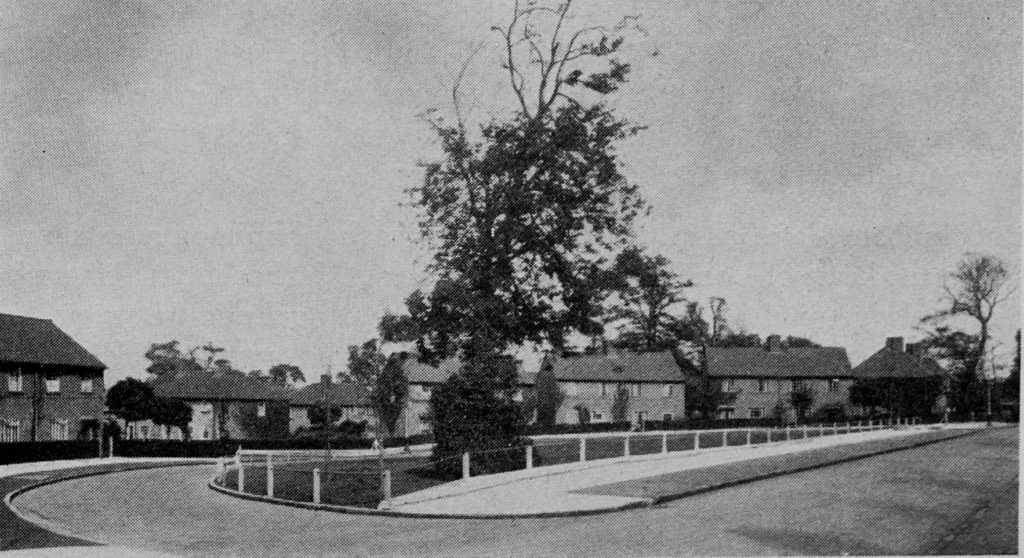

The primary aim of the blog is to track down all the locations of the photos that my father took of London. With a number of the photos he had identified the location, either written on the photo if printed, or later labeling some of the negatives. Many had no identification so I have been tracking these down based on the scene in the photo.

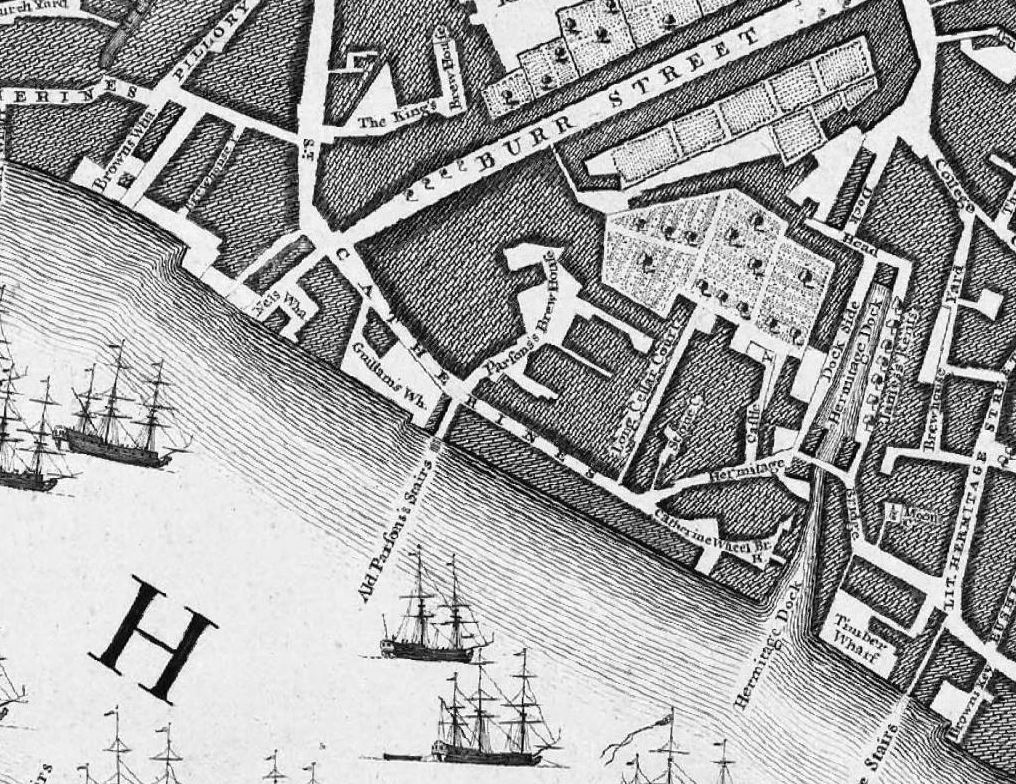

I thought the subject of last week’s post was easy as it had been labelled Thomas More Street, however despite walking up and down the street a couple of times, I could not identify the location. The street had the high brick walls, but I could not find the curve on the street.

Fortunately, the expertise of readers came to help with the identification of the correct location. It was not Thomas More Street, but nearby in St Katharine’s Way, so before turning to the subject of this week’s post, I need to provide an update on last week’s post (I will be re-writing the post, but wanted to get this update out).

This is the photo from last week’s post:

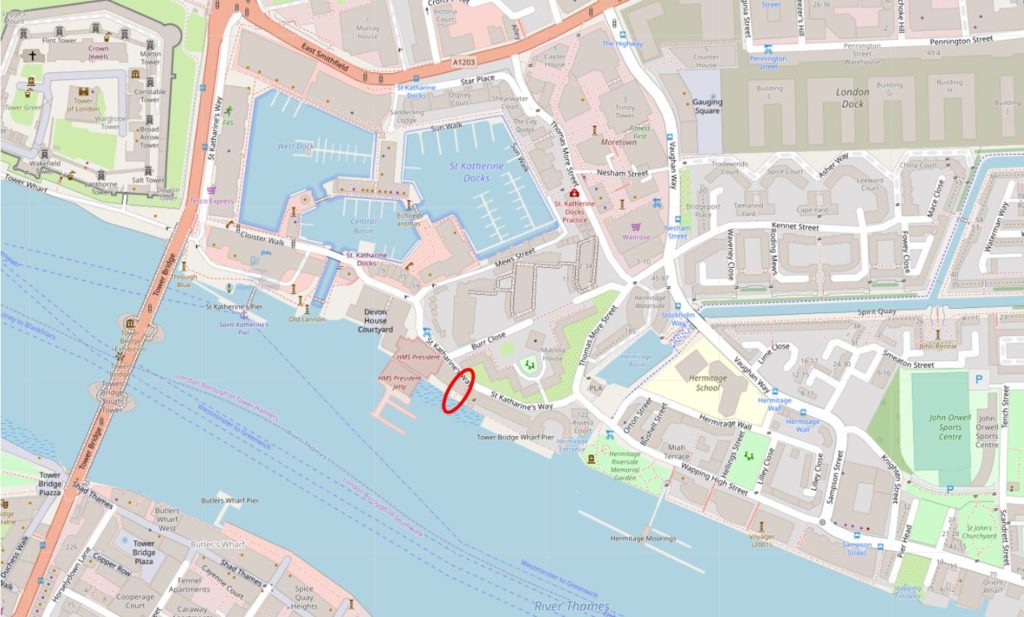

Andy Murphy commented on the post to identify the correct location and also provided a link to the following photo from the Britain from Above website:

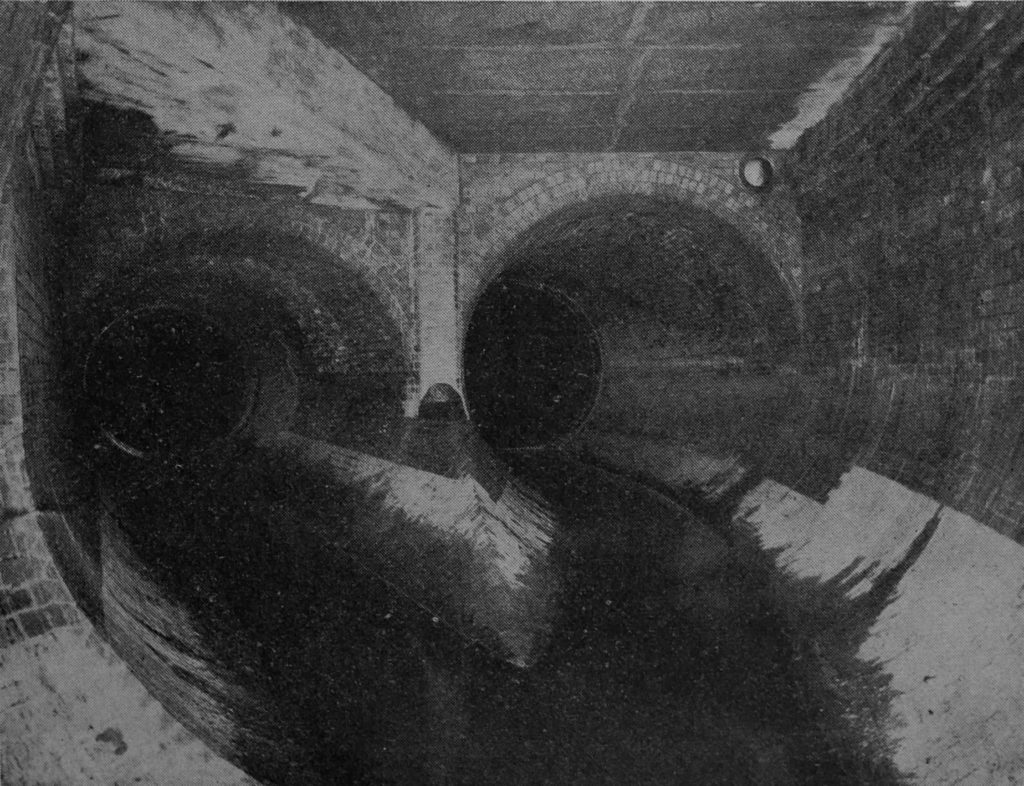

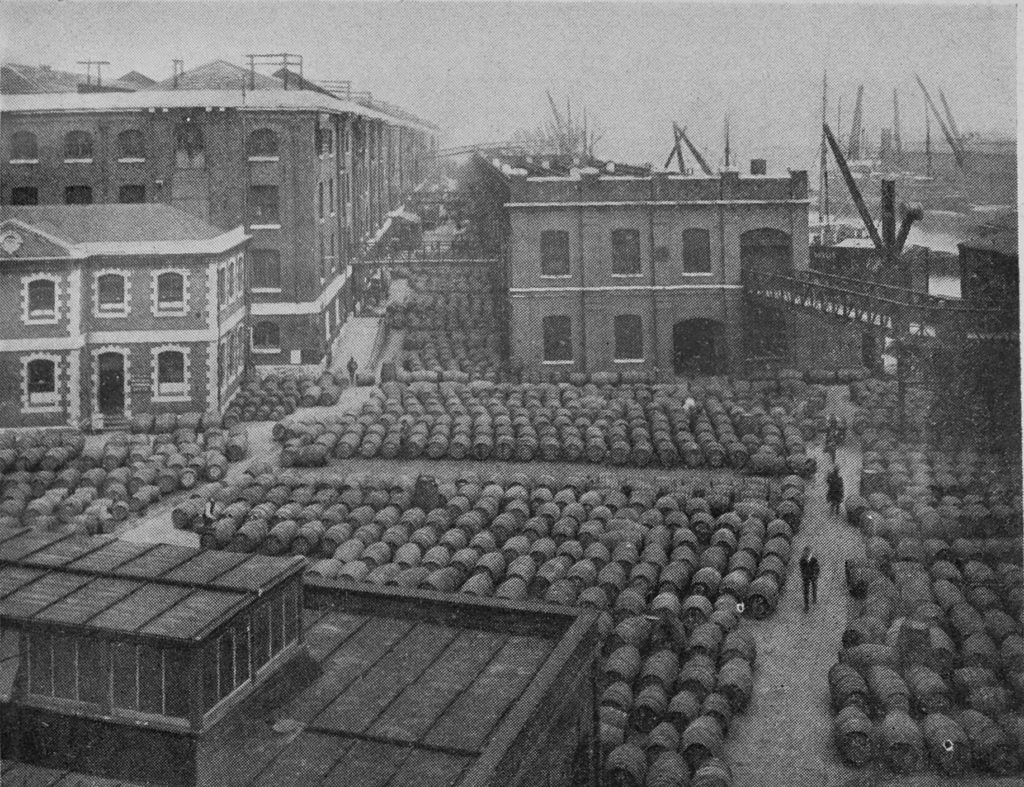

The twin docks that are St Katharine Docks can be seen in the lower right of the photo. There is a single entrance to the dock from the River Thames, and a bridge can see seen over the dock entrance.

This is a swing bridge, and it was just to the east of the swing bridge that my father was standing when he took the photo looking east.

I have enlarged the specific part of the above photo to show the area in my father’s photo:

In the above photo it is just possible to see the wall along the northern edge of the street, the curve of the street which would be seen when standing in the straight entrance to the swing bridge, and the main building, the large warehouse in my father’s photo can be seen along the northern edge of the street.

