St Mary Woolnoth is an unusual church. A short distance from the Bank, the church can be found at the junction of Lombard Street and King William Street. St Mary Woolnoth has one of the more unusual towers of the City churches, a Hawksmoor church, built after post Great Fire repairs to the medieval church failed, a church that survived the blitz, but 50 years earlier had almost been lost to the City and South London Railway.

The view of St Mary Woolnoth from the Bank junction.

The church occupies a small space, surrounded by City offices and from this perspective, the unusual tower is clearly viewed.

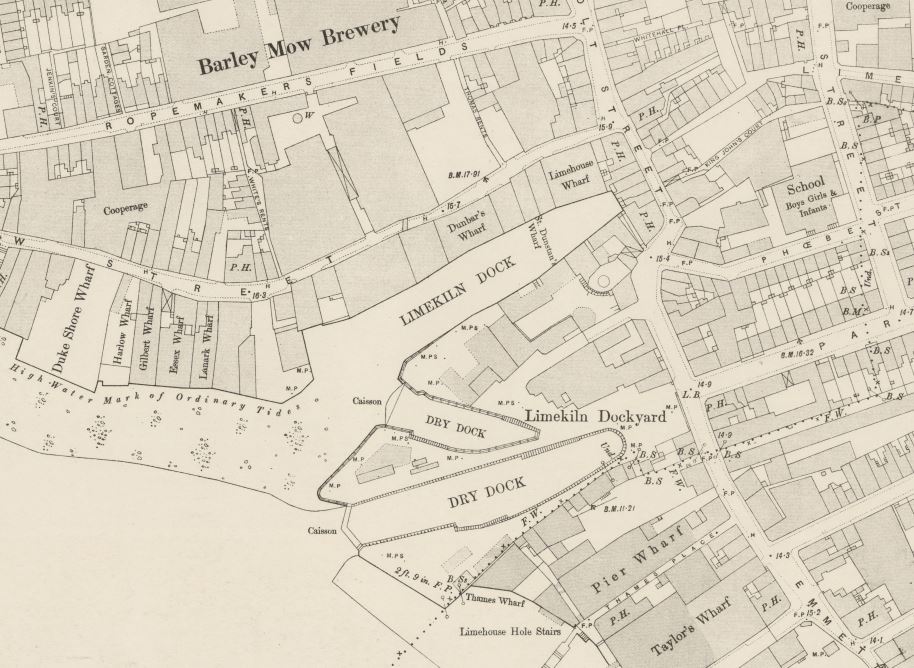

The current church was built between 1716 and 1727 by Nicholas Hawksmoor. The previous church had partly survived the Great Fire of 1666, but needed considerable repair. This work was carried out from 1670, but there were obviously problems repairing a medieval church which led to the decision for Hawksmoor’s replacement church in the early decades of the 18th century. The new church was part of the plan for 50 new churches, funded by a tax on coal.

