The end of February marks the end of my 8th year of blogging, so time for a bit of a ramble through some of the themes of the past year, and how these have had an impact on London.

But first, a couple of blog admin comments. Firstly e-mail,

When I set up the blog in 2014 I used all the default WordPress widgets including one for “Contact” where the e-mail address was displayed, and could be clicked on to launch an e-mail client. The problem with this approach was that the address was easily discoverable and found by all the spammers who pollute the Internet.

The original blog e-mail was full of e-mails with dodgy links, attachments full of viruses, all the usual messages trying to fish for bank account details, etc.

There was so much that I have missed many genuine e-mails, so my apologies if you have messaged and I have not replied.

I have now changed to a Gmail address and this can be found down the lower right of the home page of the blog, displayed as a picture, so whilst not as convenient to use, it should stop much of the spam the old account received.

I have also added a “Blog roll” down the lower right of the home page. This is a listing of other blogs, or sites which may be of interest. I will be adding more in the coming weeks.

A London Inheritance Walks

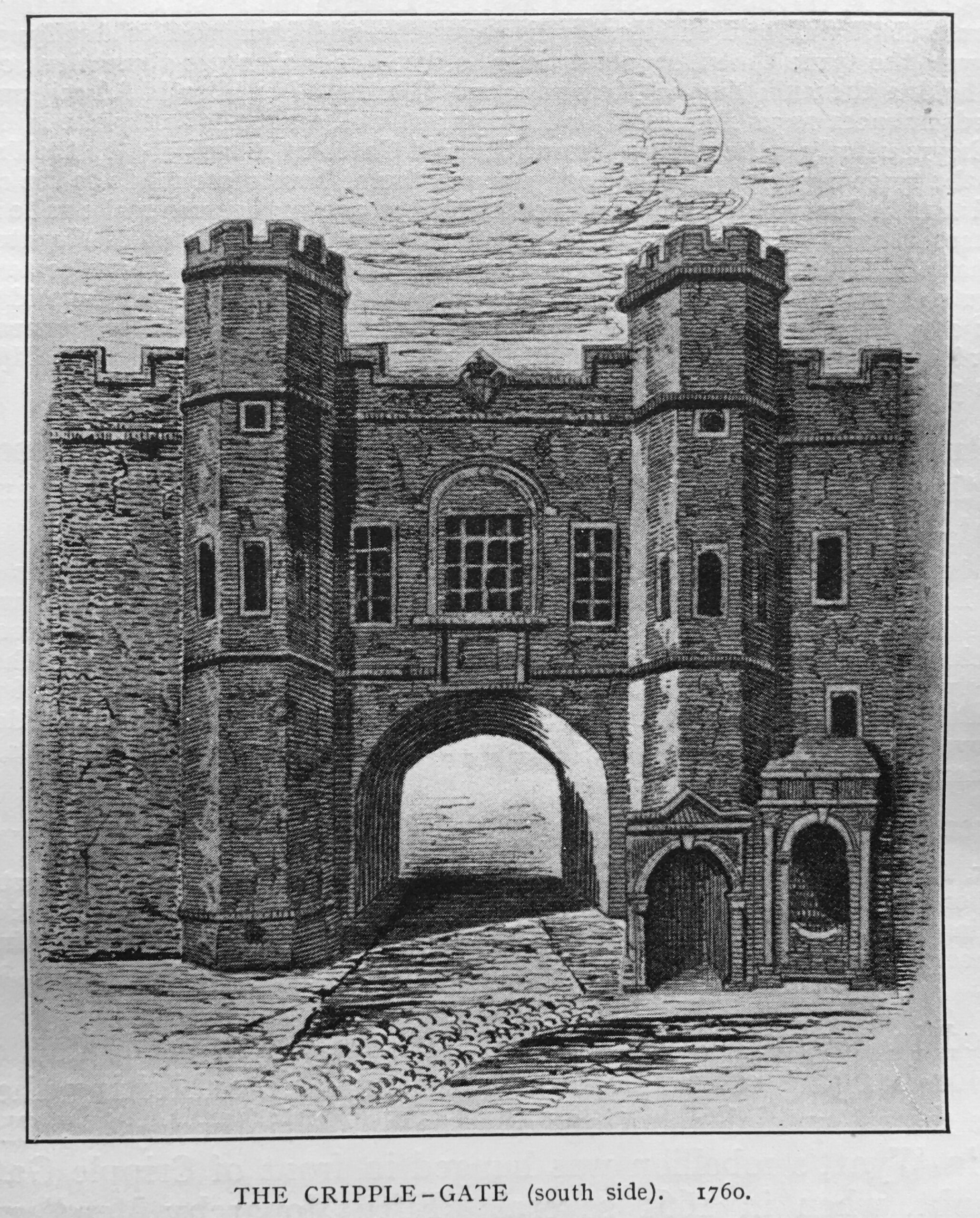

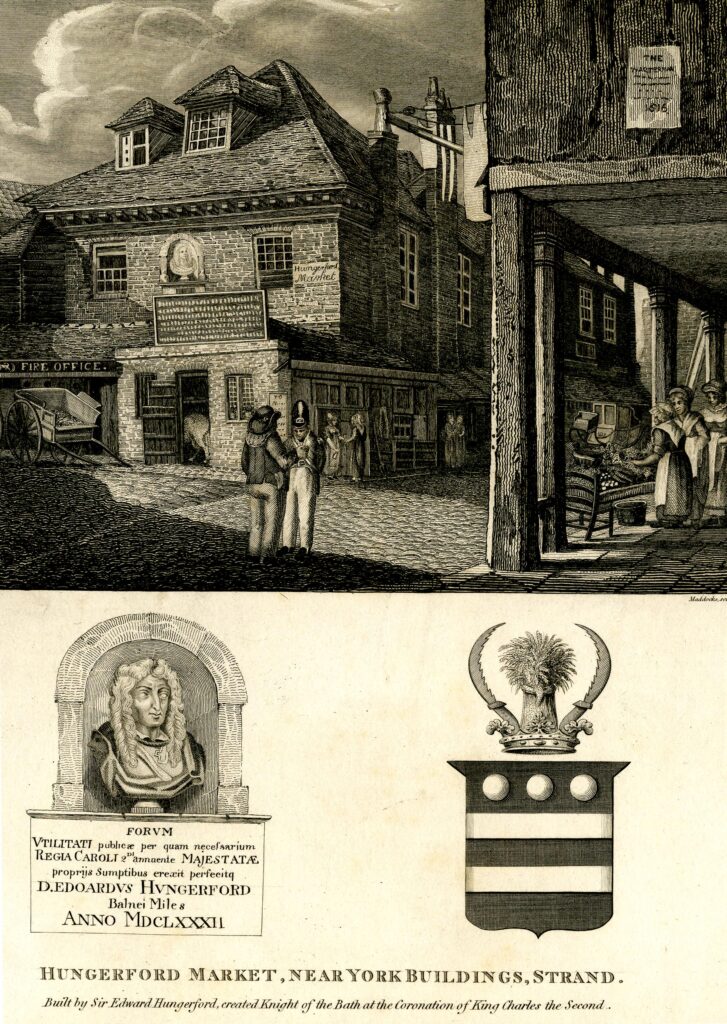

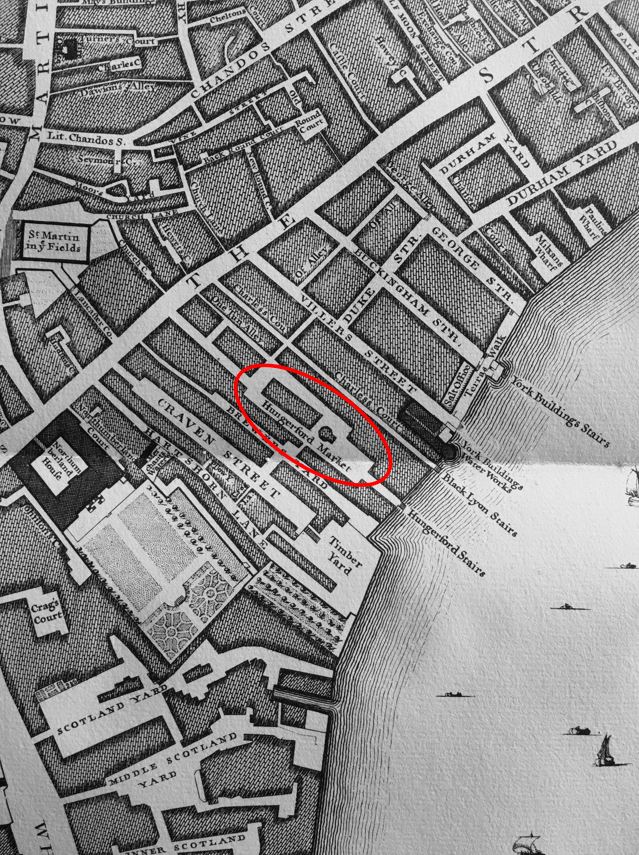

The main blog related event for me during the past year, was the start of my guided walks. Two walks, one covered the South Bank and the other the Barbican and Golden Lane Estates. The walks were a sell-out and it was brilliant to meet so many readers, and my thanks to all who came on a walk.

I have been working on three new walks which will follow the same format, and will cover Bankside, Bermondsey and Wapping, as well as continuing the South Bank and Barbican walks.