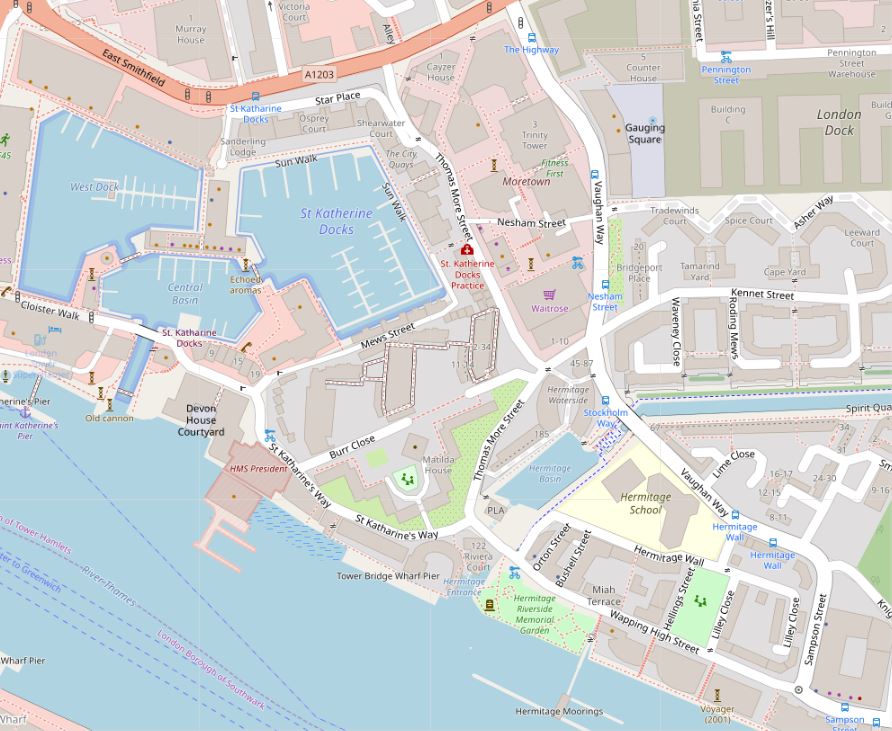

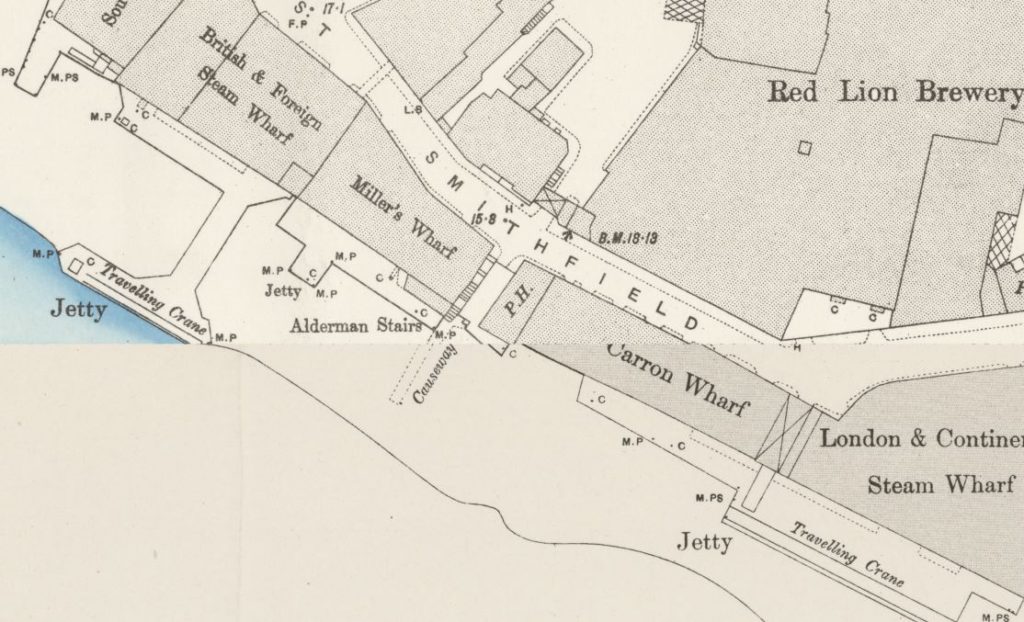

Malcolm used the OS maps to identify the location, and the following map extract shows the location:

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

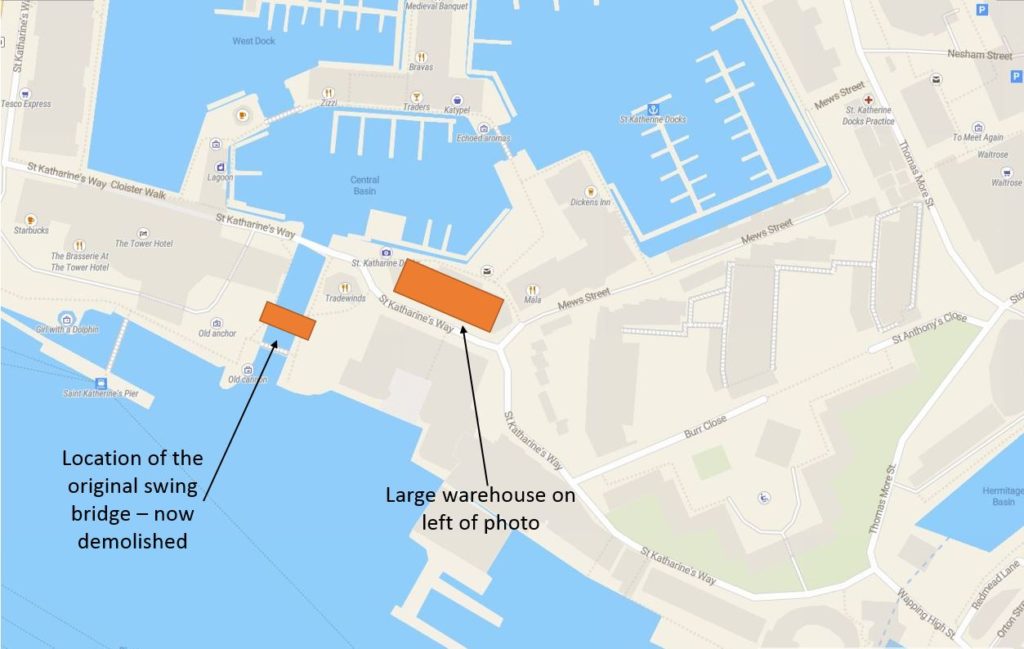

The area today is very different and the swing bridge has disappeared. In the following map showing the same area as it is today, I have marked the location of the swing bridge and the large warehouse (© OpenStreetMap contributors).

Annie mentioned in a comment that she thought she could see one of the features in my father’s photo in photos of the site today.