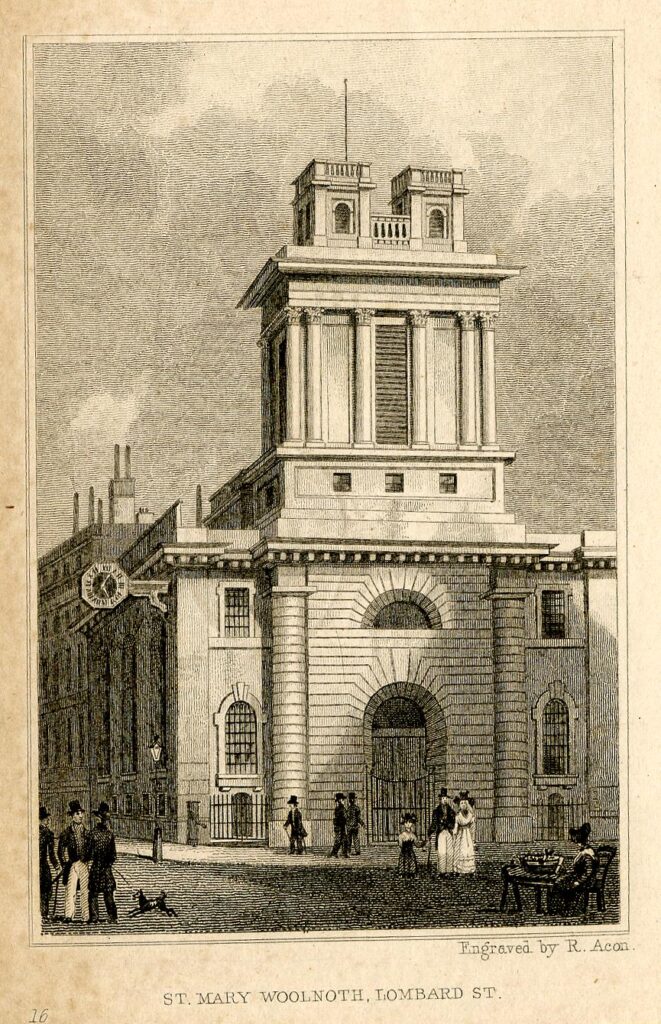

The tower is interesting. From the front it is substantial and broad, but look from the side and the tower is narrow. Four columns give the impression of two separate towers, this view being reinforced by the two small turrets rising at the top. The turrets are small versions of the square towers that would normally be expected on a City church.

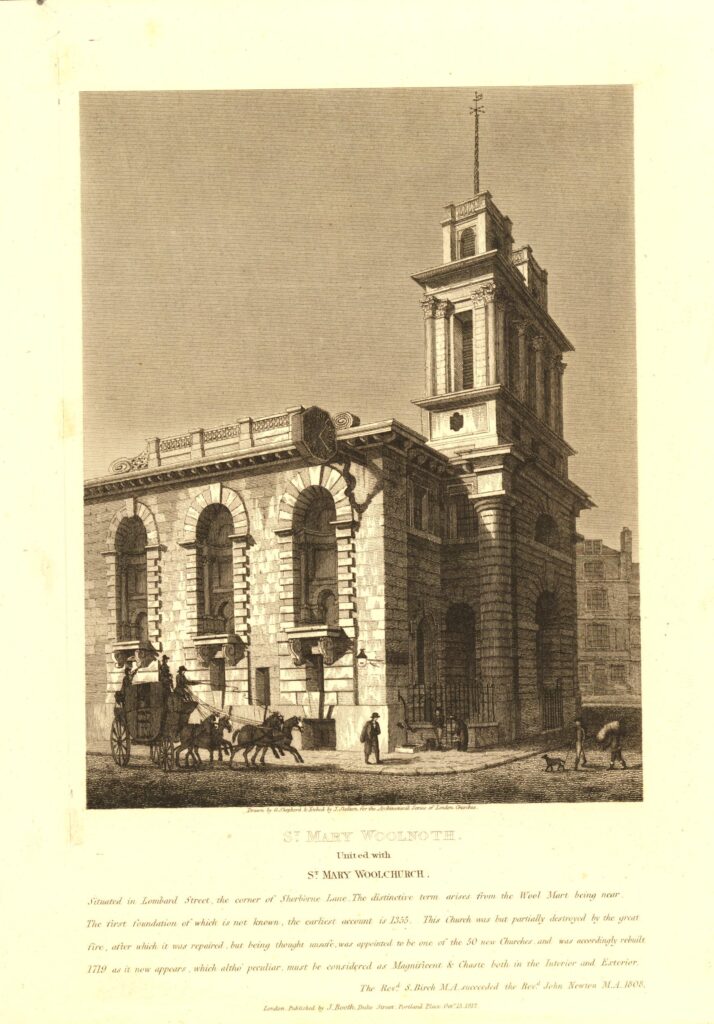

This print from 1838 shows St Mary Woolnoth when the tower of the church was still higher than the surrounding buildings. Note the clock on the left wall of the church, over hanging the street. The clock is still a feature of the church today.

