London has always changed. Buildings have been constructed then demolished. New streets built, others widened and some built over and lost. Individual building plots have been consolidated and replaced with much larger buildings. As well as covering larger plots of land, buildings across the city have also grown taller, although it is only in the last few decades that the city has become home to a growing number of very tall towers.

London has always been a city where you can walk down a street after a space of a few months, and find a familiar building demolished, with a new building, frequently of a very different design and materials, being constructed on the same site.

Patterns of ownership change, ways of working change, new space is needed, older buildings become expensive to maintain, planning regulations change, new materials make very different designs possible and architectural styles change.

London has been through two major reconstructions caused by very tragic events. The need to rebuild after the 1666 Great Fire of London, and again after the bombing of the Second World War.

But there is also continuous change, and this has long fascinated anyone who has lived, worked, or just visited London, and there have been many approaches to documenting this change.

One such approach is the book “London Rebuilt, 1897 – 1927” by Harold Clunn and published in 1927.

The book documents the changing city over a period of thirty years from 1897 to 1927. In many ways this is an arbitrary period of time, and the author admits that he was aiming for the first three decades of the 20th century, however there were so many changes at the end of the 19th century that the last three years of the previous century were taken into the account.

The book could have begun much earlier, as the 19th century was a period of extensive change, with the Victorian transformation of London responding to the city’s growth as a world city, exponential increase in trade, commerce, industry and population, and Victorian attempts to improve living conditions, sanitation, traffic routes and roads, along with the introduction of new utilities such as gas and electricity.

But again, London is always changing, so a book covering any period would always be an arbitrary choice of dates.

The book consists of chapters focussing on different areas across the wider city, and each chapter includes a written description along with a number of photos, many showing before and after views.

As well as the physical aspect of the city, there are other changes.

The way people dress, the number of people on the streets, traffic, the gradual change from horse drawn transport to the use of the motor vehicles.

Clunn’s book provides a fascinating glimpse into London in the first decades of the 20th century.

In many ways, streets that we would easily recognise today, but also streets that have changed dramatically in the past 100 years.