I plan to have dates advertised from late April. They will be on the blog, and for early access to all dates, you can follow my Eventbrite page here.

Swanscombe Peninsula

Last September I visited the Swanscombe Peninsula, a large area of land that pushes out into the River Thames, to the east of the city.

The peninsula is under threat of development with the London Resort proposals for a large theme park to be built on much of the land.

The Swanscombe Peninsula has a long industrial heritage, but is now mainly marsh and grasslands. Walking the area provides a wonderful feeling of walking an isolated and natural section of north Kent, an environment that is all the more important as London pushes east along the river.

The Swanscombe Peninsula is an important site of biodiversity, with wetlands and marsh occupying significant parts of the space,

A key decision that may impact whether the London Resort goes ahead, was the decision last November by Natural England to confirm the peninsula as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, and in their announcement stating:

Natural England has today confirmed Swanscombe Peninsula as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in recognition of its national importance for plants, geology, birds and invertebrates – including one of the rarest spiders in the country.

A valuable green space abundant in wildlife lying close to major urban areas, the 260 hectare site alongside the Thames Estuary forms a corridor of habitats connecting Ebbsfleet Valley with the southern shore of the River Thames between Dartford and Gravesend.

The Natural England Press Release can be found here.

It remains to be seen whether confirming the site as an SSSI is sufficient to stop the proposed development, but it was a very hopeful step.

