One of the challenges with the blog is that there are many updates I would like to add to previous posts. If I update the original post, then the update will be part of a post that could be from several years ago, so not very visible, therefore for this week’s post, I thought I would cover three very different updates to past posts.

The last two are based on feedback from readers, which is always greatly appreciated. The first is following a recent decision by the City of London Corporation, regarding:

The future of Smithfield and Billingsgate Markets

The City of London Corporation has been looking at relocating the Smithfield and Billingsgate markets for some years.

Smithfield Market is set to become a new cultural and commercial centre, with the new Museum of London already under construction in the old General and Poultry market buildings.

Billingsgate Market moved out of Billingsgate in 1982, when the fish and seafood market moved to a new location by the North Dock, between the northern edge of the Isle of Dogs, and the A1261 Aspen Way.

Originally, the City of London Corporation were planning to relocate both markets to Dagenham Dock, a location that was not popular with the market traders, and in November 2024, the City of London Corporation abandoned this move, and appeared to take an approach where traders would be helped to move to other locations, without having a single location available.

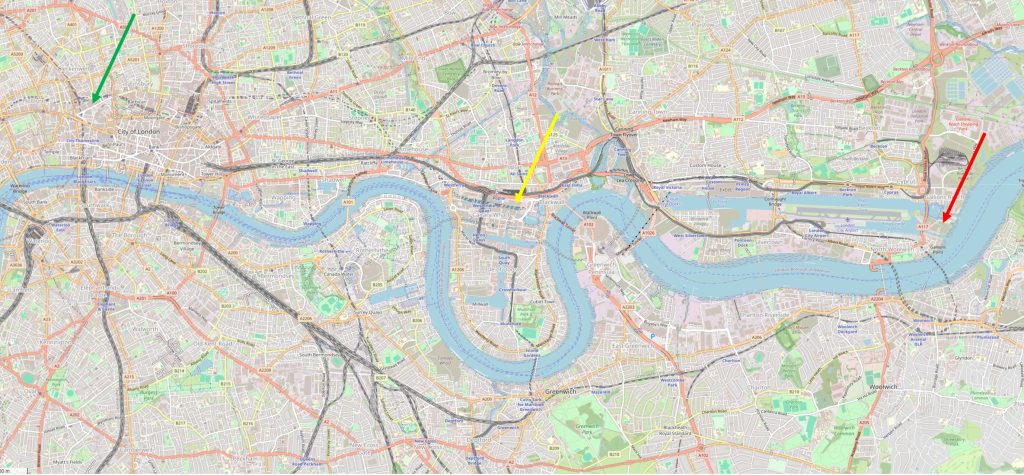

At the start of December 2025, the City of London Corporation announced a new policy, that the two markets would be consolidated and moved to a new location at Albert Island at the eastern end of the Royal Docks.

In the following map, the green arrow on the left shows the location of Smithfield market, the centre yellow arrow shows where Billingsgate Market is located today, and the red arrow on the right shows the future consolidated location of both markets, between the eastern end of the Royal Docks and the River Thames (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

In the following map, I have put a red line around Albert Island, the land which is planned to be used for the new markets (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

The land is currently derelict, with the majority of the buildings that once occupied the site having already been demolished.

At northern and southern ends, the land is bounded by two of the old locked entrances between the Royal Docks (a small part of which can be seen to the left), and the River Thames, on the right.

On the left centre of the map is the eastern end of the runway of London City Airport.