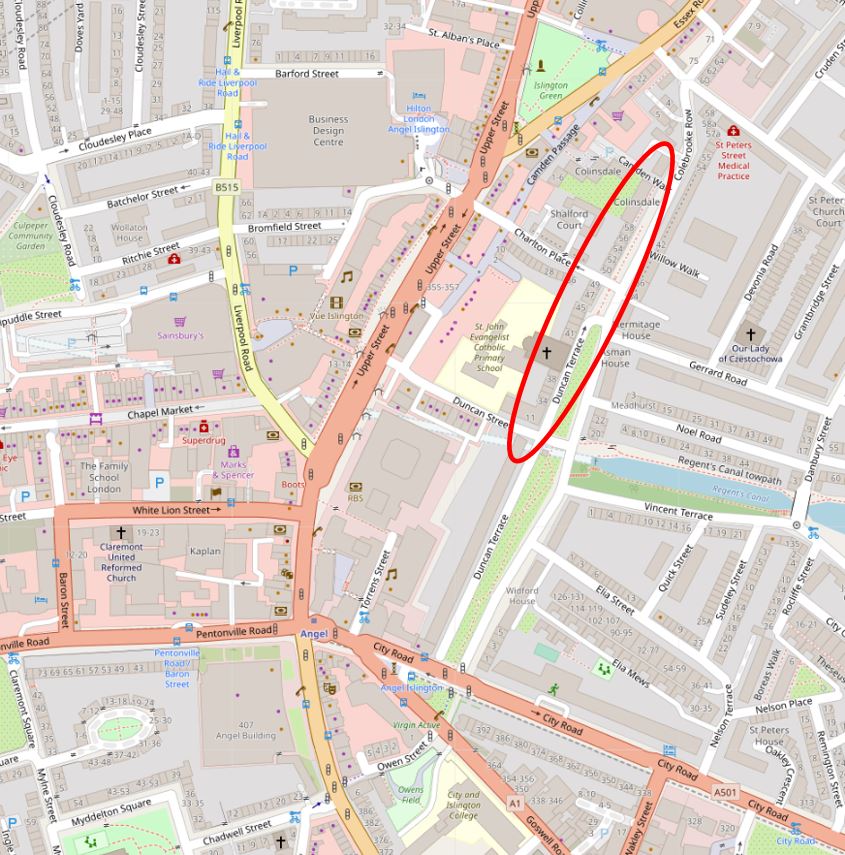

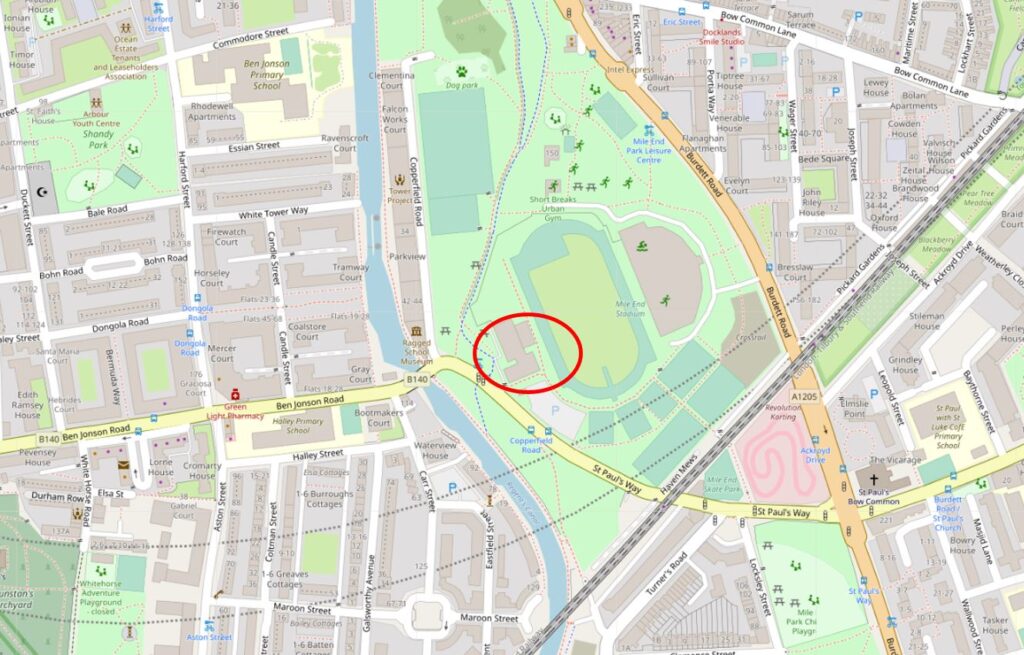

As well as the tower, another feature of the church is one that almost led to its destruction. If you look along the King William Street side of the church, there is an ornate wall projecting out from the corner of the church, today being the location for a Starbucks. In the far arch of the wall can be found the entrance to a lift.

The City and South London Railway had opened in 1890. The railway had originally been planned to run from King William Street to the Elephant and Castle, however extensions were being quickly implemented and the line would eventually become the eastern branch of the Northern Line.

