I have written a number of posts about the City of London blue plaques that can be seen along the street of the City, however there are also many more interesting plaques that tell an aspect of the City’s history, so starting with this post, I am expanding the scope of this occasional series.

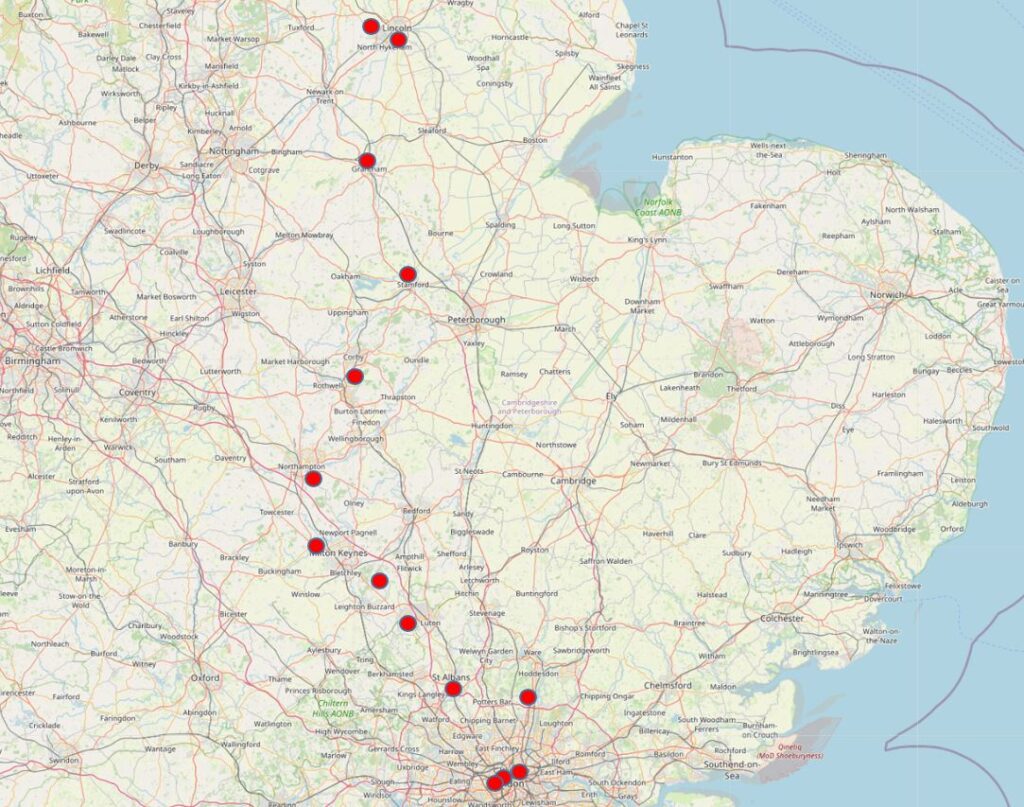

I have also created a map which shows all the City plaques that I have so far covered, with links to the relevant post. The map can be found here.