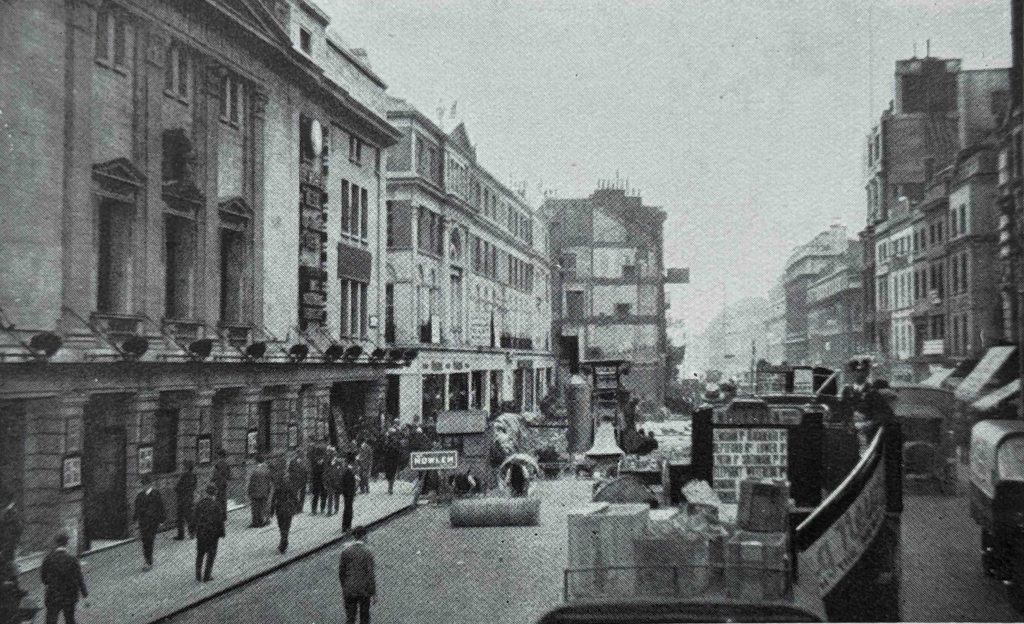

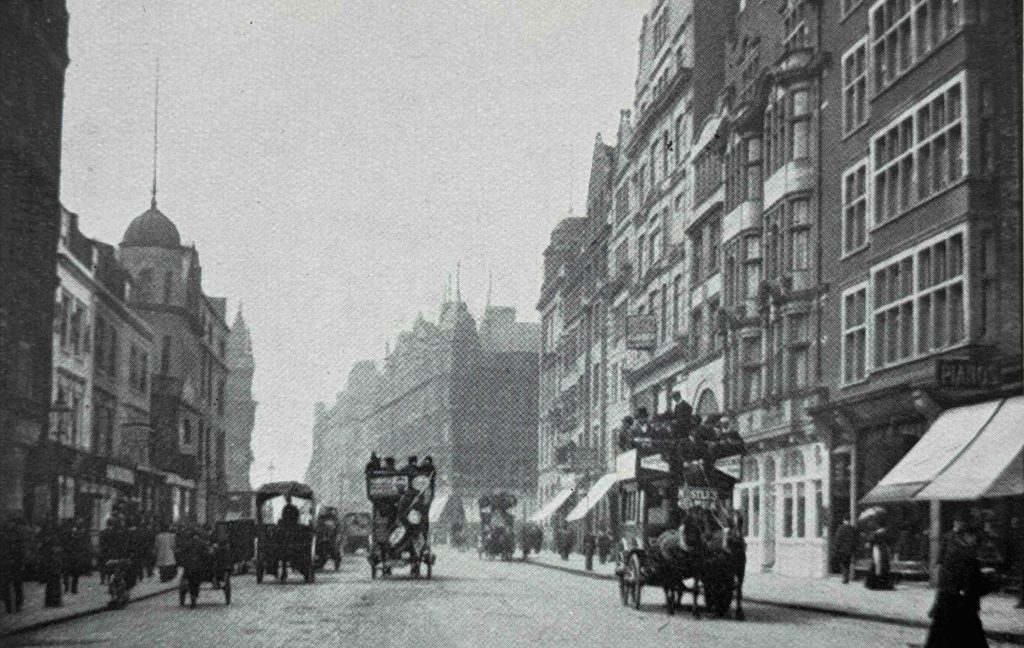

So in this post, we will travel back to the early years of the 20th century and explore the streets of the city, starting with Finsbury Pavement as it appeared in 1901 before the start of reconstruction:

Finsbury Pavement was the street that ran to the west of Finsbury Circus, between London Wall and Ropemaker Street. A large block of land to the west of Finsbury Pavement was demolished and rebuilt, and this work included upgraded entrances to Moorgate Station.

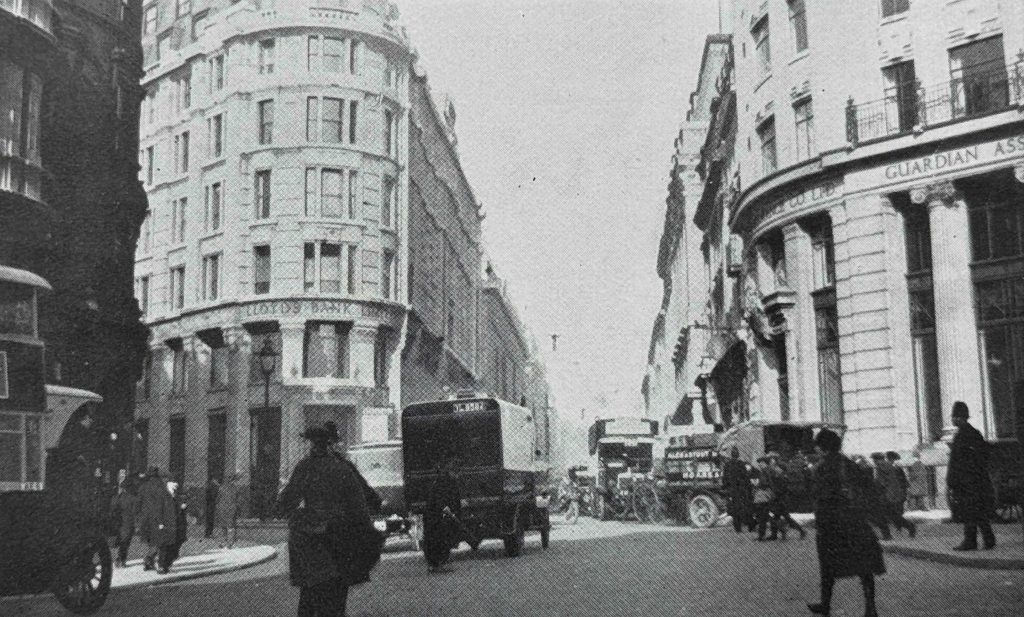

Today, Finsbury Pavement is known as Moorgate. The following photo is from the mid 1920s and shows the street rebuilt, and new entrances to Moorgate Station can be seen to the left and right:

