The subject of this week’s blog was easy to find, however I found the specific location from where my father took the following photo through one single building remaining in an otherwise completely changed street scene. The church tower in the centre of the photo is that of St Botolph without Aldgate. The church tower is distinctive and easy to recognise, although the very top of the spire is missing, probably through bomb damage.

There are no other obvious locations in the photo to identify from where my father took the photo. There looks to be a bomb site between the church and the road.

I walked all the surrounding streets trying to find the location of the photo. The search was not helped by the amount of new building obscuring the view to the church, however when I walked down Dukes Place towards the junction with Creechurch Lane and Bevis Marks I saw one building that looked familiar.

If you look to the left of the above photo, there is a tall building. Look to the left of the photo below and the same building is remarkably still there – a lone survivor from the pre-war buildings in these streets.

Although the ground floor is very different, the floors above have the same architectural features in both photos. The building today is NMB House, however if the building is the same as described in the Pevsner guide to the City of London, it was Creechurch House.

NMB House is at 17 Bevis Marks, and the Pevsner Guide states:

“Nos. 17-18, Creechurch House: smart warehouse facing Creechurch Lane, by Lewis Solomon & Son, 1935, with metal faced floors between stone mullions.”

Pevsner states that the building included number 18. It looks as if the building has been reduced in width, with the space where number 18 once stood, now being occupied by a new building with only number 17 remaining from the original.

The following photo shows the building with Creechurch Lane running to the right,

This is a wider view, and my father took the original photo from just in front of the bus stop. Compared to the original street, post war widening and straightening can be clearly seen in the view today.

Walking down Dukes Place towards St Botolphs without Aldgate, the church becomes visible and at the rear of the church are trees, much as in my father’s original photo.

A much better view of the church can be found by walking a short distance down Minories, the street directly opposite the church.

As with many old City churches, the first written records that mention St Botolph without Aldgate date back to the 12th century, although an earlier Saxon church was probably on the site as evidence of 10th or 11th century burials have been found in the crypt.

The church was originally attached to the Priory of the Holy Trinity. It was rebuilt just before the dissolution of the monasteries during Henry VIII’s reign and restored in 1621. St Botolph without Aldgate was declared unsafe and demolished in 1739, making way for construction of the church we see today.

The church before demolition was recorded in a number of prints, including the following dated 1739:

The rebuilt St Botolph without Aldgate was designed by George Dance the Elder and built between 1741 and 1744. George Dance was the surveyor for the City of London and the designation ‘Elder’ is to separate this George Dance from his son, also George Dance who was also an architect for the City.

The new church was aligned so that the entrance to the church and the tower above faced directly to the Minories.

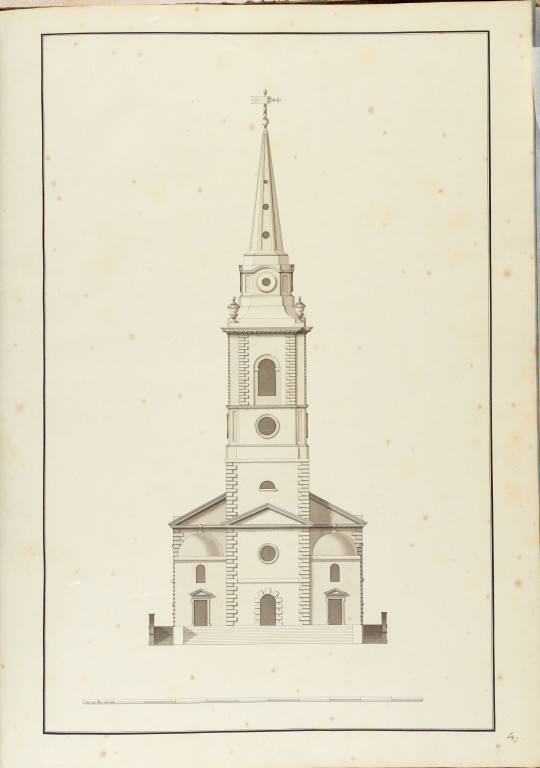

The following drawing by George Dance the Elder shows the church looking exactly the same as it does today:

The dedication of the church, St Botolph without Aldgate is firstly to St Botolph, who established a monastery somewhere in East Anglia in the 7th century. St Botolph died around the year 680. The addition of “without Aldgate” is to reference the location of the church as being outside the City walls.

There are a number of other St Botolph churches on the edges of the City, St Botolph without Bishopsgate, St Botolph without Aldersgate, and there was a St Botolph Billingsgate, destroyed in the Great Fire and not rebuilt.