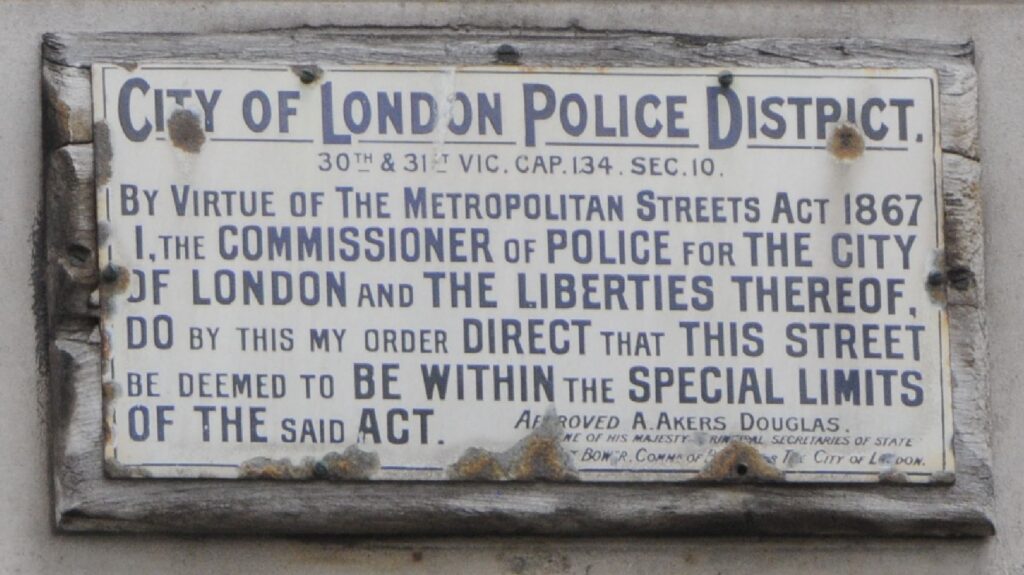

City of London Police District – Princes Street

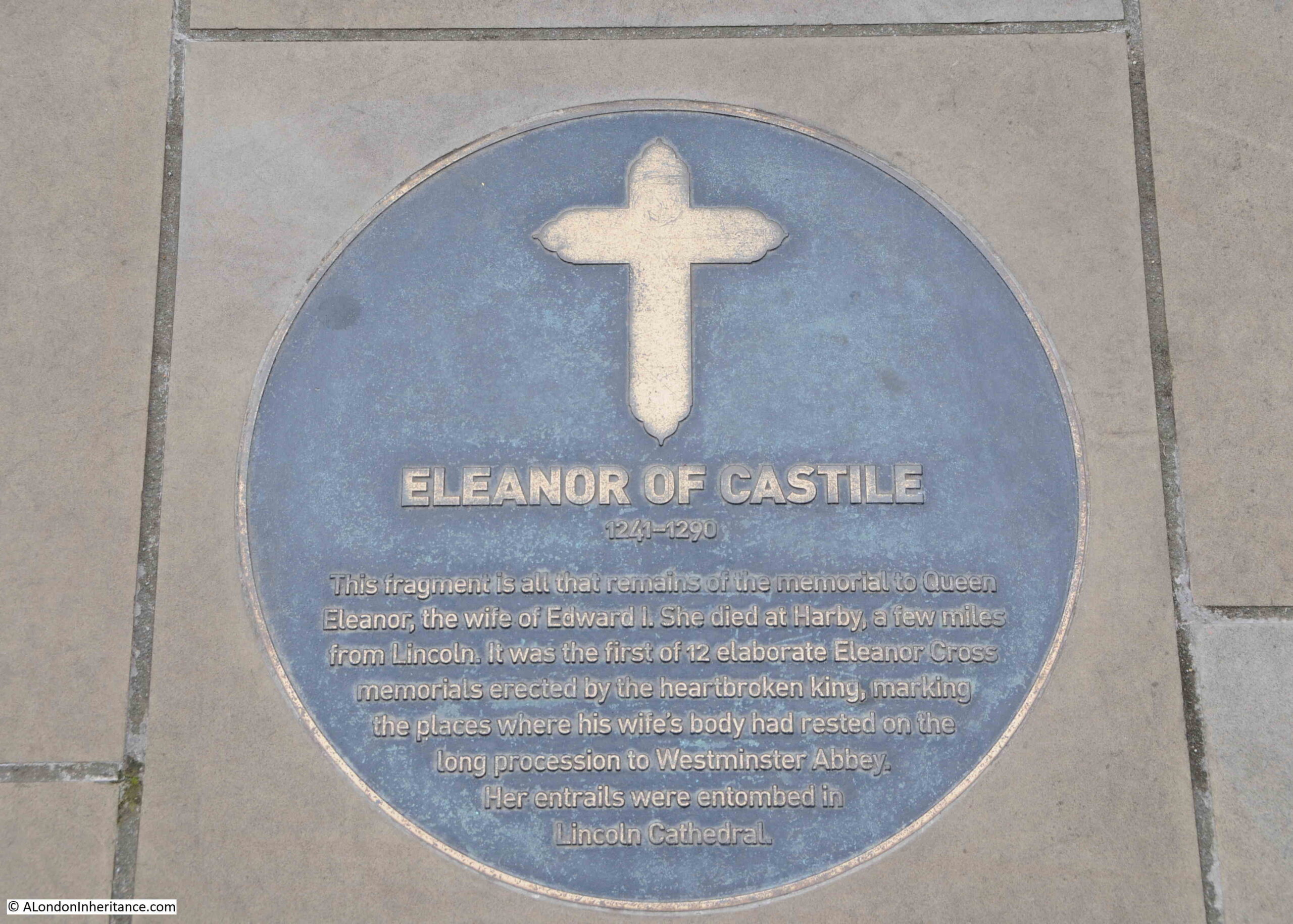

I am starting with what appears to be a remarkable survivor that can be seen just above the entrance to the Bank Underground Station on Princes Street:

The plaque states that the street is deemed to be within the special limits of the Metropolitan Streets Act of 1867:

The Special Limits were powers granted by the act to Police Commissioners, allowing them to set or amend regulations on vehicle traffic along the street, as well as what could be loaded and unloaded along the street, and which could have blocked footpaths. These regulations usually applied for the majority of the working day, and presumably were intended to avoid too much traffic or activities that could have slowed down both traffic and pedestrians.

For Special Limits to apply, the Police had to advertise the fact at the street, ten days before they came into force, so presumably the sign is one of these advertisements that the Special Limits of the Act would apply to Princes Street.

The Act dates from 1867, but I was interested in the date of the plaque.

