A rather somber post this week, following a return to a location I was last at forty years ago. In the late 1970s, after leaving school, I started an apprenticeship with British Telecom (or Post Office Telecommunications as it was then). It was a brilliant three year scheme which involved both college and practical experience moving through many of BT’s divisions and locations. For a couple of months I was based at the telephone exchange at Brentwood, Essex. A typical day would involve maintenance and fault fixing on the telephone exchange equipment, however at the start of a day that would be rather different, the Technical Officer in charge was giving out jobs, and one job involved fixing a fault at a rather unique location – a secret nuclear bunker.

I had just left school, so at the time this was a genuinely exciting experience as I headed out in one of BT’s yellow vans with a couple of other engineers.

I have always wanted to revisit the site and was in the area recently so I took the opportunity to return to what is now a tourist attraction as the Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker.

The decades prior to the collapse of the Iron Curtain and the Soviet Union, and the very real threat of nuclear war now seem many years ago, however with recent international politics a visit to the secret nuclear bunker is a thought provoking and very real reminder of what the impact of such a war would be, and the futility of preparing for such an event.

The origins of the bunker are in the early 1950s when the Government realised there was an urgent need for an improved air defence system to provide an early warning system to detect incoming enemy aircraft. The scheme, code named Rotor consisted of a number of radar systems and bunkers built across the country. Small R1/2 bunkers were built at radar sites whilst a small number of much larger R4 bunkers were built, the bunker at Kelvedon Hatch being one.

The bunker was operational by 1953 and being used for coordinating air defence.

In the 1960s the role of the bunker changed from being an air defence operations centre, to an emergency regional seat of government for London. The assumption being that in the build up to a nuclear war, key members of government would leave London and head for the bunker, along with scientists and civil servants. Those safe in the bunker would monitor and attempt to coordinate what was happening on the surface, then weeks after the nuclear confrontation, would emerge from out of the ground and attempt to establish some form of government across what ever remained on the surface.

This was the role of the bunker during my visit to look at a fault on the telephone exchange deep underground.

By definition, a secret nuclear bunker is secret, so there is very little visible on the surface. The entrance to the bunker is through what was meant to look like a typical rural bungalow or farm building sitting on the side of the hill. This is the view on my recent visit – very similar to my first visit when we pulled up outside in the BT van.

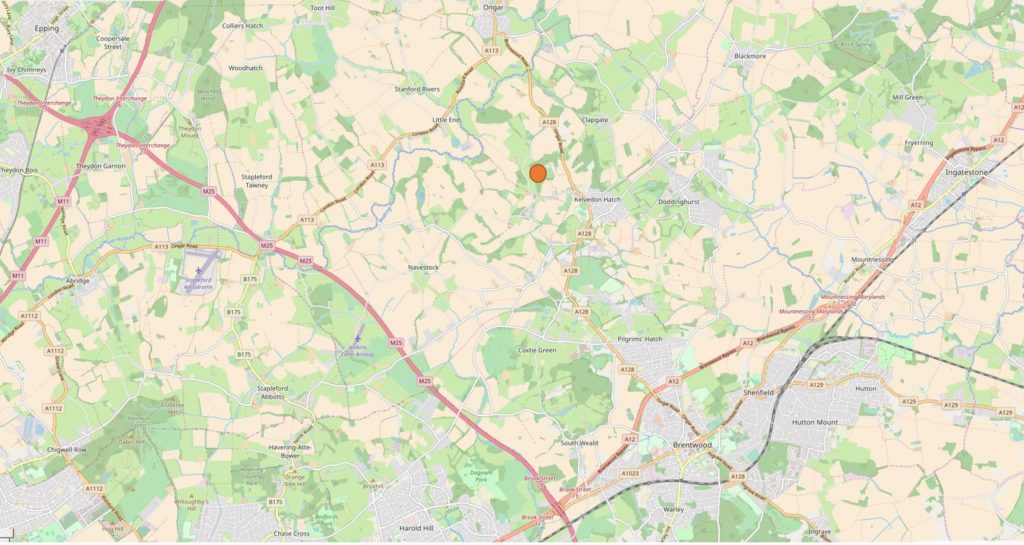

To give an idea of the rural location of the bunker, it is marked with an orange circle in the following map. The M25 runs from lower centre to top left and the town in the lower right is Brentwood (Map “© OpenStreetMap contributors”).