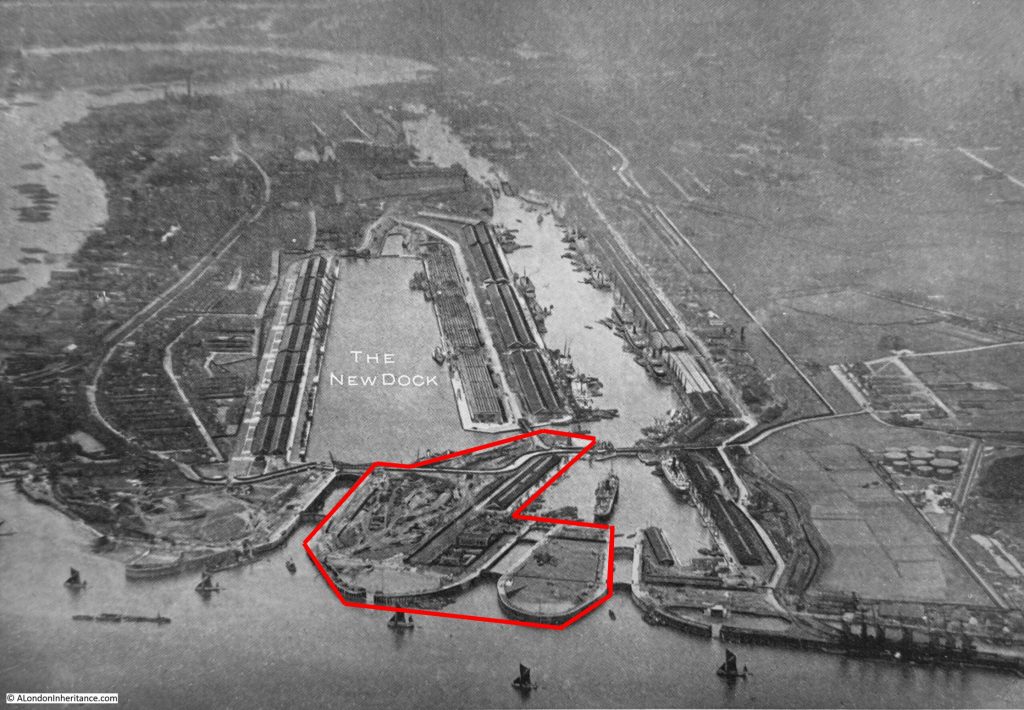

The following image is taken from the book that was issued to commemorate the opening of the King George V Dock in 1921. This new dock had not yet been officially opened by the King, so could only use his name once he had declared the dock open, which is why it is labelled as the New Dock in the image.

I have outlined in red the area of Albert Island as it was, following completion of the King George V Dock, the final dock of the three “Royals”:

As the plot of land is bounded on all sides by water, and the Royal Albert Dock is to the west, the plot of land goes by the name of Albert Island.

This location for the consolidated markets is a rather inspired choice.

It is a challenging location. Being at the end of the runway for London City Airport means that you could not build residential buildings. Even if these were built, they would have to be low rise, and would have the sound of planes either landing or taking off a short distance overhead.

The location is well connected from a transport perspective. In the above map, there is a road crossing towards the left of the plot. Follow this road north, and it connects to the A13, and south to the Woolwich Ferry, and further west to the new Silvertown tunnel.

The land has been derelict for some years, whilst the land around the rest of the Royal Docks has been gradually redeveloped.

Relocating the market here, will also bring a different activity to this part of east London, and will break up the rows of residential towers which have and continue to be built here, particularly along the land to the south, between the Royal Docks and the Thames.

I explored the area back in 2024 in a number of posts on the Royal Docks and surrounding areas. If you have been on my walk “In the Steps of a Woolwich Docker – From the Woolwich Ferry to the Royals”, you will also recognise Albert Island.

Firstly, this is why the site would not be suitable for residential. This photo was taken from the road that runs over Albert Island and shows that the land is at the eastern end of the London City Airport runway:

Starting from the north, this is a walk along the road over Albert Island showing how the area looks today. In the following photo, the end of residential development to the north can be seen, as well as the old locked entrances between the dock and the river. The start of Albert Island is the undeveloped land to the right of the residential:

The original eastern entrances between the Thames and the Royal Albert Dock:

Heading south and this is the central part of Albert Island. The majority of buildings associated with the docks were demolished some years ago, leaving the outline of walls, paths, streets and the concrete floors of long lost warehouses and industrial buildings:

There are still a few old streets that thread across the site, generally bounded by large growths of vegetation:

The main entrance from the road that crosses the site to Albert Island:

At the southern end of Albert Island is the locked entrance between the Thames and the King George V dock. This photo is looking at the northern side of the lock channel, which will become part of the new market site:

Also back in 2024, I had a walk around Albert Island. This is one of the old streets that thread the site, along with the one remaining warehouse building on the left:

Some of the few roads across the site were fenced off:

The only route across the island back in 2024 was a footpath that ran alongside the Thames, at the eastern edge of Albert Island. This is the footpath heading towards the Thames:

At the corner:

In the following photo, on the left is the Thames, on the right is Albert Island. It was a hot day when I went for this walk, and my main memory of this stretch is the hundreds of butterflies that were in the bushes on the right. As you walked along the footpath, they would rise out of the bushes, before settling back after I had passed – it was a rather magical place, also with the Thames on the left:

At the end of the footpath, steps up to a short path that went up to the locked entrance to the King George V dock:

Crossing the lock, and looking back towards the King George V dock. This channel marks the southern boundary of Albert Island, and the new market area which will be on the right:

The above photos were taken back in 2024, last year, 2025, I went on another walk through the area whilst I was planning my Woolwich to Royal Docks walk. I had intended to walk through Albert Island, however this proved impossible, as the crossing over the locked entrance between the Thames and King George V dock was then closed, and there was no clear route through.

