All my walks have sold out, however I have had a request to run the “South Bank – Marsh, Industry, Culture and the Festival of Britain” walk on a weekday, so have added a walk on Thursday, the 9th of November, which can be booked here.

I have now been writing the blog for nine and a half years, and it has changed the way I look at things when walking the streets of the city. I now take far more notice of all the little indicators to the history of an area, a street or a building.

Whether it is the way that streets dip and rise, and the sound of running water rising from below a drain cover, both hinting at a lost river, the way the shape of a building hints at an early street pattern before a Victorian road improvement, or the numerous plaques and architectural features telling of a building’s former use.

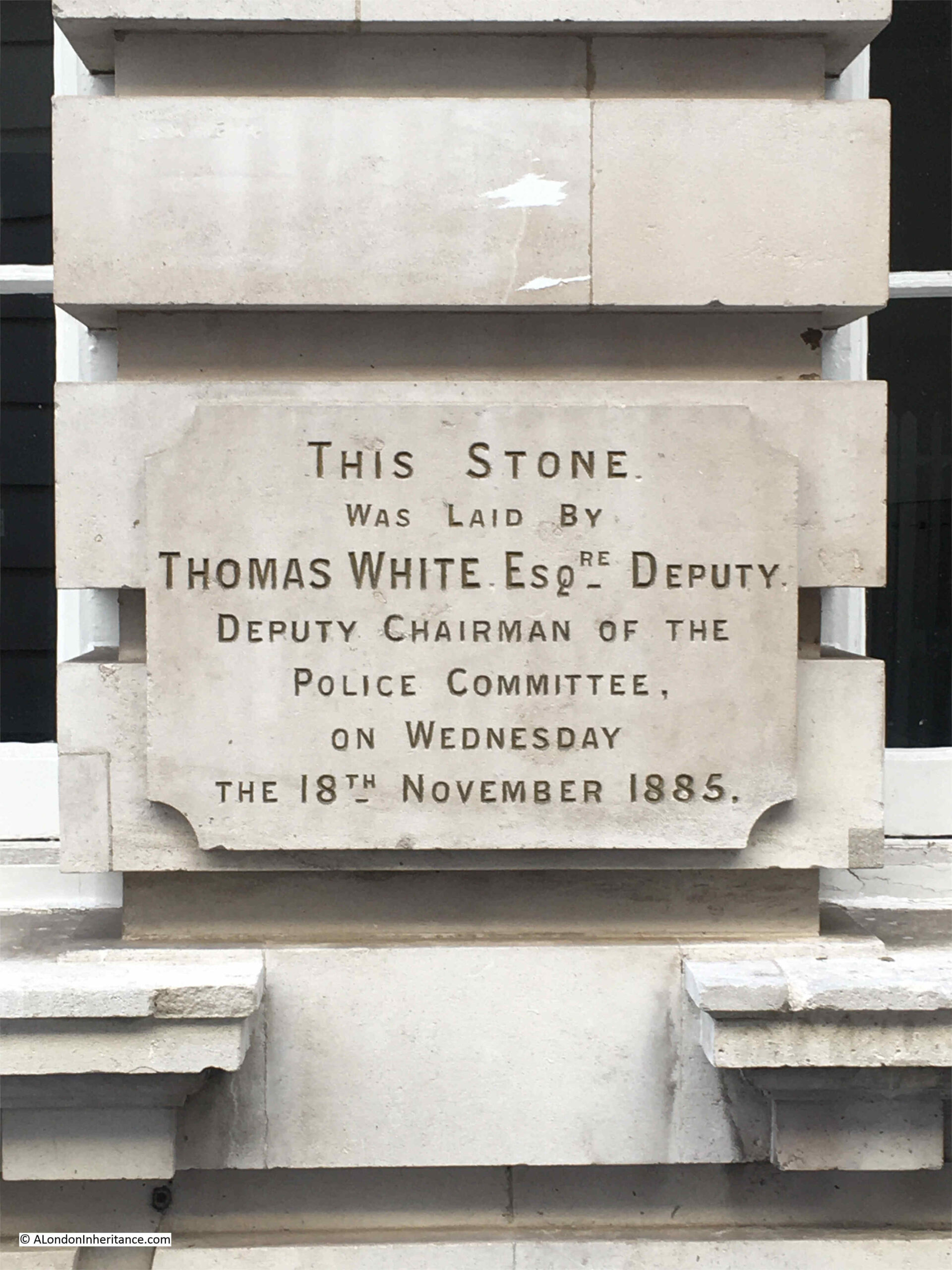

A typical example of this was when I walked along Cloak Lane in the City a couple of weeks ago. Although I have walked through the street numerous times over the years, I had not noticed this foundation stone on a building on the corner of Cloak Lane and College Hill:

What caught my attention with this foundation stone is that it was laid by a Deputy Chairman of the Police Committee.

