In addition to photos of London, my father took lots of photos of the rest of the country whilst cycling and staying at Youth Hostels (a very popular post war pursuit) and during National Service. As well as tracking down all the locations of the London photos, I have a side project to track down this geographically wider set of photos. I have already featured a number of these locations in previous posts and this week I am visiting Chepstow and the River Wye.

These photos were taken in 1947 whilst my father was based with the army near Chepstow as part of his National Service. The post will be in two parts, today covering the town of Chepstow and the River Wye. A mid-week post will visit Chepstow Castle. Construction of the castle started in 1067 which makes Chepstow one of the earliest Norman castles in the country. I will be back in London next Sunday.

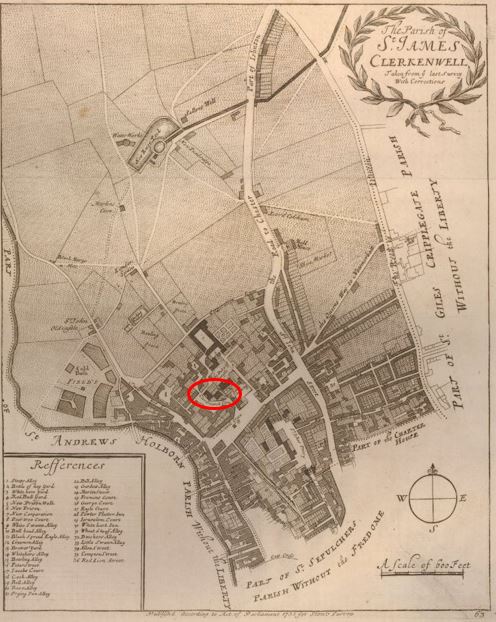

The River Wye runs up from the River Severn and here forms the boundary between England and Wales. Chepstow is located in one of the many loops of the River Wye, just on the Welsh side of the river, not far from the River Severn.