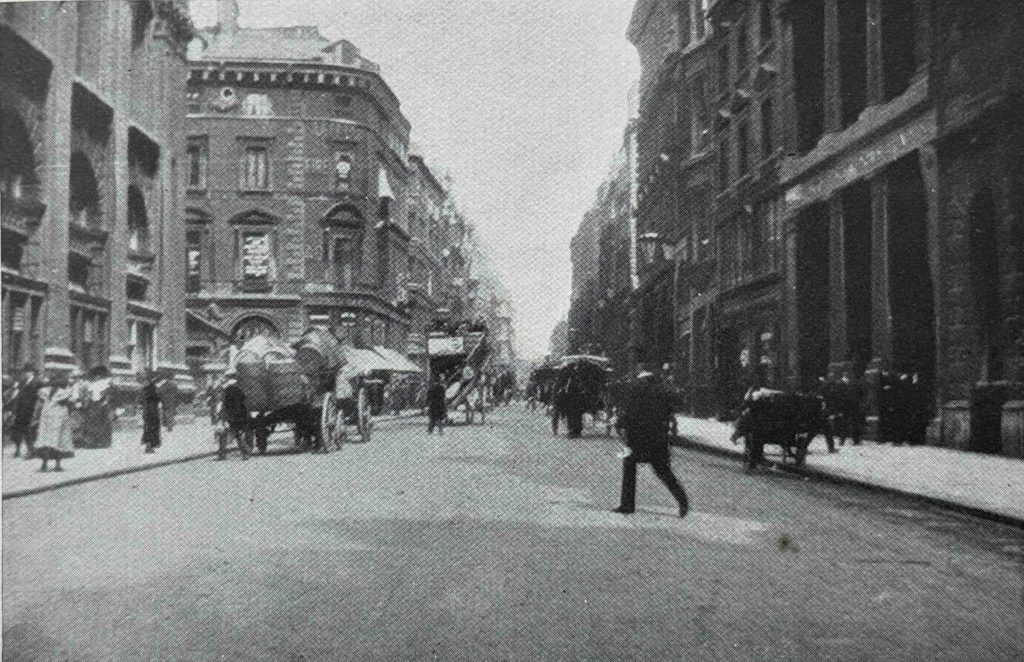

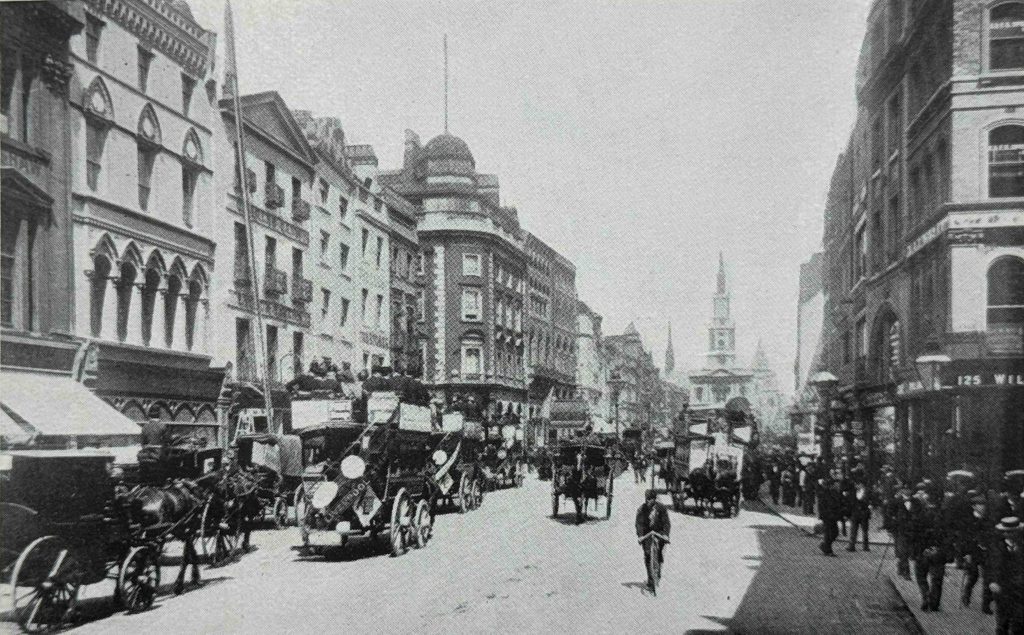

This is King William Street around 1890:

The rebuilt King William Street shows how buildings were increasing in height amd becoming more imposing. We can also see the start of the transformation of vehicles types with horse drawn in the above photo and just over 30 years later, a motor driven lorry van be seen in the foreground:

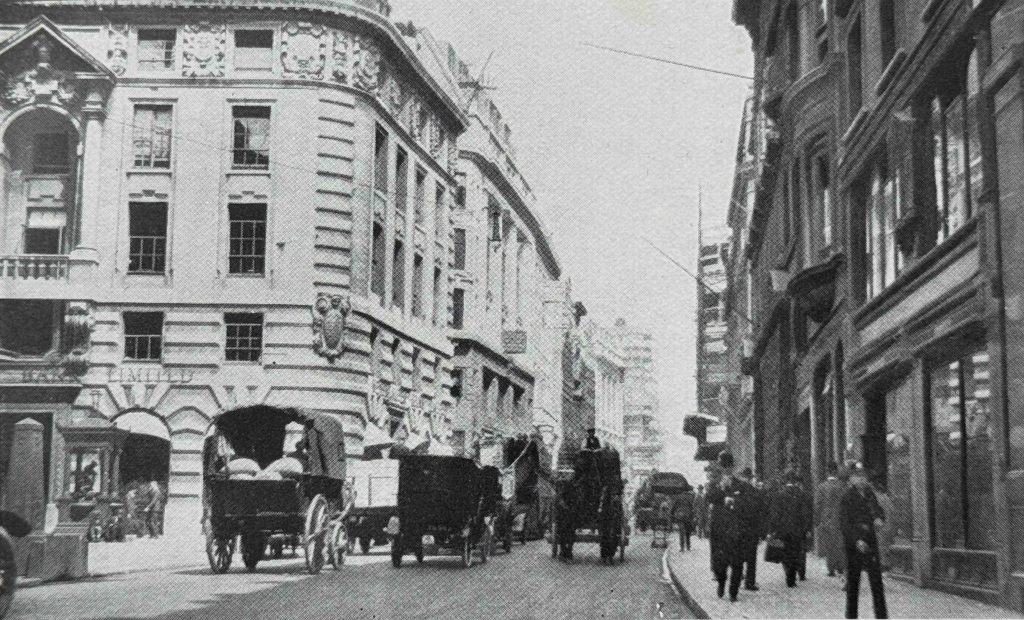

This is a 1901 view along Cornhill from the Royal Exchange:

Twenty five years later, Cornhill is still a busy street with a number of buildings of recent construction, made obvious by their clean appearance. Not yet darkened by the smoke of the city:

Many of the photos in the book appear to have been taken from the top of the open top buses that carried Londoners along the street. The following image is one example, and is looking along Fleet Street from Ludgate Circus:

Just to the right of centre can be seen one of the new electric street lights. I wrote about the introduction of these into Tottenham Court Road in a previous post, here.

