London provides plenty of opportunities for discovering the history of places that were once of significant importance, but now only have a faint footprint. There are plenty of these places outside of London, and whilst I catch up on the research for some London posts, for this Sunday, join me on a trip to a fascinating small museum on the shore of Southampton Water. The museum is all that remains of the Royal Victoria Military Hospital, Netley.

The Royal Victoria Military Hospital dates from 1863 and was built at a time when there seemed to be almost continuous wars, or skirmishes across the world as the Victorian view of Empire tried to establish and maintain dominance. The most recent major conflict being the Crimean War of 1853 to 1856.

On completion, the hospital was a quarter of a mile in length, and had 138 wards with the ability to accommodate over one thousand patients.

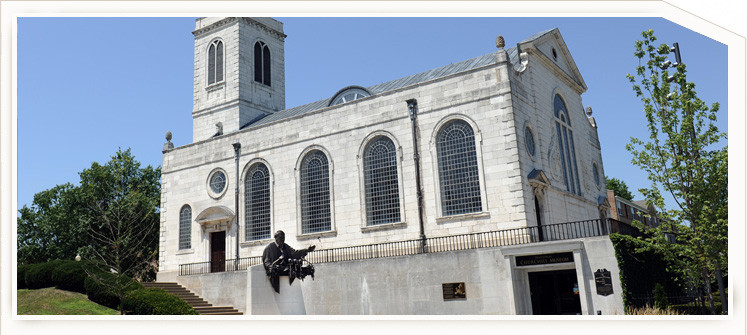

All that remains today is the original central chapel, shown in the photo above, and which now hosts a small museum dedicated to the history of the hospital. This chapel was once part of the central block, with two long wings of wards stretching to either side.

The following photo shows the Royal Victoria Military Hospital, soon after completion, from the end of the jetty that was built for the hospital, out into Southampton Water. The tower of the chapel can be seen in the centre of the photo and is all that remains.

The Royal Victoria Military Hospital was built at a site alongside Southampton Water for a number of reasons. Wounded troops would come from across the world on ships, along the English Channel, past the Isle of Wight and along Southampton Water to dock at Southampton.

This placed the hospital close to where potential patients would be arriving. A branch railway was constructed into the hospital grounds so that train loads of wounded troops could be efficiently moved from the docks directly to the hospital.

The hospital needed a large area to be available, and the space near the historic Netley Abbey provided room for the hospital, and additional land as the hospital grew.

The position facing onto Southampton Water was thought to provide benefits for both mental and physical health. The fresh sea air, the views across the water from grounds in front of the hospital were all expected to help with the recovery of patients.

