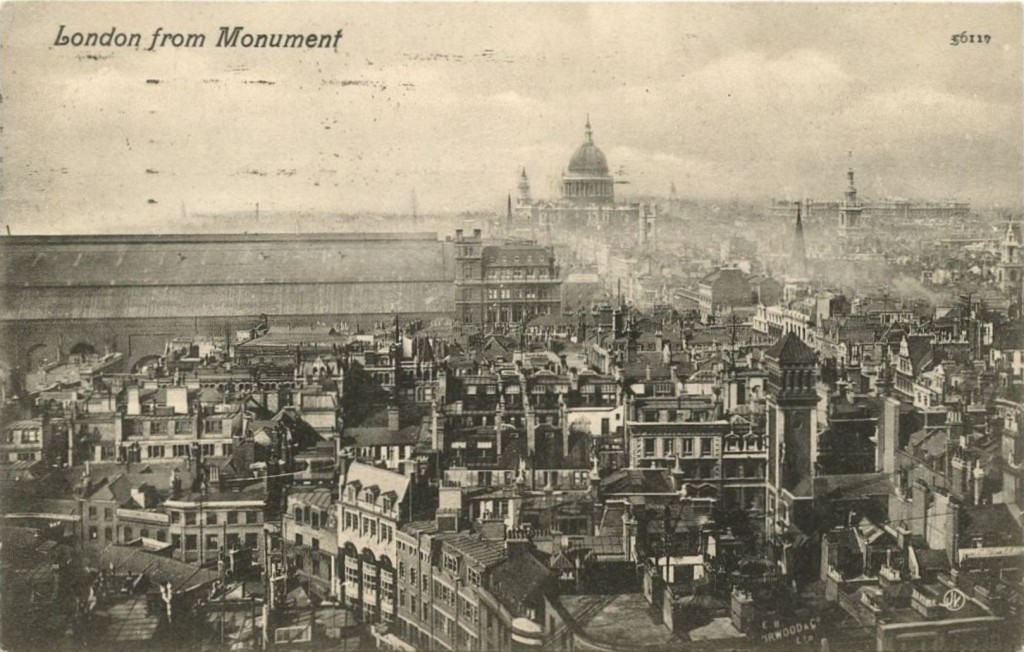

Many of my recent posts have covered sites in London where the view has completely changed, however there are still views in London that have seen very little change over the last 70 years. One such view is looking over the river to Unilever House.

In 1948 my father took the following photo from the southern end of Blackfriars Bridge:

I took the following photo 66 years later standing in exactly the same position:

Very little has changed. The curved building that sits at the north end of the bridge, Unilever House has some cosmetic changes during renovations but is basically the same. Construction of Unilever House was completed in 1933 and since then has been the London head office of Unilever PLC.

Unilever House was built on the site of the De Keyser’s Royal Hotel. This can be seen in the following early photograph that was taken from the opposite side of the bridge to my father’s photo and shows the hotel following the same curved façade to the road as the current building.

De Keyser’s Royal Hotel was opened on the 5th September 1874 by Sir Polydore de Keyser who came to London as a waiter from Belgium and eventually became Lord Mayor of London.

The hotel was very exclusive and initially every guest had to be introduced personally or by letter before they could secure accommodation.

The hotel had 400 rooms and was taken over by the RAF in 1916 and after the war was acquired by Lever Brothers as their London offices. Lever Brothers became Unilever in 1929 when they merged with the Dutch company Margarine Unie.

Also in the above photo, the building at the end of the bridge on the right is Bridge House, which is still standing, but not in use (more of this later).