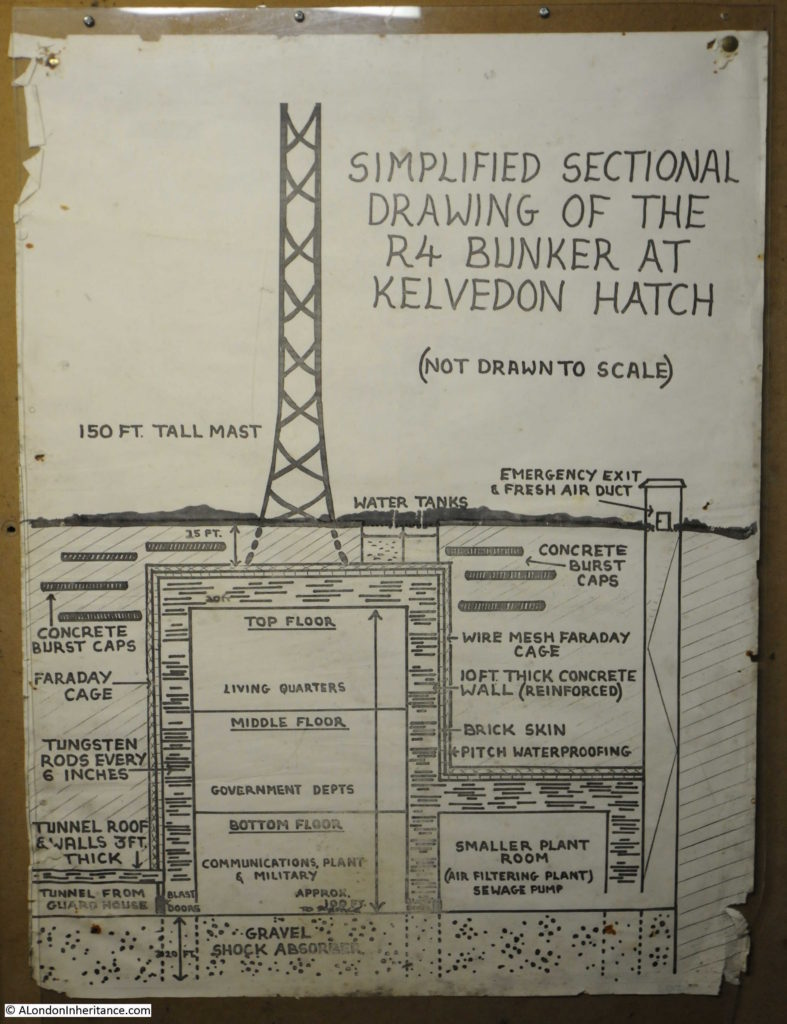

The bunker was constructed by excavating a very large hole, laying a gravel base to act as a shock absorber then building the bunker with 10 foot thick concrete reinforced walls designed to withstand the blast from a nuclear weapon, with the walls surrounded by a wire mesh acting as a Faraday Cage to absorb the effects of an electromagnetic pulse which would have damaged the electronic devices within the bunker.

The excavated materials were then used to cover up the bunker and create a hill on top to provide further protection. The bunker was equipped with its own means of generating power, purifying air, maintaining temperature and had suppliers of water, and in the lead up to a war, would have been stocked with food to keep the inhabitants sustained during their weeks underground.

A plan of the bunker is shown in the following photo:

When operational, the bungalow acted as a guard house and it was through here that we entered to be checked and signed in ready to visit the telephone exchange. Today, there are no armed guard at the entrance. All you have to do is pick up the audio tour device.

The bunker is then entered through a long entrance tunnel that leads from the bungalow down to the base of the bunker. The view looking down:

The view looking back up:

At the end of the entrance tunnel are blast doors leading into the bunker. The entrance to the body of the bunker is also an L shape to deflect any blast that breached the doors.