New River Walk

In October, I walked the first part, from Ware to Cheshunt, of the New River Path, a walk that follows the 17th century New River from source near Ware in Hertfordshire to New River Head in Islington (the final part from the east and west reservoirs around Woodberry Wetlands, just south of the Seven Sisters Road to New River Head being a heritage walk along the route of the river).

It was a fascinating walk, along manmade infrastructure and 19th century pumping stations that are still key in providing water for London’s growing population.

Hopefully, in the coming weeks, I will complete the remainder of the walk from Cheshunt to Islington.

The Changing Face Of London

The face of London continues to change with what seems a continuous stream of new glass and steel towers. Last May, I wrote about Three Future Demolitions and Re-developments, one of which was the old ITV Studios on the South Bank (the square tower in the centre of the following photo):

The building is now securely fenced off, and scaffolding surrounds the lower buildings and appears to have started creeping up the tower. presumably in preparation for demolition:

Coin Street Community Builders and the Waterloo Community Development Group have organised a petition in opposition to the planning application. Their page on the proposal can be found here.

Meanwhile, the transformation of many of the city’s buildings to either expensive apartments or hotels continues. I was in Westminster on Friday and the old War Office building is now being transformed into the “OWO Residences”, and “London’s first Raffles Hotel”, which will offer “Privileges and Amenities Beyond Compare” which gives an idea of the price range and target market.

The former War Office building really is in a prime position, on Whitehall and opposite the Household Cavalry Museum and the tourist trap in front of the Horse Guards building.

The Grade II listed old War Office building:

The only constant in London is the level of change, however it does seem that so much local identity is being lost. There must have been so many other creative uses for such a building. I wonder what has happened to the tunnels that once connected to the building.

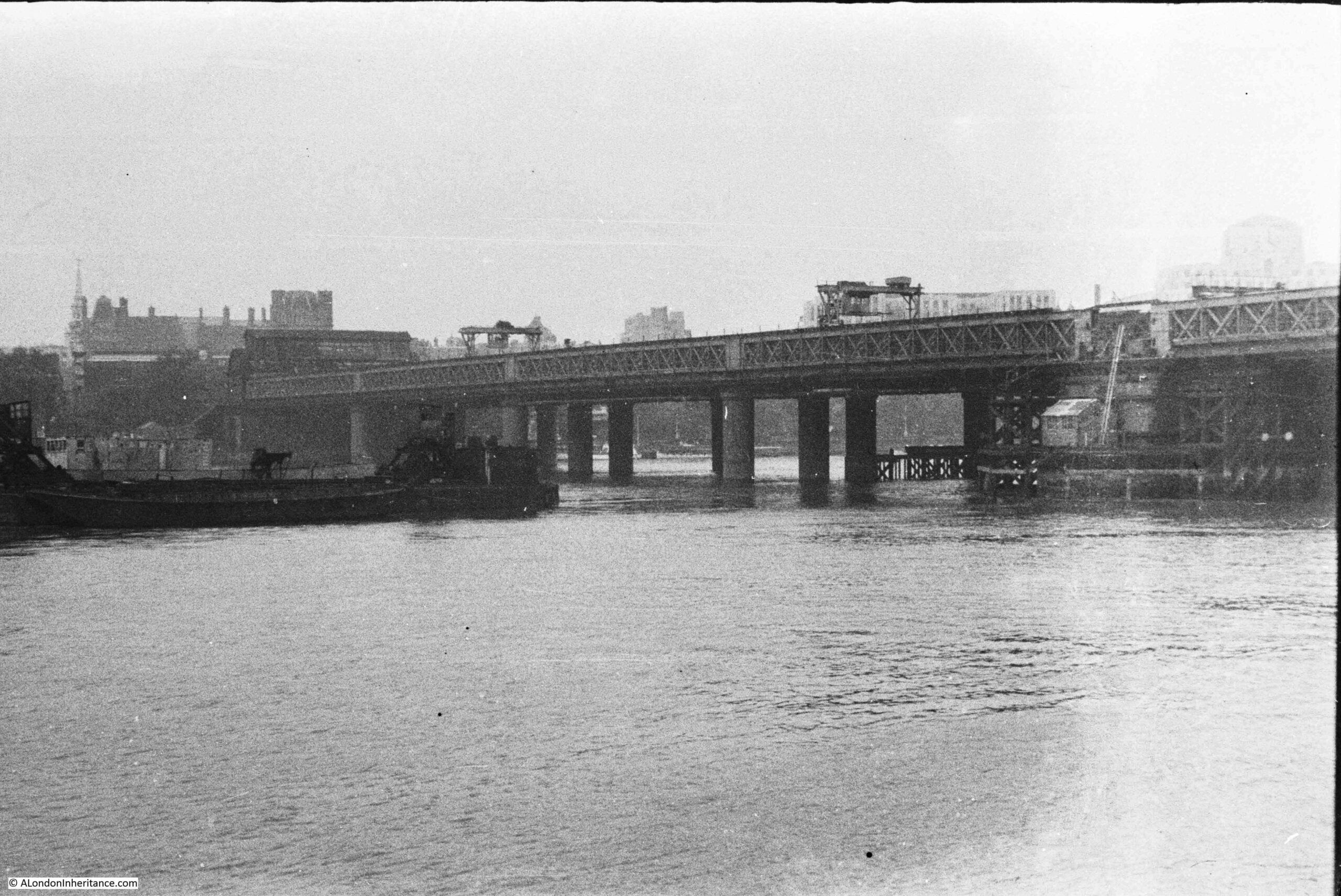

My Father’s Photos

The original aims of the blog were rather selfish. To provide me with an incentive to find the current locations of my father’s old photos, and to find out more about London, which I had probably taken for granted for too many years.

