One of my first posts, three years ago, was about flying over London in a vintage de Havilland Dragon Rapide. I took a number of these flights between 1979 and 1983 as I loved flying, I had started working so I could afford tickets and I had a reasonable camera.

I continue to scan my negatives and I recently found some more photos of flying over London from Biggin Hill, over east London and the City before returning to Biggin Hill. For today’s post, here are a selection of photos from the earliest (black and white) to the later years (colour) of flying over London in a de Havilland Dragon Rapide.

I will start with the earliest and you will see an improvement over the years in the cameras I was using.

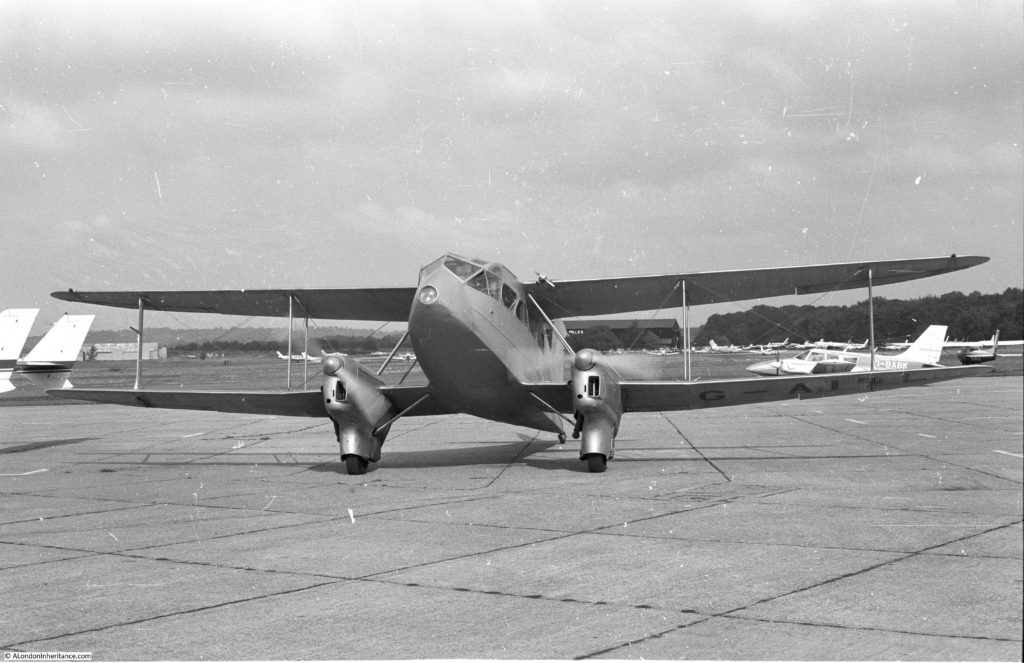

Firstly, here is the de Havilland Dragon Rapide. A design from the 1930s with this plane being manufactured in 1946:

The flights from Biggin Hill changed the routes taken to get from the airfield to the City each year which provided the opportunity to see different parts of south London. The flying height was low enough so that detail on the ground was clear, and the lower speed compared to jet aircraft allowed sufficient time to pick out the locations along the route.