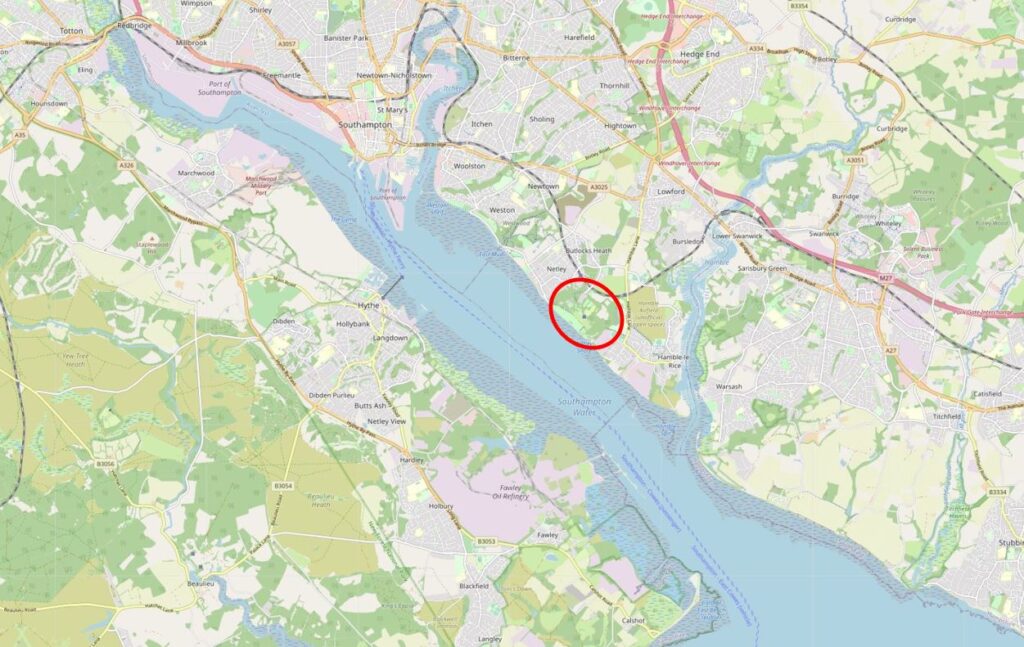

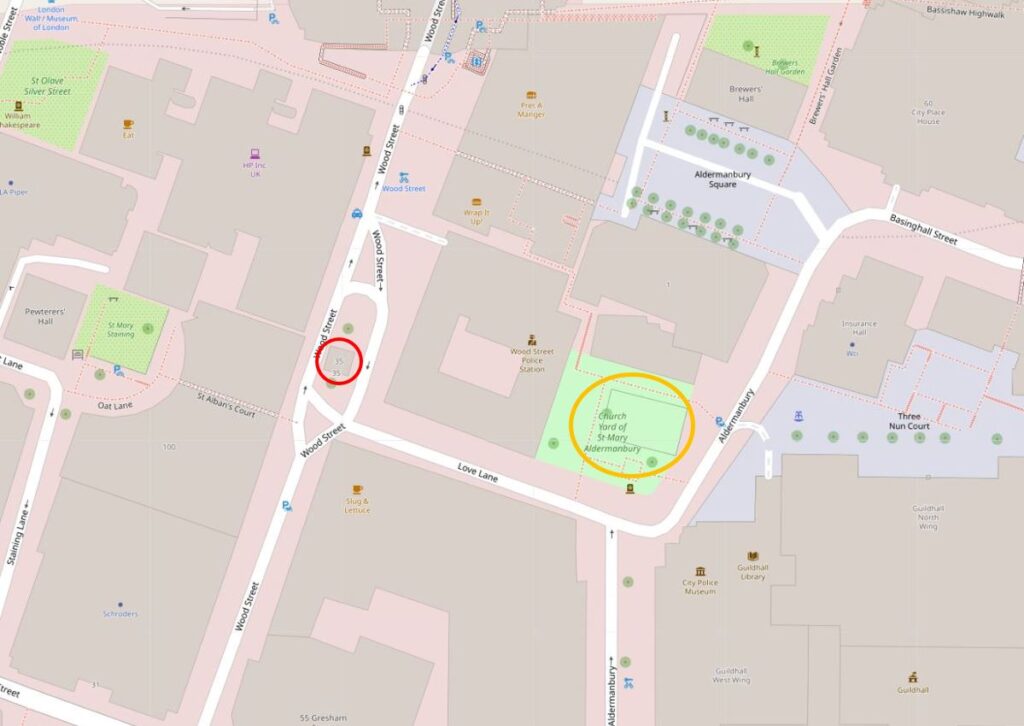

The following map extract shows the location of the Royal Victoria Military Hospital (ringed), alongside Southampton Water, with Southampton at the top of the map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The size of the hospital can be clearly seen from the air. The following photo, from the Britain from Above site, taken in 1923 shows the main hospital buildings (the chapel can be seen in the centre), the gardens down to Southampton Water, and the hospital pier

The chapel was a key part of the hospital, hence the chapel’s central position and the tower providing a central high point. Patients were encouraged to participate in services, and the chapel considered of rows of benches at ground level, with a surrounding gallery with tiered benches

The chapel forms today’s museum, and has been restored to much the same appearance as when patients were attending services in the chapel. The benches that covered the ground floor have been removed, and today replaced by displays covering the history of the museum.

The gallery has an interesting display featuring the history of individuals involved with the hospital as patients, medical staff or workers displayed along the benches.