For Special Limits to apply, the City of London Police would have needed the approval of a Secretary of State, and at the bottom of the plaque is the name of A. Akers Douglas, stating that he approved the request and that he was a Secretary of State.

This was Aretas Akers-Douglas, 1st Viscount Chilston, who was Home Secretary between 1902 and 1905.

To confirm this date, there is the name of Bower at the bottom of the plaque, and although this line of text is damaged, he is listed as a Commissioner of the City of London.

Bower refers to William Nott-Bower who was Commissioner of the City of London police from 1902 to 1925, so his first years in this role align with the time that Akers-Douglas was Home Secretary, so the plaque dates from between 1902 and 1905.

It is remarkable what this plaque has seen. The Imperial War Museum archive includes a photo of bomb damage at the Bank road junction on the 11th of January 1941 when a bomb crashed through the road and exploded in the booking hall of the underground station.

The photo is not one of those that are downloadable and able to be reused on non-commercial sites, so a link to the photo is here.

Look to the left edge of the photo, and on the wall of the Bank there appears to be a couple of signs, one at the correct place and size to be the sign we see today.

It is a remarkable survivor.

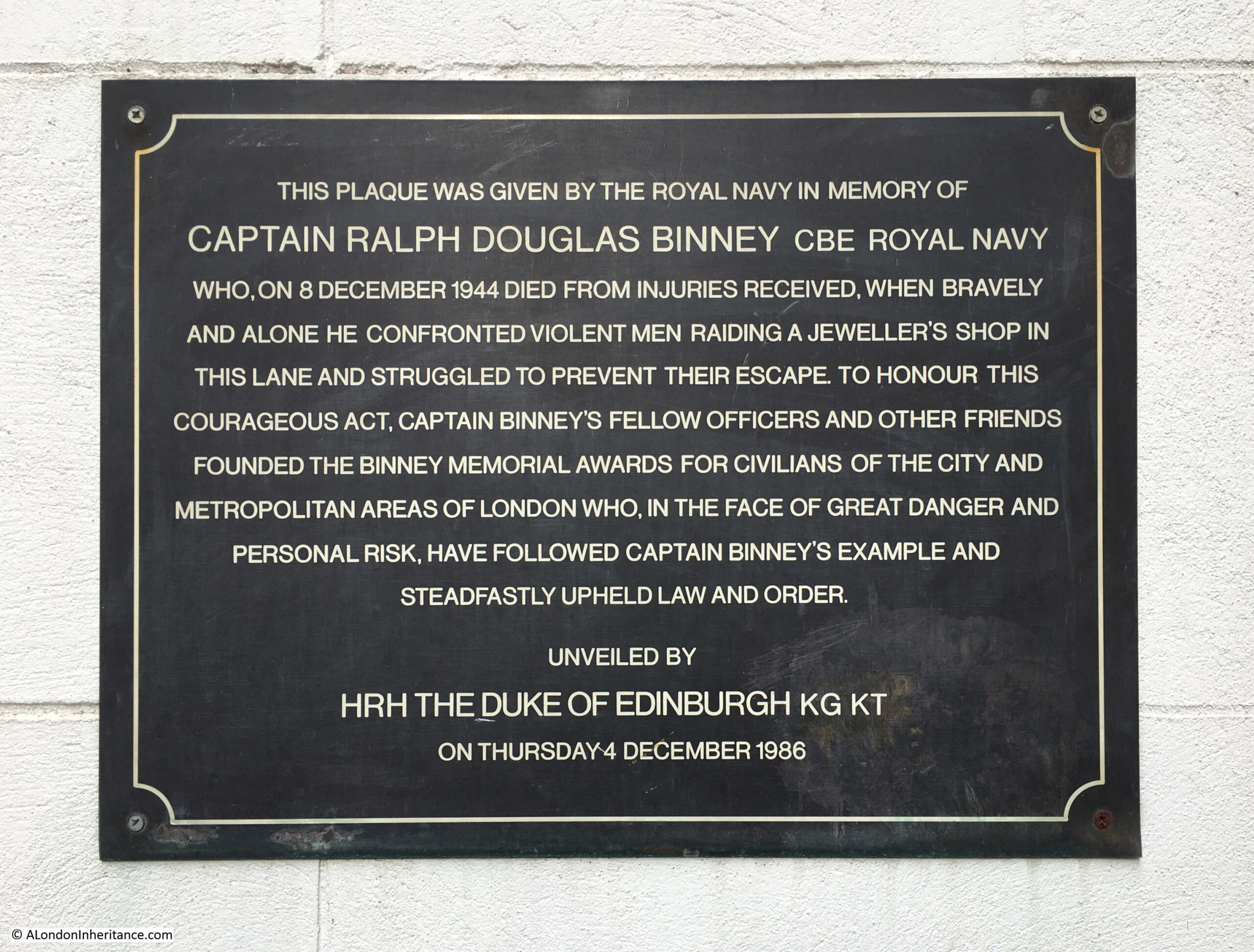

Captain Ralph Douglas Binney – Birchin Lane

The next plaque is in Birchin Lane, part of the network of narrow streets and alleys between Cornhill and Lombard Street. Roughly half way along the lane, close to the entrance to Bengal Court, there is a plaque on a side wall, to the right of the following photo:

The plaque was given by the Royal Navy in memory of Captain Ralph Douglas Binney who died on the 8th of December 1944 from injuries received, when bravely and alone he confronted violent men raiding a jeweller’s shop in the lane:

The event made the national newspapers, and the following is from the Daily Mirror on the 9th of December 1944:

“Captain Dragged To Death By Bandits’ Car: Horrified crowds saw an act of gangster callousness in the streets of London yesterday, as cold-blooded as anything known in the wild days of Chicago under prohibition.

They saw a 56 year old naval officer who had flung himself at a smash and grab bandits’ car dragged along to drop dying in the roadway half a mile further along.

They saw the car speed ruthlessly on as the officer, Captain Ralph Binney, caught in the chassis of the car, cried out for help. Captain Binney, chief staff officer to Admiral Naismith, leapt on to the running board of the car as it swept away at high speed from the shop of a jewellers in Birchin-lane, EC4.

The Captain called to the bandits to stop, but £3,500 of jewellery, looted from the shop window, and their own freedom was worth more than a human life to the robbers.

Driving on to King William-street, carrying the captain with them, the bandits disappeared towards London bridge.

Three hours later, in a quiet ward in Guy’s Hospital, the heroic captain murmured a dying farewell to his wife and his brother, Colonel Binney. His chief, Admiral Naismith hurried into the ward twenty minutes too late.

Last night the car was found abandoned in Tooley-street, SE. Police are anxious to contact anyone who, during the last few days, sold a new woodman’s axe, the weapon believed to have been used to smash the jewellers’ window.

Captain Binney had served thirty six years in the Navy. After six years in retirement he was put in charge of harbour defences at Gallipoli. On his return home in 1942 he was awarded the C.B.E.

Captain Binney leaves behind a widow and a daughter who is training as a nurse. His sub-lieutenant son was killed aboard H.M.S. Tyndale a year ago.”

There was a huge police hunt for those who had carried out the raid, and on the 12th of January, 1945 newspapers were reporting that “At Mansion House, London, today, Thomas James Jenkins (34), welder, of Rotherhithe, and Ronald Hedley, (26) labourer, were charged, with two men not in custody, with the murder of Capt. Binney, who, said counsel, was killed while doing his duty as a brave citizen.”

Ronald Hedley was convicted of the murder of Captain Binney and was sentenced to death, however this was later reprieved and he served 9 years in jail. Thomas Jenkins was convicted of manslaughter and was sentenced to 8 years in prison.

It appears that there were three others involved in the raid, but I cannot find any reference to their being identified, caught or sentenced.

Following Binney’s death, his naval colleagues formed a trust that would award a medal to a recipient who had shown bravery in the support of law and order in the areas controlled by the Metropolitan Police and the City of London Police.

The Binney award / medal appears to be an award that is still given, and is administered by the Association of Chief Police Officers, now covering the whole country, rather than the Metropolitan and City of London Police forces.

The next plaque is in Change Alley, which runs off from Birchin Lane:

Marine Society – Change Alley

Change Alley is a strange alley as there are multiple branches of the alley, including two separate branches between Cornhill and Lombard Street. In the core of this network of alleys is a blue plaque on the corner of a building:

The plaque records that it is on the site of the King’s Arms Tavern, where the first meeting of the Marine Society was held on the 25th of June, 1756:

1756 was the year of the start of the Seven Years’ War, which ran between 1756 and 1763, and could be called the first world war, as it involved England, Spain and France, Prussia, Austria, Russia and Sweden. With conflict taking place in North America, across the Oceans and in the colonies occupied by the countries involved.

England was at war with the French, and the Marine Society was formed to provide additional naval resources to support the conflict. A newspaper report from the 2nd of July, 1756 reports on the founding purpose of the society:

“We hear the Marine Society lately formed by some eminent Merchants of this City, intend to open with the following noble Scheme. They purpose to fit out a Number of fine sailing Ships of War, and to send them to invest the Island of Minorca quite round, in order to prevent the French from sending to their Army any Reinforcements of Supplies; and at the same time to distress their Commerce in the Mediterranean. We wish there may be Time for the Execution of such a public spirited project.”

The primary aim of the Marine Society was to recruit boys and young men for the Navy. They would be recruited from the poor, orphans, the homeless. They would be clothed and fed, then sent from London to join ships at one of the Navy dockyards.

