Before today’s post, I have just added a couple of new dates for my walks. Dates and links for booking are as follows:

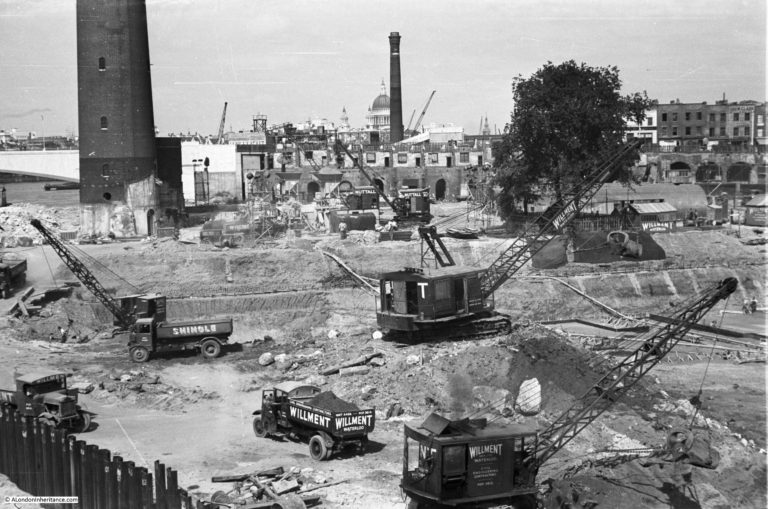

The Southbank – Marsh, Industry, Culture and the Festival of Britain is on Saturday the 20th of July– Sold Out- The Lost Landscape and Transformation of Puddle Dock and Thames Street is on Sunday the 18th of August – Tickets Available