I did try some options, but every route ended in fencing, or some other obstruction.

In the following photo, I had just walked along the footpath shown to the left of the photo, and optimistically found this sign for a footpath:

I followed this apparent footpath, and it ended in a waterlogged channel with no way through:

The relocation of the two markets is subject to the passing of a Parliamentary Bill to allow the old markets to be closed at their current sites, along with planning permission from Newham Borough Council for the Albert Island site, and I suspect neither of these will be a problem.

The 3rd of December press release stated that the markets “will continue at Smithfield and Billingsgate until at least 2028”, and I suspect that clearing the current site, any remedial work that needs to be done on what was an industrial location, followed by the new build, will take more than a couple of years, so the “at least 2028” suggests the possible timescale.

When the two markets have moved to Albert Island, they will be called “New Billingsgate and New Smithfield”, although for Billingsgate this is the second move after the original 1982 move from the original Billingsgate in the City.

Regarding the existing market locations, an updated press release on the 2nd of January 2026 states that “at Smithfield, the Grade II* listed buildings will become an exciting international cultural and commercial destination to complement the London Museum, which is moving next door”, and that “Plans for Billingsgate will deliver up to 4,000 much-needed homes in an inner-London Borough, alongside a new bridge across Aspen Way to help address the social, economic and environmental disparities between Poplar and Canary Wharf.”

It is a shame that Smithfield is moving from its City location as it was the last City market in its original location, and ends an activity that has taken place in the City for hundreds of years.

Having said that, the new location is good. It makes use of an otherwise difficult to use plot of land, it brings diversity of function and employment to the area around the Royal Docks, and in many ways it continues the tradition of the Royal Docks, as a place where products were stored, traded and moved on to their eventual location.

Albert Island has a website, which does not yet mention the move of the Smithfield and Billingsgate markets, and still covers the original proposals for a commercial shipyard, marina, university hub, and with easy public access to the Thames river path. Hopefully some of these will be part of the overall development. Bringing a shipyard back to the docks would be good, and access to the Thames river path would be essential. The Albert Island website can be found here.

The City of London Corporation announcement on the move of the markets to Albert Island is here.

It will be an interesting development to follow.

Horn Stairs

Horn Stairs are one of my favourite Thames stairs, as they lead down to a lovely part of the Thames foreshore. At low tide, a wide expanse of gently slopping foreshore, with superb view across to Limehouse and the northern part of the Isle of Dogs.

My last visit to Horn Stairs was in mid January 2024, and almost two years later, I walked to the stairs again following an update on the state of the stairs sent in by a reader.

The reader commented that the stairs had been closed as they had lost a couple of their top steps, had come away from the wall, and moved back and forth significantly with the tide.

They were in a poor condition when I visited two years ago, with rotting wooden steps, and their fixing to the wall not looking very robust, so I am surprised they have lasted for almost another two years.

When I went in January 2024, it was a bright, sunny day. My return visit in January 2026 was wet, overcast and raining.

On arriving at Horn Stairs, there was a footpath closed sign, and temporary fencing at the top of the access steps, which looked like it had been moved, or blown aside:

Very temporary fencing off of the stairs:

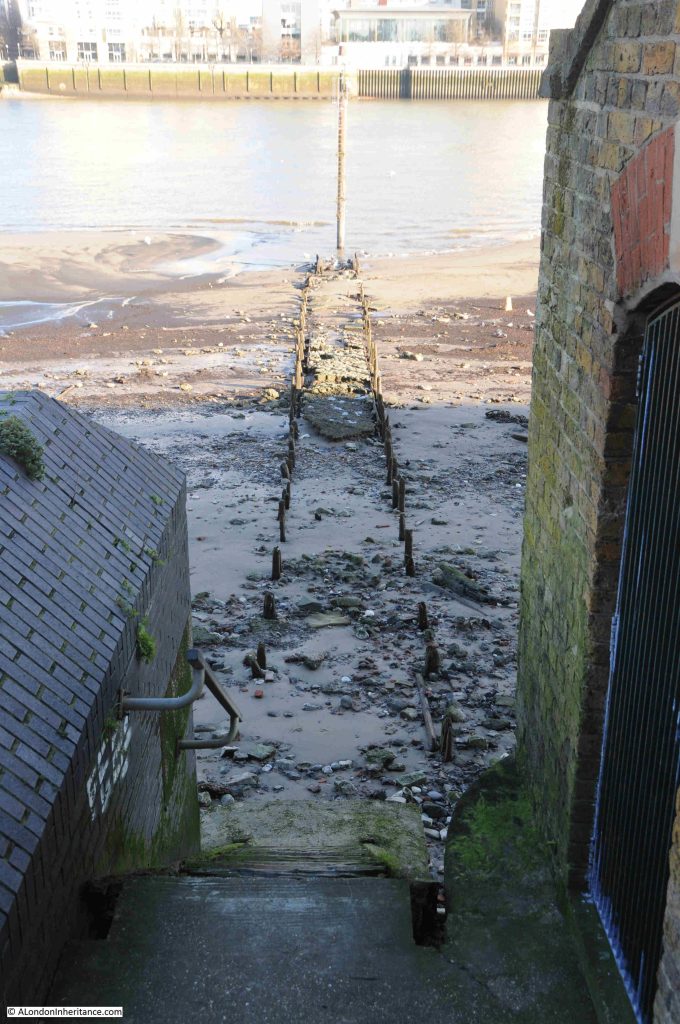

I walked through a gap and looked at the stairs and the remains of the causeway leading across the foreshore:

It was clear to see that the top steps are missing, the top section of steps do not look in great condition, and the fixings at the side have come away:

This was the stairs back in 2024, looking very dodgy, but not fenced off and it was possible to walk down:

Horn Stairs, and the area of foreshore to which they lead, has a fascinating history, which I explored in the post “Horn Stairs, Cuckold’s Point and Horn Fair”.

Some photos from my previous visit, when the weather was much better than January 2026. Firstly looking along the causeway across the foreshore:

At the end of the causeway is a navigation marker, shown on the PLA chart for this section of the river, with a wonderful view across to the towers that occupy the Isle of Dogs:

Looking back along the causeway, showing that during a low tide, there is a large expanse of dry foreshore:

Wooden stairs do not last as long as concrete or stone stairs, and there are a number of examples along the river where wooden stairs have not been replaced after they gradually fell apart (see this post on King Henry’s Stairs for an example). I am also not sure why some are concrete / stone whilst other are of wood. Whether the frequency of use, their importance or location along the river deemed some to be of a more permanent structure, or whether it just came to costs at the time.

I have emailed both the Port of London Authority and Southwark Council to see if there is any information on who would be responsible, are there any plans to replace the stairs etc.

It would be a great shame if the stairs at Horn Stairs were not replaced.

