Tindals Burying Ground was the original name of the Bunhill Fields Burial Ground, which today can be found between City Road and Bunhill Row.

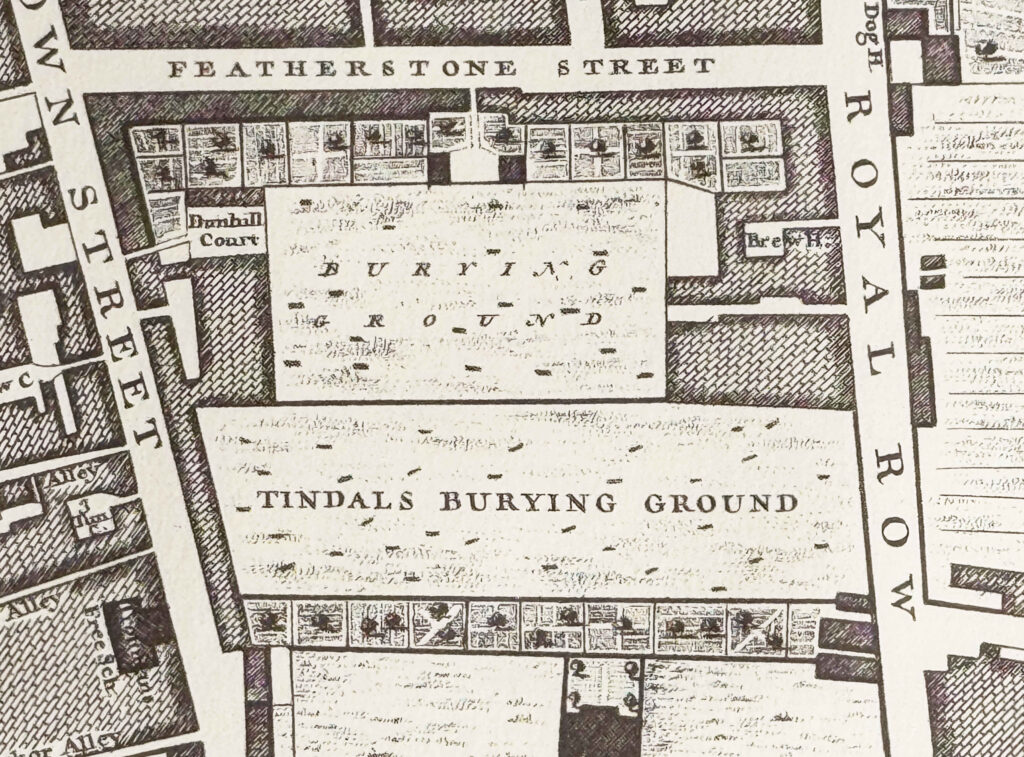

The following extract from Rocque’s 1746 map of London shows Tindals Burying Ground:

The original name of the burying ground follows the setting aside of an area of land as a cemetery during the plague year of 1665.

Despite the pressure on space to bury the many thousands of victims of the plague, for whatever reason, the cemetery was not used, and in 1666 a Mr. Tindal took on a lease of the land, enclosed it with a brick wall, and opened the space as a cemetery for the use of Dissenters.