I have found a couple of possible sources for the association of St Botolph with these churches on the edge of the City. The first is that in the 10th century, King Edgar had the remains of St Botolph divided and sent to locations through London. They passed through the City gates and the churches alongside the gates through which the remains passed were named after the saint.

The other reference associates the City gates with St Botolph being the patron saint of wayfarers, who would use the City gates as their entrance to and from the City.

Both of these sound plausible, and I find it fascinating that the names of churches on the edge of the City refer to both the original Roman wall and possible events from the 10th century.

A traveler arriving at the City gate near St Botolph without Aldgate would find a very different view today with the office towers of the City rising behind the church.

There is an open space on the City side of the church, however buildings run up close to the church to the north and east:

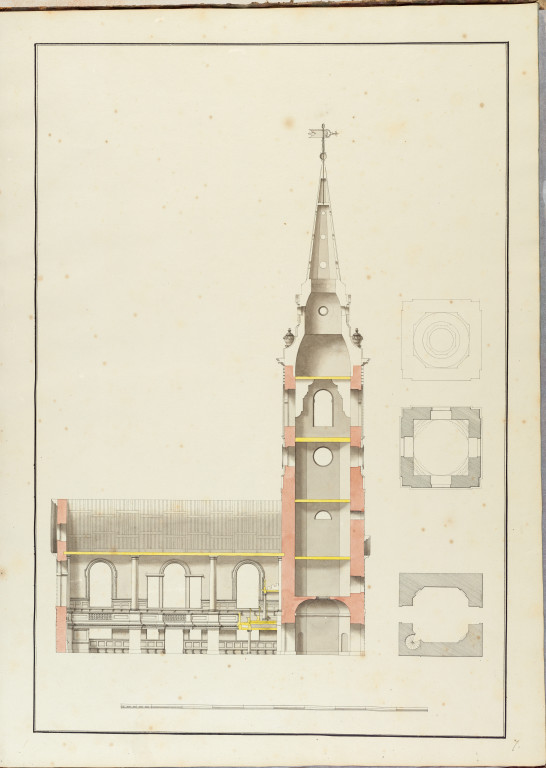

Another of the plans drawn by George Dance showing a section through the church:

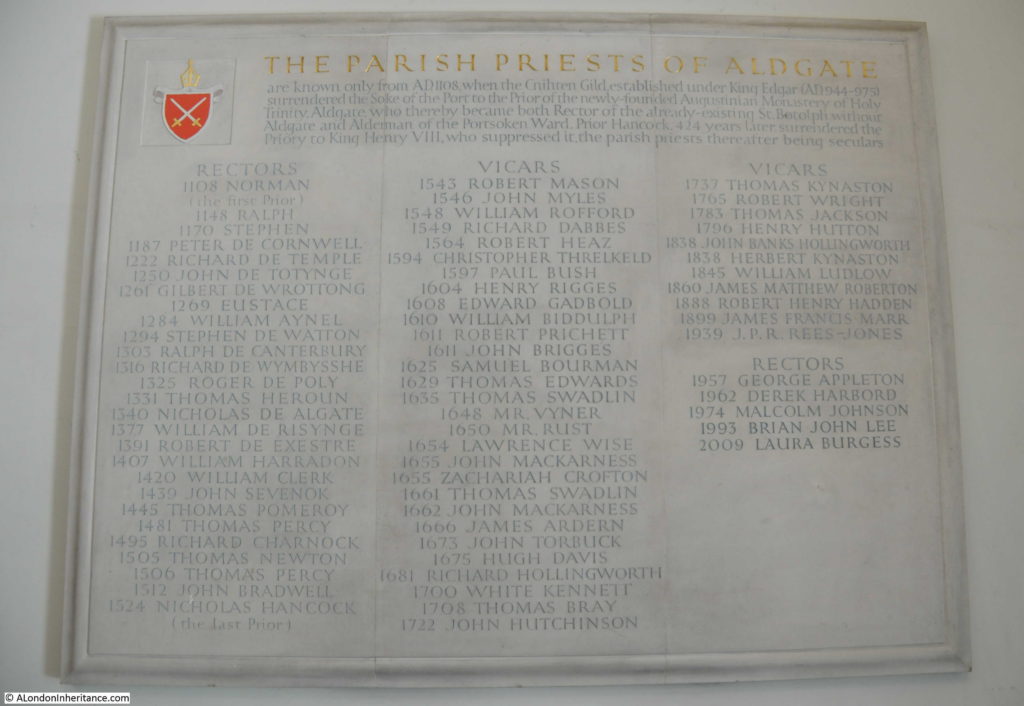

On entering the church there is a record of all the parish priests of the church. The first line almost appears apologetic for the lack of records remaining from before the 12th century “The parish priests of Aldgate are known only from AD 1108”

Also in the entrance to the church is this splendid momument to Robert Dow, who died in May 1612 at the age of 90 – a rather good age for the 17th century.