I featured more of my father’s photos during the last year, one of my favourites was the following photo of an art exhibition in 1952 in Embankment Gardens:

The same view today:

I have many more of my father’s photos still to go, and there is so much else of interest in London, so hopefully the blog will be still be going for a few more years.

London is fascinating to explore, but sometimes it is just good to sit and watch. Whilst walking through Bankside last year I noticed a couple had moored their boat in the river and were reading and looking at the view.

Not a bad way to spend a Sunday morning.

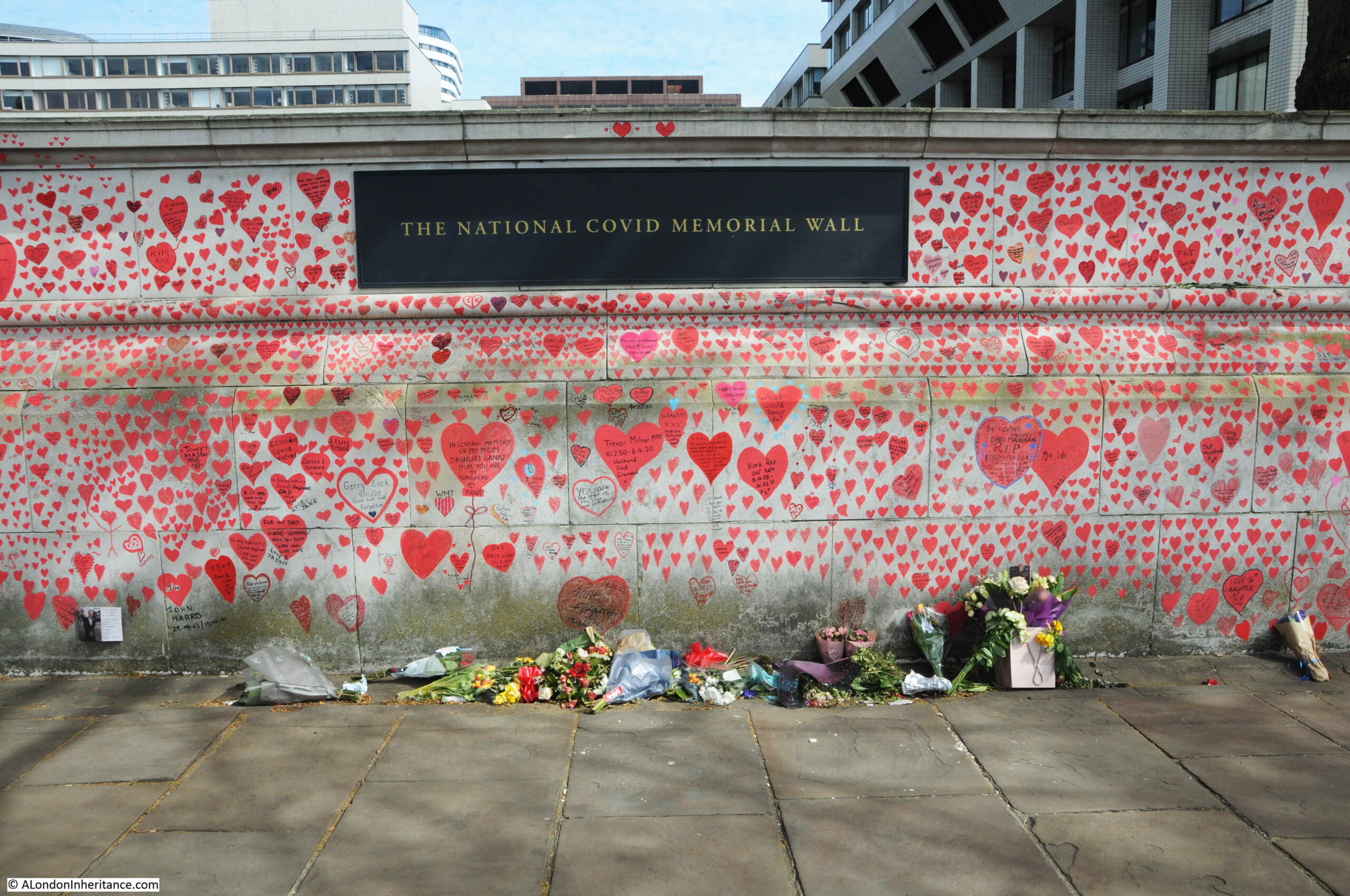

The National Covid Memorial Wall

For a second year running, Covid has had a significant impact on London. The impact to businesses, significantly reduced tourism, working from home, etc. all have a visible impact on the city, however the hidden tragedy is the number of deaths.

The daily release of figures of deaths and infections become hard to grasp. Last Friday’s figures identified another 120 deaths.

