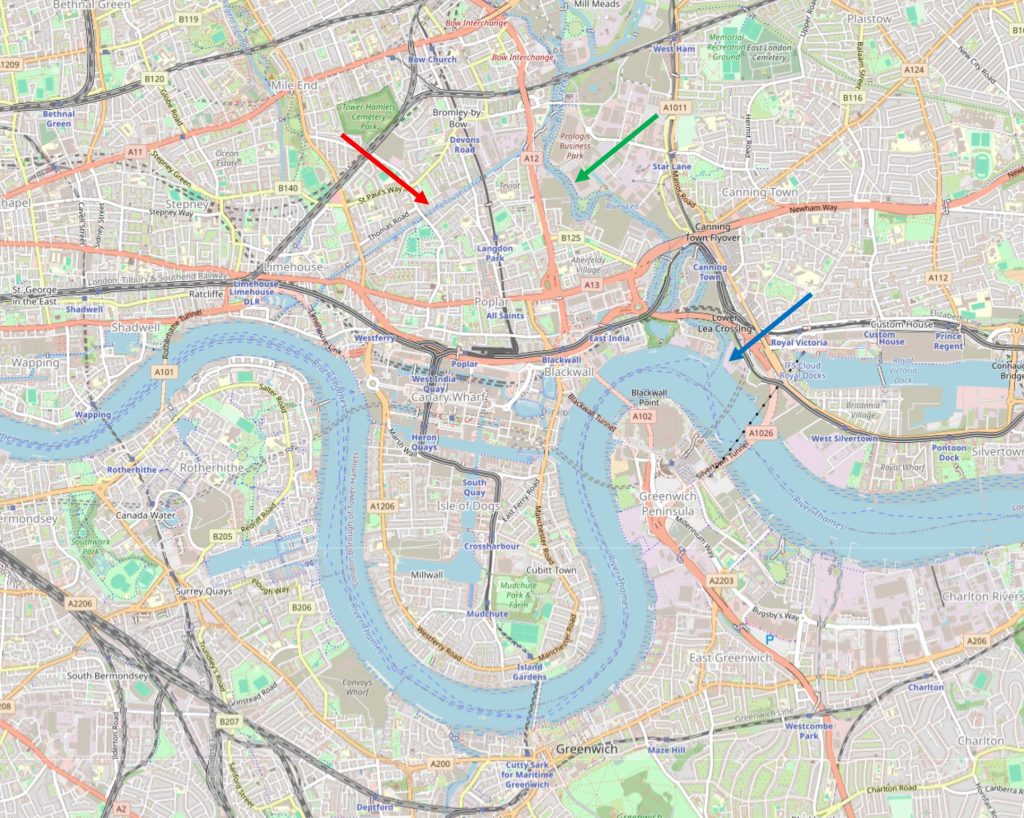

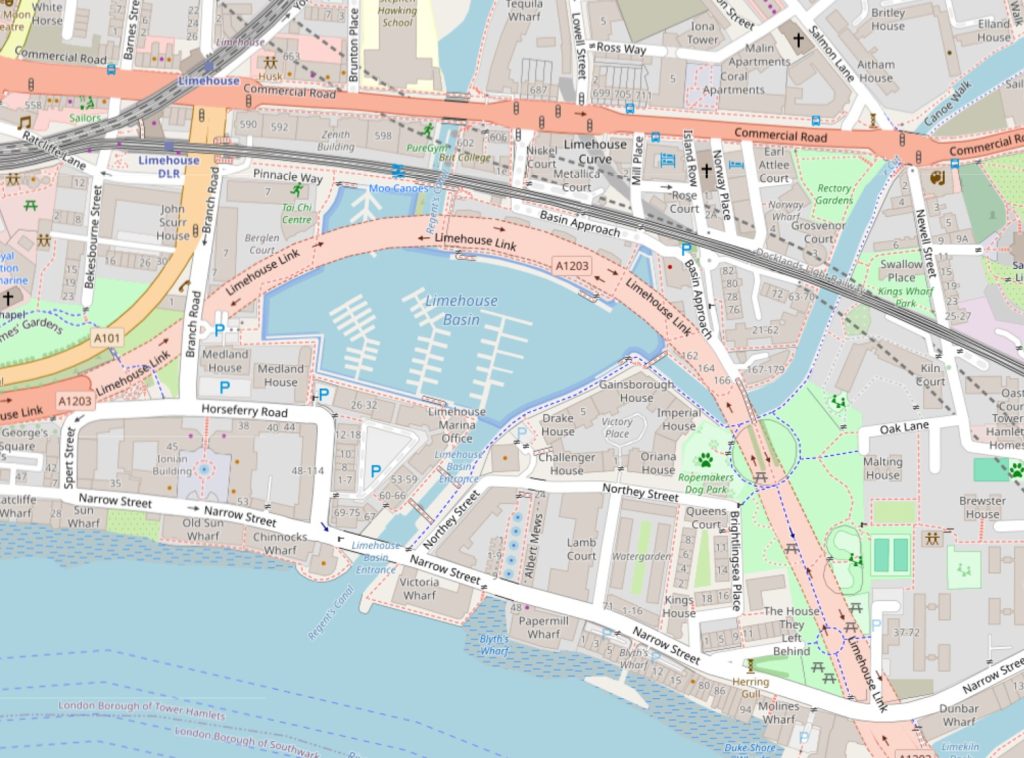

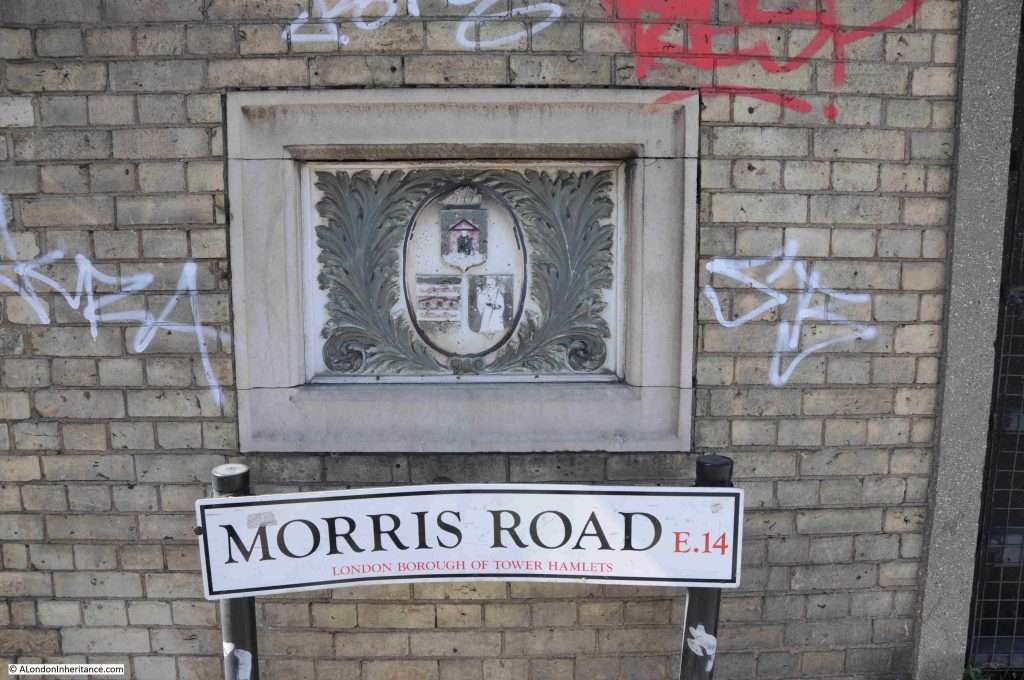

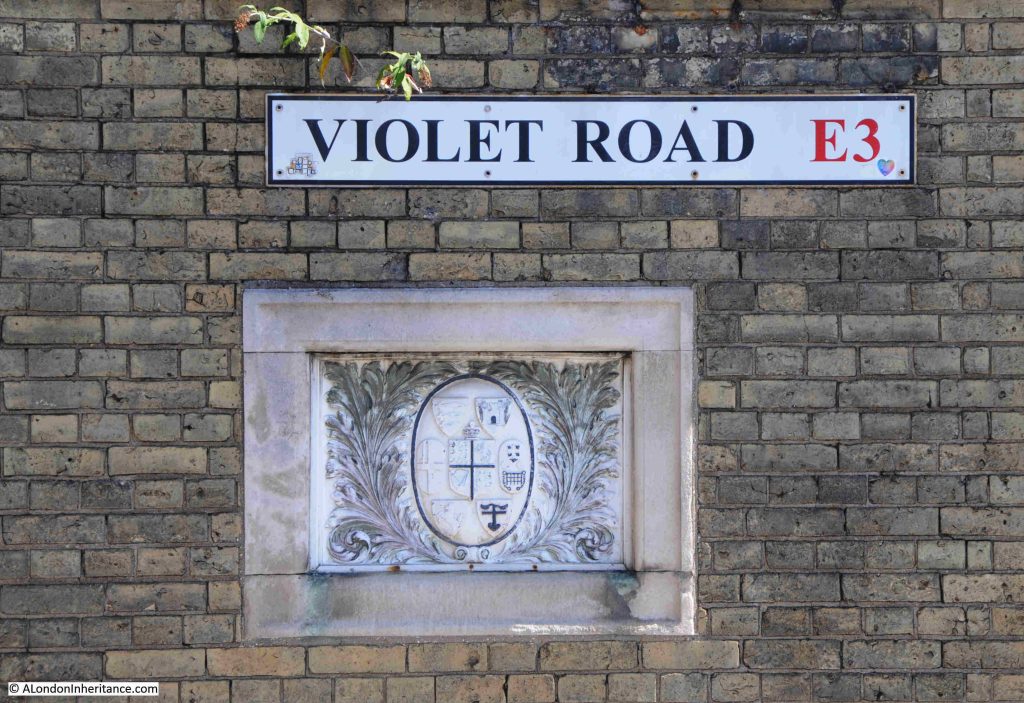

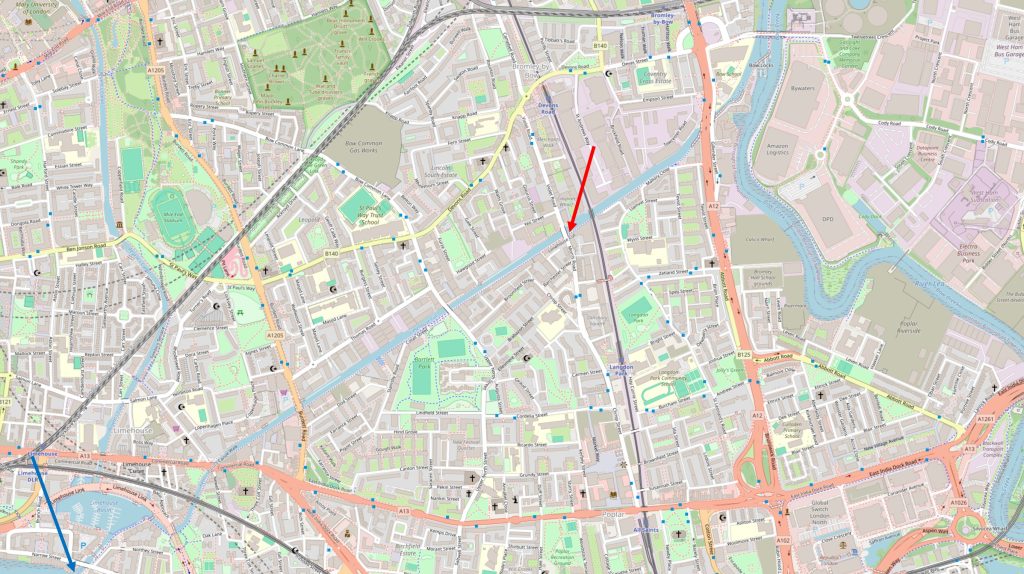

In the first part of my walk along the Limehouse Cut, I started where the Cut once entered the River Thames (blue arrow in the following map), and ended where Morris and Violet Roads cross the Cut (red arrow). In today’s post, I am continuing along the Limehouse Cut to where it meets the River Lea and walking up towards Three Mills Island (map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

From here onwards, there are not so many people walking along the tow path. The first part of the walk has been reasonably busy with walkers, joggers and cyclists.

If you do walk the same route, the only thing to watch out for is the occasional cyclist who does not give any warning of their approach, races up behind you, and when you are aware of them coming up