I wanted to take another look, but work was too busy in the week, leaving yesterday, the hottest day of the year so far, as an opportunity to investigate further.

This is the main entrance to the St Katharine Dock from the River Thames today.

The footbridge and swing bridge in the photo are part of the redevelopment of St Katharine Dock, if you look back at the maps earlier in the post, you can see that the original swing bridge was a short distance along from the footbridge, further in towards the docks.

Comparing the two maps and using the overlay feature on the National Library of Scotland site, the swing bridge crossed the dock entrance, then the road curved to the left, behind what is now the Marina office. This is the view looking across the dock entrance today from roughly where the swing bridge would have been on the western side.

In the above photo, the marina office is the building on the left. To the immediate right of the marina office is a set of steps and a high brick wall.

Crossing over, I took a look at the steps and the wall.

The wall on the right is modern, but the wall on the left looks to be one of the original dock walls. There are bricked up features in the wall and the brickwork is rough and aged. Very similar to the dock walls in Thomas More Street.

This is the view along the footpath alongside the wall.

For some reason, the footpath is raised, with steps at both ends of the footpath, so the walls would originally have been much higher. No idea why the footpath has been raised.

At the end of the footpath, this is the view looking along St Katharine’s Way. The large building on the left is occupying the space where the large warehouse was in my father’s photo (see the maps for details).

My suspicion was that the wall that runs along the footpath, to the rear of the marina office, could be the wall in my father’s photo on the left of the street, towards the warehouse.

I was checking the wall for features, probably to the amusement of those also walking along the footpath.

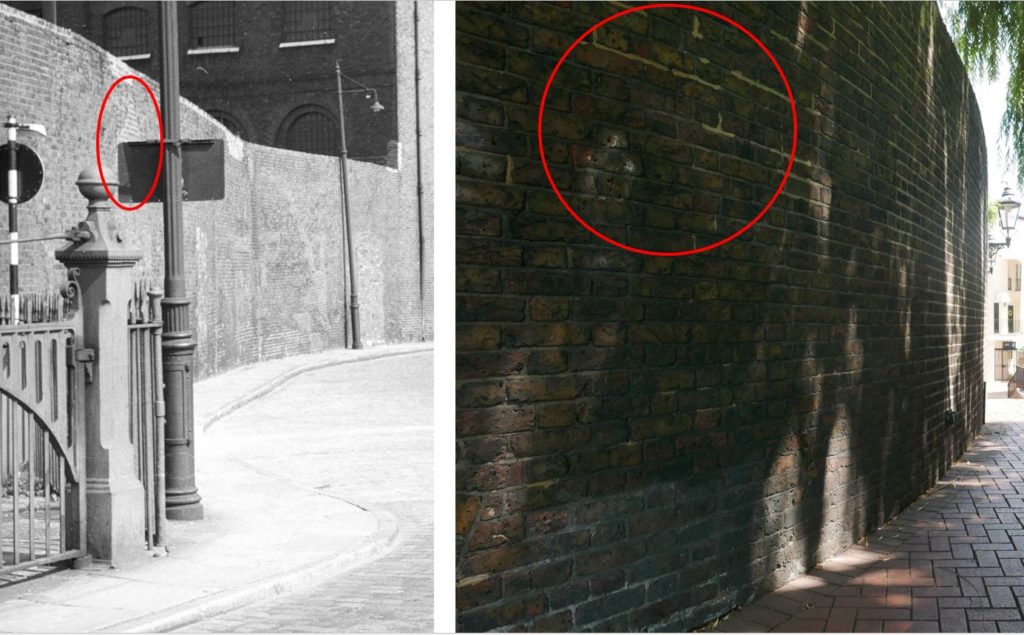

This may be me seeing things that are not there – wanting to find evidence where there is none. I will leave it to you to judge.

On the wall on the left of my father’s photo is a triangular feature. The wall today is in shade, rather than the bright sunshine of my father’s photo, but there also appears to be a triangular outline in the brick wall today, in roughly the right place along the wall.

I have taken extracts from photos earlier in the post and marked this feature – not easy to see in the 2019 photo.

This area has changed very dramatically in the 70 years since my father took the original photo, and it may be that I am seeing things which are not there, wanting to find something remaining today from the 1949 photo, but it does look right.

I have no idea why my father wrongly labelled the street. This is only the second example I have found in five years of the blog. The other photo that was wrongly labelled was Bevington Street in Bermondsey. I suspect the reason why these photos were wrongly labeled is that he would develop the film some weeks after taking the photos and finishing a role of film, and this gap after walking multiple London streets resulted in an error, or forgetting exactly the location of the developed photo.

The other question from last week’s post was the uniform of the man walking along the street. It is now clear that he was walking towards St Katharine Dock, so perhaps he was walking towards the start of work. There were a number of suggestions as to the uniform and cap badge, but the lack of detail in the photo could not help with a firm identification.

Thanks to everyone who commented on last week’s post – your feedback helps make writing these posts so enjoyable. So now to the subject of this week’s post.