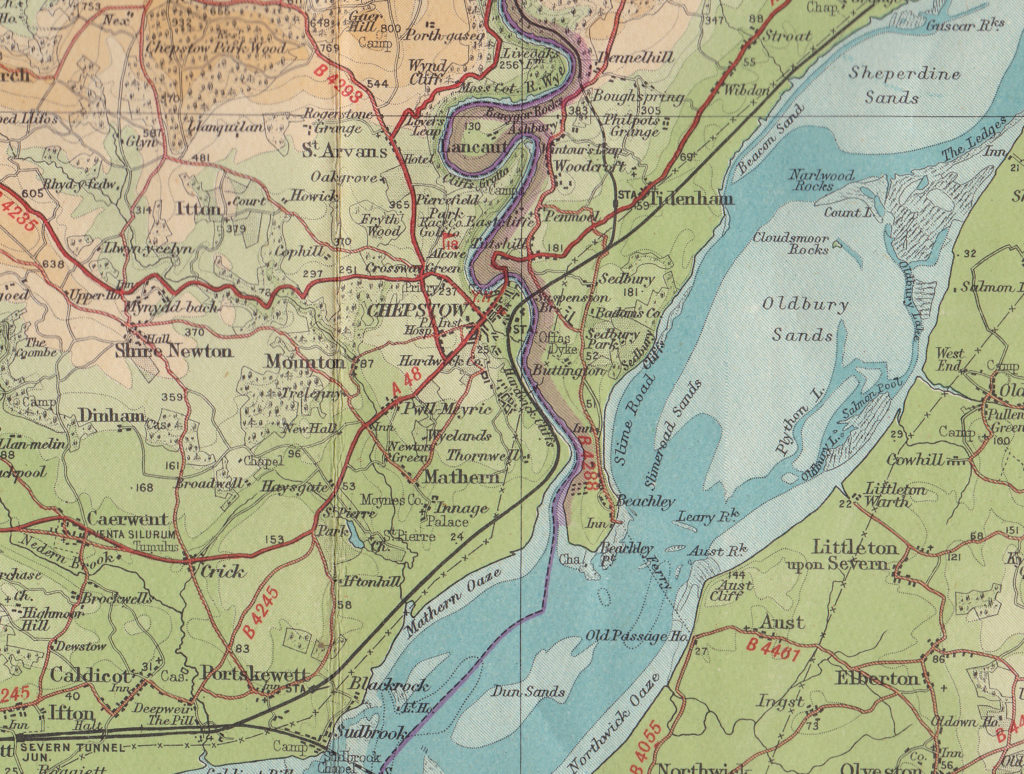

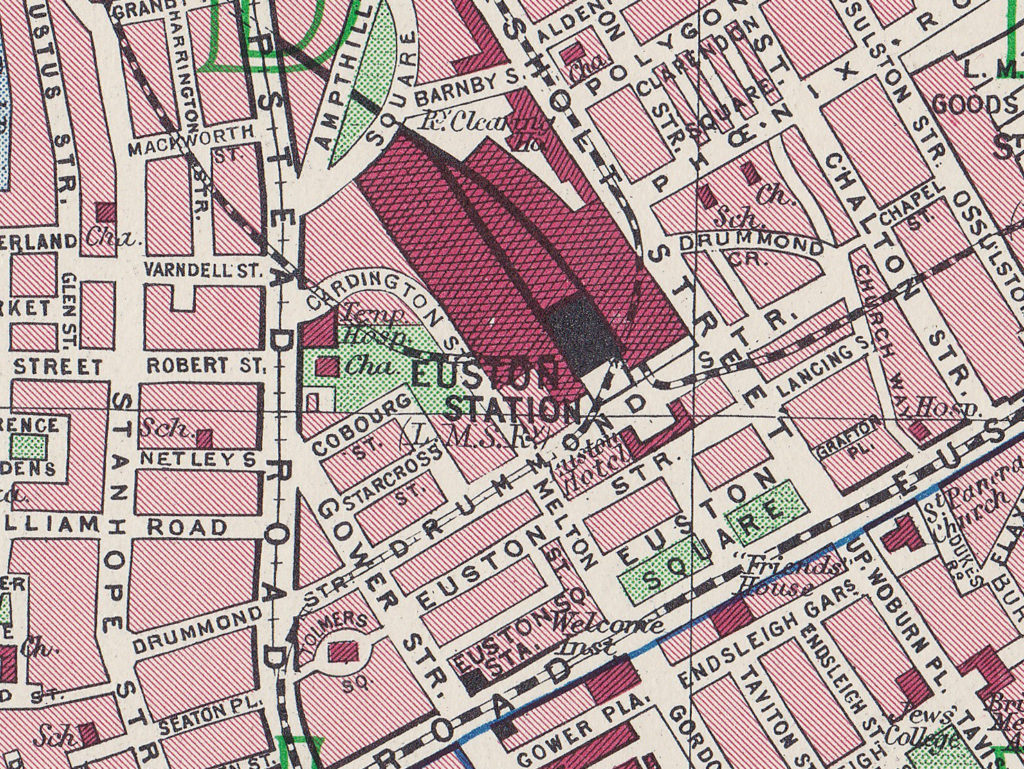

The following extract from a 1930s edition of Bartholomew’s Revised Half Inch Contour Maps shows the location of Chepstow. These are wonderful maps, their use of colour to show the height of the land, the typeface used for the lettering and the symbols used for landscape features produced maps that are lovely to look at as well as highly functional.

The River Wye between Goodrich, Monmouth and Chepstow runs through several sections of limestone, with deep valleys, large meanders and densely forested cliffs. Meanders are usually associated with a sluggish river, but this is not so with the Wye. It is a fast running river and also has one of the highest tidal ranges in the world with a range of up to 44 feet (13.4m) at the bridge in Chepstow. Large volumes of water are therefore moved up and down the river each day.

Despite the large tidal range, Chepstow was once a thriving port. The town’s location within the Welsh Marches meant that imports and exports were free from duties to the Crown, providing that the ships did not call at Bristol.