The building does not seem to have any current connection with the Police service and is now an office block, and appears to be on sale for offers in excess of £14.7 million.

The building looks as if it was once home to an institution of some form. Plainly decorated and mainly brick with stone cladding on the ground floor, the building still projects a strong, functional image onto Cloak Lane.

The foundation stone on the building is now the only reminder that this was built for the City of London Police and opened as Cloak Lane Police Station:

As the foundation stone records, Cloak Lane Police Station dates from 1885.

At the time, Cloak Lane was one of six police divisions across the City. They were centered on police stations at Cloak Lane, Minories, Bishopsgate, Bridewell Place, Snow Hill and Moor Lane.

The City of London Police came into being in 1839 when the City of London Police Act was passed on the 17th of August 1839. Before this act, policing in the City was built around a Day Patrol of Constables, and a Night Patrol which started with elected Ward Constables and Watchmen, with Watch Houses that later became the first Police Stations located across the City.

The 1839 Act provided statutory approval of the City of London Police, appointed a Commissioner of Police who was selected by the City’s Court of Common Council, and probably of more importance to the City of London, the Act ensured that the City’s police would be kept separate and not merged with the Metropolitan Police. A separation which continues to this day.

The City of London Police seems to have been funded by the Corporation of London, and funded by a police rate paid by the businesses and residents of the City.

There appears to have been some concern about the extra costs of the new building as in the City Press in 1885 there was the following: “There is every probability of an increase in the city rating, which is already exceedingly heavy. A new police-station is about to be erected in Cloak Lane which will involve an additional penny in the police rate, unless the cost of the building is spread over several years”.

I cannot find the exact date when the new station opened, however it appears to have been built quickly as by 1886 newspapers were starting to carry reports about events involving the station, including what must have been a most unusual use for the new police station:

“AN ADDER CAUGHT IN A LONDON STREET. There is now to be seen at the Police Station, Cloak Lane, City, an adder, about 15 inches long, which was seen in Cannon Street a morning or two ago basking in the sun on the foot pavement, although large numbers of persons were passing to and fro at the time.

A constable’s attention was drawn to the strange sight, and he managed to get it into a box and take it to the station. It is conjectured that it must have been inadvertently conveyed to town in some bale or other package of goods. The creature, which is pronounced to be a fine specimen, has been visited by large numbers of persons.”

I could not find any record of what happened to the adder after its appearance at Cloak Lane police station.

Cloak Lane is to the south of Cannon Street, and runs a short distance west from Cannon Street Station.

The building did suffer bomb damage during the war (although it is not marked on the LCC Bomb Damage Maps). A high explosive bomb did penetrate the roof and caused considerable internal damage. There are a number of photos of the damage in the London Picture Archive, including the photo at this link.

As a result of this damage, there may have been some repairs and rebuilding of the structure, and it is hard to be sure how much of the building is the original 1886 station.

The longest axis of the building is on Cloak Street, with the shortest axis running down College Hill as the building is on the corner of these two streets.

What is strange is that the main entrance to the building is on Cloak Lane, and the building was known as Cloak Lane police station, however as can be seen to the left of the door in the following photo, it has an address of 1 College Hill:

The arms of the City of London can be seen in the pediment above the door. I am not sure who the figure on the keystone is meant to represent, however it could be Neptune / Old Father Thames, as Cloak Lane police station covered the area along the river not far to the south of the building.

I find it fascinating to use these fixed points in London as a reference to finding out about life in the City over the years, and Cloak Lane police station tells us much about crime in the City of London.

Financial crime seem to be a feature of many of those of who found themselves in Cloak Lane police station. Probably to be expected given the businesses within the City. Two examples:

In September 1952, Colin Vernon Ley was awaiting trial, charged with “while being a Director of Capital Investments Ltd. he unlawfully and fraudulently applied £3,000 belonging to that body to his own use”.

The report of his arrest reads as you would perhaps expect of an arrest in the 1950s:

“At 6.45 p.m. yesterday, said the Inspector, I was with Detective Sergeant Reginald Plumb in Bruton Street, Mayfair, when I saw the prisoner outside the Coach and Horses public house.