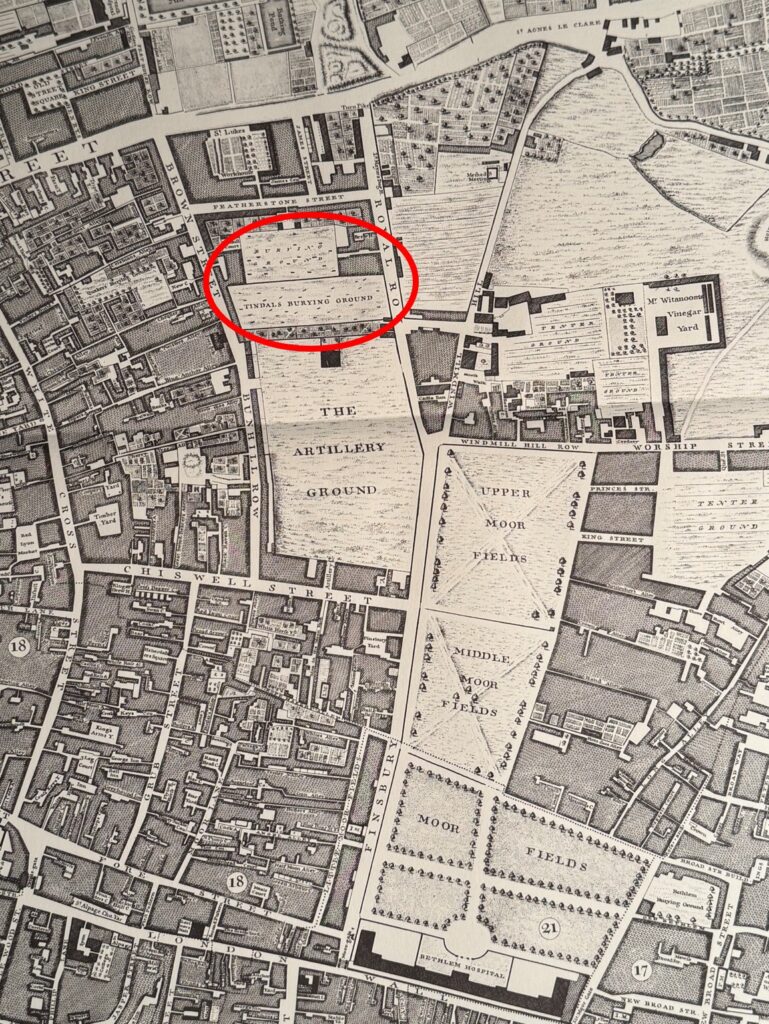

A wider view of the 1746 map, with the burying ground circled:

Old Street is running left to right along the top of the map, Royal Row, now City Road, runs to the east of the burying ground and Brown Street runs to the west. The name Brown Street has now been replaced by the extension of Bunhill Row along the western edge of the burying ground.

The use of the name Tindals Burying Ground was not confined to Rocque’s map, but was also in common use across multiple newspaper reports covering events in and around the burying ground, for example, from the Stamford Mercury on the 11th of February, 1768:

“On Saturday night last about ten o’clock, Mr. Hewitt, Watchmaker, in Moorfields, was attacked near Tindal’s Burying ground, by three footpads, who knocked him down, then robbed him of £32 and a dial plate, and beat him so terribly that his life is despaired of.”

Tindal’s Burying Ground was originally described as a place where Dissenters could be buried, and other terms such as Nonconformists were used to describe those within the cemetery. It was also described as the “Campo Santo of Nonconformity” as well as the “cemetery of Puritan England”.

These terms all described someone who did not conform with the governance and teaching of the established church – the Church of England. The 1662 Act of Uniformity defined the way that prayers, teachings, rites and ceromonies should be performed within the Church of England, and the 1662 date of this act explains why there was a need for a noncoformist burial ground four years later in 1666.

I cannot find out whether Mr. Tindal was a nonconformist, but it would perhaps make sense if he was.

The dead who would not have been welcome in a normal Church of England burial ground were buried at Tindal’s, for example in the following account of the burial of an executed criminal in 1760:

“Wednesday Evening, between Five and Six, the Body of Robert Tilling, the Coachman, who was executed on Monday last, for robbing his Master, was conveyed in a Hearse, attended by one Mourning Coach, to Tindal’s Burying Ground in Bunhill Fields, and there interred. The Rev. Mr. Whitefield attended the Corpse, and made a long Oration upon the Occasion, amidst the greatest Concourse of People that ever assembled in that Place; it is thought more than 20,000. The Corpse had been previously exposed in Mr. Whitefield’s Tabernacle near the Burying Ground.”

Robert Tilling was a nonconformist. After being taken from Newgate, he was hung at Tyburn on the 28th of April, 1760, along with four others convicted of burglary. In the report of his execution, he “made a long Speech, or rather Sermon at the Gallows, in the Methodist style”.

The origin of the name Bunhill Fields is interesting, and probably somewhat obscure. Most references talk about the name coming from the earlier name of Bone Hill, and that the site was used for informal burials and also for the 1549 dumping of 1,000 cart loads of bones from the charnel house of St Paul’s Cathedral.

The story of the dumping of bones is that there were so many, and after the following accumulation of the City’s dirt on top of the bones, a significant mound developed, on which some windmills were constructed.