Much of the drive for the hospital came from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Conditions for wounded soldiers in the first half of the 19th century were very basic. They were often housed in normal barrack buildings, with very poor sanitation and limited medical care. Disease and infection would often account for the deaths of more patients than their actual wounds.

Having visited a number of forts, Victoria expressed the concern that wounded soldiers were being treated in worse conditions than those for prisoners (which is saying something given the conditions of prisons during the first half of the 19th century).

The Queen also had the support of Albert, who saw the provision of improved medical treatment as one of the improving initiatives of Victorian Britain.

Based on her experience of the Crimean War, Florence Nightingale was also campaigning for improved conditions and treatment of wounded soldiers. During the Crimean War, British casualties consisted of 2,755 killed in action, but a much higher number of 17,580 died of disease.

A meeting between Nightingale and Victoria was an opportunity for Florence Nightingale to put before the Queen all the problems with the current system, and how badly wounded troops were treated.

Victoria wrote to Lord Panmure, the Secretary of State for War, who agreed that there should be improved general hospitals for the military, and a survey was initiated for a suitable site, and the Royal Victoria Military Hospital at Netley was the result.

Although the hospital was intended to be seen as a leading edge improvement in the treatment of the wounded, the design did not really follow leading thinking by those who had significant experience in the treatment of large numbers of casualties.

The Royal Victoria Military Hospital was designed with two large wings radiating from the central block (where the chapel was / is located). A corridor ran the length of the wings, and off the corridor were individual wards, sized to hold less than fourteen patients. Many of the wards were facing inland, so did not get a view across the gardens down to the water, or much access to fresh air. They were described as little more than cells for patients.

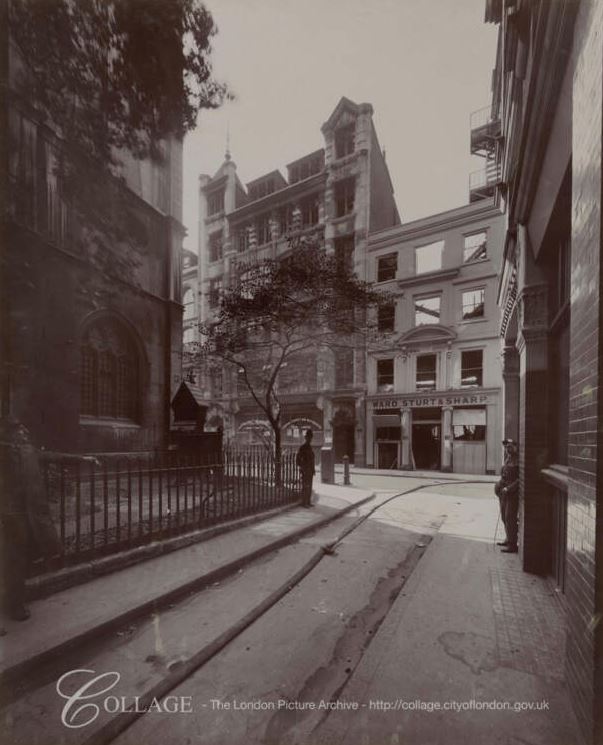

One of the corridors in the Royal Victoria Military Hospital:

Florence Nightingale was highly critical of the new hospital. Her experience and research had led her to believe that the best design for a hospital was for separate areas for different types of patient need, general medical, those undergoing surgery, and for those convalescing.

These separate areas needed to be of sufficient size to provide plenty of space for the patients, free airflow and good ventilation to provide patients with plenty of fresh air.