Looking up at the three levels of the bunker:

The Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker was decommissioned in the early 1990s. It was removed from the secret list, and the Government removed the majority of the equipment within the bunker. It was then sold back to the farming family from whom the land had originally been purchased, and they reequipped the bunker and opened for visitors.

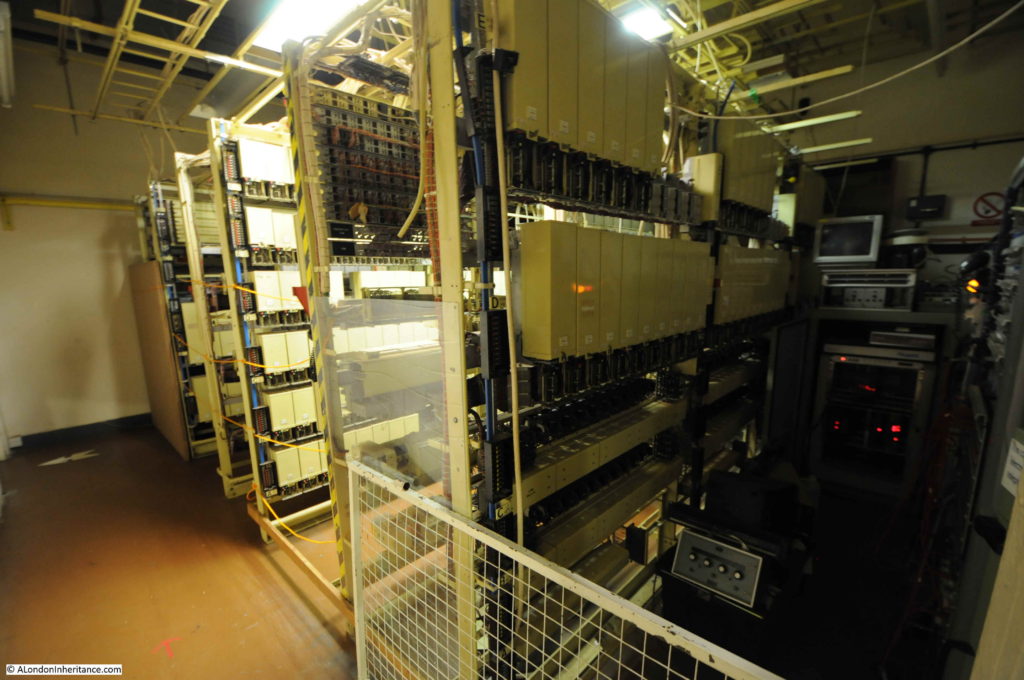

This is the room I had come to see. The telephone exchange for the bunker that would connect the internal telephones with the outside world (on the assumption that there would still have been someone in the outside world able to answer a phone and that the infrastructure had not been destroyed).

The telephone exchange equipment is not original. It was a Strowger electro-mechanical exchange, before being replaced with an electronic exchange. A Strowger electro-mechanical exchange has been reinstalled – the same type of equipment that was in the bunker when I was there as an apprentice. If my memory of 40 years is right, it does look much the same as when I was there in the late 1970s.

I recall a few people around and some calls going through the exchange, but it was very quiet compared to what it would have been during a real event when up to 600 people would have been working in the bunker. The exchange room was the only one we went to – it was not the sort of place you could have wandered round for a look. When we had completed our work, it was back up the tunnel and out into daylight.

Many of the other rooms have been equipped to show what they would have looked like at the time. Here, teleprinters ready for sending and receiving printed information with the outside world.

The secret nuclear bunker was equipped with a BBC studio. From here, broadcasts would have been made to the general population above ground.

A few years ago, the BBC released the transcript of the announcement that would have been broadcast in the event of a nuclear war. The transcript starts:

“This is the Wartime Broadcasting Service. This country has been attacked with nuclear weapons. Communications have been severely disrupted, and the number of casualties and the extent of the damage are not yet known. We shall bring you further information as soon as possible. Meanwhile, stay tuned to this wavelength, stay calm and stay in your own homes.