If you go back to the larger extract from Rocque’s 1746 map, and look to the right of the Artillery Ground there is a couple of streets with names of Windmill Hill and Windmill Hill Row, so there must be some truth in the existence of windmills.

As usual, there are several variations of the name as well as stories of the area. There are a number of references that use the name Bonhill. In 1887, members of the East London Antiquarian Society were given a tour of the burying ground, where they were told that “The name was perhaps derived from Bon-Hill, a great tumulus which at one time stood on the Fen outside the City and marked an ancient British burying place, hence the name Bon-hill or Bone-hill fields.”

The City of London Conservation Management Plan states that in 1000 AD there were the “First corpses interred at Bunhill in Saxon times”.

The author Daniel Defoe in his “Journal of the Plague Year” implies that there may have been plague burials in Bunhill Fields, however that does not seem to be the case, and he was probably referring to the purchase of the burying ground which was later taken over by Tindal.

Bunhill Fields occupied a far wider area than just the burying ground, and earlier maps do show some hills spread across the fields.

As usual, there are many variations of names and stories, and it is impossible to be 100% certain of the truth of many of these. The fields were outside the walls of the City, for centuries much of the area was marshland, hence the name Moor Fields.

The entrance to Bunhill Burying Ground from City Road:

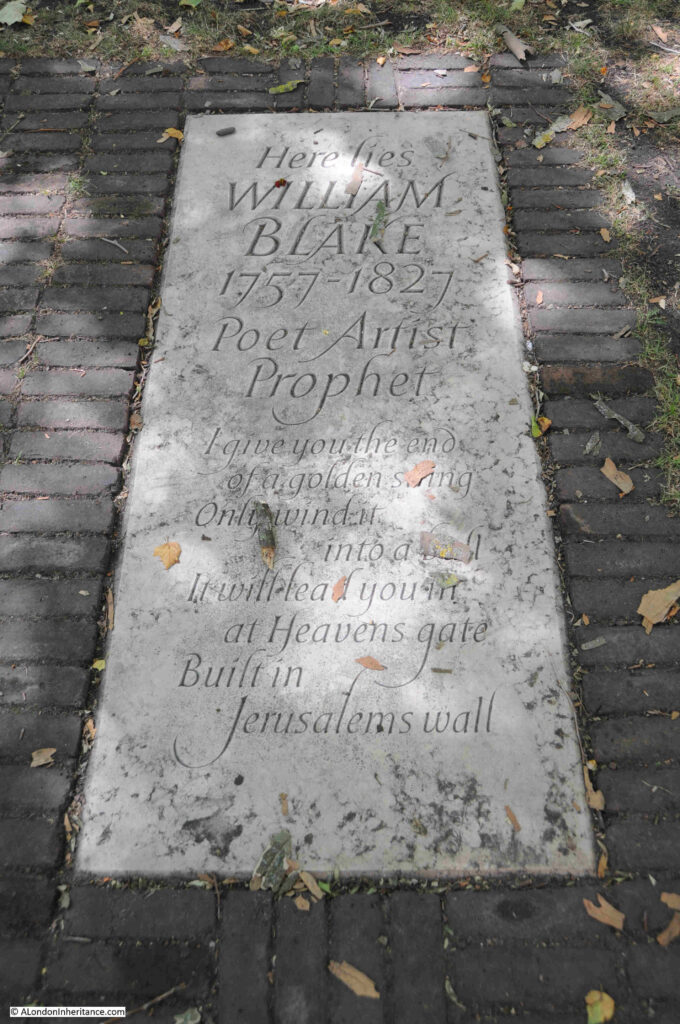

Gravestone to William Blake and his wife Catherine:

William Blake had some very complex religious views, and views of the roles of good and evil, human nature, sexuality etc. which were very different to those held by the established Church, hence his burial at Bunhill Fields.

The gravestone states “Near bye lie the remains of”, as Blake’s grave was the subject of damage over the years, as well as bomb damage in Bunhill Fields during the last war, so the exact location of his grave was lost.