The Lost Streets of the Barbican is on Sunday the 25th of August– Sold Out

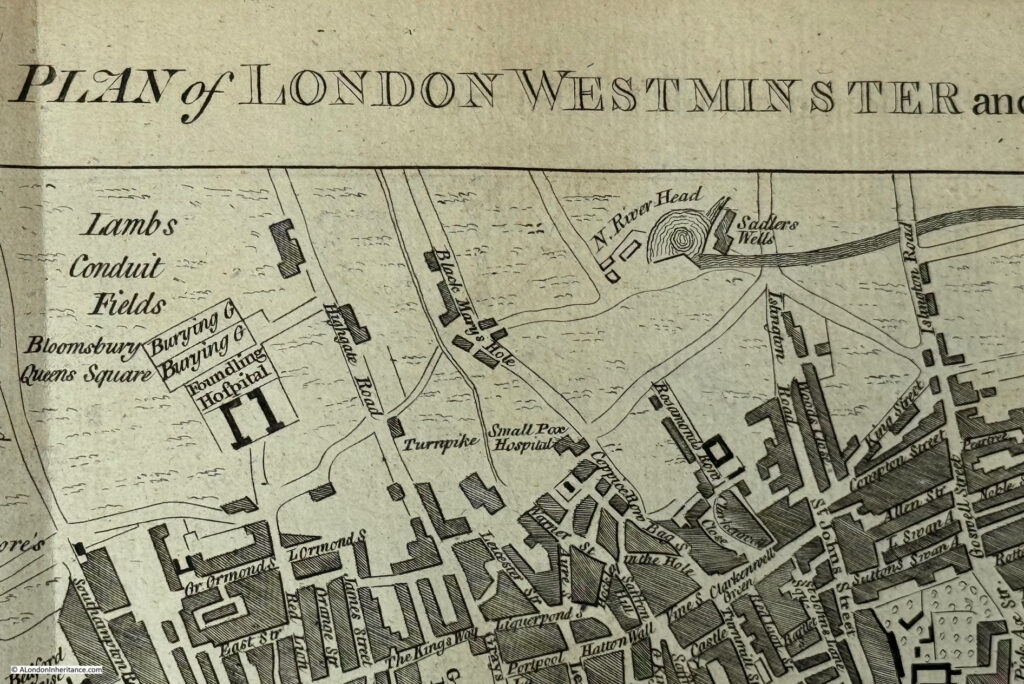

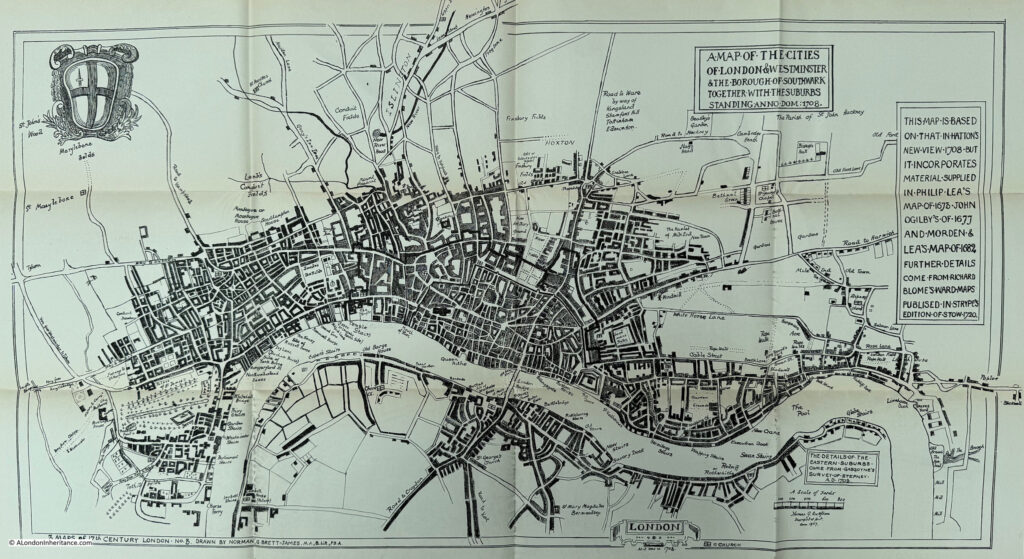

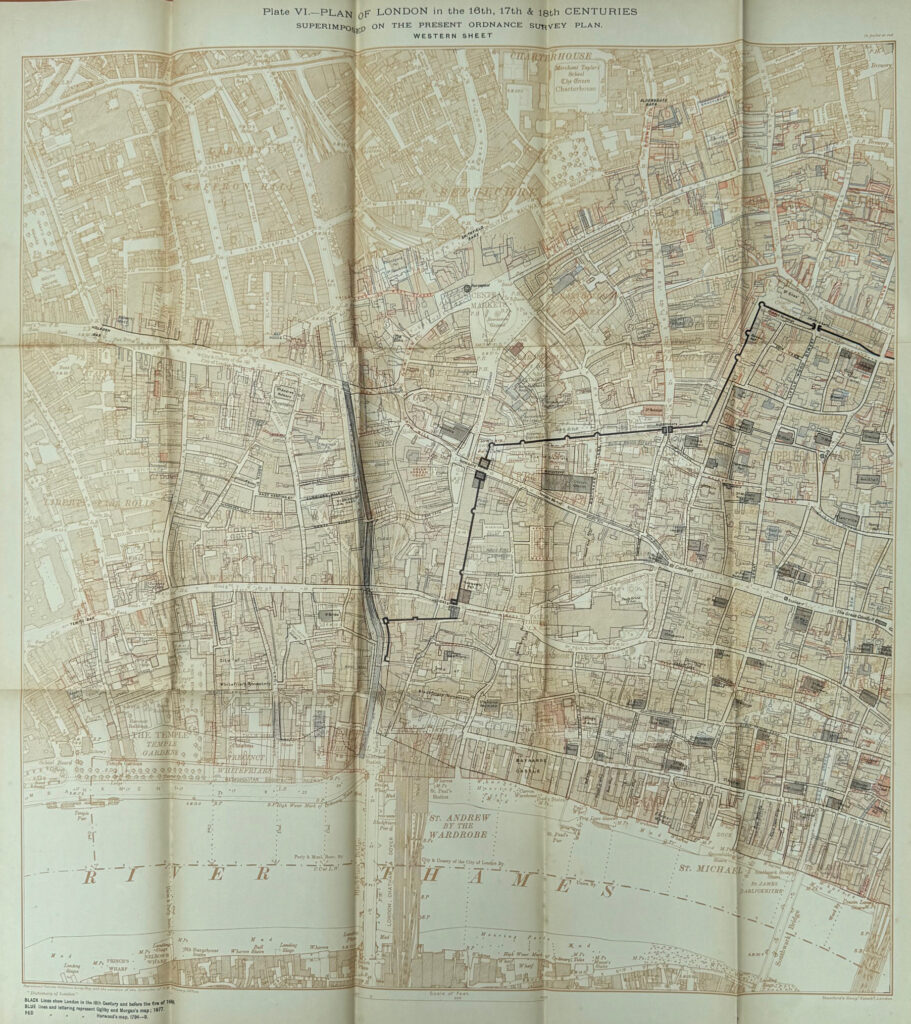

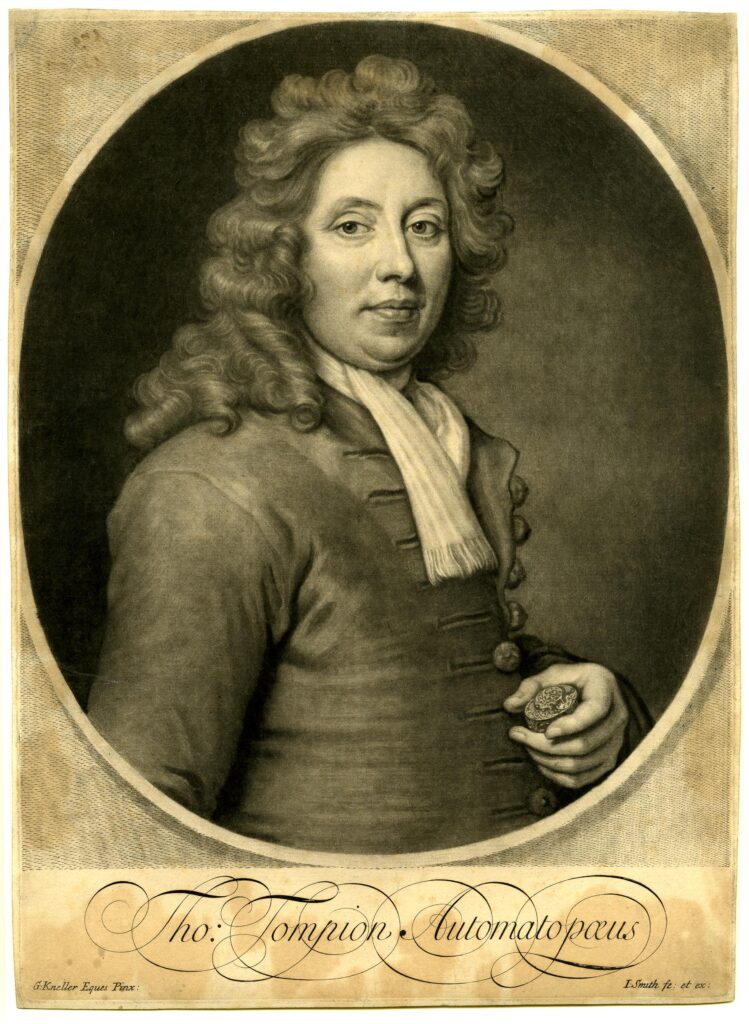

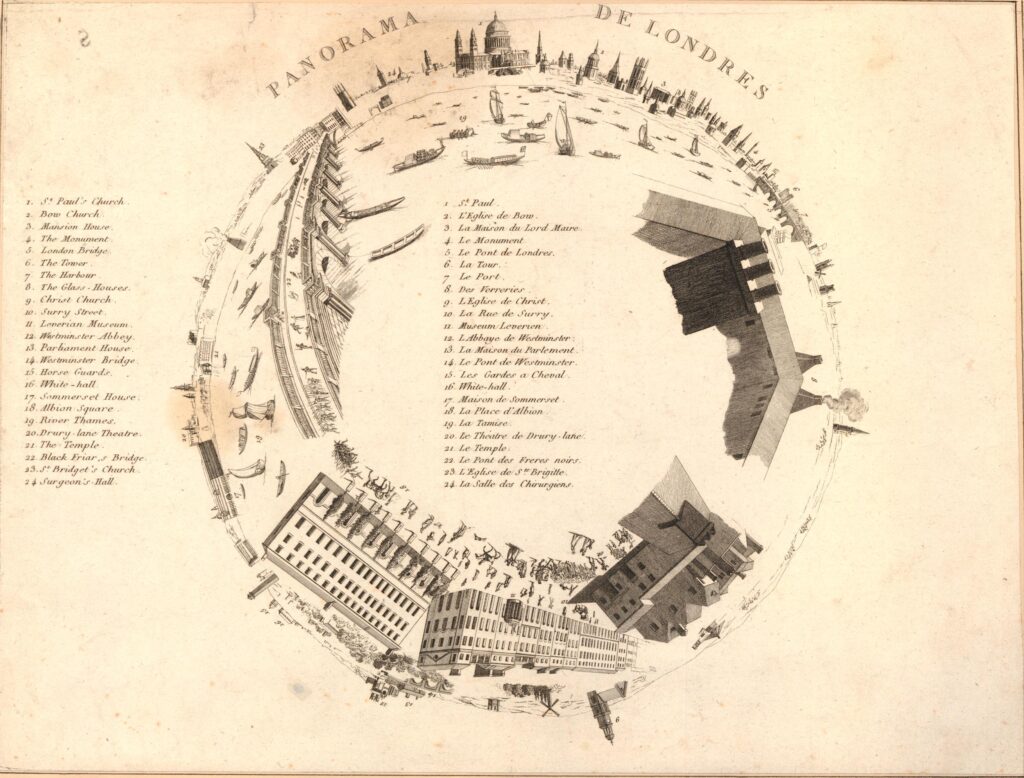

A few week’s ago, my post was about London Maps, and I included one of the strip maps by John Ogilby, who had the impressive title of His Majesties Cosmographer.

