One of the pleasures of writing the blog is finding out more about an area I have already covered. Back in February I wrote a post about Horn Stairs, Cuckold’s Point and Horn Fair, and whilst at the stairs I had walk around Rotherhithe Street, and a block of flats seemed vaguely familiar.

Back home I looked through the photos of a boat trip my father had taken along the Thames in August 1948, and found the flats I walked past in Rotherhithe Street.

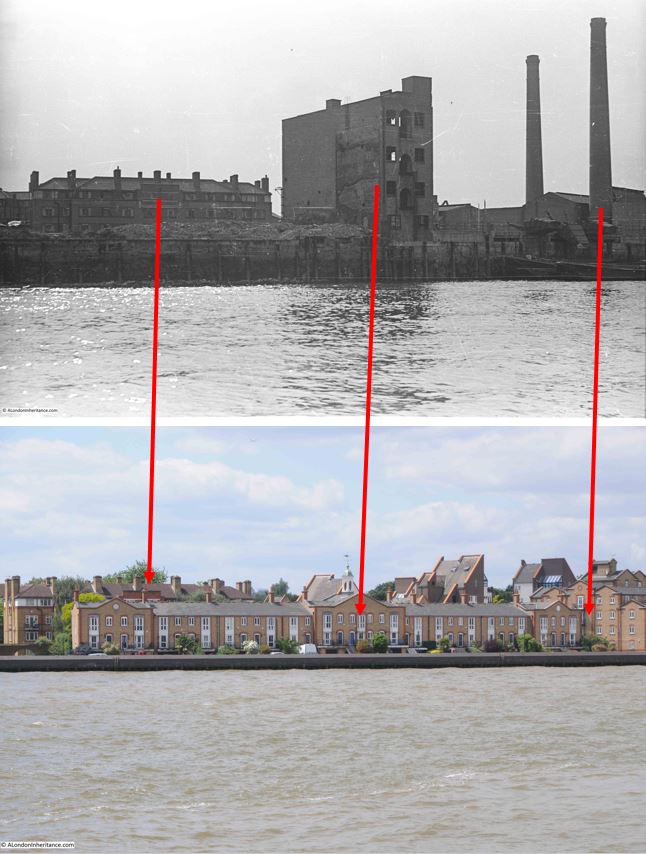

This is the August 1948 photo of Sunderland Wharf and Ordnance Wharf, Rotherhithe, with the block of flats in the background:

The same view, seventy six years later in 2024:

in the following image, I have mapped the 1948 photo to that of 2024. The flats are just about visible behind the new houses which line the river. I have also marked where the tall building and the chimney nearest the river were located in the area as seen today:

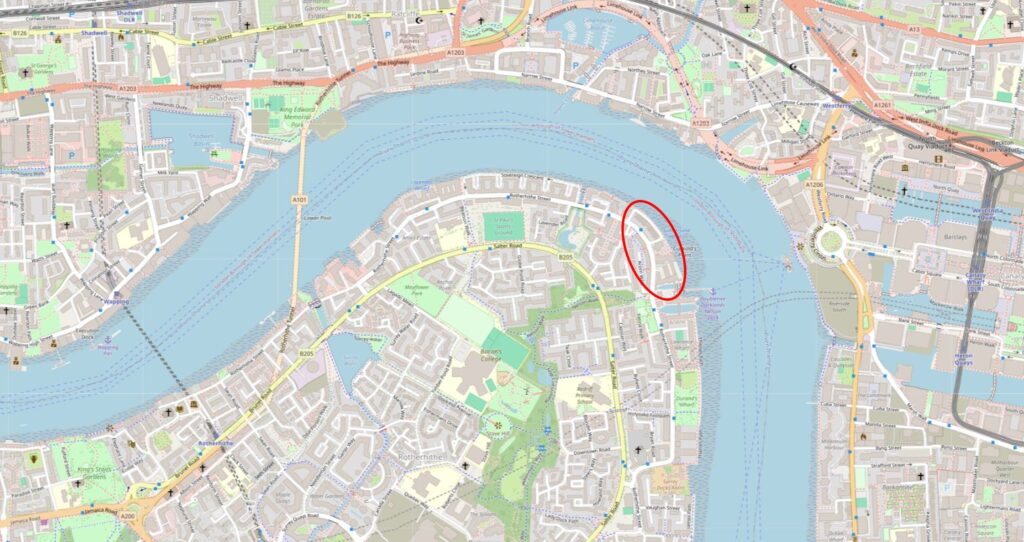

The area covered by today’s post, is highlighted within the red oval in the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

There is a whole sequence of photos that my father had taken in August 1948 on a boat trip from Westminster to Greenwich. I have already featured a number in the blog, but there are a number where there are no easily identifiable features, such as a wharf name on a building, and the buildings along the banks of the river, particularly on the south side, have changed so much that identifiable features are rare.