She was critical of the ward design at the Royal Victoria Military Hospital where she found small wards, facing away from the water with limited ventilation:

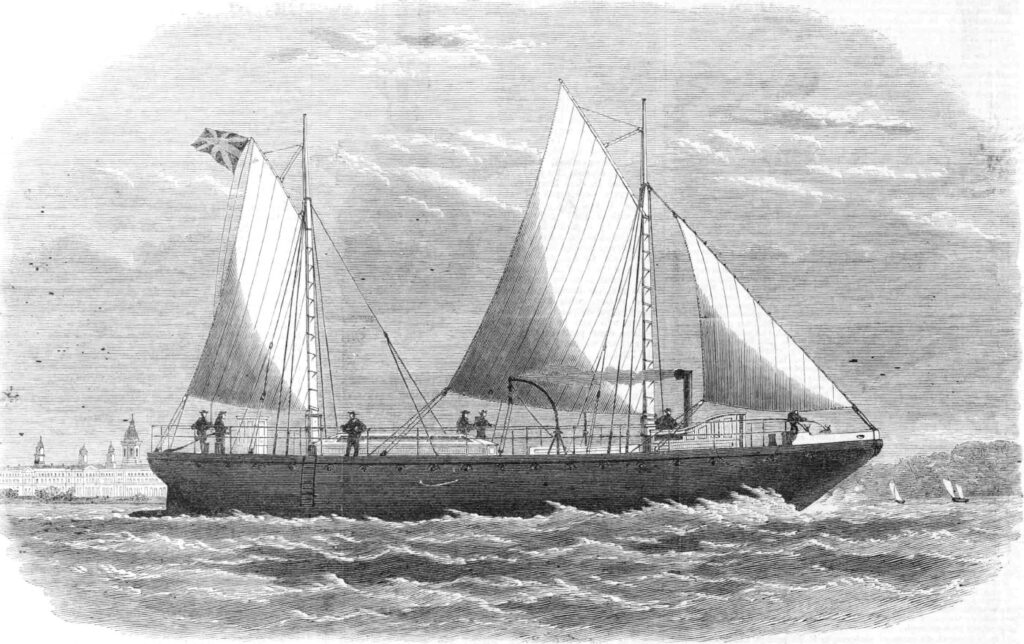

Queen Victoria maintained an interest in the hospital throughout construction of the hospital and throughout the hospital’s operation. When ever they were at Osborne on the Isle of Wight, described as the holiday home of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, they would take the short journey across the Solent and down Southampton Water to the site of the hospital.

Queen Victoria’s ship, with the hospital in the background:

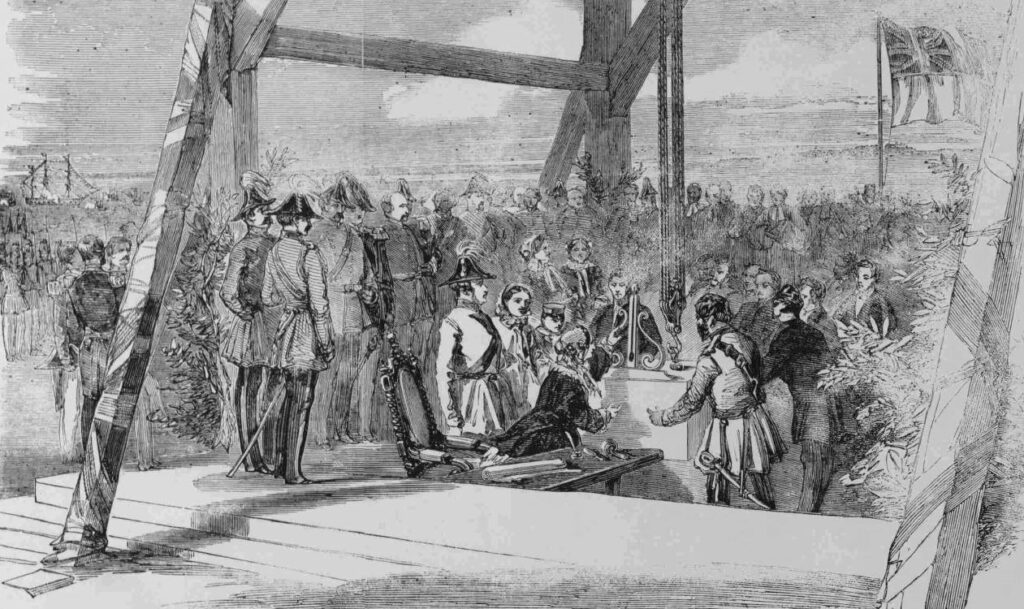

Queen Victoria laid the first stone of the new hospital in 1856. The newspaper reports described the scene, along with a tragic event during the ceremony that underlined the dangers that those in the army and navy were exposed to, even when not in battle:

“The Queen, Prince Albert, the Prince of Wales, Prince Alfred, and the Princess Royal, went on Monday to Hamble, on the Southampton Water, where her Majesty laid the first stone of the Royal Victoria Hospital, near Netley Abbey. After the ceremony had been performed, her Majesty inspected the troops employed on the occasion whilst at the dinner which had been provided for them. A sad accident occurred on board the Hardy, a screw gun-boat, two seamen, named Flanigan and Devine, having been killed while firing a royal salute. An inquest was held the next day, when it appeared that the accident arose from some burning fragments of the first charge being left in the gun and igniting the second charge. This was caused by defective sponging on the part of the deceased. The captain of the gun had his thumb over the vent at the moment, and it was blown off. Devine served in the trenches before Sebastopol, and was wounded by a shell at the storming of Malakoff. Flanigan had served in various parts of the world”.

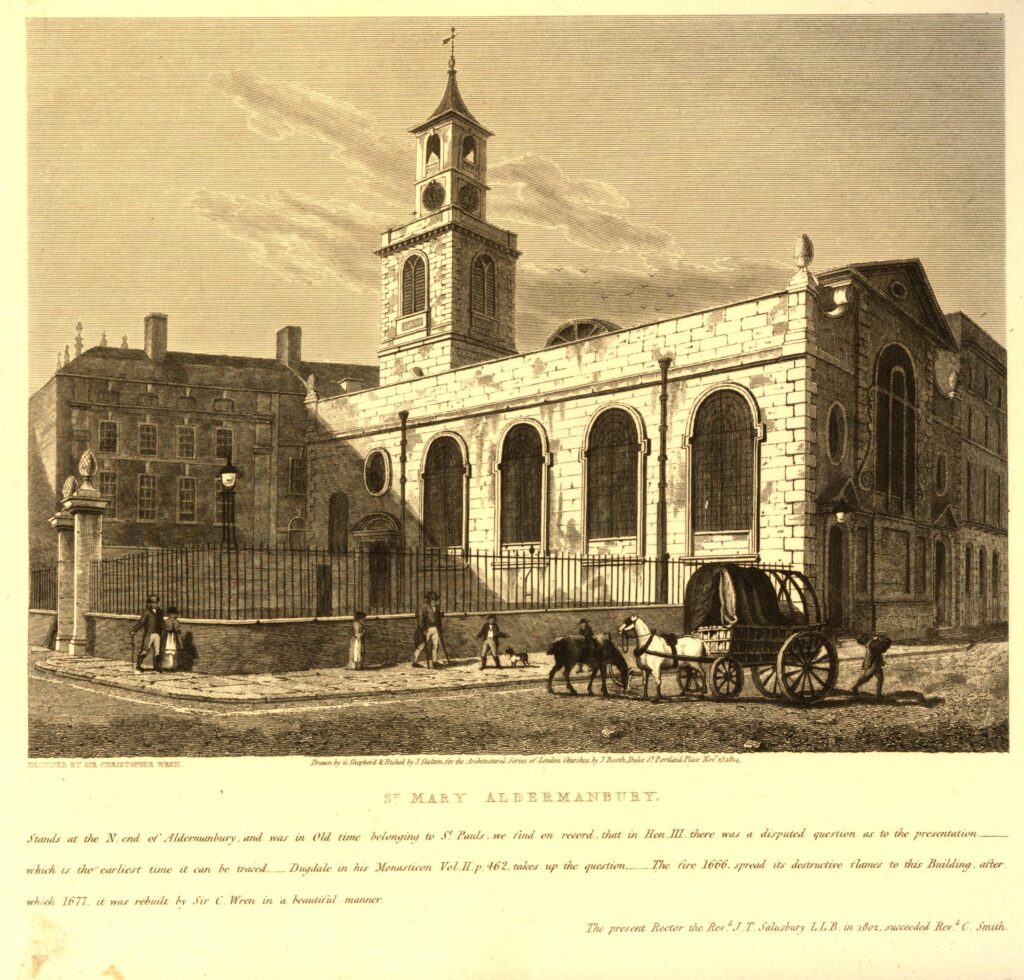

Laying the foundation stone of the Royal Victoria Military Hospital:

Prince Albert would not see the hospital fully completed, he died in 1861, however Queen Victoria continued to take an interest in the hospital, and a visit to the hospital in July 1863 was one of her first public outings since Albert’s death: “Her Majesty the Queen recently visited the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley, the foundation stone of which had been laid by the Prince Consort. This may be considered as the first public act of Her Majesty since her irreparable bereavement – an act every way very appropriate, as well as in accordance with her humane disposition”.

The Royal Victoria Military Hospital continued to grow over the coming decades, with additional facilities being built on the landward side of the hospital, including a psychiatric hospital which would attempt treatments for those suffering from the impact of war on their mental health, shell shock, and what is now recognised as post-traumatic stress disorder. Large numbers of shell shocked soldiers would be treated during the First World War.

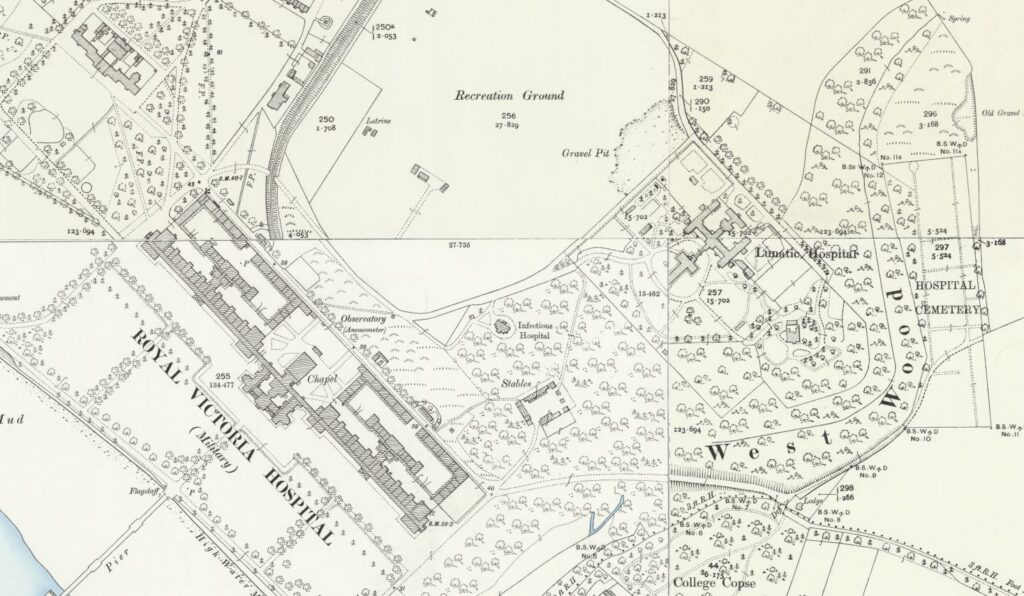

The following map extract from 1907 shows the size of the hospital, the railway line dedicated to the hospital coming in from the top of the map, the “Lunatic Hospital” to the right and the Hospital Cemetery.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

The number of patients at the hospital would reflect frequency and size of war’s that Britain was involved with around the world, with ships continuing to bring patients into Southampton for transport along the short distance to the hospital.

The size of the hospital was such that it was a significant landmark from Southampton Water, and one wonders how many troops leaving Southampton to fight abroad, would look at the hospital as they left, hoping that it would not be their destination on return.

The main hospital was demolished in the 1960s. It was a Victorian institution, and did not reflect the latest medical thinking when first built, so was very unfit for purpose in the later decades of the 20th century.