Barge and Ship Fires on the Thames

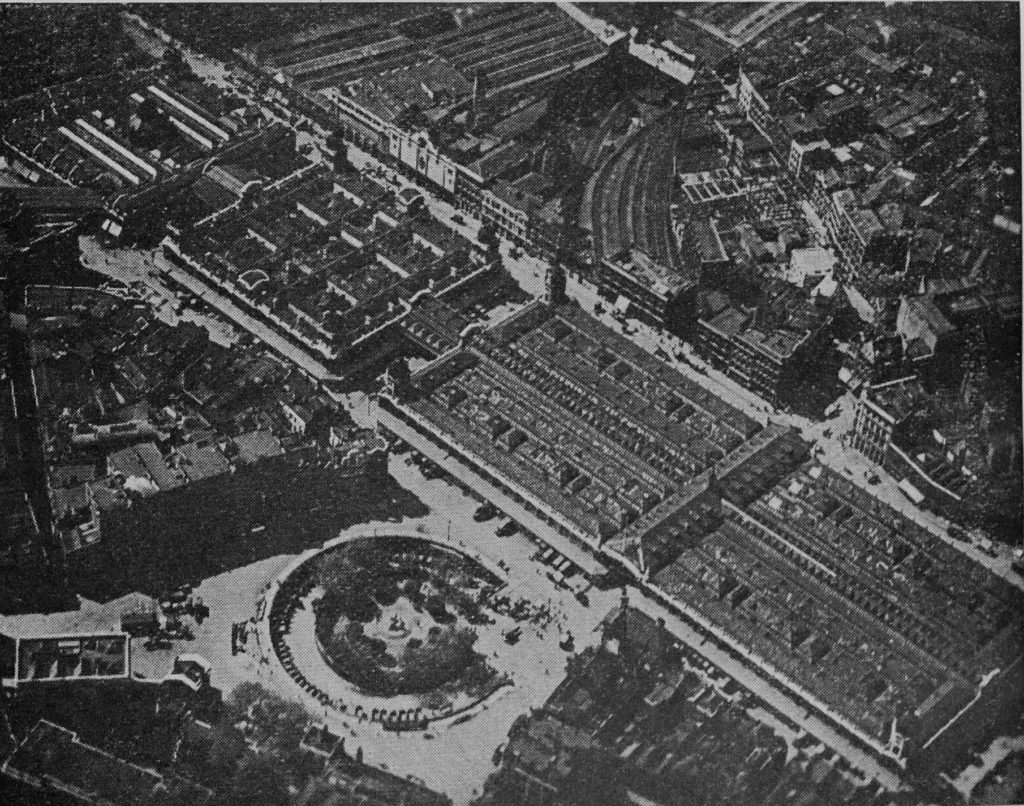

My father took the following photo from Bankside looking across to the north bank of the Thames, with St Paul’s Cathedral in the background.

To the right, there is a fire on a ship with black smoke partly obscuring the scene.

The same scene today:

The scene is both much the same, and very different.

St Paul’s Cathedral is still the dominating feature, and it is good to see that the height of buildings between the cathedral and the river are much the same, so the view of the cathedral is very similar.

On the river front, the only building that is the same in both photos is the warehouse on the right.

The Millennium Bridge on the left is the main new feature at river level.

Looking at the photo, I wonder if the reason my father took the photo was perhaps the fire.

Shipping on the River Thames carried a considerable variety of goods and materials, many of which were highly inflammable. This, along with a lack of regulations around safety and fire prevention, how goods should be carried, the fire needed to raise steam in steamships and the sheer volume of traffic on the river probably resulted in many such examples.

To investigate further, I had a look through newspaper reports to understand how frequent these were, and the types of goods that were at risk.

31st March 1845 – A Ship On Fire In The Thames

Yesterday afternoon information was received at several engine stations that a fire was burning on board the brig Betsy, Captain J. Rich of Penryn, lying off King Edward Stairs, opposite Rotherhithe. For sometime the greatest fears were entertained that the whole vessel would fall sacrifice to the fury of the flames, which were then burning brightly and fiercely in the after cabin. The floating engine, manned by one hundred men, was got to work, and a vast body of water poured into the cabin. At length the flames were subdued, and all danger of their further extension at an end, but not before the after cabin and its contents were nearly consumed. The fire from the cabin stove, from some cause which is unexplained, is said to have caused the disaster. The vessel, which is the property of Capt. Tranery, of Penryn, is said not to be insured.

23rd March 1877 A Barge Fire On The Thames

A barge laden with straw, caught fire on the Thames, near Blackfriars, on Monday. The barge was speedily got away from a number of others, and removed to mid-stream, where the fire floats played upon her until the fire was extinguished.

12th September 1871 Petroleum Barge on Fire In The Thames

The barge City of Rochester, belonging to Mr Burkett, of Greenwich, laden with petroleum, while lying in the upper part of Halfway Reach, London, on Saturday morning, took fire, and was burned to the water’s edge. the barge had received the petroleum from two vessels, the Harmony and Ennis, discharging at the petroleum buoys, near Erith.

15th February 1899 (a single paragraph in among other news items)

A barge took fire in the Thames this morning, and of her crew of three men, one was burned to a cinder, and the others were so severely injured that they are not likely to recover.

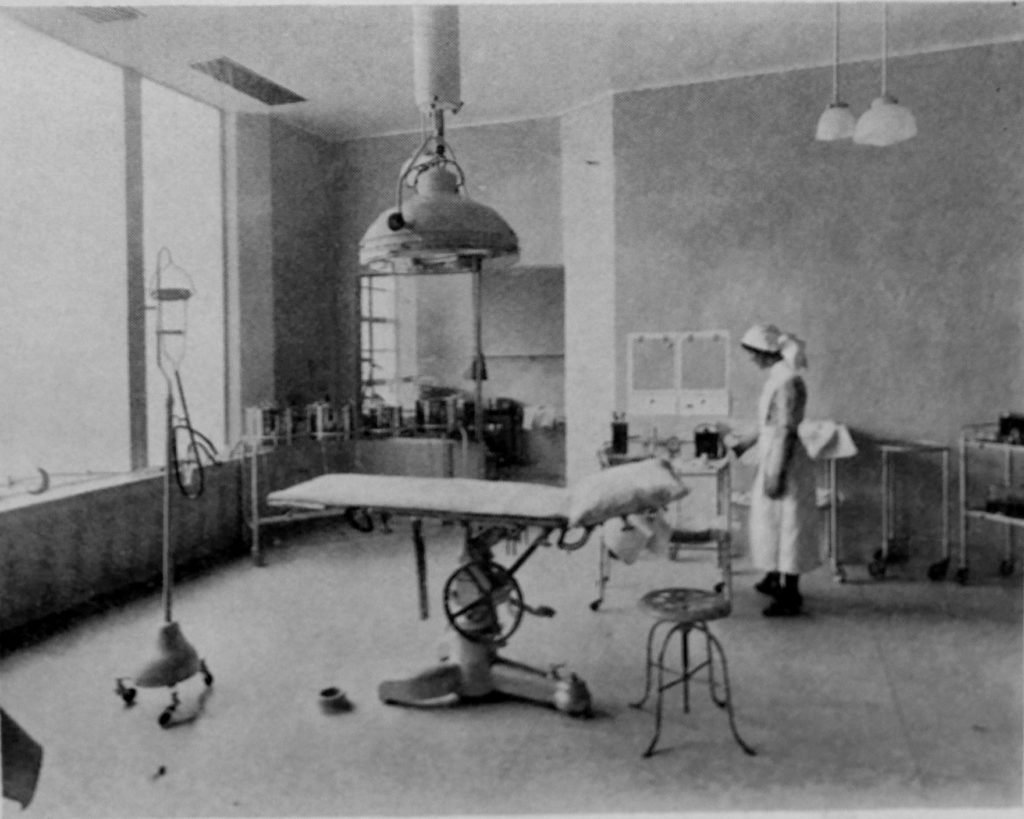

3rd January 1902 – A Smallpox Ship On Fire In The Thames

A fire broke out last evening on board the Endymion, a smallpox hospital ship, in the Thames, near Dartford. The vessel is one of three ships moored together, and used for acute cases. The Metropolitan Fore Brigade were apprised by telephone, and immediately sent down the Alpha fire float, which was moored at Blackfriars Bridge. The fire brigade authorities were later informed that the outbreak occurred in the stokehold of the Endymion.