John Ogilby was a fascinating character. Born in 1600 in Scotland, he had many professions including a dancer, teacher, translator, publisher and map maker.

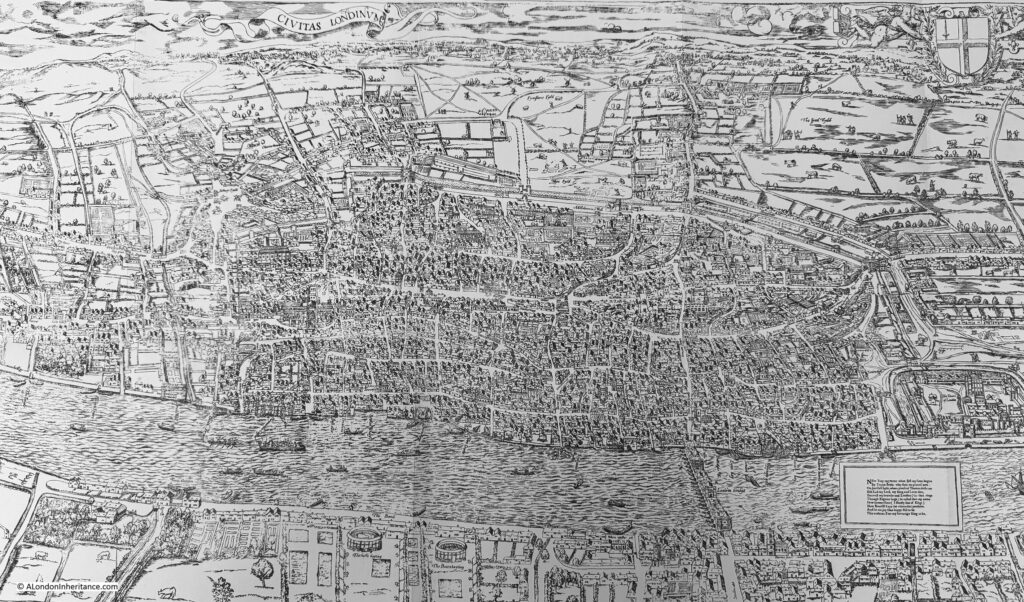

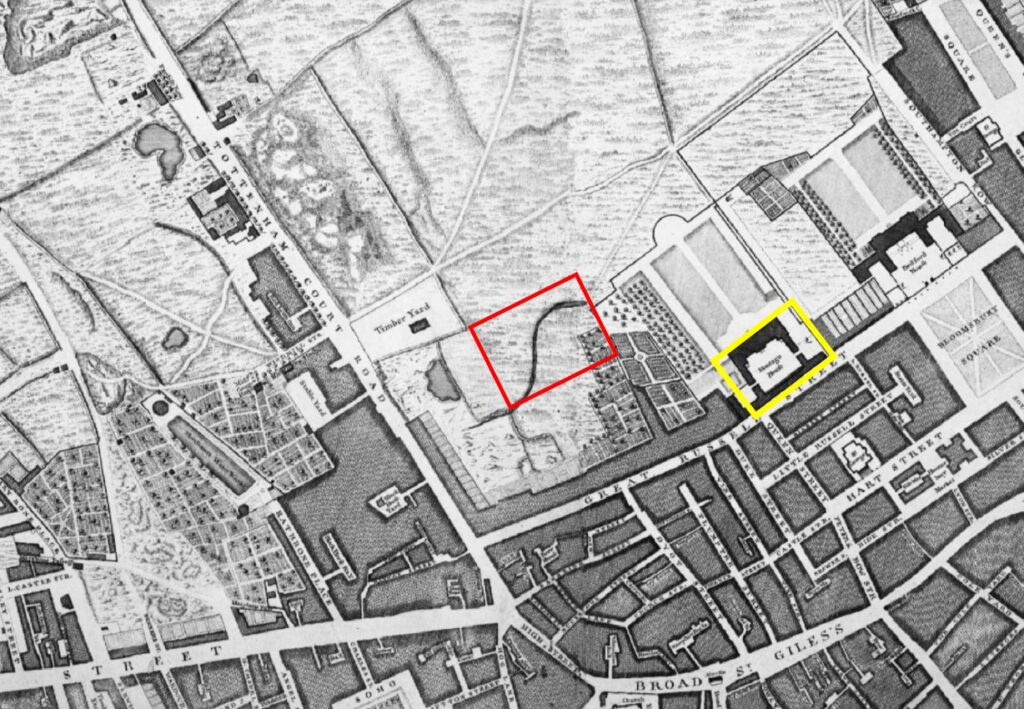

With William Morgan, John Ogilby created a very detailed map of London which was published 10 years after the Great Fire of London in 1666 (although it was probably surveyed before the fire). You can find the map on the Layers of London website, here.

