from the time when many of these would have been occupied by Inns, serving travelers before they reached the bridge leading into the City of London.

Curious Southwark is a fascinating place to explore.