behind, the distance is insufficient for both pedestrian and cyclist to safely move to opposite sides of the tow path. One cyclist almost ended up in the water when we both moved to the same side, and the distance between us required an emergency swerve.

This was only a single instance, the majority of cyclists are very considerate of pedestrians.

A short distance along from the Morris and Violet Roads bridge is the bridge that carries the Docklands Light Railway across the Limehouse Cut. As I passed under the bridge, a train passed above:

This is the section of the DLR that runs between Poplar and Stratford, Devons Road station to the north west and Langdon Park station to the south east. It was originally the route of the North London Railway, and on the land to the right of the above photo, there was a complex of engine and carriage sheds with multiple tracks to serve these, and provide a connection with the main railway.

The Limehouse Cut now has a much more industrial / commercial feel to the land alongside the Cut, which probably explains why there are not so many people walking this section than along the earlier part of the walk:

Very few remains of earlier industry survive, however is the metal frame of an earlier building surrounding a new building seen to the left in the following photo. This was originally a furniture factory and what is now a rusty metal frame once extended over the Limehouse Cut to provide a gantry with facilities to load and unload barges on the water:

Further along there is a length of metal piling and concrete infill extending into the water. I cannot find any similar features in earlier maps, and it looks relatively new. No idea of the purpose:

For almost the entire length of the route, the Limehouse Cut has been a straight line. It was built at a time when north of a small area along the river, there was no development, so the original builders dug the Cut through what was rural land.