Ogilby is probably best known for his atlas of all the major routes in the country, which he published in 1675 under the name of Britannia.

Routes were shown in a strip map format, where several strips were used to follow a route from source to destination. Along the route, towns and villages were listed, as were geographic features, roads leading off the main route, with their destinations listed, landmarks along the route, distances etc.

The map featured in the previous post was from London to Portsmouth, a route which started at the Standard in Cornhill.

The Standard in Cornhill was the starting point for many of the maps with routes that commenced in London, and after writing the previous post, I wanted to discover a bit more about the Standard, but before I head to Cornhill, here is another of Ogilby’s routes. This one a bit longer than the previous map to Portsmouth.

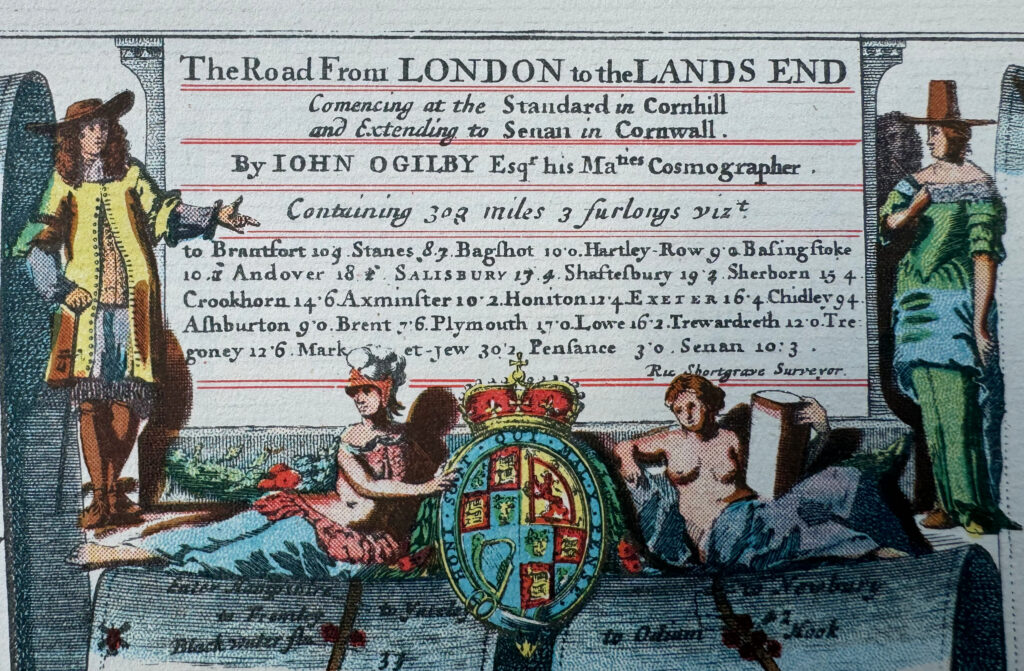

Each of the routes had a header on each page, with the first map having the title of the overall route, total distances, major towns and cities along the route, with individual distances between them.

So if you were planning to journey from the City of London, to Lands End in Cornwall, this was Ogilby’s route, which started with the summary header of the route of 303 miles and 3 furlongs, and started at the Standard in Cornhill:

The first page of the journey to Cornwall, runs from London to just before Winchester, and just after leaving what was then the limits of London, we cross Knightsbridge, when it was still a bridge:

We then cross Hampshire, Wiltshire, Dorsetshire and Somersetshire. In the 17th century, counties still had “shire” at the end of the names such as Dorsetshire and Somersetshire, which would later be shortened, but as with current names such as Wilshire, the “shire” recalls the old origins of these counties and county boundaries:

We then continue travelling through Devonshire, passing through Exeter:

Then head into Cornwall, before finally reaching Lands End, which faces onto “The Western Sea”:

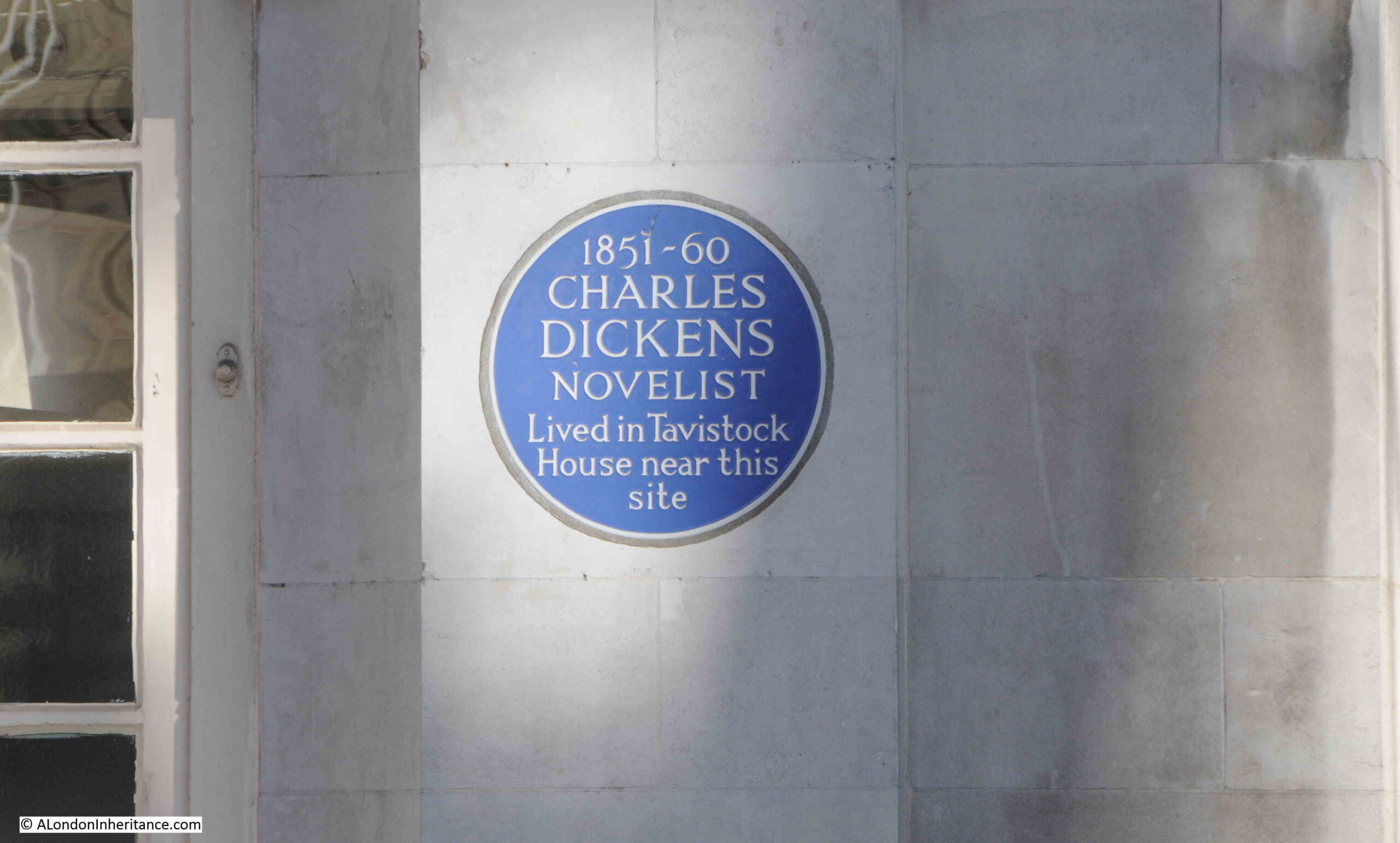

So where was The Standard, the start of the Lands End route, and of many other maps, and what was it? Helpfully there is a City of London plaque to mark the site:

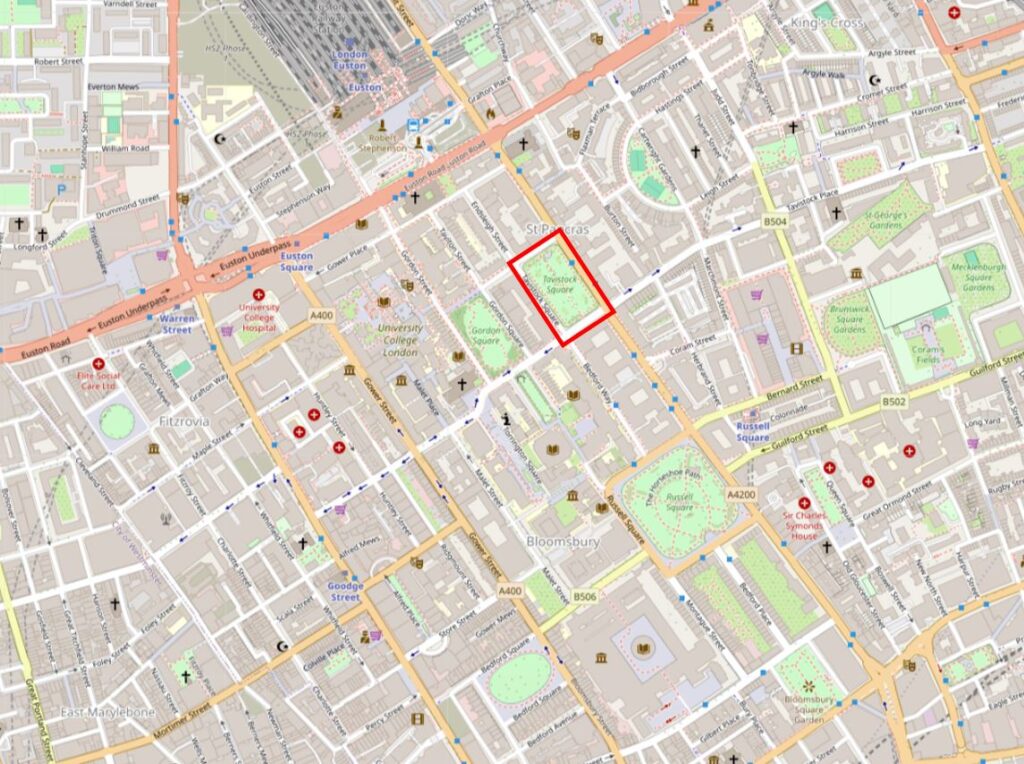

The Standard sounds as if it should have been the name of one of the many large coaching inns across London, and which would make sense as a place where journeys across the country commenced, however it was an ancient well / water pump / conduit, and it was located at a key crossroads in the City of London, where Cornhill, Leadenhall Street, Bishopsgate and Gracechurch Street all meet.

The following photo shows the junction of these four roads:

You can just see the blue plaque, on the first floor of the corner of the white building across the junction. To the right of the white building is Cornhill and to the left is Gracechurch Street. The white building also shows how every bit of available land has been built on in the City, as the building is right up against the church of St. Peter, Cornhill, which has an entrance on Cornhill, and the rear of the church can be seen on Gracechurch Street to the left of the white building.

If we look at the four roads leading from this junction, we can see why this was an important location for travelling out of the City.

Gracechurch Street heads south down to London Bridge, which for centuries was the only bridge across the Thames, and therefore the main route to the south.

Leadenhall Street headed to the east, Bishopsgate headed to the north and Cornhill headed to the west, so from this junction, one could travel to the major routes that ran across the country, and was why maps such as Obilby’s used the Standard as their City of London starting point.