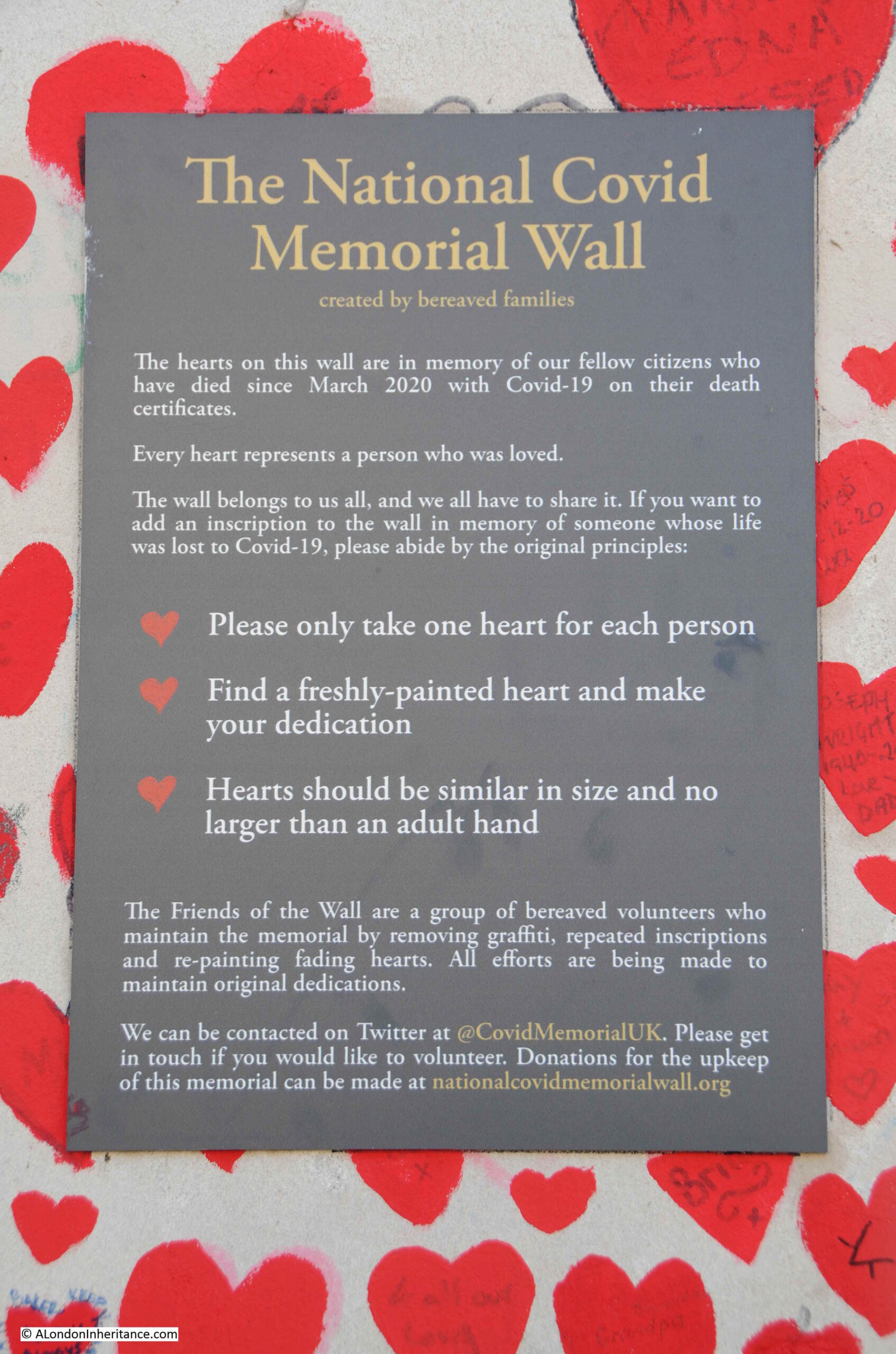

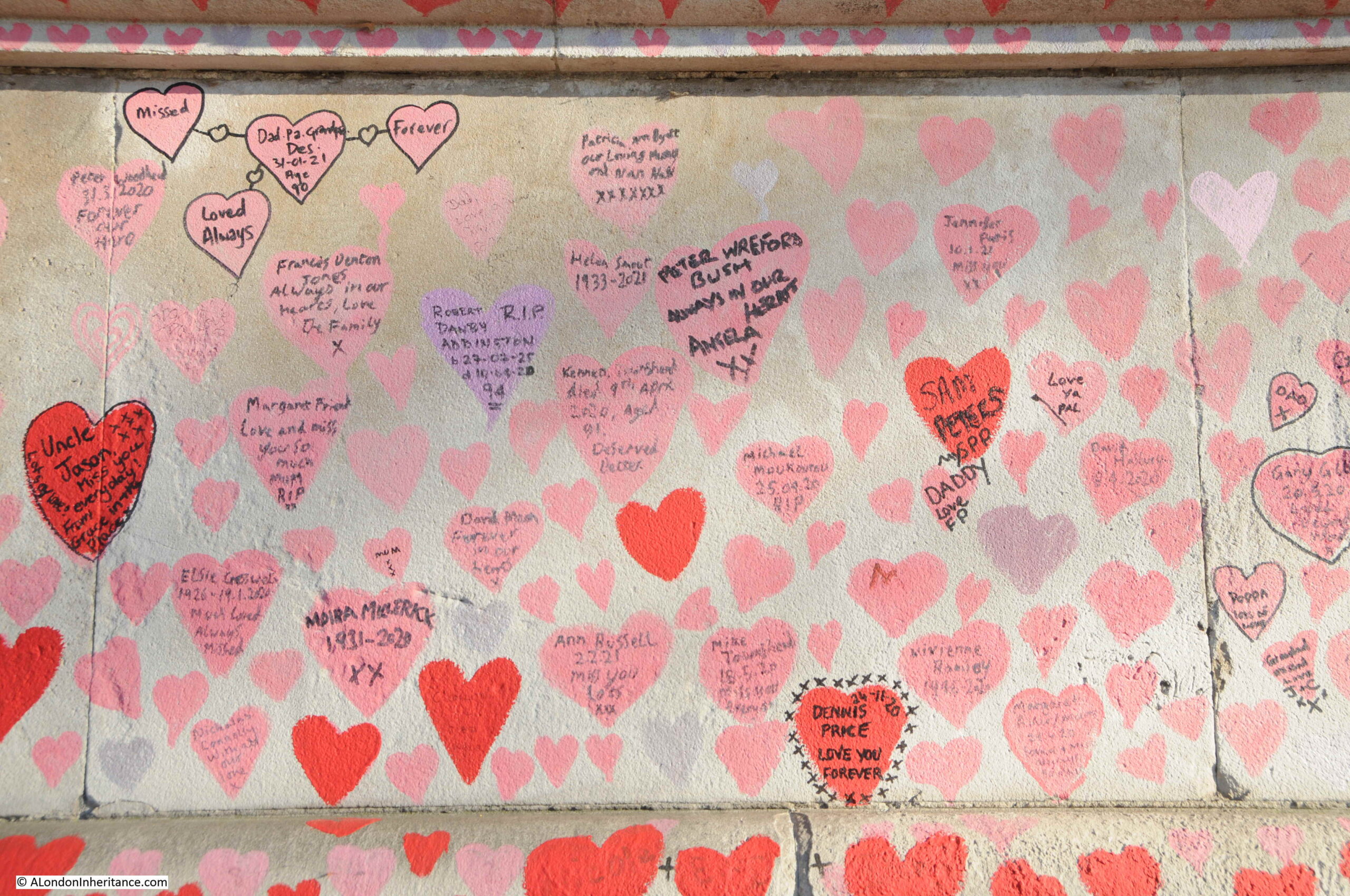

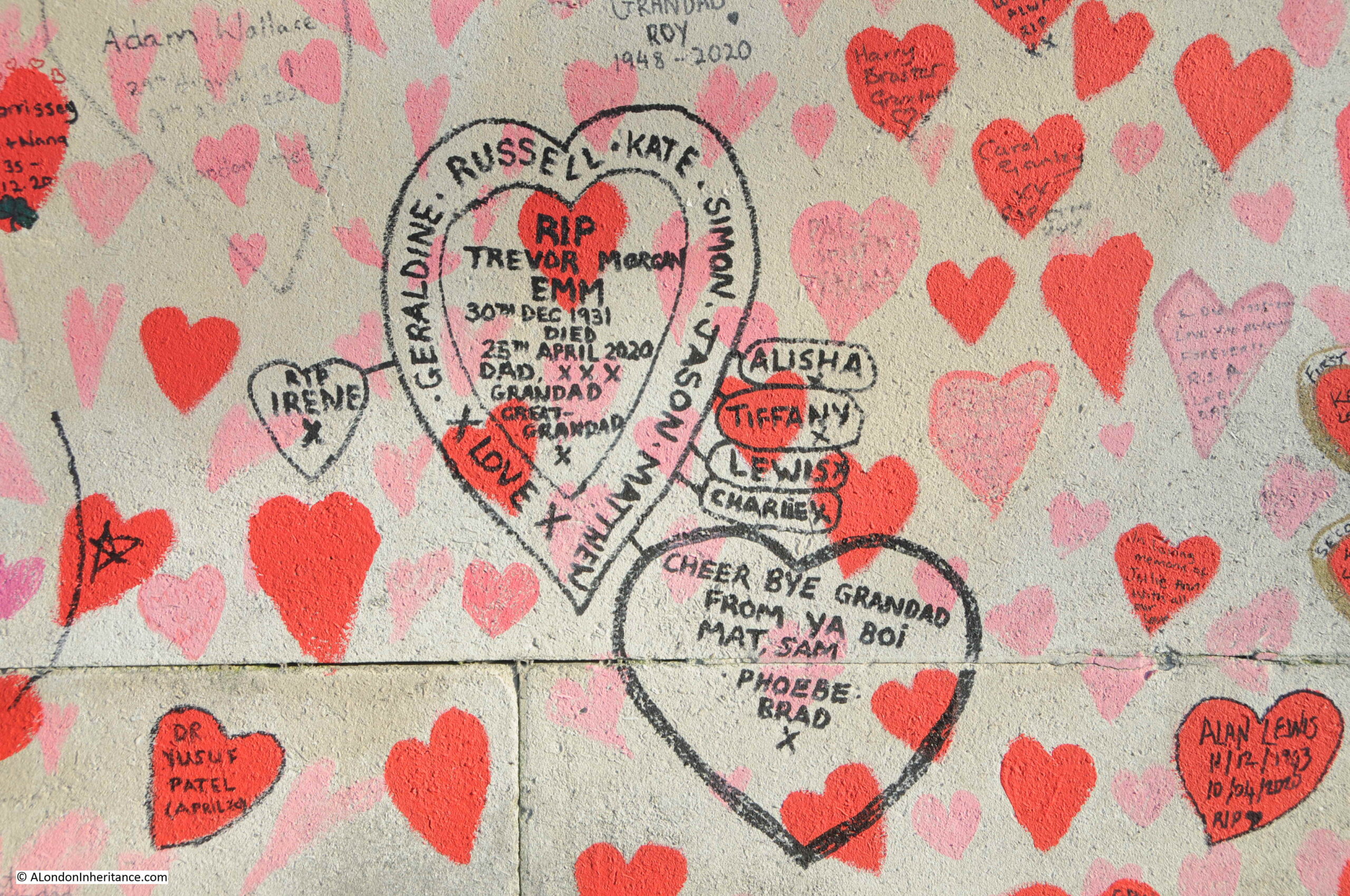

The National Covid Memorial Wall, along the embankment opposite the Palace of Westminster, between Westminster and Lambeth Bridges, really brings home the impact of these figures, with each heart along the wall representing an individual death.