Luckily, it was finding the block of flats that enabled the location in this photo to be identified.

The series of photos show a very different London to the east of Tower Bridge. Significant bomb damage and an area of warehouses and industry, often very dirty and polluting industry.

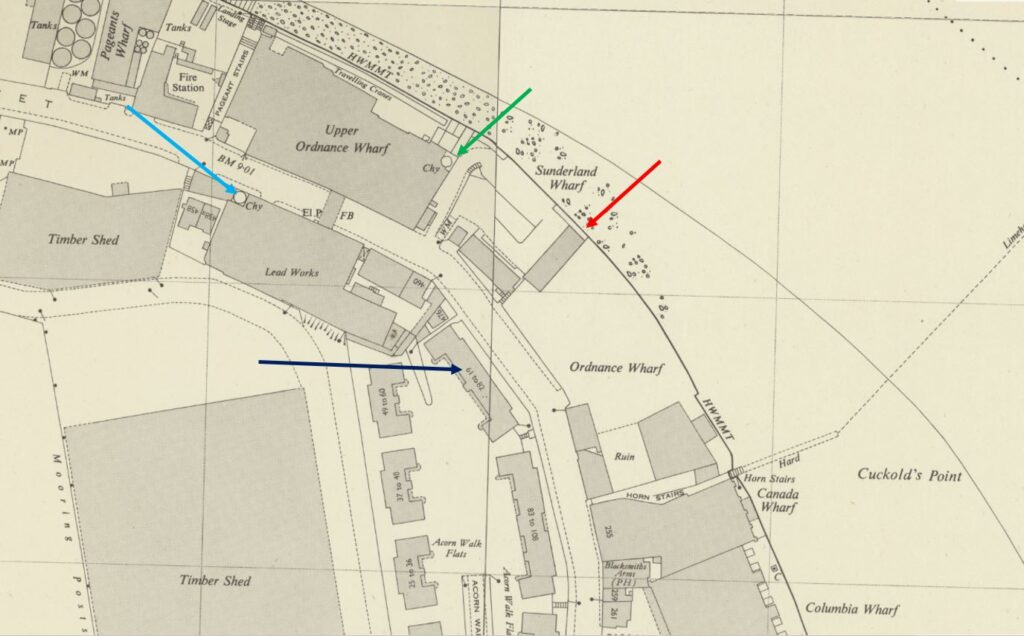

The following extract is from the 1949 revision of the Ornance Survey map, so only one year after my father’s photo, and the features in the photo can be seen in the map.

I have highlighted them as follows:

- Dark blue arrow – the block of flats seen in the background

- Red arrow – the remaining tall and narrow building

- Green arrow – the chimney nearest the river to the right of the photo

- Light blue arrow – possibly the second chimney in the photo. It appears further back in the map than in the photo. This may be down to the perspective of the photo, or possibly an error with the map

(Map ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“)

The area in the 1948 photo consisted of a number of wharves, as can be seen in the above map.

The land between the flats and the river was Ordnance Wharf. I cannot find the use of the wharf immediately before the war and subsequent bomb damage, however the type of industry that occupied Ordnance Wharf can be seen in the following newspaper article from April 1883:

“DESTRUCTIVE FIRE IN ROTHERHITHE – At about midnight, a fire, which was attended with the most disastrous consequences, broke out in the extensive oil-cake mills at Ordnance Wharf, Rotherhithe, London, S.E. The premises, which consisted of six buildings, each of three floors were occupied by a French firm, Messrs Francoise and Joseph Badart Freres, who carry on a large business as oil-cake merchants in the south-east districts.

How the fire originated remains a mystery, but in a very few minutes it gained a complete mastery of the buildings, enveloping them in a mass of flame which made it quite impossible for even the firemen who were first on the spot to attempt to effect an entrance.”

The entire site was destroyed in a couple of hours, and the fire burnt until six in the evening, and a large number of men then had to be employed to keep the site damped down so fires would not restart.

Oil cake seems to have been the product made from the oil released from many different types of seeds.

The book London Wharves and Docks, published in 1953 by Commercial Motor does not have an entry for Ordnance Wharf, so I assume it remained derelict after the war.