As well as the replacement of individual buildings, the late 19th and early 20th century saw large areas of London completely rebuilt. One of these was around Kingsway and Aldwych, and the following photo shows a large open space where the construction of Kingsway was underway in 1904:

Little details in these photos help to add to the character of London at the time. To the left of the above photo is a painted sign on the end of a building wall for the “Army Men’s Social Work Shelter”.

It is hard to make out the words at the top and bottom of the text on the building, but I think the word at the top is Salvation, as this building was probably one of the many Salvation Army Men’s Social Work Shelters across London, and indeed across the major cities of the country.

These institutions provided cheap overnight lodgings and food for the homeless, and in 1900, over 4,000 men were taken in nightly from the streets. Each person had to pay a charge of one penny, so it was not an absolute charity, and the Salvation Army established a three stage work programme, which had a very questionable outcome.

Stage one was work and accommodation in their city institutions. Stage two was their transfer out to the Salvation Army farm in Hadleigh, Essex for “outdoor work”, and stage three was their transfer to an overseas colony.

Hadleigh Farm is still run by the Salvation Army.

One wonders how voluntary this progression through the three stages was, particularly the transfer to an overseas colony.

The following photo is a 1920s photo of Kingsway, looking north from Aldwych. The book does not explain whether there is any relevance between the photo above and the photo below:

In the centre of the above photo can be seen the “LCC Tramway Station Entrance”:

The following photo is on a different page, but has the same title as the above photo “Kingsway, looking north from Aldwych”, but now with a date of 1906:

If they are of the same view, then there had been a remarkable transformation in thirty years. Kingsway was a new street, planned during the late Victorian period, along with other major road schemes such as New Oxford Street and Shaftsbury Avenue, with an aim to relieve the growing amount of traffic congestion across the City.

The above photo also shows an entrance to the tramway station.

It was not just streets and buildings that were redeveloped. The following photo shows the reinstatement of the lake in St. James’s Park:

The reason for the reinstatement was that after the outbreak of the First World War, the lake in St. James’s Park was dried out, and a series of temporary buildings erected in the site, presumably in someway connected with the war effort.

In 1922 the huts were demolished and the lake was restored, however the lake had been left dry for so long that many of the repairs were inadequate, water started leaking out, and the lake almost completely dried up again.

More repairs were made, the lake refilled and restored to become the familiar part of the park that it had been.

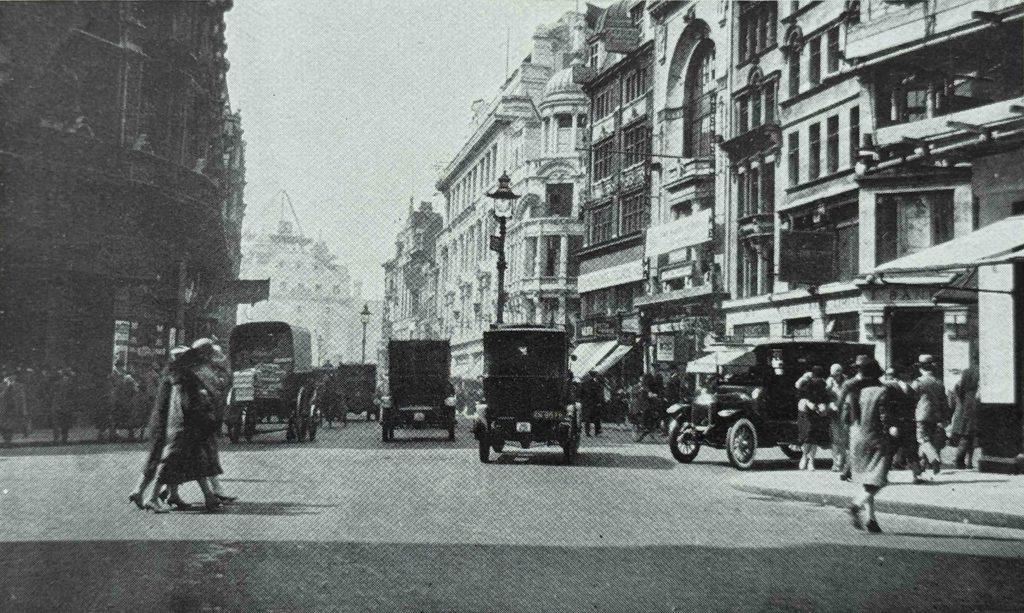

This is the “old” Strand, looking east from Southampton Street:

And the “new” Strand, again looking east from Southampton Street:

The above two photos again show the transformation of traffic from horse drawn to motor, and we can also see how smaller plots of land were being converted into larger plots for larger buildings.

The two photos above seem to be of the same view, as the church steeple can be seen at the end of the street, although it is very faint in the above photo.

The following photo has the title “The Old Tivoli Theatre, demolished in 1914”, and is a view along the Strand, with the Adelphi theatre on the right and Adam Street on the left:

And the following photo shows the “New Tivoli Cinema and the widened Strand, looking west”:

The Tivoli Cinema is the building on the left of the photo. It opened on the 6th September 1923 with music hall artiste Little Tich, so despite the book calling it a cinema, it was also continuing to operate as a theatre.

The demolition and new build of the Tivoli was part of the scheme to widen the Strand, and the end of another building which will soon be demolished as part of this scheme can be seen further along the street.

The Tivoli was closed on the 29th September 1956, demolished and a new Peter Robinson store built on the site, which in turn was demolished in the late 1990s, with the office block we see today then being built on the site.