I said to him ‘You know who we are, and I hold a warrant for your arrest issued at the Mansion House today.

I cautioned him, and he said ‘I suppose I have to come with you now’. At Cloak Lane Police Station, the warrant was read to him, and he said ‘You were in a position to prove it, no doubt before you got the warrant’. I was present when he was charged and he made no reply.”

On the 10th of October 1959, papers were reporting on the arrest of a solicitor for one of the largest, in value, financial frauds. Friedrich Grunwald, described as a 35 year old Mayfair solicitor was arrested and charged under the Larceny Act with the fraudulent conversion of £3,250,000 entrusted to him by the State Building Society to secure mortgages on properties owned by 161 companies. His arrest was described that:

“At a nod from a colleague, a bowler-hatted Detective-Superintendent Francis Lee, head of the City Fraud Squad, intercepted him on the Embankment near Temple Underground Station and escorted him to a car which drove to Cloak Lane police station”

In January of the following year, Herbert Murray, secretary and managing director of the State Building Society was also arrested and taken to Cloak Lane and would later appear in court with Grunwald.

The problem with using old newspapers for research is that there are so many random interesting articles to be found on the same page. If you have ever wondered why and when the Guards at Buckingham Palace moved into the secure area behind the railings, then on the same page as the above article there was:

“PALACE GUARD TO RETREAT BEHIND RAILINGS – Sentries at Buckingham Palace are to retreat behind the railings. They are making their tactical withdrawal to prepared positions to avoid clashes with sight-seers.

It will stop fashion photographers posing scantily dressed models under the men’s noses. It will stop those pictures of kindly small boys tie sentries undone bootlaces. Too often the boys tied the laces of both boots together.”

The River Thames features in a number of events that involved Cloak Lane police station. These normally involved some form of tragedy, due to the nature of police work, and the dangers of the river, such as in April 1924:

“POLICEMAN VANISHES – BELIEVED TO HAVE BEEN BLOWN INTO THE THAMES. Police Constable Albert Condery is believed to have met with a tragic death by being blown into the Thames during a storm last night.

It is learned that Condery, who has been in the City Police Force for 20 years, left Cloak Lane Police Station last night to go on duty at Billingsgate Market. He was seen there by the sergeant, but later he was missed, and his helmet was found floating on the Thames near the market. The body has not been recovered.”

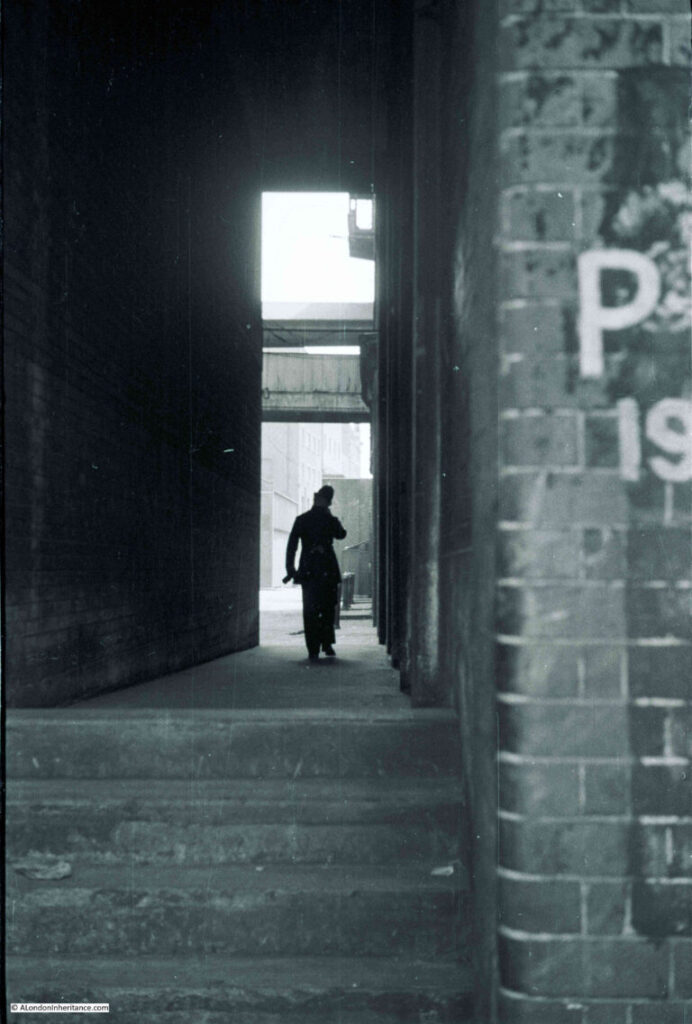

The above report was from a time when lone police officers patrolled the city’s streets. Although the following photo was taken by my father in Bankside, not the area covered by Cloak Lane, it does show the traditional image of a policeman patrolling their beat:

There were many strange events across the City in which Cloak Lane was involved. In November 1902, papers had the headline “EXTRAORDINARY AFFAIR AT BANK OF ENGLAND – ATTEMPT TO SHOOT THE SECRETARY. A sensation was caused in the Bank of England yesterday by the firing of a revolver by a young man who had entered the library. As he seemed about to continue his firing indiscriminately the officials overpowered and disarmed him. The police were called in, and he was removed to the Cloak Lane Police Station.”

He was unknown by anyone in the Bank of England and whilst at Cloak Lane, he was examined by a Doctor, who came up with the diagnosis that “the man’s mind had given way at the time”.

In August 1891, there were reports of a “Raid on a Cheapside Club”, which officers from Cloak Lane had been watching for some time, with a couple of Detectives having infiltrated the club. Finally there was a raid, when: “A party of 14 plain-clothes officers made a descent upon the premises. At first, admission was refused, and the officers proceeded to smash the glass paneling in the upper portion of the door. Resistance being of course in vain, the door was thrown open, and the detectives rushing in, arrested everyone found in the establishment. twelve persons were taken into custody, and removed to Cloak Lane Police Station.”

The report does not mention why the club was illegal, however reports in later papers when those arrested were in court reveal that it was an illegal betting club, known locally as the United Exchange Club, held in the basement in Cheapside that had been home to the City Billiard Club.

Another view of the old Cloak Lane Police Station. College Hill is the street leading down at the left of the photo. Cloak Lane is where the longest length of the building can be seen, but strangely the address on the main entrance is 1 College Hill:

In 1914, two of the original six divisions were closed, and the City of London police force was reorganised into four Divisions. These were changed from numbered divisions 1 to 6 to lettered divisions A to D, with Cloak Lane becoming D Division.

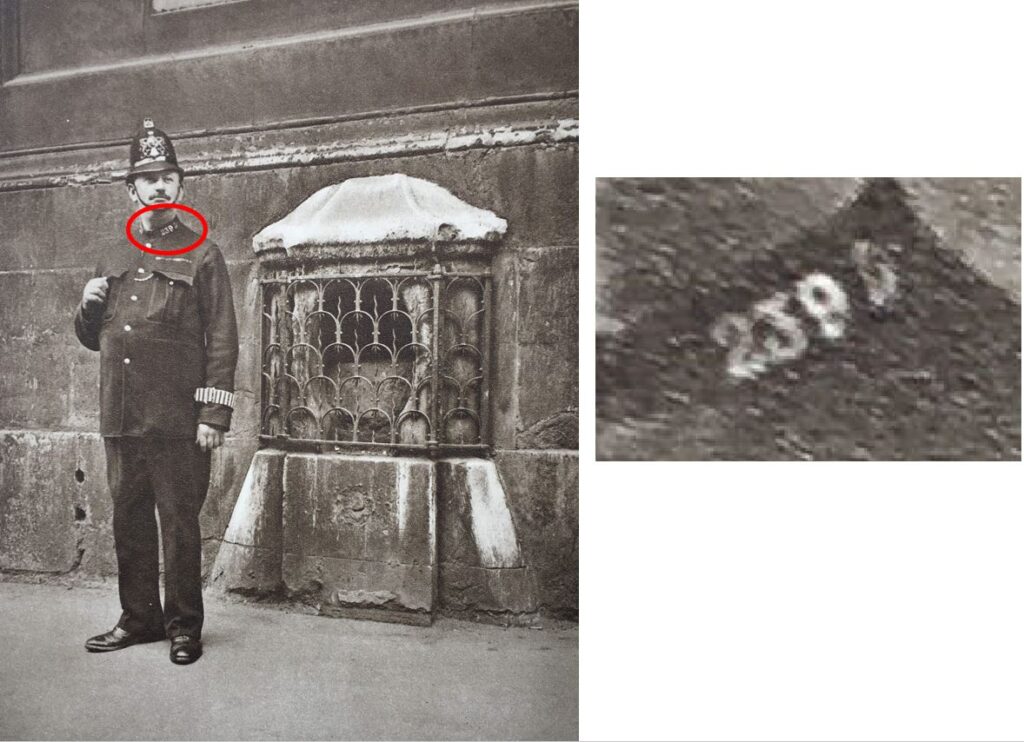

In last week’s post on the London Stone, I included a photo from the 1920s publication Wonderful London where a policeman was standing guard over the London Stone.

