Walk up St John Street, north of Smithfield, and turn up St John’s Lane towards St John’s Gate, and on the left you will find Albion Place. My father’s 1947 photo of the street shows a pedestrianised street with a row of terrace houses. In the distance the street descends rapidly towards Farringdon Station, the descent of the street indicating that this was once down to the valley of the River Fleet.

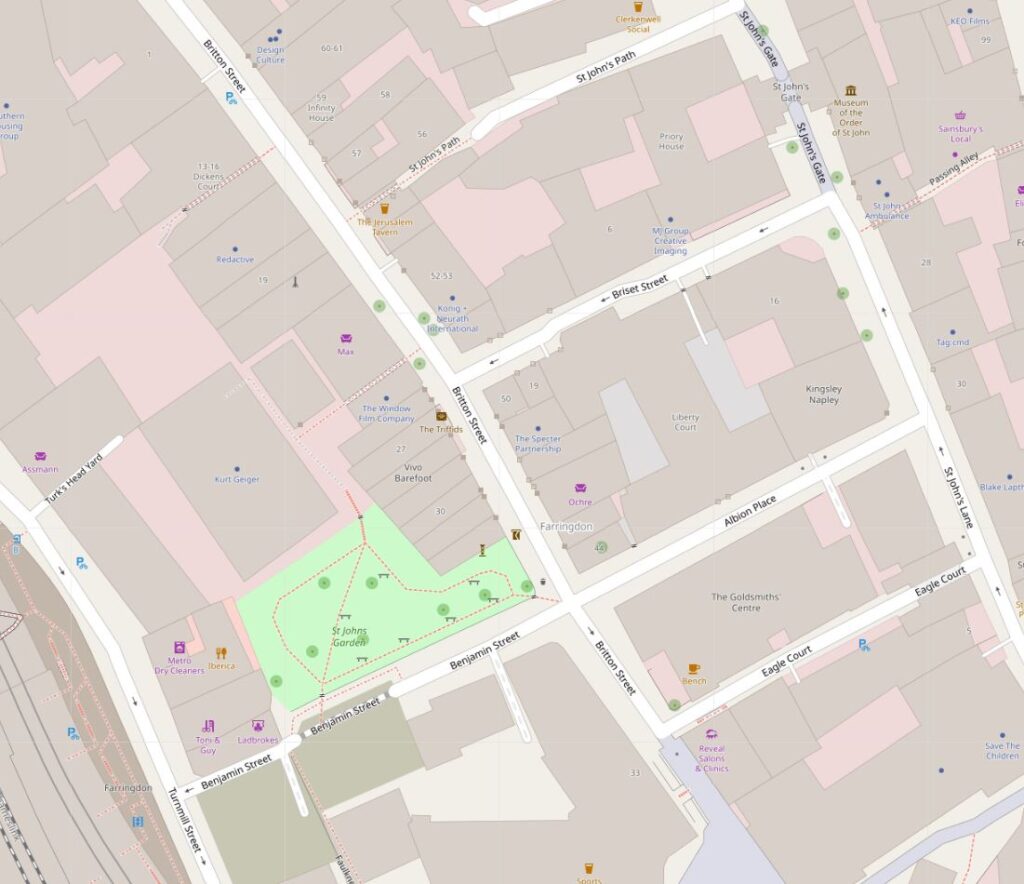

Albion Place in 2020:

The name Albion Place was in my father’s notes to the strip of negatives which included this photo. I was concerned whether this was indeed the right location. Apart from the way the street descends, there are no other visual clues. All the buildings in the 1947 photo have since been demolished. Albion Place is no longer pedestrianised, and the street today looks wider than it appeared in 1947.