The City and South London Railway required space around the Bank in what was already a very congested area. The late 19th century was a time when a number of City churches were demolished as the population of the City had declined and there was no longer a sufficient congregation for what was still a number of churches that suited the Medieval City rather than the Victorian City.

Although proposals for the demolition of the church were put forward, a compromise was agreed, as detailed in the following report from the Standard on Friday November 23rd 1900:

“In 1893 the Railway Company obtained an Act for making a railway, and under that Act they scheduled the site of the church. Owing to the lack of means there was no opposition to the Act on the part of the churchwardens, and the only portion of the Act which affected the church was the clause relating to the removal of human remains which might be disturbed.

Nothing was done till 1896, when the Company obtained an Act to extend the period for the construction of the line. Opposition was then raised by the present Claimants and the Bill was opposed in both Houses, though in the protection of public monuments. the result was that in the Act a clause was inserted that the Company could not purchase any part of the church, but only portions of the land adjacent and under the church, and the clause provided that the arbitrator, in considering the compensation, should take into account the additional cost to the Company of this change to their plans.

in February 1897, the Company under their powers served notice on the Churchwardens, and shortly afterwards took possession of the church and carried on their works. These works had been in progress nearly three years, and all the Company had done was strictly within their rights. On the lands they had made approaches to the station, which was formed of the crypt of the church, and was 4ft above ground level. So far as the engineering went, it was a wonderful piece of work”.

It was indeed a wonderful piece of work. The church lost its crypt, which became part of the station infrastructure for the City and South London Railway, and the church above ground was strengthened with steel reinforcement.

Most importantly, it was a compromise which ensured this unique Hawksmoor church would survive.

The side of the church facing King William Street is now masked by what was the former Underground Station, designed by Sidney R.J. Smith and built between 1897 and 1898 as part of the works described in the Standard article above.

The Pevsner “London: The CIty Churches” does not think much of the facade, describing it as “a Hawksmoorish rusticated centrepiece, let down by mediocre flanking figures in low relief”.

The arch on the right provides access to a lift for step free access to the Northern Line platforms – the old City and South London Railway.

The churchwardens probably regarded the loss of the crypt as an extremely good result as only a few years earlier the church had to be closed because of the state of the crypt. This also sheds light on what an appalling state most City churches must have been in during the 19th century until their crypts were cleared. The following article explains:

“One of the oldest churches in the City of London has actually had to be closed in consequence of the effluvia arising from the dead bodies in the vault. This is St Mary Woolnoth. The congregation who worshiped there were not only annoyed, but made ill, and the clergyman, after the three services, generally went home with a sore throat. At times there would be no smell in the church, at others an intolerable odour came up in whiffs and gusts. It is computed that the remains of between seven and eight thousand bodies are massed together within a few feet of the floor”.

So the City and South London Railway fixed the problems with the crypt and the churchwardens received back a strengthened church, although now without a crypt.

