Thank you so much for ticket purchases of my walks announced last Sunday. They all sold out on the same day. I will be adding a few more dates for these walks in the coming months, and for an update as soon as they are on line, follow me on Evenbrite, here, and I will also announce in the blog.

For today’s post, I am walking along an 18th century engineering and construction innovation that helped transport goods from the counties north of London, into the city, and also served the industry that developed in east London.

The River Lea (Lee is also used, but I will stick with Lea), runs from Bedfordshire, through Hertfordshire, and then through east London to enter the River Thames just to the east of the Isle of Dogs at Bow Creek.

The Lea was used to carry goods, such as grain and malt, from the counties to the north and east of London to the Thames, where barges would turn west and head into the City.

Traffic on the River Lea started to increase considerably during the 18th century, and during this period a number of improvements were made, including locks and cuts, to bypass meanders in the river.

The big problem for those using the Lea to transport goods into the City was the Isle of Dogs. Being to the east, barges and shipping had to navigate around the Isle of Dogs before they could head into the City. This was at a time before the extensive use of steam power and when barges and shipping relied on the wind and tide.

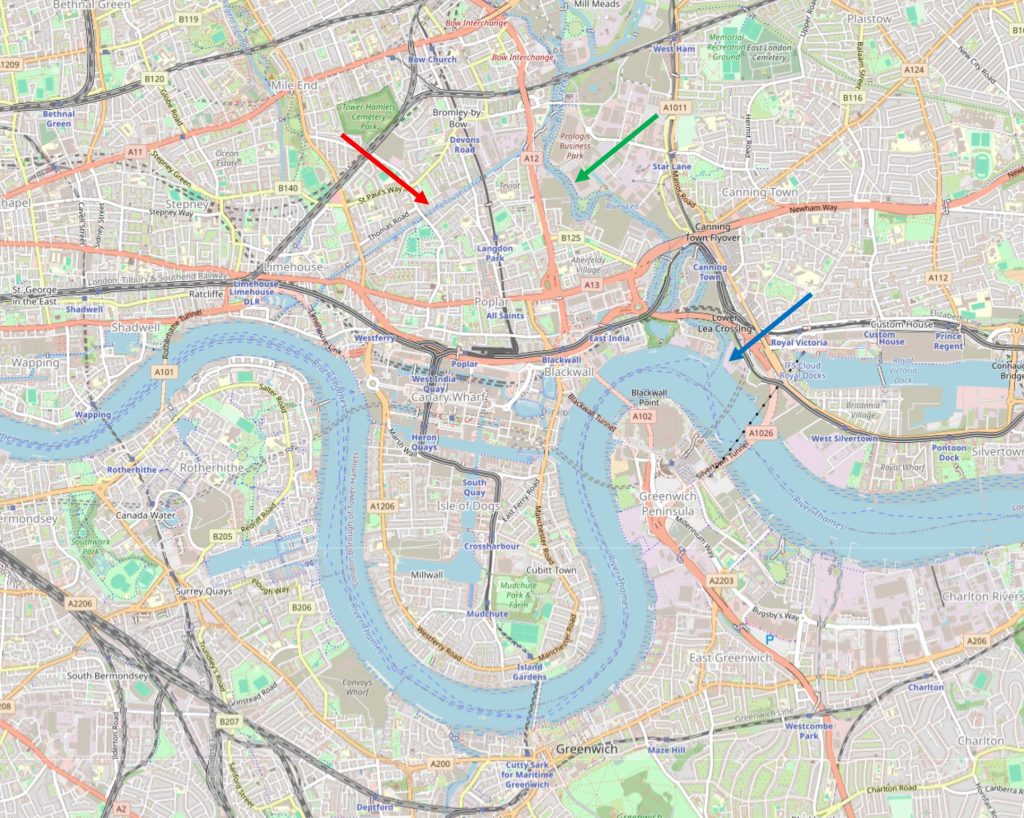

If you look at the following map, the River Lea is highlighted by the green arrow, with the entrance of the river into the Thames shown by the blue arrow. As can be seen, the Isle of Dogs caused a significant addition to the route to head west into the City (map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

There had been proposals to cut a channel through the northern part of the Isle of Dogs to provide a direct route, however use of the land for the docks that expanded across the area was a more profitable and efficient use of the land.