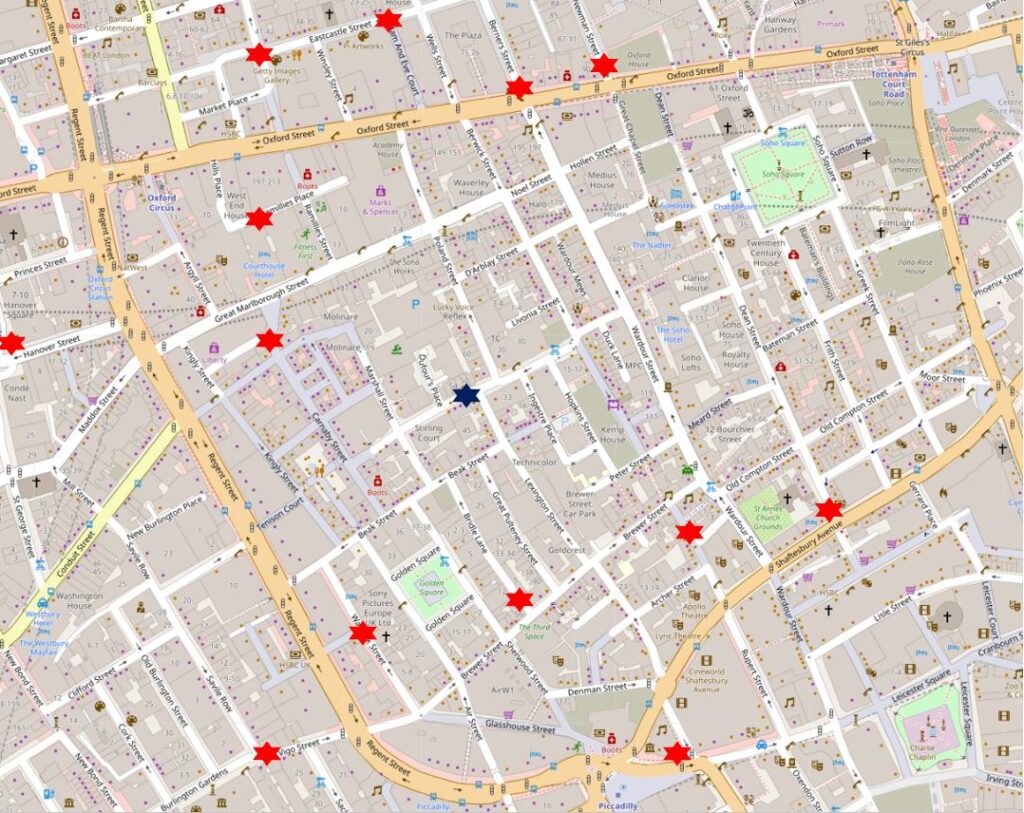

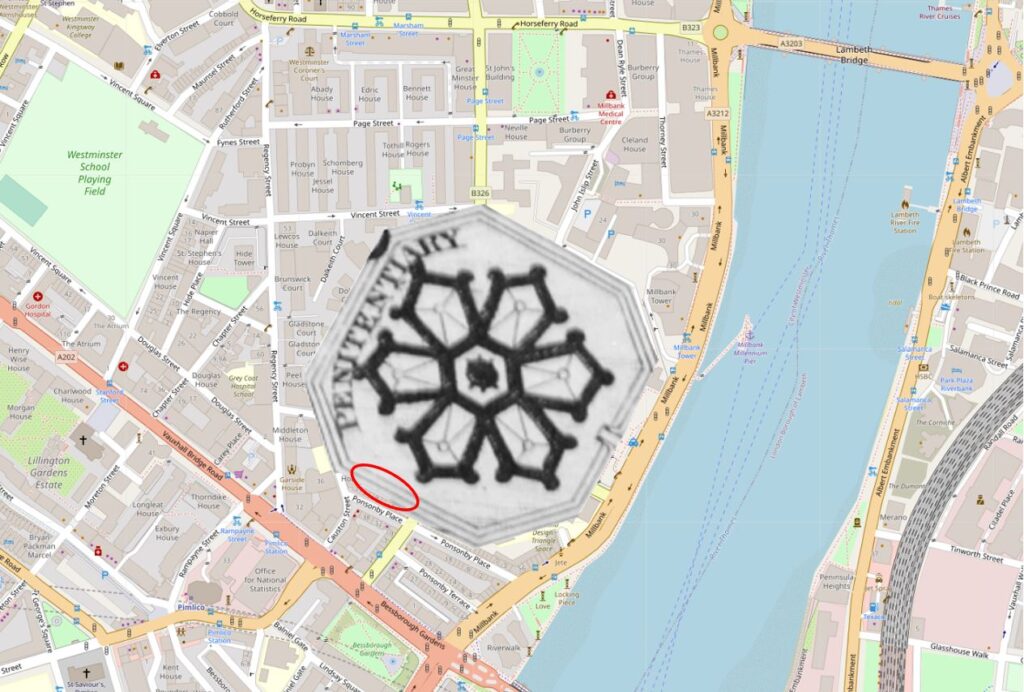

Albion Place is shown in the lower right of the following map, between St John’s Lane and Britton Street. Benjamin Street then continues on towards Turnmill Street and the tracks of the railway into Farringdon Station (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The main cause of my doubt about the location was the junction with Britton Street. This is on the right, at the end of Albion Place, just before Benjamin Street descends towards Farringdon.