Such was the success of the port of Chepstow that in 1791 there were 31 ships belonging to the town of 2,495 tonnage which grew to 75 ships with a tonnage of 5,782 in 1824.

Trade from Cheptow was with the rest of the UK as well as the Continent and ships from Chepstow carried spirits, wines, wheat, barley, flour, cider, iron, millstones and timber for the navy from the forests that lined the Wye Valley. The level of trade justified a Customs House at Chepstow which was in operation until the mid 1850s. Goods were also transferred from sea going ships at Chepstow onto lighters which would transfer goods further up the River Wye, to towns such as Monmouth, Hereford and Hay on Wye.

The port went into decline after the 1850s, probably due to the arrival of the railway at Chepstow in the same decade. Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s railway bridge across the Wye at Chepstow was a remarkable engineering achievement and whilst a new support structure was put in place in 1962, Brunel’s original cast iron pillars still support the bridge.

Time to take a walk to explore Chepstow and the River Wye. According to my father’s notes all the Chepstow photos were taken over two weekends, the 5th and 6th and the 12th and 13th of July 1947, so I assume these were periods of leave. In the collection there are also many photos of army life at Chepstow, including one of a troop of 18 and 19 year National Service recruits leaving “for a p*** up”, so I am not sure if the inhabitants of a quiet Welsh market town appreciated having the army so close. My visit to Chepstow was on Saturday the 8th July so as close as I could get to being exactly 70 years between the two sets of photos.

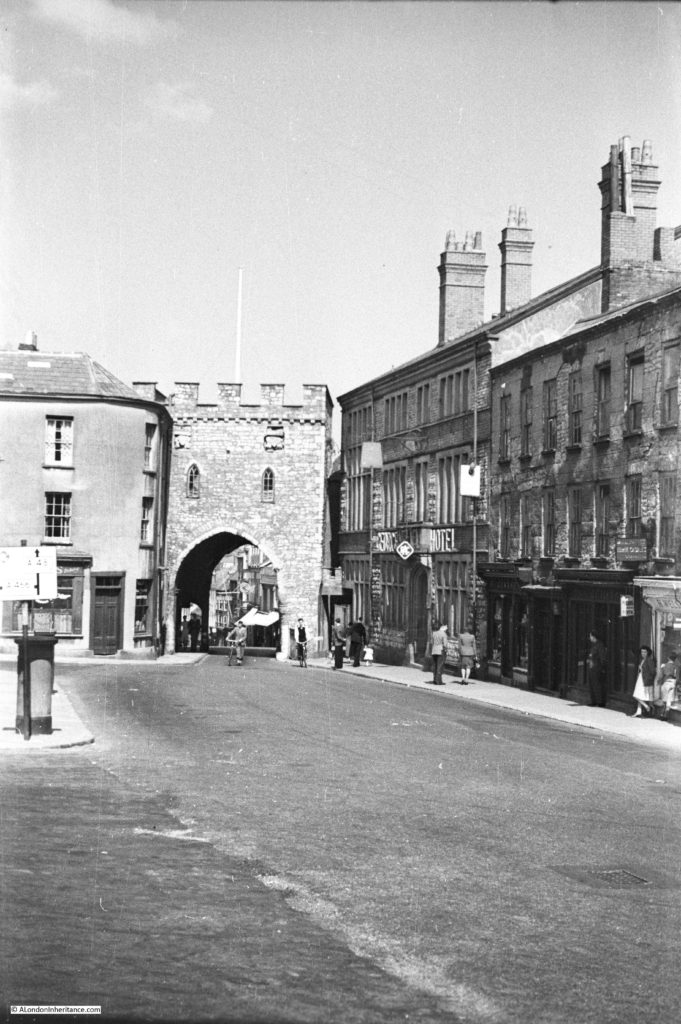

I will start just outside the original town, at the entrance to the Town Gate, originally the only landward entry to Chepstow in the walls that surrounded the town and port.

The original town gate was built in the 13th century at the same time as the walls. The gate in place today dates from the 16th century with the usual repairs, part rebuilds and modifications that would be expected for a building in such a prominent position in over 400 years.