We are now though approaching the end of the Limehouse Cut and there is a slight curve in the route:

Well signposted:

The towpath changes here and offers two routes. To the right, the footpath runs up to the six lanes of the A12 road, and to the left, and new walkway takes the walking route along the side of Limehouse Cut:

And under the A12:

This walkway was needed when the A12 was enlarged. This section has always been a narrow part of the Cut, and a place where Leonard’s Road crossed, however the routing of the A12 from Stratford down to East India Dock Road (A13) and the Blackwall Tunnel required a new, significantly larger bridge to be built.

There were a good number of ducks along the length of the Limehouse Cut, and after walking under the A12, one of the breeds seen on the water has been painted on the wall of a building to the side of the Cut:

Looking back towards the bridge thar carries the A12, and next to it another bridge for Gillender Street. The original wall of the Cut can be seen on the left:

At the end of the walkway, the water opens up as we approach the River Lea:

I have been using the name River Lea throughout my posts on the Limehouse Cut, although two spellings are used for the river that the Limehouse Cut was built to bypass. Lea and Lee.

The source of the River Lea is in Bedfordshire, to the north of Luton. The river runs through Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, on the edge of Essex before heading into Greater London.

The name Lea is used from the source to Hertforshire, and from Hertford to the Thames, both Lea and Lee are used.

The Lee comes from the Lee Navigation.

The reason why the Limehouse Cut was built was to bypass the River Lea as it ran to the east of the Isle of Dogs, to provide a more direct route to the City of London, to avoid the bends in the River Lea as it approached the Thames and to avoid the tidal sections of the Lea.

Similiar issues resulted in the construction of the Lee Navigation. This is a canal built on a parallel route to the River Lea, with an aim of smoothing out many of the bends in the Lea, providing additional space for boats, along a route where water levels could be managed. In a number of places the Lee Navigation and River Lea are combined as a single channel.

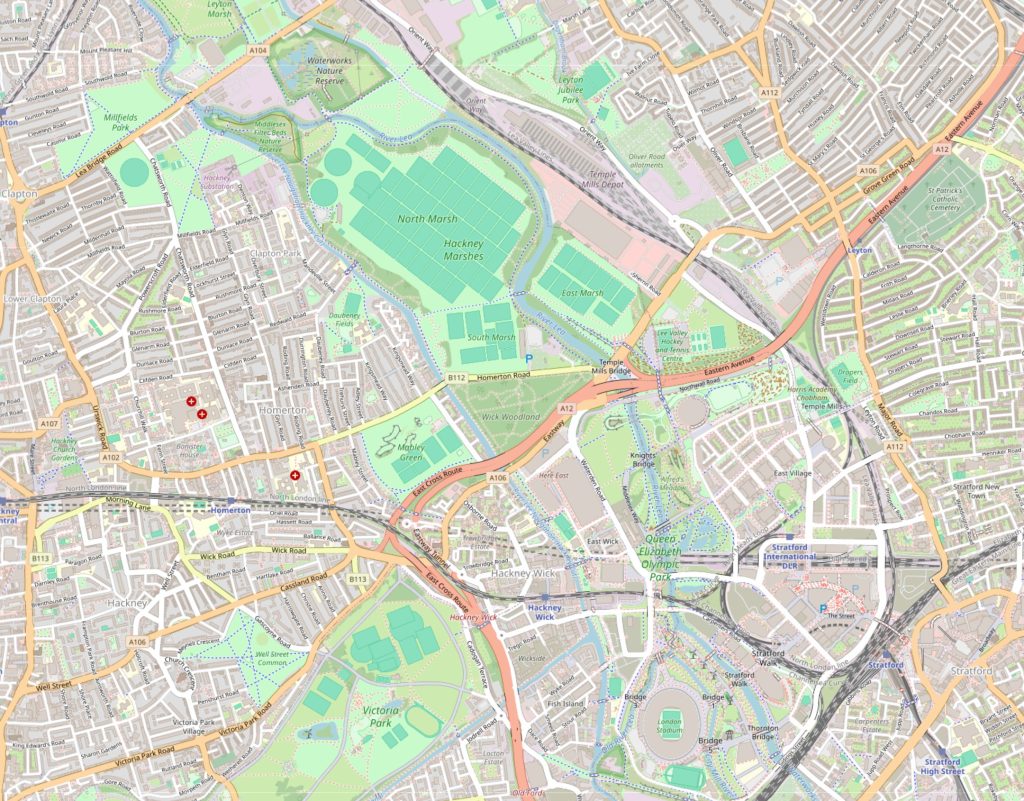

This is why a look at a map reveals a complex route of parrallel waterways, which often combine.