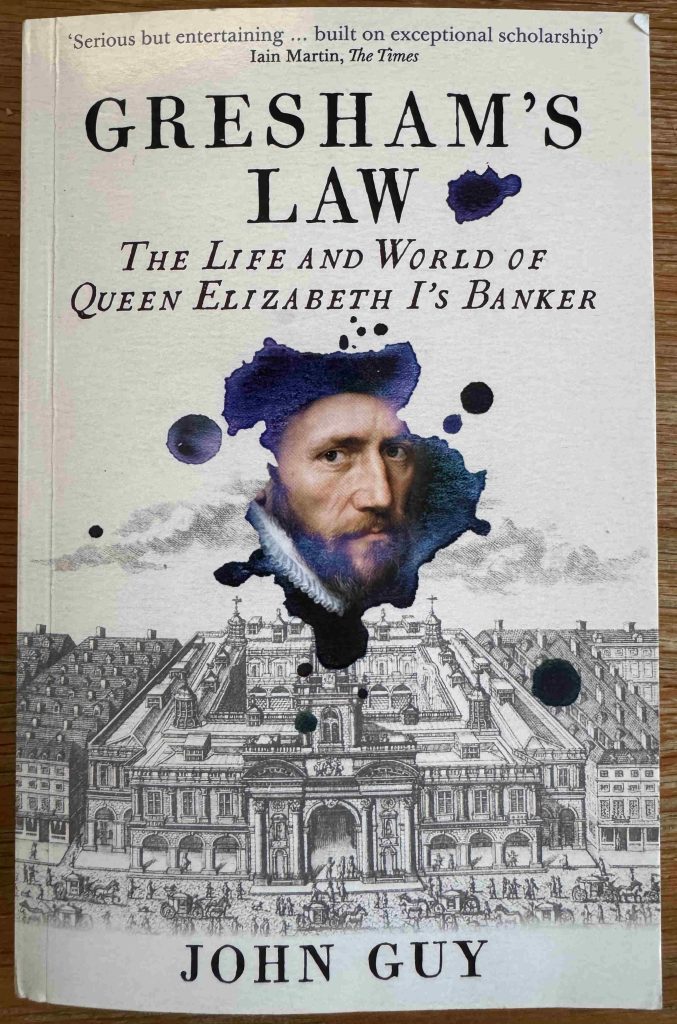

Sir John or Sir Thomas Gresham – The Trouble with Identifications

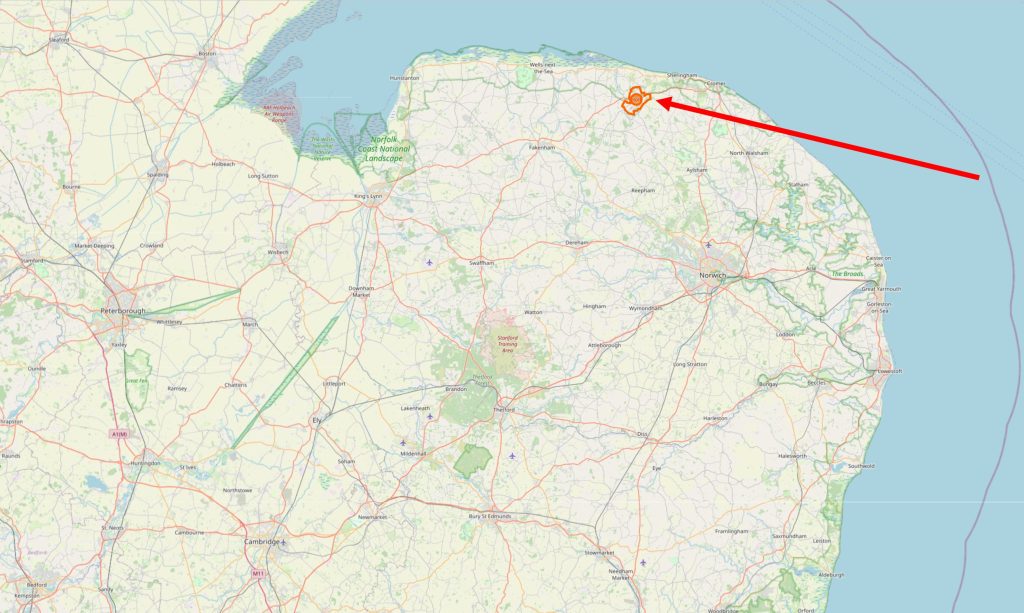

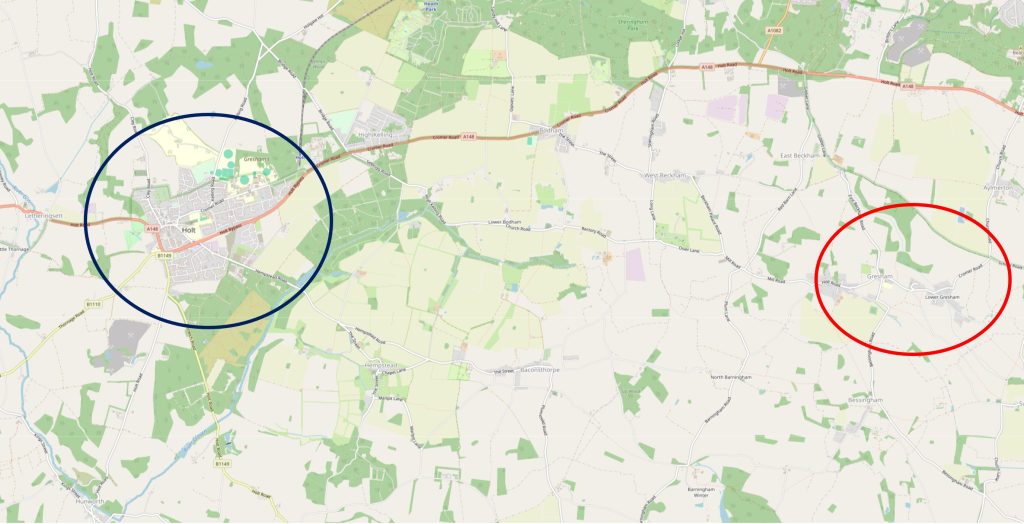

A couple of week’s ago, I wrote a post about the Greshams of Norfolk and London.