On the right of the town gate is the George Hotel. An Inn has been here since the early 17th century however the current building dares from 1899.

The same view today, 70 years later. Mainly cosmetic changes to the buildings. The increase in road traffic is such that traffic lights now control traffic through the town gate.

Walking through the Town Gate takes us into the High Street. This is the view looking up the High Street back towards the gate.

And looking down the High Street from the same position. These two photos show the slope of the land as it descends down towards the River Wye.

Thankfully Chepstow retains the feel of a local town with individual businesses rather than being overrun with national chains, although one national coffee chain has established a prominent position at the bottom of the High Street.

Along the High Street, I found a connection with London, although a rather derogatory reference:

The text is from a poem by the Rev. E. Davies:

Unlike the flabby fish in London sold,

A Chepstow Salmon’s worth his weight in gold,

Crimps up delightful to the taste and sight,

In flakes alternate of fine red and white,

Few other rivers such fine Salmon feed,

Nor Taff, nor Tay, nor Tyne, nor Trent, nor Tweed.

The earliest references to this poem I have found are from the early 19th Century so this was written at a time when salmon were relatively abundant in the River Wye at Chepstow. Salmon numbers have fluctuated considerably over the centuries, periods of over fishing and poaching as well as environmental factors have contributed to reductions in numbers however salmon seem to recover well and the 1960s and 70s were record decades with salmon weighing in excess of 30lbs and measuring over 4ft long being caught and over 6,000 being caught each year in the late 1980s.

Salmon numbers plummeted dramatically soon after so by 2002 only 357 salmon were caught. Numbers are gradually recovering and in 2016 there was a spring catch of over 500 as salmon returned to the river in numbers not seen for 20 years.

I did not get a chance to try a Chepstow salmon so cannot compare with the flabby fish in London.

From the High Street, I walked into Middle Street and immediately along the pedestrianised St. Mary Street.

This is the view looking up St. Mary Street. The Chepstow Bookshop is on the left of this street – a brilliant independent bookshop where I bought a couple of books on the history of the area.