In the following map, the River Lea runs to the right and the Lee Navigation to the left, as they both pass through, and then head north from Stratford (map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

The River Lea had been subject to many previous attempts to manage the use of the river, make improvements and control water extraction. See my post on the New River for where this early 17th century approach for providing water supplies to the growing city met the Lea.

The 1767 River Lee Navigation Act authorised a number of improvements, including the construction of new lengths of canal, and further acts, such as the 1850 Lee Navigation Improvement Act allowed additional construction, including a number of locks along the route.

The parallel running, sometimes combining and both routes serving the same source and destination have resulted in both Lea and Lee being used, however Lea is for the river and Lee is for the Lee Navigation, the fully navigable canal system built over the last few centuries, that provides an easier to use route than the river, and we see this name as we approach the point where Limehouse Cut, Lee Navigation and River Lee combine:

And it is here that we find the Bow Locks:

Bow Locks control access from where the Limehouse Cut meets the River Lea, and Bow Creek, also known as the River Lea which runs down to the River Thames, and is tidal:

In the background of the above photo there is a grey / white bridge. This is a 1930s foot bridge that spans the waterways, and although I was at the end of the Limehouse Cut, I wanted to explore a bit further, so headed over this footbridge:

From the footbridge, we can look over the lock and along Bow Creek / River Lea as it heads towards the Thames. The mud banks on the side show that this stretch of the river is tidal, and demonstrates why the lock is needed. On the right edge of the photo, a small part of the Limehouse Cut can be seen. It is these locks that ensure there is a stable height of water in the Limehouse Cut:

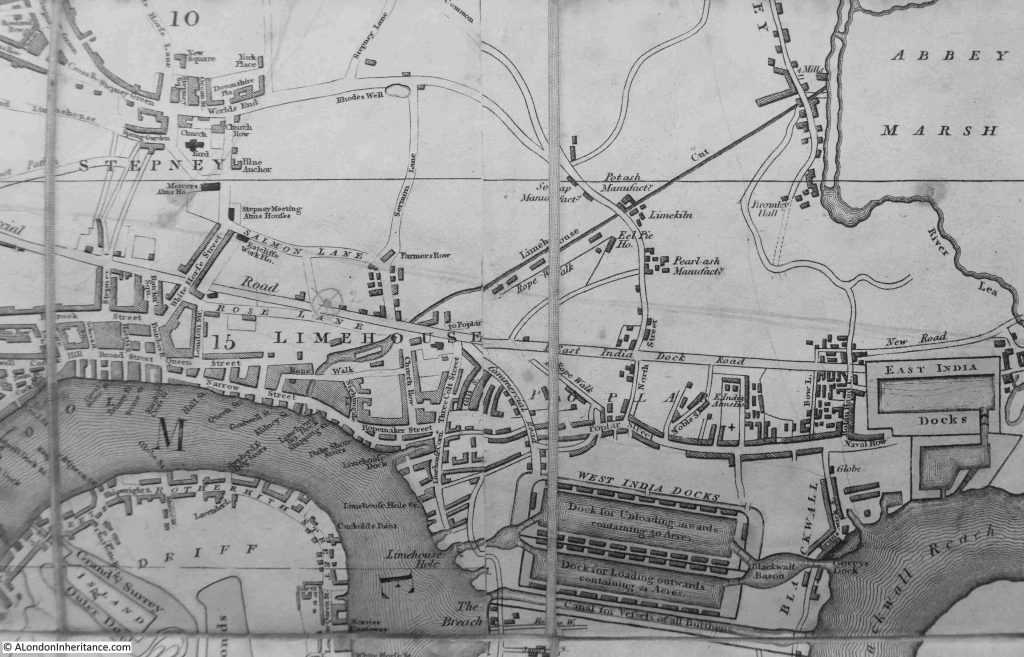

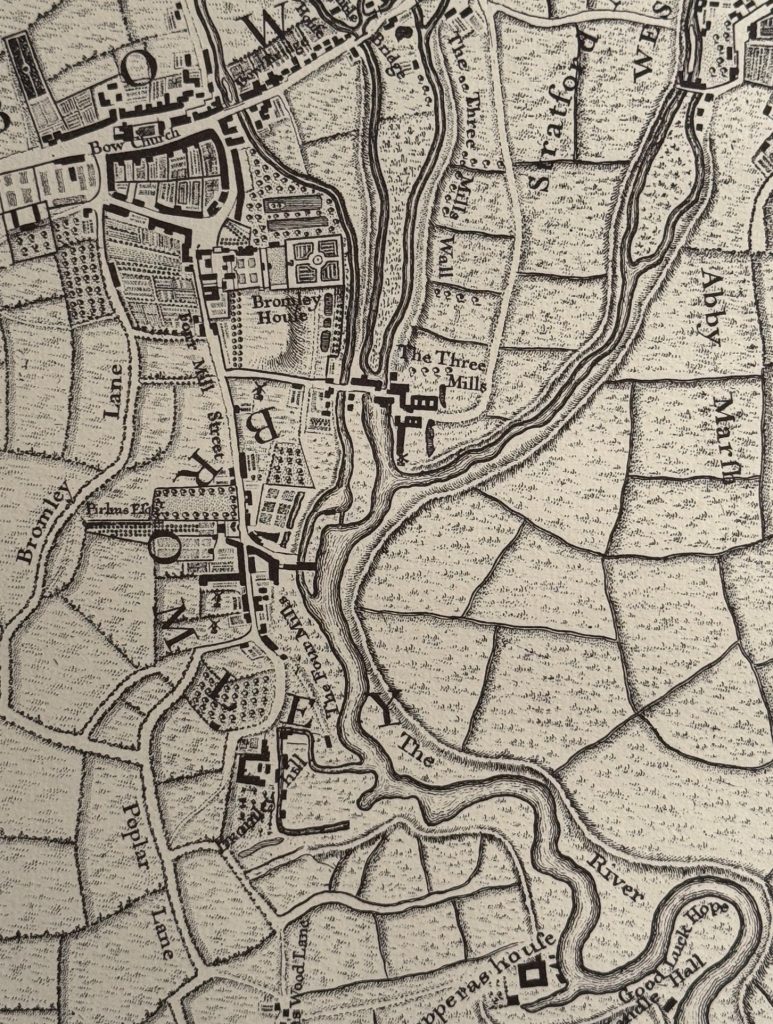

Around 20 years before the completion of the Limehouse Cut, where it joins the River Lea was an area of fields, orchards, gardens and limited housing. In the following extract from Rocque’s map of 1746, you can see the world BROMLEY curving to the left of centre. The Limehouse Cut went through the letter M as it ran from bottom left up to join the River Lea:

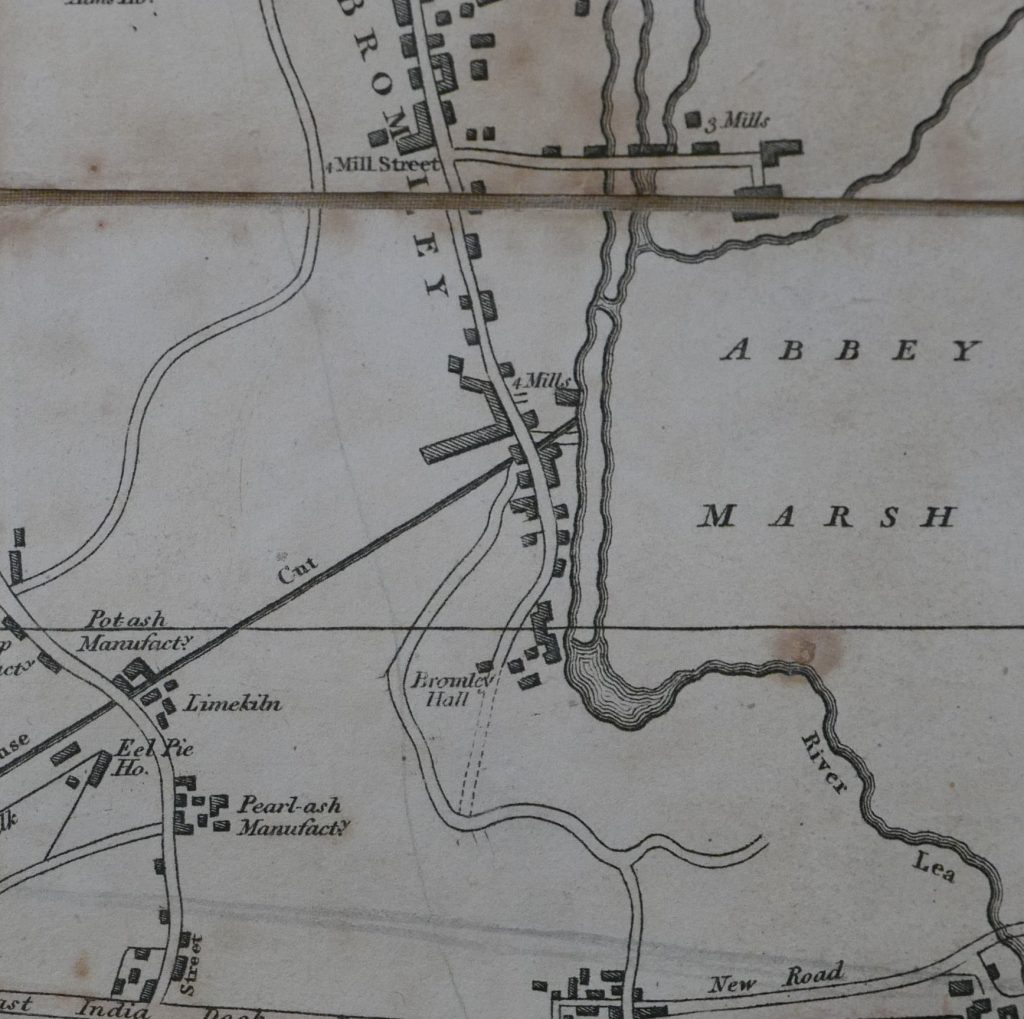

To demonstrate the complexity of the River Lea / Lea Navigation, and the associated waterways in the area, the following extract is from Smiths New Plan of London from 1816, and shows the straight line of the Limehouse Cut joining one of the strands of the Lea:

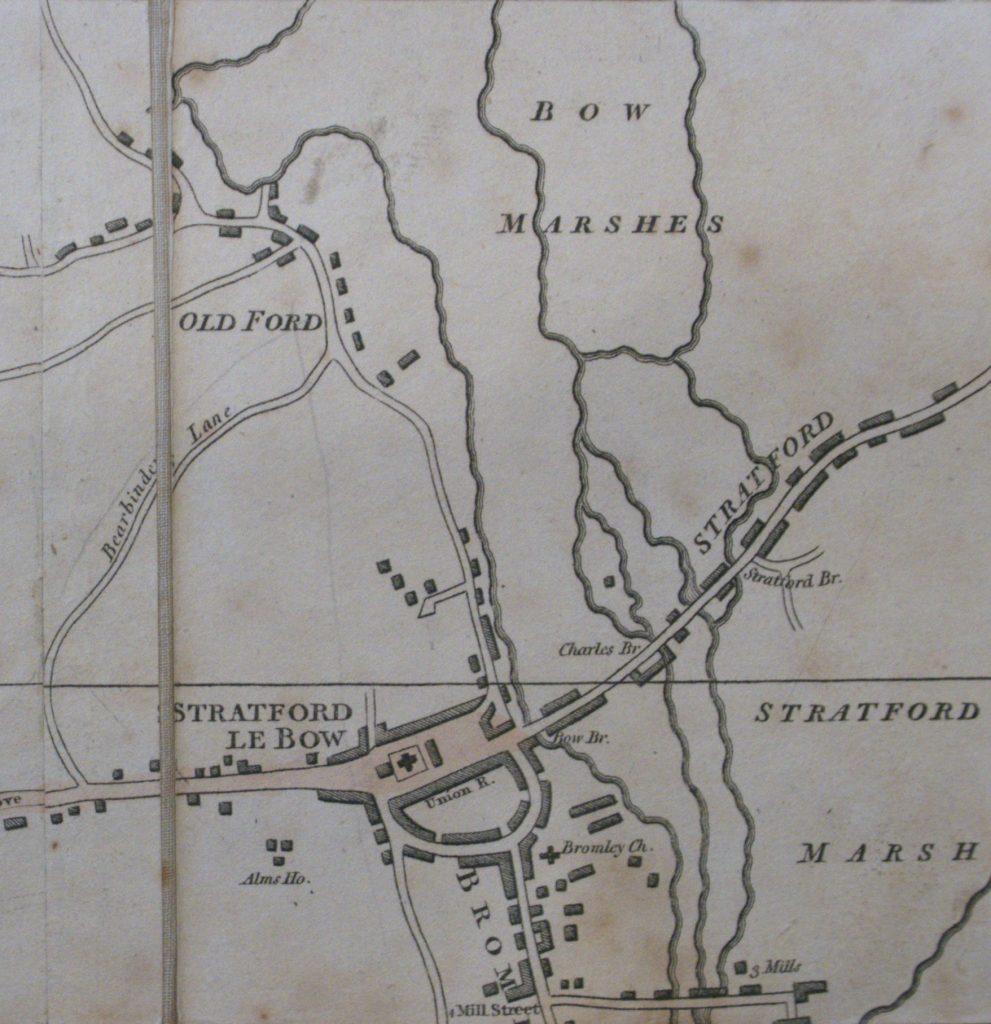

The complexity of this water network can be shown using the same map, but a bit further north in the area surrounding and to the north of Stratford. The names Stratford Marsh and Bow Marshes demonstrate the nature of the surrounding land, and how the Lea river system has had an impact on this area for centuries:

After that slight digression, I am still on the footbridge, and this is the view looking north with the bridge carrying Twelvetrees Crescent across the Lea:

The orange boat moored in the above photo is an old British Gas life boat, which I assume came from either a North Sea gas / oil rig or a ship – and is now performing a very different use.