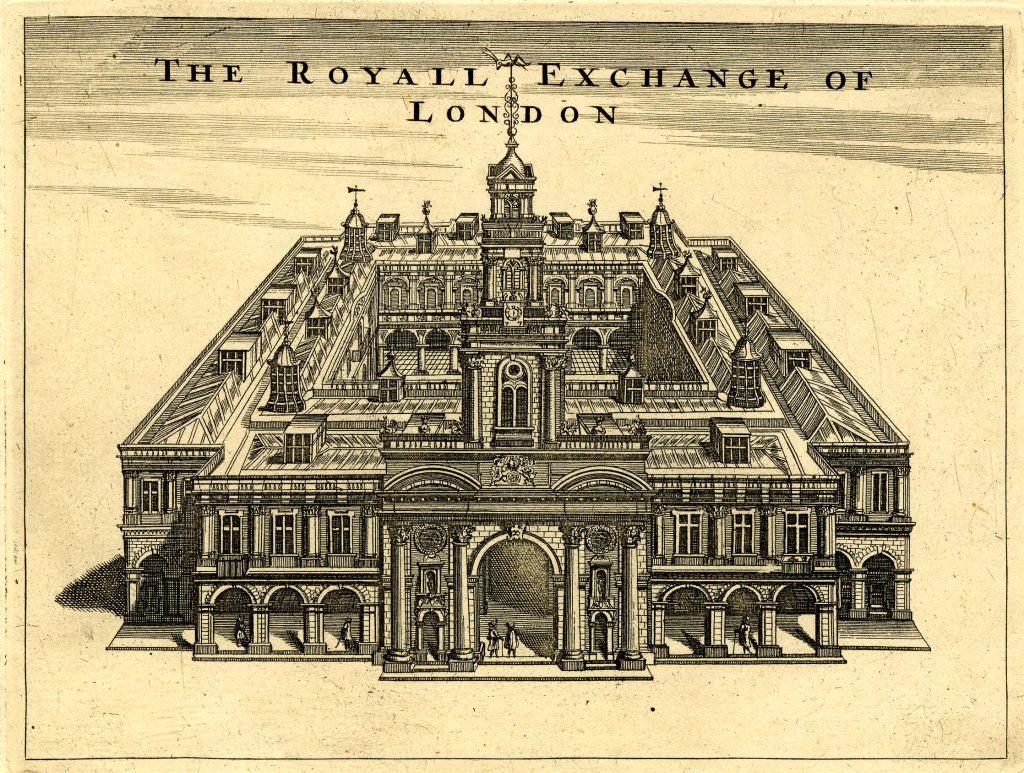

The post told the story of Sir John Gresham, the founder of a school in the town of Holt in Norfolk, a member of the Mercer’s Company and a Lord Mayor of the City of London, along with his nephew Sir Thomas Gresham who was also a Mercer and through his Will, in 1597, Gresham College was established, to be run and administered by the City of London Corporation and the Mercer’s Company.

I included images of both Sir John and Sir Thomas Gresham in the post.

One reader commented “A very interesting post. The picture of ‘Sir John Gresham’ and the engraving of ‘Sir Thomas Gresham’ are identical: the engraving is laterally reversed because of the engraving technique, but otherwise the images are the same, even down to the number of done-up buttons and the hand holding the gloves. It’s the same man! Either the attribution of the painting is wrong or that of the engraving – probably the latter, I think.”

So I went back to the images and yes, they do look as if they are of the same person.

