Bills of Mortality – Death in early 18th Century London. A cheerful subject for a Sunday morning’s post, but a really interesting subject, and one that sheds light on living in London 300 years ago, in the early years of the 18th century.

What were Bills of Mortality? They were lists of deaths in the city, detailing the number that had died by individual cause of death. The majority of deaths were from some form of disease or illness, however the Bills of Mortality also included lists of Casualties – those who had died through some form of accident.

I took a random year in the early 18th century which had a good sample of weekly Bills of Mortality, the year 1721.

So what was happening in 1721?

George I was the monarch, with the country having survived the Jacobite rebellion of 1719 which aimed to restore James Stuart to the throne. Edmond Halley (after whom the comet would be named) was Astronomer Royal. Grinling Gibbons died – his remarkable wood carving can still be seen at a number of sites across London.

The collapse of the South Sea Company, known as the “South Sea Bubble” was in the previous year. One person who made a considerable amount of money from shares in the South Sea Company, and who sold before the collapse of the company was Thomas Guy. In 1721 he founded Guy’s Hospital

In 1721, Robert Walpole became the first Prime Minister.

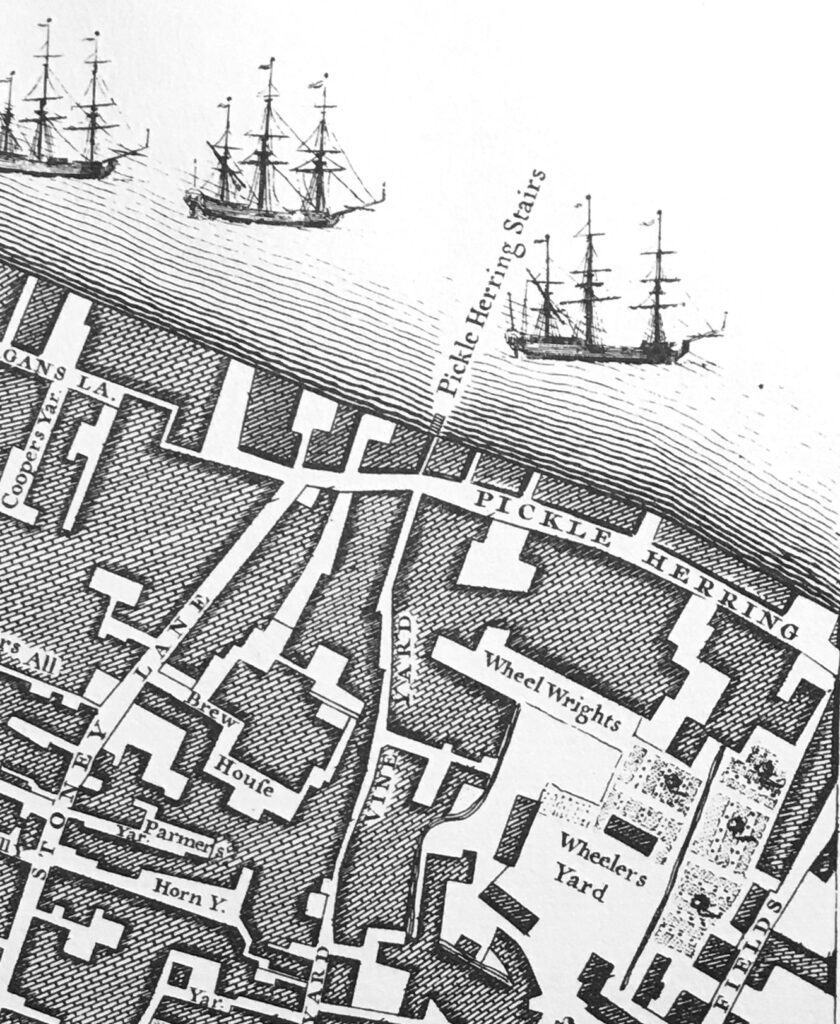

London was expanding rapidly to the north and west, and by 1746, John Rocque’s map would show the new estates north of Oxford Street, and between Oxford Street and Piccadilly.

Executions were still taking place on the Thames foreshore in Wapping for any crimes that carried the death penalty and came under the authority of the Admiralty.