The Civil Engineer John Smeaton had been looking at how the River Lea could be improved to make it easier to navigate, and one of his recommendations was to build a channel or cut from the River Lea to the Thames at Limehouse.

This would provide a direct route to the Thames, and would avoid the time consuming journey around the Isle of Dogs.

The River Lee Act, an Act of Parliament, was obtained in 1766 to build the channel, and work swiftly commenced with the new Limehouse Cut opening on the 17th of September, 1770.

Referring back to the above map, the Limehouse Cut is highlighted by the red arrow, and it can be seen to run from the Lea at the upper part of the Cut, down to enter the Thames at Limehouse.

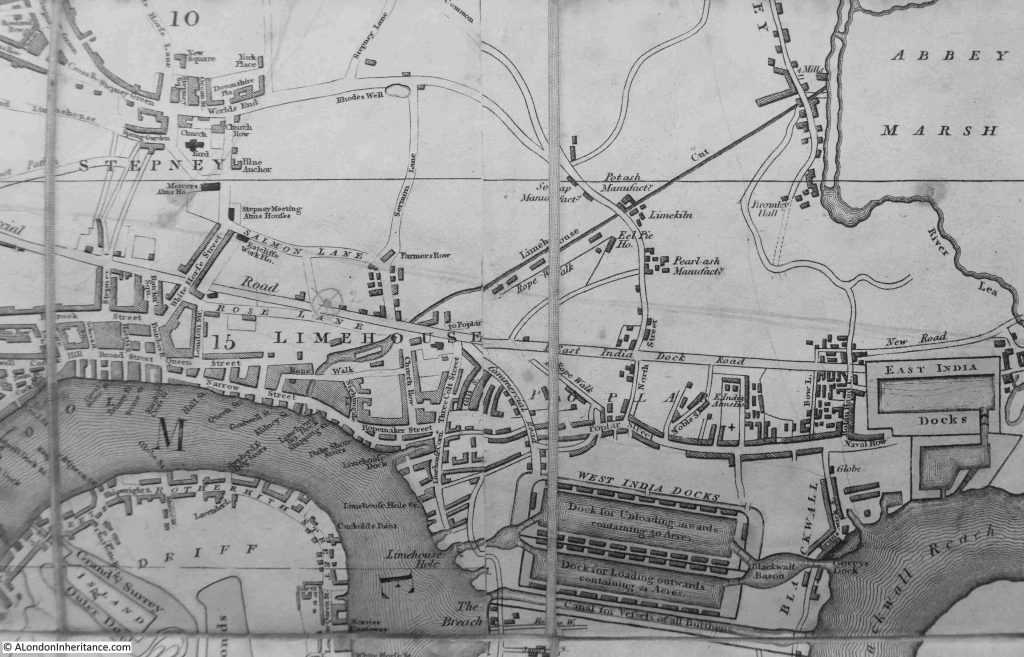

The map today shows the Limehouse Cut running through an area which is heavily built up, however even over 40 years after completion, much of this area was still rural, and in the following extract from the 1816 edition of Smith’s New Plan of London, we can see the Limehouse Cut running from Limehouse up to the River Lea next to Abbey Marsh through mainly empty land, which allowed a very straight channel to be built:

Not that clear in the above map, but the Limehouse Cut ran directly into the Thames, and the original entrance to the river can still be seen today:

The view looking east from where the Limehouse Cut originally entered the Thames, where we see the Thames turning to the right to start its route around the Isle of Dogs:

And looking west in the direction of the City, the Limehouse Cut provided a far more direct route for shipping on the Lea taking their produce and goods to the City:

Whilst the old entrance remains, the Limehouse Cut is now diverted into the Limehouse Basin. If you refer back to the map of the area today, the Limehouse Basin is the area of water just to the left of the lower part of the Limehouse Cut.