Robert Dow was a Master of the Merchant Taylors and during his life gave away a substantial sum to various charitable establishments. The value of his donations and those receiving the money are listed on his monument.

I am not sure what the symbolism of the hands covering the skull means – it gives the impression that he had a hold over death (as his 90 years possibly demonstrated), or perhaps representing his own skull in death.

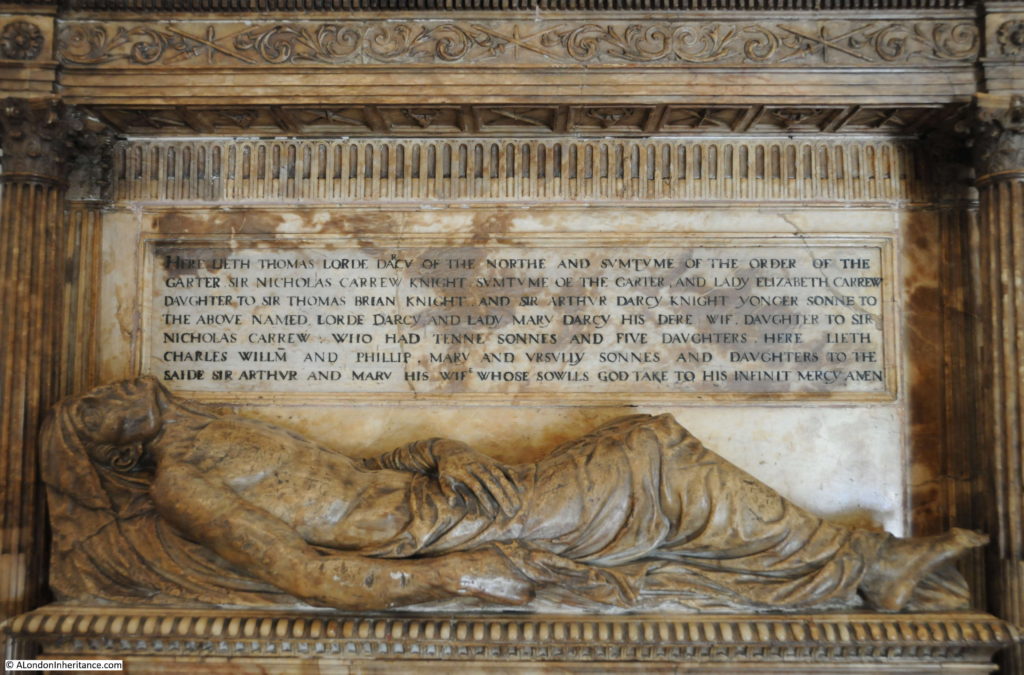

Another monument is to Thomas, Lord Darcy who was beheaded on Tower Hill for treason in 1537 during the reign of Henry VIII.

The view on entering the church:

The interior of St Botolph without Aldgate retains the original galleries and Tuscan columns, however much of the decoration is from a redecoration of the church carried out between 1888 and 1895 by J.F. Bentley who added some remarkable decorative plaster work to the ceiling of the church:

Close up of the ceiling decoration:

I find it fascinating to discover the stories behind the monuments in the City churches. In St Botolph without Aldgate there is a monument to Willian Symington, who died on the 22nd March 1831. The monument records that he constructed the Charlotte Dundas, the first steamboat fitted for practical use, also that he died “in want”.

William Symington was Scottish, having been born in the small village of Leadhills. He studied engineering at Edinburgh University and worked in Wanlockhead where his brother George was building steam engines to James Watt’s design.

William Symington was always interested in whether a steam engine could power a boat. The problem was not just the mechanism to propel the boat, but also how a steam engine could be installed in a wooden boat, without the boat catching fire.

He tried a number of experiments with limited success, problems such as the paddle wheel disintegrating preventing a fully successful trial.

From 1800 Symington continued his work under the patronage of Thomas, Lord Dundas, who had an interest in the Forth and Clyde Canal.