London Past and Present (Henry Wheatley, 1891) provides some background detail about the Standard:

“A water-standard with four spouts made (1582) by Peter Morris, a German, and supplied with water conveyed from the Thames by pipes of lead. it stood at the east end of Cornhill, at its junction with Gracechurch Street, Bishopsgate Street and Leadenhall Street, and with the waste water from its four spouts cleansed the channels of the four streets.

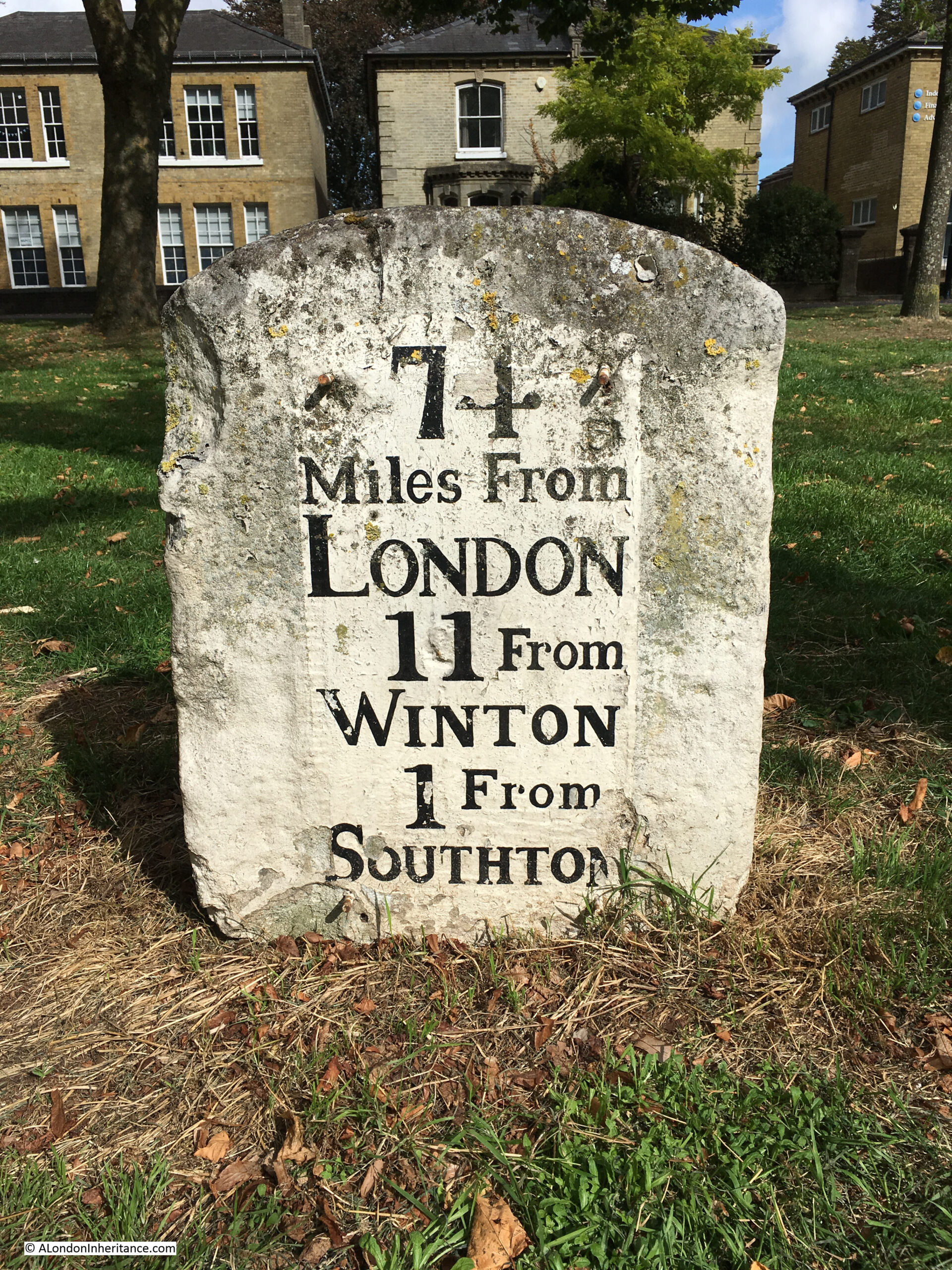

The water ceased to run between 1598 and 1603; but the Standard itself remained for a long time after. It was long in use as a point of measurement for distances from the City, and several of our suburban milestones were, but a very few years ago, and some perhaps are still, inscribed with so many miles ‘from the Standard in Cornhill’. There was a Standard in Cornhill as early as Henry V.”