The next Wharf is Sunderland Wharf, the area to the right of the tall, narrow buildings and up to the chimneys. In 1953, the occupier of the wharf was listed as Bermondsey Borough Council, and use of the wharf was listed as “Disposal of house and trade refuse by barge”.

The location of the chimneys, and the building to the right, most of which is not shown in the photo was Upper Ordnance Wharf. In 1953 this was still a working industrial site, and was occupied by H.J. Enthoven and Sons, Ltd, who processed non-ferrous metals, coal, coke and iron ore, and seem to have been mainly processing the metal lead.

An extract from part of my father’s 1948 photo shows some of the infrastructure at Upper Ordnance Wharf. These look as if they were used to funnel materials from the factory site down into barges on the foreshore:

A highly industrial site, along with a number of derelict areas after wartime damage.

it is very different today, as I found with a walk around the site.

This is Rotherhithe Street, with the blocks of flats on the left. The block in the 1948 photo is the one furthest on the left:

The block of flats seen in the 1948 photo, and which enable the location to be identified is shown in the photo below. The distinctive middle section, where brick rises up above the entrance to the flats, the full height up above the upper attic space, which gives the central section a top of a flat wall of brick:

The estate of which the above block is part is Acorn Walk. Built in the 1930s, the estate consists of a number of similar blocks of flats as shown in the following estate map. The block in the 1948 photo is the block at upper right:

The name Acorn Walk comes from Upper Acorn Yard, a flat space for storing timber on which part of the estate was built, and Acorn Pond, an expanse of water a short distance to the south which was also used for storing timber.

Walking up to the river’s edge, and this is the view along what was Ordnance Wharf. The tall narrow building in my father’s 1948 photo was where the taller section of the terrace of houses, the one with the structure on the roof with cupola and weather vane, can be seen:

At the end of the above terrace is the following view, where Sunderland Wharf and then Upper Ordnance Wharf. and the H.J. Enthoven industrial premises were located. The funnels in the extract from the photo that tipped material down into barges were were the furthest trees on the right can be seen:

I had walked along the river walkway earlier in the year for the post on Horn Stairs, not realising that this was the location of one of my father’s photo. The following photo is looking back towards the warehouses of Canada Wharf taken from the edge of the 1948 photo, so these warehouse would have been to the left or east of Ordnance Wharf:

Horn Stairs is at the base of the Canada Wharf warehouse, the bottom left corner of the building in the above photo, so I went to take a look at the stairs.

I remarked in my post back in February, on the poor condition of the stairs, and how the upper steps seemed to be deteriorating badly, and just under six months later, the top step has disappeared, leaving a gap between the concrete edge of the walkway and the stairs, and the next couple of steps do not look all that robust.

The tide had been coming in for a few hours when I visited, so the foreshore was covered, and the navigation marker at the end of the causeway leading out from the stairs was isolated in the waters of the river:

To show just how wide is the range of the tide along the river, compare the above photo with the following photo taken for my Horn Stairs post which shows the navigation marker at low tide, with the remains of the causeway fully exposed, and the above photo had not yet reached high tide, and it was not one of the occasional very high tides.

Rotherhithe is really fascinating, and I will be writing more blog posts about the area in the coming months. To get from the north side of the river where I had taken the comparison photos from across the river, to the Rotherhithe side, I used the Thames Clipper / Uber boat route RB4, which is a dedicated route between Canary Wharf and the Doubletree Hotel in Rotherhithe.

This is a brilliant route across the river, and lands at the Doubletree Hotel where as far I can tell, the route to the street is through the hotel lobby (or at least that is the route I have always taken).

The following photos cover the short section of street from the Doubletree Hotel to the site of the 1948 photo, starting with this view looking along Rotherhithe Street:

The first building is this rather ornate house, which dates from the mid 18th century, and is not the type of building you would expect to find with so much industry between the street and river:

This is Nelson House and the building is Grade II* listed, and was a shipbuilder’s house. It reflects a time when this part of the river was not end to end industrialisation, but was small industry associated with the river, such as timber yards and shipbuilders, along with their owners and workers homes, including those who made good money from their river businesses. Inland from Rotherhithe Street when the house was built, it was all still fields.

The house was included in the 1972 Architects’ Journal feature “New Deal for East London”, on the possible threats to many of the historic buildings of east London (both north and south of the river. See this post for more information on the 1972 article).

The following photo shows the house in the early 1970s, with the name of the last Thames focused business to occupy the building:

Next along Rotherhithe Street are the buildings of Mills & Knight at Nelson Dock:

Nelson Dock had long been a slipway into the river and there was also a dry dock where ships could be taken in from the river, the water drained out, allowing the hull to be worked on in the dry.