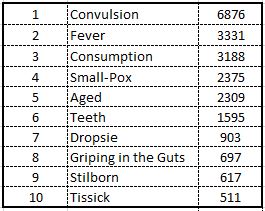

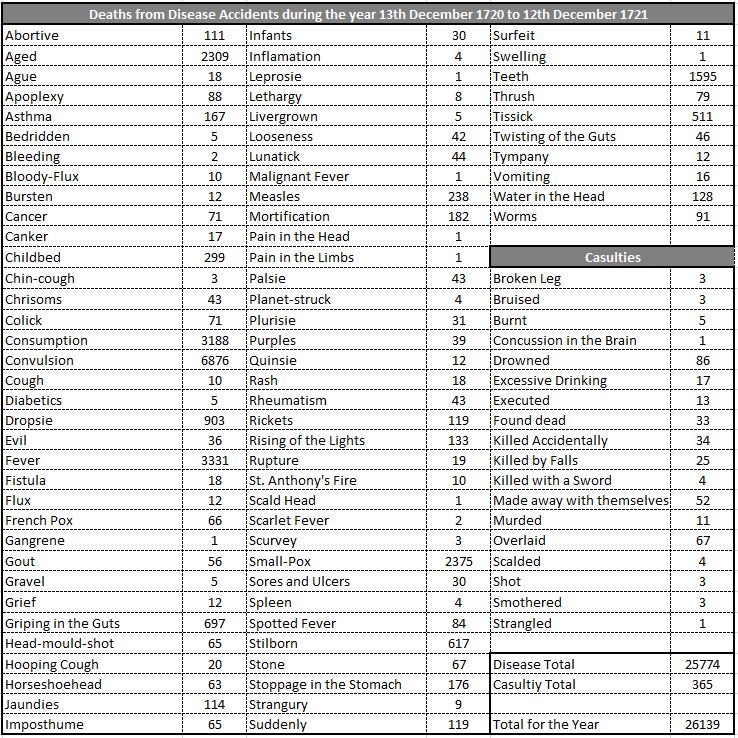

So, with that background, lets have a look at what might have killed you if you were living in London in 1721, starting with a compilation of all the weekly Bills of Mortality for the year:

There is so much to follow-up in these records. Firstly, some of the strange causes of death.

Many of the causes are recognisable today, however some need an explanation, and a sample are listed below:

- Bloody Flux – A horribly descriptive term for Dysentery, which I am surprised was as low as 10 for the year given the polluted state of drinking water in early 18th century London

- Evil – This appears to have been a form of tuberculosis

- French Pox – Syphilis

- Head-mould-shot – An injury or disease of the bones of the skull

- Mortification – Referred to death caused by Gangrene or similar diseases

- Planet Struck – A really strange name. It seems to have been used for a sudden death that some believed had an astrological connection with the planets

- Rising of the Lights – Lights seems to have been a Middle English word for the lungs and rising of the lights refers to some form of lung disease

- St. Anthony’s Fire – This appears to have been horrible. It was caused by eating grains such as rye, that had been infected by a fungus with the name of Claviceps purpurea. Symptoms included a burning feeling in the extremities of the body (hence the use of the word Fire in the name), along with sores, hallucinations and convulsions. St. Anthony comes from monks dedicated to the saint who offered help to suffers.

- Strangury – The symptom of this was painful urination, and the cause was some form of bladder disease

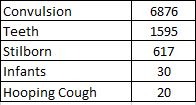

- Teeth – Nothing to do with something being wrong with your teeth, this appears to have been how the death of a child was recorded when they were teething

- Tissick – Death following a cough which must have been due to some form of lung disease

Many of the causes of death had names that described the symptoms or cause of death, and a number of names could all refer to the same cause of death. Some of the names make you wonder how much thought there was into the cause before recording the death.

For example, with some of the deaths with very low numbers, you can imagine the following conversation:

What did he die off?

Don’t know, but he had a pain in the head

That will do, record that as the cause

The total for the table shows that in 1721 there was a total of 26,139 deaths. It is difficult to get an accurate population count for London in 1721, however a number of sources and years either side (1700 and 1750) seem to converge around 650,000 as a good estimate for 1721. Based on this total population, then 4% of the population died in the year.

Comparing this with today, and the data.london.gov.uk site provides a mid year estimate of the population of London in 2020 as 9,002,500 and the annual number of deaths in that year was 58,800. Based on these figures, 0.65% of the population of London died during 2020.

Even with some errors in the above figures, they do show that the ratio of deaths to total population has decreased significantly in the intervening 300 years.

I sorted the table of deaths to show the causes that resulted in the greatest number of deaths, and the following table shows the top ten causes in 1721:

Convulsion caused by far the highest number of deaths with 6871, double the second highest of 3331 Fever deaths.

Convulsion in the early 18th century was not what we would expect today. It was used to describe any general cause of death in infants. It had been replacing “chrisomes” as an archaic term for death in infants. Chrisomes had, and continued for a while, been used to describe the death of an infant under one month of age. The term came from the name of a white linen cloth that was used to cover a baby’s head when baptised, and was also used as a shroud for a dead baby.