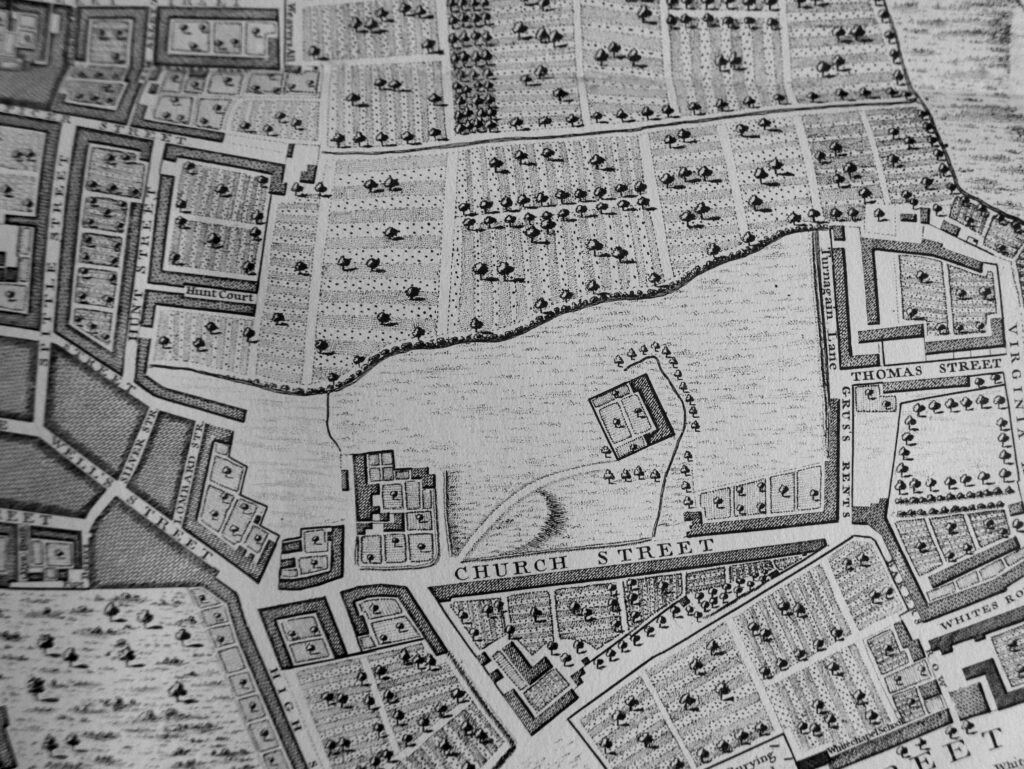

The article mentions that the church is one of the oldest in the City. There appears to have been a church on the site in the 12th century. The church was rebuilt in 1438, and it was this church that was badly damaged in the Great Fire.

There are a number of explanations as to the name “Woolnoth”. Pevsner states that the name “probably commemorates an 11th century founder named Wulfnoth”. Wilberforce Jenkinson in London Churches Before The Great Fire (1917) links the name with the wool trade.

This print from 1812 also associates the name of the church with the wool trade stating that “the distinctive term arises from the Wool Mart being near”.

The side view of the church in the above print shows how narrow the tower is from the side, compared with the width of the front view.

Another view of the church from around 1830 with a good view of the clock.

The interior of St Mary Woolnoth is relatively compact, Three large columns on each corner support a square opening, above which there is a space with an arch shaped window on each side, with a chandelier hanging from the centre of the ceiling.

Surrounding the altar is some impressive woodwork, with two ornately carved columns supporting a canopy decorated with gilded cherubs.

View up to the roof. It was overcast on the day of my visit, and the windows do not let much natural light through to the church interior below.

The organ gallery and organ case above the entrance to the church. According to the Pevsner guide, the organ case dates from 1681, so perhaps it was part of the post Great Fire restoration of the medieval church, and was saved for use in Hawksmoor’s church.

In a corner of the church is a clock mechanism:

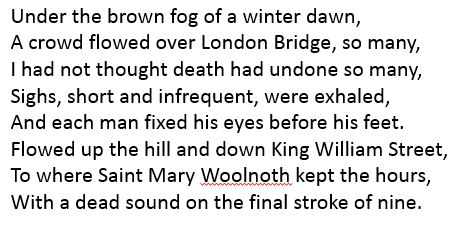

The mechanism is within a perspex cover, and just below is printed an extract from The Waste Land by TS Eliot:

Thomas Stearns Eliot was an American who moved to England in 1914 when he was 25 and became a UK citizen. In The Waste Land, Eliot is concerned about the state of Europe in the 1920s and the impact the modern world is having on the cultural, spiritual and moral state.

He worked in the City for a bank, so must have known the area well, and the description is of City workers flowing over London Bridge, up and down King William Street as they make their way to work, with the clock at St Mary Woolnoth reminding them of the time they needed to be in their offices.

Although written in the 1920s, it is a scene that could still be seen up until March of this year, and I suspect Eliot would be just as concerned today as he was then about the moral state of the world.