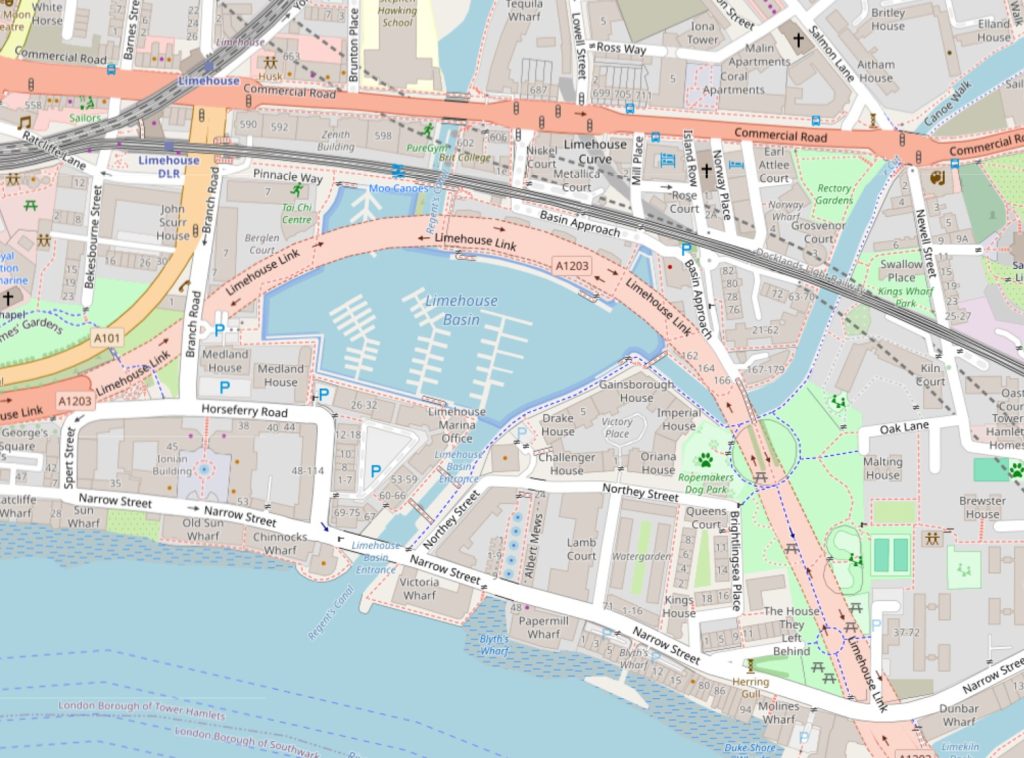

The following map shows Limehouse Basin, look just to the right of where the channel from the basin enters the Thames and there is an indent. This is the original entrance to the Limehouse Cut (map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

The Limehouse Basin, or originally the Regent’s Canal Dock opened along with the Regent’s Canal in 1820, to form a place where shipping could dock, load and unload whilst transferring their goods between the barges that travelled along the Regent’s Canal.

The two entrances to the river for the Regent’s Canal Dock and the Limehouse Cut were very close together, and for eleven years between 1853 and 1864, the Limehouse Cut was diverted into the Regent’s Canal Dock, however after 1864 the original entrance was back in use, with a new bridge carrying Narrow Street over the canal. It seems that the return to the original route into the Thames was down to the imposition of additional charges and rules by the owners of the Regent’s Canal Dock on the users of the Limehouse Cut, who now had to pass through the dock to reach the Thames.

Use of the original route would last for another 100 years, when the Limehouse Cut was rediverted back into what is now Limehouse Basin, a routing it retains today.

Although blocked up where the original entrance meets Narrow Street, we can follow the old route of the Limehouse Cut in the way the area has been landscaped as part of the redevelopment.

The side of the 1864 bridge that once carried Narrow Street over the Limehouse Cut remains:

The following photo is the view looking north from the bridge which once took Narrow Street over the Limehouse Cut, and a channel of water follows the original route. It was here that a lock was located to control the height and flow of water between the tidal Thames and the Limehouse Cut:

Which then continues after Northey Street:

And in the following photo, I am now at the Limehouse Cut, where it curves to head towards Limehouse Marina. The original route to the Cut is to the left of the photo:

The following photo is looking north along the Limehouse Cut at the start of the walk. The first of many bridges can be seen. This one carrying the DLR over the Cut:

The Limehouse Cut took just 16 months to build, and was the first canal built in London as well as being one of the first across the country.