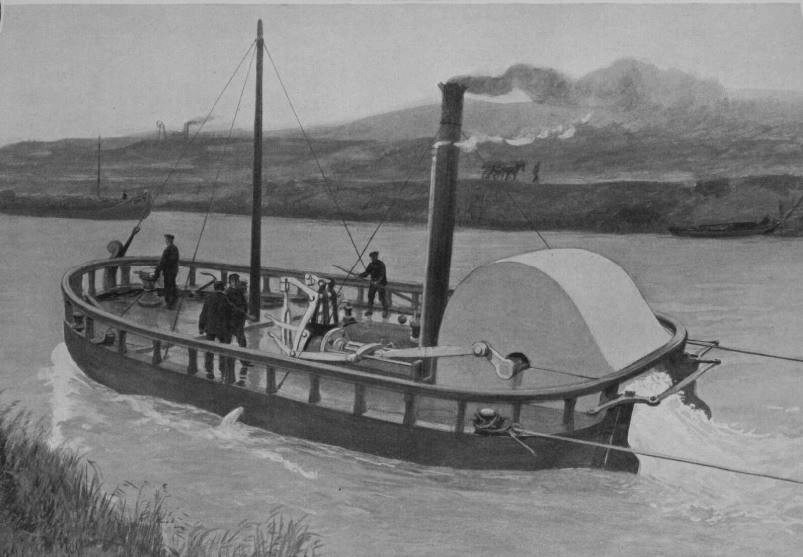

A first trial of a steam boat on the River Carron ended in failure. The second trial was with a new boat named the Charlotte Dundas after Lord Dundas’ daughter. This successful trial included the Charlotte Dundas towing two barges over a distance of 18.5 miles.

Although the trial was a success, there were concerns with the damage that the wash from a steamboat would do to the banks of a river or canal. Symington had also received an order from the Duke of Bridgewater for steam boats on the Bridgewater Canal, however this was cancelled when the Duke died.

As opportunities for Symington’s steamboats collapsed, he moved to the management of a colliery, however this ended in a legal case following which Symington was a rather poor man.

So far, all his time had been spent in Scotland. The London connection starts in 1829, when Symington, in poor health and in debt, moved with his wife to London to live with his daughter and her husband. He would die just two years later and be buried in the churchyard of St Botolph without Aldgate.

William Symingtons steamboat, the Charlotte Dundas:

His reputation was somewhat restored during the later half of the 19th century, and the monument in the church was installed in 1903.

Symington was possibly the subject of some skulduggery. Reading newspaper reports and letters after his death reveal stories such as the following from a Robert Bowie who wrote to the Shipping and Mercantile Gazette on the 5th May 1838:

To the editor of the Shipping and Mercantile Gazette:

Sir, Having observed the paragraph in your journal and in others to the effect that the American Government had granted £24,000 to the heirs of Robert Fulton, the ‘original founder’ of steam navigation. I beg leave to say that, whatever may have been Mr Fulton’s merit in introducing steam navigation to America, he had no right to the title of being its original founder, as he was but a copyist, and obtained, as will be seen by the following documents, the knowledge which enabled him to effect his purpose from William Symington, the first who propelled vessels by the power of steam.

Mr. Symington forms another instance for the page of history, of national ingratitude and neglect; and it is assuredly no great proof of the superiority of this country to America, that instead of rewarding him who conferred an inestimable benefit, his very petition for an investigation of his claims in parliament, was not allowed to be presented.

Fulton’s heirs have not been the only parties who have reaped the rewards of Mr. Symington’s labours. Even at home rewards were bestowed on Henry Bell, who barefacedly used Mr. Symington’s plans, and carried, it is recorded, the model of the first steam boat to Fulton in America. Henry Bell was frequently on board of Mr. Symington’s boats, and was often seen investigating the Charlotte Dundas after she was laid up near Glasgow; and it is a strange and rather suspicious circumstance that the model of a steam boat left by the late Lord Dundas and Mr. Symington in the Royal Institution, disappeared unaccountably from that building; and thus the ‘Fulton Steam Frigate’ as described in the first volume of Blackwood’s Magazine, was, with the exception of her warlike apparatus, a facsimile of Mr. Symington’s Boat.”

No idea if there is any truth in Mr Bowie’s allegations, but an interesting story of possible 19th century industrial espionage.