The junction with Britton Street cannot be seen in my father’s photo – indeed the street appears to be a continuous row of buildings.

I have been able to confirm this is Albion Place through a single visual clue, as well as a couple of other pointers.

Firstly, towards the end of Benjamin Street, there is a building that juts out and narrows Benjamin Street towards the junction with Turnmill Street.

The building has a unique outline. Today, a tree has grown up against the building and hides the edge of the wall and roof:

However I can demonstrate this is the same building as one seen at the very end of the 1947 photo.

In the photo below, on the left, is an enlargement from my father’s photo showing the very end of the street. There is a building jutting out and I have outlined in red the shape of the upper wall, up towards the roof.

In the photo on the right, I have marked the same outline of upper wall and roof.

The two buildings both edge out into Benjamin Street, and both appear to have the same upper wall and roof shape. Would be clearer without the tree, but they appear to be the same.

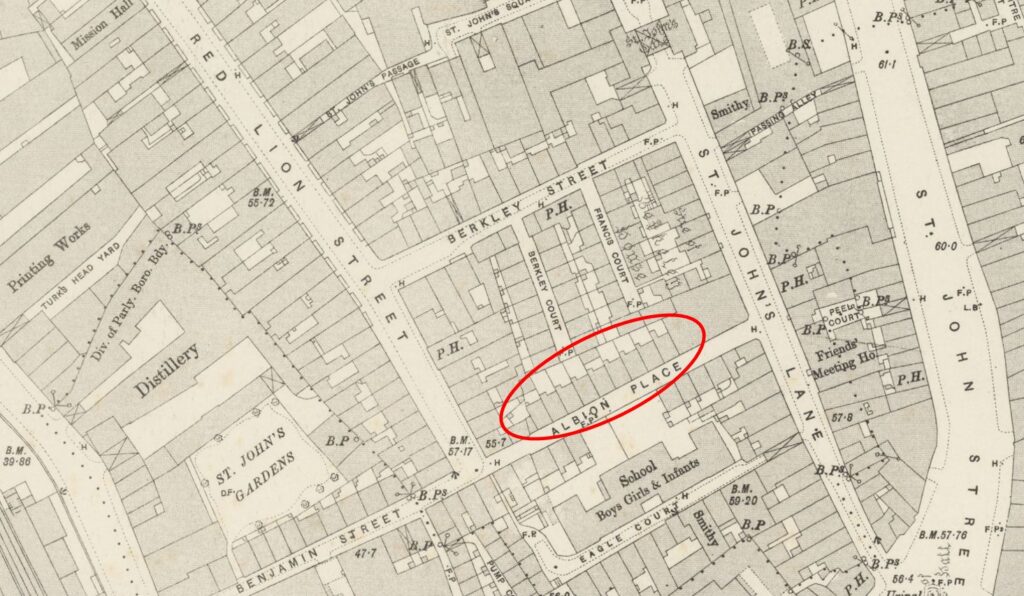

I also checked the 1894 Ordinance Survey map, and in Albion Place, there is a row of terrace houses in exactly the right place (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’):

The OS map also shows Britton Street (then Red Lion Street) and the junction with Albion Place. I have no idea why this does not appear in my father’s 1947 photo, I assume the junction is there – just the perspective of the photo, and the way the buildings line the route of Albion Place and continue straight down to Benjamin Street.

I found one final confirmation of the location. The London Metropolitan Archives, Collage Collection has a single photo of Albion Place, dated 1956 which although photographed in the opposite direction towards St John’s Lane, includes a view of the same terrace.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01 080 56 4132

The houses look the same, even the house on the left having the two steps to the door, with single steps serving the rest of the houses – exactly the same as in my father’s photo.

In the 9 years between the two photos, Albion Place has lost the rather nice lamp posts. In 1956 a new concrete lamp post is in place.

The following photo is looking up Albion Place from the junction with Britton Street, and shows the same building at the end of the street, on St John’s Lane, as in the Collage photo above.