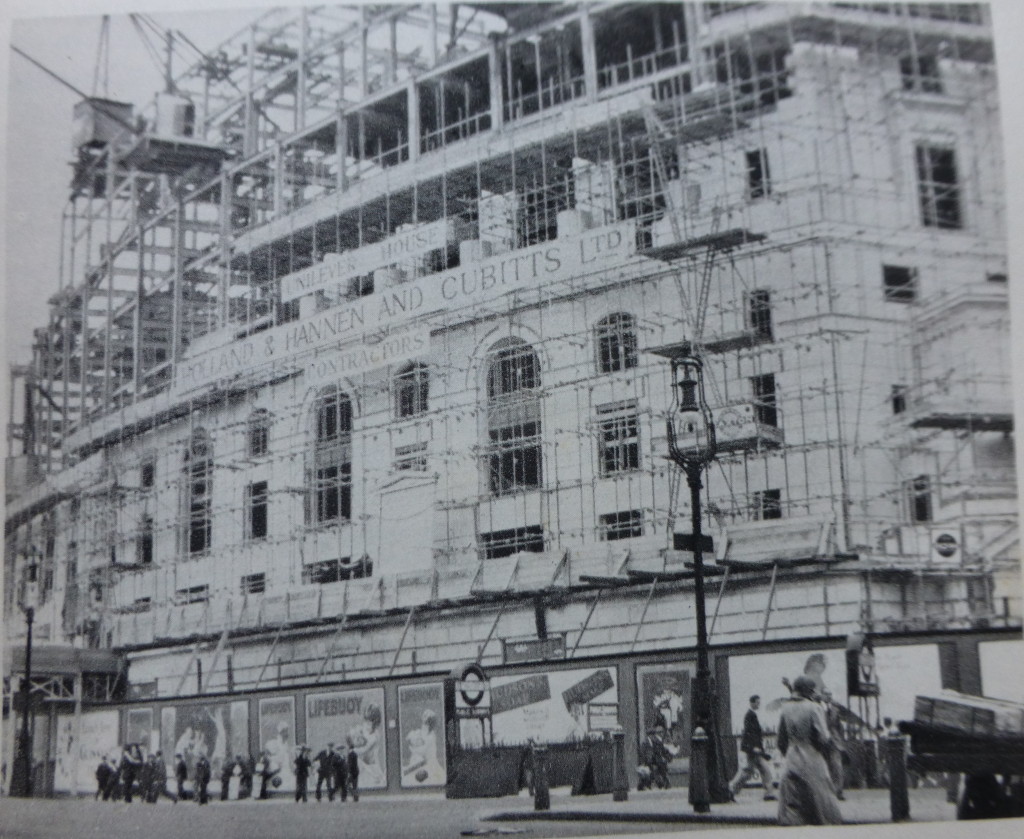

The following photo shows the partly constructed Unilever House on the site of De Keyser’s Royal Hotel:

Note the adverts for Lifebuoy soap on the panels around the base of the construction site, one of Lever’s earliest products.

After taking the new photo to compare the view with my father’s I took a walk across the bridge to the north side. On the north-east side of the bridge, just before reaching the new Blackfriars Station is the now empty Bridge House and tucked in the curve of this building is an old drinking fountain erected by the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association, which now stands rather forlorn in front of Bridge House which from its current state I suspect will soon be demolished, or hopefully renovated.

The Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association was formed in 1859. There is an excellent history of the Association on the site of the Drinking Fountains Association which is well worth reading not just for a history of the association but also for description of Victorian London that supported the formation of the Association.

To quote from the Association’s history:

The supply of drinking water generally available to the poorer classes in London was in those days lamentably deficient both in quantity and quality, coming as it did mainly from pumps and surface wells. A report made in 1866 showed how contaminated this water was, and not only was the impurity of the water held to be largely responsible for the outbreaks of cholera in 1848-49 and again in 1853-54 but the heavy consumption of beer and spirits was in great measure also attributed to this cause. It was therefore high time that something was done to provide a readily available supply of pure drinking water in the cause of temperance, as well as of hygiene and it was to meet this need that the Association came into being.