In the above photo, the building to the right of the Tivoli, on the left of the street, the building with the arch above the second floor remains to this day.

Staying in the Strand, this is the “Old Strand, looking east from Savoy Street”:

The same view in the 1920s:

It is interesting how new builds often retain features from the previous building on the site, for example the dome on the top of the corner building on the left in the above two photos.

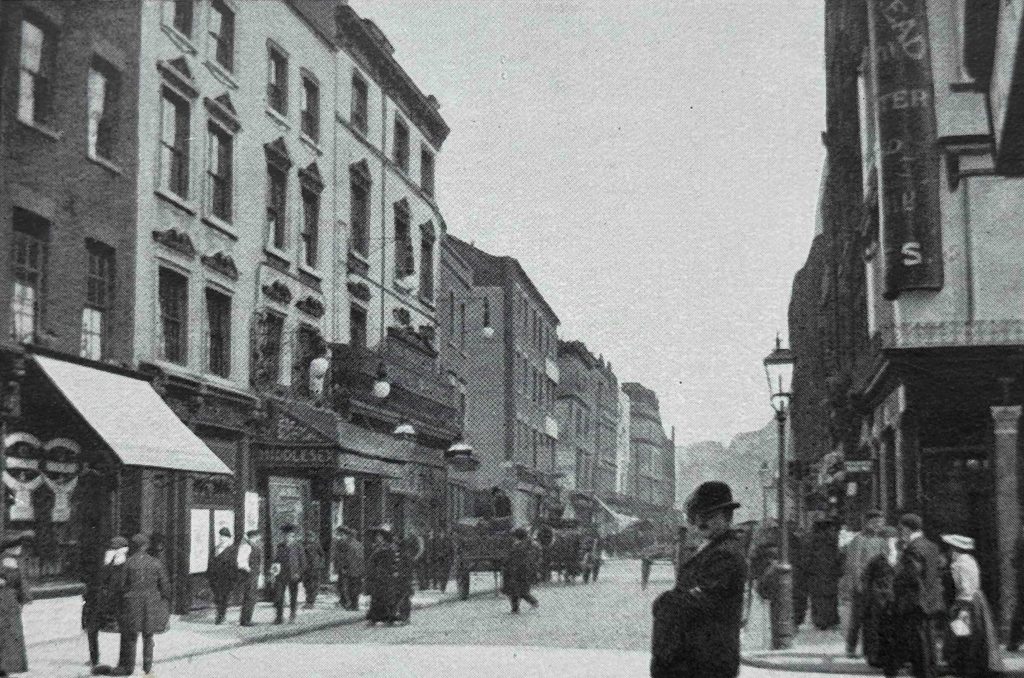

Another soon to be demolished entertainment building was the old Middlesex Music Hall in Drury Lane, shown on the left of the following photo:

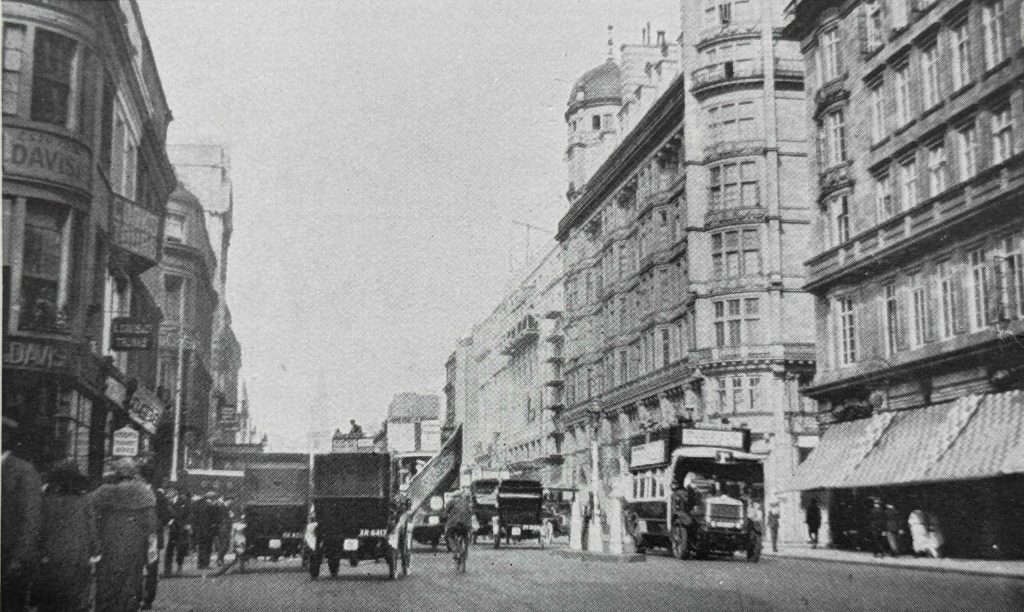

Old High Holborn, looking east from Southampton Row:

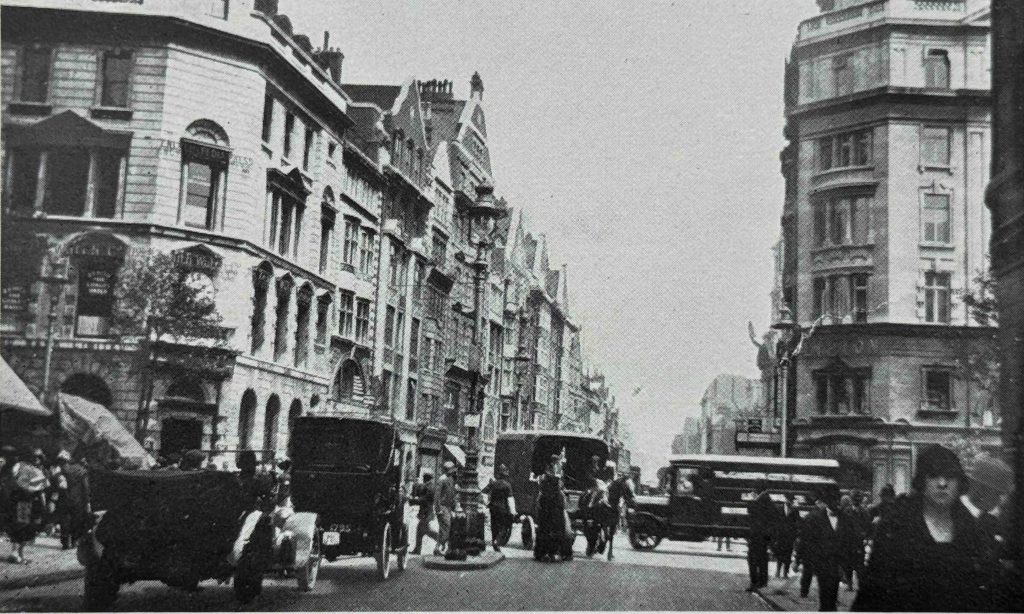

New High Holborn, again looking east from Southampton Row:

There is a single horse drawn vehicle in the above photo, with the rest being motor vehicles, where in the “old” photo it was all horse drawn. Street lighting has also changed from smaller lights on the side of the pavements, to taller lights in the centre of the street, and again, the later buildings are of a more substantial build.

Many of the rebuilding works were aimed at improving traffic flow across London. Many streets still had what were described as bottle necks, where the width of the street would reduce, and many works of the late 19th early 20th century were aimed at eliminating these.

The following photo shows the “High Holborn Bottleneck”:

The “Oxford Street Bottleneck Near Tottenham Court Road”:

The following photo is titled “Charing Cross in 1904, prior to the construction of the Admiralty Archway”:

And then “The New Admiralty Archway, Charing Cross”:

There do appear to be a number of errors in the labelling of some of the photos in the book, so I am not sure how much either Harold Clunn, or his editor checked. In the above two photos, the first is labelled “Charing Cross in 1904, prior to the construction of the Admiralty Archway”, and the reference to Admiralty Archway implies that the archway would be built somewhere in the scene in the old photo, however the “prior” photo is looking down Whitehall (the buildings on the left are still there), the photo is not looking down the Mall, which is the location of the Admiralty Archway.

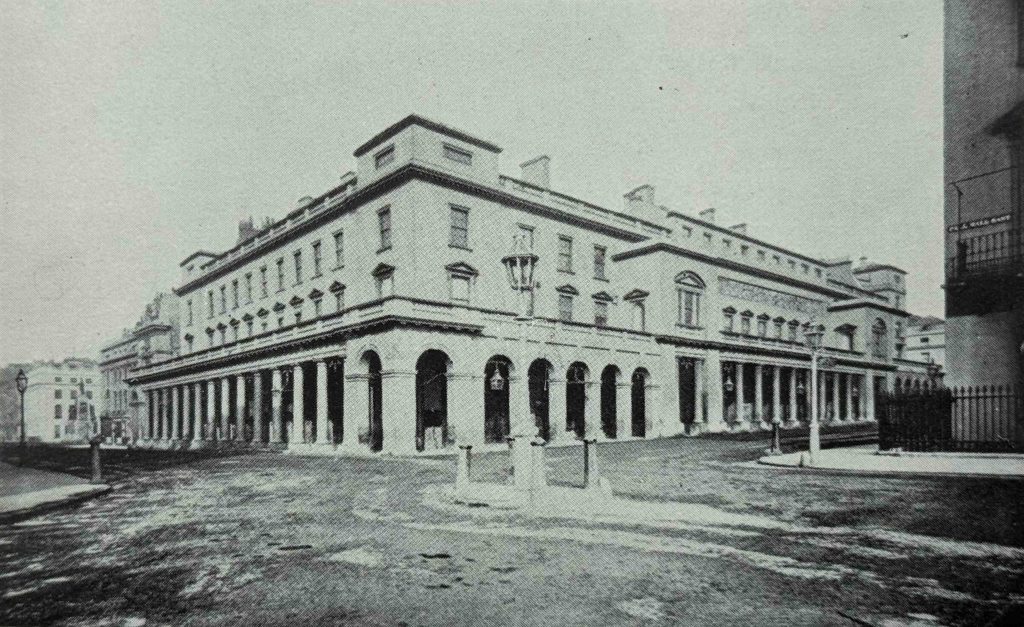

The following photo is much earlier than the date range in the book’s title of 1897 to 1927. This is the old His / Her Majesty’s Theatre on the corner of Haymarket and Pall Mall, which had been destroyed by fire in December 1867, so the photo must be from 1867 or earlier:

The fire was significant, with the Illustrated London News reporting on the fire on the 14th of December 1867 that “The spacious and beautiful opera house at the corner of Haymarket and Pall Mall, called Her Majesty’s Theatre, and formerly the King’s Theatre, was entirely destroyed, in less than an hour, by a fire which broke out on Friday night about eleven o’clock”.