Albion Place has a long history. The land was originally part of the outer precinct of the Hospitallers’ Priory of St John of Jerusalem, which extended down to Cowcross Street by Smithfield Market, Turnmill Street to the west and St John (‘s) Street to the east.

The street seems to have been built in the late 17th century, and was probably part of the gradual growth of the City northwards, as housing and industrial premises were built over what had been the lands of St John’s Priory.

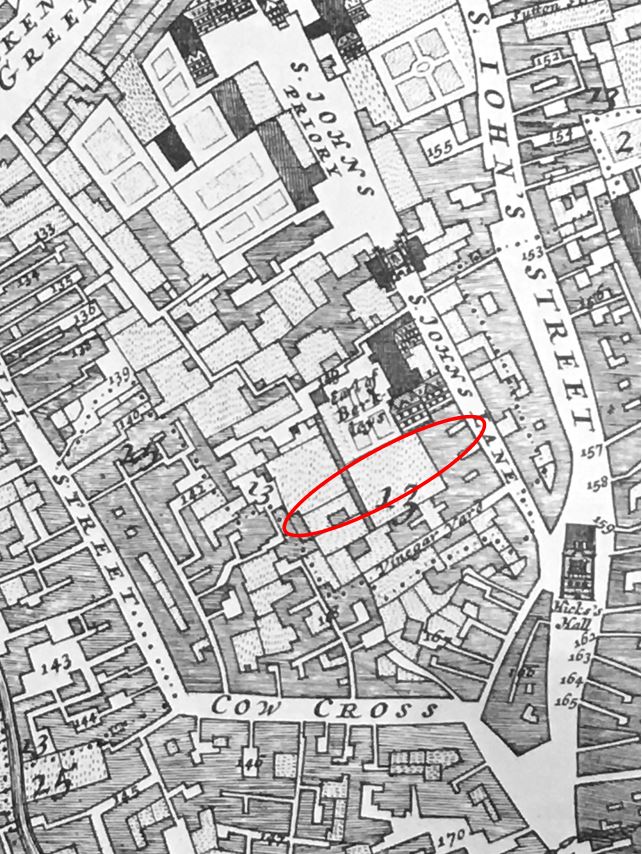

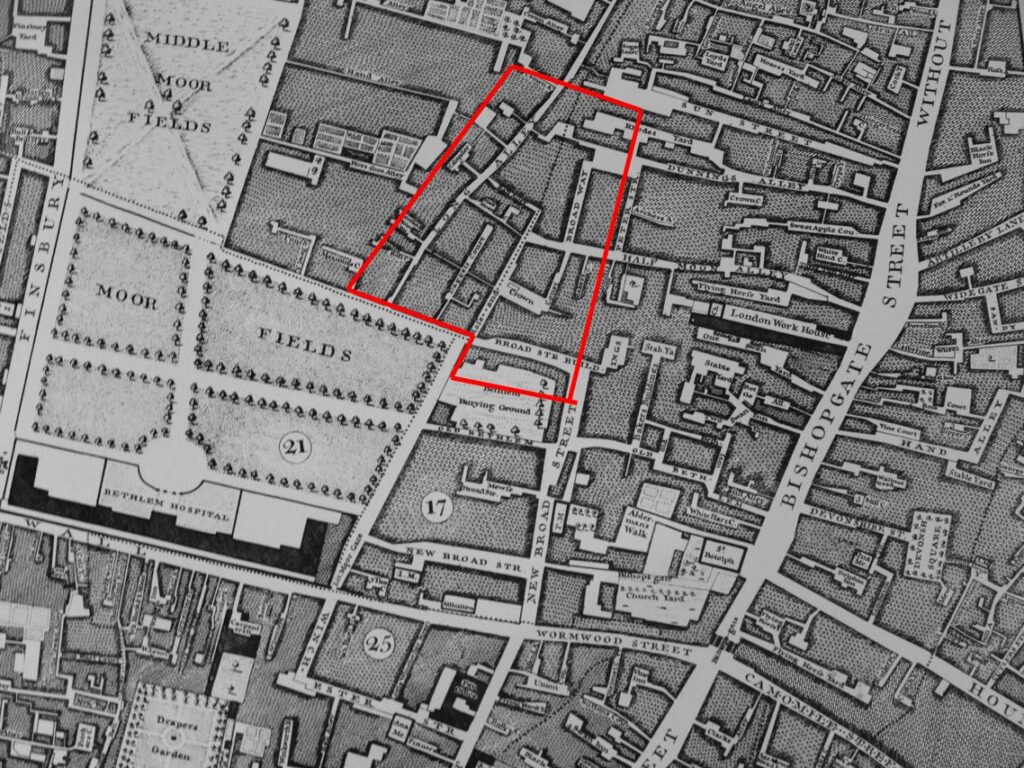

The following map extract from William Morgan’s 1682 map of London shows the area as it was with the location of Albion Place marked by the red oval, on space then occupied by what appears to be the Earl of Berkleys property.