The following year, in 1757, the Marine Society were sending recruits to the Navy. The following newspaper report is a typical example of mid-18th century journalism, and describes the process and ceremony when the recruits left London:

“Last Wednesday 75 friendless Boys and 40 stout young Men, all Volunteers, were completely clothed by the Marine Society to go on board the Fleet, and at One o’clock the same Day they were drawn up on Constitution Hill, in order to express their Gratitude to his Majesty with three Cheers for his late Royal Bounty.

His Majesty’s Coach went very slow all along the Bank, and a Smile expressive of paternal Delight overspread his Royal Countenance; from thence they marched to the Admiralty who expressed great Pleasure at the Sight; from thence the Boys went to Lord Blakeney’s Head in Bow-street, Covent Garden, to dine on Roast Beef and Plumb Pudding; and Members of the Marine Society to the Crown and Anchor Tavern to Dinner, which consisted of one Course made up of Dishes truly English, namely, Roast Beef, Hams and Haunches of Mutton; after Dinner his Majesty’s Health, the Prince of Wales’s, &c. were drank, attended by the proper Salutes of Cannon; in the Evening they marched with the Men and Boys at their Head, to the Theatre Royal in Drury-Lane, where the Comedy of the Suspicious Husband was performed for the Benefit of the Marine Society, to a most brilliant Audience.

The Men and Boys were on Thursday reviewed by the Marine Society, at the Royal Exchange, and marched off to Portsmouth.”

The term “friendless boys” refers to orphans. With the relatively high mortality rate among the poor of the City, it was not unusual for a child to loose both parents and be left on the streets. These children were one of the target recruiting areas for the Marine Society. How much they knew of what they were getting into, and whether they really were volunteers is questionable.

After the recruiting exercise covered in the above report, the King gave £1,000 “to be paid for the use of the Marine Society”.

The number of conflicts the country was involved in during the late 18th century required a continual supply of manpower for the Navy, and in 1790, the Marine Society “since the appearance of a Spanish war, have already clothed and fitted out for sea, 1672 men and boys, most of them poor wretches, a burden to the community”.

The last sentence again highlights the target area for recruits, and that they were considered a burden to the community. Their transfer to the Navy relieved that burden and put them into a role that society at the time considered worthwhile.

The Marine Society would evolve over the late 18th and 19th centuries. It was recognised that sending recruits to the Navy who had a degree of training was of more benefit, so the society started training, and in 1786 the Marine Society became the first organization in the world to have a dedicated training ship, moored in the Thames at Deptford, where recruits would be trained before being sent to the Navy and the Merchant fleet.

Training became a growing element of the Marine Society’s role. The Navy would grow their own recruiting and training operation, so the Marine Society expanded their brief to the Merchant Navy and seafarers in general.

Based in a rather nice red brick building in Lambeth, next to the railway into Waterloo, the Marine Society is still in operation today. In recent years it has merged with the Sea Cadets and is now a major training organisation for seafarers and the maritime community – all from that meeting in a tavern in Change Alley in 1756.

Change Alley is an interesting set of alleys to explore. Many of the buildings that face onto the alley are the backs of the buildings that face onto the main streets of the area, so they present a very different view. Of much cheaper construction, no ornamentation, and with exposed utilities, such as the following building with multiple pipes leading up to the sky:

Despite many of these buildings being hidden in the alley, some do have a degree of decoration relating to the company that occupied the building:

My next plaque was in the same alley:

Jonathan’s Coffee House – Change Alley

The following photo is in one of the legs of Change Alley, and to the right of the middle small tree, there is a blue plaque, down almost at ground level:

The plaque states that on the site stood Jonathan’s Coffee House between 1680 and 1778, the principal meeting place of the City’s stockbrokers:

Funds raised by the Crown and by Government had been in the form of arbitrary taxes and by the selling of the right to operate a monopoly, along with the raising of debts which were often not repaid.

As commercial activity expanded, and trade increased a more formal system was needed which ensured that the state could raise funds, and those lending these funds were assured that they would be repaid, with interest.

This led to the creation of “English Funds” which were basically the government debt which could be bought and sold. These funds would have a repayment date, and paid the owner of the funds interest. They therefore had a value.

Trading of these funds started in the Royal Exchange, and in 1698, many of those involved in the trading of these funds and securities started operating in Jonathan’s Coffee House in Change Alley. The move was down to laws that were enacted to limit the numbers of brokers and to more regulate the market, as so many people had been tempted into the market based on “false rumours and reports were propagated to raise or depreciate the value of stocks. Mines of wealth were promised, stratagems of every kind were rife; some made fortunes, others were ruined”.

Many of the roles and terminology in play at Jonathan’s Coffee House are still in use today, although many did disappear as recently as the 1980s with the deregulation of the Stock Market during the “Big Bang”.