There is a chance that some of the deaths recorded as a Convulsion could have been an adult, however if we assume they were all deaths of infants, then sorting the table on child deaths, we get a total of 9,138, or 35% of all deaths attributed to diseases, which just shows that even with a degree of incorrectly recorded deaths, surviving childhood was the greatest challenge of being born in early 18th century London.

The following table shows the causes of death for children:

The risk to life during birth was also to the mother, and in 1721, 299 deaths were recorded as “Childbed”, the cause of which was an infection following birth also known as puerperal fever.

The record for 1761 listed the numbers christened and buried during the year:

- Christened – 18,370

- Buried – 26,142

- Increase in burials this year – 688

These figures show that numbers buried were higher than numbers christened. This could be for a number of reasons:

- Not all children were christened, however I suspect that given the religious and superstitious views of the time, a high percentage of births led to a christening

- Presumably non Christian children were not recorded as being baptised, however the numbers of these was probably low

- The population of London was not dependent on births within the city. There was a high level of immigration to the city from the rest of the country, and from abroad, so many of the deaths were of people who had moved to London

- The fact that the number of burials increased over the previous year of 1720, and buried outnumbered christenings shows the rate at which London’s population was expanding

The high number of burials was also due to the very basic level of medical care during the early 18th century. Poor sanitation, sterile conditions to treat wounds and illnesses, poor diets and quality of food, lack of clean drinking water, cramped living conditions, etc. all contributed to the high rate of death.

People also still believed in many of the superstitions around illness and death, and also in many of the supposed cures that were available. One example of the type of cure widely reported in newspapers is the following from 1722:

“We hear that a few weeks ago, a Spring hath been discovered near a Town called Goring, within 12 Miles of Reading in Berkshire, which hath such virtues in it, that lame people who have made use of it by Bathing, have soon dropped their Crutches. Tis said the Clay there cures old sores and green wounds to admiration, and every one who hath made use of it hath found such relief, that they are constantly setting forth its virtues.”

The weekly Bills of Mortality also listed what were called “Casualties”, and included the cause of death. These casualty lists show the many bizarre causes of death across early 18th century London, and many still recognisable names are listed as the place of death. A sample covering four weeks in 1716:

15th to the 22nd January 1716

- Burnt accidentally at St. Mary Aldermanbury – 1

- Choked with a Horse Bean at St. James Dukeplace – 1

- Hanged himself (being Lunatick) at St. Olaves Southwark – 1

- Killed by the Wheel of a Cart at St. Andrews Holbourn – 1

- Overlaid – 3

Overlaid appears to have been the death of an infant by smothering when a larger individual sleeps on top of them. There are Overlaid deaths almost every week in the Bills of Mortality and were probably caused by parents, or older children, sleeping with infants.

5th to the 12th March 1716

- Bruised at St. Mary Rotherhithe – 1

- Found dead in the Fields at St. Dunstan at Stepney – 1

- Killed by a Blow with a Catstick at St. James Clerkenwell

- Killed by a Sword at St. Martin’s in the Fields – 1

- Overlaid – 1

12th to the 17th June 1716

- Hanged himself (being Lunatick) at St. Peters in Cornhill – 1

- Killed with a Musket Ball at Christ Church in London – 1

- Killed by a Blow with a Stick at St. Mary in the Savoy – 1

- Overlaid – 3

The use of the term “Lunatick” is very problematic. The term was often used for deaths of someone with a mental illness, and for those who had committed suicide when it was assumed that they must have been a “Lunatick” for going through with a self inflicted death.

Also in the above two weeks, there are deaths by a blow, by a sword and by a musket ball, presumably these were all some form of murder / manslaughter.

17th to the 24th July 1716

- Cut his throat (being Lunatick) at St Matthew in Friday Street – 1

- Drowned in a Tub of Water at St. Clement Danes – 1

- Executed – 1

- Hanged themselves (being Lunatick) at St. Stephen Coleman Street

- Hanged themselves (being Lunatick) ay St. Katherine Creed Church

Some of these records cry out for more information. How did someone drown in a tub of water at St Clement Danes? How big was the tub, why could they not get out, were they drunk?

The above week’s record also lists one person as being Executed. Strange that this was recorded as a Casualty, however I suspect there was no other way of recording such a death as the weekly Bills of Mortality tried to capture all the deaths in the city.