When built, the street was originally called George’s Court, and had changed name to Albion Place by 1822 when the court had been rebuilt to the form seen in my father’s photo, and is presumably from when the terrace of houses date.

The growth of Clerkenwell was linked to industries such as watch and clock making and Albion Place was home to the inventor of an alloy which would reduce the price of ornate 18th century clocks.

Gold was originally sold as 18 carat standard, and was therefore expensive when used as the casing for a clock or watch. Christopher Pinchbeck, who lived in Albion Place invented an alloy of copper and zinc which very nearly resembled gold. Pinchbeck moved from Albion Place to Fleet Street in 1721.

The name “Pinchbeck” was given to this new alloy, which was widely used for the cases of clocks and watches up until the mid 19th century when the sale of lower carat gold was legalised.

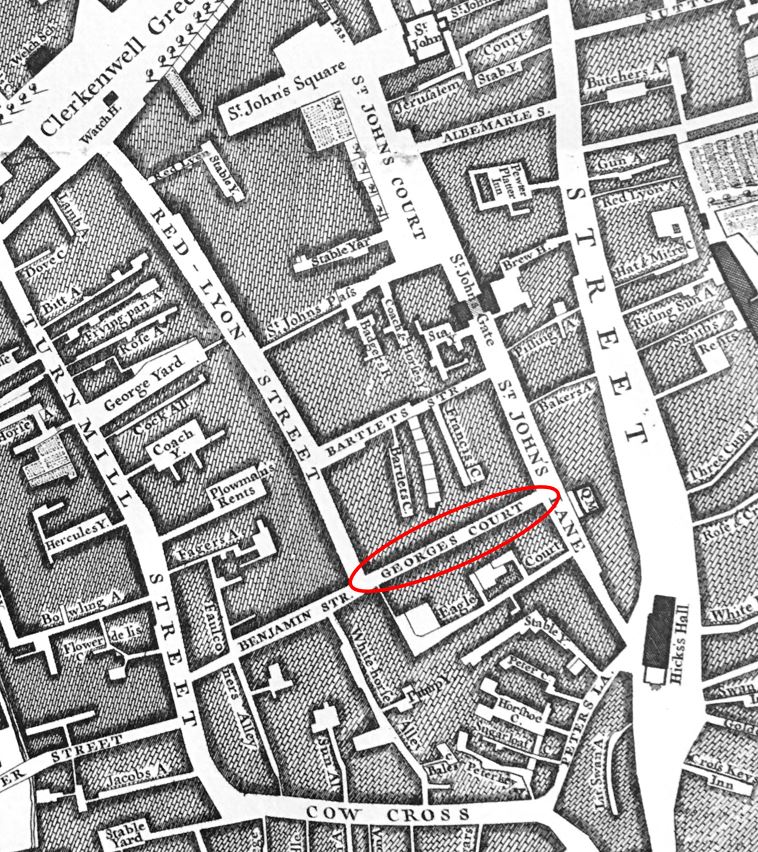

By the time of Rocque’s 1746 map of London, the street that would become Albion Place was now shown on the map as George’s Court. Benjamin Street had also been built down to Turnmill Street.

The following photo shows Benjamin Street. Albion Place has a shallow reduction in height, which is far greater in Benjamin Street, as the land descends to what was the Fleet valley which ran just across the railway tracks into Farringdon Station, roughly along the route of Farringdon Road.

The following photo shows the view along Britton Street – the street originally named Red Lion Street. This is the junction that caused me to doubt whether the photo was of Albion Place as it could not be seen in my father’s photo.

View back up Benjamin Street and Albion Place. To the north of Benjamin Street (to the left in the following photo) is a small green space – St John’s Gardens.