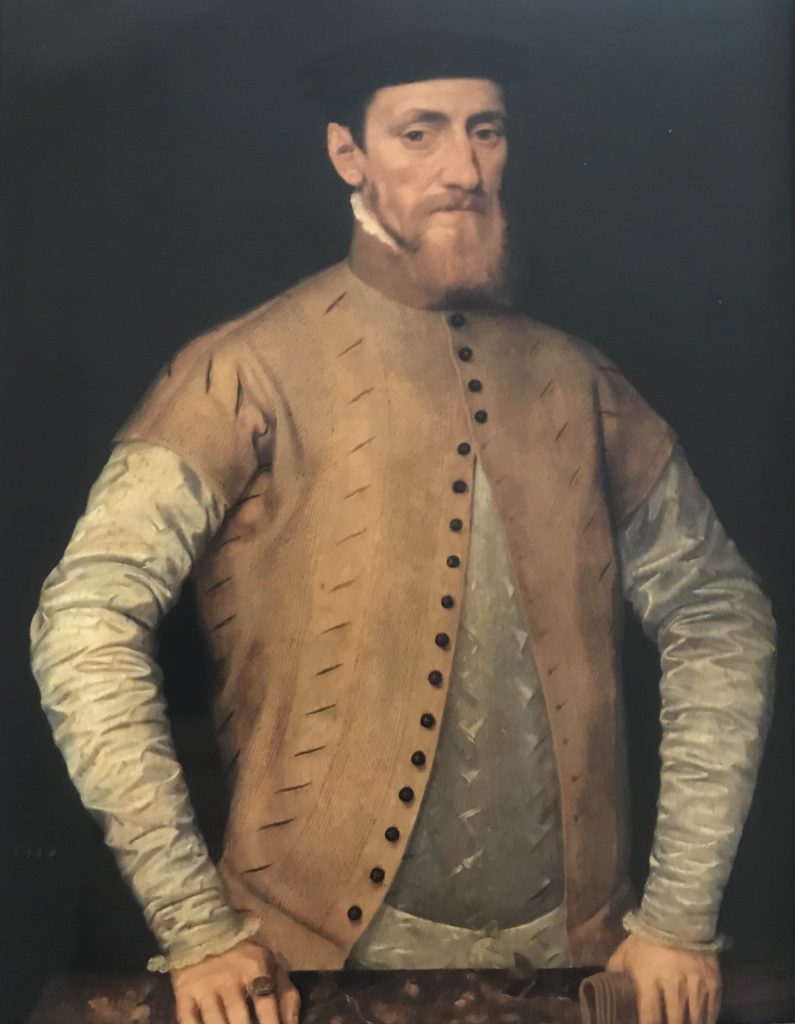

This is the image of Sir John Gresham:

I found the above image on Wikimedia, with the description “Portrait of Sir John Gresham (1495–1556)”.

As a general rule, I never take anything on Wikipedia / Wikimedia (or the Internet in general) as absolute fact, without finding supporting evidence, and in the search for evidence to support the Wikimedia description, I found the same image in the National Trust Collections website, where it is attributed as “Portrait of a Man, possibly Sir John Gresham the elder” I also found the same image at the Alamy website, (a stock image service company, where images are made available for a price, for use in other forms of media) where the image is described as “Sir John Gresham (1495 – 1556) English merchant, courtier and financier”.

So the image I found on Wikimedia was also described by the National Trust and Alamy as Sir John Gresham (in fairness to the National Trust they also included “possibly”), so I was happy to use the image from Wikimedia.