At the inauguration of the association on the 10th April 1859 the objects of the Association were stated in the resolution:

“That, where the erection of free drinking fountains, yielding pure cold water, would confer a boon on all classes, and especially the poor, an Association be formed for erecting and promoting the erection of such fountains in the Metropolis, to be styled “The Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association“, and that contributions be received for the purposes of the Association. That no fountain be erected or promoted by the Association which shall not be so constructed as to ensure by filters, or other suitable means, the perfect purity and coldness of the water; and that it is desirable the water-rates should be paid by local bodies, the Association only erecting or contributing to the erection, and maintaining the mechanical appliances, of the fountains.”

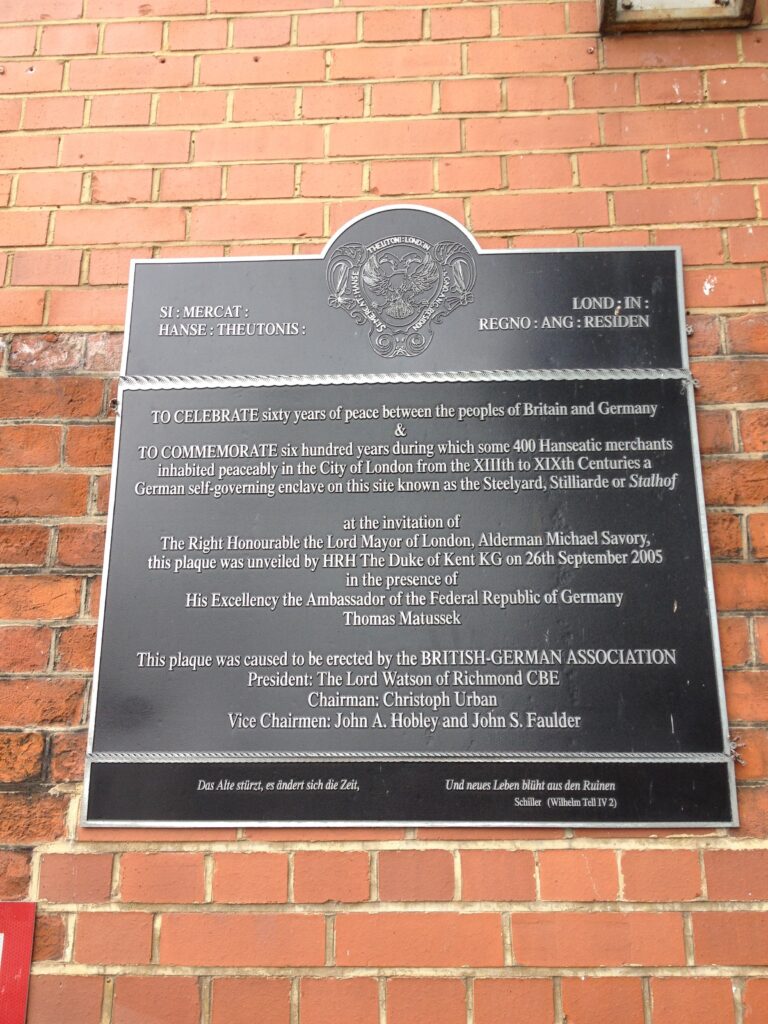

The plaque on the bottom of the Blackfriars drinking fountain states that it was erected by the Association in July 1861 by the Chairman Samuel Gurney MP.

Bridge House with the fountain is shown in the following photo. A telephone box and the fountain, both symbols of earlier ages (with phone boxes I suspect being largely made redundant by mobile phones).

There is much more to say about Blackfriars Bridge which for this post I have only used to cross from the south to the north banks of the Thames, however it has been a busy week so I will leave this for another post to do the bridge justice.

What I hope this post has highlighted is that in almost every corner and building across London there is a fascinating history to be discovered that provides a tangible link back to the lives of Londoners across the centuries.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- The Face of London by Harold Clunn published 1932

- London by George H. Cunningham published 1927

- Old & New London by Edward Walford published 1878

- The Drinking Fountain Association