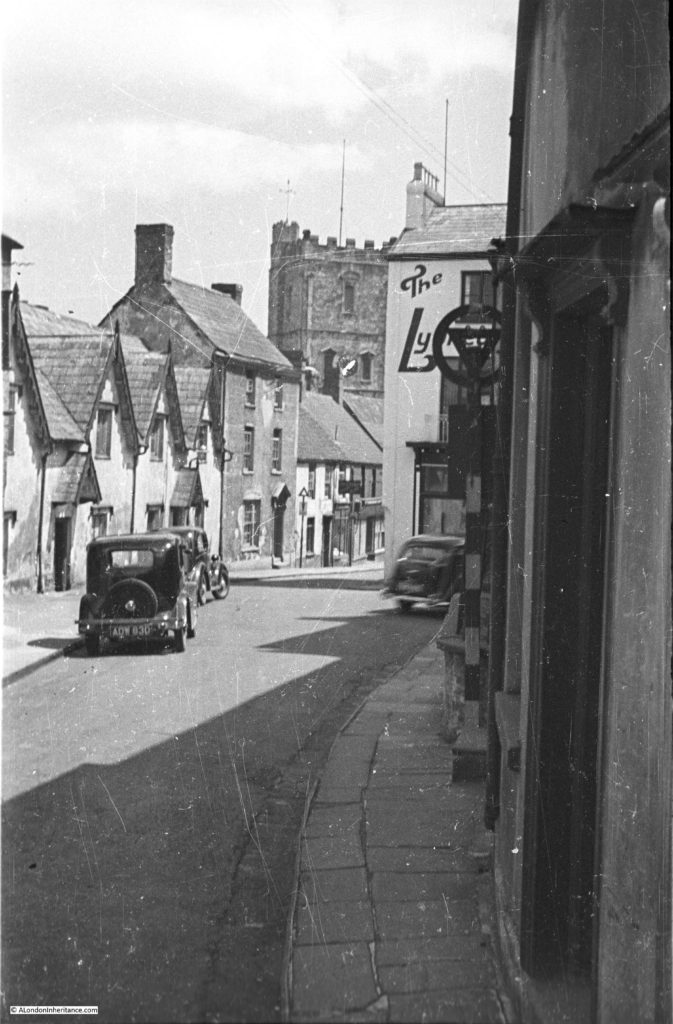

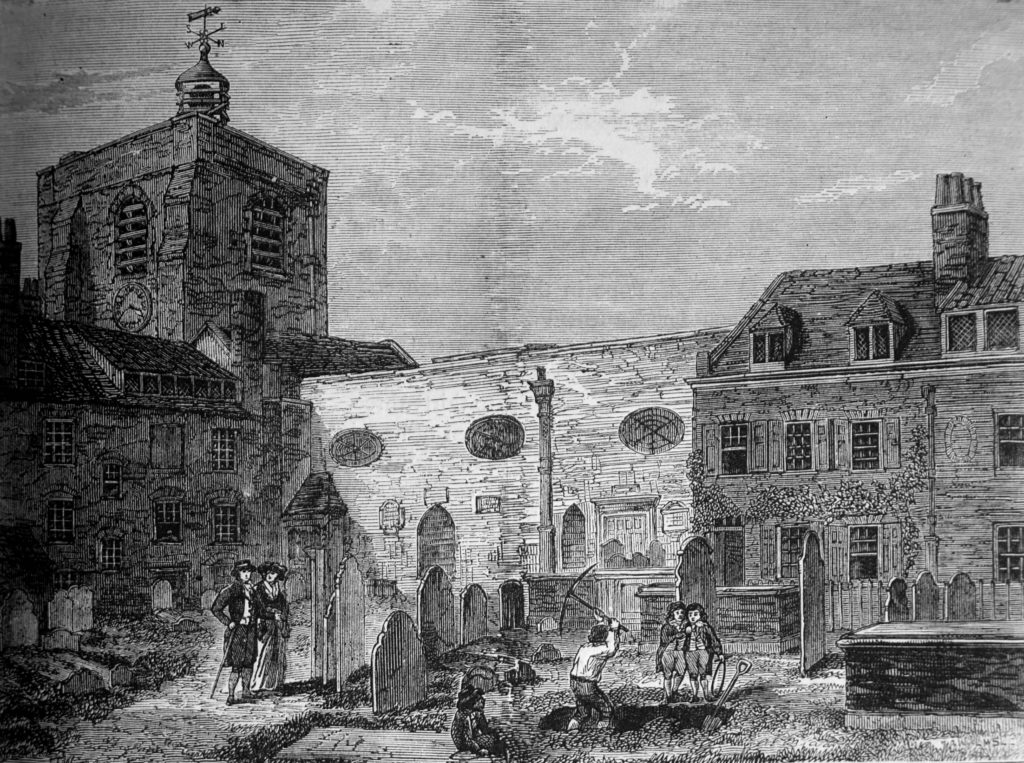

At the end of St. Mary Street is Upper Church Street and this was the view in 1947:

And the same view in 2017 which stupidly I took in landscape rather than the portrait format of the original.

Again the scene is much the same with only cosmetic differences. There is however one remarkable difference between the two. All my photography of street scenes and buildings today are generally plagued by cars. Roadside parking and street traffic generally obstructing the view of a building or scene, however in the above pair of photos there are three cars in 1947 and nothing in 2017. Traffic in Chepstow is much lighter than London and I was lucky that there was no parking in the marked bay in front of me, but it did seem strange not to be trying to take a photo in between parked and passing traffic.

Staying in the same position as the above two photos, but turning to look in the opposite direction is this large old building in Bridge Street at the end of Upper Church Street.

These are the Powis Alsmhouses. The plaque above the door states that the almshouses were built following an endowment in 1716 from Thomas Powis, a Vintner from Enfield in Middlesex for six poor men and six poor women of the town and parish. His connection with Chepstow is that he was born in the town. The cellars underneath the almshouses were used by wine merchants during the 18th century.