The fire was overcome this morning, having smouldered all night in the stokehold, At the time of the outbreak, a number of nurses and attendants were on board, but no smallpox patients. There was no panic, neither was any personal injury sustained.

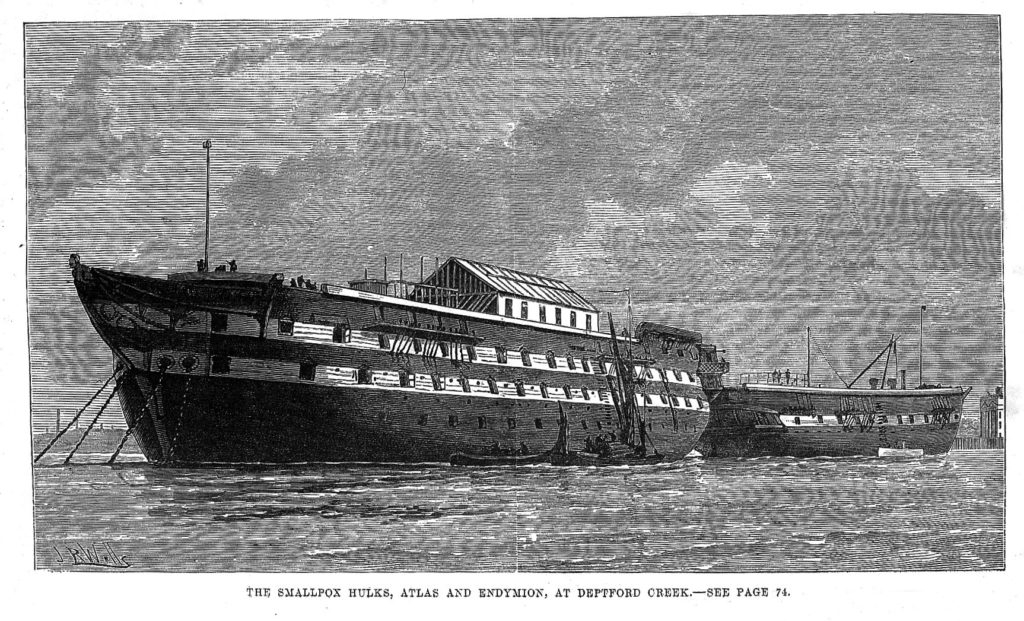

I had no idea that there were smallpox hospital ships on the River Thames. I found the following drawing of these ships (or rather hulks as in the drawing) in the Wellcome Collection.

The ships were the Atlas and Endymion (the subject of the above news report) at Deptford Creek.

Ships used as smallpox isolation hospitals. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