As can be seen in the maps at the start of the post, the Cut was (and still is) remarkably straight, and it followed a minor geological feature, where there was a slightly higher flood plain to the north west, and slightly lower flood plain to the south east of the Cut, although with so much later construction, this feature is hardly visible today.

The first road bridge we come to is the bridge that carries the Commercial Road over the Cut:

The Commercial Road was built in the first years of the 19th century to connect the expanding docks to the east of the City, with warehouses, business premises and workers in the City and east London.

The Evening Mail on the 24th of August, 1804 was reporting on the build of the Commercial Road (or Grand Commercial Road as it was first called), and highlighted the Limehouse Cut as being one of the obstructions in Limehouse: “At a short distance before it arrives at Limehouse church, the direct communication is impeded; but to prevent, as much as public convenience could admit, any variation, the bridge of the Limehouse Cut is considerably enlarged”.

Although the bridge was enlarged, the Limehouse Cut still narrows as it passes under the bridge.

Along the route there are reminders of the heritage of the Cut, with features once used for mooring ropes:

Passing under the Commercial Road Bridge, and this is the view looking north:

Much of the Limehouse Cut as well as the Limehouse Basin was covered in green weed growth, possibly a result of the hot summer:

The majority of the land along the side of the Limehouse Cut has been converted to either new apartment buildings, or renovation of earlier buildings into apartments.

Very little examples of the old industries that once lined the Limehouse Cut remain, in the following photo is an example of part of the industrial heritage of the area:

In the late 19th century, the space in the above photo was occupied by a disinfectant factory. I do not know if the buildings and chimney we see today are part of that business, or from the early 20th century.

I have been trying to build a list of all the businesses that once operated along the Limehouse Cut, but it is one of many projects that is taking time to complete and is only partly done.

Looking to the right of the above photo, and we see the bridge carrying Burdett Road over the Cut. A Lidl is on the left, on space once occupied by a lead works:

Passing under the Burdett Road bridge, and the Limehouse Cut carries on to the north. Walking the Cut highlights just how straight the route taken for the construction was, although the empty fields on either side have long gone.

To walk the Limehouse Cut, the eastern side of the Cut is the best route to take, this provides a continuous walkway from the Limehouse Basin, all the way up to where the Cut joins the River Lea.

The eastern side is marked “towing path” on OS maps, so this was the continuous pathway alongside of the Cut so horses and men could pull barges along the length of the Cut.

It is possible to walk parts of the western side of the Cut, however much of this route is built up to the edge of the water.

Along the footpath, there are more reminders of the heritage of the Cut:

Somewhere to stand and look out over the Cut:

Walking further along the Limehouse Cut, and there is a bit more industry along the western edge. Not the dirty, manufacturing businesses that once occupied the space rather light industrial, storage and distribution etc.

A short distance along and there is a short indent to the Cut named Abbott’s Wharf:

There was an Abbott’s Wharf to the left, however checking the OS maps for 1914 and 1951, and there is no indent at this position. There was an Abbott’s Wharf as a set of large buildings to the left, but the OS maps show a continuous tow path, without any indent, so this is probably part of the recent redevelopment of the area as a new apartment block to the right of the wharf is named Abbott’s Wharf.

A short distance along is the bridge that carries Bow Common Lane (to the west) and Upper North Street (to the east), across the Limehouse Cut:

The Limehouse Cut, along with the Regent’s Canal, helped the considerable industrial development of the area, and industry took up a considerable length of the sides of the Limehouse Cut.

Much of this was dirty, polluting industry, although there were places such as biscuit factories along the route.

In the 1860s, the rector of St. Anne’s Limehouse wrote that “no bargee who fell in had any chance of surviving his ducking in the filthy water”, such was the polluted state of the water.

Despite this claim in the 1860s, and the considerable range of dirty and polluting industries alongside the Cut, in 1877 the Limehouse Board of Works was claiming that the water was in excellent condition. At a meeting looking into a number of local issues, when talking about fever and smallpox:

“Mr. Peachey stated that fever was prevalent in the neighbourhood of the Limehouse Cut. Mr. Potto said that the disease could not be attributed to the Limehouse Cut for the water there was in excellent condition.”