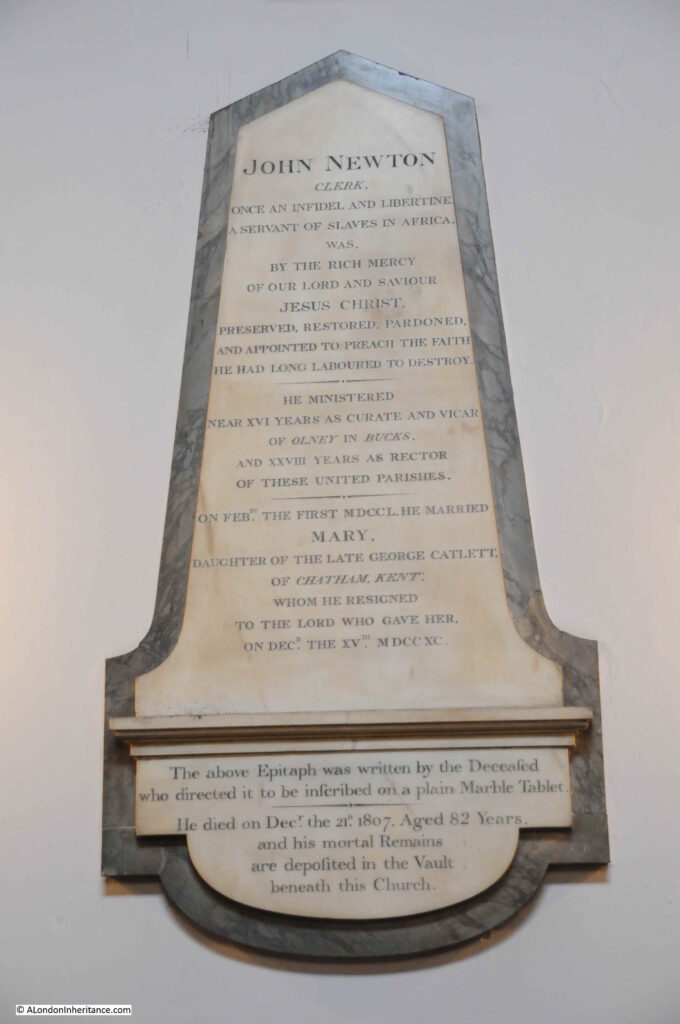

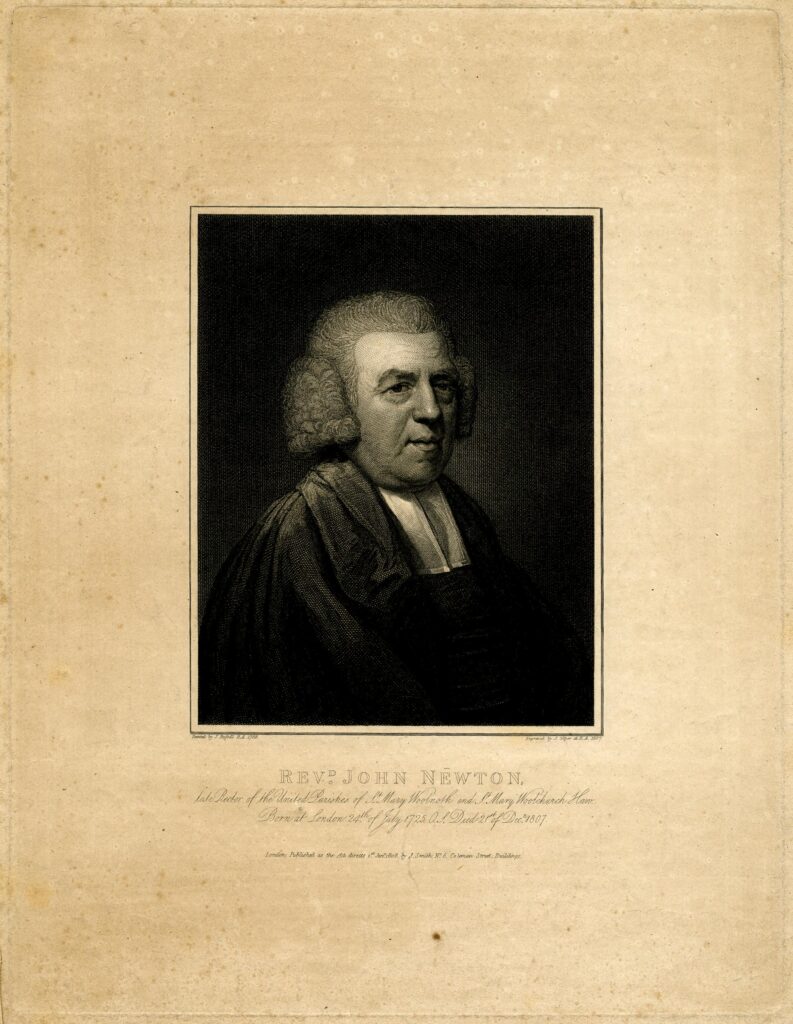

St Mary Woolnoth has a memorial to perhaps the most celebrated rector of the church, John Newton:

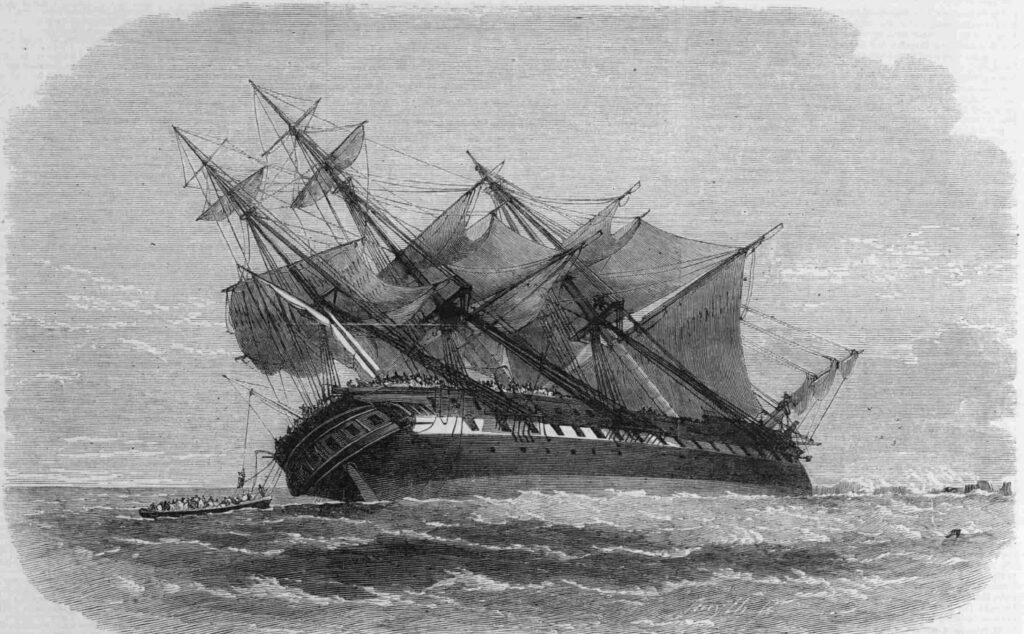

John Newton was born in Wapping in 1725, the son of a Master Mariner, so his life at sea was as good as guaranteed. His early career at sea was in the slave trade, working on slave ships, including three voyages as captain. In 1748 he converted to Christianity and from the same year worked as the Surveyor of Tides in Liverpool. During his time in Liverpool he studied theology and although considered a radical, finally found a position as curate at the church of Saints Peter and Paul in Olney, Buckinghamshire.

Whilst he was at Olney, he worked with the poet William Cowper on a collection of hymns which included Amazing Grace.

His time at St Mary Woolnoth started in 1780 when he became rector of the church. During his time at the church, he supported William Wilberforce, he published a pamphlet titled “Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade” in which he wrote about his time as a slave trader, wrote about his regret of his role and was outspoken in his condemnation of the slave trade.

He supported the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade which had been formed in 1787, and the committee purchased copies of Newton’s pamphlet to be sent to every member of the House of Commons and the House of Lords

John Newton provided evidence to the parliamentary committee set up to examine the slave trade, and used his experience as a slave trader to speak about the appalling conditions of the trade.

The law to abolish the slave trade, the Abolition Act passed into law and soon after, in December 1807, John Newton died. He was buried in the crypt of St Mary Woolnoth, alongside his wife.

When the crypt was cleared for the construction of the Underground station, the bodies of John and his wife Mary were moved to the church in Olney where he had been churchwarden.

Newton’s pamphlet “Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade” provides a very clear account of the unbelievable cruelties of the trade and makes for a very harrowing and upsetting read.

The Cowper and Newton Museum in Olney can be found here, and they also have a copy of the pamphlet in PDF form which can be downloaded from the following link:

https://www.cowperandnewtonmuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/thoughtsuponafri00newt.pdf

The Reverend John Newton:

St Mary Woolnoth is an important church. A church has been on the site since the 11th century. Architecturally, it is a fine example of Hawksmoor’s work. The church survived the arrival of the Underground railway and suffered minimal damage during the blitz.

Many millions of City workers must have looked up at St Mary Woolnoth’s clock on their way to and from work, and from John Newton we can learn first hand about the appalling cruelties of the slave trade.