The 1953 London Wharves and Docks publication still lists the site as providing these services.

We then come to the Blacksmiths Arm:

There may have been a pub here in the late 18th century, but the first written reference to the Blacksmiths Arms that I can find is from the London Morning Advertiser on the 2nd of May, 1823, when particulars for an estate that was for sale could be had at the Blacksmiths Arms, Cuckolds Point.

Given that Cuckholds Point was the area of foreshore at the base of Horn Stairs, I suspect that this is the same pub.

The current building dates from the mid to late 19th century, and the interior and the mock Tudor frontage dates from the 1930s.

We then come to the part of Canada Wharf that faces onto Rotherhithe Street:

Along this stretch of Rotherhithe Street is an unusual reminder of one of the earlier attempts at providing a river boat service – a reminder of some London transport history:

The White Horse company ran a ferry along the river from Canary Wharf and Rotherhithe to the City, opening in June 1999. In 2000, they also ran the ferry service from Greenwich, by the Cutty Sark, to the Millennium Dome.

Both services closed in 2001, and the assets of the company were put up for sale, so the above sign represents a ferry service that ran for two short years.

I am pleased I found the location of the 1948 photo, one of those I thought might be a challenge, and a photo that highlights just how much Rotherhithe has changed.

Now for some extra content after a walk through the City last week:

A Transformation for All Hallows Staining

Walking through the City last week and although I knew there was a major redevelopment planned, the sight of the church tower standing alone in the rubble of the demolished buildings that once surrounded the tower was rather stunning:

The construction site is surrounded by tall wooden hoardings that you cannot see over, however holding my camera above the wooden wall, and lots of random clicking revealed the following scene, where the area around the tower has been demolished down to ground level, revealing the basements of the demolished buildings:

The site was the home to the post-war version of Clothworkers Hall, and the Clothworkers’ Company have had a hall on the site since 1528. The Clothworkers’ Company also own the land and will have a new hall built as part of the overall redevelopment.

The documentation that goes with the development (called 50 Fenchurch Street) states that it sits on the “southern edge of the City’s eastern tower cluster”, and this can be seen in the following photo:

As well as a new hall for the Clothworkers’ Company, the development will consist of a 36 storey commercial tower, which will have a new public roof garden, which seems mandatory in recent City developments.

The tower will have “Innovative vertical urban greening to mitigate air and noise pollution, and improve biodiversity”, and there will be a new public realm at ground level, which will include access to the church tower and to the crypt of Lamb’s Chapel, which was originally at Monkwell Street, now under the Barbican Development (I wrote about Lamb’s Chapel in this post).

The view of the tower and building site from Mark Lane:

And from Fenchurch Street, where a lone pillar from one of the demolished buildings remains:

Whilst the buildings that were demolished were of no real architectural or historical interest, and the Clothworkers’ Company will remain on a site they have occupied for hundreds of years in the latest iteration of their hall, what is often ignored and lost is the historical layout of the streets and alleys.

In the following extract from Rocque’s 1746 map of London, I have highlighted the church (red arrow), Clothworkers’ Hall (green arrow) and an alley by the name of Star Alley (red arrow):

Although surrounded by post-war buildings, Star Alley, as a physical alley that you could walk, existed all the way up to the recent demolition, in the same alignment as in the 1746 map.

It may survive in some form in the new development, either studs on the ground, different types of paving, or a name of a walkway through the new tower, but the alley will have been lost, and for me, it is the loss of this historic streetscape which is worse than the loss of the post-war buildings or the build of a new tower.

I finished off my 2018 post with the following paragraph:

“It is remarkable that the tower of All Hallows Staining has survived for so long without a functioning church. The tower, churchyard, Star Alley, Dunster Court and the Clothworkers’ Hall form a small City landscape that is the same as mapped in 1746 and may date back to around 1456 when the Shearmen (the predecessors of the Clothworkers’ Company) purchased the land in Mincing Lane.”

Little did I know that six years later, apart from the tower of All Hallows Staining, everything else would be gone.

Sunderland Wharf and Ordnance Wharf, and All Hallows Staining – just two examples of just how much London changes over time.

The contrast between your 2018 post and now shows just how important your work is – thank you for continuing to document the changing face of London.