The His / Her Majesty’s Theatre dated from 1791, and was the second theatre to have been built on the site. It occupied a large plot of land. After the fire, the remaining walls were demolished, and the new His Majesty’s Theatre that we see today was built, but only on part of the plot of the old theatre.

For some of these photos, I did get a chance to do a photo of the site today, to show a Then and Now comparison.

The following photo shows the site of the original His Majesty’s Theatre as it appears today:

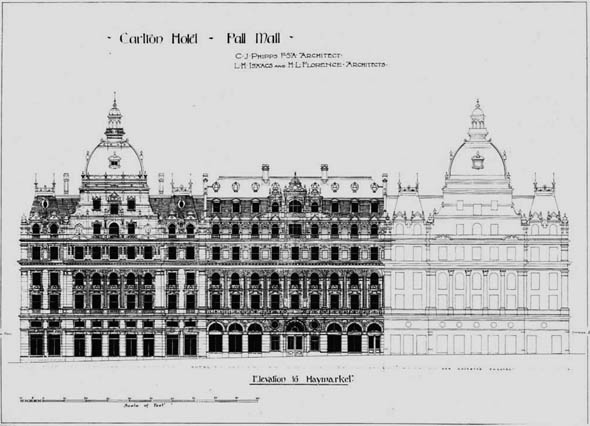

To the left of the new version of the theatre (which can be seen to the right of the glass fronted building), the Carlton Hotel was built. The following drawing shows the elevation of the hotel facing onto Haymarket, with the rebuilt His Majesty’s Theatre in outline on the right (which can still be seen in the above photo):

Attribution: Charles J. Phipps (1835–1897), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The hotel suffered bomb damage during the last war. It was later demolished, and New Zealand House, which remains to this day, was built on the site – the glass fronted lower floors and tower.

The following photo shows the “Carlton Hotel and the Kinnaird House, Haymarket and Pall Mall”:

The above photo was taken in Cockspur Street, just after leaving Trafalgar Square. The building on the left is still there, as is the second building on the right. The Carlton Hotel is the building in the middle, furthest from the photographer, and the large dome on the roof is the same as that shown in the plan for the hotel.

In the following photo of roughly the same view today, the building on the left, covered in scaffolding, with an image of the building along the front, is the ornate building on the left in the above photo. The tower block in the background is where the Carlton Hotel was located:

In the following photo we are still in the Haymarket, and the view shows the “Haymarket, looking north showing the Capitol Cinema and Haymarket Hotel”:

The photo was taken a short way down Haymarket, and the first street leading off to the left is St. James’s Market. It is from the 1920s as we can now see a large number of motor vehicles in the street.

The Capitol Cinema was formerly named the Capitol Theatre, and opened on the 11th of February 1925, so just before the book was published.

The Capitol had a relatively short life as in 1936, most of the theatre was demolished, and reconstructed as the Gaumont Theatre, which in turn was significantly rebuilt in 1959, reopening as the Odeon, Haymarket in the basement of an office block. The Odeon closed in 2000, but the office block still remains on the site.

The building at the far end of the street, with the triangular shaped top to the façade is still there in Coventry Street, and the ground floor now houses a Five Guys, the following photo shows the same view today, with the old Capitol theatre building on the left, and the triangular shaped upper floor building at the end of the street:

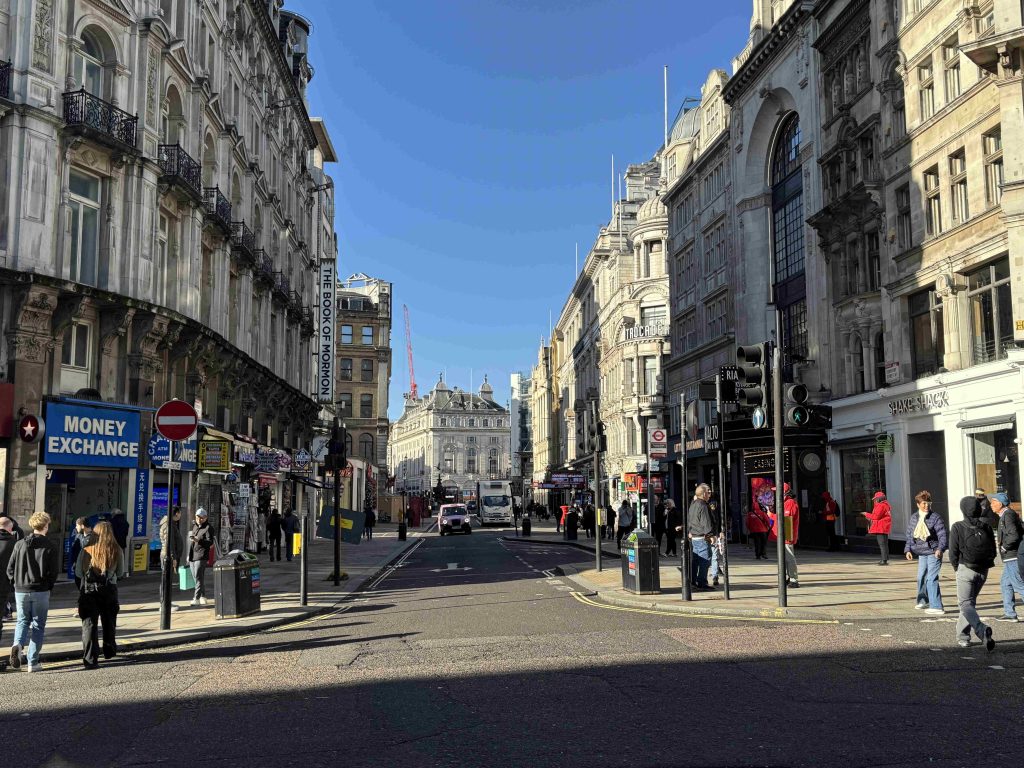

And heading up to Coventry Street, this is Coventry Street in 1904, looking west:

In the above photo there is a sign for “Wales” on the left, and this is the Prince of Wales Theatre, so the street on the right is Rupert Street and Piccadilly Circus is in the distance.