I am not sure though whether Mr. Potto would have been happy to swim in the Cut despite his claim.

The bridge shown in the above photo was a notorious place for the appalling smell from adjacent industries and the bridge acquired the name of Stinkhouse bridge.

Stinkhouse Bridge was mentioned in numerous newspaper reports in the 19th century, including one report in 1844 about a fire at a factory complex next to the bridge. The factory was a pitch, tar and naphtha distillery. Naphtha is a distillation of crude oil, gas, or coal-tar.

There were attempts at cleaning up the root cause of the smells, for example, the following is from the East London Observer in November 1878, reporting on a local council meeting, where:

“The Medical Officer of the North District (Mr. Talbot), reported that in consequence of complaints made to him concerning noxious vapours in the vicinity of ‘Stink House Bridge’, he had carried out a series of systematic observations both as to their existence and their causes. The results of his examination, with the assistance of Inspector Raymond, were that the nuisance was traced to some six factories, and in each case a notice had been served by order of the Sanitary Committee, and a communication sent to the Metropolitan Board about the discharge of ammoniacal liquor into the sewers.”

The notices served do not seem to have had too much impact, as complaints continued for many years.

The name Stinkhouse Bridge continued to be in use for many decades. The last written use in either local or national press was in 1950.

Underneath the bridge, there are raised sets along the towpath. I do not know if they are original, or if they were there to help provide grip for the horses pulling barges along the Cut:

As with the River Thames, the Limehouse Cut was both a playground and a death trap for children.

As industry populated the banks of the Cut, and streets with housing covered the surrounding area, children were drawn to the Cut by the attraction of water, the novelty of the barges both moored and passing along the Cut, and the variety of places to play.

This resulted in the deaths, usually by drowning, of a considerable number of children. Looking through old newspapers, a child’s death is reported almost every year.

For example, two years that are typical:

- 1936 – A verdict of accidental death was recorded by Dr. R.L. Guthrie at a Shoreditch inquest upon John Brown aged 7, of 72 Coventry Cross Estate, Bow, who was drowned in Limehouse Cut on Saturday

- 1937 – Dinner Hour Swim which Ended Fatally. A verdict of accidental death was recorded on George Henry Hector, aged 16, employed at Crown Wharf, Thames Street, Limehouse, who was drowned in Limehouse Cut

Fires were frequent along the Limehouse Cut, both in the buildings alongside, and in the barges travelling and moored along the Cut. Buildings were often storing or processing, and barges were transporting, highly inflammable goods.

One such example is from 1935, as reported in the following article;

“Frederick Carpenter, aged 15, of Provident Buildings, Limehouse, played a valuable part in assisting to prevent the spread of an outbreak of fire which involved three barges lying in Limehouse Cut, near Burdett Road, Limehouse.

Several craft were stationed close together, and Carpenter leapt through flames and smoke to loosen moorings so that those which were on fire might be separated from the rest. A crowd on onlookers helped to drag other barges out of the danger area. Of the barges which caught fire two were laden with timber and one with bales of sacks.

Firemen fought for more that an hour to extinguish the blaze.”

The Limehouse Cut is a very different place today:

In the above photo, the Limehouse Cut appears reasonably wide. It does narrow where it passes under bridges, but for much of its length, it is wide enough for barges to be moored either side, and a couple of barges to pass in the centre. This was not how the Cut was originally built.

When the Limehouse Cut was opened in 1770, it was only wide enough to carry a Lea Barge with a standard beam (width) of 13 foot. Very quickly this became a significant problem with the number of barges attempting to travel both ways along the Cut.

A couple of years after opening, passing places started to be built along the length of the Cut, but this was a very limited solution, and to support the expected rapid increase in use of the Cut, in 1773 it was decided that the whole length of the Cut should be widened to allow barges to pass in both direction.

It took some time to widen a working canal, but by 1807 the majority of the Limehouse Cut had been widened to 55 feet. The challenge was with the bridges, and as can still be seen today at a couple of the bridges, the Cut narrows to pass underneath the bridge.