Nearby there is a memorial slab which was installed in 2018 by the Blake Society following work by Portuguese couple Carol and Luís Garrido, who claimed they had identified the location of his grave:

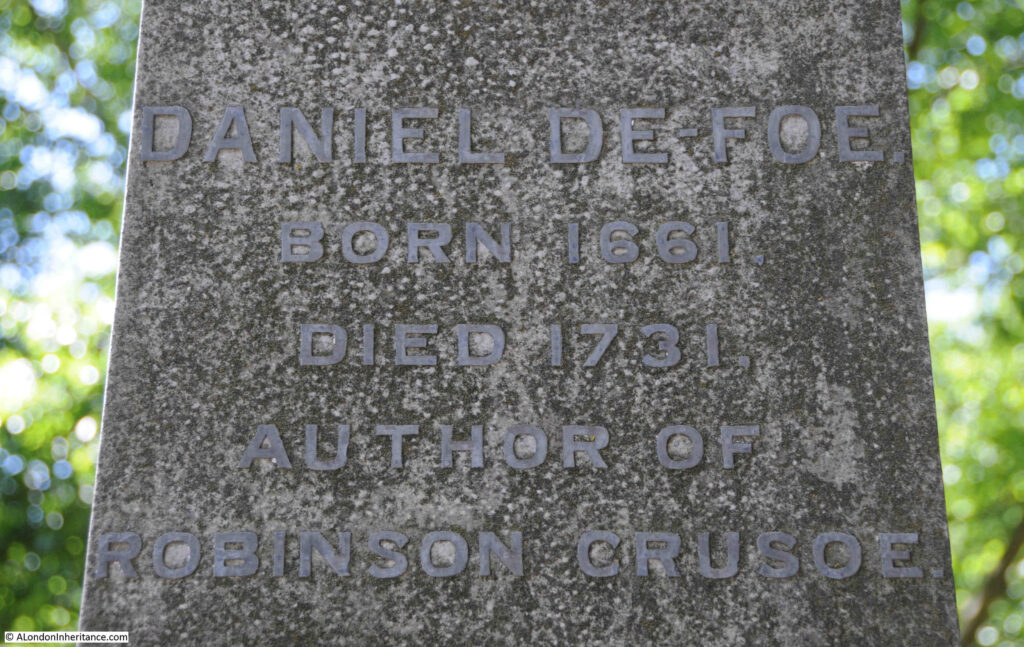

Monument to the author Daniel Defoe (which dates from 1870):

As recorded on the monument, Daniel Defoe was the author of Robinson Crusoe. The date of his birth, 1661, shows that he was very much too young to remember, let alone to write a first hand account of the plague in his Journal of the Plague Year, which in reality he used the accounts and experiences of others to write the journal.

There are a couple of graves at Bunhill Fields which seem to have been the focus of attention over many years. The first is from the 1920s series of books Wonderful London, where the grave of Dame Mary Page is shown:

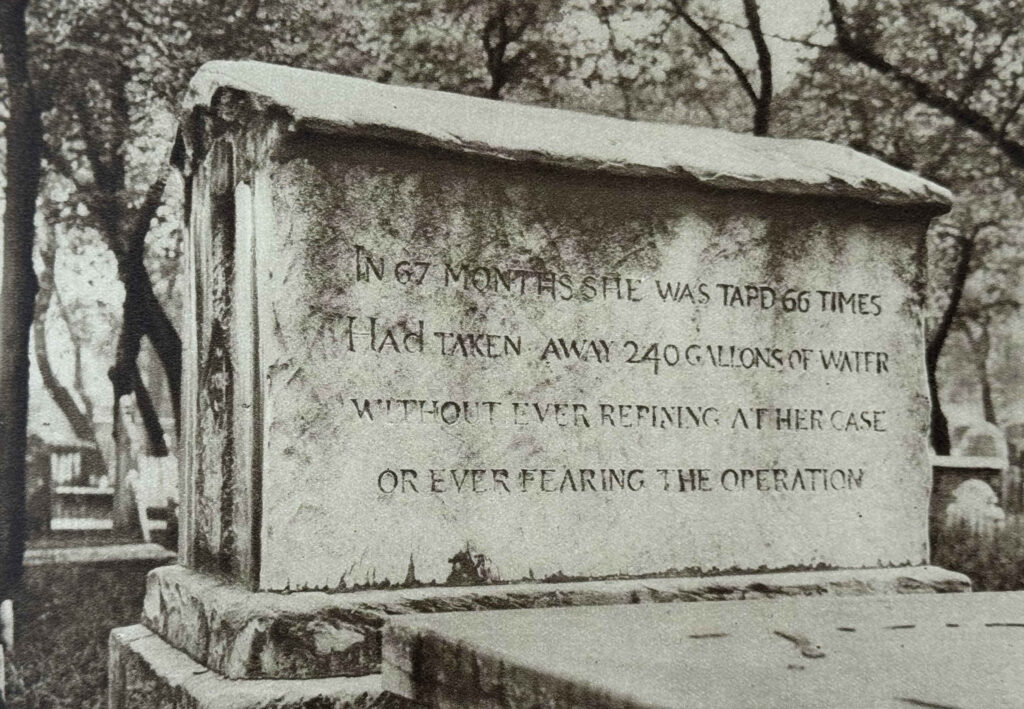

The focus of interest is not the front of the monument, but the reverse, where it is stated that Mary Page “In 67 months she was tapd 66 times. Had taken away 240 gallons of water without ever repining her case or ever fearing the operation”.

The front of the grave states that she was the “Relict of Sir Gregory Page Bart. She departed this life March 4 1728 in the 56 year of her age”.

Dame Mary Page was the wife of Sir Gregory Page. He owned a brewery in Wapping and was a Whig politician. He was also involved with the East India Company, including a period when he was a director of the company and this was the source of much of his wealth. He died in 1720 and was buried in Greenwich.

I cannot find any record of Mary’s religion, and it is strange that she was not buried with her husband. To have been buried in Bunhill Fields, she probably held some form of nonconformist views.

The rear of the monument today:

Bunhill Fields as a site is Grade I listed , and many of the individual graves are also listed, including the following grave of Joseph Watts, which is Grade II listed as: ” It is a well-preserved early-C19 chest tomb with still-legible inscriptions and high-quality relief carving”:

The land originally within Tindal’s Burying Ground is believed to have been extended in 1700 and again in 1788, such was the need for a site for nonconformist burials.

Following Tindal’s original lease, it remained a privately owned and managed burying ground until 1778, when it was brought into public management by the City of London.

Along with many other church yards and burying grounds in the mid-19th century, Bunhill Fields was closed for burials in 1854.

The King and Du Pont family monument which is Grade II listed:

The listing states that “It is a prominent and striking monument in an austere Neoclassical style, its polygonal form – derived ultimately from the Hellenistic-era Tower of the Winds in Athens – reflecting the late-C18 fashion for ancient Greek motifs”.

The vault beneath the plinth on which the monument stands holds a number of members of the King and Du Pont families from the late 18th century.

There is an interesting contradiction in attitudes during the 18th century (and indeed in later centuries), between those who were viewed as religious and displaying a range of admired personality traits and those who cost the state money.

Two different examples, both from the same newspaper on the 13th of December, 1754:

“Thursday evening was interred in Bunhill Burying Ground, the body of Mrs. Hannah Peirce, relict of that excellent Divine, Mr. James Peirce of Exeter. The Sweetness of her Temper, the exemplariness of her Behaviour, in every Religion and Condition, breathed a Spirit of a Religion, which is cheerful, patient, meek, and benevolent: Her whole Life was delightfully instructive, and in her 79th Year, she expired with remarkable Calmness and Composure”.

Meanwhile, on the same page as the above, there was an account of another who had just died, but this was very different where the person who had died was summed up by the amount they had cost the inhabitants of the parish:

“On Tuesday died Diana Nicholas, one of the Poor belonging to St. Nicolas Acorns in Lombard Street. In the Year 1691 she was found an Infant in a Basket in that Parish and taken care of: When she grew up she proved an Idiot, and forty years ago was got with Child, and, being unable to make known by whom, brought a further Charge on the Parish: So that it appears by the Accounts she has cost the Inhabitants near £20 per annum for sixty three Years”.

Two very different views of two deaths, where one was described with a range of perfect attitudes and character traits, whilst the other was down to simply how much they had cost the parish over their life.

Another of the graves that seems to be regularly featured when looking at Bunhill Fields is that of John Bunyan:

John Bunyan’s monument from the 1890’s book “The Queen’s London”:

John Bunyan was born near Bedford, and served with the Parliamentary forces during the English Civil War. He originally followed the Church of England, attending services in his local parish church.