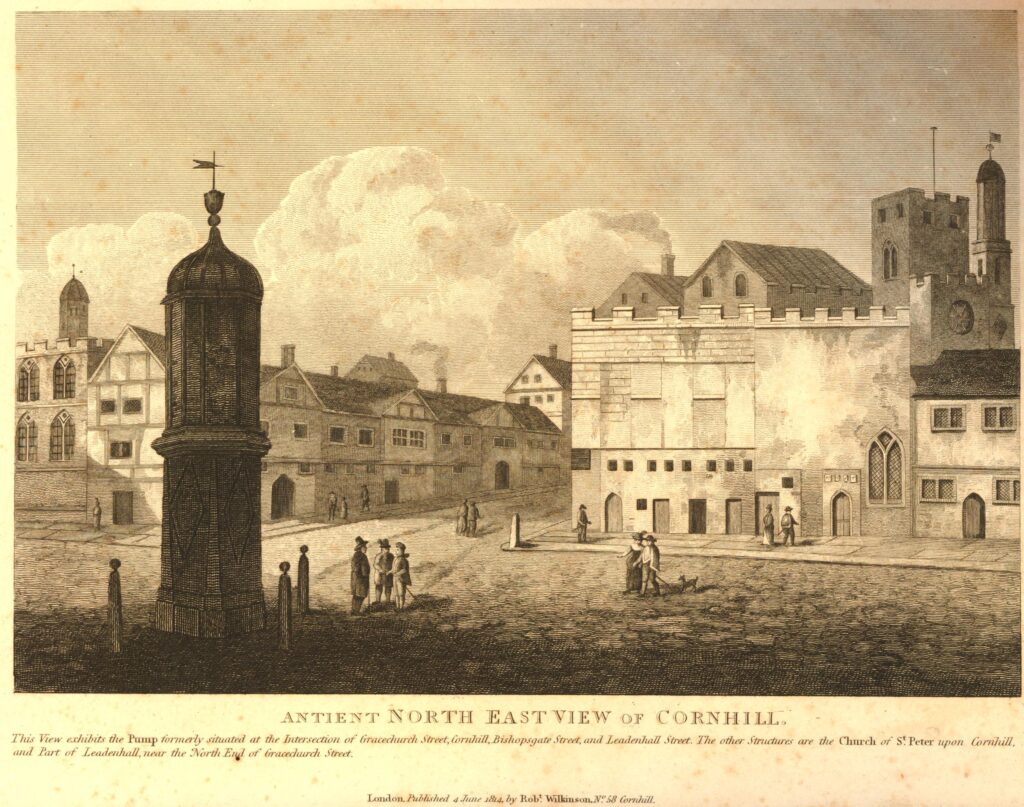

A print, dated 1814 of the “Antient North East View of Cornhill” shows the pump at the crossroads. The print is dated over 100 years after the pump was removed, so whether it was an interpretation of what it may have looked like, or whether it was based on an earlier print is impossible to know:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

London Past and Present, and many other sources date the Standard to around 1582, however the site seems to have been used as a source of water for many centuries before.

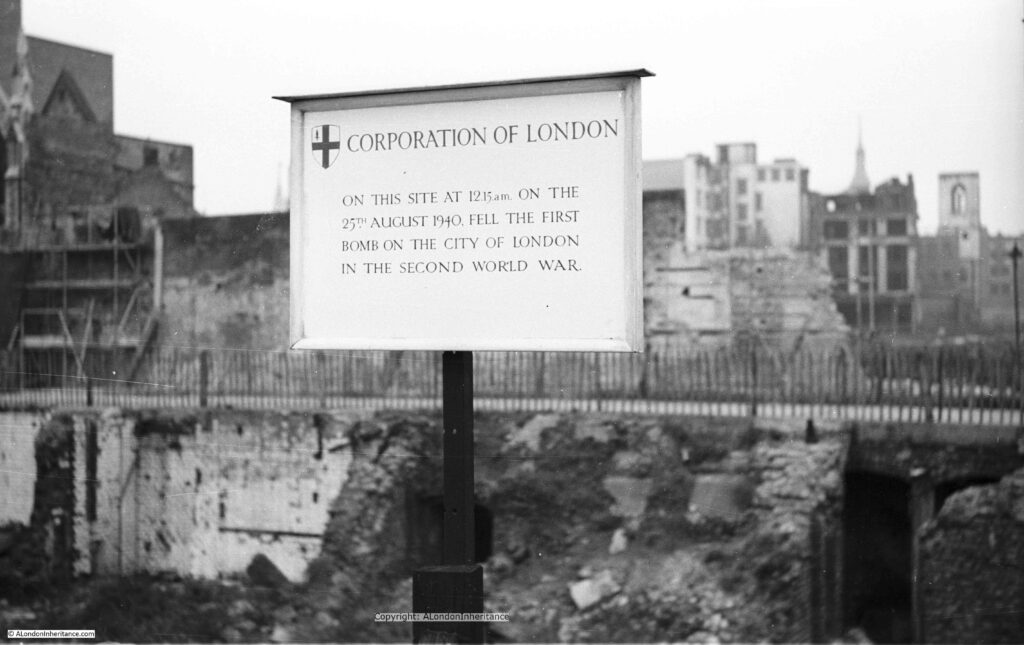

In 1921, as new pipes to carry telephone cables were being laid across the junction, a well which was believed to have been below the Standard was discovered.

Four feet below the 1921 road surface an arched brick top to a brick well of 45 inches in diameter was found. Below this, at 18 feet below street level, a much older well was found, of 30 inches in diameter.

It was believed that this much older well had been filled in, along with part of the upper well, when the water pipes of Morris were installed through an opening in the side of the well.

Excavating the well below the old location of the Standard in 1921.

It was believed at the time that the lower parts of the well dated from early Medieval times, or possibly earlier, but as far I can find, no direct dating evidence was found.

I also cannot find any evidence that the brick and stone structure of the well was removed, so presumably the lower parts of this ancient well are still there, far below the road surface of the junction today.

The plaque mentions that the Standard was removed around 1674, and London Past and Present states that it remained long after water ceased to flow in 1603, and from most of the references I have found, it seems to be that the Standard had become an obstruction at a major road junction. It had long ceased to have any functional purpose and so was simply demolished.

Despite the loss of the Standard at some point in the later part of the 17th century, it continued to be used as a point for measuring distances to and from for many years to come. Not just formal measurements in maps, but also for almost any purpose that required a City of London reference point that would be widely known.

For example, I found the following advert in the Morning Herald on the 4th of January 1838:

“WANTED, a detached FAMILY RESIDENCE, within six miles of the Standard, Cornhill; consisting of drawing and dining rooms, three or four best bedrooms, servants’ rooms, and convenient domestic offices; double detached coach house and stabling lawn, pleasure and kitchen gardens; and if a few acres of meadow land it would be preferred – Apply by letter (post paid) to A.H., 9 Coleman-street, City”

The Standard, Cornhill was often mentioned on milestones when giving a distance to London. There was an 18th century example in Purley for many years. I am not sure if it has survived.

A 1921 article in the Sussex Express mentions the preservation of a milestone in Lewis:

“The milestone let in the upper front of 144/5 High Street, which the Council are to preserve when the building is demobilised, bears the interesting inscription, which probably many Lewes residents have not read; ‘Fifty miles from the Standard in Cornhill, 49 miles to Westminster Bridge, 8 miles to Brightelmstone.”