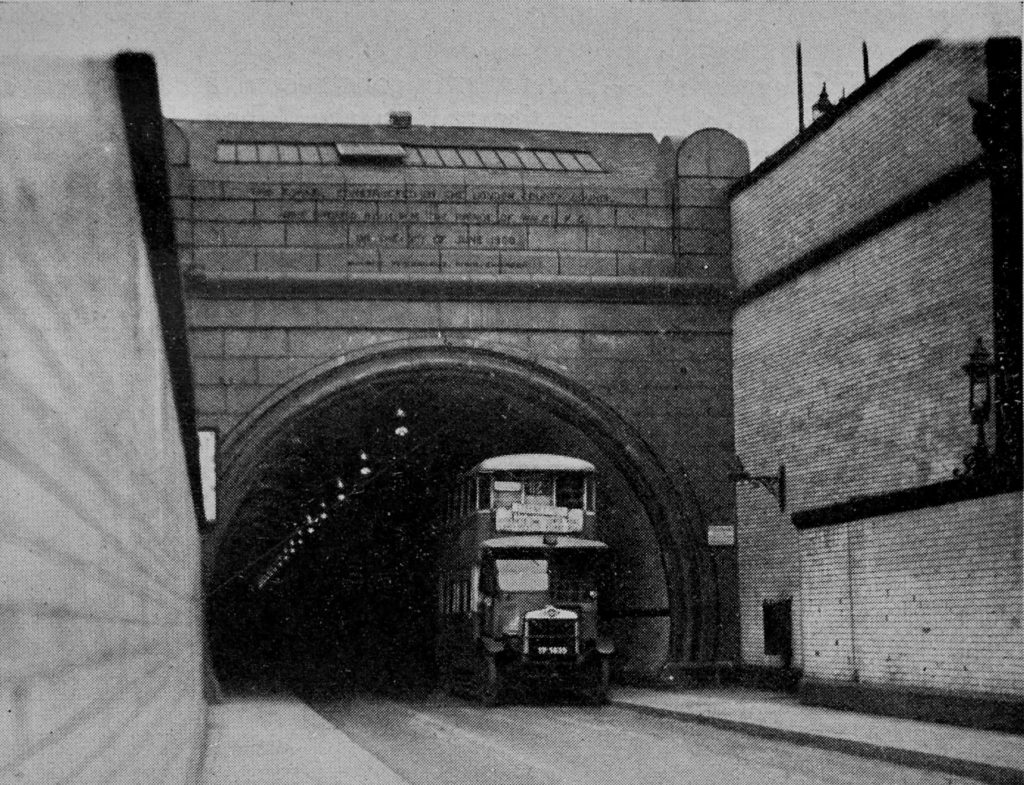

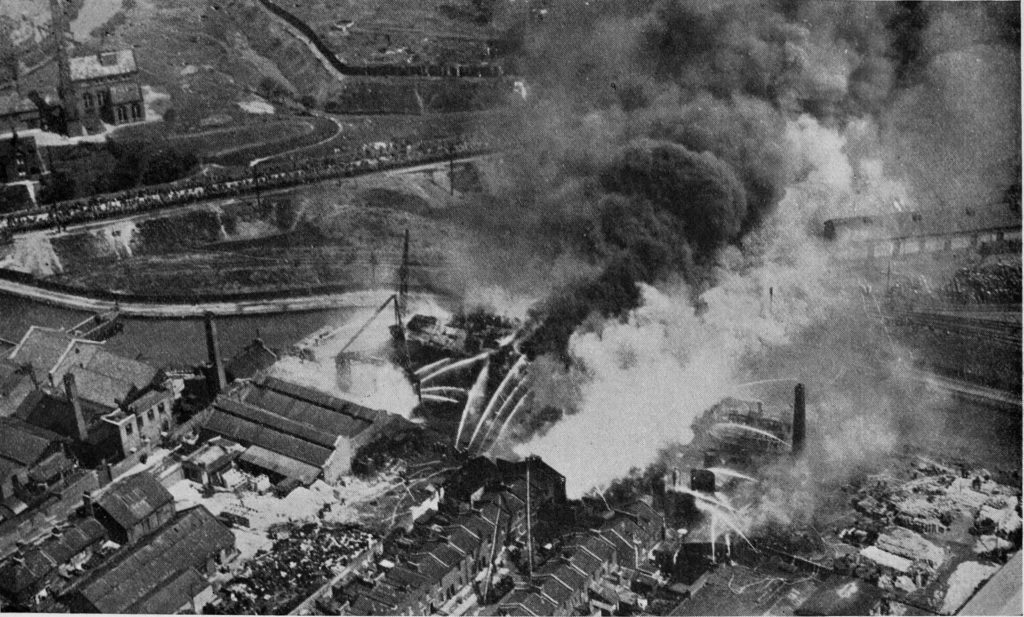

17th September 1906 – Blaze Near London Bridge

Early on Saturday morning a vessel, the Balgownie, belonging to the General Steam navigation Company, was found to be on fire at her berth in the Thames. Carrying a general cargo, the ship came up the Thames on Friday night’s tide, and was berthed near London Bridge, it being intended to unload her on Saturday morning. When the alarm was raised two L.C.C fire floats, Alpha and Beta, were summoned and were quickly on the scene. A number of fire-engines from stations near by were also called.

The vessel was lying just off Hay’s wharf, near Tooley-street. A number of other vessels were near by, and there was some danger that the fire would spread to these ships. The brigade quickly got to work under the command of Captain Hamilton, and a very strong force of water was pumped into the burning vessel’s hold. The smoke and flames had in the meantime created considerable excitement amongst early morning frequenters of the river and bridge, and large crowds watched the operations of the firemen.

After two or three hours work the fire was subdued, although the firemen had been working under considerable difficulty through not being able for a time to get at the seat of the outbreak. After the flames had been put out the fire-boats and the engines from the shore remained in attendance, the floats directing their attention to pumping out water from the hold.

14th September 1910 – Barge Fire On The Thames

The East-end firemen were called last night to a vessel alight on the Thames, and found that the Dutch barge Alberdina, of 200 tons burden, was on fire alongside Foster’s Wharf, in Stanley-road, North Woolwich. The fire had broken out in the main hold, and was just attacking the deck when appliances were set to work and the fire overcome.

24th March 1911 – Ship On Fire In The Thames

The steamer “North Point” was bound for Philadelphia, and discovered on fire shortly after leaving the dock. The crew, which numbered forty, were aroused by the captain, and all saved by tugs. Five sailors, unable to join their comrades, owing to the heat of the decks, lowered themselves by ropes over the side of the vessel, and were then rescued. The vessel in a short time was a floating furnace, the iron plates on her sides being red-hot to the water’s edge. Eventually the “North Point” was beached.

24th April 1912 – Ship On Fire In The Thames

London bridge was crowded by sightseers on Saturday evening owing to the fact that a fire had broken out on the steamship Prince Albert, lying off Nicholson’s Wharf, Lower Thames-street. The alarm was given at half-past five, and the brigade authorities ordered out ten motor pumps and steamers and two powerful river floats. The vessel, of 3,000 tons burthen, is owned by the Ocean Belgian Steam Navigation Company of Antwerp, and had recently arrived from Italy with a general cargo, which included sulphur, hemp, and green fruit. Owing to the fumes of the sulphur, a number of smoke helmets had to be used by the firemen, who were engaged for several hours before the outbreak was suppressed, this being accomplished by the flooding of No. 2 hold. The work was very difficult, as the firemen could not remain for any length of time at close quarters, and they were relieved at short intervals by fresh relays. Beyond the damage to the one hold, the vessel received comparatively slight injury.

16th December 1919 – Explosives On Board, Three Barges On Fire In Thames Dock

A serious fire broke out this morning in three barges laden with explosives lying in the Thames off Dagenham Docks. Explosions followed, which prevented the local fire engines coming close to the barges. Fire floats and fire engines subsequently got to work, but up to noon had made no impression and there were further minor explosions.

Efforts were made to sink the barges before they blew up, and the fireman worked under dangerous conditions to themselves. It was not believed that the property on shore would be in much danger if the barges ultimately blew up. So far there have been no casualties.

16th November 1921 – Ship Fire On The Thames, Unusual Spectacle For City Workers

Thousands of people on their way to the City this morning witnessed a fire on board a large steamer lying in the Thames near London Bridge on the north side of the river, at Fresh Wharf.

The vessel, the S.S. Kingestroom, of 796 tons gross register, carried a general cargo, including rum and paper. River floats pumped large volumes of water into the affected parts of the ship, and within about three-quarters of an hour the outbreak was mastered.

The main seat of the fire was among some rum barrels. These blazed fiercely, giving off a pungent odour. Then some full barrels became involved, and, these bursting, the contents ran over the decks. At midday hundreds of gallons of rum and water were being pumped from the ship.

19th September 1925 – Its Own Extinguisher

A barge caught fire in the Thames, and though fire floats were soon on the spot, the outbreak was extinguished by the barge sinking.

The above is just a very small sample of news reports of fires on board barges and ships on the River Thames – all the way from central London, out along the river to the estuary.

The river was a dangerous place.

It is perhaps surprising from a 21st century viewpoint that a ship carrying a mix of sulphur, hemp, and green fruit would berth in the heart of the City. The impact of burning sulphur must have been terrible, however this was normal for the time, when the same ship would carry a wide range of goods and materials and there were very few restrictions on where such ships could berth.