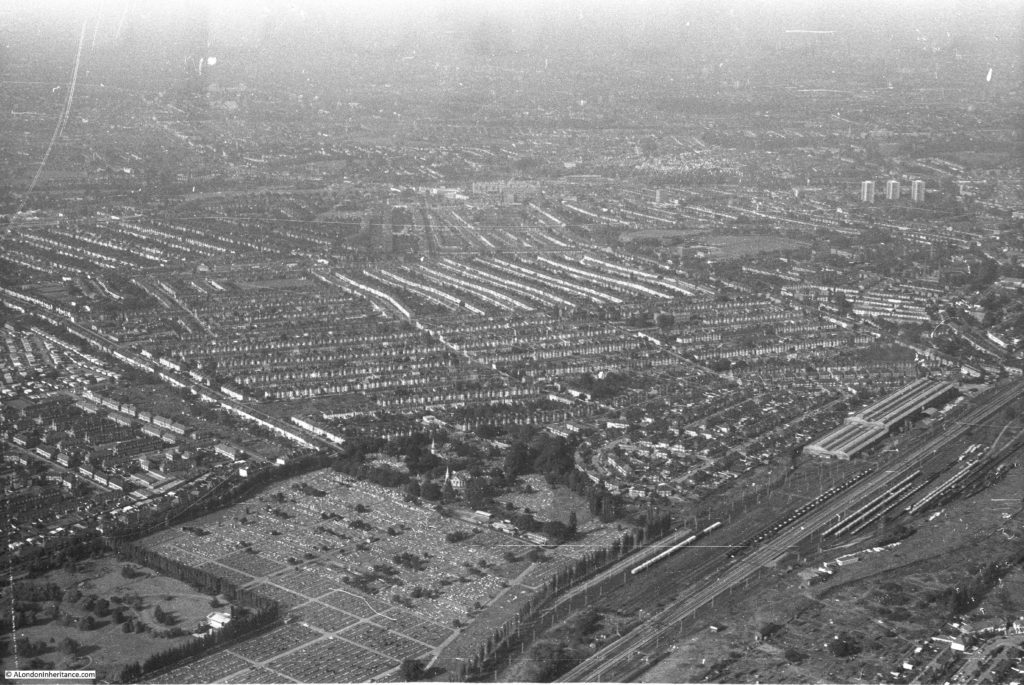

In the following photo, the large cemetery in the lower left of the photo is alongside Hither Green Crematorium, with Catford in the background of the photo.

Hither Green – the railway can be seen running from the bottom of the photo, just to the left of centre, with Hither Green station being roughly a quarter of the way up the railway line:

Bromley:

The distinctive loop of houses to the lower right of the following photo is the appropriately named Oval Road, just to the immediate north-east of East Croydon Station.

The next three photos are flying up to and over Rotherhithe and the land once occupied by the Surrey Commercial Docks. The Isle of Dogs can be seen across the river.

Moving on to a later year and I have changed to colour film and the flight from Biggin Hill has taken a slightly different route so we can see the Thames Barrier in the final stages of construction:

The northern end of the Isle of Dogs with from the top, the West India Dock (Import), the West India Dock (Export) and the South Dock. If you look just above the top dock, over to the right is the spire of a church, this is All Saints Church, Poplar. The Balfron Tower can be seen just behind the spire of the church.

Hard to believe that this is now the Canary Wharf development and One Canada Square is now in the centre of these docks.

Looking back over the Isle of Dogs. Limehouse Basin is the area of water in the centre of the photo.

Looking back over Limehouse Basin. The Limehouse Cut can be seen running from the top corner of the basin. The Regent Canal is the line running from the lower left corner.

The church of St. Mary the Virgin, Rotherhithe is clearly visible in the lower part of the following photo. Shadwell Basin is across the river.

Approaching the City:

In the following photo, the railway line into Liverpool Street Station is running from lower right to top left of the photo. The grassed area in the centre of the photo is Weavers Fields, Bethnal Green.

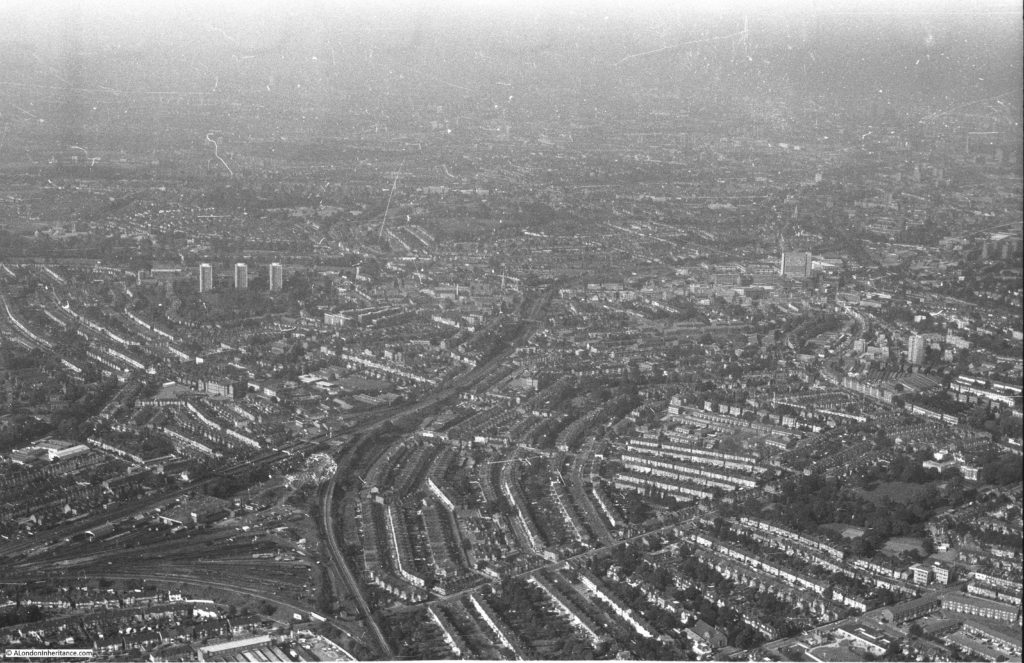

Another view looking along the railway into Liverpool Street Station. Bethnal Green on the right, Stepney and Whitechapel on the left.

Approaching the City:

This was the view of the City when the NatWest Tower (now Tower 42) was the highest building in the City. It had just been completed when this photo was taken.