The Limehouse Cut continues to be lined with a much smaller number of barges than when the Cut was in use as a route between the River Lea and the Thames, and the majority today appear to be residential:

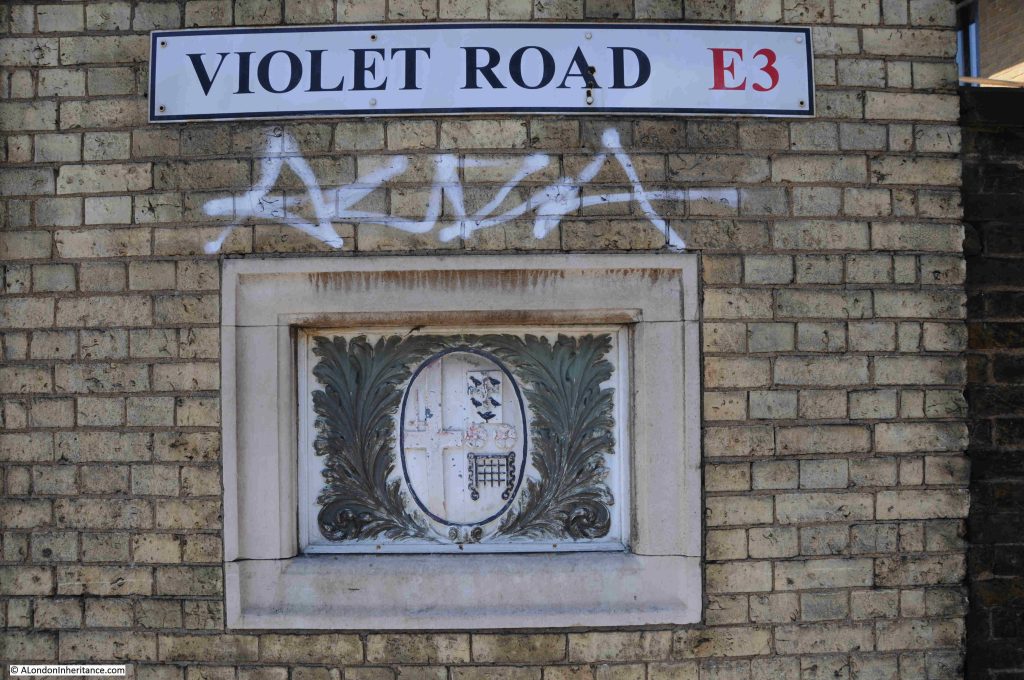

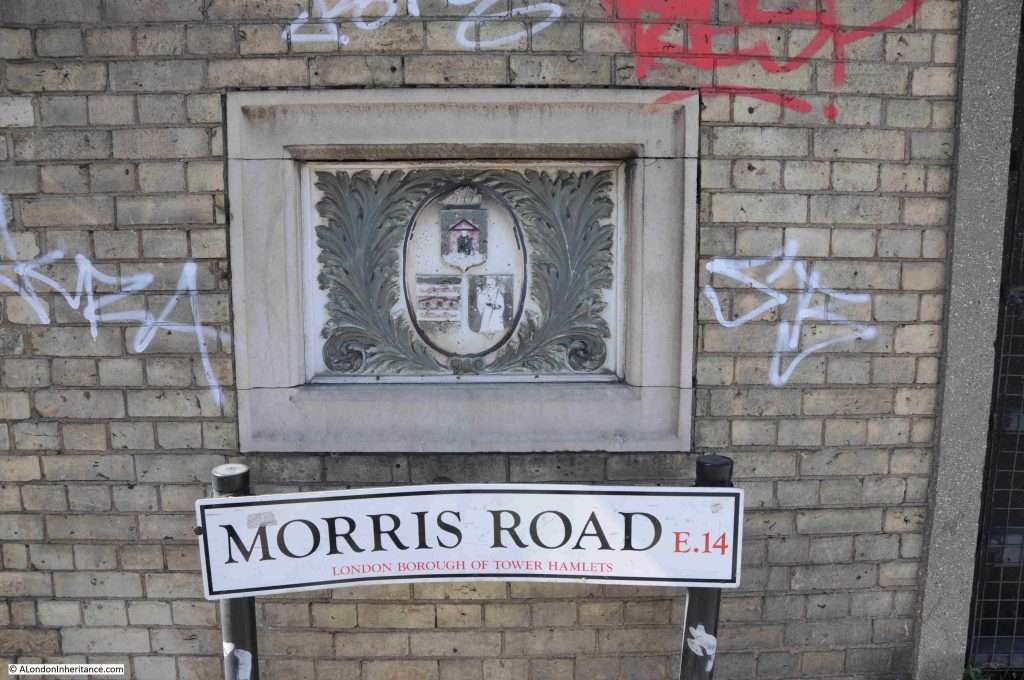

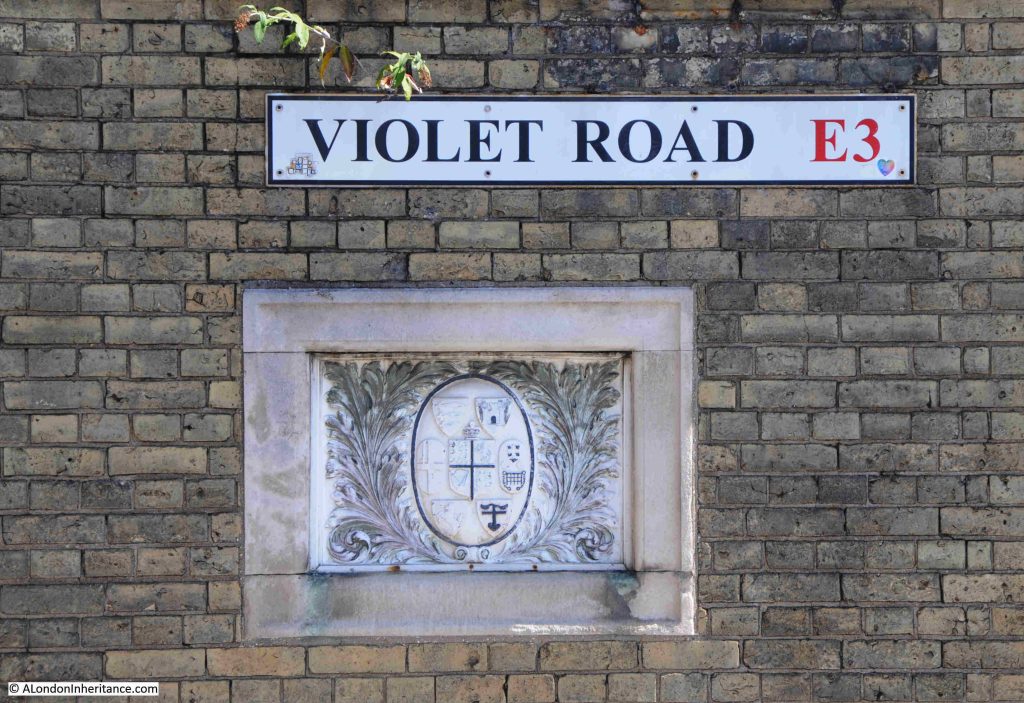

The following bridge carries Morris Road (to the south east) and Violet Road (to the north west), over the Limehouse Cut:

There are a range of interesting features here, and it is worth walking up to the bridge to take a look.

Firstly, along the eastern side of the Limehouse Cut is Spratt’s Patent Limited factory, a manufacturer of foods for a wide range of domestic animals, probably best known for their dog foods:

In 1910, Pratt’s Patent were supporting the Cruft’s dog shows, where they were described as “the universal providers to the dog, poultry and caged bird fraternities”.

At a 1910 Kennel Club show at Crystal Palace, Spratt’s Patent provided the food for 3,346 dogs.

Spratt’s Patent was founded by James Spratt, an American electrician who arrived in the UK in the 1850s intending to manufacture and sell lightning conductors.

The story behind the animal foods business is that in east London he saw dogs eating the hard biscuits left from the ships docked in the area. He patented a new dog food which was made by baking wheat-meal which had been mixed with rendered meat and vegetables.

Whether it was coincidence or not, Charles Cruft, the founder of Cruft’s Dog Shows started off as an employee of Spratt’s Patent, and when Cruft went on to run the dog shows, Spratt’s became a key supplier.