Remember there is nothing to be gained by trying to get away. By leaving your homes you could be exposing yourselves to greater danger.

If you leave, you may find yourself without food, without water, without accommodation and

without protection. Radioactive fall-out, which follows a nuclear explosion, is many

times more dangerous if you are directly exposed to it in the open. Roofs and

walls offer substantial protection. The safest place is indoors.”

The full transcript is a rather sobering read and can be found as a PDF on the BBC’s website here.

In the late 1970s there was also considerable discussion in Government about how much preparation there should be, and how much the public should be informed about preparing for an attack. Tensions were heightened in 1979 with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

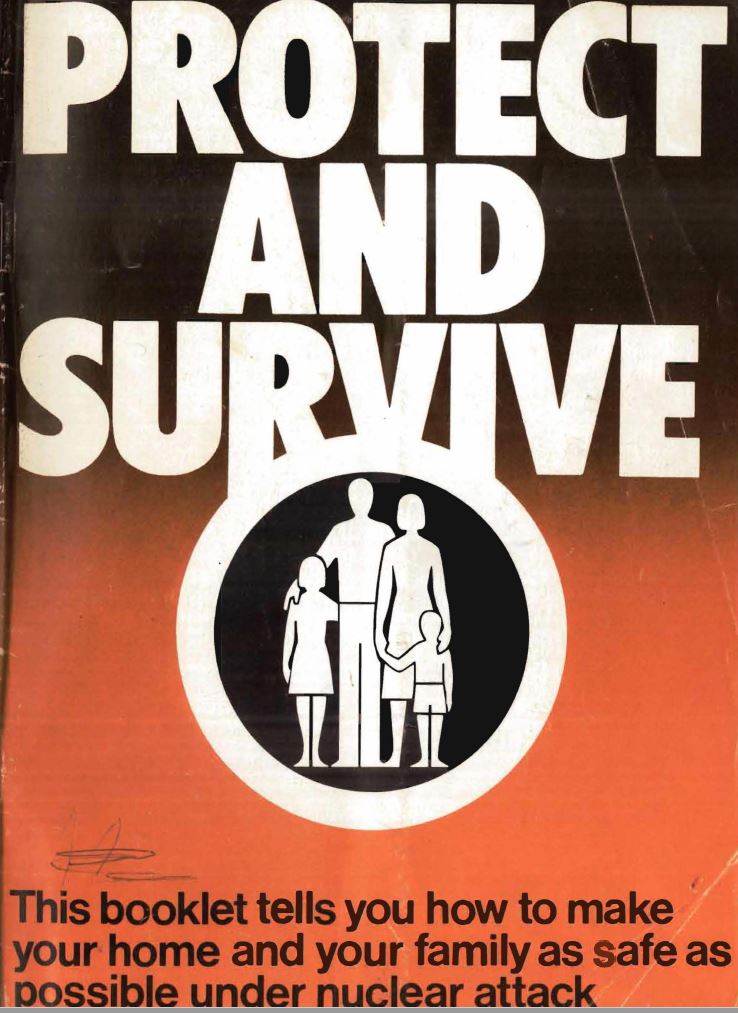

As part of the planning to prepare the general population for an attack, the Protect and Survive booklet was written. This would have been distributed to all households across the country in a period of heightened tensions when a nuclear attack was seen as a possible outcome.

The booklet included advice on how to prepare for an attack and how to survive in the days after an attack.

The front cover of the booklet:

The front cover is from the Woodrow Wilson International Centre for Scholars and the full booklet is available as a PDF download at the URL in the following citation for the source:

Document-110193, Author = Great Britain. Central Office of Information and Great Britain. Home Office, Title = Protect and Survive, URL = http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/110193

Institution = Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars publisher = History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive

A film version of the booklet was also produced for broadcast on TV during the possible lead up to an attack. There is a copy on YouTube here.

The early 1980s also produced some landmark TV and films covering the impact of nuclear war. In September 1984, the BBC produced film Threads was shown on BBC2. A genuinely frightening portrayal of the impact of nuclear war on the city of Sheffield. A sample of the film can be found on YouTube here. I remember it as one of the most frightening programmes I have ever watched then or since on television.