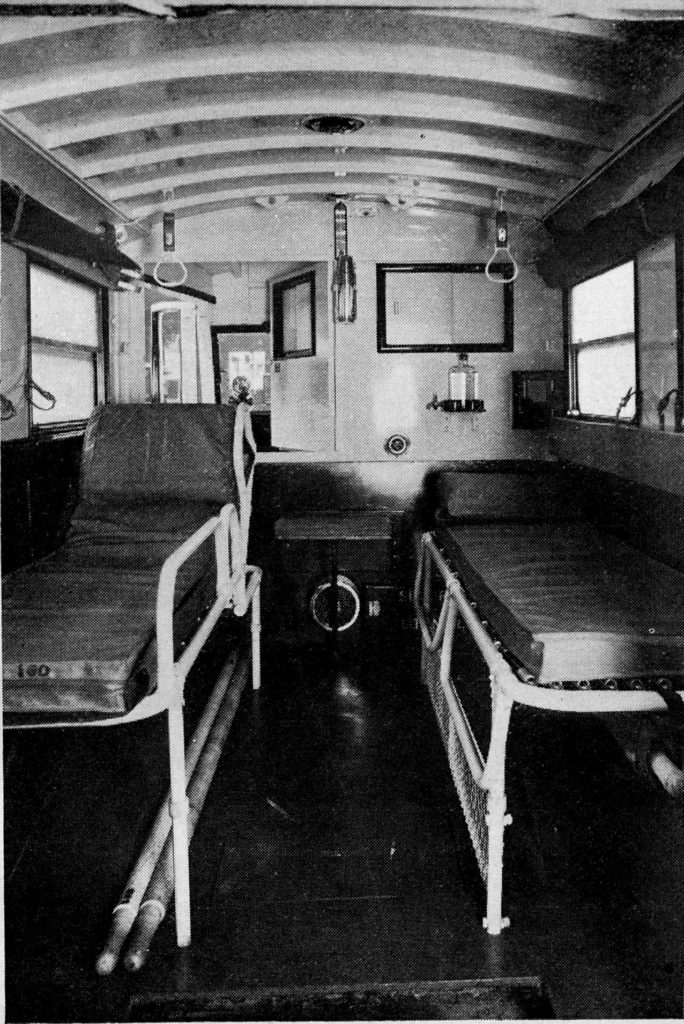

Fire boats or fire floats were a key weapon in the fire brigades arsenal of tools to fight fires on the river, and also fire onshore, from the river.

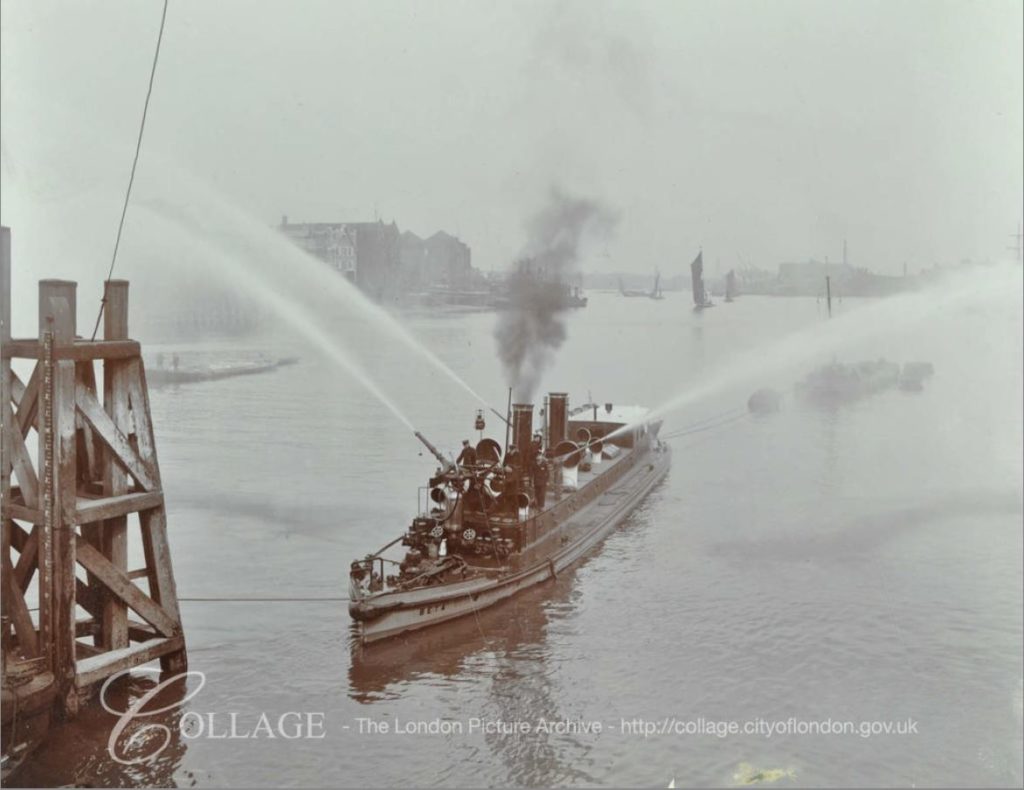

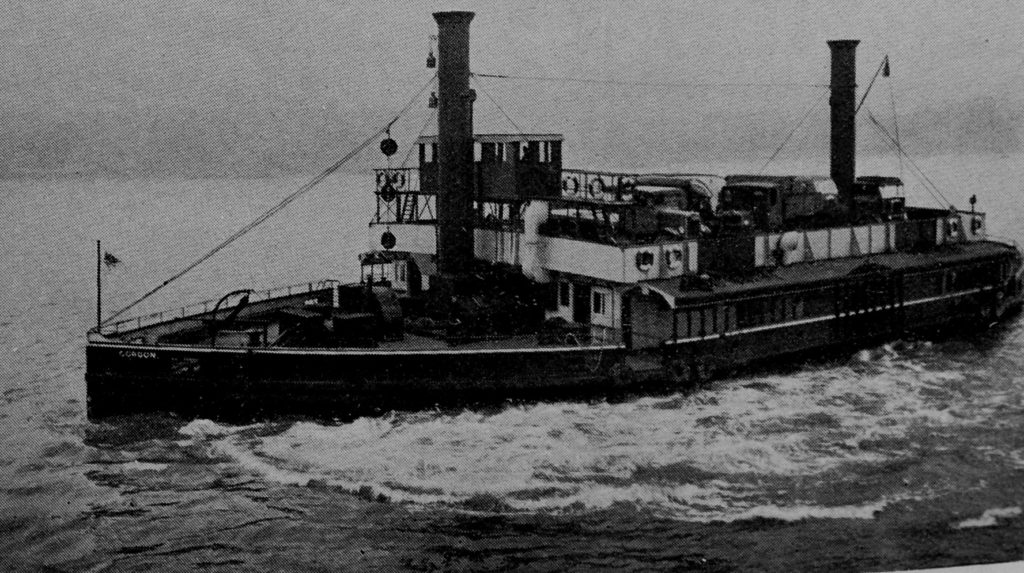

The following photo from 1910 is of the fire float ‘Beta III’.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0487_2358C

These boats were equipped with powerful pumps drawing water directly from the river and able to direct powerful jets of water towards a fire.

A couple of years ago I was on board the fire boat Massey Shaw and saw an early fire boat in action. I wrote about the day (with video) in this blog post. The following is a view of the Massey Shaw pumping water.

The London Fire Brigade still has two fire boats available, and these new boats are far more sophisticated than earlier boats. They are able to change the way in which water is pumped towards a fire, from a powerful directed jet of water, to a dense mist of water.

When I was on the Massey Shaw, we were joined by one of the current fire boats, the Fire Dart.

Both pumping water was an impressive sight, and it was possible to imagine how ship fires would have been fought on the river, when it was full of goods traffic,

Sorry, that was a bit of a long read.

The feedback to last week’s post was so informative that I had to revisit and investigate further and I wanted to write a new post.

Just shows how much there is to discover about this fascinating city.