City of London police had their individual number, followed by a letter for their division on their collar, and looking at the collar number of the policeman shows he was from D Division based at Cloak Lane, which makes sense as Cloak Lane covered Cannon Street.

Cloak Lane Police Station survived until 1965, when it closed and Wood Street became the D Division police station.

The very last report mentioning Cloak Lane Police Station was from December 1965 when an article titled “Foolish Driver in The City” reported on a driver who was seen driving down Friday Street and only just stopping at the junction with Cannon Street. He was arrested on suspicion of being drunk and taken to Cloak Lane Police Station, where he “had to be supported by two officers because he was unsteady on his feet”.

And so ended 80 years of policing from Cloak Lane.

Wood Street (designed by McMorran and Whitby, and built between 1963 and 1966), and which took over from Cloak Lane is shown in the photo below:

Wood Street Police Station has in turn been closed.

In the announcement from the Corporation of the City of London, it is stated: “The Grade II* Listed building has been sold to Wood Street Hotel Ltd (wholly owned by Magnificent Hotels) after it was declared surplus to operational requirements by the City of London Police. The developers have purchased the property on a 151-year lease and will turn it into a boutique 5-star hotel, subject to planning permission.”

The architects plans for the building can be seen at this link.

The only indication that the building on the corner of Cloak Lane and College Hill was a police station is the foundation stone laid by the deputy chairman of the police committee.

It now has a very difference use, and those who enter the building are now presumably doing so voluntarily, unlike very many of those who entered the building between 1886 and 1965.

It now has a very difference use, and those who enter the building are now presumably doing so voluntarily, unlike very many of those who entered the building between 1886 and 1965.

Wood St nick above. I remember paying a visit there circa 1982 with others from our firm over parking in Trinity Sq (when it was possible in those days). I was free to go! From memory one or two brokers were putting (old school round) coke can rings into the meters instead of the correct coinage 🙂

Wood Street Station used to house an interesting, but small, Police Museum. I visited there many years ago whilst researching my family tree as a GGGfather was in the force. Does anyone know what happened to the museum when the station closed?

Allegedly within the Premier Inn hotel that will replace the now closed Snow Hill station, there will be a museum and hopefully the Wood St artefacts are in storage somewhere awaiting their re-emergence?

I wondered if the address was always 1 College Hill when it was a police station, or if giving it a new address on the side street was (with associated engraving by the entrance) was part of its transition to civilian use. Does the address in the stonework appear in any photos taken in police use?

A very interesting article as ever – My father PC 209E Basil Barnett joined the City Police in 1937 and, including war service in the Royal Marines, served as a PC until his 30 years were up in 1967. So the E Divisional suffix was still used although it looks like there were only 4 Divisions by then. Initially he was based at Cloak Lane, then Snow Hill, which was recently also closed permanently, and then Bishopsgate., which while is presently allegedly open ’24 hours a day’, in fact the front door is firmly closed in the evening and help is only available via a phone service.

To be fair this is not entirely surprising as pre-covid the population of the square mile was less than 10,000, an so, while over a million workers poured in during the day, the city was empty at night and at the weekends. Most of the ‘crime’ was business or financially related, with very little of the normal policing duties associated with road traffic, breaking and entering or street crime etc. Now, with the advent of the computer, financial transactions are all on line, so many of those back office staff are surplus to requirements and fraud is much more difficult- plus, with post-covid working from home, commuter numbers have fallen dramatically

Nowadays, on Mondays and Fridays the City is virtually empty and consequently far less police numbers are required and with so many fewer businesses requiring space, presumably the rateable income for the City Corporation has too fallen dramatically and so there is less income to pay for police numbers and ancillary supporting equipment and buildings? How times change!

Fascinating as always

Another brilliant read, thanks

Another fascinating article. The item about Buckingham Palace made me think back and I can remember as a young boy seeing the sentry boxes outside the palace railings. Living at the other end of Buckingham Palace Road, my parents would often take my sister and me to St James’s Park to feed the ducks on a Sunday afternoon in the mid 1950s. I can also recall how quiet it would be compared to today!