Walking under Twelvetrees Crescent Bridge, and there is a walkway that once provided access to the gas works just to the east:

Further on is the bridge that carries both the District and the Hammersmith & City lines over the Lea:

Along this stretch of the Lea is a rather isolated but colourful piece of sculpture. I knew it was sculpture as the small blue plaque on the concrete base states “Please do not climb on the sculpture”:

The sculpture is part of “The Line”, and the following is from the project’s website: “The Line is London’s first dedicated public art walk. Connecting three boroughs (Newham, Tower Hamlets and Greenwich) and following the Greenwich Meridian, it runs between Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and The O2 on Greenwich Peninsula. The Line features an evolving programme of art installations (loans and commissioned works), projects and events, illuminating an inspiring landscape where everyone can explore art, nature and heritage for free.”

The above work is by Rasheed Araeen, who “is renowned for his use of an open cube structure with diagonal support in his sculptural works”.

A map of the route of The Line, and the works along the route, can be found at this link.

Looking across the branch of the Lea that runs to the right of where I am walking, are the old gas holders of the Bromley by Bow gas works:

The 1914 revision of the OS map shows the round circles of the gas holders, and a short distance below is the Bromley Gas Works, who had their own dock leading from the River Lea. A small part of this dock still remains in the middle of an industrial estate which has taken over the land of the gas works:

(Map ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

The following photo from Britain from Above shows the Bromley by Bow Gas Works in 1924. The River Lea can be seen running below the gas works buildings, and the dock that served the works can be seen coming of the Lea on the right of the photo, and running into the heart of the works. The gas holders are off to the left of the photo, a short distance from the works:

The Bromley by Bow gas works have a fascinating history and hopefully will be the subject of a future post, but for now I am continuing along the River Lea to my final stop.

In the complex web of waterways, as we approach Three Mills Island, we can see through the trees and bushes that line the river, the Channelsea River, one of the old rivers that ran across Bow. It now runs up to Abbey Road where it disappears into a culvert, and also forms the southern part of the channels that now makes Three Mills Island, an island:

If you go back to the 1746 and 1816 maps, you will see the Channelsea River heading east from the Lea, just below the Mill.

Back looking along the River Lea, and if it was not for the tower blocks in the background, this idyllic view could be deep in the countryside rather than being in east London:

The brick buildings to the right of the above photo are those of the old mill buildings on Three Mills Island, which look glorious as you approach:

Although now an island due to the rivers that surround the site, it has not always been an island as the maps earlier in the post show. The site became an island when a channel along the east of the site was built from the Channelsea River back up to the River Lea.

Mills have been operating here for centuries, making use of the power of the water and tides along the River Lea. The buildings that we see today are mainly 18th century and range from Grade I to Grade II listed:

Back in 1972, the Architects’ Journal featured a lenghty article on the sites in east London that were considered at risk. Bombing, post war industrial and population decline across east London resulted in a range of buildings that were considered at risk of demolition.

I started working through all the sites back in 2017, to see how many had survived. The first post in the series is here. I still have a small number to finish off.

Given what a wonderful set of buildings we see today, it is surprise (or perhaps not given the attitude to many old industrial buildings at the time), that the mill buildings were considered at risk, including what is the world’s largest surviving tidal mill.

At the end of the street in the above photo is 3 Mills Studio, a studio complex built on the site of the Three Mills Distillery, and the studios where Master Chef is filmed.

As with the gas works, the history of this site deserves a dedicated post, which will hopefully appear in the not too distant future.

It is a really interesting walk along the Limehouse Cut from the old entrance to the Thames, up to the River Lea, and along the Lea to Three Mills Island.

Limehouse DLR station is near the start of the walk and Bromley by Bow station is a short walk from the end (walk to the north of the nearby Tesco store, underneath the A12, then south to the station.

The Limehouse Cut was a clever answer to the challenges of 18th century cargo transport from the Lea to the City of London, along with the docks and industry along the Thames from Limehouse to the City.

The Limehouse Cut eliminated the need for a long detour around the Isle of Dogs, the curving southern stretch of the Lea into the Thames, and the tidal challenges of this stretch of river.

Today it provides the route for a fascinating walk.