The almshouses are now Grade II listed and the following photo shows the full building, which again is little changed from 1947.

Above the plague there is a sundial projecting from the edge of the roof. This was also in the 1947 photo.

Bridge Street, as the name suggests is the road that leads down to the original bridge over the River Wye, linking Chepstow to England. One side of the street is lined by 3 storey houses. This is Castle Terrace and consists of an unbroken row of 14 Georgian houses built between 1805 and 1822. The rear of the houses look out onto the castle. They are also Grade II listed.

At the end of Bridge Street is the bridge over the River Wye. This was the view in 1947 a short distance on the bridge looking back towards Chepstow.

70 years later the view is much the same.

The building at the end of the bridge surrounded by scaffolding was the Bridge Inn, a Grade II listed pub, however the pub has now closed and the building is being converted into a cafe, shop and apartments. Just one of the twenty one pubs that are closing each week according to a Campaign for Real Ale report.

The bridge provides a very dramatic view of the River Wye and Chepstow Castle. This is the 1947 view with a high tide showing the full width of the river.

Similar view in 2017 – rather more ornate lights have replaced the 1947 versions.

The tidal range of the River Wye at Chepstow is one of the largest in the world. The lowest astronomical tide is 1.2m and the highest is 14.6m giving a maximum tidal range of 13.4m (44 ft). The highest tidal range of 16.2m is at the Bay of Fundy in eastern Canada, 15m at Ungava Bay in north eastern Canada, followed by 14.7m across the Severn Estuary, then Chepstow at 14.6m.

The following photo was taken as the tide was receding – low tide had not yet been reached. Tide height can be seen by the height of the mud banks and also by the tide line on the cliffs in the distance.

There is a much later road bridge carrying the A48 into Chepstow, however this is the original road bridge.

There has been a bridge on the site since the 13th century, the first built of wood and with a central stone arch it was subject to frequent damage requiring a ferry to provide transport across the river until it was repaired. There was also an earlier Roman bridge further upstream.

The current bridge was built between 1815 and 1816 and is the largest remaining iron arch bridge built prior to 1830. The original Ironbridge in Shropshire is about 35 years older but is a shorter bridge than the one at Chepstow.

The bridge was designed and built by John Urpeth Rastrick – an engineer who has been rather overshadowed by the likes of Brunel and Thomas Telford.

Born in 1780 in Morpeth, Northumberland, Rastrick built steam engines, including the first engine to be run in the USA. He was the chairman of the judging panel for the Rainhill Trials in 1829 where 5 engines competed along a mile of track at Rainhill. Stephenson’s Rocket was the only engine to complete the trials. He was also the engineer for the extension of the London to Brighton railway from Croydon to Brighton.

If you look back at the map at the top of the post, the bridge carried the A48 across the River Wye and was the only road bridge to cross this section of the river. Also, if you follow the River Wye down to where it meets the River Severn you can see there is a ferry at Beachley. This was long before the Severn road crossings were built and the only route across was via the ferry or a long detour via Gloucester.

The bridge has a very elegant design and looks remarkable during a very high tide when the water fully covers the concrete piers and the white arches appear to be floating on the water.