I have not heard of a building being “demobilised”. I assume it meant being demolished, and the Council did indeed preserve the milestone as it can still be seen in Lewes today, and fortunately I found a photo of the milestone on the brilliant Geograph website:

Credit: Old Milestone by the A277, High Street, Lewes cc-by-sa/2.0 – © A Rosevear – geograph.org.uk/p/6038102

The Standard, Cornhill is just one of a number of locations that have been used as a point from where distances to and from London have been measured.

The most common location seems to be the statue of Charles I to the south of Trafalgar Square, where the Eleanor Cross once stood, so possibly the location of the final cross as part of a 13th century journey to London, still marks where distances are measured to and from:

Plaque by the statue recording that the site of the cross was / is from where distances are measured:

It is fascinating to stand at the eastern end of Cornhill, look across the road junction, and imagine the Standard water pump / conduit that once stood there, and that an ancient well probably still exists deep below the surface.

What I also find fascinating are the stories told by books, not just from their intended contents.

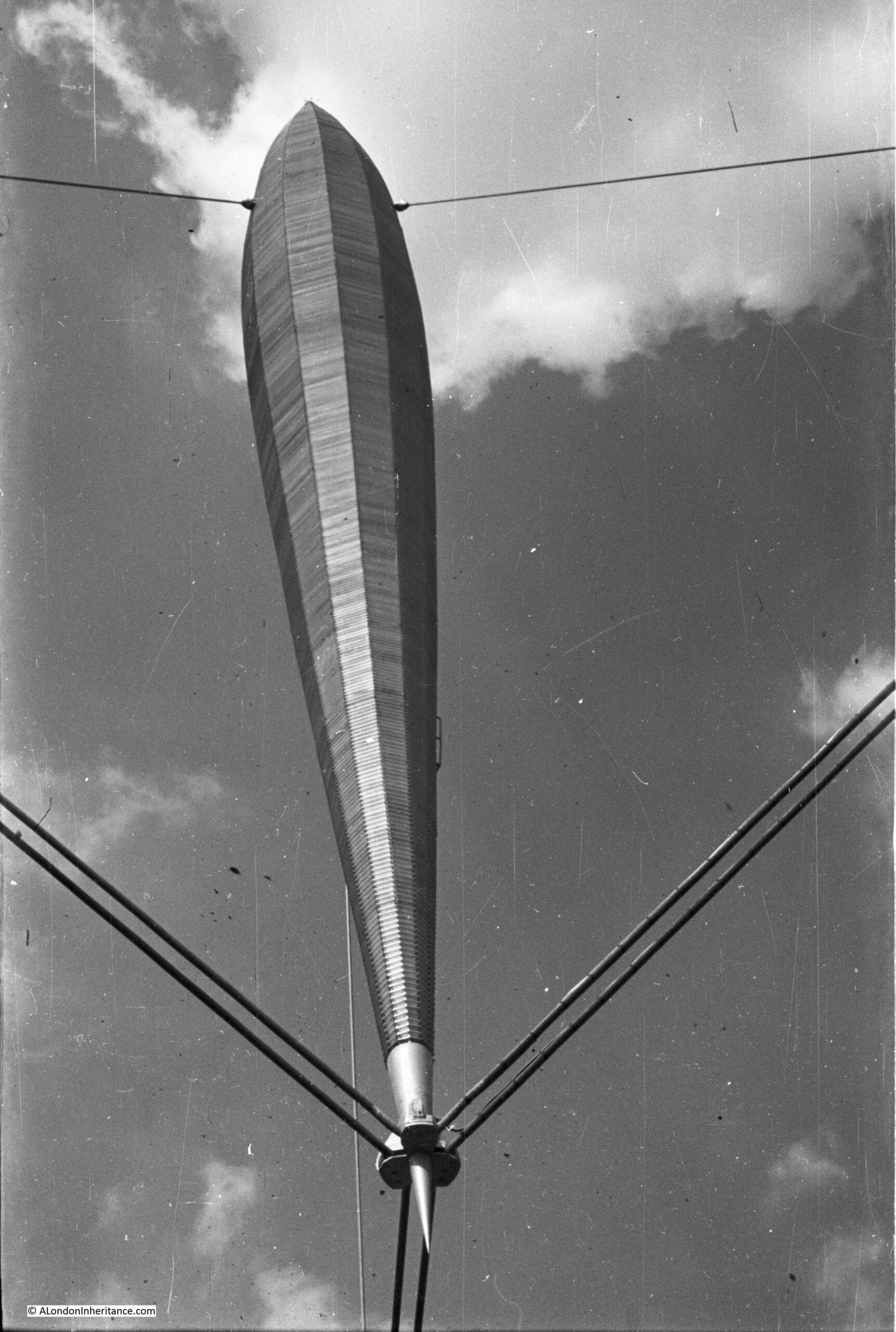

I have a copy of a 1939 facsimile of Ogilby’s Britannia, published by the Duckhams Oil Company on the 7th of December 1939, the 40th anniversary of the company’s founding.

Duckhams had a sales office at Duckhams House, 16 Cannon Street in the City, and the books of the facsimile of Britannia were in the office when war broke out. The company thought that the celebration of their 40th anniversary was a little out of place as war had just been declared.

The books appear to have been stored in Cannon Street for a period, with “two narrow escapes from bombing”, they were then distributed, with a little note in the inside cover:

The PTO reveals a postscript appealing for funds for the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund.

Alexander Duckham, who founded the company, and also signed the note in the book lived for some years at Vanbrugh Castle near Greenwich Park. He must have been a long standing supporter of the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund as in 1920, just a year after the fund had been established, he donated Vanbrugh Castle to the fund, to be used as a school for children of members of the RAF who had been killed in service.

Just some of the obscure connections you can make across London.

From an ancient well and water conduit at an important cross roads in the City, to a map maker who used the water conduit as the starting point for his routes out of London, and to an early 20th century industrialist who loved Ogilby’s maps and published a facsimile from their office in Cannon Street during the last war.

Copies of the facsimile of Ogilby’s Britannia can be found on the Abebooks website, and if you are interested in John Ogilby, the Nine Lives of John Ogilby by Alan Ereira is a really good account, and can be found here.