The following photo is of the same view, but I think was taken further back towards Leicester Square, as the building with the arch on the façade is still there today and is the Rialto:

In the 1904 photo of Coventry Street, on the right you can see some of the late 18th century houses surviving from the first stages of development of the area. These had been demolished by the 1920s, and replaced with the larger buildings, many of which survive today, including the building on the right with the dome on the corner just below the roofline, which is the Trocadero.

Also in the above two photos we see the transition from horse drawn vehicles to motor vehicles.

The following photo shows the same view today, with the arch of the Rialto still to be seen on the right:

These photos provide a brief example of how London has changed over the years.

We could step back into many of the 1920s photos, and instantly recognise the majority of the buildings. What has changed, and is not really visible in these photos, is the change in the businesses that occupy the street facing ground floor.

Just taking the above photo, today the majority of businesses on the ground floor are focused on the tourist trade, with restaurants, take-aways, foreign exchanges, the American Sweet Shops and Souvenir Shops that pop up and disappear rapidly across so much of the West End of the city.

London Rebuilt focused on three specific decades, starting at the end of the 19th century, and up to the late 1920s, however, as discussed at the start of the post, change in London is continuous, and any book, blog post, photo etc. will only show a snapshot of the city at a specific time.

In just a few years, the view can change dramatically, and that is the only thing which is certain for any city such as London – there will always be change.

Kingsway was the ast of the big C19 street imppovements, driven through a slum and connecting the Strand with Holborn. It tool 25 years for the new builinds plots along it and Aldwych to be filled, most to design by Trehearnes who are still in Holborn today.

That work reveals the biggest architectural change in the period of the book – the replacment of Victorian and older blocks with much bigger Portland stone structures, easily visible in the aerial photos taken commercially at the time.

Hi just to be a little more specific here I met my wife on the night of that win in 1966. We met at the Empire ballroom Leicester Square which I believe is not there now. She used to work at Coutts Bank in the strand which has been demolished and rebuilt since then. As you say change in a city the size of London is ongoing and will probably never end. Just to look at your recent blogs highlights that. I enjoy your blogs as it keeps me updated on events in my old stomping ground, so thank you.

Very interesting to see the changes that the ‘turn of the century’ brought to many areas of London. I live in the shadow of the Lots Road power station (the powerhouse for London’s underground for over 90 years). During the 1960’s 2 of the, over, 250 foot chimneys were removed – however that considerable change is nothing when compared with the 2 huge tower blocks that now dwarf the power station chimneys. Locals objected to the height of the towers but were ignored by John Prescott who allowed their construction. Change in London is usually driven by investors and profit…

I enjoyed the topic and the prose. I wonder, and this is in no way meant as insult, if the preamble could have been one short paragraph or even sentence? The meat of the article took a while to arrive, and I read that part twice but very much skipped the first 5 paragraphs the second time. I mention it as much to point out it was worth the patience, I just wonder if it needed a 5 paragraph introduction? Perhaps other disagree.

In the first of the photos about Kingsway (the one with a bowler-hatted gent at the gates of a building site), in the distance is what seems to be a tall industrial chimney. Where on earth was that?

could it be the shot tower on the other side of the Thames?

I’m doubtful that the chimney can be the shot tower on the South Bank. The shot tower was south of Kingsway. The shadow of the bowler-hatted gent seems to imply that he had his back to the sun. If so, the chimney must have been in a direction that was in the northern half of the compass rather than the southern half.

Peter Bertoud’s second webpost on the Kingsway tram tunnel construction ~ https://www.peterberthoud.co.uk/post/forgotten-images-destruction-construction-in-aldwych-kingsway ~ has 2 photos relevant to this discussion.

One shows the chimney in close proximity to the worksite with this caption: “Central portion of Kingsway on August 3rd, 1905.”

The captions for the photo that follows is: “Kingsway – Same view as above on August 22nd, 1905 (showing chimney stack demolished).”

Geraldine,

Many thanks indeed for pointing me to that webpost. The first photo in the post shows that the chimney was at the end of Little Wild Street. The large scale OS map of the area (https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=19.0&lat=51.51533&lon=-0.11906&layers=188&b=osm&o=94) shows that the chimney must have been part of the Metropolitan Electric Supply Company’s Works in Sardinia Place.

Brilliant, thank you for sharing

The full wording is indeed “The Salvation Army Men’s Social Work Shelter For Homeless Men”, the hostel was at 9-10 Stanhope Street, pretty much where the tram station entrances are seen in the later photos.

What a fabulous piece of research. Absolutely brilliant. Thank you

Regarding the construction of Kingsway, Peter Bertoud’s webpost on the 1905 opening includes some fascinating graphics, including a map showing Kinsgway/Aldwych as an overlay on the streets around Clare Market & a set of pre-demolition photographs.

https://www.peterberthoud.co.uk/post/forgotten-images-before-aldwych-and-kingsway

As always, very interesting and informative. What a difference a few years makes, let alone a century!