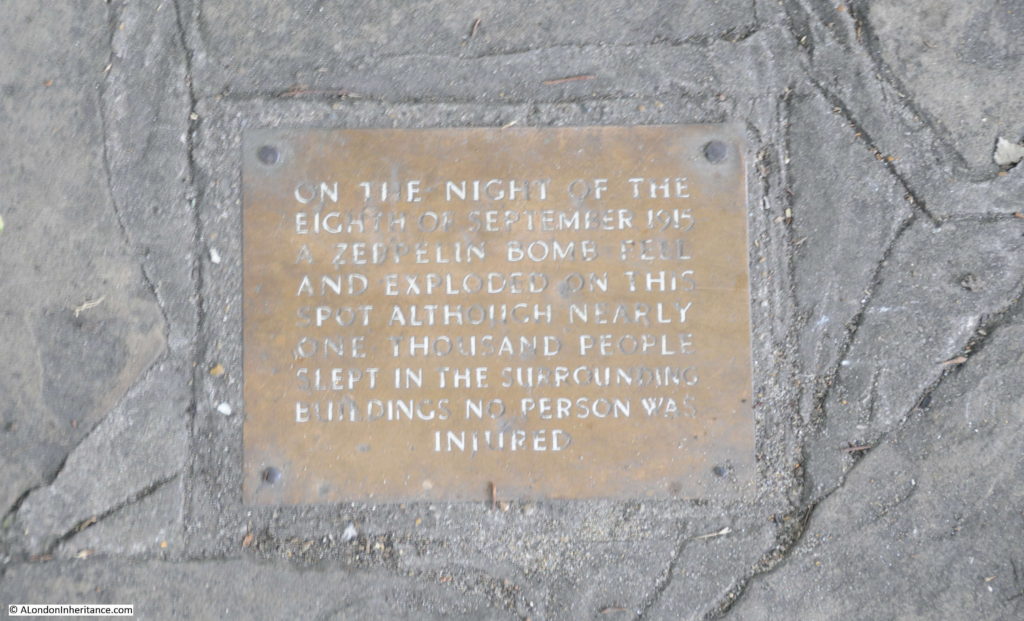

As well as the high tide, the Wye has been known to flood. In the photo below there is a plaque at the bottom of the white pillar at the end of the railings. The plaque marks the high tide level on the 17th October 1883.

The River Wye is home to a growing population of salmon, and there have been very occasional sightings of seals who have come up from the River Severn to hunt fish. Remarkably on the day of my visit there was a seal hunting for fish in the muddy water slightly downstream of the bridge.

A short distance from the bridge, there is a small wine bar / restaurant along the banks of the Wye. A July day with a beer and some food sitting outside along the banks of the River Wye was hard to beat.

Directly opposite are these limestone cliffs. There is a large, square hole in the cliffs. This opens out onto a much larger chamber. There are a number of possible origins and use of the chamber, one of the most credible uses was to unload and provide a temporary storage place for goods that could not be unloaded from ships at the shallower wharves across the river.

If you look just below and to the right of the hole is a Union Jack. This was originally painted in 1935 for the Silver Jubilee of King George V. The flag has been repainted a number of times since.

The tide mark for a high tide is very visible in the above photo and in January 2014 heavy rains and flooding caused the River Wye to reach above the flag.