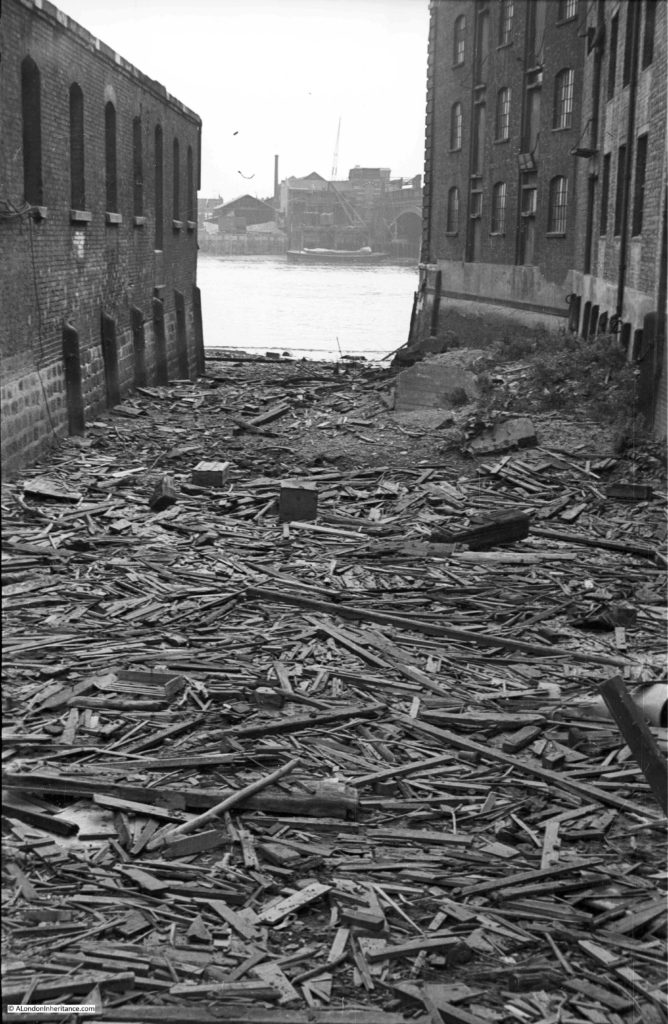

Flying over the river, looking west. This was before HMS Belfast was moored on the river and when warehouses still covered much of the south bank. Note the flying boat moored just north of Tower Bridge. This was a Shorts Sandringham – a remarkable sight to see on the river. The large white building on the north bank of the river is the old British Telecom Mondial House building.

Now for the final trip with a better camera and film, and a different route. The sports ground at Crystal Palace:

Slightly different angle on Crystal Palace. The tall Crystal Palace TV mast can be seen in the upper right of the photo:

Not sure where the next two photos are, somewhere over south London:

That may well be Croydon to the upper right:

The isle of Dogs again:

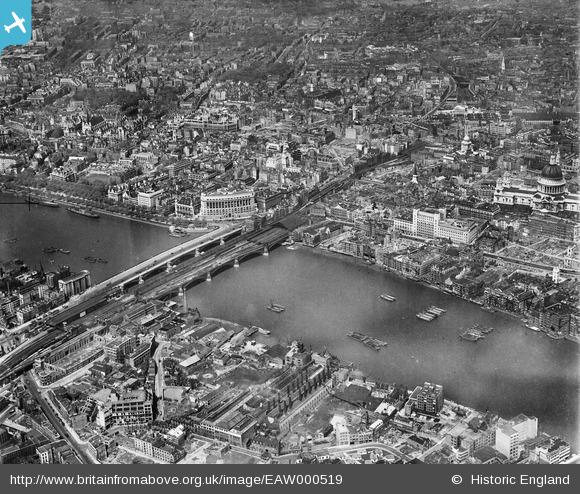

View looking over Bermondsey, Southwark and Lambeth with the railway running into London Bridge Station in the lower right quarter of the photo, long before the Shard.

View from over south London looking north. The River Thames is running across the middle of the photo from left to right. The green areas in the upper part of the photo are St. James’s Park, Green Park and Hyde Park.

Another photo looking from south London over towards the north west. Just to the left of centre is the old gas holder at Battersea. The chimneys of Battersea Power Station can be seen just to the right of the gas holder and Battersea Park behind.

View looking over the City:

The City of London, with still the Nat West Tower being the only really tall building. Note also how few cranes there are across the City. I counted about five in this photo. It would be very different now. The rate of construction has increased rapidly since the early 1980s.

Another view of the City.

HMS Belfast is now moored on the river.

A final view whilst crossing the river.

These flights let me pursue my early interests in flying, photography and London all at the same time. Unfortunately I have not taken any similar flights since the early 1980s. My aerial views of London now are when I have been working abroad and fly back into Heathrow. I always make sure I book a seat on the right of the plane in the hope that the landing will be from the east, and even after all these years, I am still the one with my camera pressed up against the window.