The memorial was created by 1,500 volunteers starting on the 29th of March 2021, coordinated by Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice, and Led By Donkeys. Further information on the wall can be found here.

The memorial wall stretches almost the entire length between Westminster and Lambeth Bridges:

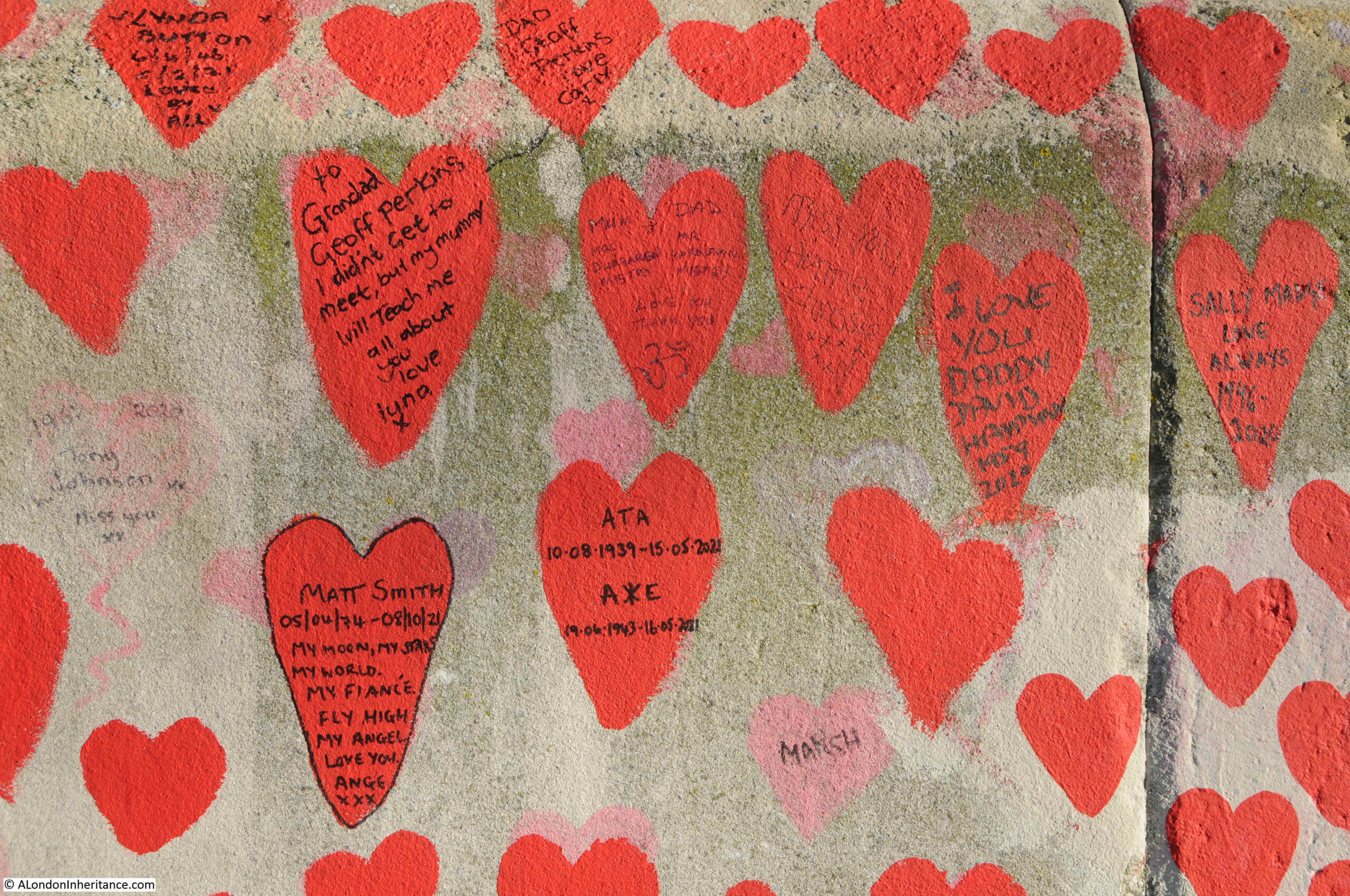

Each of the hearts represents an individual death. Families have added the names of those who have died to many of the hearts which really brings home that the daily figures represent the loss of an individual, and the impact on their family.

There are calls to make the wall a permanent memorial, however I suspect this Government will want to move on very quickly from the previous two years.