Another example was the 1986 animated film of Raymond Briggs graphic novel, When the Wind Blows.

My just out of school, apprentice excitement at going to such a place as the secret nuclear bunker was most certainly taken back down to earth with the reality of what such a war would mean as depicted in the films mentioned above, as well as so many other books, films, and programmes of the time.

Continuing around the bunker, there is a re-creation of what the room may have looked like where plots would have been drawn on large maps showing where bomb blasts had taken place.

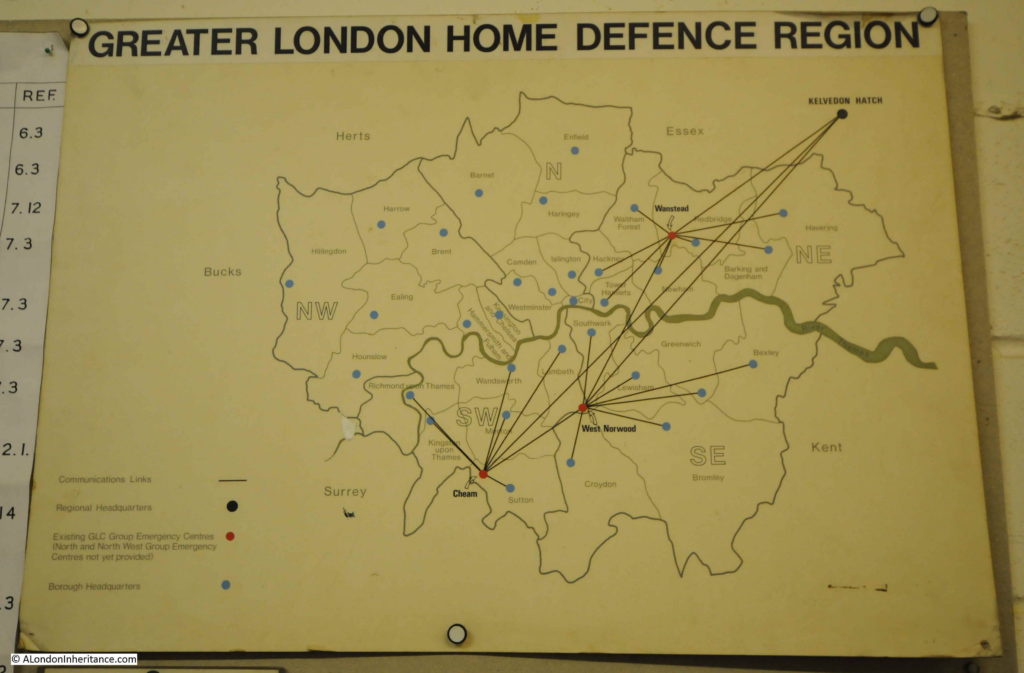

The position of the Kelvedon Hatch secret nuclear bunker as the regional headquarters for the Greater London area is shown in the following photo:

Continuing further down in the bunker and the air filtration plant. This would have taken in air from the outside and filtered to remove dust and radioactive particles.

The machine room where equipment maintained the air conditioning of the bunker.

There are a couple of rooms within the bunker where senior Government officials would have had their own room. One of which was available for the Prime Minister should they have been able to get out of London and into Essex in time.

The main operations room where representatives of Government departments, the armed forces, transport, energy etc. would have been represented.

Apparently some of the few items not removed by the Government when they vacated the bunker are the signs around the operations room indicating the working space for each of the Government departments.

The bunker also contained facilities to accommodate the staff who would have been based here during an attack.

Up to 600 people would have been based in the bunker in the event of a nuclear war. Whether they would have had any contact with the outside world during their time underground is questionable, and one can only imagine the scene that would have met them when they emerged onto the surface after weeks in the bunker.

It was interesting to return after 40 years. The world is now a very different place, but having places such as the Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker available to visit are essential to provide a reminder of the real horrors of nuclear war.

Full details are on the web site of the bunker. Thanks to the owners of the bunker for letting me use my photos of the interior.