There are just three tickets left for my Southbank walk in July. The Barbican walk has now sold out. Click on the link for details and booking:

The following photo is of a rather strange feature on the top of a building looking towards King’s Cross Station. The photo is one of my father’s from 40 years ago in 1984:

I was in the King’s Cross area last week, it was a sunny day, and the sun was in the right position, so I took the following photo showing the same feature as it appears today, along with a view of the building below:

The shape of the building is down to the convergence of the roads on either side, with Pentonville Road on the left and Gray’s Inn Road on the right.

The building is now called the Lighthouse Building, after one of the possible uses of the structure on the roof. The building is Grade II listed, and the Historic England listing includes the following description:

“Above the 3rd floor windows a further cornice and blocking course, surmounted at the apex by a tall lead-sheathed tower, sometimes said to have been for spotting fires, with a cast-iron balcony at half-height, oculus and cornice capped by a small ribbed dome with weathervane finial.”

The listing suggests that the tower was used as a lookout for spotting fires.

Another frequently reported use for the tower was as a lighthouse, and was down to an oyster bar which occupied part of the ground floor of the building. This was “Netten’s Oyster Bar”, and the story goes that when fresh oysters were available in the shop, the light would go on in the “lighthouse”.

I have no idea whether this story is true, or whether the use of the tower for spotting fires is true, of whether it had a different purpose, or was just an ornamental folly.

I found plenty of adverts for Netten’s oyster bar, and the lighthouse was not mentioned in any of these. Netten’s would advertise in the local newspapers of towns where their local station provided a route into King’s Cross or St. Pancras Stations. For example, the following appeared in the Luton Reporter:

“Luton Travelers To London, Should Dine, Lunch, or take Supper at J. Netten’s Fish Restaurant & Oyster Bar, 297, Pentonville Road – King’s Cross.

Boiled or Fried Fish of all kinds in season, fresh cooked for each customer.

Native Oysters 1/- 1/6 & 2/- per dos. Tripe and Onions and Stewed Eels Always Ready”

Rather than native oysters, boiled or fried fish, the traveler arriving in London from Luton today, would find a Five Guys, burger and fries restaurant in the place of Netten’s Fish Restaurant & oyster Bar, so whilst the foods on offer have changed, the need for travelers to buy some food during their journey has not.

The building was completely refurbished in a project that completed around 2013, and this work included the tower on the roof. In previous years the interior had been derelict for some considerable time, and the tower had been a magnet for graffiti. It had been on Historic England’s Buildings at Risk Register, so the refurbishment possibly saved the building. It had been at risk from demolition in previous years from plans to extend the eastern entrances to King’s Cross underground station.

If you go back to my father’s 1980’s photo, you can see that some of the railings around the tower were missing.

In 2016, I was in the clock tower at St. Pancras Station and took the following photo of the area in front of King’s Cross Station (on the left) and the refurbished Lighthouse Building can be seen looking across to the station:

And this is the view from ground level today. A very busy place with plenty of travelers heading to and from the stations of King’s Cross and St. Pancras:

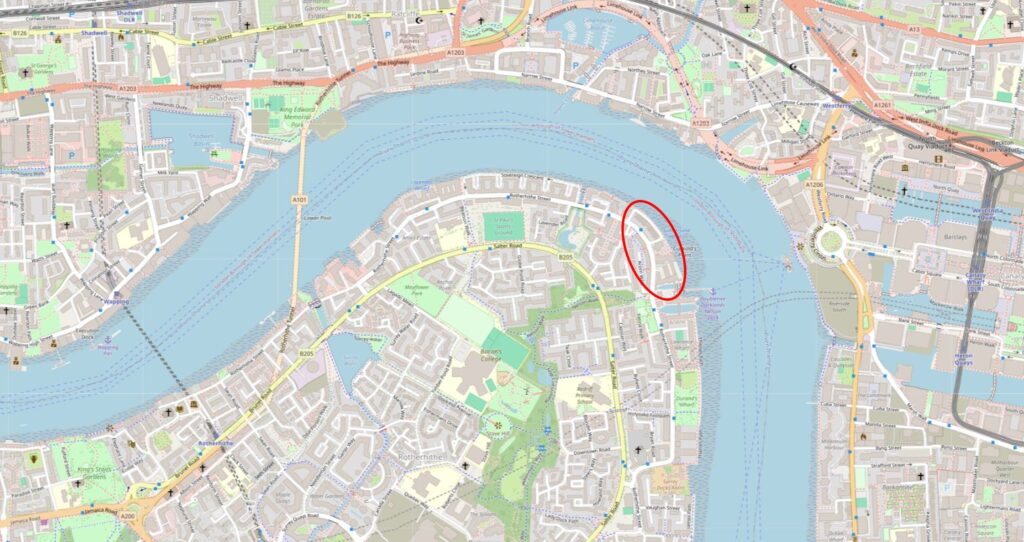

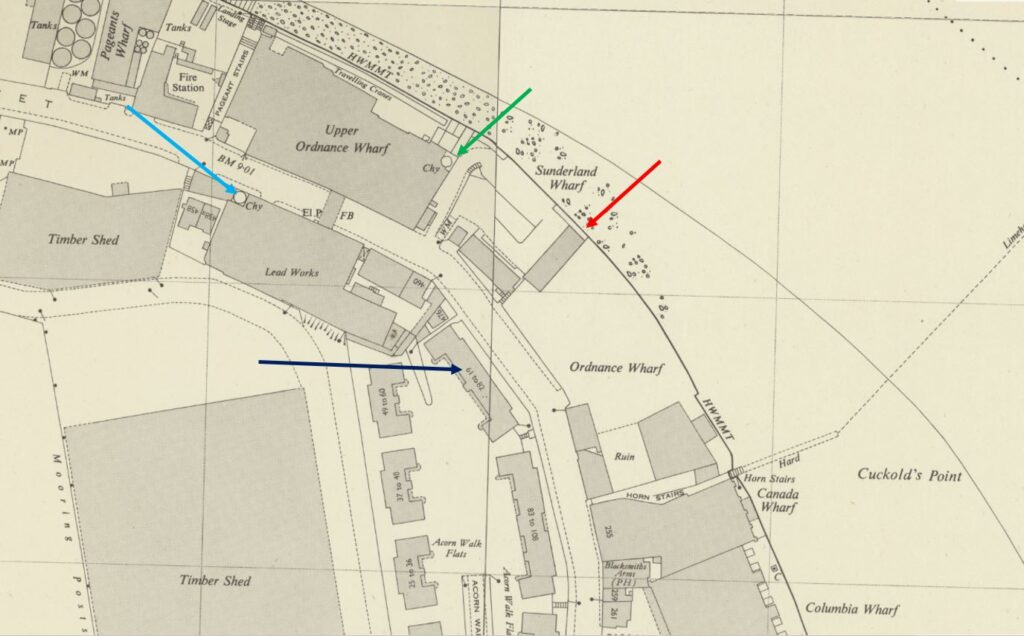

The metal tower, or lighthouse is not the first landmark structure that has been where Pentonville Road and Gray’s Inn Road meet. Before King’s Cross Station was built, there was a structure that would go on to give both the station, and the local area, the name King’s Cross:

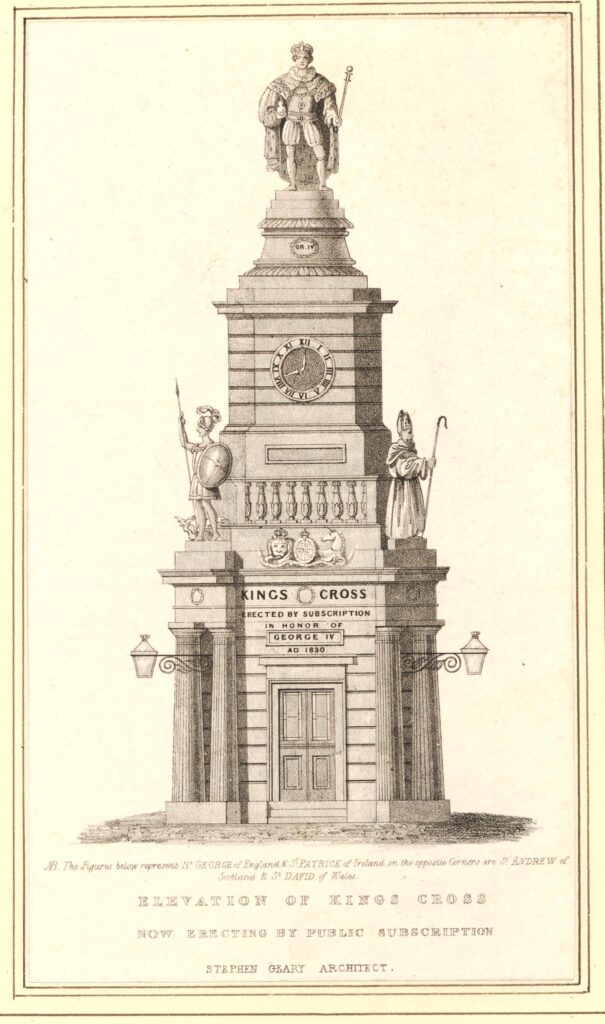

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

On the 26th of June, 1830, King George IV died, and in the year before his death, a monument had been proposed, design and construction had started, to commemorate the reign of the king.

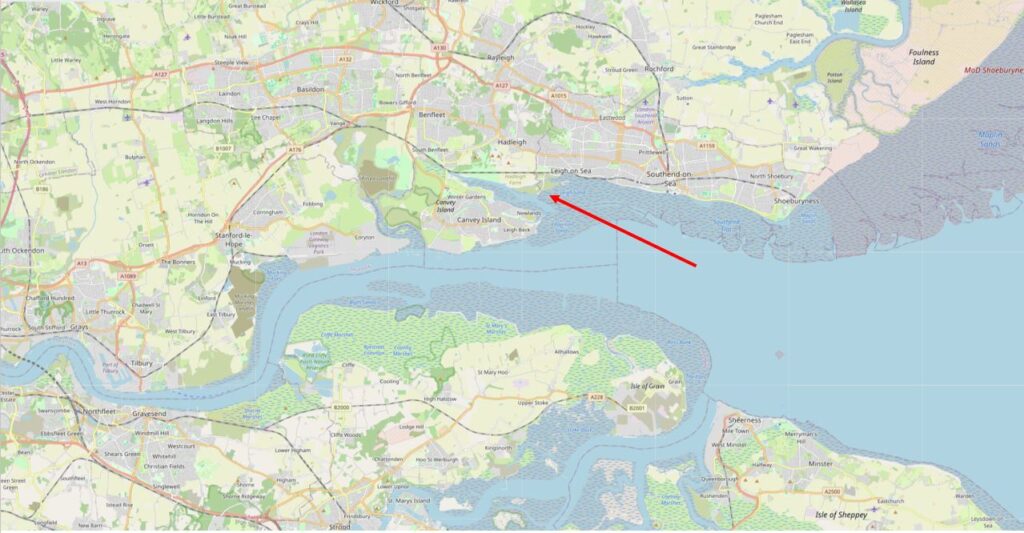

The site chosen was at the junction of what is now Gray’s inn Road, Euston Road, and Pentonville Road as from the late 18th century into the 19th century, this area was developing rapidly (even before the arrival of the railways), and the New Road (which would become Euston and Pentonville Roads) had been built as perhaps the first North Circular Road around London to divert traffic away from the centre, to provide a new east – west route, and to take traffic to and from the expanding docks to the east of London.

The print above shows an “Elevation of Kings Cross” as it was intended to appear when completed.

As recorded on the above print, money for the design and build of the monument was being sourced from public subscriptions, however even with building underway, there were not enough funds being received, as recorded in the following article from the London Star on the 2nd of July 1830:

“Whatever may tend towards the recollection of the revered departed monarch will doubtless be received with that degree of loyal feeling which is so characteristic of the true Englishmen.

The splendid National Monument of the King’s Cross (commenced in February last by a few loyal though humble individuals) to commemorate the reign of George the Fourth, approaches now rapidly to completion, and will be finished according to the design of Mr. Stephen Geary, architect. We hesitate not to say it will form one of the most splendid and ornamental objects that adorn the environs of the metropolis, combining not only simplicity of design, but chastity of Grecian architecture.

The Colossal Statue of his late Majesty, surrounded with the emblematical representatives of the Empire, vis. – St. George, St. Andrew, St. Patrick and St. David, will form additions to the various productions of that eminent artist and sculptor, R.W. Seivler, Esq. who is now busily employed upon them.

Although credibly informed, we can scarcely believe the amount of subscriptions received to this public monument are very far from meeting the amount already expended.

Surely a public appeal need only be made, and we doubt whether there is an Englishman, Irishman, Scotchman, or Welshman, who possesses a spark of British loyalty in his breast, who will not subscribe his mite towards handing down to posterity a public token of attachment towards the departed and beloved Monarch, George the Fourth.”