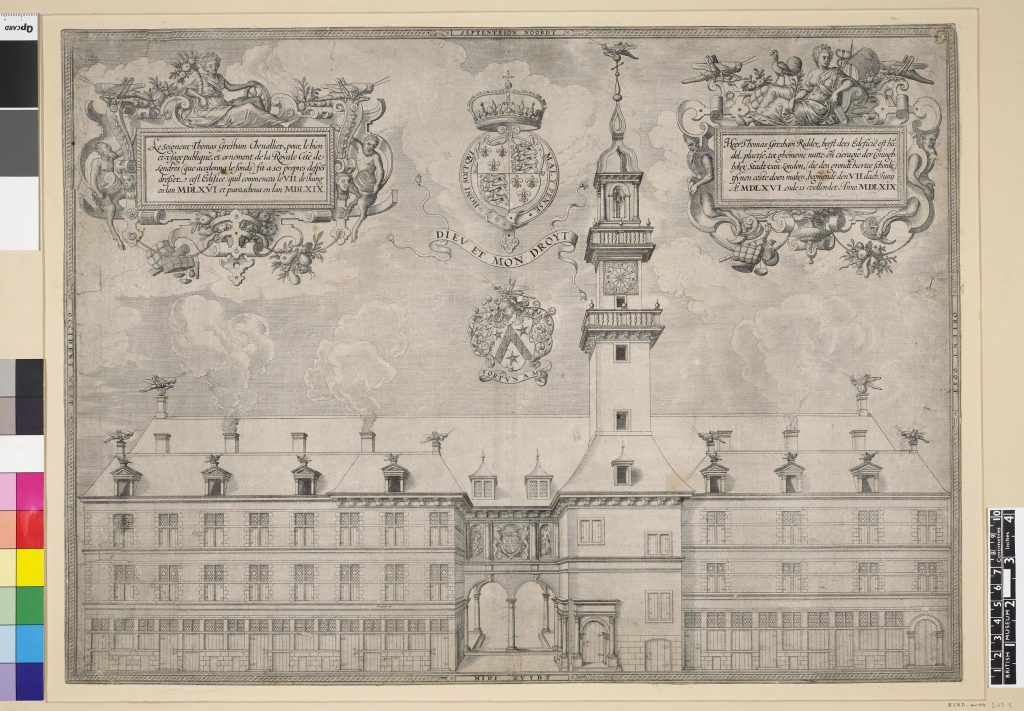

The following image of his nephew, Sir Thomas Gresham, is from the British Museum collection, and was an engraving by John Boydell of Cheapside, London and published on the 1st of May, 1779, and is described as being taken from “In the Common Parlour at Houghton”, which is presumably Houghton Hall in Norfolk, a county where the Gresham’s had property, hence the link with the town of Holt in my post:

To provide a good comparison between the two images, I converted the image of Sir John Gresham to black and white, and reversed the image (the reader commented that the image could have been originally reversed due to the engraving technique, therefore reversing again would get the image back to the original).

Now putting the two images side by side, we get the following (Thomas Gresham on the left and John Gresham on the right):

They look almost identical, down to the creases on the clothing, the number of buttons, the pose, the clothes, etc.

There are minor differences, however I suspect that these are down to the engraving (on the left) being made from the portrait (on the right).

I assume the process to create prints such as these, which were in wide circulation in London in the 18th century, was that an artist would visit Houghton Hall and make a copy of the original painting. As this was a copy, there would be minor differences to the original painting.

This copy was then used to create the engraving which John Boydell then published from his premises in Cheapside.

So is the image of Sir John or Sir Thomas Gresham?

I suspect it is of Sir Thomas Gresham, as the following image is from the National Portrait Gallery collection, and has the following reference: “Sir Thomas Gresham by Unknown Netherlandish artist

oil on panel, circa 1565″:

Attribution: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported. Source National Portrait Gallery, London

Although the clothes are very different, the likeness, facial expression, the beard all look very similar to the painting and print.

This would mean that the National Trust is incorrect to state that their painting is Sir John Gresham, although again, they do state “possibly”.

To add a bit more confusion, in the print of Sir Thomas Gresham from the British Museum, the “size of the picture” is stated as 2ft, 1inch by 2ft 9 3/4 inches. whilst the National Trust give the dimensions of the painting of Sir John Gresham as 36 x 26 in, and that the painting is located at Dunham Massey in Cheshire.

So the painting is larger than that given in the print, and today is in a different location.

This confusion of Gresham’s shows just how hard it is to be certain of the facts when identifying anything painted, engraved or printed from some centuries ago. If I had the time, I would want to track down more original artwork of both the Greshams and see if this could come to a consensus of appearance of these two, whose contributions to the City of London can still be seen today.

I always try and make sure that the images used, and the detail in my posts is as accurate as possible. I use visits to the sites I am writing about, books and maps (of an age as close to the time I am writing about the better), newspapers from the period, and where I use the Internet, it is from reputable sources such as the British Museum Collection, and anything else is cross checked with other sources.

As the Gresham images show, it is hard enough to be sure of the facts of what we see, whether an image is of who we are told it is, but AI, which always seems to be in the news these days, is going to make this much, much worse.

I will never use any AI generated content in my posts, whether text or image, and to demonstrate why, I asked ChatGPT to generate an image of Sir Thomas Gresham, and this was the result (ChatGPT made the decision to produce a portrait “in velvet” for some reason):

The above image shows the dangers of where we are heading with AI image creation. Without any context, this could easily be taken as a painting of Sir Thomas Gresham. It took less than a minute to create, and is why we are moving into a dangerous period where we have no idea whether what we see or read is real or not.

And for all the comments that my posts receive, two of which were used for today’s post, thank you. I learn much, and they add considerably extra context and information to the post, which is what it should be, rather than machine generated content.