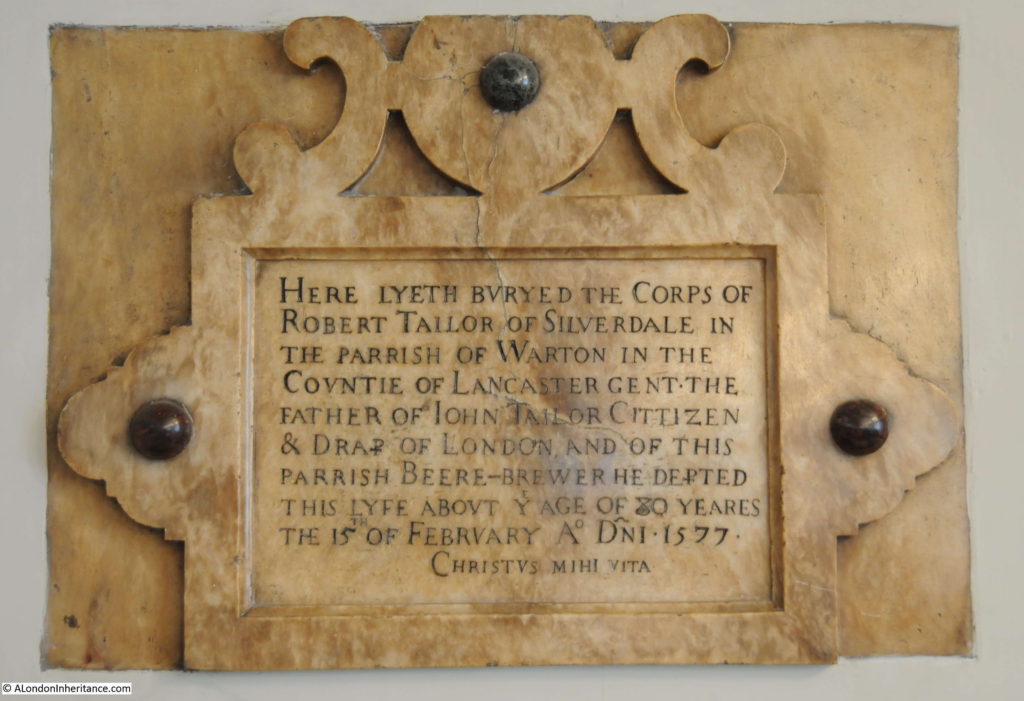

William Symington’s monument was installed in 1903. There are much older memorials in the church including the following from 1577 recording that “Here lyeth the corps of Robert Tailor”.