Financial troubles continued, and in 1832 the Kings Cross monument was put up for auction, with the outcome of the auction reported as follows:

“Thursday afternoon, at the Mart, was sold the ornamental, stone-built erection at the junction of the Pentonville, New, Gray’s Inn-lane and Hampstead Roads, partly built by subscription, and intended to receive on its summit an equestrian statue of George the Fourth.

The auction caused a numerous assemblage, and gave rise to much discussion, and it was objected that there was no title, and that the subscribers had a claim upon it, as well as the assignees of the party who had completed it and under whose direction it was being sold. It was further said it might be removed, being built in contravention of the local Paving Act.

The auctioneer admitted that the only title was the written consent of the Commissioners of Roads, and the approval of the Paris Vestry; but it was not liable to any objection as to the local Act, nor was it likely to be pulled down, as it was of great benefit to the public, protecting passengers in the day and serving as a beacon at night.

It was also a great ornament to the district, and had cost nearly £1,000. It was at present let to the Commissioners of Police at £25 a year. the biddings then commenced, and the King’s Cross was knocked down, and bona fide sold for 164 guineas only.”

The only value in the monument seems to have been the small building that formed the base which, as the above article records, was let to the Police, and was generating an income. in the following years it would also become a shop, and finally a pub / bar.

In the years after construction, there also seems to have been a campaign to downgrade the public perception of the quality of the monument, and the statue of King George IV. Newspaper reports tell of cabmen, watermen, and the general public complaining about the statue, and as traffic on the New Road (Euston and Pentonville Roads) increased, the monument was also becoming an obstruction.

In 1841 there was a letter to the editor of the Globe complaining of the dangers of the monument, and that it did not have any surrounding posts or rails to protect pedestrians, and was also unlit at night.

The days of the monument were numbered and in 1842 the statue of the King was removed, and soon after, the whole monument was demolished. Not exactly “handing down to posterity a public token of attachment towards the departed and beloved Monarch, George the Fourth” as suggested in the appeal for public funds a few years earlier.

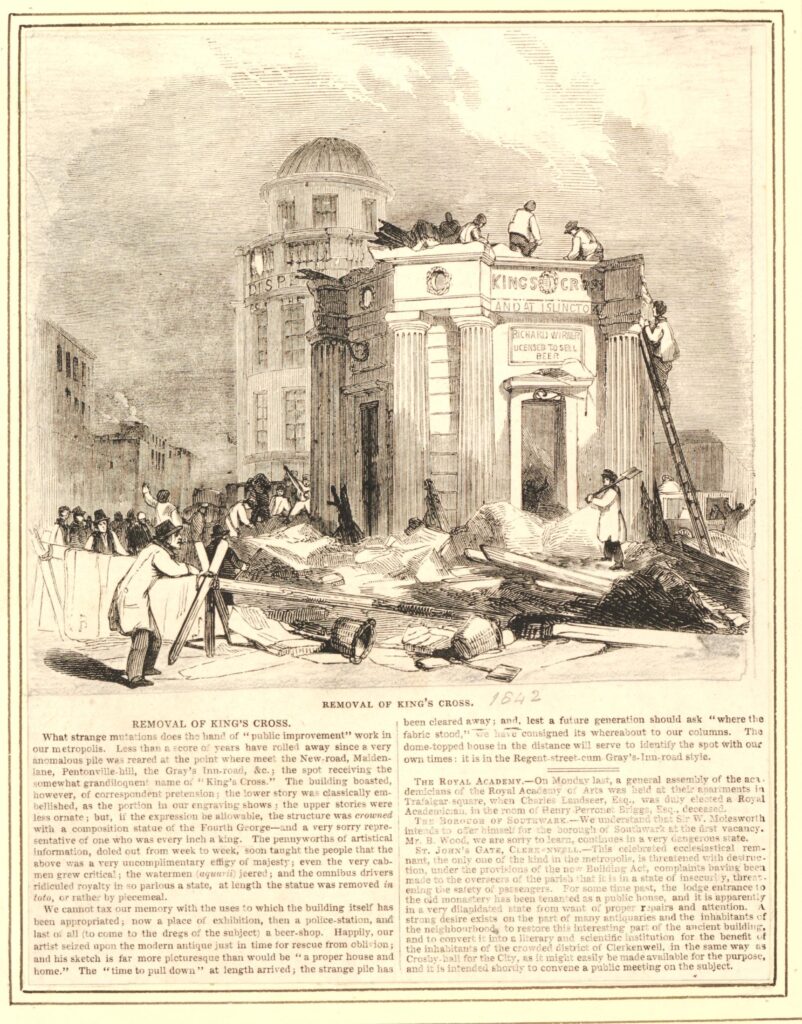

The following print shows the demolition of the monument:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Above the entrance to the room at the base of the monument can be seen the words: “Richard Wirner Licensed To Sell Beer” – the monuments final use.