The City of London

Whilst much of London is almost back to “normal”, the City of London is still very quiet compared to pre-pandemic days. Much of this can probably be attributed to the attractions of working from home for at least part of the week. Why spend a fortune on commuting, frequently in a crowded commuter train, when you can work at home for a few days a week.

Back on the 3rd of August 2021, the Evening Standard was telling older workers that apparently they had a “duty” to go back to the office:

The impact on Transport for London has been considerable. Probably the only transport system in a capital city that has to rely on fares for the majority of its revenue.

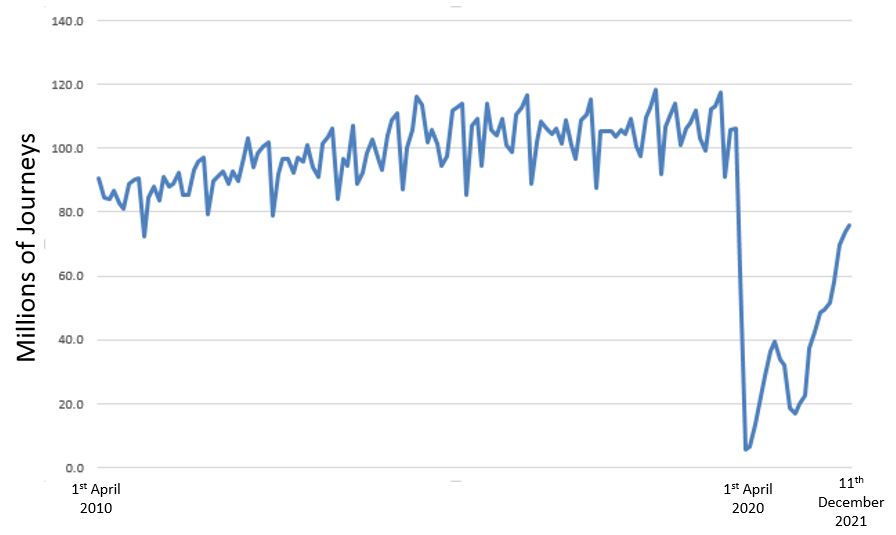

The latest data from the London DataStore, runs up to December 2021 and shows the impact of the last couple of years on travel on the Underground.

I downloaded the data and created the following graph, which shows how travel on the Underground has gradually been rising over the ten years from April 2010 to 2020, and then fell off a cliff at the start of the first lock down.

The above graph uses monthly data, and shows the peaks and troughs of travel patterns through the year, and also that travel volumes have still not returned to their pre-pandemic numbers.

Where a system is so dependent on fare revenue, the graph shows the impact on TfL’s finances and why Government support is needed. The challenges of negotiating this when you have a Labour London Mayor and a Conservative National Government have resulted in only short term solutions, rather than a long term agreement on how London’s transport can be funded for both day to day running costs and future investment.

The impact on the City can be seen walking the streets. There are a number of businesses that are dependent on people, such as cafes, restaurants, dry-cleaners etc, which have closed.

This includes the Cards Galore shop on the corner of Cheapside and Wood Street. (I wrote about the location in September of last year):

The core of the City is strangely quiet. There is hardly any traffic in Cheapside, as from close to St Mary-le-Bow, the street is closed to traffic apart from buses and cycles:

This appears to include taxis, as whilst walking from Cheapside to Liverpool Street I did not see a single black cab. There was a queue of people waiting for a taxi at Liverpool Street, so I assume taxis in this area are in short supply, perhaps due to the number of road closures.

There are far more people walking the City streets than there has been for the last couple of years, however the City just seems so quiet, more like a Sunday than the working week.

The Bank Junction where only buses and cycles are allowed:

I am in two minds regarding the changes to the City’s streets. It is possible to stand in the middle of the street and take photos, air quality is much better, however the City seems to have lost something which made the City – the City.

The City of London has always been busy during the working week. Pavements busy with people, roads with cars, vans, taxis and buses. That was part of the attraction, what made the City of London unique and different to the rest of London. A busy centre of trade and finance, and in the past, industry and markets.

Looking down Lombard and King William Street:

Other planned changes for the City include the move of Smithfield Market to Dagenham Dock, far to the east of the City, where Billingsgate, New Spitalfields and Smithfield markets would be consolidated into a single site.

Smithfield is the last wholesale market in central London and would be a further change to the historic functions of the City. Many of the tenants are not happy.

Looking back over the Bank junction to Queen Victoria Street and Poultry:

View down Old Broad Street:

Old Broad Street on the left and Threadneedle Street on the right:

In the background of the above photo are the glass and steel towers that continue to be built within the City – will there be enough office workers to support all the space?

It will be interesting to see how the City of London reinvents itself. Will it return to a pre-pandemic “normal” after a few years?

If not, what happens to all the buildings? Conversion to expensive hotels and apartments will contribute to the loss of the City’s distinct identity. Trading too much on tradition could turn the City into a museum.

The move of the Museum of London to the empty Poultry and General Markets in Smithfield is a good move, but what are the benefits to the history and culture of the City by moving the remaining market at Smithfield?

Then just when you think that the last two years of terrible news is coming to an end, Russia starts a horrific invasion of Ukraine.

Walking along Whitehall on Friday, there was a small group opposite the entrance to Downing Street:

And the news stands across the city continue to provide a record of historical events:

And with that rather rambling review of my 8th year of blogging, can I thank you all for subscribing, commenting and just for reading my weekly explorations of London, and if you feel like a guided walk later in the year, I look forward to meeting you.