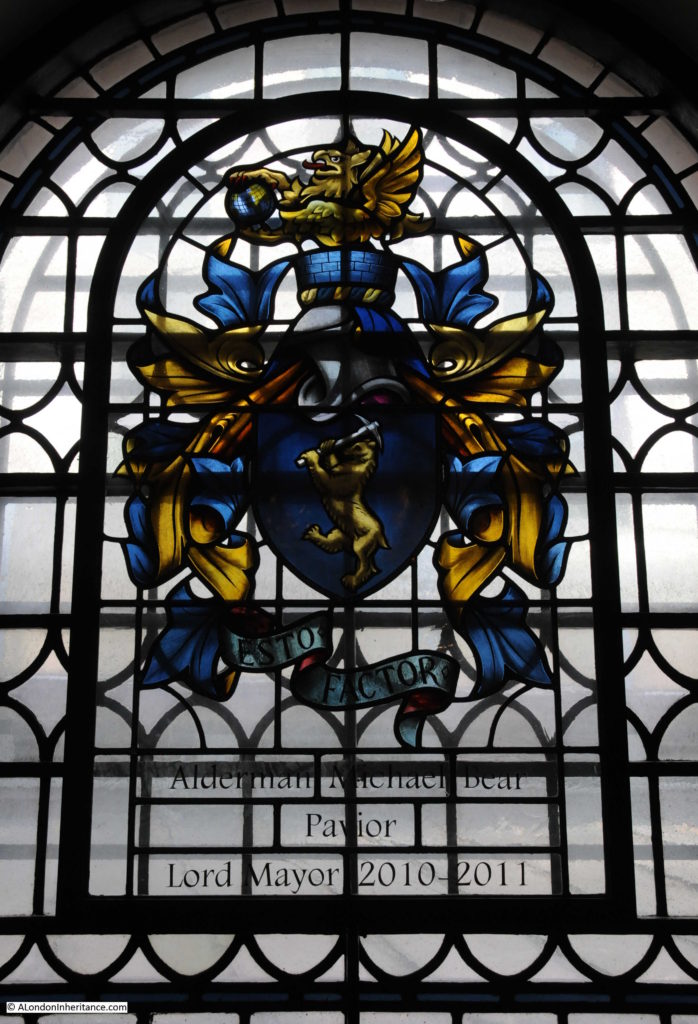

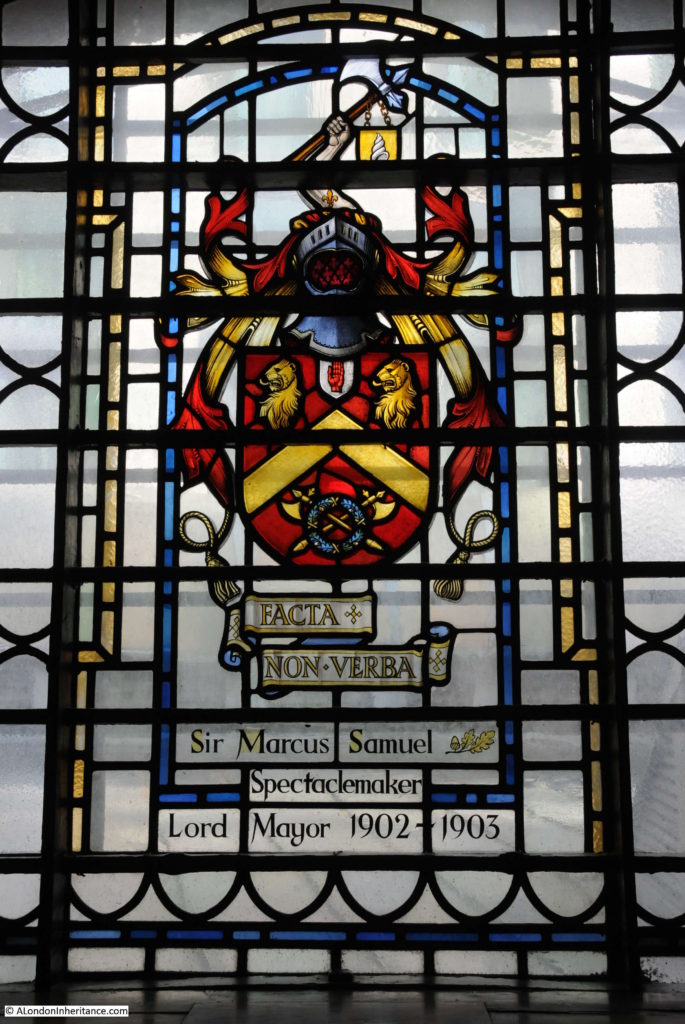

The windows of the church have stained glass recording Lord Mayors of the City of London and their Livery Companies:

The beautifully carved wooden panel in the following photo dates from the early 18th century (it was restored in 1971). The panel came from the church of St Mary Matfelon, Whitechapel when the church was destroyed by bombing on the 27th December 1940.

An 18th century sword rest:

St Botolph without Aldgate is a fascinating City church with a long history, which I have covered all too briefly in this post.

I was really pleased to find the location in Bevis Marks from where my father took his photo. The one remaining building in the area provided the key landmark to locate the viewpoint – amazing that this one building has survived the considerable redevelopment of the area over the last 60 years.

So intreguing…many thanks

Very interesting post, thank you

In your father’s original photo, the bomb site in the centre was the location of the Great Synagogue in Dukes Place. This was destroyed by enemy action during the war, as were virtually all the buildings to the north of St Botolphs up to Stoney Lane and Gravel Lane. I used to play on this bomb site when I lived nearby in the late 1940s early 1950s.

Mike, thanks for the feedback. I did wonder what was on the bomb site, but did not have time to research. The London bombsites as playgrounds are the same as my father’s recollections, an almost unlimited set of places for a child to explore and play.

Thank you for a very interesting few minutes which I look forward to

The pleasant open space alongside the church only opened relatively recently, following a major reorganisation of the road network at Aldgate. Previously there was a rather unpleasant road gyratory system occupying this space, with miles of pedestrian railings, walkers being forced to cross the roads by subways.

The open space is currently hosting an interesting outdoor exhibition of Victorian photographs of this part of the City.

this is a great interest for me Jerome Joseph Darcy, what a history lesson ,

Many thanks for this post: I used to live and work in this area which – even by London’s standards – is overflowing with historical details. In late Victorian times St Botolph was known as “the prostitutes’ church”: a number of Jack the Ripper’s victims’ corpses were discovered on its grounds.

I came to this via your post of 20 April 2023. I cannot leave a comment on that post, but I wanted to say that both posts are very interesting. Thank you!