London’s population and deaths were the subject of a fascinating little book published in 1676 and today a copy is held in the Wellcome Collection. “Natural and Political Observations Mentioned in a following Index and made upon the Bills of Mortality” by Capt. John Gaunt, Fellow of the Royal Society.

John Gaunt writes that he was born and bred in the City of London, and complains that the Bills of Mortality were only used to see how burials had increased or decreased, and for the rare and extraordinary causes of death within the Casualties.

In the book he makes 106 observations on births, deaths, sickness, disease, how information in the Bills of Mortality was used, London’s population, comparison between the City and Countryside etc. The book is a fascinating window on the late 17th century, and explains much of what we see in the 1721 Bills of Mortality.

His observations are really interesting, and I have listed a few of them below:

- The Occasion of keeping the account of Burials arose first from the Plaque, Anno 1592

- That about one third of all that were ever quick die under five years old, and about thirty six per Centum under six (this aligns with the figures for the deaths of children in the 1721 statistics)

- That not above one in four thousand are Starved (so food is generally available and affordable to the vast majority of London’s population, although very many probably only just had enough)

- That not one in two thousand are Murdered in London (the statement appears to be written as a positive, however compared with today, and the figure for 2020 / 21 was 13.3 per million in London, which is considerably better than 1676)

- That few of those, who die of the French-Pox are set down, but coloured under the Consumption (this implies that deaths from Syphilis were considerably under-reported. Perhaps the family of the person did not want it known that they had died of a sexually transmitted disease)

- That since the differences in Religion, the Christenings have been neglected half in half (so there were religious differences resulting in the number of Christenings not being representative of the total number of births)

- That (be the Plague great or small) the City is fully re-peopled within two years (so even after the worse years of the plaque there were enough people moving into the City to restore the population)

- The Autumn is the most unhealthful season (something’s do not change)

- That the people in the Country double by Procreation but in two hundred and eighty years, and in London in about seventy. Many of the Breeders leave the Country, and that the Breeders of London come from all parts of the Country, such persons breeding in the Country almost only were born there, but in London multitudes of others (Women of child bearing ages, and their partners moved in numbers from the Country to the City)

- That in London are more impediments of Breeding than in the Country (interesting comparison with today with possibly wages, need to work, availability and cost of housing all playing a part)

- Physicians have two Women Patients to one Man; and yet more Men die than Women (again, something’s do not change – men do not like going to the Doctor)

- In the Country but about one of fifty dies yearly, but at London one of thirty (so London was not as healthy as the Country, and was getting worse as confirmed by:)

- London not so healthful now as heretofore

John Gaunt published his findings 346 years ago, but it is interesting how many can still apply to London today.

Gaunt was a fascinating individual. He was a Haberdasher by trade, but had a considerable interest in how the collection of data, the use of mathematics and the statistical modelling of data could reveal what was happening to the health of those living in the city, and to population numbers.

He was one of the first demographers – the statistical study of populations.

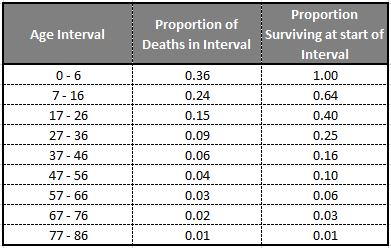

As well as the investigations that led to the observations listed above, he also collected data to help understand life expectancy. The Bills of Mortality did not report age, just the numbers dying of specific causes, so Gaunt had to collect this data through further investigations. This work resulted in the following table:

The middle column shows the proportion of London’s population that could be expected to die within the age interval in the first column, so out of 100 people between the ages of 0 and 6 years, 36 could be expected to die.

The column on the right is the proportion surving at the start of the interval, which is why the first entry is 1, as this represents the full popoulation at birth. It then shows the numbers surviving at the start of the interval, so at age 7, 64 out of the original 100 would be alive. At age 16, 40 out of the original 100 would still be alive, and so on through the age intervals.

The table really shows the young age of London in the years around 1676, as by the age of 27, only 25 out of an initial 100 people would still be alive, and at age 57, this would be down to 6 out of the original 100.

A morbid subject, but it does show that in the 17th century and early 18th, the data was available to start understanding disease and death in the City, and people like John Gaunt were beginning the process of understanding how to use and apply this data.

This would be a very long process, as even by 1854, Dr. John Snow was still facing challenges when he used data to demonstrate that a Cholera outbreak in Soho could be traced to a specific water pump.

What is also clear is that if you had made it into your 20s, you were very lucky as only 25% would make it to the age of 27. There were a large number of terrible diseases just waiting to pick you off, and just living in London would also put you at risk of becoming a casualty of any number of possible accidents.

However despite all these challenges, the population of London kept growing.