An 1828 description of Jonathan’s Coffee House also describes the meaning of many of the terms associated with stocks and share trading:

“In Change-alley was formerly a rendezvous of dealing in the funds, and the term Alley is still a cant phrase for the Stock Exchange, and hence a petty speculator in the funds is styled ‘a dabbler in the alley’. A stock-broker is one who buys and sells stocks for another; his commission is one-eighth per cent. A stock-jobber is one who buys and sells on his own account, buys in when low and endeavours to sell out at a profit.

A gambler in the funds is one who speculates to buy or sell at a future time for a present price, who may lose or gain according as the prices then fall or rise; this being illegal, no action for recovery of loss can be maintained. The buyers are styled ‘bears’ as they endeavour to trample down the prices; the sellers are named bulls, for a like reason as they attempt to toss them as high as possible. One who becomes bankrupt is termed a lame duck, and he is said to ‘waddle out of the alley’. Those who have thus waddled are not again admitted to the Stock Exchange”.

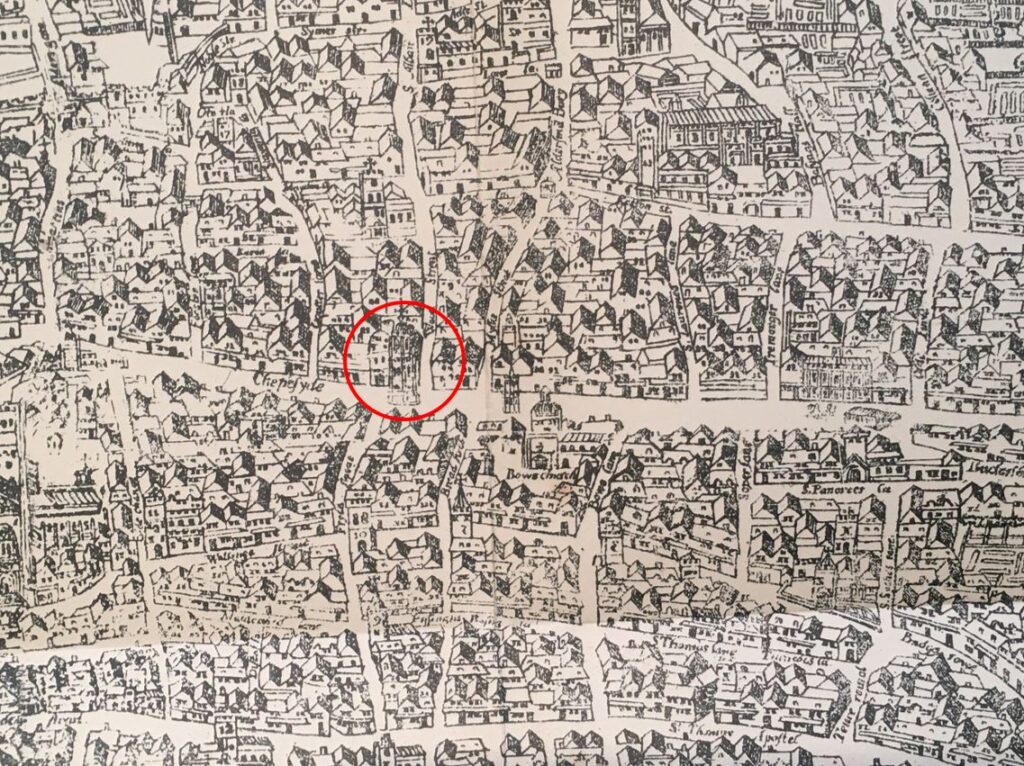

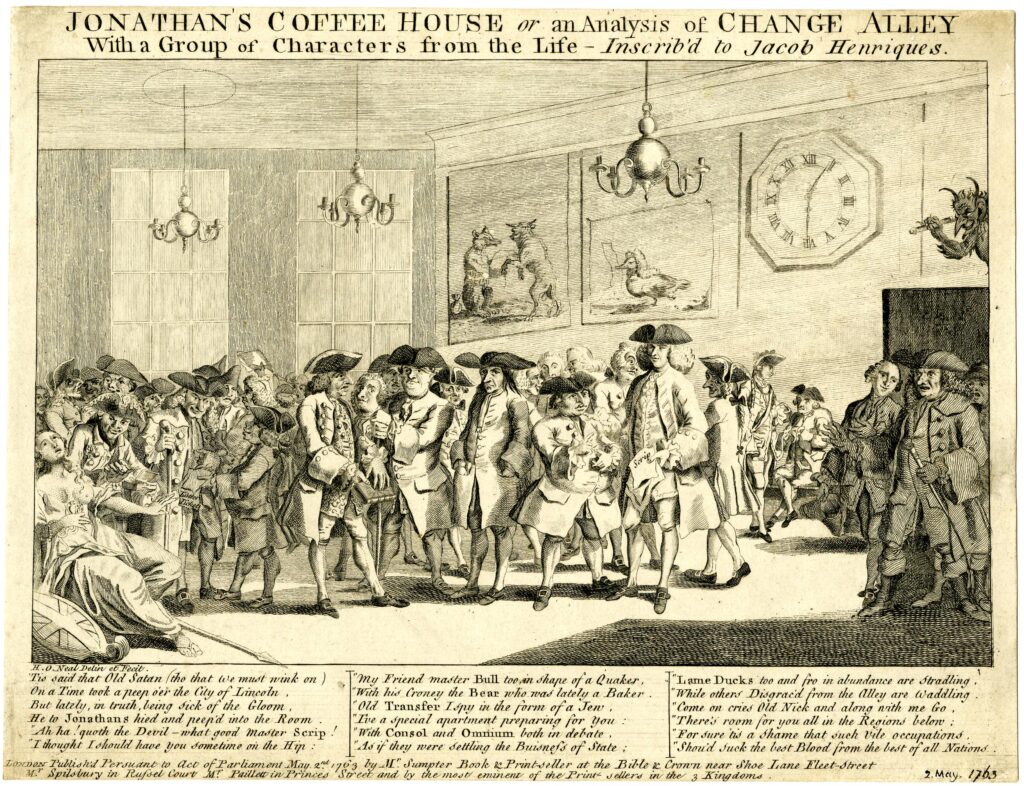

The following satirical print, dated the 2nd of May, 1763 shows Jonathan’s Coffee House, and the text below describes a visit by the Devil, who sees the characters in the coffee house, including the bull, the bear and the lame ducks, and old Nick cries that “there’s room for you all in the regions below”, and that “For sure ’tis a shame that such vile occupations, should suck the