The text below states that “the dome-topped house in the distance will serve to identify the spot with our own times”, however this building would also soon be disappearing as the area would be part of the construction site for a major transport project. Not King’s Cross or St. Pancras Stations, but the Metropolitan Railway.

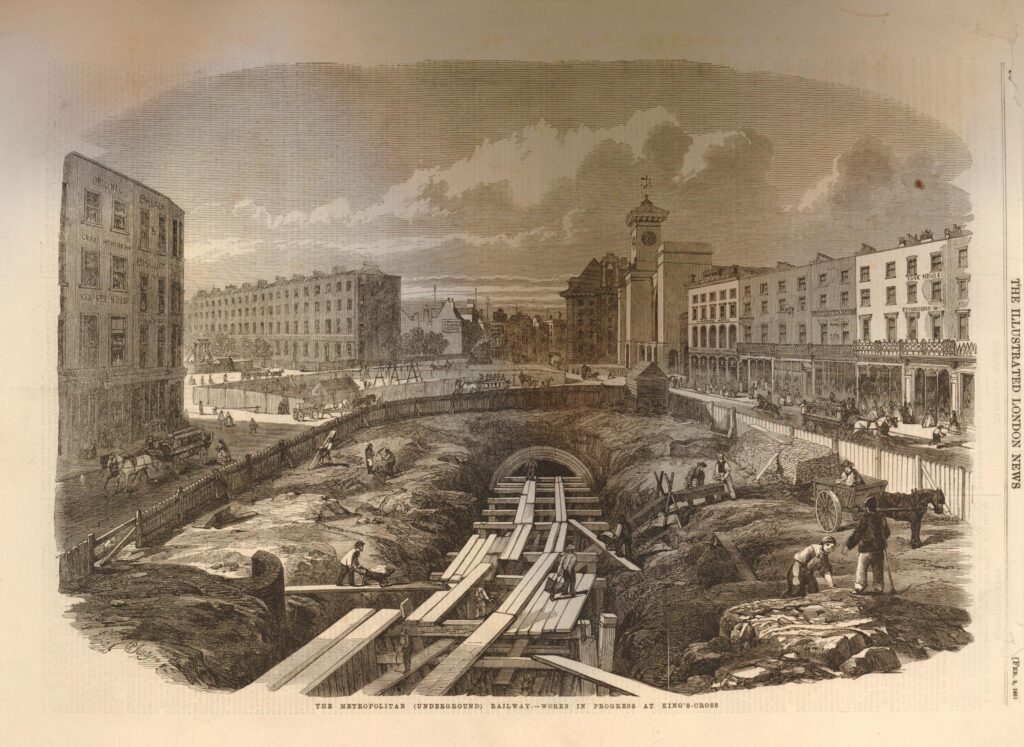

The following print shows the cut and cover construction of the Metropolitan Railway, which ran through the site of the George IV monument, and the building that was on the site of the Lighthouse building:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The building with the tower / lighthouse on the top was then built on the site in around 1875.

I cannot find a confirmed date for the tower / lighthouse, whether it was part of the original 1875 building, or whether it was added later.

A rather strange story, that a monument that could not raise enough public funds to complete the build, does not appear to have been appreciated by the public, and only lasted for just over 10 years before demolition, gave its name to the area, and to one of London’s major railway stations.

An almost throw away comment in the Lincolnshire Chronicle on the 14th of November, 1845, in an article where the paper reported on the introduction to Parliament of the London and York Railway Bill hints at what would become a nationally recognisable name: “And the said Bill proposes to enact, That the said Railway shall commence in the Parish of St. Pancras in the County of Middlesex at or near a certain place called King’s Cross”.

The tower / lighthouse that overlooks the site of the monument to George IV has lasted much longer, and after restoration, should be there for many more years to come.