Countries of the former Empire were gaining their independence, so a hospital built to support the high number of casualties of the endless wars and conflicts that go with building and maintaining an Empire was thankfully no longer needed.

When Queen Victoria and Price Albert laid the original foundation stone, they also buried a time capsule, and when the hospital was demolished, there was much speculation as to the contents of the time capsule. The Daily Mirror on Thursday 8th December, 1966 reported:

“SECRET OF THE QUEEN’S BOX – the secret of Queen Victoria’s little copper box, buried 110 years ago, was revealed yesterday at a ceremony attended by eleven generals and an admiral.

The box was buried near the foundation stone of the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley, Hants.

Queen Victoria put articles in the box before she laid the foundation stone of the military hospital on a sunny May afternoon in 1856. The Army authorities never knew exactly what was in the box.

Now the hospital is being pulled down, and, at yesterday’s ceremony the contents were revealed:

The first Victoria Cross ever made – and never awarded; a Crimea War medal: coins of the realm and the plans of the hospital.

The Victoria Cross was slightly tarnished, but otherwise unmarked, said one of the officers who looked at it. Later it was carried, in its box and under escort, to take its place in an exhibition at Aldershot arranged by the Royal Army Medical Corps”.

The chapel had been included in the plans for the overall demolition of the hospital, however as demolition worked along the two wings and started on the central core of the building, a decision was made to retain the chapel, and the tower – for an as yet unknown purpose. As demolition of the Royal Victoria Military Hospital completed, the chapel and tower were all that remained of such a significant Victorian institution that had seen countless thousands of wounded and damaged patients pass through its wards, many of whom would still die of their injuries.

The site now belongs to Hampshire County Council. The grounds occupied by the hospital are now the Royal Victoria Country Park, and after a number of limited uses, and periods of neglect, the council received a National Lottery grant in 2014 to repair and conserve the chapel and tower, and convert into a museum, which opened a couple of years ago.

The museum in the chapel, tells the story of the hospital, medical treatments, and of those who worked and were patients in the hospital. The tower is open to climb to the top where the views provide an appreciation of the size and location of the hospital.

Stairs to the top of the tower:

At the top of the tower, windows provide external views and painted panels give an impression of what the view would have looked like at different periods of the hospital’s history.

Top of the dome, with the original bells in place.

View to the south-east with Southampton Water stretching out to the Solent, the Isle of Wight and the open sea. The wing of the hospital would have originally stretched all the way to the far tree line.

View to the north-west with the buildings of Southampton in the distance. Again, this wing of the hospital would have stretched up to the trees.

Shipping in Southampton is visible from the top of the tower. The Port of Southampton would have been the arrival place for the majority of patients heading to the hospital.

View to the north-east, with the shadow of tower and chapel on the grass.

The tower and chapel of the Royal Victoria Military Hospital. The hospital’s wings would have been dominating the view to left and right.

The hospital sat on flat land at the top of a slope down to Southampton Water. This emphasized the size of the hospital to those passing the hospital on the water.

Historical information about the Royal Victoria Military Hospital has been extended out from the museum in the central chapel, to the surrounding landscape.

In a brilliant example of how this should be done, at the far corners of the original hospital wings, there are corner displays showing the buildings and views from each location.

So from each corner, you can really appreciate the size of the original building.

In the car park are the remains of the rail tracks that once transported patients to the hospital from the docks.

A very different railway runs through the park today:

The museum in the old chapel of the Royal Victoria Military Hospital shows just how a small museum can make use of a building, to display the history of the site, and the people who came into contact with the hospital.

The displays within the landscape of what is now a park, again show how a place that has disappeared can still be represented – it has really been well done.

The Royal Victoria Military Hospital has a fascinating history. After visiting the place, I found the book Spike Island – The Memory of a Military Hospital by Philip Hoare. The book is both a fascinating personal history, and a deeply researched, in depth history of the Royal Victoria Military Hospital.

Out of London, but I am fascinated by history, how places change, and how we can still find the footprints of those places.

Next Sunday, i will be back in London.