A chance meeting in Bedford resulted in Bunyan joining the Bedford Meeting, a nonconformist group.

Bunyan took his nonconformist views and preaching seriously, to the extent that he served many years in prison, And it was during one of his spells in prison that he wrote his best known work “A Pilgrims Progress”.

His writing became more widely known after his death, and in the 18th century there were multiple editions of A Pilgrims Progress published, including cheap editions, and editions published in regular instalments.

The book was described as an allegorical writing, describing the journey of Christian from his home, the City of Destruction, to the Celestial City, which has been described as either Heaven or the Holy Land. There were also references to the Celestial City being London, and Christian’s Journey being Bunyan’s journey from Bedford to London.

The grave apparently belonged to one John Strudwick , in whose house in Snow Hill, Bunyan had died in 1688:

The gravestone of Thomas Rosewell. The gravestone is listed, not because of the gravestone (which I think is a later addition or replacement, rather as to who it commemorates, as the listing states *It commemorates a prominent late-C17 Dissenting minister, remembered for his infamous treason trial in 1684*:

The story of Thomas Roswell is one of religious persecution. He was born in Bath and arrived in London in 1645 where he trained as a silk weaver.

London in the middle of the 17th century must have been a hotbed of religious and political divide and conspiracy. Not just with the Civil War, but with the established Church, Catholicism and the many nonconformist groups.

Soon after his arrival in London, Roswell came into contact with the Presbyterians, which led him to train as a nonconformist minister. He became a private tutor and also served as a rector in parishes in Somerset and Wiltshire.

The years following the restoration of the Monarchy and Charles II were a time of persecution of nonconformists, and Roswell was forced out from his parishes in 1662, even though he was a firm Royalist.

Persecution continued and in 1684 he was put on trial for high treason, accused of speaking seditious sentiments during a sermon.

The judge at his trial was Lord Chief Justice, George Jeffreys, also known as the Hanging Judge due to the high number of defendants who were found guilty, resulting in Jeffreys passing the death sentence.

Roswell was also found guilty, and sentenced to death, however there was a significant public outcry and early the following year he received a Royal Pardon.

A look across Bunhill Fields:

An Act of Parliamnet obtained by the City of London in 1867 preserved Bunhill Fields as an open space, and in 1869, the grounds were open to the public.

The burying grounds were not spared during the Second World War, and they suffered serious bomb damage, and post war there has been a continual series of restorations of both the grounds and the gravestones and memorials, enabling the listed memorials to be removed from the heritage at risk register.

Bunhill Fields was also the location for an anti-aircraft gun which probably did not help with maintaining the condition of the site.

The walls and railings surrounding Bunhill Burying Grounds are Grade II listed and date from multiple periods from the late 18th century through to the late 19th century, along with later repairs and renovations.

Apart from a few monuments and graves, the majority are within an area surrounded by railings. It is possible to gain access to graves within this area by asking an attendant.

I have only touched on a very, very small number of the graves at Bunhill.

According to City of London records, there are 2,300 memorials within the burying grounds, and there are believed to be around 123,000 burials.

Each tells the story of those involved in nonconformist and dissenting religious traditions, and many, including that of Thomas Roswell show the risks that having a different belief to the established Church could entail.

And the burying ground now commonly known as Bunhill Fields, almost certainly owes its existence to Mr. Tindal who took a lease on the land in 1665 / 1666, enclosed the ground and opened the burying ground.

Bit of a typo.. Plaque? Should be plague.

The dentists were very busy that year!

Great article! City Garden Guides (city garden walks.com) offer regular guided walks at Bunhill, including access inside the railed off areas.

Thank you for posting this information. I always enjoy reading your posts together with information. relating to them.

On http://www.findmypast.co.uk they have the Bunhill Fields burial records. Some volumes are transcriptions of the stones and monuments. It is beautifully written with some wonderful illustrations/line drawings of crests and some shapes of tombs. Not sure where the originals are but they are fascinating reading. As is the place. Thankyou for this post.