I totally agree

I am sorry indeed that Star Alley is no more, it was a jolly little cut-through and the buildings around it had proportion and a post-war elegance. The day that they decide to remove Minster Court, however, I will give a resounding cheer. It has long been top of my hit list of truly ugly buildings in London, more like an escapee from Gotham City than anything related to a minster. As for the Rotherhithe walk, I have done that myself a few times and always found it fascinating plus, if you get tired, there is a handy bus route that will take you westward. The Blacksmiths Arms is a pub I haven’t visited but always wanted to. On the list.

I do share your sadness – although not hugely distinctive, the 1950s building on the corner of Mincing Lane and Fenchurch Street was handsome and elegant. I cannot imagine I will appreciate what replaces it.

I do find Minister Court quite visually fascinating – and I think London would actually be worse without it – but part of its attraction is its uniqueness. Long may that endure!

Fascinating articles. Thank you for your research and diligence in updating previous posts.

1. I’m interested in Nelson house and Nelson docks given my interest in Lord Admiral Nelson of late 18th century. Is there a connection with him, the admiralty, or was this a private business of shipbuilding and docks of the time?

2. It is interesting to reflect on the driving forces changing industry and commercial shipping after your father’s 1948 images. A big change during WWII was the use of containers and roll on roll off technology which I assume required a deep harbours and infrastructure on a larger scale. London docks, commerce, and shipping became redundant with industry moving nearer deep harbour ports. Also increased lorry and road transport probably influenced this concentration of shipping at fewer locations (Immingham & Grimsby and Felixstowe are tops with maybe 6 other locations) but Port of London is still active but I do not really know much about its current location or operations.

If the flats at Ordnance Wharf were built today, I assume a study of the soil would first be in order, to establish if there are dangerous materials that might affect the tenants’ health long-term. Do you suppose any such due diligence was required of developers before the flats were constucted?

A little clarification.

Regarding the newspaper article about the Ordnance Wharf fire in 1883,

Oil cake was the residue from pressing oil seeds (groundnuts/peanuts linseed etc). When the oils had been pressed from the seeds the “cake” still contained some oil so was highly flammable. One use for the cake was in cattle feed mainly for the protein content although the energy content via the residual oil was also significant. There used to be an animal feed manufacturer known as B.O.C.M. (British oil and cake mills) that used the cake to add to cereal when compounding cattle feeds.

If you do more on Rotherhithe please do an article on the Surrey Docks Farm. It has a fascinating history which you can see on text boards in the farm.

Also the Knights Dry Dock at the Hilton is proposed to be used for the new ferry link across to Isle of Dogs

I imagine the oil seed cake mills were originally developed with the vast horse population of London in mind as well as the dairy herds in surrounding areas.

Although further research suggests it was not used as cattle food until the early 20th Century.

I’m off down the rabbit hole

Another very interesting and enjoyable post. One question you may be able to answer, relating to the second half of the post about All Hallows Staning. Who is moving into all these new (and mainly) taller developments? I would have thought that with today’s technology coupled with the effects of COVID would mean we need less office space. This does not seem to be the case! However the company my son has been working for never went back to five day working after Covid and only expect attendance of about 2 days a week. I can only assume they are an exception – although my sone reassures me they are not.

Are you planning on doing a walk here David? It would be fascinating if you did. I mentioned to you once that this place is close to my heart, my family lived around Rotherhithe, last address was Trident Street but many years ago. As always absolutely excellent post, I can’t imagine the hours you put into research, I’m going to have several reads to try and take it all in. I’m extremely grateful to you for what you do and I know fellow readers feel the same.

Paul M. (Lincoln)

Another enthralling post . I thank you from my kitchen in country Victoria, Australia , on the morning of our King’s Birthday Weekend public holiday . We have celebrated the birthday of the British Monarch , also our Australian Head of State , on the second Monday in June since the time of George V1 . We spent a month in London last year mostly around this part of the Thames and further downstream . It’s an area I hadn’t visited in over 40 years . What changes . I do love reading your emails as they provide me with plenty of inspiration for yet another visit next years . Cheers …Paul Huckett

Fascinating to see how this beguiling area was once a scene of intense – polluting – industry. It’s great that you’re documenting these major transformations which, otherwise, would be largely forgotten. Looking forward to discovering more on your Limehouse ‘Iniquity’ walk on Sunday.

Thanks for another fascinating post. My great grandfather was, between 1891 to 1914, foreman at the Union Oil & Cake Mill – shown at Sunderland Wharf on the 1894 OS map. Brace’s History of Seed Crushing lists the mill as being erected in 1874 by Badert Brothers, (who, not surprisingly, went bust in 1885), and then taken over by Union Cake Oil in 1886.