St John’s Gardens was originally the burial ground of St John’s Church – the parish church that was in St John’s Square, and following wartime bombing, now rebuilt as the Priory Church of the Order of St John.

The area was taken on by the parish in 1754 and used until 1853 when it was closed under the Burials Act. The burial ground originally did not face directly onto Benjamin Street. As shown in the 1894 OS map earlier in this post, a line of buildings ran along Benjamin Street with St John’s Gardens being an enclosed square. This can also be seen in the 1947 photo where buildings line the far end of the street.

Today, the gardens form a valuable bit of green space.

There is a rather poignant mural in the gardens.

It was created by Emma Douglas in memory of her son Cato Heath who died aged twenty one in 2010. Each coloured rectangle represents a day in the life of her son, with the colour of the rectangles representing an event, for example a black rectangle for a doctor’s appointment.

The mural created by Emma in St John’s Gardens is one of a number to be found.

On the corner of Albion Place and Britton Street is a rather interesting building:

This is the Grade II listed 44 Britton Street originally built for Janet Street-Porter and designed by Piers Gough.

Before her career in the media, Janet Street-Porter trained at the Architects Association where she met Piers Gough. She wanted a house that did not follow the old English tradition with rooms being in well defined places. She also wanted a house that did not look too friendly and looked a bit hostile, so there is no outward facing door to the building. The entrance is tucked away at the rear of the building in a courtyard.

The bricks used in the construction are shaded, starting with dark bricks at the base, getting gradually lighter towards the top of the walls. This was to give the impression that the base of the building is in shade, with the top of the building in perpetual sunlight.

The external lintels above the windows are in the shape of concrete logs.

Janet Street-Porter lived in the house from 1988 to 2001. There is an episode of the BBC programme Building Sights dating from 1991 with Janet Street-Porter talking about, and showing the interior of the building. The programme can be found on the BBC iPlayer here – it is worth a watch.

On the opposite corner of Albion Place and Britton Street there is another interesting building. This is the Goldsmiths Centre:

The Goldsmiths Centre was founded by the Goldsmiths Company, one of the twelve great livery companies of the City of London, as a charity for the professional training of goldsmiths.

The centre provides a location where the technical skills of gold and silversmithing and jewelry working can be taught and developed. The building also provides support for developing business, with shared studio space in which to work.

The Goldsmiths Centre is in a rather appropriate location given the history of Clerkenwell with the trades associated with metal working.

The Goldsmiths Centre was opened in 2012. The building on the Albion Place corner is a modern addition to a Grade II Listed 1872 Victorian London Board School, which together form the Goldsmiths Centre.