For many years, the company was the largest manufacturer of dog food and dog biscuits in the world, and supplied not just domestic demand, but also the US and Europe, along with exports to many other countries.

They also had premises in Bermondsey and Barking. Their address in Bermondsey was used for advertising featuring Dog Medicines, Poultry Houses, Appliances and Medicines, and via Bermondsey, dog owners could also entrust Spratt’s Patent with their dogs whilst they were on holiday. The dogs were transferred to Mitcham, as in the following from the Kilburn Times in July 1891:

“PETS IN HOLIDAY TIME – our readers, before leaving for their holidays , might entrust their canine friends as boarders to Spratt’s Patent Dog Sanitorium, which is on a healthy site near Mitcham. The kennels are large and spacious, the dogs are groomed and exercised for several hours daily, and are not caged or chained. Write Spratt’s Patent Limited, Bermondsey for all particulars.”

Today the building is mainly residential.

The bridge carrying Morris and Violet Roads over the Limehouse Cut has a new deck, however at the four corners of the bridge, the brick pillars survive:

On one pillar is a plaque that tells that the bridge was built by the Board of Works for the Poplar District, and that it was opened on the 19th of May, 1890.

On the other three pillars there are coats of arms. These seem to be arms of many of the boroughs in London that may have some involvement with the Limehouse Cut.

In the following, the arms of the City of London are on the left, not sure about the arms on the right:

Morris Road is the eastern side of the bridge, towards Poplar, and the arms on this side of the bridge are those of old Poplar Borough Council:

And the third pillar has a collection of arms, which I need to research:

Back down alongside the Limehouse Cut, and the banks along the western side look almost as if they are lining a country canal.

In the next post, I will complete the walk, and reach where the Limehouse Cut meets the River Lea, the Bow Locks, and take a quick look at the Bromley by Bow Gas Works and Three Mills Island.

Lovely photos of a beautiful part of London.

I looked into the growth – possibly duckweed? Seems to be an issue in London canals after heatwaves.

https://web.archive.org/web/20231014162521/https://canalrivertrust.org.uk/media/original/33309-hot-weather-causes-green-carpet-of-duck-weed-on-londons-canals.pdf

I was so disappointed that all I missed out on your recent walks, but great for you that they sold out the same day. Let’s hope I can get a ticket for future walks. I’ve just read ‘Walking the Limehouse Cut – Part 1’, and am looking forward to Part 2. It’s so well researched, clearly explained and interesting (I walked part of the River Lea on Friday) and your photographs are superb. However, please add full stops before However, so that it starts a new sentence.

to provide a direct route, however use of the land

which is heavily built up, however even over 40 years

Regent’s Canal Dock, however after 1864 the

side of the Cut, however much of this route

Abbott’s Wharf to the left, however checking the OS maps

Limehouse Cut has a new deck, however at the four corners

Very best wishes

Susie

A very enjoyable read

Thank you

John Smeaton (1724-1792) designed the third Eddystone Lighthouse established in 1759, now on Plymouth Hoe,

He pioneered use of mortar which would set under water, coined the term civil engineer (as opposed to military engineer) and formed a society which became the Institution of Civil Engineers.

He is commemorated in Westminster Abbey.

In the 1980s I used to work in a studio in the Pratts dog biscuit factory. It had recently been developed by my bosses husband. We were a studio doing textile conservation. Many of the apartments were bought by artists. I used to hate walking down Morris Road particularly in the dark after work. It seemed soulless. Opposite was a bottle recycling company which was very noisy.

Really enjoyed this as all my paternal ancestors lived and/or worked in Limehouse at some point. Looking forward to part 2!

I suppose Spratts set up premises in Barking because there was no room on the Isle of Dogs.

Great read and photos, thank you.

Residing in “landlocked” Munich, I thoroughly enjoyed once more this fascinating post.

Looking forward to part 2, too.

Thank you,

Günther K.

A very good read. It is not coincidence at all that Crufts was started by an employee of Spratt’s, it’s original purpose was to advertise and sell their products. Dog shows are still largely sponsored by food manufacturers to this day.