best blood from the best of all Nations” (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Jonathan’s Coffee House was destroyed in a fire that started on the 30th of March 1748 in Change Alley, in the premises of Mr Eldrige’s, a Peruke-maker (the long wigs worn by upper class men). Much of Change Alley, and some houses on Cornhill were destroyed, however Jonathan’s Coffee House was soon rebuilt, and trading continued.

Those engaged in trading at Jonathan’s Coffee House moved to a new location in Threadneedle Street in 1773, and papers on the 17th of July 1773 were reporting that at the new location: “Yesterday the brokers and others at New Jonathan’s came to a resolution, that instead of it being called New Jonathan’s, it should be named The Stock Exchange, which is to be wrote over the door. The brokers then collected sixpence each, and christened the House with punch.”

The Stock Exchange as it was now called began trading on more formal lines, and traders had to pay a fee to enter the trading room.

The Stock Exchange would continue trading within a physical place until the 1980s, when the deregulation of London’s financial markets resulted in the transition to screen based trading. The Stock Exchange moved from their Threadneedle Street location to offices in Paternoster Square in 2004 as a trading location was not needed, only offices for the administration, regulation and management of the Stock Exchange.

Following the change of debt being raised by the country, rather than the Crown imposing taxes or borrowing money, the national debt has always been a cause for concern.