Francis

Great article thanks.

“Detective Sergeant Reginald Plumb” – I thought I was reading a Cluedo solution: Detective Plumb in the Police Station with the Fraud Squad. 😉

Re. the guards at Buckingham Palace, I always recall my father saying they were moved inside following an incident where a guard, fed up with the antics of a female tourist, decided it was time for his patrol and smartly brought his knee up into her groin!

Well done for your years of hard work and attention to detail. From an ex Londoner born in Hackney, now living in the Channel Islands, I do much look forward to your posts to enable me to reminisce. Keep it up kind Sir. Regards, Ex licensee of Jack Straws Castle, Hampstead 1983/7

Another interesting article – thanks.

I think the case of the shooting of the Secretary of the Bank England may have been of Kenneth Grahame (who then retired and wrote The Wind In the Willows). According to the Bank of England Museum, that happened in November 1903.

Alan Simkins – there’s a City of London Police Museum in the Guildhall complex, which includes their Olympic gold medal (they are still reigning champions in that event, as the tug of war is longer held for some reason). Could it be the same collection?

Interesting that one of the stations was at Bridewell Place. Explains the origin of the slang ‘Bridewell Taxi’ to mean Police Car.

The adder. Its arrival at the Police Station would very probably have been recorded in the OB

(Occurrence Book), which was (as I have seen brought into court in modern times) a large leather bound volume, with blank pages for the recording of all the matters brought to the attention of the constables at the desk, from lost dogs to Royal visits ( the latter evidenced by a Royal signature).

It would be v interesting to know what happened to such volumes once the pages were all filled up — & indeed whether such volumes were kept in some repository after modernisation of the recording systems.

Bombed 8th March 1941, when the most famous ‘incident’ was the Cafe de Paris bomb. Four people died here, three policemen and one civilian. A fifth civilian died at St Barts Hospital but had the police station as her home address – I think policemen could live ‘above the shop’ with their families at that time, but would welcome confirmation.

PC Frank Collins, age 34 – photo and biography here: https://www.natwestgroupremembers.com/our-fallen/our-fallen-ww2/c/frank-collins.html

PC William James Fairweather Dunnett, age 28

PC Albert George Ridley, age 46

Ronald Charles Adams, age 18

Pamela Winifred Hayward, age 15

Another splendid post. Interesting that the policeman pictured by the London Stone later had a career as the drummer in “The Beatles”, a rock group.

Lovely snippet of history. There are so many closed police stations in the Metropolitan area now but i never knew that there was this one so close to where i used to work. Will take a closer look soon.

I have been a devoted reader of your blog for some while now. It is truly inspirational. But in this particular blog, you touched on something which is absolutely fundamental to achieving historical perspective, but which is very very rarely mentioned, ie ways of reading urban landscapes. One day, I would love to have a one to one discussion with you re this. But how do I do it? I live in Oxford, am temporarily on the other side of London looking after someone recovering from major surgery. Maybe eMail. Maybe what’s app, or even better when I return to Oxford, you can come and test your skills there and do one of your away day blogs cf the recent Peterborough one. But did your father photograph Oxford? I can’t imagine he didn’t. He sounds as though he was a most resourceful chap, as are you for so faithfully following in his footsteps.

Regards, Malcolm Southan.

P.S. if I never hear back from you, no hard feelings. Just so grateful for your inspiring blog

My father Harold Robert Stringer 118D was based at Cloak Lane Police Station. His great friend Ridley was killed in that air raid. After his retirement in 1947 my Father and Mother remained in contact with Mrs Ridley. We lived in one of the Flats behind Bishopsgate Police Station and my father retired in 1947 after 27 years service. He died in 1980 and my mother passed on in 1986

Hello Harold

Your story made me think of my dad, PC Jim ‘Jakey’ Barnett who joined the CLP in 1937 and after war service was demobbed back into a different uniform in 1946 and was stationed at snow hill and Bishopsgate.

I was born in 1947 and we lived in Ferndale Court Brixton until 1962 and then in a police house in New Cross., My Dads 30 years service ended in 1967 but he carried on as a civilian prison van driver for several years after.

They moved to Eltham, Bexley and finally to Whitstable in Kent. My mum, Win, who worked in the police canteen during the war, passed away in 1989 and my Dad in 1992.

As the book says ‘the past is a foreign country- they do things differently there’ and quite what they would have made of todays world is one for another day.

Best

Peter