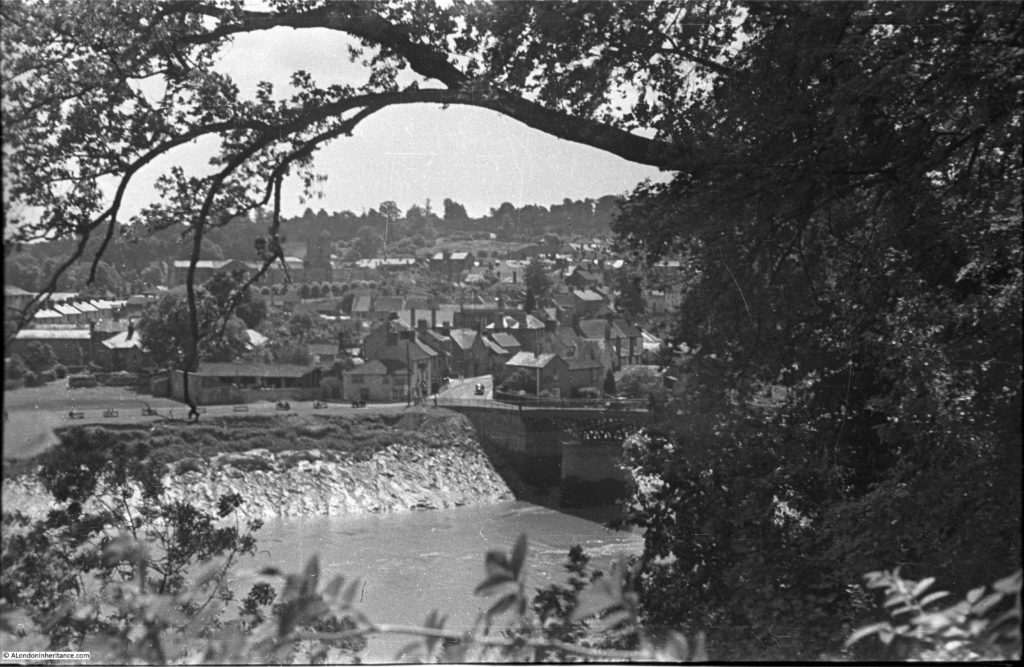

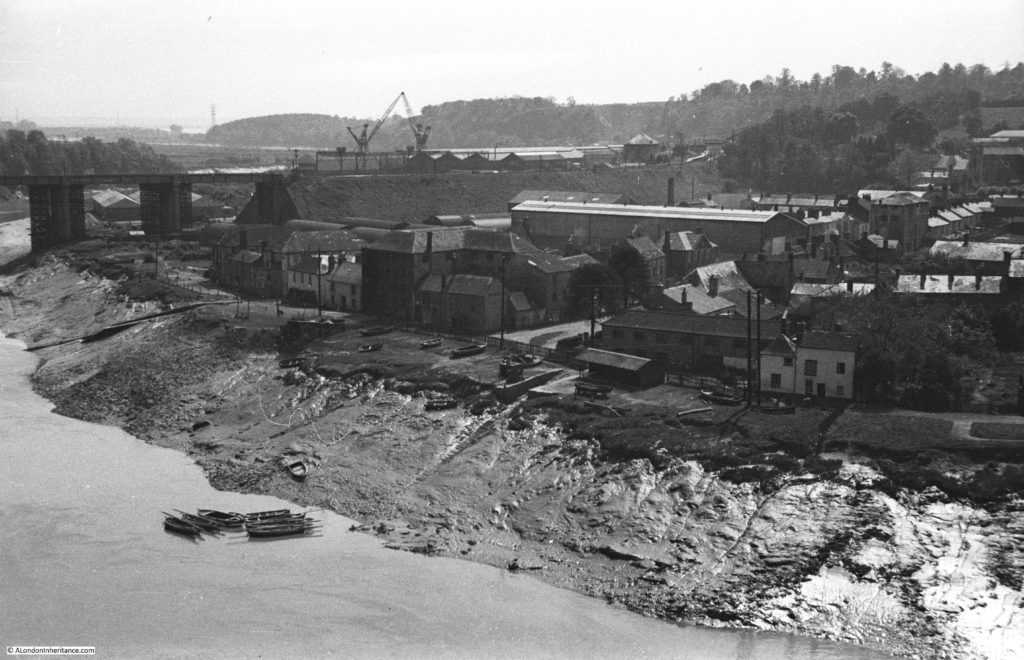

My father took the following photo from the top of the cliffs shown in the above photo, looking back onto Chepstow and the River Wye. I tried to get up to the same spot, however housing seems to have been built along the cliff and I could not find the same view point, although I was by then short of time, so an excuse for another visit.

There are rows of benches along the river’s edge in the above photo. Then as today, this is a lovely place to sit on a summer’s day and watch the rise and fall of the tides.

I assume the following photo was from around the same spot as the above. This is looking downstream and the railway bridge across the river can be seen on the left. The white painted building towards the right of the photo facing the river is now the Riverside Wine Bar. The photo again gives a good view of the tidal range at Chepstow.

Chepstow and the River Wye is a wonderful place to visit and I was really pleased that tracking down the locations of the old photos provided the motivation to make the journey. There was much more to see – I will cover the castle in my next post, however the town also has a museum (which I did not get time to visit), there are long walks along the River Wye and Chepstow has some excellent pubs and restaurants (one of which I did get the time to visit).

From London, Chepstow is roughly a three hour train journey, or by car, straight down the M4 then turn right after crossing the River Severn – it is well worth the journey.