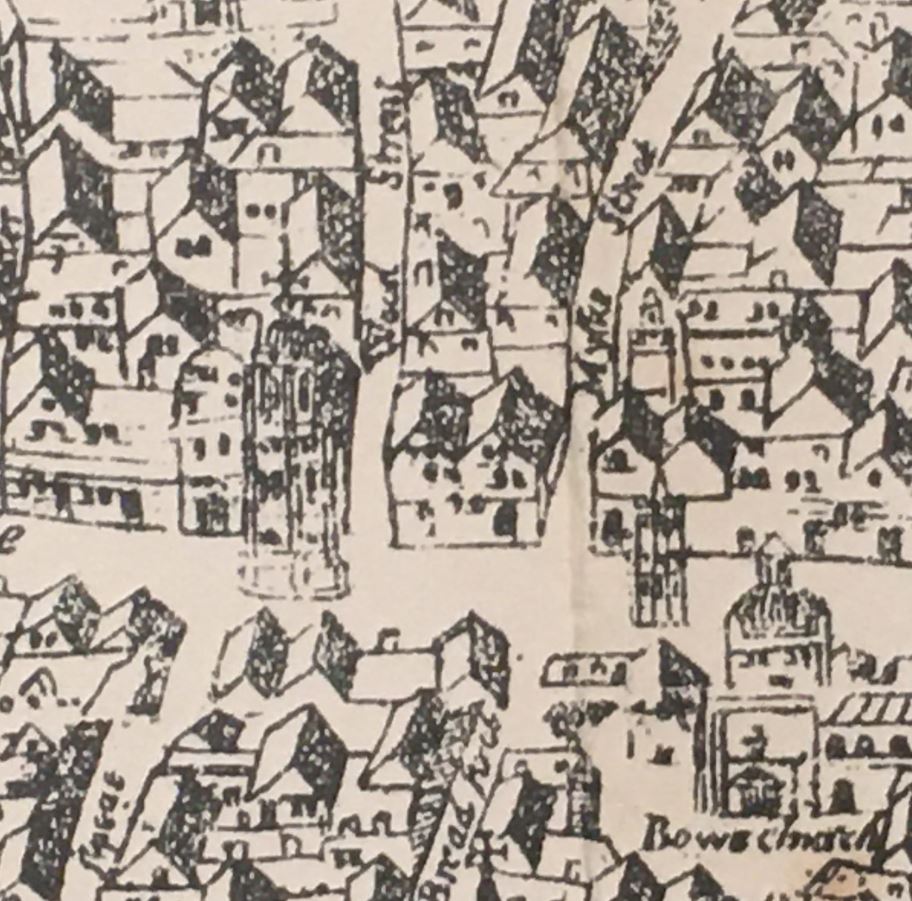

The print below is a satirical print published in 1785 showing the Stock Exchange supporting the national debt in 1782, or what the print called the “English Balloon” (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

In 1783, the National Debt stood at around £250 million. It had risen throughout the 18th century due to the many wars that the country was involved with. and which required considerable funding. Pitt the Younger who became Prime Minister in December 1783 put in place a number of changes to both clamp down on tax evasion (such as smuggling), and increasing taxes which resulted in the debt coming under control and confidence in the Pound being restored.

By comparison, the Office for National Statistics reports that the UK debt was £2,436.7 billion at the end of Quarter 2 (Apr to June) 2022. Taxes are increasing and there was recently a brief loss of confidence in the Pound – something’s never really change. The “English Balloon” just gets much larger.

My final location is in Lombard Street, to the south of Change Alley, however my last comment on the alley is the origin of the name. It was originally called Exchange Alley as it was opposite the Royal Exchange. The name simply became abbreviated to Change Alley. Now leaving the alley to the south to find:

Lloyd’s Coffee House – Lombard Street

To the right of the main entrance to Sainsbury’s in the following photo is a blue plaque:

Marking the site of Lloyd’s Coffee House:

Very much like Jonathan’s Coffee House, Lloyd’s Coffee House was the original site for a City institution that is still running today.

Lloyd’s Coffee House was opened by an Edward Lloyd in February 1688. Initially in Tower Street, the Coffee House moved to the Lombard Street location indicated by the plaque in 1691.

Lloyd’s Coffee House became a meeting place for those involved in shipping and marine insurance.

The coffee house started publishing its own newspaper using the information gathered from customers, and the paper became an essential resource for those working in shipping related industries of the City.

An article / advertisement published on the 12th of June, 1758 explained why the paper had so much early information:

“This day is published number 140 of Lloyd’s Evening Post and British Chronicle. A paper of Military, Naval, Commercial and Literary Intelligence published every Monday, Wednesday and Friday evening at Seven O’clock.

Lloyd’s Coffee House is known to be the centre of intelligence, from the most considerable trading parts of the world, and accounts of naval transactions are frequently received there even before they arrive at the First Offices of State. Many articles of intelligence have therefore appeared in this paper, the authenticity of which has been questioned by news writers in the common posts, who, unable to fathom how they were attainable at first have, after exploding them, adopted and inferred them in their Papers as new, many days after they appeared in this.

It is no wonder therefore that this paper has met with uncommon opposition, the most notorious falsehoods have been propagated to prejudice it, its connection with Lloyd’s Coffee House has been publicly denied, and the facts inferred in it have been efficiently discredited. Notwithstanding which the paper thrives. Truth, which will always manifest itself, has dispersed the clouds of falsehood, and the merit of the paper has rendered all detraction and opposition ineffectual.

Advertisements are taken in at Lloyd’s Coffee House in Lombard Street.”

I love that the colourful language of the article, defending its position as an early source of news, ends with a simple statement about where advertisements should be sent.

Edward Lloyd died on the 15th of February 1713, and his son-in-law William Newton took over. Newton had married Lloyd’s daughter Handy, who died in 1720.

After 1763, the reputation of the coffee house started to decline. It became a place of gambling and also stock jobbing (as took place at Jonathan’s Coffee House), and a New Lloyd’s Coffee House opened at 5 Pope’s Head Alley in 1769, although the Lombard Street coffee house continued in business, still a meeting place for those in the shipping and maritime insurance trades.

The Society for the Registry of Shipping was founded at Lloyd’s Coffee House in 1760, and in 1786 the society moved to new premised at number 4 Sun Court, Cornhill.

So from Lloyd’s Coffee House, two City institutions evolved:

- what would become the Lloyds of London Insurance market were the activities that moved from Lloyd’s Coffee House to 5 Pope’s Head Alley and;

- what would become Lloyd’s Register which is now in Fenchurch Street were the activities that moved from Lloyd’s Coffee House to 4 Sun Court.

Five very different plaques which highlight the varied history of the City of London, and which have had significant influence on the city we see today.