I have several ancestors buried in Bunhill Fields – as far as I know only one of them has a surviving tomb. They were pewterers, carpenters, tallow chandlers and so on. They were married in Anglican churches, as this was a legal requirement from which only Jews and Quakers were exempt. But for the most part their children were not baptised, with their births being recorded elsewhere. I have no idea what form their non-conformism took

Why is John Milton missing ? He wrote the epic tome of Paradise lost

Regards Keith

My ancestor Stephen Williams of the Poultry, a leading member of the Little Prescott Street Strict Baptist Chapel, was buried in a vault at Bunhill on 19 June 1797 aged 86 at a cost of £5 5s 6d. Despite several visits I have been unable to locate the vault due to the deterioration of the stones. However, on one visit my son was passing through the graveyard and the sun caught an upright gravestone in such a way that the lettering could be read. It was the grave of Stephen Williams’ two infant children, John and Susanna, who had died nearly 50 years previously! I went to see the gravestone for myself but it was completely illegible Fortunately my son had photographed it when he visited and the lettering is quite clear to see. I suspect more gravestones and vaults could be identified with the help of raking light.

Mary Page must have been robust as well as lucky. Losing 3 gallons of body fluids by tapping every month for over five years….amazing

Bunhill fields was not a pleasant place to live alongside because of the smell of decomposing corpses.

My great grandfather John Gladding lived opposite the gates at 20 City Road He wrote an anguished letter to The Times published on 27 Sept 1848 complaining about this, and berating the minister who he said wanted as many bodies buried there as possible because of the fees he received for each one,

Fascinating, thanks – part of ‘The Great Stink’ of 1848, the closure of many London churchyards, and of cesspits around that time. Then the cholera epidemic of 1853, leading to John Snow’s discovery that it wasn’t ‘miasma’, ie bad smells, that caused disease, it was, in his famous case, water contamination at the Broad St pump. Enter Brunel and Bazalgette.

As a child I played all around Bunhill Row, I lived in Old St. the area was mostly derelict following the war and was a great place to play. I well remember the cemetery but had no idea of its history or the famous people interred there. Because it looked derelict I just assumed it was “full up”!

What a wonderfully interesting article – I enjoyed it so much.

Very interesting article, as always!

An excellent read as always. I did have to research what the “tapping” of Mary Page indicated–paracentesis, a surgical puncture of the abdomen to drain fluid, nearly once a month for 5 1/2 years.

I remember attending City and Islington College close by. We would eat our lunch in Bunhill Fields, an island of tranquility in a hectic City of London.

Thank you. I live nearby and walk in and through Bunhill Fields weekly. Additionally, people may be interested to know that John Wesley’s house is just across Moorgate from the entrance shown. And the historic Quaker burial ground is just a block to the west of the Bunhill Row entrance to the Fields.

I work very close to Bunhill Fields – this is so very interesting ! Thank you

There was no nearby church ?

Interesting read! Anyone know in relation to Mary Page:

“In 67 months she was tapd 66 times. Had taken away 240 gallons of water without ever repining her case or ever fearing the operation”.

What was ‘tapd’?

One of our ancestors, Thomas Hall, a well-known taxidermist who had a business on City Road, was buried in Bunhill Fields, where a young daughter had been previously buried. Later members of the family, however, were all buried at Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, which was also a non-conformist burial place

I’ve visited this place a number of times, mainly when attendng meetings of the Family History Federation,(FHF) formally the Federation of Family History Societies, (FFHS) that have occasional meetings in The Wesleyan Methodist Chapel that is almost opposite on City Road.

I found more information in a book called “Bunhill Fields” written by Aldred W. Light and published in London by C.J.Farncombe & Sons , Ltd., in 1933 (p 183/4):

Dame Mary Page and her husband were persons of considerable wealth and influence, and were members of the old Devonshire Square Church. They befriended distressed Dissenters as much as possible, and after the death of Sir Gregory, Lady Page distributed her wealth with a lavish hand, and by her will bequeathed considerable amounts for the succour and relief of poor fellow members. Her ailment was most painful and distressing, and she was frequently carried into the family pew, as she was always anxious to attend the services. She was an accomplished woman, a kind and affectionate friend, and a lover of Christian people, no matter what their station might be. A short time before her death on being asked whether she had a good prospect of another world, she replied, “I have, I have” she died without a groan or struggle, on March 4th, 1728