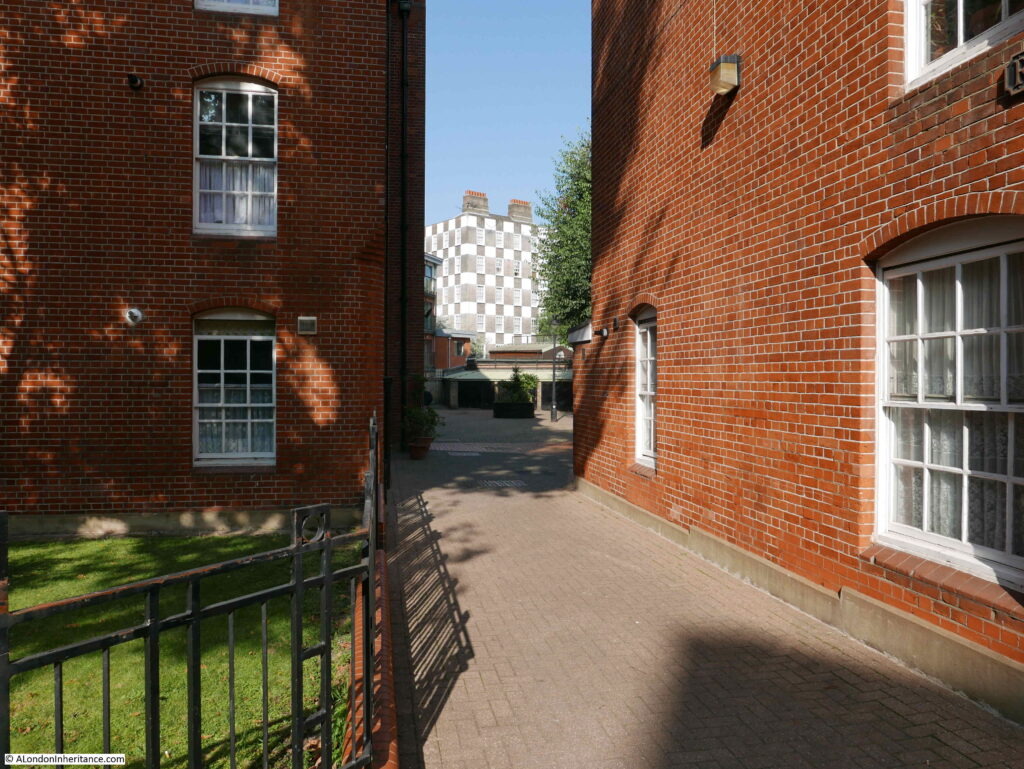

The main entrance to, and the main school building is in Eagle Court which runs from Britton Street back up to St John’s Lane.

Eagle Court is shown in Rocque’s map, and in the earlier 1682 map by Morgan appears to be shown as Vinegar Yard, so Eagle Court is older than Albion Place.

The name Eagle Court comes from Eagle’s House which appears to have been a mid 14th century mansion built along the western edge of St John’s Lane. The house was named after the Templar preceptory of Eagle in Lincolnshire and acted as the Clerkenwell residence of the bailiff as the senior official of this preceptory.

The view up Eagle Court towards St John’s Lane:

Before the school was built, Eagle Court had long been a dense court of workshops and houses. Industrial processes being performed next to living space.

Work was dangerous and accidents were frequent. for example on December 5th, 1738 “A fire broke out in the workshop of Mr Tabery, a Japanner in Eagle Court, St John’s Lane, occasioned by the Varnish Pot boiling over. Two men were so miserably burnt that their lives are despaired of”.

The area around Albion Place and Eagle Court was densely populated and criminality was rife. The location for the school was chosen by the London School Board for this very reason, as introducing a formal education was seen as one of the means to improve the future prospects of the residents.

When the school was being built in 1873 and 1874, the workmen and the location needed a police guard to protect them and the building materials for the school from the lawless elements of the local population.

The school backs onto Albion Place, and is often referred to as being in Albion Place. The following article from April 1906 provides another example of the crime in the area which was probably heightened by the precious metals which could be found in the workshops:

“DESPERATE BURGLARS – SCHOOL CARETAKER ATTACKED WITH JEMMY. The caretaker of the London County Council School at Albion Place, Clerkenwell, was found lying in a pool of blood with his head severely cut on Saturday night under mysterious circumstances.

When the premises next door were opened the ground floor window was found to have been forced and the entire premises ransacked. The second floor was occupied by a gold refiner. Several hundred pounds worth of gold and silver were on this floor, and the men removed a considerable quantity.

It was when the burglars were leaving via the schoolyard that they were surprised by the caretaker. He was rendered unconscious by blows from a jemmy, which the men dropped.

The caretaker has not yet been able to give any account of the affair. The burglars worked leisurely, and cleaned the window before leaving to remove all traces of incriminating finger prints”.

The increasing level of workshops and industry in the area resulted in the reduction of family homes and the number of children resulting in the closure of the school in 1918.

For the rest of the 20th century, the old school buildings hosted a wide range of educational functions including Cordwainers’ Technical College, the LCC Smithfield Institute and Smithfield College of Food Technology, the College of Distributive Trades, and following a merger with the London College of Printing, the old school buildings became the London Institute.

The current use of the building as the Goldsmiths Centre therefore continues a long educational tradition, including a century of use as a technical educational centre.

Unlike many buildings created by the London School Board, the building consists of only two floors. This was intentional so as not to cast the buildings opposite in this narrow street, in permanent shadow,

I have walked just a few short streets, down Albion Place, along Benjamin Street, then back up to St John’s Lane via Eagle Court, but these few streets reveal their part in the long history of Clerkenwell. From the Priory of St John of Jerusalem, through the industrialisation of the 18th and 19th centuries when the area was home to watch, clock and metal working, an area of dense population with high levels of crime.

The terrace shown in my father’s photo survived until the late 1960s. If the terrace had been renovated, and if Albion Place had stayed a pedestrianised street, with bollards and cast iron lamps, this could have been a lovely street. Although, we always need to be careful when looking back at the past, and remember the lessons of Christopher Pinchbeck’s alloy that all that glitters is not gold.